Contemporary art is a cuttlefish, I thought, looking down at the video monitor on the table. It glides through the ocean of the present, tentacles waving, taking on the color of everything it passes. On the screen, animated figures ran back and forth against a jungle backdrop. The image had the washed-out, runny look of an old VHS tape copied and recopied, then digitized and compressed. I made a note: be sure to mention this washed-out, runny look.

Or, it’s a vast, continent-spanning fungus: on the surface it seems like a million different organisms, but underground it’s all one big mushroom. The crit space was filled with an impressive amount of work that everyone was trying not to bump into as they milled around, clutching paper cups of coffee and dragging folding chairs. A person-size linoleum obelisk rested on a kidney-shaped swatch of Astroturf. A pedestal displayed the base of a piece of kitsch ceramic statuary, now absent its shepherdess or sad clown. A wood-paneled partition created an alcove in one corner of the room, lined with red shag carpet and decorated with collages and drawings. The four monitors on the table broadcast loops of footage (the telecast of a professional football game, some home movies, the cartoon I was now staring at), creating a dense, lurching noise. The overall effect of the installation was of a suburban rec room that had been dismantled, its contents itemized, placed in boxes, and shipped to Providence, Rhode Island, and then carefully reassembled by people who had no idea what a suburban rec room was. By aliens perhaps. (I wrote down “aliens.”)

What was the mythological creature with the head of a lion, the body of a horse, et cetera? Ah ha. Contemporary art is a chimera. It has the head of pop culture, the torso of critical theory, and the loins of finance capitalism. Was this a better or worse analogy than the cuttlefish, the fungus? I was floundering. The cartoon figures rushing maniacally around on the screen resolved into professional wrestlers from the 1980s. I recognized Hulk Hogan, Captain Lou Albano, and one other, tantalizingly familiar . . .

People were now vying to position their chairs on the side of the room opposite the table with the TVs on it. “Can you turn the sound down?” somebody asked. Doug, the artist whose work we were contemplating, leaned over and fiddled with some knobs. The noise subsided to a low hum.

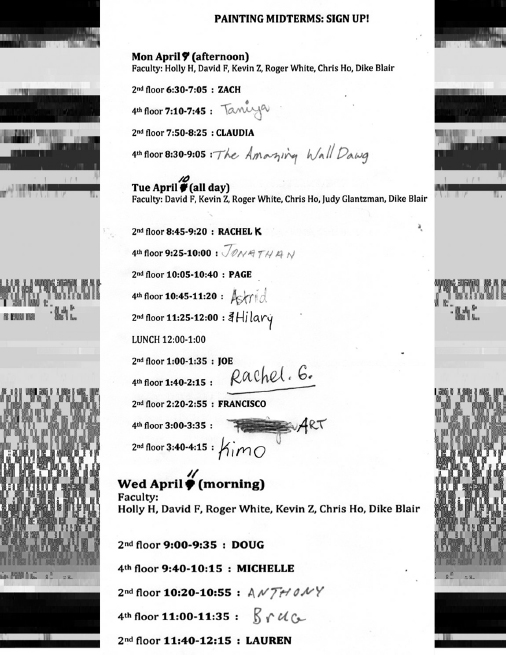

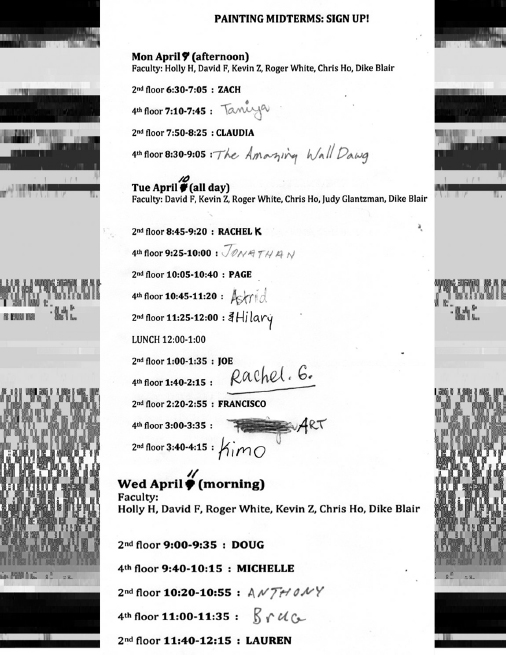

This was Wednesday morning, the third and final day of the spring 2012 midterm reviews at the Rhode Island School of Design, Department of Painting, Master of Fine Arts program. I was there to offer feedback to the students in my capacity as a critic for the department. We (nine faculty in all, including myself, and nineteen students) had been critiquing art more-or-less nonstop since Monday evening.

We had seen and discussed many things: tie-dyed bedsheets, a chair made out of concrete, a copy of a Picasso painting, a photograph of spackling paste. My concept of painting, not to mention art, was starting to fuzz out around the edges. Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka—that was the name of the wrestler. There were five more critiques to get through today.

The midterms at RISD last thirty-five minutes each, with five-minute breaks in between and an hour for lunch. To keep to this schedule, the reviews alternate between two critique rooms in the studio building, one on the second floor and one on the fourth. A complex choreography takes place between the sessions. While the rest of the group migrates from one room to the other, the student whose review has just ended and the student whose review will happen forty minutes later stay behind, to help each other take down and hang their respective artworks. Both then rejoin the session under way, like performers returning to the stage in the middle of the next scene. In theory, this allows a fluid process of nonstop art criticism with minimal downtime. With so much art to talk about in so little time, even short interruptions or overages can snowball into extensive delays, with cascading disruptions to professional and private life: canceled classes, missed trains, unpainted paintings.

Each art school is a world unto itself, with its own deeply ingrained manners and quirks, but I’ve done three semester’s worth of midterm reviews at RISD now, and I’ve begun to get a handle on the dynamics of the situation here. In the entire two-year MFA program, these are the only occasions in which the entire program is gathered in one place for a public discussion of a student’s work, and a sense of ceremony accompanies each one. The midterms create a seasonal narrative. In the fall they tend to be harsher, and in the spring they’re gentler. In the fall, students are stripped down in preparation for a cold winter of artistic self-doubt and desolation, and in the spring they’re renewed, cultivated, and psychically reconstructed. The reviews are operatic: they reach soaring heights and plummeting depths of emotion, with booming ensembles and sustained arias of enthusiasm or doubt, approval or invective. Like operas, they can also be tedious, and they’re grueling for everyone involved. Page Whitmore, a second-year student, told me that the experience is “like getting the shit kicked out of you in the most loving and respectful way.”

From kindergarten through college, an art class means a room of people making art together: you flail with the crayons, paint, or clay, performing a traditionally private activity in full view of the group. At the graduate level, actual art-making happens off-hours, outside the classroom. Here, an art class means conversation; the flailing is exclusively verbal.

On Monday evening, for the first session of this spring’s reviews, we’d walked into a room full of sculptures, not paintings. This was less surprising than it sounds. RISD organizes its graduate programs into separate, medium-specific fiefdoms (painting, sculpture, photography, digital media, and so on), but not everyone here in Painting makes paintings. Painting is more like an organizing principle, or a coat of arms, than an actual thing that students are required to do. So Zach, an artist in his first year in the program, was leading off the midterms with a group of festive assemblages in cardboard, wood, and fabric, dripping with whorls and curlicues of brightly colored paint. They occupied the critique room like a clan of hippie street urchins. Perhaps as a concession, he had also tacked an unstretched canvas up on one wall.

Duane Slick, the director of graduate studies, called the group to order. Zach listed the titles of his sculptures, pointing to each: “This one is Party with Punchbowl, this one is History Painter, there’s Saskia, Prince—”

“Prin-TSS or Prin-SUH?” someone asked.

“Prin-SUH. Then there’s Trap, Valentine with Meatballs, Time Machine, Tree, Dead Mermaid . . .”

Someone asked for the chronology of the work, and Zach obligingly repeated the titles in order of completion: Dead Mermaid, Valentine, Time Machine . . . This ate up the first two minutes of Zach’s allotted thirty-five.

“The first word that comes to his mind is decorative,” said Chris Ho, another critic in the department, and a few seconds passed while we mulled this over. The group had by now fanned out along the perimeter of the room, and we were craning our necks to see one another between Zach’s sculptures. Decorative how? we wondered. Decorative as in merely, as in frilly, as in the opposite of serious? Or decorative as in smart and subversive—as in, Zach is embracing traditionally feminine practices hitherto marginalized by the discourse of advanced art? The word sat in the middle of conversational space like a thrown gauntlet.

Zach leaned on the doorframe, possibly contemplating a quick exit if the critique went further south on him, and didn’t say anything. He wore a rumpled black blazer over an untucked gray shirt with dark-rinse jeans and black boots. He had big round glasses and a flop of brown hair parted on the right. At thirty-four, with a four-year-old daughter, Zach was on the older end of the age spectrum in the program. Whereas many of his classmates came in straight from college, undergraduate art school, or part-time jobs, Zach had been working in the trenches of the art world for about a decade, running a nonprofit gallery in Binghamton, New York.

After he was invited to interview for candidacy to the program in the fall of 2010, his house burned down—on the day after Christmas, no less—while he and his daughter were out. Firefighters saved as much of Zach’s house and his stuff as they could.

A month later, he drove a van full of his surviving art to Providence for the RISD interview and stayed in a hotel. He went out to a bar and had a few drinks. He couldn’t remember where his hotel was and had to get a ride back there with the bartender, whose generosity of spirit made him feel that Providence was a fine place. He couldn’t find parking on College Hill near the Painting Department offices, so he walked to the interview with his art in a plastic bag. The bag ripped, drawings floated down the streets of Providence in the snow. He showed up late. Earlier that morning someone had accidentally leaned against an expensive painting by a visiting artist that was hanging in the gallery outside the interview room. It had made a dent and everyone was freaking out. The interview began. A professor wondered what Zach ideally saw himself doing in ten years. “I don’t know,” he answered. “Living?”

“I want to know if Zach knows what Chris means when he says, ‘The first word that comes to his mind is decorative,’” asked Holly Hughes, the chair of the department. Still nothing from Zach.

Chris clarified. “The objects are worked in a decorative way,” he said, “and the elements that stick out for me as incongruous are the objects that are unmanipulated by you.” One kitelike thing suspended from the ceiling with bungee cords had a tattered paperback copy of Dianetics strapped to it; another wore three or four electric bug zappers.

A professor named David Frazer voiced a preference for the single painting on display, a crudely painted room with a striped couch and a blobby pink humanoid in the foreground. The sculptures, in contrast, seemed aimless to him.

Zach was finally moved to a response. “I have a full concept of the shape and form of what these are going to be,” he said, a little huffily.

I left my chair and walked out among the sculptures. It’s good to have a strong opening line in group critiques, I’ve found, to let everyone know where you stand and that you’re going to be a central player in the debates to come. There’s a certain amount of verbal one-upmanship that happens when artists, who spend a lot of their time in small rooms by themselves, are suddenly put in a larger room with one another and told to have a conversation. All the day’s pent-up language comes out at high velocity.

I pointed out a detail of Zach’s art: at the base of several of his sculptures, he had placed small bowls with roundish lumps of painted clay in them. What could they mean? “They look like turds, or donut holes,” I said. Silence from the room.

Holly was still goading Zach, trying to get him to commit to a line of interpretation. She listed things that his work reminded her of: the reality TV show Hoarders and “people being buried alive by their own possessions,” the Burning Man festival, the choreographer Pina Bausch, German Expressionism—“you know, ‘let’s all get naked and play primal man.’”

“Are they hermaphroditic? Can they reproduce?” she asked. We surreptitiously inspected the sculptures for signs of male or female genitalia. Duane Slick called time.

Different MFA programs structure their group critiques in different ways, determined by each program’s idea about who should or shouldn’t be allowed to talk. In the Painting Department of Virginia Commonwealth University, students undergoing candidacy reviews at the end of their first year introduce their work but refrain from speaking during critiques after that. In Mary Kelly’s weekly three-hour critique class at UCLA, a former student told me, students under review maintained a strict silence until the end of the discussion. At Columbia, where I did my own MFA, everybody just talked over one another. I doubt that any of these protocols are ever written down; they seem to pass silently from year to year, slowly hardening into institutional habits.

At the start of each review at RISD, the student is given a few minutes to preface his or her work with a brief statement, and the rest of the critique is nominally open. In practice, the faculty talks for about 90 percent of the time. Even among us, it’s hard to get a word in edgewise. You either have to cut someone off or time your remark down to the millisecond.

Each of the faculty members has a signature style of critique, with distinctive verbal flourishes and motifs. They function like an ensemble cast. Holly Hughes, the chair, gruff, good-natured, with whorls of auburn hair pinned back in a bun. Chris Ho, a stylish and animated young critic. David Frazer, a senior professor, white-bearded and avuncular, affably combative. Kevin Zucker, an associate professor and the youngest full-time member of the faculty, thin and quick-witted, with chunky glasses.

Joining them onstage are Dike Blair, a soft-spoken senior critic, in charcoal shirt and dark jeans; and Duane Slick, the director of graduate studies, in black jacket and jeans, who reserves most of his commentary for pivotal moments in the critiques. Lastly, your narrator, distracted during this session of reviews by attempting to simultaneously talk and write everything down.

For her review, Astrid chose to invite the group to her studio rather than to install her work in either of the critique rooms; her large inkjet prints are difficult to move around without dinging up the corners. She makes most of her art on the computer, so her studio is generally tidy, but for the review, it was immaculate: everything but her work had been pushed to the far end of the room and wrapped in brown kraft paper. We sat on the floor.

Astrid’s work had to do with travel: pictures taken through the windows of a train showing a blurry landscapes, pictures taken through the windshield of a car as the windshield wipers swept across the glass. David Frazer pointed to several enlarged photographic close-ups of chunks of Spackle scraped against a wall with a putty knife. He preferred these to the car and train imagery, he said; the latter were based too much on taste. “Like someone who photographs a bunch of lovely doors in Puerto Rico and then arranges them by their palettes.”

Kevin Zucker disagreed. The spackle pictures reminded him too much of the games at the back of the Ranger Rick children’s magazine, in which the reader is presented with a cropped and magnified picture of a pebble or a ladybug wing and is instructed to guess what it is.

Before I went to graduate school, I thought that people there talked about art in crisp, gnomic propositions, laden with references to theory and art history. I’d imagined serious young artists trading glosses on Walter Benjamin, professors in black crepe jackets nodding sagely at sculptures and saying, Ah, so you see, Conrad, the significance of the form is contradicted by the form of the signification.

Later, I realized that that’s how people write about art. How they talk is looser and rougher: an improvisational word-cloud breathed out around objects and endowed with a temporary, contingent significance, like the nonsense syllables that seem momentously important in a dream but evaporate upon waking. The talk is groping, tentative, fluid, but not always graceful. This is as much a matter of style—a preference for the offhand over the polished—as it is a necessary result of the way critiques are conducted. People are responding in real time to something they haven’t seen before, and time is limited, so they tend to go with the first thing that pops into their head.

So here, for example, “Ranger Rick” became shorthand for the simple perceptual trickery that Astrid might be wise to avoid, and we batted the phrase around for a few minutes. Was the work too Ranger Rick? Is Ranger Rickness a valid agenda for art? What is the historical function of Ranger Rickitude? “Unless you’re really going to blow my mind, I don’t think it’s enough,” Kevin said.

“This may sound mean, but I mean it as the defense of a struggle,” said Holly, who was perched on a paper-wrapped desk or file cabinet near the back of the studio. We quietly waited for her to rip Astrid’s work to shreds.

She didn’t. The meaning of Astrid’s work, Holly said, is its inability to communicate the emotions of the artist regarding the subject matter it presents: the wan glances through car and train windows, the aching beauty of the irretrievable, infinitesimal moment between two passes of a wiper blade across a rain-streaked windshield. “You’re continually referring us to something you value, and the mechanism of the art part is banging around and clunking,” she said. We picked ourselves up and headed on to the next crit.

The critique room on the second floor is a double cube of about seven hundred square feet with generously high ceilings, bisected by a thick support column. You enter on the northeast corner of the room and face a wall of windows with dark green wainscoting and vertical plastic blinds, grubby around the edges with residual charcoal and paint; the other three walls are drywall pocked with a million thumbtack-diameter holes, painted in layer upon layer of matte white latex. The floor is an institutional light gray. On the ceiling are strips of fluorescent lights and tracks of movable halogen floods—the floods counterbalance the deadening effect of the fluorescents on the art. A metal duct runs down one concrete column on the northeast wall, joining a system of intake vents and ducts that runs through each studio on the floor, collecting solvent and paint fumes and then moving them along a central pipeway, up an airshaft, and eventually out of the building through an exhaust fan on the roof in one big neurotoxic cloud. The whole system makes a continuous low whooshing sound, so the reviews sound like they’re happening in the cabin of an airplane.

The critique room on the fourth floor is smaller, squarish. It’s on the western corner of the building and has two walls of windows with a narrow sill, on which it’s almost possible to balance during reviews. The room overlooks a parking lot. Students sit and smoke on raised planter beds on the sidewalk below. Across the street, you can see the dining hall of the Johnson and Wales business and hospitality school.

Down on the second floor, Zach’s sculptures had disappeared. The lights had been switched off, and the chairs were arranged in a neat semicircle facing the northeast wall. Twin projectors sitting on pedestals projected the cluttered desktops of two MacBook Pros. “Everyone, if you can turn off your cell phones,” Claudia said while ushering us to our seats. On the wall opposite the projections were two five-by-five-foot paintings lit by tungsten floodlights on stands: one was a white circle with gray polka dots, the other was a pink field with lighter pink stripes.

Claudia pressed a few keys on a laptop and one screen came to life, showing ominously rolling thunderclouds, a dramatic soundtrack of shrilling, synthetic chords, and then Claudia in a tight black top, skirt, and high heels, flanked by two female dancers. While the clouds rolled smoothly across the screen, the figures vamped for the camera in jerky stop-motion. The music crescendoed, a beat kicked in, and the other screen displayed a wall of flame lashing against a black ground, and then Claudia again, in extreme slow motion, wrestling with a man in a white wife-beater who was trying to pin her in an embrace. This went on for eight minutes, and then both videos ended abruptly, one a few seconds before the other.

David Frazer started the discussion with a barrage of questions: Was the ending meant to be so choppy? Was this a finished piece? Why were the paintings lit that way?

Claudia, who is from Chile and once impersonated Britney Spears on a reality TV show there, said that the paintings were derived from the backgrounds of album covers: the circle with polka dots was from Mi Reflejo by Christina Aguilera; the pink stripes came from a German mashup of Coldplay and Nicki Minaj. The lights were meant to suggest a photo shoot. Yes, the video piece was finished; yes, the ending was meant to be abrupt. “I wanted it to be very painful to look at.”

Kevin said, “I’m concerned about where the pain takes us.”

A guy with longish hair and glasses pushed up onto his forehead said he preferred the paintings over the videos: the paintings, because they were essentially props, had an “open-ended productive capacity” in which viewers could make their own images. The video provided only “a somewhat predictable roughness masked as critique.” He turned out to be a professor in the Digital Media Department, and he disappeared after Claudia’s review.

We discussed production values: Were the videos meant to seem amateurish? If Claudia had had an unlimited budget, would the work look the way it does? Claudia said she wanted to make art the way a fan does.

Chris Ho proposed that the fan, as per Claudia’s description of her process, “is not the expert, and also not a mere passive enjoyer” of art or music; instead, “the mediocrity of the fan proposes a new subject position for art-making.” Someone mentioned Lil’ Kim as we filed out of the room.

On the fourth floor, in the last review of the evening, a long wooden box hung from a pulley system screwed into the ceiling. It was about six feet long, open on top, lined with plastic, and full of water. A set of metal rails ran down its length.

I had no idea what it was supposed to be. I worried that I’d suddenly lost the ability to understand contemporary art, and I suspected that this feeling was similar to the proverbial dream of the actor forgetting his lines. It was getting late. I glanced around the room; the other faculty, more accustomed to the marathon lengths of these things, seemed to be doing fine.

The artist, Wally, saved me by walking up and introducing himself. He had short dark hair, a faded T-shirt with a picture of an Indian chief on it, teal jeans, and Birkenstocks. He showed us a video of an impressive project from last semester: a huge, glass-bottomed pool mounted above the heads of viewers in a gallery, into which twinkling droplets of water fell from lengths of monofilament.

Then he addressed the big box. He placed a white panel on top of the metal rails, squirted some black acrylic paint out of a squeeze bottle onto it, kicked aside a set of blocks and grasped two of the rope ends dangling from the pulleys. The box started to rock back and forth on a central fulcrum, sloshing the water inside from one end to the other. The panel slid on the rails, causing the puddle of paint to move slowly across its surface. Eureka—the box was a wave-powered painting-making device.

Wally strained at the ropes, leaning backward and then easing up, to get the big box moving of its own accord. “It’s like you’re sailing,” someone observed. The blob of paint undulated on the panel, but it didn’t seem to be producing quite the interesting abstract pattern Wally was aiming for. After a couple of modifications to the setup, he eased the box down on its supports and dropped the ropes.

David Frazer said he found it interesting that the machine was so elaborate, yet it seemed to do so little.

“What if it did nothing?” asked Kevin Zucker.

“It’s already doing nothing,” grumbled Wally.

Holly Hughes cited the work of George Rickey, a kinetic sculptor.

Wally said that the piece we were looking at, titled Water Table, was a sketch; what he’d really like to do is make a forty-foot-long wave machine. A second-year student named Bruce said he’d enjoy just watching a forty-foot wave travel back and forth; for him, having the device make a painting was superfluous.

“But then it’s just, like, a large stoner toy—one of those lamps,” said Art, another second-year student. Conversation looped back to the symbolic dimension of the piece: was this about gravity, physics, machines, the politics of water?

“Did you learn something from this that you now want to examine?” asked David.

Wally paused. “My mind just went blank,” he said. “I want to get back to painting but I just don’t know how to do it.” He was interested in building more sculptures, he said, but he also felt an imperative to paint—after all, this was the RISD MFA painting program, not the RISD MFA wave machine program. The dilemma was causing him anxiety. “My brain is my own worst enemy!” he said.

Renaissance art academies flowed from medieval guilds, and functioned more like chambers of commerce than schools: if you were in one, you were already an artist in good standing. The first thing we’d recognize as an art school was founded in Paris in 1648 by the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, which set up in the Louvre to organize lectures and life-drawing classes, bestow honors and accreditation, and properly supervise the training of the country’s young artists.

Art school in America has never been quite that glamorous. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, when the first fine arts colleges opened their doors, aspiring artists were trained for one of two career options: technical illustrator or school teacher.1 Art students would be taught to draw in order to gain credentials as draftsmen for industry or, much more commonly, to pass their newfound drawing skills on to other students.

Today’s schools preserve the vocational function of their predecessors. In addition to the fine arts of painting, photography, printmaking, and sculpture, RISD offers degrees in industrial, furniture, and apparel design, animation, textiles, interior and landscape architecture, and art education, all rounded out by offerings in the humanities: history, anthropology, philosophy, literature, art history. An undergraduate can come out of the school having hit the trifecta of a marketable skill in the creative sector, a liberal arts education, and an enviable network of alumni.

At the graduate level, though, the idea of the vocational becomes a source of tension. A Masters program in the fine arts must prepare artists for professional life—but not exclusively, for reasons having to do with how art education was first incorporated into the American university system.

In Art Subjects, the definitive scholarly book on art education in America, Howard Singerman traces studio art’s journey into the mainstream of contemporary academia. To pass muster within liberal arts colleges (not just in freestanding art schools), art education first needed to distance itself from its historical attachments to industry and the teaching of teachers. This required advocacy and standardization; the College Art Association was founded in 1911 and linked studio art training to its more academically respectable sibling, art history.

Having secured a place for itself at the college level, the next step for art in America was to scale the walls of the university. In a historical repetition, MFA programs emerged in the postwar years as pedagogical degrees: vehicles for the accreditation of art professors. The MFA was—and still is—to art professors what the Ph.D. is to professors in the sciences or the liberal arts: the terminal degree in the field, required for job consideration at the college level. (The visual arts Ph.D., though now offered by a handful of institutions, is still widely and sanely disregarded as a bit over-the-top.)

Beginning in the 1960s, the meaning of the degree began to change. Artists started enrolling in MFA programs not just to get accredited for teaching but also to participate in the intellectual community they offered. Programs disseminated art knowledge from the creative hub of New York by bringing artists to campuses across the nation, in the form of the visiting artist lecture. As this happened, the programs established themselves as important sites of innovation within the field. More and more, one got an MFA not to be an art teacher but to be an artist.

As this happened, the MFA program changed the discipline of art. In fact, you could say that it made art into a discipline in the first place: a branch of knowledge complete with its own professional system, clearly limned evaluative criteria, and specialized language—not just a bunch of paint-spattered bohemians spouting off about inspiration and self-expression in Greenwich Village bars. Art education now contoured art practice along lines dictated by the university: discursive, polemical, self-reflexive. Art school was research, and its area of research was art.

In 1999, the year his book came out, Singerman lectured in the Columbia visual arts MFA program, where I was a first-year student. By that time, the idea of attending graduate school for art had gone from inconceivable to possible, and then had shot past recommended and was coming to rest somewhere near compulsory: if you wanted to be taken seriously as an artist, I heard again and again from professors and peers, you needed the degree.

The art market, too, had lately been taking an interest in art schools. From the perspective of the gallery, journalistic, and museological spheres, it was a fantastic idea: the MFA system regulated the production of artists. The schools turned out a crop of new talent every spring, their currency, so to speak, backed by the reputation of their degree-granting institutions. They were pre-socialized. They could talk competently about their work. They had a working knowledge of the codes, explicit or implicit, governing professional conduct in the art world. They could be relied on not to urinate on your carpet if you invited them to a cocktail party in your town house, but rather, as Jackson Pollock did at Peggy Guggenheim’s place in 1944, to use the fireplace.

What’s more, the MFA system provided a way to organize and therefore market young artists. The schools provided context, kinship, and affiliation for the new faces appearing in the galleries at the start of each season in greater and greater numbers.

In 1999, on the ascending slope of the first twenty-first-century art boom, serious amounts of money were starting to find their way into the art school sphere. Deborah Solomon of the New York Times went to Los Angeles to report on UCLA’s MFA program, which was churning out a lot of successful young artists; many of our peers were quoted in her article. Three years later, schools were said to have hot streaks in which students were snapped up by galleries before graduation, and dealers and collectors prowled thesis exhibitions in search of new talent. Two years after that, the management guru Daniel Pink would declare the MFA “the new MBA”: a twenty-first-century answer to the business administration degree prized by Wall Street talent spotters and corporate HR officers, and a potent source of creative thinkers to populate tomorrow’s business world.2

Fast-forward nine more years, to 8:45 on a Tuesday morning in Providence in the year 2012, and there were doughnuts and coffee in the second-floor critique room, and we had to get back to work.

Rachel had installed a group of mixed-media sculptures in a triangular zone in the northeast corner. Opposite, she’d arranged the folding chairs in precise diagonal rows. The largest sculpture involved a bundle of cloth tangled around a length of rope, all of it slathered in white acrylic gesso and then hit repeatedly with bursts of spray paint; the bundle was draped over an armature made of plumbing pipe, the rope trailing downward and coiling intestinally on the floor. The smallest was an unidentifiable white plaster thing, like the crushed skeleton of a bird, placed on a paint-daubed cinder block.

Rachel read her opening statement from a notebook: She gathers materials from thrift shops and home supply stores and subjects them in the studio to various sculptural transformations. She thinks about this process in terms of death, decay, and regeneration; the sculptures show “different degrees of dead.” The group pounced on this immediately: Why death? In what way do the sculptures evoke decay? Where did this morbid interest come from, anyway?

Today’s faculty lineup was different from yesterday evening’s. Since Holly and Duane had to leave after lunch to conduct a job interview for the Painting Department, the group included Judy Glantzman, a senior critic, and Dennis Congdon, the former chair. Dike Blair had agreed to take over Duane’s job as the customary timekeeper for the midterms. Since he didn’t want to feel like a fascist for cutting off the discussion at the thirty-five-minute mark, Dike had programmed an alarm on his iPhone. “That way it isn’t me—it’s the device,” he said.

Fashionwise, the faculty splits down cleanly demarcated generational lines. Chris, Kevin, and I, products of the 1990s, performed variations of a retro–New England collegiate look involving V-necks and Oxford shirts: Chris’s well-maintained, Kevin’s purposefully threadbare and tattered, mine in the nondescript middle. Duane, Holly, David, and Dike wear SoHo-in-the-’80s black; Judy and Dennis, the East Village alternative of bright, clashing colors. (On Tuesday, Judy wore a fuzzy yellow-green sweater with red clogs; Dennis, fluorescent green Nikes, a green-and-white-striped shirt, khakis, and a red baseball cap with the word BROWN on it.)

With few exceptions, the students dress in smart, metropolitan-twentysomething streetwear. During the reviews, pants were usually dark-rinse denim. The most common tops were heather-gray T-shirts (men) and silk blouses worn under a cardigan (women). The most popular shoes were black-and-white leather Adidases; I counted at least four pairs. The students were certainly not investment bankers, but they could be law students or baristas. If you were an HR officer, you’d hire them for most jobs.

This isn’t true of RISD students in general. Across the river, in the hub of the undergraduate campus, you see tattoos and piercings, baby-doll dresses and combat boots, thrift-store tees and mossy neck beards—in other words, the time-honored sartorial iconography of American art education. I did a studio visit with a RISD undergrad who channeled the young David Hockney so comprehensively—platinum bob, granny glasses, and all—that I almost asked for his autograph. I surmised that the graduate students, with a few exceptions, have either transcended the need to visually self-identify as art students or are engaged in some kind of reverse-fashion psych-out campaign.

Dennis Congdon scrutinized the little plaster thing on the cinder block. “In a way, the past life of these materials is the least interesting thing to me,” he said. Rather than repurposing thrift-store finds, he suggested that Rachel work directly in plaster.

Judy Glantzman said, “These are very female things.” They had fake flowers stuck in them, lots of violet and fuchsia, glitter. Holly talked about empathy for different stages of female life; one piece, she said, was like “an aging coquette.” Judy cited the work of minimalist sculptor Fred Sandback, who conjured invisible volumes in space using only bits of colored string; maybe Rachel should use different armatures than cinder blocks and lengths of metal tubing?

“I like the idea of rebar and steel—” David Frazer began.

“Because you’re a man!” Judy said.

The phone chimed.

Up on the fourth floor, a fellow student had stationed herself like a bouncer at the door of the critique room. Taniya wasn’t ready, she said, so if we could all wait a few minutes, please. At an inaudible signal from within, she waved us inside.

Around the room, newsprint drawings pinned to the walls and laying in heaps in the corners depicted bulbous female figures, some of them missing limbs. The centerpiece of the installation was near the windows: a big rickety cardboard thing like a stage or an altar, about the size of a refrigerator, with white butcher paper walls and a wobbly corrugated roof dangling from the ceiling on lengths of fishing line. Inside it, Taniya sat on a raised platform in a cardboard contraption that encased her legs; it looked like a cubist recliner.

Everyone who has ever studied or taught art has a favorite art-school performance art horror story; I once saw a man strap himself to a cross made of Erector-set parts suspended from the ceiling of his studio and writhe for hours in pretentious agony. So it was with a certain amount of apprehension that I observed Taniya in the box, waiting for her to do something crazy. But she simply held her pose for a couple of minutes, staring intensely at a point in space. People took phone-videos. At another subliminal signal, someone helped her down from the stage. She exited the room, then immediately returned, genuflected before the sculpture, and faced the crowd. “Okay, I’m done now,” she said. “This was my opening statement, so we can start.”

After the requisite fact-finding questions (Taniya’s work was inspired by a dream; she had been researching fertility goddesses), the conversation found its focus almost immediately: “Can you talk a little about your concept of skill?” David asked.

Regardless of whether Taniya’s work was good or bad, it didn’t show a lot of technical facility in the traditional sense. Her drawings were roughly executed, the single unstretched painting unfinished. By accident or design, the cardboard stage-altar contraption seemed one sneeze away from collapsing in a heap.

The question of skill is vexing to the culture of contemporary art education. It ties everyone in knots. Singerman devotes a lot of space in Art Subjects to the idea of “deskilling,” a term borrowed from the sociology of labor that describes the effect of automation on an industry’s workforce. For Singerman, the workforce known as artists had been undergoing a similar transformation for some time.

So, Taniya’s skillfulness or ineptitude was a tricky terrain that the group spent some time climbing around in. Did Taniya aspire to a level of competence that she was currently failing to achieve, or, as Chris Ho put it, “is the shittiness intentional?”

This opened the door to some riffing on the ad hoc quality of the work.

“The drawings seem intentionally spastic,” said Dike.

Kevin said, “If this really is an offering, then the Gods are going to be pissed.”

I chimed in and mentioned the Cabaret Voltaire of 1916, at which Hugo Ball recited nonsense in a cardboard bishop’s miter: was Taniya mocking the idea of religious ritual?

Taniya bore these remarks stoically.

“You should work really hard at being reckless,” said David Frazer, with sudden conviction. “You have what you need to work with. If only you would recognize it, and do it in a forthright fashion.” This was a surprise: I had pegged David as the last champion of skill against a legion of deskillers. But here he was chiding Taniya not for lacking skill, but for feeling bad about her lack of skill. “You don’t have the kind of background in Renaissance academic drawing that you think you would like to acquire,” he said. “Well, it’s too fucking late!”

Some discussion followed about whether or not it was too late for Taniya to learn to draw. Holly proposed that Taniya was functioning as a mystic, for whom the attempt to realize a vision transcended aesthetic concerns. “You’ve made a place where I can’t say if it’s wrong or right,” she said, and wondered about documentation: did Taniya record her performances?

“I did make a film,” sighed the artist. “I did make a film, but I did not like it.”

Because of the relatively quick historical development of the visual art MFA, you still often find students studying for a degree with professors who never got one. In the late 1960s, Holly apprenticed herself to a portrait-painter friend of her jazz-musician dad, then headed for New York. She kicked around a handful of schools before winding up with a BFA from the State University of New York at New Paltz but decided not to go any further up the educational ladder. “It was not an era where teachers got grad degrees,” she told me. She started teaching at RISD in 1993.

In group critiques, Holly prefers to give what she calls “the cold read”: looking at a student’s work before he or she has had a chance to talk about it and responding to it using the clues it presents. “No disclaimers first. Either it’s interesting enough to look at on its own terms, or let’s skip over it. Once we’ve had some discussion, they can throw in the fact that they come from four generations of architects.

“The whole crit thing is a psychological minefield,” she continued. “In teaching, you have to find ways to say things that are really honest. You can’t be too careful, or they don’t get what they’re there to hear. But you don’t want in any way to shut them down either. That’s the hardest part: to be incredibly blunt but not to be a negative voice they’ll hear later in their head that keeps them from doing something.

“We have a small-scale thing going on, and the intense community seems to reassure them enormously. They trust that they’re with people who are not torturing them for amusement—that it really is about helping them move through a series of revelatory steps.”

The day began to move quickly. Down on the second floor again, Page showed us a series of body-size abstractions in a conservative women’s wear palette of beige, navy, black, and gray. Her installation was completed by two photographs (a body scanner at an airport, a drone airplane), a potted plant, and a miniature camera mounted on the wall at eye level that observed us as we observed the art.

“We have to talk about the status of critique in this,” said Kevin. “There’s a presumption of criticality. I assume a pointed critique. The real conversation here becomes about critique, its various possibilities and failings, whether it is relevant.”

“Can you just say what you feel the content is?” asked Chris, exasperated.

“It posits something about its ability to posit something,” said Kevin.

The conversation fragmented into multiple simultaneous exchanges: Kevin and Chris, Holly and Page, Judy and David. Someone said, “The dialectic.” Maybe it was me; my note-taking broke down a little here. We headed upstairs again, through an acrid cloud of industrial disinfectant in the hallway of the third floor (“Did somebody throw up?” someone asked) to look at Bruce’s paintings.

The year before, Bruce had been making jokey paintings and sculptures: Mars Rovers, towers of pizza boxes painted in shades of gray, deadpan equestrian portraits. This semester, he was making relatively serious-looking abstractions with spray paint and an ingenious method involving aluminum foil: using a palette knife, you spread thick layers of oil paint across the foil, flatten the foil paint-side-down against the surface of a stretched canvas, burnish it with a putty knife, and then tear away the foil. This produces a finely textured surface with unexpected coloristic results. Art students often feel proprietary about techniques—the idea being to get your unique aesthetic product to the marketplace before your classmates can deliver theirs—but as soon as Bruce figured out the tinfoil thing, he shared it with all his classmates. This wasn’t out of altruism, he said; he wanted to spread the blame around in case the faculty hated it.

Judy Glantzman jumped in almost immediately. “What do you want us to experience?” she asked. “Is the subject of the work how we can figure it out?”

She mentioned an exhibition Bruce had done in New York in the fall. “I don’t know if this is a harsh thing to say, but when I went to your show, I didn’t stay. The tools didn’t become means within which to enter. At a certain point I felt, ‘Okay, I got it.’ I got the way you made them, and then I didn’t want to stay in them.”

“I feel like I’m at the edge of a bridge that hasn’t been fully constructed yet,” said David Frazer. The general feeling in the room was that Bruce’s earlier works, while perhaps unsuccessful as paintings, succeeded as works of art; these, on the other hand, were undeniably good paintings, but they weren’t very funny.

On the second floor again. To the east and northeast, big charcoal drawings of an apartment, life-size, on multiple sheets of paper, were pinned to the wall. Next to this were smaller drawings: a fishbowl repeated several times, a woman blow-drying her hair. The artist herself, Hilary, wore a tan sweater over a floral shirt and black jeans. After eight reviews, the arrangement of folding chairs in the second-floor critique room had begun to exhibit predictable behavior: it tended toward loose rows on the diagonal facing the southwest corner, so that now we were all facing the charcoal works.

I craned my head to look at a giant painting of a multicolored curtain, approximately life-size, on the wall opposite. In an experiment, I turned my chair around to face it.

“I see Roger has already made up his mind about which works are important,” said Chris.

We grabbed lunch from a Japanese place around the corner from the studios, and then headed back to the second floor again for Joe, a first-year student. Joe is very tall, and out of everyone in the group, he looked the most like an art student; paradoxically, this was because he was wearing a tie. A crude chair made out of concrete sat on the floor next to a chair-size cardboard box with the words SHAKER CHAIR stenciled on it. A monitor on a pedestal played a video of the artist making concrete tennis balls and reading a magazine. “It’s after Courbet’s The Stone Breakers,” he drawled.

“Joe, when you do DIY stuff, do you make it with intentionally poor craft, or is that the best you can do?” asked David Frazer. Primed by the deskilling dustup in Taniya’s critique, Joe answered promptly that he intentionally made things poorly. In fact, the concrete chair was a little too sturdy; in order to work as a sculpture, he said, it really ought to fail more as a chair.

Discussion wheeled around the question of whether Joe made his willfully sad-sack sculptures in character as “Joe the inept craftsman,” rather than as Joe the smart young artist in one of the nation’s top-ranked art schools. If so, was this distinction consistent enough? The concept wasn’t entirely clear to anyone, it seemed. “You’re making irony of the clumsy builder?” asked Claudia.

Judy thought that Joe’s work exemplified the prevalent mode of art-school art: smug self-awareness. She called the work “nudgy-nudgy.”

“What do you want from us?” she asked. “What do you want from me, as the token woman of the moment?”

As if drawn by a magnetic force, Kevin mentioned Joe’s tie. Was Joe-with-the-tie a persona, one that could be delineated from plain-old, open-collared Joe? Would the work be different if Joe wasn’t wearing a tie for his review? Is it meaningful to pose the question in the first place? Later, Joe told me that having worked as a museum guard and at various art-administrative positions over the years, he was simply accustomed to wearing a tie on special occasions such as these.

An Art History–Trained Conceptual artist in a faculty of dedicated painters, Chris Ho is an anomaly in the RISD Painting Department. He started out teaching the seminars Art Since 1945 and Contemporary Critical Issues, two mainstays of the American undergraduate art school humanities curriculum. “The tradition I was telegraphing was one in which painting somehow ended in the late fifties and early sixties—and then everything else happened,” he said.

I asked him what he thought about RISD’s critique format. “It’s not quite a tennis match,” he said. “It’s more like cooking, maybe . . . Its also very courtly, very seventeenth century. It’s not passion that gets you through a crit. It’s articulation, spacing, rhythm, phrasing. People who are great at crits understand these things.”

Chris has a programmatic, optimistic approach to teaching art. “It’s like classic enlightenment philosophy. I’m going to treat the students as peers—as if their work is the best work out there, and I’ll respond to it as such. That fiction, or semi-fiction, will translate into reality, so long as I maintain it long enough. So if we have two years, I will treat them seriously for two years, as real artists, and hope that at the end they will have become that.”

“Isn’t it great to be around the next generation?” he remarked. “They know more than we do. They just don’t know they know it yet.”

I was on the fourth floor looking out the window through a telescope aimed at a brick wall across the street; a goofy chalk drawing of a hand gave me a thumbs-up. Rachel’s work was composed of tiny, flea-circus arrangements of painted paper and debris; they were pinned to the walls, clustered in piles on the floor, and gathered on the windowsills, interspersed with pieces of optical equipment. Two large pen-and-ink drawings next to the door resembled the moon; in fact, Rachel made them by looking through a telescope at an orange.

Judy Glantzman mentioned the work of the Swiss installation artist Pipilotti Rist. Typically, once somebody mentions an artist or a work, everybody starts doing it, and the critique becomes an exchange of proper names. Here, we volleyed Duchamp’s Étant donnés, the miniaturized sculptural worlds of Charles Simonds, Hilary Harkness’s fanatically detailed paintings of submarines. “It’s amazing that nobody has kicked these over,” Judy said. And, as if on cue, Francisco stumbled and nearly wiped out a pedestal topped with a miniature diorama. Joe grabbed his arm and averted the catastrophe.

Francisco wore a black T-shirt with the head of the Statue of Liberty on it. He had done a project during his first year in which he painted the Statue of Liberty seventy-eight times. This semester, he presented a complicated installation-in-progress including two giant paintings, a scaffold, a painted plywood floor, and a tailor’s dummy with a dress made up of cut-up canvases. All of it was covered in jagged black-and-white stripes, much like his shoes—those ubiquitous leather Adidases.

Francisco had grown up in Mexico City and moved to Texas when he was six. When he’d studied art in college, he’d learned that Abstract Expressionism was the iconic visual language of American painting. “My teacher was so into it,” he recalled. Lately he’d been looking at the dazzle camouflage used on British warships during World War I, the source of the patterning in all of Francisco’s work.

“Koons, or Hirst, dazzle-decorated an art dealer’s boat,” Chris Ho pointed out.

“Do you mean the image to be readable?” asked David Frazer of one of the big paintings. “I assume it’s a combination of images. Is that intentional? Is that a car . . . ?”

“I see a bag with—oh, I see a car,” said Judy.

“We’re all looking for proper nouns here,” said Chris.

We wondered about the painted floor: “It’s a stage,” said David. “I expect a performative condition—some sort of rock band.”

David’s key word in critiques is condition, which can be coupled with different modifiers: accidental condition, preservation condition, condition of animation. It’s indisputably his word, though other people in the program helplessly and unconsciously pick it up; for weeks after the reviews, I found myself incorporating it into my own teaching patter. The genius of condition is that it’s sufficiently versatile to encompass a whole range of functions—or rather, a whole range of conditions—but has enough mystique to avoid sounding flat or generic. Condition is to Frazer what Being was to Heidegger.

David went to RISD as an undergraduate in the 1960s. He then got an MFA at the University of New Mexico, and shortly after that landed back in Providence with a sabbatical-replacement job teaching in the RISD freshman Foundation Studies program. He’s been at the school for thirty-four years.

“It was a very ingrown group of guys, “ he said of his professors then. “They were serious artists but not terribly engaged as teachers. There was sort of a tacit agreement between the faculty and us that if we left them alone, they’d leave us alone.”

How different this was, he said, from the intimacy of teaching at the school now, especially at the graduate level, where teachers and students are expected to articulate anything and everything about the messy process of making art. Not only has the role of the art instructor changed (from silent and inscrutable icon to something more like a full-time life coach), but also the entire culture of art-making has shifted on its conceptual axis.

“The zeitgeist of my generation tended to be that art is a serious and painful activity that one engages in despite the fact that it is,” David said. “Now, all these guys embrace the potential of art as much as they embrace other forms of entertainment. They recognize and believe that there’s no problem with generating work that’s just provocative, or simply entertaining.”

When we arrived on the fourth floor, Art instructed us to arrange the chairs in a circle, facing inward, group-therapy style. We were surrounded by murky abstractions: bedsheets that had been tie-dyed and tacked to the walls, canvases cut apart and sewn back together in crude strips, stretcher bars burned black and assembled into sculptures.

Art had a shaved head and wore gray jeans and a severely starched white dress shirt under a black V-neck sweater. The whole outfit cost him twenty dollars at Goodwill, he told me. He announced that he had no opening statement; he’d rather hear what we had to say and then “open it up to questions.”

“One thing I like is they’re so depressing,” said Dike.

“There’s a grimness here. It’s like breaking rocks,” said Kevin.

“The grimness is generative rather than recursive,” said Chris.

“A morose nostalgia,” said Duane Slick, who was just back from interviewing a job candidate.

Michelle, a soft-spoken second-year student, lodged an objection: “I don’t mind grimness at all, but it seems like you’re attracted to the aesthetics of what’s grim and what’s dark. I’m almost put off, a little bit, by your attraction to the glamour of what’s sad.”

For the remainder of the review, we parsed the negative emotions. The faculty, who had been flagging in the mid-afternoon heat, suddenly perked up to discuss the differences between depression and morbidity, melancholy and sadness.

We ended the day with Kimo. Like Joe, he’d dressed up a little for the review; he wore a sweater vest and a bolo tie with a piece of agate, or quartz, for a clasp. A big guy with small, bookish spectacles, Kimo came to RISD after a long postcollege stint as a nature guide in the Grand Canyon, during which time he painted en plein air. Here, he shifted into abstraction, making small canvases in which acrylic paint pools and splurges around, and then carefully repeating those chance shapes on other canvases using stencils and tape. “I’m interested in what counts as nature,” he said circumspectly near the beginning of the review.

David Frazer was up and circling the room. He riffed on the difference between the stenciled paintings and the freehand, drippy ones, the ones that had landscape references and the ones that were purely abstract. He wondered if Kimo’s process could more closely mirror the actual processes of nature.

Meanwhile, Judy Glantzman was cocking her head to one side in the direction of two mid-size canvases on the northwest wall. “You know, it’s funny,” she said, “when I look at these paintings I like them horizontally.” Everyone tilted their heads like Judy was doing. She asked permission to rotate one of them, and, liking the results, turned another. “There!” she beamed.

At 4:15 I went back to the hotel and fell asleep. Later, I woke up and tried to find some dinner. Providence has gone through a bit of urban renewal in the past decade, as indicated by the boutiques and cobblestone sidewalks in the arts district, where the studio building is—though many of the storefronts are vacant, or else filled with stop-gap devices like temporary art exhibitions or advertisements for “special event rentals.” Kevin Zucker told me that the street used to be nothing but massage parlors. On the way back to the hotel with a sandwich, I looked for the chalked thumbs-up graffiti I’d spied through the telescope during Rachel’s review, but I couldn’t find it. Either she had come down in the meantime and conscientiously wiped it off the wall or I’d misremembered the direction of the telescope. I stood in the parking lot long enough for the attendant to come out of her booth and ask me what I wanted.

Art education has always had its critics, and most of them have been art educators. After all, critique is the backbone of the system. The attacks on art education launched from within the walls of the art academy make the ones leveled at it from without seem trite and ineffectual—nothing more than variations on the classic formula You can’t teach someone to be an artist. You can; people do; artists have taught artists since there were artists.

Singerman ends Art Subjects, a largely dispassionate book, with an unexpected cri de coeur for the casualties of art education. “I cannot, however, let the cruelty of current art training go unremarked,” he writes, before enumerating such pedagogical excesses as the “harshness” of the structure of critique, in which criticism of artwork slides easily into ad hominem attacks on the artist; the existence of “cliques of students and sometimes faculty who control the local circulation of discourse, wielding it as a weapon”; and, cruelest of all, the sorry fate of students who “fall through the cracks of teaching: those who leave art school with neither the self-awareness that would allow them to thrive as artists in the professional sphere, nor the technical skills that would let them to paint or sculpt or draw as a fulfilling, personal pastime.3 For these students, Singerman thinks, art education is the ruination of art.

The tenor of the internal critique of art school changes with environmental conditions in the art world outside it. Circa 2000, the year I left school, the art pedagogy panels and faculty hand-wringing sessions in top-ranked programs circled, optimistically, around something like the age of professional consent: how young was too young to groom someone for art stardom? Should students be exhibiting and selling their work while still in school, or should they wait at least until they graduate? If, according to Singerman, the field of research in art school is art, and art is primarily organized as a market, then the obvious danger is that art school becomes nothing more than a form of market research.

On the other end of the last decade’s art boom, the problem with the MFA seems more serious. After a run of years in which a degree from a prominent school seemed to lead effortlessly to a seat at the art world table, the academia-market partnership began to fatigue. The redistribution of wealth in the contemporary art system after the financial crisis of 2008 left far fewer spaces for young artists in galleries, less funding for them in the institutional sphere, and fewer grants, residencies, teaching jobs, freelance writing gigs, assistantships, paid or even unpaid internships. The three numbers that never seem to drop are tuitions, big-city rents, and the total student debt.

A few years ago, Coco Fusco, an interdisciplinary artist and professor at Parsons in New York, issued a scathing broadside against the MFA in the independent monthly paper the Brooklyn Rail. Citing the escalating cost and diminishing professional returns of art school, she called for an inquiry into “the politics of charging vulnerable young people six figures as an entry fee into a milieu that cannot sustain most of them.”4 Recalling the unofficial apprenticeships she undertook in New York in the 1980s (basically, hanging around the studios of older artists), Fusco lamented the translation of identical experiences into components of the MFA curriculum—the difference being that the student now pays through the nose to be mentored by older artists. She asked:

How much longer should we endure our own version of a subprime loan crisis before we consider how art schools seduce relatively inexperienced consumers into borrowing huge sums for degrees by trafficking the same myths about art and the art market that they purport to “deconstruct” in required lecture classes?5

The problems that Fusco described extend much further than art school: skyrocketing operational costs, administrative bloat, and unreasonable loan policies plague the American educational experience across the board. But the MFA system in particular finds itself navigating between equally dystopian possibilities: the wholesale default of art education into career training, where success and failure are measured strictly in terms of graduates’ performance in the art market; or its elevation to a pure research degree offered at onerously professional-school prices. The economic realities of art school form the second curriculum of every MFA program in America, an undercurrent of unease in each studio visit and seminar session convened.

Like David Frazer, Kevin Zucker attended RISD as an undergraduate; all his senior colleagues were once his teachers. As an artist whose professional life has unfolded through various institutional affiliations (he began showing his work prominently while still in graduate school), he was uncomfortably aware that he exemplified the promise of a certain kind of success that still attracts many students to the MFA, in a very different professional climate than the one he witnessed.

“I didn’t go to graduate school expecting to have the experience that I did, or expecting it to have the effect on my career that it did,” he said. “The fact that that happened to a few of us may have really shaped expectations for a number of years. I think those expectations have changed. There’s been an adjustment towards a more realistic understanding of what an art career is supposed to be.”

Zucker is keenly attuned to the critique of the MFA that has unfolded in art academia over the past decade. “I believe that anyone teaching in art school who isn’t aware of, and therefore at pains to avoid, the Ponzi-scheme worst-case scenario is doing the students a disservice—and that these tensions are things that should be openly discussed in the classroom,” he told me. “But a pet peeve of mine in this whole conversation is that we too often group all MFA programs into something monolithic. I believe, or hope, that there are real differences between programs, and that those differences actually have significant ramifications—pedagogical, economic, and therefore ethical. These are almost always glossed over. You rarely see the potential benefits and downsides of grad programs being enumerated together in a way that would help young artists make better decisions, based on something other than fantasy and paranoia.”

In my informal polling of the RISD MFA painting classes of 2012 and 2013, no one expressed any reservations about the program. The students were committed to the task at hand: understanding the history and current dispensation of the field of contemporary art and finding their own place within it, all in the span of four semesters. They were conscious of the long odds of success in the professional art world and of the dire financial stakes of art school—a theme reiterated so often inside and outside the academy that it has now taken on the quality of a mantra.

They were also, predictably, somewhat reticent to talk about money. “That’s definitely kind of worrisome,” Kimo told me over a beer on the Lower East Side during the summer. “The idea of finance is a weird thing in the art world in general, especially among artists. You don’t know who has a trust fund and who doesn’t, and it’s just uncomfortable for everybody to talk about that. It just becomes about who has the opportunity to make it post-school. Maybe I’m just perpetually optimistic.”

Page, who waitressed in Brooklyn during the four-year interim between college and grad school (“I lost track of how many restaurant jobs I got fired from!”), wondered if the brevity of the program, its cost, and the desire on the part of everyone for the students to thrive in it all conspired to soften any actual criticality. You can’t run a successful MFA program if students leave feeling demoralized—word will get around.

“There does come this point where the teachers have invested so much in you that they almost want to believe that they’ve been effective—and so they approve of what you’re doing,” she said. “I almost wonder if there isn’t a bit of . . .” She trailed off.

On the other hand, Art wasn’t having any of this line of questioning. “Generally, these conversations about ‘Is the MFA relevant anymore? Should people be getting MFAs?”—I think that’s a lot of elitist bullshit. I’m the first person in my family to go to college,” he said flatly.

Contemporary art is a time machine set exactly one second ahead of the present. Contemporary art is a sphere whose circumference is everywhere and whose center is unaffordable. On the final morning of the reviews, after reducing the volume on his squelching videos, Doug gave us a little introductory material about the rec room. Its elements were autobiographical, he said. The cartoon I had been attempting to interpret was “Amazons Just Wanna Have Fun,” episode 7, season 2, 1986, of Hulk Hogan’s Rock ’n’ Wrestling.

Dennis Congdon, in an orange baseball cap and a brown cardigan, migrated from a seat near the windows to two sculptures near the door with video monitors in them. On one screen, a figure with a big, papier-mâché head stood in a field; on the other, it tap-danced in a tuxedo against a white background. He addressed the group with genuine enthusiasm.

“I want to make a pitch for these remarkable, plywood-enclosed video screens with underwater accoutrements,” he said. “What’s set up is a kind of fantastic framing device that’s inseparable from the image. I wanna hang around that big time.”

Michelle, Anthony, Jonathan, and Lauren

“How do you think we should sit? Do you think it should be all willy-nilly or . . . ?” Michelle waited for the stragglers to make it up to the fourth floor. The room was hung with small portraits, all of which she had painted from found photographs or from other paintings: Langston Hughes, hands steepled beneath his chin; Naomi Campbell posing in front of a sketched-in palm tree; two versions of a Dubuffet self-portrait; a Picasso bather; Queen Latifah in a black-and-white-patterned jumper.

“I thought your first question, about where we should sit, is an interesting one and appropriate to what we’re seeing on the wall,” said David Frazer.

“What’s the title of your thesis?” Duane Slick asked Michelle.

“‘Portraits.’”

“Not much of a clue there, Duane,” said David.

Michelle elaborated on her idea of portraiture. The pretense of a traditional portrait is to show the individual qua individual, she said. “But I want to show an individual tyrannized by their environment, an individual dependent on their social network. You”—she gestured to David—“are ‘David Frazer, my teacher at RISD,’ not just ‘David Frazer.’”

“The way you state your thesis is kind of stark and unyielding,” said Chris.

In an aside, Duane asked Dennis Congdon why Michelle was painting African American people. This was an obvious question. The current student body included Mexican American artists, First Nations artists, Filipino American artists, artists from India, Indonesia, and Chile, Jews, Wasps, and a Mormon, and the only African American artists in the room were Langston Hughes and Queen Latifah, there on the wall. But the conversation veered back to the now-familiar ground of success and failure in painting. “You have to try to make better paintings fail,” Holly concluded, and we bustled downstairs again.

The other wrong idea I had about graduate art school, besides the one about how people there talked about art, was this: I imagined it as a utopia of experimental fuckaroundery. I thought you went there, holed up, and went completely avant-garde. You did forty-eight-hour spoken-word performances in which you read from the phone book, or dropped acid and methodically licked every square of linoleum on your studio floor. Or you did nothing: doing nothing was perhaps the only thing that couldn’t be recouped as a form of production and talked about for thirty-five minutes—and even that wasn’t a sure bet.

I didn’t do any of this. Neither did my classmates. We worked, diligently, sometimes frantically, always mindful of the clock. Even the people who slacked off did so demonstratively, intentionally—as art; they practically put it on their CVs.

So I wondered, eventually, how I’d come by this anachronistic idea about art school. I’d probably absorbed stories about Black Mountain College, the experimental enclave at which Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, and Merce Cunningham came together in a short-lived post-Bauhaus summer camp; or CalArts in the seventies, where artists like John Baldessari brought Conceptual art squarely into the curriculum and energized both. These hazy, half-mythological visions brought me to art school. This was like watching Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific and then deciding to join the navy on the basis of the experience.

It’s possible that the dream still lives on in today’s artist-run schools, the do-it-yourself alternatives to the MFA system of which there have been an explosion in the past decade. There’s Los Angeles’ Mountain School of Arts, a free, volunteer-driven enterprise housed in a bar in Chinatown, and the Public School, an “autodidactic” proposal-based network of reading groups that now takes place in eleven cities worldwide. Most of these, however, present themselves as more academic than the academy, with a punitive self-seriousness intended to reproach the university system for its descent into commercialized education.

But maybe I should call this dream uchronia, not utopia: a no-time existing apart from the regimented pace of contemporary life. Because, observing the day-to-day operations of an average program, it’s easy to see that the visual arts MFA is conditioned far more by time than by space. Faculties jog between undergraduate and graduate duties, shifting mental gears between the routines of Introduction to Painting and the more nebulous intellectual space of grad-level studio visits. The students, meanwhile, have two years to absorb the conceptual framework and professional codes of contemporary art before they are shunted out into an unregulated industry teeming with competitor-peers. Between critical issues seminars, visiting artist lectures, teaching assistant duties, organizational meetings with the curator of the end-of-year exhibition, and the preparation of their 2,500- to 3,000-word thesis, they’re scheduled within inches of their lives.

I looked up. Dennis Congdon was rubbing the surface of one of Anthony’s mural-size, inkjet-print and oil paintings, trying to determine what it was made of. Holly had been quiet for a while, regarding a vertical painting on the north wall: a can of white house paint sitting atop a jumble of soldiers and landscapes, overlaid by a schematic of jutting lines.

“What does that paint can stand for, in that painting?” she asked. Anthony didn’t answer.

“Stop squirming! Is there a political implication to this paint can or not?” Still nothing.

“I’ll tell you how I read it,” she said and approached the painting.

“Holly, tell us!” someone shouted.

“I see this painting as super-American. The notion that we can clean up our mess by keeping the paint fresh. It’s a political one-liner to me. There are these ‘situations,’”—she gestured toward the jumble of images at the bottom of the canvas—“that’s ‘all wars’ down there, and a structure that implies entrapment, in which we can keep our mess. And then”—up to the top of the canvas again—“the miracle paint can.”

A beat of uncomfortable silence passed. Holly backpedaled slightly. “If that isn’t in this painting, I should seek help.”

Jonathan’s paintings, next to last, were brushy abstractions in a light palette. He told the group that he’d been painting representationally last semester, but that this semester he wanted to forget what painting was supposed to be—to start over from scratch.

Dike said, “This may be too early in the conversation, but did you fall under the spell of Raoul de Keyser?”

“Yeah, I tried not to look at him for a few months,” said Jonathan of the newly fashionable octogenarian Belgian painter.

David Frazer got up to look at a thick, gray-on-gray painting. A tiny piece of blue masking tape had been casually half-stuck to the surface of the canvas, right near the center.

“Where the hell did that thing come from?” he asked. “I want to rip that little piece of shit off this painting, because that was a good painting before you added that.”

Over the course of the reviews, I’d noticed that we often spent a minute or two at the start of a session determining what was or wasn’t part of the art. Not that we were hoping to arrive at a philosophical definition; simply in the interest of time, we wanted to know what we were contractually obliged to discuss.

So the tape presented a problem. A foreign object in middle of the work of art, the tape took on an outsize, irritating significance. It threw a monkey wrench into the whole art/not-art algorithm we’d been using up to this point. I had a brief, vivid hallucination, no doubt brought on by exhaustion, in which David pulled the piece of tape off Jonathan’s painting, and the painting just fell apart—as if the tape were the only thing holding it together in the first place.

Then I wondered what would happen if all of Jonathan’s paintings suddenly disappeared—would we talk about the walls? The critique might stop in its tracks, but maybe it would simply turn to the next available object, and then the next, picking up momentum as it did: from the walls to the room, the room to the building, the building to the school, the school to the MFA system, until, if there was enough time, we ultimately encountered the entire economy of art education and our vexed roles within it—the whole art school condition, as David might put it.

I thought about how most aspects of graduate art education are now geared toward the thorough professionalization of the student—but not critique. For all the ways it resembles a focus group, critique does not, in fact, help students refine a sales pitch for their art or give them instructions on how to make it more marketable. It shoots past these goals and bravely heads for the further terrain where art properly begins. It would also be endless, except for the thirty-five-minute alarms set to keep the thing from getting out of hand.

But then it was suddenly over. As we headed downstairs for the last review, people were chatting amiably, discussing plans for the rest of the week. Lauren showed a suite of bright-fabric assemblages—they looked like geometric abstract paintings from the sixties done up as quilts—and some big inkjet prints of pictures of plants and houses clipped to the wall. To the northwest, a video monitor showed split-screen footage taken out a car window, the image repeated, inverted, and mirrored so that the passing traffic converged at the center of the screen.

“I continue to be interested in the indefiniteness of a lot of the elements, and of the relationships between the elements,” said Kevin, “and that you don’t know about them. Part of me wants to say, ‘Ante up.’ Indefiniteness has to become content.” The review ended there. People checked their phones, put on their coats, and bustled out of the room for the next class or meeting or train.