Pamela Parmal

Department Head and David and Roberta Logie Curator of Textile and Fashion Arts

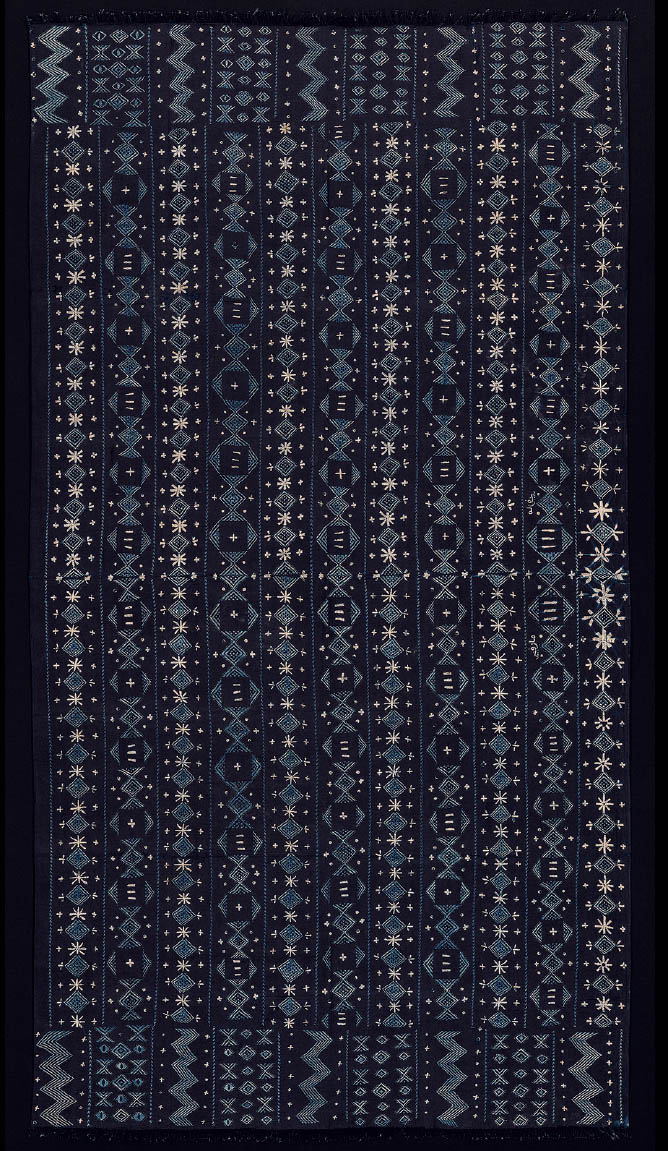

INDIAN Cotton Textile Fragments, in Two Pieces, probably 14th century

INDIGO BLUE, THE COLOR OF DENIM and the night sky, can be found in clear translucent tones or can appear inky black. The indigoid dye comes from a variety of plants that are grown throughout the world. It is extracted through fermentation and then dried into cakes that can be more easily shipped and traded. In Europe and colder climates, indigo was extracted from the leaves of a flowering plant called woad (Isatis tinctoria). In more tropical climates, the plant Indigofera tinctoria, true indigo, produces a more concentrated, more easily processed dye. Indigo cultivation and processing probably developed in India, and trade was established with Asia and the Mediterranean world by the second millennium BC. The earliest dated indigo-dyed textiles have been found in Egypt. Tutankhamun owned a blue state robe, and other similarly colored textiles were found in his burial chamber. In Egypt, blue was synonymous with the sky, the heavens, and creation, as well as the life-giving waters of the Nile. As such, it claimed an important symbolic role among the pharaohs (see page 61).

The process of indigo dyeing has its own magic. It occurs through oxidation. Cloth is dipped in a vat of the prepared indigo dye, and the color only becomes visible when the cloth is pulled out and exposed to the oxygen in the air. The cloth magically turns blue in front of your eyes: In the vat water, the cloth is dark blue-green, and then the cloth comes out a pale green-brown and begins to turn blue! The more often it is dipped in the vat, the darker the color. This characteristic of indigo dyeing has been exploited to create a range of blue from light to almost black. The process of vat dyeing makes printing with indigo nearly impossible, and different techniques have been developed to pattern cloth. The majority of these methods involve preventing the dye from penetrating selected areas of the textile or yarn by tying, binding, or covering with a paste. These resist-dyeing techniques developed in Japan, India, Indonesia, and Africa, where indigo dye was available in quantity.

The process of patterning cloth with indigo dye was perfected in India. With the concurrent developments in the use of mordant dyeing with the roots of madder, a perennial climbing plant, to pattern textiles in a range of reds, purples, and browns, the Indians created a major industry and began to export patterned cottons throughout the world. Their cottons were known in the Greco-Roman world, where they reached the Mediterranean through the Arab sea trade into Africa. Thousands of small textile fragments were found in the city of Fustat (Old Cairo) and other archaeological sites dating from the eleventh through the fifteenth centuries (see page 59). The fragments show a range of patterns and colors, indicating that the Indians had developed techniques and a sophisticated market, offering patterned cottons in a wide range of styles and price points.

As indigo cultivation spread throughout the world, different cultures adapted it to suit their own tastes. The Japanese probably developed the greatest range of patterning methods. Indigo dyeing was used to pattern fabric made into clothing worn by people of all social classes. Hemp and cotton textiles were patterned using ikat, tie-dye (see page 167), and a paste-resist technique called tsutsugaki, while the wealthy urban merchants wore sophisticated summer kimonos made of cloth on which the color had been hand-painted, then covered with a resist paste before being immersed in indigo (see page 68).

EGYPTIAN Fingerless Glove, 1550–1070 BC

ITALIAN Velvet with Design of Large Palmettes, 15th century

AFRICAN Wrapper, late 19th to early 20th century

BROMLEY HALL PRINT WORKS, ENGLAND Furnishing Panel: Chinese Figures, after 1774

INDONESIAN Man’s Lower Body Wrapper (Kain), early 20th century

West African indigo dyers also developed sophisticated patterning techniques. In Nigeria, adire cloth is patterned by tie-dye, stitch-resist (see page 55), and by hand-painting or block printing a starch resist. Senegalese dyers used the stitch-resist technique, in which sections of the cloth are bound tightly together and held with stitches, to create intricate patterns on deep blue wrappers (see page 61).

In Europe and other areas with colder climates, the processing of indigo derived from woad was difficult to do, and the yield was low. Indigo plants from tropical climates of India and Africa yielded far more dye, and processed indigo cakes were more easily shipped than the plants. When Europeans began the sea trade to Southeast Asia in the sixteenth century, indigo became one of its most valuable commodities and threatened the woad trade. The Portuguese, Dutch, and then English traders all imported vast amounts of indigo into Europe. In fact, more indigo was imported into Europe than pepper and the rest of the highly treasured spices. Indigo imports from Southeast Asia diminished by the late seventeenth century, when Europeans began to develop indigo plantations in the West Indies and in North and South America. North Carolina became one of Britain’s most important suppliers of the dye. In fact, the first African slaves brought to the Americas used their knowledge of indigo cultivation.

Indigo eventually supplanted woad in Europe and was used in the silk trade (see pages 61 and 97), as well as the developing printed textile industry (see page 62). It remained the most important blue dye until the end of the nineteenth century. It was, in fact, the dye chosen by Levi Strauss to color his denim jeans, first produced in 1873. A synthetic version of indigo was finally invented in 1897 by the German chemist Adolf von Baeyer for Badische Anilin und Soda Fabrik (BASF). Natural indigo and synthetic indigo were both used during the first half of the twentieth century until new artificial blue colors began to supplant them in the marketplace. The post–World War II period, however, saw a renewed interest in indigo dye, as the craze for blue jeans grew. No other blue dye could successfully achieve the worn, faded look so coveted by lovers of denim.

EGYPTIAN Vessel Fragment with Flying Birds, 1991–1783 BC

KATSUSHIKA HOKUSAI Mishima Pass in Kai Province (Kōshū Mishima-goe), from the series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei), ca. 1830–31

CHINESE Large Plate with Blue-and-White Decoration of a Pair of Mandarin Ducks in a Lotus Pond (detail), mid-14th century

FRENCH Quintal Flower Vase, ca. 1740

JAPANESE Kimono (Katabira), first quarter of the 18th century

ITALIAN Cruet for Oil and Vinegar, 1575–87

NICHOLAS HILLIARD Portrait of a Lady, ca. 1590–95

UTAGAWA KUNIYOSHI Favorite Customs of the Present Day (Tōsei fūzoku kō) , 1830s

ROGIER VAN DER WEYDEN Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin, ca. 1435–1440