Each year, the grandchildren and their parents come to our home in Massachusetts for Christmas. We are in the central part of the state, north of Springfield, so we live in an area of farmland.

I have heard U.S.-born people describe their first trip to Africa with the word “stink.” You have to remember, Africa is not the zoo. These animals are the indigenous animals. So if you are downwind, you will get a strong scent. The reason I’m saying this is for people to understand that we live in the dairy-farm part of Massachusetts. Many cows. And on a given summer day, with some four hundred cows, you will get a whiff of whatever those cows happen to be doing. Welcome to non-Africa, USA.

To get to our home, one comes off the interstate, and then there are fourteen miles of inland driving. Roads that have been smoothed out by wagons, cars, flat-footed elk, and heavy-pawed mountain lions. Trails of things that either travel in herds or packs or all those groups that animals and birds and fish travel in. Like a school of rabbits.

No, no, that’s fish.

And over the years there have been a gaggle of geese, a herd of cattle, and a pride of pigs—no, no, that’s lions.

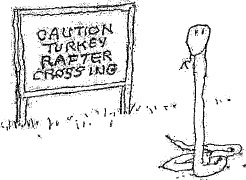

But anyway, the road has been flattened out, not so much by man, but by wheels and paws. I suspect there has even been a thing of turkeys along these roads. What do you call a thing of turkeys? A flock? No, that makes no sense because flocks fly. Yes, flocks fly far. And I have seen few turkeys flying either near or far. So I looked it up and found out a thing of turkeys is called a rafter. A rafter of turkeys. And the very day that I was writing this piece, I said to my grandchild:

“A thing of turkeys is not a flock; it’s called a rafter. A rafter of turkeys.”

And this seven-year-old female just kept walking and muttering something like: “Grandpoppy has lost it again.”

Then she went to my wife, who is Grandma, and said to her, “Grandpoppy is making up things again.”

My wife, who is the wordsmith of the house, without even being asked, came to me to find out why the grandchild had said “Grandpoppy is making things up again.”

Don’t ever make a mistake when you are using words with my wife. It’s better just to draw pictures. Because if you say anything to my wife, she will seek first of all to find out if you are using a real word or if it is not a real word. Then you can pronounce it two or three different ways, after which she will leave the dinner table and dig around to find out everything there is to know about that word.

So when I, through research, learned that a thing of turkeys is actually called a rafter, and then the grandchild went to my wife and said, “Grandpoppy is making things up again,” my wife came to me and said, “What are you teaching the children?”

Well, I could’ve seized the moment and attacked her by saying, “That is plural.”

And then she would say, “What is plural?”

My response would be: “You said ‘children.’ There’s only one child that I’ve spoken to.”

And then she would say one word: “Look!”

And that wipes out everything I have ever done or said in my life.

She had asked me, “What are you teaching the children?” So I answered. “A thing of turkeys is called a rafter.”

She immediately turned around and left the room. After a few minutes, she came back, and then she made a sound that I have only heard in movies when Native Americans are getting ready to speak English.

She said, “Hmmm.”

And I knew I was correct. Whenever I hear “hmmm,” I know I must be right.

Then she said, “Well it, doesn’t sound correct.”

Obviously, she was making up for the child saying I had lost it. Then she said, “You’ve got the reputation of being a mountain of misinformation.”

And I said, “Well, is that the same as traveling with a rafter of turkeys?”

“Yes,” she said. “When you are with your friends. That’s what it is. A rafter of turkeys.”

I could have come at her with a few more birds I found. Like a murmuration of starlings. A parliament of owls. A sedge of cranes. An exaltation of larks. Or even a convocation of eagles. And I could have switched to animals. A gang of elk. A clowder of cats. A leap of leopards. A shrewdness of apes. A mute of hounds. Yes, I could’ve done that.

But I thought better of it.

Anyway, it’s Christmas Eve and we’re at the house with the grandchildren. We have, at the time of this writing, three grandchildren: two sevens and a five. The boy is five and, as you know from reading this book, he is obsessed with Godzilla. And he hums. I don’t know if it’s the theme song from Godzilla, but whatever it is, he walks around humming.

To protect the grandchildren, I will not give you the correct names. That’s because, as of this writing, my wife has not agreed that it’s all right to use the grandchildren’s names. So I will do something I have often done in my past. I will give these people nicknames. And these nicknames may not have anything to do with the names given to them at birth. To me a nickname can be because of what the person looks like or sounds like—in a Damon Runyonesque way.

Three grandchildren. The two girls are both seven. One shall be called Camille II, as in Camille Two or Camille the Second. The other one shall be called Lacey. And the five-and-nine-tenths-year-old boy shall be called G.P. Which is short for “growing pains.” These kids have an energy and my wife loves these people, but they have decibels. When my wife said they were coming for Christmas again this year, I didn’t say anything. That’s because I am a husband for forty-six years. You pick your battles. And I have a long list of things that I have passed up.

Now, I love my grandchildren, but everything with them is a matter of loud crying or loud laughing. We don’t know many of the quiet moments unless they’ve found something for themselves and nobody else is bothering them. The girls appear to do fine when they’re playing together and talking to dolls. But the boy is a loner. He walks around by himself making Godzilla noises.

However, it always seems that from the very room where the girls are playing nicely, I eventually hear a scream, which echoes all throughout the house:

G.P.! Stop it!

And then one of the girls will run out of the room crying, the decibels very high, crying and talking in a way that I can’t understand anything she is saying. That’s the problem with everybody who cries: You can’t understand what anybody did to cause the crying.

As they cry and talk, it’s almost as if they’re about to collapse, especially when they hit the emotional, shrieking, “this is the worst thing ever in my life” wall.

Then, at some point, the crying and talking turn into anger, which causes the slamming of a door. In my house, not in their house, when they slam these doors, the vibration goes around and hits some other doors in the house. So, if a door slams on the second floor, doors on the first floor react. Some doors just kind of move back and forth and bang against the doorstop. Others close on their own just because of the door slamming on the second floor. So what we have is a slamming by a seven-year-old that creates a vortex that causes other doors that are not locked to move in solidarity. Some opening, some closing. So we keep having to remind these people not to slam doors.

On this particular day, when I heard G.P.! Stop it!, all I wanted to do was catch the G.P.! Stop it! scream before it became crying and the slamming of the doors. I went in the room and I saw that G.P. was caught. He had something in his hand that belonged to one of the girls, and she was about to cry. And the girl, Lacey, was loud. You see, before the crying, first comes the loud.

“G.P. took that and it’s mine!”

She says this very, very loud.

G.P. comes to defend himself. He’s looking at me, his mouth open, and I guess he had a great deal of hope that I would side with him. And he said, in a very loud voice, “She wouldn’t let me play with this!”

I said, “Well, who does it belong to?”

He said something like, “I don’t know who… she won’t let me play with this!”

And he stayed with that, that it was her fault.

“I haven’t done anything,” G.P. insisted. “She won’t let me play with this!”

And Lacey kept saying, “It’s mine and you took it!”

And he said, “But you won’t let me play with this!”

That was his defense. Over and over. There he was holding something that belongs to someone else and his defense consisted of: Okay, it’s hers and I have it. But she won’t let me play with it!

Just so you understand the brain of a five-year-old, let me explain this young man’s ability to reason. I was sitting in that same room—it was not Christmas, it was not Easter, no holiday—the children had come for the summer to visit. G.P. and Lacey were there playing. And he was playing by himself, pretending to be a train conductor on his own train. Lacey noticed this and said, “G.P., I need you to be the conductor for my train.”

He said he would do that. Three minutes later, she said, “G.P., I now need you to start as the conductor of my train.”

And he said to her, “I’m sorry to tell you this, Lacey. But I won’t be able to be your conductor.”

He was just being nasty, and I knew that.

So Lacey said, “Then you’re fired!”

G.P. dropped everything he was holding and turned into a crying, screaming child.

“She’s being mean to me, Grandpoppy!”

I said, “Wait, wait, stop! I heard you say that you were sorry you couldn’t be the conductor.”

G.P. started crying and talking.

“Buk shir divint plash ma!”

“Look, G.P,” I said, “you had already quit. Why are you crying because she fired you?”

And he just kept crying and talking at the same time. He never even said “She can’t fire me.” I just think he was upset because she, in a way, topped him.

Now, on this particular Christmas Eve, I received a call from one of Santa’s helpers by the last name of Jones, who asked to speak with my grandchildren. I did not know, nor did I ask, how assistant Jones got my phone number. So I said, “Just a minute,” and I gathered the children.

“An assistant of Santa Claus is on the phone. Her name is Miss Jones and she wants to talk to the three of you.”

And they all did everything the same way at the same time. They walked into the room as if they were fused at the shoulders, all in the same position. Their heads dropped to look at the phone in the same way at the same time. I put the call on the speakerphone, which was on a leather chair, as it has always been. And they stared at the red light that said “speaker.”

“Miss Jones,” I said, “the children are all here.”

“Hello,” Miss Jones said.

Camille II, at age seven, was close to becoming an agnostic when it came to Santa Claus. But when she heard the voice of Miss Jones, her expression transformed to one I can only imagine an agnostic would have during a surprise visit from God.

And the expressions on the faces of the other two changed as well. There was a look in their eyes—their eyes all of a sudden appeared to look clearer. Their faces, when I said Santa Claus, an assistant of Santa Claus, they seemed to brighten. It wasn’t a smile, it wasn’t an expression of cheer; it was just a look as if they had been blessed. All of a sudden, I felt an aura coming from the three of them. Not that I could hear a thousand monks humming something Latin in unison, but it was obvious that they had gone into some sort of reverent zone. They just stood there in silence, saying nothing, their mouths slightly parted. And they blinked—it wasn’t a fast blink or a slow one. Just a blink. These children were in a trance. It was like the people doing tai chi in Chinatown when they stared at the tree and held the position. Then the children’s heads turned down to look at the phone. And they never even registered that I was there.

Miss Jones asked, “Is Lacey there?”

And Lacey answered in a Gregorian tone, “Yeeeesss.”

Miss Jones, Santa’s assistant, said, “I have your list and I just want to go over it with you.”

Lacey did not breathe. She just, with her mouth partially open, kept looking at the red light on the phone that said “speaker.”

As Miss Jones went over the list, the child Gregorian-ed:

“Yeeeesss.”

“Yeeeesss.”

“Yeeeesss.”

And then she went to the second grandchild.

“Who is Camille Two?”

And Camille II also answered in this Gregorian chant–like voice, “I… aaaaam… Caaaamille… Twoooo…”

Then Miss Jones said, “Good. I’m going over your list. Are these the things you asked for?”

“Yeeeesss.”

“Yeeeesss.”

“Yeeeesss.”

When Miss Jones finished with the two girls, she said, “G.P.”

And G.P., who is five, tilted his head toward the ceiling, and he said, “I have been naughty. But as of the last three days I have been very nice.”

And I thought, this is just wonderful. Here is this five-year-old boy cleaning up his act. Confessional lying. The boy will admit to a few bad things because he believes Santa knows everything but then comes back with a few good things from the last couple of days.

“The good one is here in Massachusetts.”

“Yes,” Miss Jones said. “I’m looking at film of your behavior over the last six months, and you have made some errors. But lately you have been stellar.”

“What is that?”

“Stellar means better than good.”

“Yeeeesss,” G.P. said. “The last three nights I have been very nice to… to… to… to everyone.” And then he said, “And God bless you!”

“Well, thank you,” Miss Jones said. “I’ll get this to Santa. And before I go, please be aware that you may get a call from Skyler, Santa’s navigator.”

Upon hearing that, the children went back to those trancelike expressions again.

I said, “Good night, Miss Jones.”

“Nice talking to you, Mr. Cosby. I have all of your records.”

“Thank you.”

“And Santa wants to know when you’re going to make a record about him.”

“Soon. And I’ll be nice.”

“It’s too late for you, buddy,” Miss Jones said as she hung up.

The children walked out, still joined at the shoulder, as if they had been practicing these walks. I don’t know if it was my imagination, but I swear I could hear Gregorian chants coming from the other room.

As Miss Jones had said, I then got a call from a person named Skyler, who said he had to speak to the children because he is routing Santa’s travel with the reindeer. So I called the children and they came back in, shoulder to shoulder. Again, maybe I was imagining it, but it looked like somebody had put a bowl on G.P.’s head and cut his hair in the style of a Franciscan monk. And they all went right back to those same Gregorian expressions again as they then dropped their heads and stared at the red light on the speakerphone.

“Mr. Skyler,” I said. “The children are here.”

“Very good. What are your names?”

And they never moved their heads when they answered.

“Lacey.”

“Camille Two.”

“G.P.”

“I just want to know,” Skyler said, “because I’m the fellow who guides Santa and the sled and all the presents and the reindeer, and we want to know exactly where your house is. Where are you?”

They said, in Gregorian unison, “We’re in Massachusetts.”

“Where is it in Massachusetts?” Skyler asked. “We don’t understand where you are because there aren’t any children living there, just people who can take care of themselves. Grandparents and aunties and uncles. They buy their own things. And they are generally awake when Santa gets there. So they want to talk, ask how Santa’s wife is doing and have a long conversation. But Santa is channeled, he’s working, and he just doesn’t have that much time because he is very, very busy. He doesn’t have time for chitchat. He’s working and he doesn’t want to be late. So, if there are no children, Santa crosses that house off his list. But because you are visiting Grandpoppy and Grandmommy, I need one of you children to tell me how to get to your house.”

“You get off the plane,” Camille II began, “and then you ride a long time.”

“How long?”

“You fall asleep.”

“Okay,” Skyler said.

“And then,” Camille II continued, “you wake up and you come to, you know, the circle. Be careful. If you miss the circle you’ll go to Vermont.”

She kept saying “you know,” as if Skyler should know these landmarks in Massachusetts. And she started naming places on the way from the airport to the house. All the places she wanted to eat.

“And you go past, you know, Friendly’s restaurant, and, you know, Taco Bell, and then you keep going, and after that… there’s nothing after that.”

“I don’t know these places,” Skyler said. “Which interstate is it?”

“It’s the one in Massachusetts,” Lacey said.

“Yes, but what is the number of the interstate?”

“It keeps changing,” Camille II replied.

“What do you mean?”

“It used to be called 29.”

“Is that the miles?”

Camille II was very quiet because she wasn’t sure what to say. Finally, she said, in a very small voice, “Yeah.”

“You go down past two farms,” Camille II explained. “One with horses and one cows. That’s our next-door neighbor. They have a lot of black cows. But when it’s nighttime you can’t really see them. You have to do a curve and then straight. And you’ll see our house with the gate in front. You can tell it’s Grandymommy and Grandpoppy’s place because they have nothing. No cows. Just little children.”

Skyler got the directions, but he was still rather confused about where the house was, so he asked them if they, right then, would go outside because he had a special television screen that could see all over the world. If they went outside and looked north, Skyler told them, he would be able to see them and then he could show Santa how to get there.

I went and got their parents. And their parents were smiling.

“You’ve got to hurry,” Skyler said over the speakerphone, “because Santa is just about ready to take off. And I just want the children out there. No parents. And they have to look north.”

So they all went out and their parents were yelling from inside, “Look north! Look north!”

And the three of them looked in three different directions.

“Tell them to point to the house,” Skyler said.

“Point to the house!” their parents shouted from the doorway.

And they did. I could see they were really cold, but they didn’t mind.

“I saw you,” Skyler said when they came back in. “Now I have to go and explain to Santa where you live.”

Just as they were leaving the room, shoulders fused, a third call came in. It was Santa’s dietician. And his name was Stymie.

The grandchildren stood, focused, tai chi expression on their faces again, the most well-behaved people. And the Gregorian aura was back around them.

I put Stymie on the speakerphone and the children are standing there and staring at the red light and Stymie tells them that Santa, due to dietary restrictions, cannot have cookies and milk. And I never really thought about it, but by the time Santa gets to our house, he has eaten five thousand cookies and nine hundred pieces of cake. Which is probably why he hired a dietician. After years of eating all the things children have left out for him, Santa probably had a bad checkup and the doctor told him he had to watch what he ate.

“Please do not put cookies and milk down there,” Stymie instructed the children.

So Lacey said, “I already made chocolate chip cookies for him.”

“Santa cannot have them,” Stymie insisted.

So I barged in and told Stymie, “You go ahead and eat them and drink the milk.”

“How about Silk?” Camille II asked. “Soy milk.”

“Santa doesn’t like soy,” Stymie replied. “He just wants a glass of water.”

G.P. asked, “Bottled or the well?”

And Stymie said, “From the glass bottle.”

And G.P. (remember, he’s only five) said, “Okay, I will leave a glass bottle of water and an opener because you have to have a bottle opener for it. But leave the opener, don’t take it, because a lot of people keep taking our openers.”

“Okay,” Stymie said, “you guys take it easy. Bye-bye.”

The children left the room, fused at the shoulders once again. And quiet.

“I have never seen such good behavior,” I said to Stymie.

And then the disembodied voice of Santa’s dietician boomed over the speakerphone:

“Yeah, they should do this stuff every three months.”