In the late 1920s, a Kansas-born critic named Thomas Craven mounted a campaign against the influx of modern art from Europe. He urged American artists to “throw off the European yoke, to rebel against the little groups of merchants and esoteric idealists who control the fashions and the markets in American art” and to forge their own, properly nativist vision.1 He championed a group of painters from the heartland—Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, Grant Wood—who depicted traditional scenes of rural American life: rolling prairie landscapes, farmers toiling alongside their livestock, and honest folk walking small-town streets. Their paintings were like tall pitchers of lemonade for an art-going public parched by the Great Depression.

Craven was a man of strong passions, and most of them were negative. He was not only anti-European but also anti-Semitic, anti–woman artist, anti-photography, and anti-abstraction as well—the kind of advocate an art movement is unlucky enough to have. For Craven, the Regionalists (as these artists became known) had “taken art from the hothouse to the open air, away from the tender nursing of Bohemians and playboys, and . . . placed it within reach of the people.”2 And because these Bohemians and playboys, merchants and esoteric idealists, all tended to live in one particular city, Regionalism constituted the first critique of New York as the center of the American art world.

It was just the beginning: subsequent decades would see the critique renewed, with different political aims and competing visions of how artists might otherwise distribute themselves geographically around the country. And over the course of eighty-five years, the landscape of American art has certainly changed. Between art education in the university system, the propagation of art culture through the digital media, and the well-documented capacity of contemporary art as a tool for urban renewal, art is embedded in the mainstream like no other time in history. The country now boasts myriad enclaves of art activity, pockets of vigorous production emerging around the multiplying nodes of the contemporary art network. Show me a college town with an old bank building and a bunch of empty warehouses, and I’ll show you an exhibition center and a local scene waiting to happen.

But despite a history of proclamations to the contrary, the truly local turn in American art seems always just about to occur. By and large, ambitious artists still move to the market centers of the art world—and if they don’t, they worry that they should.

It’s no great mystery why: once there, they have distinct professional advantages over their peers in smaller art centers. In an industry still largely committed to doing its business face-to-face (in physical spaces, and with, for the most part, physical objects), they have easier access to the centers’ commercial gallery system, nonprofit institutions, and arts media. By and large, these structures still dictate value in contemporary art to the rest of the country; an artist from elsewhere may need to move to, and succeed in, New York or Los Angeles before she’s taken seriously at home.

The benefits don’t end with the strictly professional. Artists in the major arts hubs exist in larger creative communities with more durable support structures and enjoy greater opportunities for critical dialogue. They’re less subject to the whims of the relatively small group of critics, curators, and dealers who determine what gets shown in a smaller art scene.

The only downside is that they pay for it. And as the market centers reach potentially terminal levels of costliness, it may finally be time for everyone to consider this alternative arrangement: distributed, small-scale art communities whose cost of living doesn’t drive artists into bankruptcy—but at the same time allows them to achieve visibility in, and interface productively with, the massive complex of ideas, institutions, and markets that constitute the contemporary art world. In theory, this has been possible since before New York took the mantle of world art capital away from Paris, but practice is always trickier than theory.

I was thinking about this as I flew into Milwaukee. I’d scheduled a long weekend there in the fall of 2012 to investigate precisely such an example of ambitious, locally oriented art production, or something approximating it. My hopes were high.

Milwaukee has roughly the same degree of art infrastructure as a dozen other American cities. It has two college-level fine arts programs; a mid-size museum; an art-education nonprofit, the Walker’s Point Center for the Arts; and a small contemporary art kunsthalle, the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee’s Institute of Visual Arts. A handful of commercial galleries cater to the occasional local collector, and smaller artist-run spaces offer exhibition opportunities for local artists, though not much in the way of sales.

While the city is number one in American beer-making, it has never cut much of a figure as an art town. But Milwaukee had been in the back of my mind since 2006, when a group of young artists decided, against all conventional wisdom, to hold an art fair there.

It was a banner year for the international art fair in 2006. Cities like London, Moscow, Dubai, and Palm Beach had recently joined the circuit, and fairs in Shanghai, Abu Dhabi, and Berlin were in the works. The old stalwarts were expanding, accruing smaller satellite fairs and then satellites of the satellites so that visitors to Art Basel Miami Beach in December could also explore NADA, Scope, Pulse, and Aqua by wandering from convention center to hotel to warehouse to tent city, taking in that season’s art offerings while sampling free promotional cocktails in a state of sun-soaked distraction.

Seen from afar, the Milwaukee International Art Fair looked a lot like a put-on. Forgoing the luxury-tourism cache of most fairs, it was scheduled for an October weekend at the Falcon Bowl, a beer hall/bowling alley/home of the fraternal order of Polish Falcons of America, Nest 725, in the neighborhood of Riverwest. The name of the fair was slyly self-deprecating (International?) and funny even on a phonetic level, containing that terminal “key” that one comedian or other called the most humorous sound to the anglophone ear, especially when found in a place-name; Milwaukee shares this with Albuquerque, where Bugs Bunny took his famous wrong turn.

As it happened, the funniest thing about the Milwaukee International Art Fair was that it really was an art fair—small but real—and an international one at that. Visitors could sample the wares of a concise selection of galleries from Switzerland, Canada, and Puerto Rico, not to mention Los Angeles, Miami, and Chicago. The eminently cool New York gallery Gavin Brown’s Enterprise participated, as did the venerable nonprofit exhibition space White Columns. White Columns curator Matthew Higgs included a paean to the experience in his “Best of 2006” wrap-up article in the December Artforum. “The Milwaukee International proposed a viable, self-sustaining model of culture, one that was rooted not in social or economic one-upmanship but in the pleasures of self-determination, friendship, and cooperation,” he wrote. A little art was sold, most participants broke even, and some people actually made money.

The Milwaukee International had been a triumph of shoestring event planning. The organizers charged galleries $150 for a booth (compared with $30,000 to $50,000 for a space at New York’s Armory Show), used the entry fees to rent the Falcon Bowl, and housed visiting art dealers and artists in their or their friends’ apartments. Good luck helped too: earlier that year, the Art Chicago fair had imploded after a last-minute labor dispute. When a 25,000-square-foot tent spectacularly failed to materialize in Grant Park by the scheduled opening, the Art Chicago people were left with a whole lot of suddenly useless freestanding walls. They donated them to the Milwaukee kids, five or six local artists, who unloaded them off a flatbed into the Bowl with the help of the two truck drivers.

Though the Milwaukee International group’s fair-making ended in the wake of a downturn in the art market a few years later, their campaign had the effect of substantially raising the profile of the city and its small cadre of contemporary artists. People started showing up to see what the fuss was about. Artists came from out of town to make shows. Journalists checked in to dig the scene. Six years later, the question was, if Milwaukee truly is a model of a small, self-sustaining contemporary art center, does the model actually work?

I visited the city a few days after Hurricane Sandy hit the East Coast. In Brooklyn, the neighborhoods of Dumbo, Sunset Park, Gowanus, and Red Hook were underwater; the Rockaways were underwater and on fire. The lights were out in Lower Manhattan, and water filled the basements of Chelsea galleries between Tenth Avenue and the West Side Highway, doing serious damage to a lot of artwork. This was devastating for the artists and for the dealers without insurance, but with peoples’ houses burned to the ground, it was hard to get too upset over some contemporary art, everyone pointed out. On the way to Newark airport, I passed long lines of cars on the roadside waiting for gas.

The Milwaukee airport, though, was a tranquil vision of normality. At the car rental place, they gave me a bottle of water and directions into town, where I soon located Milwaukee’s hippest (and practically its only) contemporary art gallery, the Green Gallery, and its proprietor, John Riepenhoff.

The Green Gallery is a wedge-shaped, single-story brick building that sits a few blocks from the lake on North Farwell Avenue. It has a small paved lot out front, with a carport and a big, blank, kelly green rectangle as a sign. The building might have been a gas station or a dry cleaner’s shop in a previous life.

John met me inside the door, wearing an orange camouflage Green Bay Packers hat, a white shirt with a pink and turquoise geometric motif, and white jeans. He’s in his early thirties and has long, very fine, straight blond hair and rectangular metal glasses with thick frames. Behind the desk, a young intern named Madeleine was listening to NPR. Obama was campaigning in Green Bay, and he’d just gotten the endorsement of Packers safety Charles Woodson; this was a coup for the incumbent in the Republican-controlled swing state. “We have this awful governor, Scott Walker,” John explained.

Over the past few years, John had been making sculptures called “Art Stands”: pairs of mannequin legs, dressed in jeans and sneakers (usually his own) that hold up paintings or sculptures by other artists. They’re perfect portraits of the artist as social facilitator, small-time impresario, and, in many instances, tireless schlepper for his friends and colleagues. He’s a walking reminder of the first thing you need to get a small art scene off the ground: a really enthusiastic booster.

John grew up in Wauwatosa, a Milwaukee suburb, where his father was a sports editor for a newspaper. He studied art at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and after graduating met brothers Tyson and Scott Reeder, both artists who’d recently moved to the city to participate in an Internet television venture. Later, they’d all work together on the Milwaukee International and a host of other Milwaukee-centric art activities, but at first John worked for the Reeders as a studio assistant.

The first location of the Green Gallery, an attic on East Clarke Street opposite the Falcon Bowl, had sky-blue walls, ceiling, and floor; John decided to leave it as is, liking the cognitive dissonance the combination of the color and the name of the gallery produced in its visitors. Because the gallery wasn’t a moneymaking proposition—he supported himself by doing art direction and prop master work on local films—he was free to develop his program at his own pace. He was also under no obligation to work with people he didn’t like. “I try to put people who are interesting and nice into the gallery and see what they do,” he said.

He invited a group of decorative artists specializing in faux-finishing to paint murals on the gallery’s walls. He hosted the sixth annual Umali Awards, an absurdist presentation by local artist and professor Renato Umali honoring winners in categories like “Most Frequented Restaurant” and “Most Famous Person Spoken To.” He gave an exhibition to Thurman O’Herlihy, a gifted nine-year-old from rural Wisconsin. Sometimes he found interesting, nice people who would never in a million years think of themselves as contemporary artists and tried to convince them that they were and that they should do a show at his gallery. This sometimes backfired, he said—“but making public mistakes is good for everybody.”

The gallery moved into a larger space in a building on East Center Street in 2005. The new location also featured Club Nutz, an open-mic comedy club devised by the Reeders that served as a convenient if limited-capacity venue for after-parties. The room, into which everybody crammed to drink beer and take turns telling bad jokes, was the size of a broom closet, with a fake-brick backdrop and a microphone.

In 2009 John brought in his cousin, Jake Palmert, as a business partner and opened a second space; we were standing in it. It looked more like a proper gallery than the old one did, and they treated it as such: a commercial enterprise, doing business both in town and on the art fair circuit, that would also facilitate an intellectual exchange between local and international art.

The nice thing about a small scene is how manageable it is: there’s usually just one of everything. But that’s the terrible thing too. The Milwaukee art scene had suffered a major loss that July, when the artists’ building on East Center Street burned down. The fire began in the auto shop on the ground floor and took out sixteen artists’ live/work spaces and five galleries, among them the Green. The arts community rallied, arranging donation programs with local businesses, temporary apartments and dorm rooms, and fundraisers for the victims of the fire. John, who had almost been at the point of being able to live off the gallery, started saying yes to film jobs again.

Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930) is the most iconic product of the Regionalist movement, and it certainly cracks the top five of famous twentieth-century American paintings: the cue ball–bald farmer with the pitchfork, his dour wife, sister, or daughter—you’ve seen it. Looking at it, you may suspect that Wood held a more dialectical vision of the relationship between Bohemia and Main Street than Thomas Craven did; American Gothic, with its perfect deadpan tone, seems not so much like corn as pure, homespun camp.

Also unlike Craven, who launched most of his fuming anti-coastal polemics from the comfort and convenience of Greenwich Village, Wood thought that artists should actually live in other parts of the country. He himself preferred the Midwest and taught at the state college in Iowa City. In his 1935 statement “Revolt Against the City,” the painter rested his case for regionalism on the psycho-geography of American art.

The East Coast was in the thrall of “the colonial spirit . . . basically an imitative spirit,” he wrote. Culturally, it was fated to proceed along tracks laid down by Europe and to fail to grasp what was “new, original, and alive in the truly American spirit.”3 Therefore, artists living elsewhere in the United States could save themselves a lot of hassle and stay right where they were:

The artist no longer finds it necessary to migrate even to New York, or to seek out any great metropolis. No longer is it necessary for him to suffer the confusing cosmopolitanism, the noise, the too-intimate gregariousness of the large city. True, he may travel, he may observe, he may study in various environments . . . but this need be little more than incidental to an educative process that centers in his home region.4

Wood outlined a plan for the development of regional art centers through federally funded art schools, with annual regional exhibitions and collaborative public works to spread the joy of art to the people. He thought that a place should celebrate its local artists the way it did the high school football team.

The sentiment would surely pass muster with Sara Daleiden, a young Milwaukee artist and art-community advocate. We were in a bar. I ordered a Riverwest Stein, made by the nearby Lakefront Brewery, and Sara wondered aloud: “Could you get people to invest in local artists the way they invest in local beer? Look at what’s on tap: all these nuances of Wisconsin that you’re buying. I’m trying to translate that idea into art.”

John Riepenhoff showed up, and the two immediately fell into an animated discussion about art promotion. They sounded a bit like lobbyists for an under-recognized industry—the U.S. goat meat industry, perhaps, brainstorming how to get people to eat more goatburgers.

“I think there could be a shift toward wanting to consume regional ideas,” John ventured. After all, artists and audiences in a place experience the same seasons and navigate the same landscape as they go about their business. This, too, echoed a Grant Woodism: that the physical geography of place would invariably impress its unique characteristics on those most sensitive of seismic registers: its artists. I wondered what this meant for the artists of Milwaukee, situated between three rivers and subject to the massive weather generator of Lake Michigan. Is lake-effect precipitation conceptually encoded in their art?

Earlier that the evening, Sara had hosted a workshop on fundraising for artists in conjunction with a show she’d organized at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design. She walked her small audience through the steps of finding and applying for grants, writing convincing project proposals, and forming nonprofit organizations. Halfway through the talk I realized that Daleiden isn’t an artist who fundraises in order to make her art; fundraising pretty much is her art. She has turned her grant-writing practice into an artistic practice: a poetics of initiative building, cover letters, project narratives, fiscal accountability reportage, and budget summaries.

She called this “institutional mimicry” and considered it a handy tool for artists in a place like Milwaukee. You have to speak a language that people understand if you want them to take you seriously and give you money.

For example, Sara heads up the advisory board of a group dedicated to the preservation of a local public artwork called Blue Dress Park. The group also includes John, several community representatives, members of Milwaukee’s Municipal Land Use Center, and the artist Paul Druecke, who created the park. The board, the Friends of Blue Dress Park, had a meeting that weekend in Chicago.

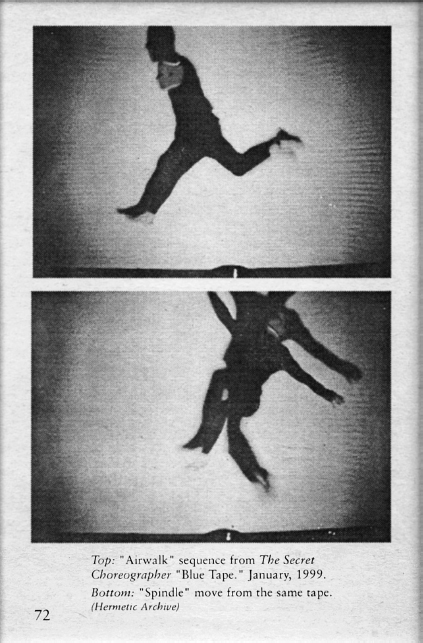

Blue Dress Park itself is a superfluous wedge of concrete on the dividing line between the neighborhoods of Riverwest and Brewers Hill, next to a bridge overlooking the parking lot of the Lakefront Brewery: a thickened sidewalk, really, about as big as a basketball court, a minor accident of urban planning made even more conspicuous through the addition of a knee-high iron railing along its perimeter. Druecke didn’t alter it in any way; he just decided it was a park, gave it a name, and sent out invitations to a christening party. Grant Wood might have endorsed the gesture as “a utilization of the materials of our own American scene,” had he been willing to consider an unadorned patch of city concrete a work of art.5

Blue Dress Park seemed like simplistic piece of art until I actually thought about it. As it is in most American cities, contemporary art in Milwaukee is intrinsically bound up with gentrification; judging by the tendency of exhibition spaces to spring up in disused industrial zones or low-income neighborhoods just before the cafes and clothing stores do, you could say that the current civic function of art is to kick-start the process. And gentrification is as much about names as actual changes to the urban landscape. As Druecke was beginning his project in 2000, residents of Brewers Hill were battling a proposed condo development. They worried that it would clash with the historical character of the neighborhood: the old beer barons’ mansions and Greek Revival and Italianate homes that the National Historic Register identifies as Brewers Hill’s architectural contribution to the country. In a further affront to the community, the name of the proposed development was Brewers Hill Commons.

But then again, the name Brewers Hill only really emerged in the 1980s. Before that, the area was more commonly considered the southern end of Harambee—a neighborhood that had come to be called Harambee a decade earlier, when some of the area’s African American residents adopted a Swahili word meaning “pulling together” as a rallying cry for grassroots urban renewal. The differentiation between Harambee and Brewers Hill occurred at about the same time that a new influx of residents—primarily white people who dug buying and renovating dilapidated historic houses—took an interest in the area and the demographics of the neighborhood shifted.

So Druecke’s act of designation, however wan, was just the most recent in a very long chain. It stretched all the way back to the Algonquian and Siouan peoples who’d lived in the area before waves of French Canadian traders, missionaries, and soldiers showed up, garbled a few of their place-names, and eventually ended up with the name Milwaukee. And in the context of present-day gentrification, naming something art has serious implications. I suspected that the slightness of Druecke’s intervention pointed to a certain scruple about this fact: a desire to tread the city with the lightest possible footprint.

On the tenth anniversary of the christening, the Friends of Blue Dress Park hosted a bratwurst cookout there. They covered the concrete wedge in red-and-white plastic gingham tablecloths, like a giant picnic blanket. Milwaukee’s lone art journalist, Mary Louise Schumacher of the Journal Sentinel, blogged about the event: “The crowd may have been modest, but a steady stream of Milwaukeeans showed up, umbrellas hoisted overhead, to have a nibble, catch up with art- and architecture-world chums and to support the inauguration of a new group that wants to create value in marginal spaces, in ill-advised bits of urban design.”6 The lesson here was that you can begin something as an art project and end up being a pillar of the community.

John had offered me a spare room in a two-story industrial building on the northeast corner of Riverwest that he uses to put up visiting artists. The building housed three artists who’d lost their spaces in the East Center Street fire. They had divided the garage space on the ground floor into studios and converted the office space upstairs into an apartment. Alec Regan and Brittany Ellenz, one half of the art collective American Fantasy Classics, directed me to a cornucopia of toiletries in the hall closet: bins full of individually wrapped bars of soap, cardboard boxes overflowing with toothbrushes and sample-size tubes of toothpaste, racks of shampoos, conditioners, and lotions, all donated after the fire.

By the 1960s, art in the United States was, charitably speaking, a two- or three-city game. Los Angeles and Chicago were in it, but only barely; New York had held the lead since the end of World War II. The Abstract Expressionists had put the city on the world stage, and it no longer followed developments in art unfolding abroad—many key European artists lived there, anyway, having fled to the States before or during the war. New York was the place where innovation happened, and it was only a matter of time before innovation got around to transforming the idea of place.

Following the progress of Abstract Expressionism (and its various painterly and sculptural offshoots) into something like American art’s house style, younger artists needed a new direction. Rather than attempting to progress within the categories of painting or sculpture, they turned their thoughts toward the categories themselves: Why so few? What else could an artwork be? Conceptual art, as one answer among many to that question, proposed a model of art-making that would have serious repercussions for the relationship between the artist and geographical space.

Ideas, as works of art, were inherently more portable than paintings or sculptures. And while paintings and sculptures did travel all the time (in fact, the CIA funded several touring exhibitions of Abstract Expressionist art in the 1950s, conceived as cold war demonstrations of American cultural values), ideas could zip through a host of distribution systems at a fraction of the time or cost.7

Conceptual art spokesman and dealer Seth Siegelaub pioneered new exhibition strategies for the work of artists he represented. He arranged shows that existed only as books, posters, or calendars; collections of statements, proposals, and drawings reproduced by Xerox copy; art actions that occurred at remote locations and were then publicized via mail. For an exhibition at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, he organized a symposium as a conference call between the audience in Burnaby and the artists in New York.

If Abstract Expressionism had been all about presence—standing directly in front of a painting where the artist had once stood and experiencing it—Conceptual art cultivated an equally strong aesthetic of distance. Artists in New York sent instructions to have sculptures constructed in Düsseldorf or Zurich or simply sent their concepts out into the informational ether via phone or fax. This mobility fostered faster exchanges between artists in different areas and a greater parallel processing of artistic ideas. By the standards of the digital revolution, it was all about as fast and efficient as the Pony Express. But Conceptual art went a long way toward shortening the lag time between the established centers of the avant-garde and emerging ones.

The next logical question was, if the art could be conceived in one place and manifested somewhere else, why were artists still hanging around SoHo? In 1969, Siegelaub felt that the information revolution had created conditions such that artists could live anywhere in the world, participating in the most up-to-the-minute dialogues in their field. “I think it’s now getting to the point where a man can live in Africa and make great art,” he remarked.8

In that sentence, man and Africa tell us something about the chauvinism and provincialism of the art world in late-1960s New York: what was counterfactual and speculative for Siegelaub is now commonplace, and art’s dialogues now include more participants in more places than were conceivable in 1969. The interesting thing, though, is how different his version of relocation is from Grant Wood’s. Rather than imagining the artist as a thinker of and through place, shunning the metropolis and creating for a local audience, Siegelaub, and the worldview of Conceptual art, envisioned her as something like a telecommuting worker.

David Robbins, Milwaukee’s resident media guru and former 1980s quasi–art star, is a staunch believer that the Siegelaubian moment has finally arrived—albeit forty-odd years after the fact. “When I moved to New York in 1979, a long-standing phase of culture and society was still in place where, if you wanted the New York information, you moved to New York,” he said. “Today I wouldn’t have to do that. Courtesy of the Internet, I have access to much of the same information a New Yorker has, and at exactly the same time. Do I have 100 percent of the New York information? No, I have 70 percent—but the remaining 30 percent is basically who sat next to who at dinner.”

We sat in the front room of his house, the window of which would have looked out onto a placid residential street in Shorewood, the closest of the city’s string of northerly suburbs—except that the blinds were drawn tightly shut to keep the glare off the enormous monitor of the desktop computer where he makes his art. A digital video camera on a tripod pointed up at the ceiling, and the closet was overfull with the empty boxes and foam packing forms of video and audio components.

When Robbins did move to New York, he fell in step with a generation of artists crossbreeding entertainment strategies with Conceptual art. He worked for Andy Warhol for a while. Robbins’s most famous piece of art is a work from 1986 called Talent: eighteen framed black-and-white publicity shots of his downtown cohort, including fresh-faced ingénues like Cindy Sherman and Jeff Koons. He returned to Wisconsin when his parents fell ill, and stayed.

Robbins doesn’t teach in the city, and he professes no interest in influencing the course of its visual art. Nevertheless, he hovers quite conspicuously behind the scenes. The art discourse of Milwaukee, and the work of its young artists, are both deeply Robbinsian. For example, I heard the words platform, platforming, and even the unusual platformist from at least six different people during my three days in Milwaukee. I wondered why this bit of art-speak was so popular and eventually traced it back to Robbins’s 2009 book High Entertainment, which provides a kind of blueprint for the cross-promotional art practices I’d observed—John’s “Art Stands” and the public art advocacy of the Friends of Blue Dress Park:

A platform is a context, medium, or venue for the presentation of people, events, objects, or information . . . The one who innovates the platform and works actively with it as a medium for the presentation of others is a “platformist.” The platformist is a kind of artist—an artist at presenting others.

Robbins is supportive of Milwaukee’s younger artists but somewhat skeptical that contemporary art should be the ultimate goal of everything. Lately, he’s taken to making quirky online advertisements for things he likes, such as the work of other artists or abstract values like beauty. He encourages his unofficial protégés to look outside the category of art for new things to do; this, paradoxically, is what artists are supposed to do anyway.

I got the impression that any sense of alienation Robbins felt living here was balanced by the satisfaction he took in being a unique feature in its cultural landscape. Walking outside his house to say goodbye, he gestured at the nice cars and manicured lawns of the houses next to his and told me, gleefully, that not one of the other people living on his block was an artist.

For other local artists, life as a displaced avant-gardist is a less comfortable fit. The performance artist and videographer Kim Miller talked about the challenges of working in nontraditional media in a city where, for much of the population, art still means painting or sculpture.

“I grew up here and got out,” she said. Miller attended Cooper Union in New York and then worked with an all-women performance art group, since disbanded. Like Robbins, Miller returned to Milwaukee when her father got sick, and she now teaches in both of the city’s college-level art programs. She and her sister live in a stately, narrow two-story home on a wide, tree-lined street. “It’s a nice reason to be here,” she said.

Her daughter, Lillie, poked her head through the door and observed us. Miller suggested we watch some of her videos in the kitchen. “And then”—looking at Lillie—“we can watch Pirates of the Caribbean.”

We watched Quincy Jones Experience, a piece from 2008. In the video, Miller is behind the wheel of a car holding a microphone; a slice of silvery-green suburbia scrolls past outside the window. She says that she’s been “going through some things” and that she has discovered a new coping mechanism. She tells a rambling story about Quincy Jones and the nervous breakdown the musician suffered after the success of Michael Jackson’s Thriller in 1982, his unsuccessful attempts to recuperate at Marlon Brando’s estate in Tahiti, and his eventual discovery that the sleep-aid drug Halcyon was responsible for his paranoia and hallucinations. The coping mechanism that Miller’s character has discovered is never identified, other than that it “has to do with the simultaneous acknowledgment of the front and back of the head.”

In the next video, Miller is pulling a pair of tan pantyhose over her head, bank robber style, and then pulling them off again. With the hose on, she threatens the viewer: “Don’t say a fucking word” and “Deal with it, cocksucker.” When she takes them off, she smiles and issues platitudes: “It’s all about choices. You’re in control” and “You’re doing great.”

I told Miller about an art opening I’d been to the night before. “I think—don’t be offended—that it’s easy to come from outside and romanticize something,” she said. “It’s a very specific scene and has a very specific demographic. This is a very diverse city . . . Friends of mine that are not white don’t want to go to things like that. Maybe that’s not just specific to Milwaukee.”

And then, “Sorry, I feel like I’m bumming out on this! Because it’s such a small scene, it’s also so hard to say this, because you’re probably seen as disrespecting a few people and their really hard work. They work twenty-four hours a day on these things. Someone like John Riepenhoff is a really hard worker, and I totally respect that.”

Fredrick Layton, an English American meatpacker, built a public art gallery in 1888 to display his recently acquired collection of European and American paintings. He put an art school in the basement. This got the ball rolling for art appreciation in Milwaukee.

The Layton Gallery eventually grew into the Milwaukee Art Museum, which over the years has received major gifts from benefactors of many stripes: Richard and Erna Flagg, a tanner and his wife originally from Frankfurt, Germany (Renaissance, Medieval, and Haitian art); René von Schleinitz, the secretary of a large mining equipment company (19th-century German and Austrian painting and decorative arts); Maurice and Esther Leah Ritz, an accountant and the first female president of the Milwaukee Jewish Federation (German Expressionist art); Anthony Petullo, a retired Milwaukee businessman (outsider and self-taught art from America and Europe); and Mrs. Harry L. Bradley, wife of a factory automation magnate and cofounder of his right-wing philanthropic foundation (European and American paintings, prints, watercolors, and sculpture, late nineteenth century to the early 1970s).

The museum struck me as somewhat detached from the city’s local art production—but no more so than most regional museums, even those devoted exclusively to contemporary art. Its contemporary programming is primarily drawn from the same traveling pool of prominent figures whose work graces the walls of comparable institutions from San Diego to Boston. By and large, local art is the domain of educational initiatives and juried exhibitions.

The relative absence of an art infrastructure in Milwaukee means that artists can play a bigger role in determining how things are going to go; in this respect, the scene is wide open to change in a way that places like New York, or even Chicago, haven’t been for generations. But a lack of relevant institutions also means a lack of institutional memory: details fall through the cracks, and it comes down to the artists themselves to perform the archival work usually managed by museums and the more dedicated private collectors. Art history is a DIY operation.

Nicholas Frank, another organizer of the Milwaukee International Art Fair, ran a gallery called the Hermetic from 1993 to 2001. During that time, he witnessed the coalescence and disintegration of a vibrant art scene around UWM’s experimental film program and the artists it brought to town—a recent Golden Age that already seems like ancient history, complete with a register of now-defunct art and performance venues: Metropolitan, The General Store, Jody Monroe Gallery, Hotcakes, the Bamboo Theater, Pumpkin World, Rust Spot, Darling Hall. Frank, David Robbins, and a filmmaker named Jennifer Montgomery began work on a documentary about it, called The Milwaukee Moment, just as the scene started to break apart.

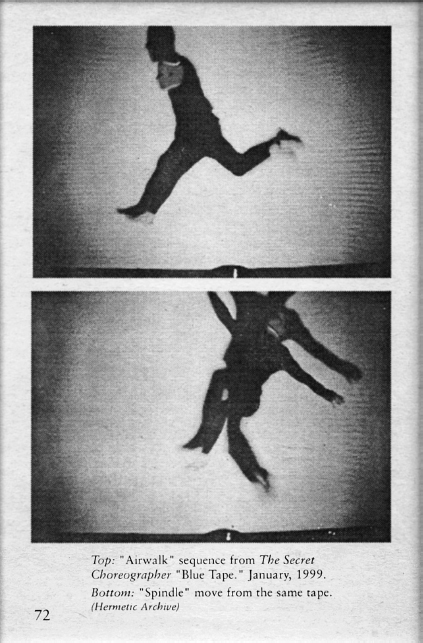

Since then, Nicholas has embraced more skewed forms of documentation. Sitting in his kitchen in Riverwest, he showed me framed book pages from a project called The Nicholas Frank Biography. In reverent, inflated prose, the biography details key moments from his artistic career, some based on real events and others manufactured as fodder for the project. “Frank’s subsequent campaign to export a case of New Milwaukee beer into outer space failed, of course, due to the ridiculousness of the proposition,” reads one excerpt. Another tells the story of the Secret Choreographer, an anonymous guerrilla artist (Frank, dressed in a balaclava and leotard) who breaks into galleries after hours to dance around other artists’ work.

The project is exuberant, inspired, and utterly grim in its predictions about the eventual fate of art made in peripheral places. “I did this because at one point I was sitting in my studio, totally abject about the fact that I live in Milwaukee and that I have great ambitions, but I will never be recognized as an artist in any substantial capacity,” he said. “I thought, ‘This is beyond my reach, so I’m going to make it myself. I’m going to preempt posterity.’”

Frank asked if I’d like to see the studio. We got up from the table, walked about eight feet to the back of the kitchen, and stood in front of a door. He reached into a cardboard box and held out what I thought were two plastic sandwich bags.

“I want to give you the opportunity to fully explore,” he said. “So it’s standard operating procedure to put these booties on.”

My shoes protected, Frank opened the door on a room about the size of a generous hotel bathroom. The floor was covered wall-to-wall with wooden panels wrapped in paint-smeared and footprinted canvas, which fit snugly next to one another like tatami mats. On top of these were a bunch of fifteen-by-sixteen-inch canvases, open tubes of paint, thinner-soaked rags, and brushes. He explained that the floor was both a palette for the small paintings and a painting itself.

For Frank, an artist’s studio is a narrative space. The ultimate artistic localism is the localism of the studio. The studio is a continuum in which the products of artistic work are completely present and alive—unlike the dim phantoms of themselves they become when you take them out of the studio and exhibit them, or read about them and see their pictures in an art magazine. “When you pull the objects out, you kind of fuck with the program,” he said. “Like history does. History is an oversimplification of activity.”

Appropriately, the most prominent benefactor of Milwaukee’s artist-organized contemporary art scene was neither a beer baron nor an industrialist, but instead a reclusive sculptor who lived in the suburbs. Over her lifetime, Mary Nohl transformed her family’s former summer cottage in Fox Point into what German avant-gardist Kurt Schwitters would have recognized as a Merzbau and Soviet-born Conceptualist Ilya Kabakov would call a “Total Installation”: a complete artistic environment incorporating her concrete and driftwood sculptures, paintings, ceramics, murals, jewelry, found objects, and prints into a living work of art.

The neighbors, however, hated it; Nohl was subject to a lot of local harassment during her life. Her sculptures were vandalized or set on fire, and her cottage was known in Fox Point as “the Witch’s House.” People were fond of shooting out its windows. Despite this treatment, Nohl, the eccentric daughter of a prominent Milwaukee family, left $9.6 million dollars to the Greater Milwaukee Foundation after her death in 2001.

This money endowed the Nohl Fellowship, awarded yearly to emerging and established artists from the area. The emerging artists get five thousand dollars and the established ones fifteen thousand. Polly Morris, a former dance company organizer, oversees the selection of grant recipients through the Bradley Family Foundation. “Inevitably over time you come to know a ton of artists, young and old, many of whom hate you when you do something like this,” she told me.

In 2011, American Fantasy Classics, my hosts in the loft in Riverwest, received the fellowship as a collaborative entity. They funneled the entire purse into an ambitious installation for the show at the Institute of Visual Arts celebrating the grant winners. (“We spent the last dollar on the day of the opening,” Alec said.)

Their piece, The Streets of New Milwaukee, was a life-size, walk-in diorama of a seedy-looking city block. Viewers strolled down a central aisle floored with concrete squares and terminating in a chain-link fence at one end of the gallery. Ramshackle storefronts and stalls, painted to look like graffitied brickwork or stone, lined the darkened room. Rickety signs promised dubious entertainments: Video Club, Waffle Plaza. I opened a door beneath a neon sign reading DUNK onto a tiny brick-walled room with a microphone stand in it. Windows revealed artfully dingy cubicles crammed with bits of street detritus, and an illuminated billboard displayed ads for cell phones.

The installation riffed on a beloved local attraction: the Streets of Old Milwaukee, a diorama at the Milwaukee Public Museum replicating a turn-of-the-century cityscape: cobbled streets and gas lamps, an apothecary’s shop, and a brew pub complete with a mustachioed mannequin bartender in sleeve garters. The look of AFC’s version was modeled on the background from Streets of Rage, a scrolling martial arts videogame from the mid-1990s.

I didn’t get the name American Fantasy Classics until I looked at a Milwaukee online Yellow Pages and saw listings for businesses like Absolute Custom Extrusions, Glam Star Industries, and American Muscle Car Gearheads. The group, which assembled a few years ago when its four members were undergrads at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design, operates like an autonomous team of studio assistants: they invite an artist to do a project and then put themselves to work in realizing it. They collaborated with Portland, Oregon, digital artist Brenna Murphy to convert the psychedelic abstract forms and organic textures of her website into a low-fi floor sculpture, ludicrously made out of painted wooden polygons, gourds, sand, rocks, ceramic vases, cast fried eggs, and jalapeño peppers.

During my visit, the group was in a transitory state. Alec and Brittany would continue to operate in Milwaukee, but the other half of AFC was headed south: Liza Pflughoft had already moved down to Texas for graduate school, and her boyfriend, Oliver Sweet, planned to join her. I asked them if they anticipated any problems collaborating over such a long distance, and they laughed. Most of the time they never even meet the artists they work with—the project usually happens over e-mail. So why would it matter that they’ll be living in different cities?

In 1996, French critic Nicolas Bourriaud looked at a collection of art practices that had emerged in the nineties but harkened back to the art of the sixties. These forms riffed on the participatory qualities of performance art, the prankish multimedia experimentalism of the Fluxus movement, and Conceptualism’s emphasis on ideas over materials. New York–based Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija set up a makeshift kitchen in a gallery and prepared meals for viewers. Visitors to a show by Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster could make an appointment to have their life story recorded by the artist. Maurizio Cattelan made an elaborate costume for his Paris dealer, resembling something between a pink rabbit and a giant furry penis, and challenged him to go about his business for the duration of the exhibition while wearing it.

Bourriaud homed in on the common element in these types of projects and their philosophical core: they all focused on the social space in which our encounters with art take place. He coined the term Relational Aesthetics to describe the way these artists emphasized dynamic interpersonal exchange over the solitary contemplation of art objects. “Artistic practice appears these days to be a rich loam for social experiments, like a space partly protected from the uniformity of behavioral patterns,” he observed—perhaps the antidote to consumer culture’s programmed numbness was through contemporary art.

Relational Aesthetics was part of a period in art and culture obsessed with motion and the pressures of globalization. In an extension of the Conceptualist model, the artist—not the work of art—moved from place to place, interfacing with curators and institutions and making things happen on an international circuit of biennials, triennials, and art festivals. (Briefly, Milwaukee itself constituted a minor stop on this busy circuit: a curator at the Institute of Visual Art named Peter Doroshenko invited many Bourriaud luminaries to stop in and make shows there.) The form bloomed in the pre-9/11 golden age of hassle-free commercial air travel and thoroughly tweaked the traditional models of centers and margins in art: the artist could be anywhere, provided she never stopped moving.

Later, Bourriaud evolved these ideas into a manifesto of sorts, which he titled “The Altermodern” and published on the occasion of the Triennial at Tate Britain in 2009. Travel, real and metaphorical, abounded in his text. “Our daily lives consist of journeys in a chaotic and teeming universe,” he wrote, and compared the artist to the pilgrim, “the prototype of the contemporary traveller whose passage through signs and formats refers to a contemporary experience of mobility, travel and transpassing.”9

This somewhat glamorous aesthetic of perpetual motion is nearly inverse to that of the present-day Milwaukee scene, where travel is more likely to mean red-eyes and couch-surfing than international flight and hotels comped by museums; less about maintaining a presence on a global art circuit than about moving back home to take care of your parents. Nevertheless, the Relational Aesthetics flavor is present in the work and ideas of many of the city’s artists. No one cited it to me as an explicit point of reference, though it was clear that other spectators have made the connection. “We didn’t know anything about that as we were building our scene here . . . We were entertained by that framing of things,” Riepenhoff told me, recalling all the times he’d gotten an earful about Bourriaud and his theories.

That night, American Fantasy Classics was gearing up for a recently inaugurated Halloween tradition called the Ghost Show: a one-night exhibition, costume party, and concert held in several Riverwest art spaces. This would be the third Ghost Show—technically, it would be 00000 Ghost $how III, as the exhibition was billed on its flyers and Facebook event page. The Reeders were up from Chicago and would be performing in a band.

John arrived at the loft, and we went to pick up his cousin and business partner, Jake Palmert, who had just arrived from New York, where he works as the director of a gallery on the Lower East Side. Since downtown New York was still dark, and largely wet, he’d decided to head back to Milwaukee for the weekend. We drove over to Imagination Giants, a ground-floor exhibition space on a residential block in Riverwest.

The main gallery was dimly lit, as befitting the occult theme of 00000 Ghost $how III. A gorilla mask mounted on a tripod faced out the front window, and the rest of the room was sparsely hung with spooky artworks: a red cloth mask pinned to the wall next to an ominous photograph of a house, a TV monitor playing jittery footage of Glenn Beck. Down a narrow flight of stairs, a basement with wooden palettes piled into a corner housed a few more monitors and photographs.

Most of the costumed crowd was gathered in the darkened rear gallery on the first floor, where the Ghosts were performing fuzzy psych-rock numbers behind a floor sculpture of a pentagram. True to their name, the band was garbed in white sheets with big cut-out eyeholes; one Ghost crouched behind a sampler and triggered haunted-house sound effects. A light machine threw oscillating patterns of stars onto the walls of the room. During their finale, some of the Ghosts rushed out of the room under cover of a fog machine and magically reappeared outside the window in the back of the room, waving.

I met Tim Stoelting, one of the proprietors of Imagination Giants. A thin guy in a tinfoil hat and a gas station attendant’s shirt, Tim was telling John about a new drug called krokodil, an easily manufactured but deadly opioid currently decimating the addict population of Russia. “It eats your skin,” he said.

“Is it called ‘crocodile’ in English or Russian?” asked John.

I thought about Kim Miller’s gentle critique of the insularity of the Milwaukee scene. John and Jake of the Green Gallery, the Reeders and their circle, and the younger network of student-gallerists doing the Ghost Show formed a close-knit network. Despite the fact that they seemed like nice people—nice guys, for the most part—they had their own set of preferences, prohibitions, and assumptions. These reinforced modes of behavior and art production that you had to adopt if you wanted to be in the group. However inclusive they intended to be, if you didn’t like their brand of jokes, or didn’t think that art and jokes should even remotely go together, then the city could probably be a small place indeed.

John and I left and walked halfway down the block to the smallest of the Ghost Show’s exhibition sites, and a perfect icon of the city’s signature, deadpan riff on post-globalization contemporary art: 516-TJK, a “mobile project space” in the guise of a 1996 Honda Accord. Julio Cordova, its owner and proprietor, was dressed in a black hoodie and black-and-white skeleton makeup. He popped the trunk to reveal a sculpture by an artist named Carly Huibregtse: a crumpled digital print on vinyl of a magazine-collage after Jan van Eyck’s Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, from the famed Ghent Altarpiece.

If contemporary art in America finally does decentralize and move toward something like localism, the reason may not be ideological, conceptual, or critical. It may simply be a result of fatigue. The populations of working artists in the big market centers are stretched historically thin; they can hardly be said to exist in the center at all. With the exception of a statistical handful blessed either with commercial success or independent wealth, they work freelance but full-time. They commute for hours and hours every week to teach in faraway cities, and sleep on the floors of their offices there. They pay high rents on studios that may as well be in other time zones than the galleries and museums they want to visit. They have just about enough time left over from making a living to make art, but not quite enough time to see anybody else’s art. Don’t pity them, necessarily, but understand their situation.

Meanwhile, art-making on the national scale is a picture of uncontainable growth: microworlds of contemporary art bubbling up everywhere, with near-infinite variations and repetitions, responding to conditions on the ground in places as different as Dallas and New Orleans, Portland and Phoenix. Even the market centers of Los Angeles and New York contain smaller art communities so distinct, autonomous, and developed as to constitute localities in their own right. Some of these are miniature reproductions of the high-end art world, replicating its priorities, hierarchies, and exclusions. Others are significant, imaginative deviations from the model.

The only problem is that the bulk of this activity fails to register in the organs of mainstream art media, or in the art market. A huge portion of it is ephemeral, waxing and waning according to changes in the general economy, cycles of the academic calendar, or phases in the evolution of a city, and leaving little in the way of documentation once it passes on.

For many people invested in the art industry—either professionally, as a career, or literally, in the sense of buying the stuff—the idea of treating art as a local product is a profoundly foreign concept. In order to acquire value, a piece of contemporary art is extracted from its initial context—the creative community whose collective work makes any individual’s work possible in the first place—and circulated through the giant legitimatization system known in shorthand as the international art world.10 Thus no matter where it’s made, exhibited, sold, and bought, contemporary art is conceived as an import good. Proposing that we approach it like a case of microbrewed beer or a loaf of bread may have significant consequences on its pricing, for starters—but it may also offer a new perspective on the value of art.

Paradoxically, localism in art would first mean a reckoning with the true scale of contemporary art production in the country: that there’s more of it by an order of magnitude than can be shown in galleries or art centers, interpreted in magazines or on websites, curated into regional, national, or international survey exhibitions, bought by collectors or acquired by museums, or recorded in art histories. Taking this condition seriously, as an essential quality of contemporary art (rather than a distraction that history will eventually eliminate), would require new methods of analysis; new journalistic, critical, and historical strategies; and most of all, new modes of appreciation. What kind of art would be as indispensable to everyday life as beer or bread?

Art localism would also mean ditching the fantasies of stasis and flight that have animated discussions about space in American art since the 1930s. What’s needed is a more accurate model of the contingent allegiances to place, and erratic forms of motion, particular to most artists these days: everyone has to be somewhere, even if there’s no good reason for it, and even if their work happens elsewhere—and no one stays anywhere for long.

On the night I left Milwaukee, Alec, Brittany, and Oliver were sitting around the kitchen table of the loft planning an American Fantasy Classics event at the Institute of Visual Arts next Thursday. On specified evenings, The Streets of New Milwaukee housed Nightlife, a mini-festival with a variety of entertainments: seminars in a tiny classroom given by a local artist named Rudy Medina, concerts by a local retro-1950s rock band called Chubby Pecker, and, in homage to the Reeder’s legendary Club Nutz, stand-up comedy in the closet-size nightclub called DUNK.

The centerpiece of Nightlife was supposed to be a ramen shop manned by none other than local arts impresario John Riepenhoff—but two weeks earlier, on the afternoon of the opening, the director told them they weren’t legally allowed to serve food to anyone in the gallery. This time, they had decided to serve tea instead.

They still needed to fill one spot in the lineup, though. Alec had just learned that Medina, their seminar instructor, wouldn’t be able to participate. “I talked to him two weeks ago and asked if he had anything planned for this next event,” said Alec. “I said it would be cool if he did something more participatory—last time he just played these cell phone videos. And he was like, ‘Yeah, that’d be good, for sure.’ And then I found out three days ago that he moved to Mexico City.”