Chapter 10

Transitions, transitions, transitions

In this chapter we will explore:

When I was an undergraduate studying psychology, there was a huge focus on child development, but less on development throughout the lifespan. Developmental psychology tended to use stage theories, where children progress sequentially through phases that were very much set within defined age brackets. I remember at the time thinking that this can’t be totally accurate and that even if a child was outside of these ranges it didn’t mean there was something wrong with them or they were ‘delayed’, as surely we as humans vary quite a bit. Now, most of my colleagues would agree that stage theories are more guides than rigid milestones, although we are so used to using developmental benchmarks they can actually create a huge amount of anxiety. Parents in particular can become understandably preoccupied with milestones, but some kids simply exhibit certain signposts when they damn well please! This goes beyond childhood however, and in most cultures there is a common view that as adults we ‘should’ reach certain landmarks at particular times in our lives. If we haven’t crossed these invisible lines, this sense of ‘missing the mark’ can be a form of Tiny T in itself, as we look at others and believe they somehow have it all figured out. At this point, I’d like to introduce you to Freya, a lovely young woman who came to me on the cusp of her thirtieth birthday:

I know it’s silly but I’m finding the thought of turning 30 terrifying – I don’t feel like I’ve done anything at all by now, and I don’t even know what I should be doing, not with work, whether to stay in my relationship or anything. I don’t think I’ll ever be able to afford to buy a house, and without a stable home how can we even start to think about having babies? Everything, I mean everything, seems out of reach and when I try to talk about it with my family they just fob me off and say it will all work out – but how? I’m not even sure who I am, or supposed to be any more – it’s like I’m going backwards, as I knew when I started working, or at least I thought I knew, and now I just don’t know. I don’t know what I should be doing with myself, or my life – what should I do?

Of course, I couldn’t answer that for Freya, as it was she herself who had the solutions – we just need to lean into the AAA Approach to uncover them.

Whose Stage Is It Anyway?

I would say the most famous stage theories include Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Stages of Human Development and Daniel Levinson’s Seasons of a Man’s Life (see the table).76 Both theories saw adulthood as developing from the age of 18, with a number of defined stages of development including early adulthood, middle adulthood and late adulthood. Quite a bit of our sociological and psychological understanding of people has been based on these sorts of theories, but it’s worth considering for a moment the context in which such concepts were created. Erikson’s theory was published in 1950, and Levinson’s in 1978. If we think for a minute how life was in these decades – how gender roles played out, for example – we can start to see why perhaps we should take these now widely accepted stages with a pinch of salt. Also, even the title of Levinson’s theory is rather biased – a ‘Man’s Life’ – and reflects the fact that he and most psychologists, researchers and scientists based their conclusions on research carried out predominantly with cis male participants. Indeed, Levinson later conducted interviews with women and found some differences, unsurprisingly. However, as the aim of such models was to identify the common themes over the adult lifespan, they did by their nature plonk people into boxes and exclude the complexity and variety of human experience, as well as the influence of a person’s context.

Focus on Tiny T: Sex bias in scientific research

When Levinson published his theory, the title probably didn’t raise an eyebrow at all – until relatively recently the belief that women’s bodies (and minds for that matter) were rather too complex to study was widespread in scientific and medical research. It seems astonishing now, but the vast majority of ground-breaking research is based on male biology – in humans, animals and even cells.77 78 This undoubtedly spilled over into psychological research and theory formation, a problem that we’ve been aware of since the 1970s79 although many models of adult life transitions and development are very much still based upon these ideas, so it is worth us always bearing this and other demographic biases in mind.

Adult psychosocial development

Period of development |

Erikson’s psychosocial conflicts |

Levinson’s transition/crisis points |

Social and biological clock tensions |

Early adulthood (20–40 yrs) |

Intimacy vs isolation |

Early adult transition (17–22 yrs) |

Finish education; first job; search for partner |

Age 30 transition (28–33 yrs) |

Concern over partner and career choice; parenthood |

||

Middle adulthood (40–65 yrs) |

Generativity vs stagnation |

Midlife transition (40–45 yrs) |

Unrealised dreams in sharp focus, both family and career; perimenopause |

|

|

Age 50 transition (50–55 yrs) |

Empty nest; menopause; sandwich generation pressures |

Late adulthood (65 yrs–death) |

Ego integrity vs despair |

Late adulthood transition (60–65 yrs) |

Acceptance of life choices, retirement, forced or otherwise; health deterioration; grandparenthood |

Despite the biases, we can’t overlook that there were many valuable findings from this body of research and theorising – mainly that throughout life we move through various phases of development, and within these periods there are numerous transitions, often referred to as a ‘crisis’. If we compare Erikson’s and Levinson’s theories side by side, particularly the former’s psychosocial conflicts and the latter’s transition points, we can start to build a picture of how transitions relate to Tiny T. In general, it is not the transition per se that causes Tiny Ts, but rather Tiny Ts may make it much harder for people to work through a transitional crisis or psychosocial conflict in their lives. What Freya was describing certainly sounded like a crisis – a transitional crisis in fact – and we needed to do some work on the Awareness phase of the AAA Approach to discover if some Tiny Ts were making this journey more difficult for her.

‘I’m too young to feel this way!’ – The transitional crisis

Levinson’s theory clearly included an ‘age 30’ transition, sometimes referred to as a quarter-life crisis. But, of course, not everyone who approaches 30 will have a crisis, or it may happen later – we do, though, all experience transitions in our lives at various times. However, the main body of research on transitional crises has unsurprisingly focused on the ’mid-life crisis’ – a phrase that was first coined in 1957 by Canadian psychoanalyst and social scientist Dr Elliott Jaques, who observed middle-aged people (but mostly men) in his practice demonstrating the now classic mid-life crisis behaviours of trying to look young, buying a sports car and sleeping around in an effort to hold on to youth and avoid inevitable bodily decline and eventual death.80

But what was most interesting in Dr Jaques’ report was that people who hadn’t met their own and society’s expectations of life’s milestones seemed to experience this state of crisis more intensely than others and struggle with this transition to a greater extent than people who had neatly met all life’s sociocultural markers at specific timepoints. In other words, the question ‘How am I doing for my age?’ often rings in people’s ears as they look over at friends, loved ones and social media, and this also happens in early adulthood around the age of 30.

The social clock – a benchmark for comparison

We often talk about the biological clock when debating life’s milestones – well, child-bearing at least – but rarely the social clock.81 Like the biological clock, the social clock is a race against time, with age-checked social and cultural expectations for major life events such as securing your first job, being in a committed relationship or getting married, buying a home, moving up the career ladder and retiring, to name a few. The social clock appears to be a universal phenomenon, to the extent that a board game was made out of it! I had completely forgotten about The Game of Life by Hasbro until last Christmas when my niece and nephew wanted to play it – there are more than just blue and red play figures, but otherwise it hasn’t changed much at all. It is a spot-on demonstration of how pervasive the social clock is in many cultures. However, what you’d never be able to understand from this children’s board game is the way in which the social clock affects people, and how widely this can vary.82 Like so many things in psychology, if you believe it’s important then it will be so – but often when you look behind the curtain all is not as it appears.

If we look back at Freya’s narrative, there are lots of ‘shoulds’, ‘supposed tos’ and ‘sures’ – which are all forms of all-or-nothing thinking (Chapter 4). But this way of conceptualising our lifepath is not some miscalculation on Freya’s part; it is the type of Tiny T that stems from living in an environment that supports the notion of a social clock. To help Freya peek behind this sociocultural Tiny T curtain we started her AAA Approach journey with an exercise that enabled her to take a bird’s-eye view of her life course to date.

AAA Approach Step 1: Awareness

Exercise: Life-mapping

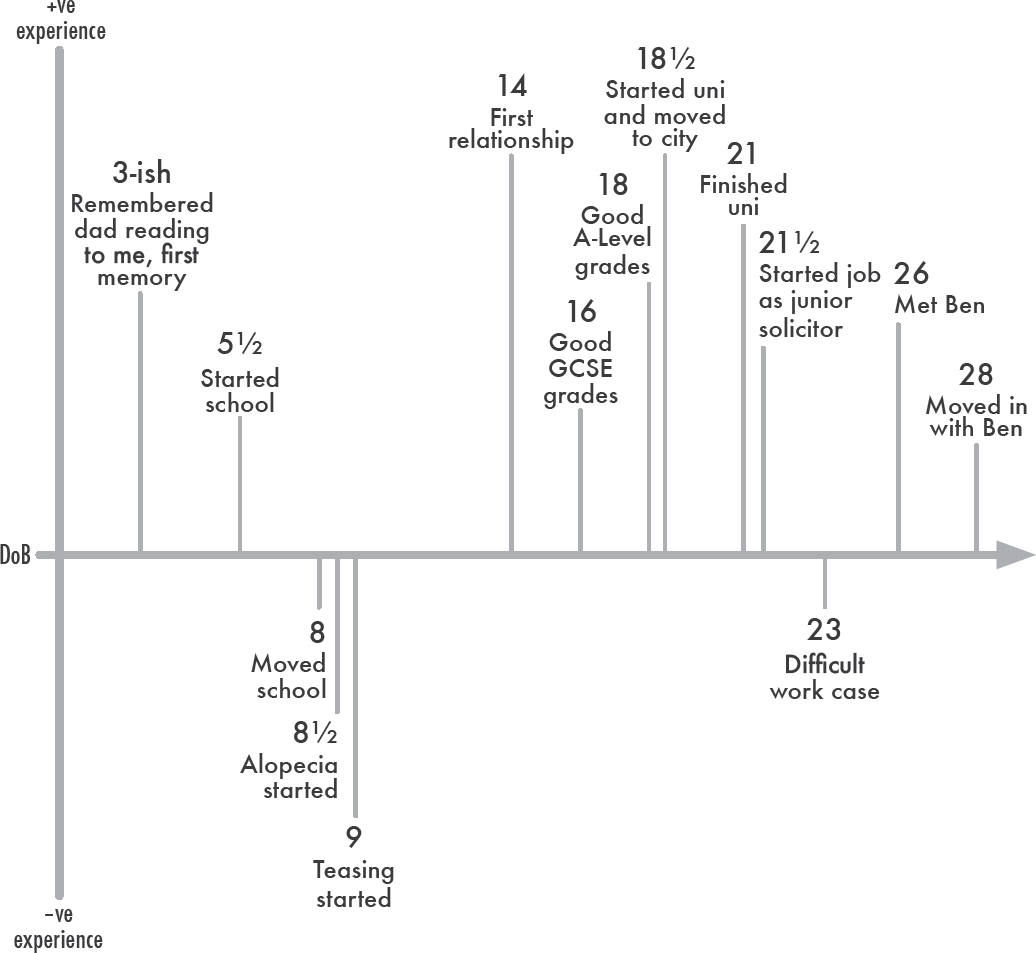

I often use a life-mapping technique with clients such as Freya who are at a crossroads in their lives, as it’s helpful to zoom out to increase Awareness. We grabbed a blank sheet of paper and placed Freya’s date of birth on the left-hand side of a straight line, like this:

Then I asked Freya to think about her experiences and jot these on her life-map – you can do this too by noting down:

- milestones or events that have been significant to you – not worrying about societal conventions of what should have been achieved by certain dates;

- achievements or realisations that you’re proud of, or have changed you in some important way.

- plot the positive events on the top half of the life-map, and more negative ones below. The height of each line should reflect how much the event affected you so that you can start to see what’s been most transformative in your life (both the good and the not-so-fun). You can also add the age it occurred to get a clearer picture of your chronology.

For each of these, it’s useful to write a few words of phrases as a descriptor.

Next, consider these probing questions to help you uncover more detail in this Awareness phase of the AAA Approach:

- What obstacles did you overcome during your journey? How?

- What did you discover about yourself during both the highs and lows?

- Can you see any common or frequently occurring values on your life-map?

Now, take a step back and take an overview of your life-map, but look at the map as if it belongs to someone else. How do you feel about this person when looking at their life-map from afar?

From looking at Freya’s life-map, both her Tiny Ts and some major life events came into focus. If you remember in Chapter 1, we briefly touched on the difference between Tiny Ts and life events – the latter being more obvious and notable experiences that most people would recognise as being challenging and/or transformative. Freya had already gone through quite a few of these – change in school, starting/finishing school/college/university, outstanding personal achievement, moving house – and they did indeed have an impact on her. But it was the Tiny Ts that we were more interested in and a couple of these more subtle nicks and cuts jumped out at me – one in particular was Freya’s difficult case at work.

A Child in an Adult’s World

Freya was a junior solicitor, specialising in family law, when she was asked to help with an acrimonious divorce involving two children. She was well aware that any type of split in assets can get a bit ugly, but she said she wasn’t prepared for how vicious this case turned out to be. Freya’s client was ‘using every trick in the book’ to get the settlement she wanted, and Freya said it was at this point that a hefty doubt about her lifepath started to rear its head. She had studied hard and was now in significant student-loan debt – Freya knew that she earned pretty well for her age, but it started to feel like it was at a high cost to her moral compass. She mentioned that she felt like a little girl at this time – supposedly an adult but utterly helpless in the situation, because as a junior solicitor she had no choice but to work on the case or potentially lose her job, career and never be able to find the financial security she required to start a family of her own.

Focus on Tiny T: Moral injury

The concept of moral injury originally emerged from situations such as armed combat and emergency medical cases, where someone witnesses, fails to act or even carries out something that goes against their core moral values and beliefs.83 There were many reports of moral injury doing the Covid-19 pandemic from healthcare workers who had to ration treatment that impacted on the survival of some severely ill patients, going against their oath of ‘do no harm’ for all patients. Yet moral injury can occur in anyone, in any setting, where there is injustice, perceived cruelty, degradation of one’s status or any other breach of a valued moral code. The Tiny T that forms is one that often starts with bewilderment, then morphs into resentment towards others, and the pairing of guilt and shame towards oneself. Like all Tiny Ts, if this was to happen in a war zone, we’d be able to spot it much more readily – but when a subtle moral injury occurs such as Freya’s case, people find it hard to discuss and come to terms with.

My fellow coaching psychologist Sheila Panchal has carried out some illuminating research into the ‘turning-30’ or quarter-life transition, which found that Freya’s review of her career trajectory was not uncommon at this point in life.84 85 Having invested both significant time, and these days money, into that trajectory, realising that it was not all it was cracked up to be was challenging. Along with this, there is an urge to supercharge salary and status to move up a level – which appears even stronger in times of high costs of living. The heady days of late teens and twenties hedonism tends to fade, as people approaching their thirties start to lose the assumption that they’re physically invincible and can get away with burning the candle at both ends. Indeed, I would say that at this point in history, the turning-30 crisis is experienced as particularly daunting.

For Freya, the moral injury she experienced also made her question her career choice, and to an extent her relationship. If we look at the table again, we can think about both of these internal battles as the conflict between intimacy and isolation. At some point in our lives – it may be when we’re around 30 but may be earlier or later – there is emotional and psychological tension between the need for closeness and the desire to be independent. It’s evident that Freya’s experience at work made her feel isolated when she needed support, yet she did want to appear that she was coping independently. This tension left Freya with a feeling of floating in space, untethered and confused.

AAA Approach Step 2: Acceptance

To move on to the Acceptance phase of the AAA Approach when it comes to Tiny T Transitions, it’s helpful to pause a moment and contemplate this space that Freya found herself in.

Liminal space

‘Liminal space’, or liminality, is the in betwixt and in between, wherein we can get rather stuck.86 This ‘stuckiness’ feels uncomfortable and is characterised by a sense of confusion, ambiguity and lack of understanding – as Freya revealed in our first meeting. It’s a bit like the ground falling away beneath your feet and you observing it, caught in the moment – what was known about the self, social roles and structures is questioned and often agonised over as there is one foot stuck in the past (pre-liminal) and one tentatively grasping for a future, post-liminal state. Culturally, we know that people can become trapped in the liminal space, which is why we have many ceremonies and rituals to help us move as smoothly as possible from one state to another – often called ‘rites of passage’. But even with these it can be challenging to find our way through the haze of liminality, and these traditions can be attached to outdated notions of age and stage, as above.

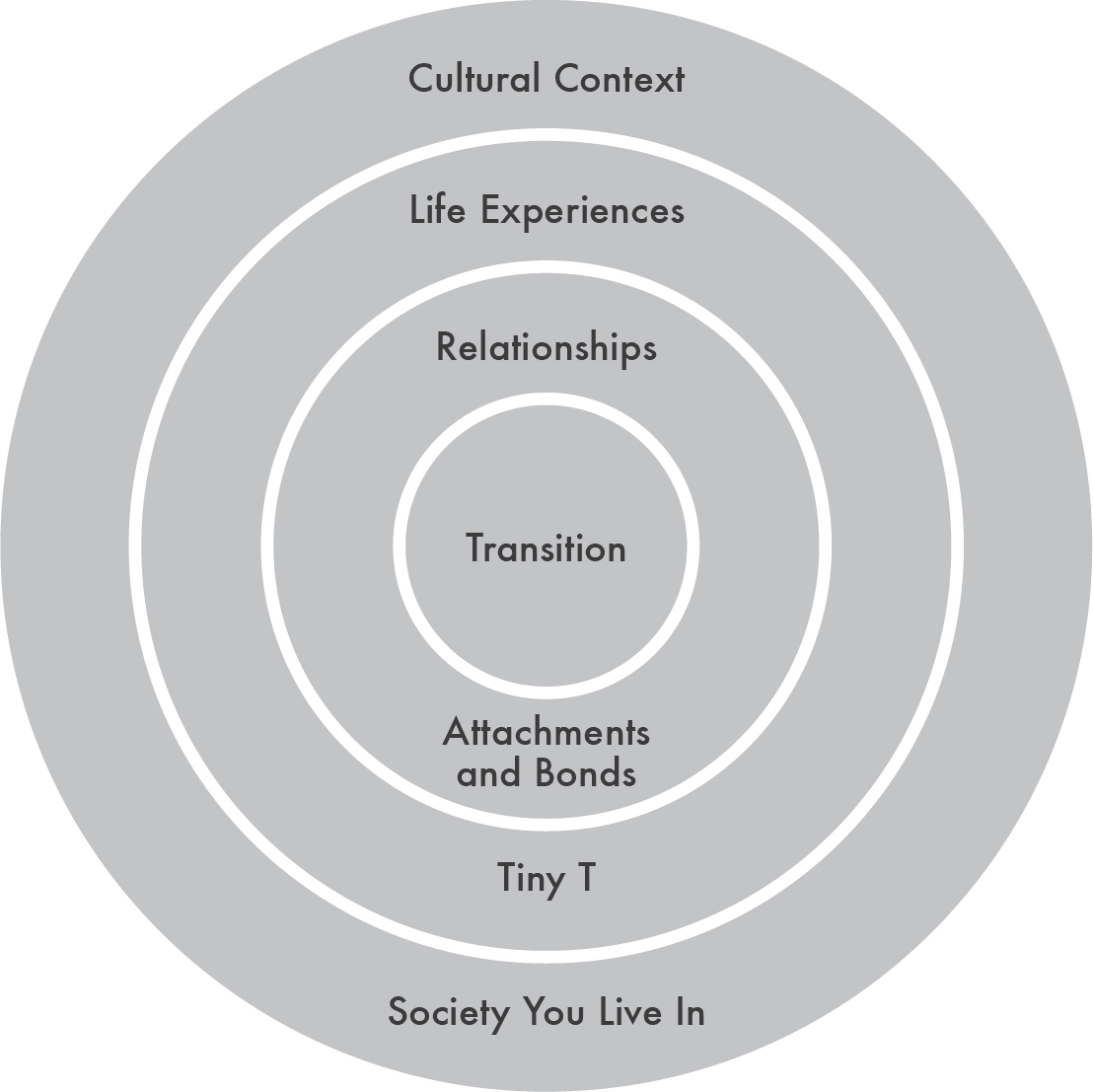

Exercise: The Transition Onion

To help you though this liminal space and into the Acceptance Stage of the AAA Approach when you’re dealing with a tricky transition, there’s a technique I like to call the ‘Transition Onion’ (see Figure 10.1). In the centre of your onion is the transition you’re going through right now – note it down. Next, draw the layer in your onion from the example below – add what you feel has been important to you with regards to this transition; this could be a mixture of experiences and Tiny Ts. Think about the following categories and explore what is influencing your experience of the transition at the centre of your onion:

- Your relationships, attachments and bonds: these can be from early life or connections that you have in the present that you feel are influential in your transition phase.

- Your life experiences, including your Tiny T: you may have discovered different examples of Tiny T in this book and reflected on some of your own that may be keeping you stuck.

- Your cultural context and the society you in live in: depending on the transition you’re exploring, this can include a workplace organisation (for example, if you’re pivoting career or retiring), your community, which might include religion and spiritual beliefs (this is often relevant when dealing with the transition into a partnership, parenthood or the death of a loved one), or even wider societal views that may be influencing how you feel about this transition.

The point here is to highlight how the different levels of our lives impact on how we experience a transition – in other words, it is rarely, if ever, you in and by yourself creating the sense of stuckiness; rather, it is this broader context of our existence that places social-clock expectations on us.

This is where Acceptance as a concept really comes into its own as well, and like so much of the Tiny T work we’ve been doing in this book, the purpose here is to connect the dots between our lived experience and the things that impact on that experience. It’s only when we make these links that the sense of isolation ebbs away, and we can start to work towards the third Action stage of the AAA Approach. Although these personal factors, social expectations and associations often seem so obvious after the exercise, we frequently miss out the Acceptance phase in life – often to our detriment. Let’s take the example of the transition into parenthood – or not. I’ve seen so many people who have chosen to remain child-free yet have struggled within liminal space with this decision until we had the opportunity to explore some of these social-clock expectations and how each layer of their context (as per the onion) was making it difficult for them to move from a pre-liminal state to post-liminal acceptance. The cultural and societal pressure to have children can be difficult for everyone. On the other side of the spectrum, I’ve worked with individuals who have had kids at different chronological points in their life course and felt as if they were too early/too late/doing it at the wrong time in relation to the social clock. This tells us something important about how our beliefs, expectations and our environment affect our experience of transitions. In other words, maybe there is no ‘correct’ time, just a good time for you.

If we go back for a moment to Freya, another key element of her turning-30 crisis that emerged from the Transition Onion exercise – one that hadn’t been in her life-mapping – concerned her family context. When we were discussing both the relationships and attachments layer within the sociocultural circle, Freya mentioned that she was finding it hard to think about what she was going through, as her mum was struggling with the menopause – in other words, like so many Tiny Ts, she didn’t feel that her feelings were worthy as her mum seemed to be having a ‘real transition’. On top of this, Freya’s mum was having problems securing HRT (hormone replacement therapy) for the menopause and so was struggling with a range of symptoms including anxiety and irritability. Freya’s mum was also having to look after her parents (Freya’s grandparents) a lot more, as well as work and support her younger brother – she did seem to have an awfully full plate. Therefore, in Freya’s mind, her mother’s transition negated her experience to such an extent that she hadn’t shared her feelings with her mum for fear of burdening her further. This contributes to an overwhelming sense of isolation.

Menopause and the sandwich generation

There are some transitions in life that are defined by definitive changes in human physiology – menopause is probably the most obvious example in adulthood. Humans are living much longer – since the 1840s, life expectancy in the most privileged countries has been increasing almost linearly by 2.5 years per decade,87 yet the average age for the onset of the menopause hasn’t changed, at 51 years. However, the perimenopause can start ten years before this, beginning in the early- to mid-forties. Considering we now live into our eighties and beyond, it is feasible that half of a biological female’s life could be spent within the process of perimenopause, menopause and then post-menopause, rather than say a quarter when average lifespans were shorter. In many areas of the world, people are also having children later in life, all of which has conspired so that menopause symptoms, older kids either still at home or boomeranging back and elderly parents requiring additional care happen at the same time, under one roof.

About a third of symptoms are severe enough to disrupt everyday activities during this physiological transition – and for many, this could be for over a decade. Some of the early symptoms of the perimenopause include high levels of anxiety and feelings of being overwhelmed, and I have seen countless clients who come to me after having been diagnosed antidepressants by their primary care doctors. Although drugs have their place, recognising that the co-occurrence of a symptomatic menopause with being part of the so-called sandwich generation can be an extremely challenging time can help a great deal and lead to more sustainable ways of coping.

What we mean by ‘sandwiching’ is akin to Freya’s explanation, where there are dual caring responsibilities – and this is often where the conflict between generativity and stagnation, from Erikson’s theory, comes in. Generativity is all about making your mark on the world and contributing to the next generation, and this was often seen as the goal. But we also need to look after ourselves to reduce the chances of stagnation, which can be tough when sandwiched between parents who need more assistance and children still requiring support. Freya seemed intuitively aware of this and so didn’t want to overload her mum with more problems.

However, Freya didn’t factor in the fact that the menopause isn’t all bad – one study from the University of Cambridge reported that during the menopause and post-menopause women felt more able to be open and speak their mind.88 The menopause can also trigger a surge in confidence and strength, with people reporting that they are more in tune with their feelings and less constrained by inhibitions.89 Once symptoms are adequately addressed, that is. I cannot stress enough how real and debilitating the physical and psychological symptoms of the menopause can be – and also how appropriate treatment gives people their lives back. Hence, discussing these topics and the type of conflict that Freya’s mum might be going through was helpful, as it opened a door back to intimacy through open conversation with her mum.

AAA Approach Step 3: Action

The Action phase in the Tiny T Transitions is very much about moving through the liminal space and taking the learnings from previous transitions to new ones. The exercises can be used for any transitional crisis, so focus on what you’re going through right now.

Exercise: Transitional-crisis tug-of-war

This is an exercise that can result in a profound shift during liminality, helping us move through the Acceptance phase to the Action stage of the AAA Approach.90 Start by thinking of what you’ve been struggling with – then work through the following:

Visualise this battle as a superhero nemesis – you could, instead, imagine a monster, demon or any other kind of powerful, nefarious character, but it must be something that has the ability to destroy you.

You are both standing at the top of a volcano, on opposite sides of the deep, black and fiery red pit beneath. You can feel its heat on your face and know the gorge travels down to the molten centre of the earth.

You and the supervillain are in an almighty tug-of-war over the volcano, both pulling and tugging on a thick rope.

Your desire to drag your opponent into the crater feels overwhelming, as your life depends on it. You are using every ounce of energy that you have, but you and your nemesis are well matched in terms of strength and power. It feels like a true battle.

Now … drop the rope.

How does that feel?

I absolutely love this exercise as the mental shift is often immediate. How did that feel for you when you were reading the description? If you can’t find the words, go back to Chapter 3 and have a look at the Emotions Wheel or doodle what you’re feeling – whichever works best for you.

This exercise helps us to see that the struggle is often within ourselves – with our own thoughts and expectations, which can become the focus of the transitional crisis. When we are focused only on the battle – the tug-of-war – it is impossible to see the solutions that exist to help us move through a transition. This is why moving through the AAA Approach is so very important – without Awareness, Acceptance, then Action, we can get lost in the struggle and use all our energy and resources fighting to stay in the same place. Running to stand still or continually pulling on a tug-rope with only ourselves at the other end isn’t fun for anyone – quite frankly, it’s exhausting, often not only for you but also for the people who love you too.

Letter from the future exercise

To figure out how to move into Action, think about a time in the future, in the post-liminal space where everything has turned out pretty darn well. Consider different aspects of your life – both the big and small, the seemingly insignificant to the substantial areas – and imagine how these all would look in a time machine.

Now, take a pen and paper (it’s important that this is handwritten) and write a letter from your future self to the current version of you. You might want to look back at Chapter 2 and think about each area of the Life Assessment – what would each of these areas feel like from the standpoint of fulfilment? Remember, some components may be more important to you than others – family and personal freedom might eclipse financial security and career or the other way round; it’s completely down to what you value.

Explore in detail in your own words what it’s like to be in this future point to your current self – describe how it feels, the context and surroundings, what kind of thoughts you have and the sorts of actions you take on a daily basis. Here are some coaching psychology prompts to help with your letter writing:

Think about your dreams in the life areas that are most important to you – what do these look like?

If you had unlimited resources (not just financial but time, support and encouragement), what would you set out to do?

Try not to just consider your heartfelt dream and ambitions in the frame of your current capabilities, but rather in terms of your potential.

How would this transform the quality of your relationships, work and health?

I use this exercise a great deal as it helps to close the gap between ‘then’ and ‘now’ and progress through the liminal space.

For Freya, this exercise illustrated that she still loved her career, but mostly needed more emotional support from family (including her mum) and at work. Not all stories have a fairy-tale ending though – not in real life anyway – so I wanted to share with you that during the time we worked together Freya broke up with her partner. She confessed that a great deal of the social-clock pressure she was feeling was to do with his expectations of how life ‘should’ pan out, and in her work on the intimacy–isolation conflict Freya felt the need to be free of this romantic, Eros relationship that she felt was expected of her. Indeed, Freya leant into the isolation side of the transitional crisis point, which gave her more independence and helped her to have closer and more meaningful relationships with other people in her life. She stopped caring so much about the ticking of the social clock, and this helped her to become ‘unstuck’.

Longer-term planning for transitions

One of the hardest aspects of a transition is that it can feel unexpected – Tiny T has a lot to do with this as it can trigger a liminal phase such as was the case with Freya and the moral injury she experienced. However, we do know that there are certain transitions that the majority of us will go through, of course bearing in mind individual cultural and societal differences. One example of this in late adulthood is retirement, which usually occurs within the final conflict in adult development proposed by Erikson – that of ego integrity versus despair. Ego integrity is all about reflecting back on one’s life and feeling satisfied with our achievements, whereas a sense of despair comes if we are laden with regrets or feeling that life was wasted.

Whether paid or voluntary, labour in the home or within an outside organisation, work provides us with a sense of purpose, gives structure and routine to our days and can also be an important aspect of our self-identity. Also, most jobs provide social networks and friendships that are fundamental to our wellbeing. These are some reasons why it can be challenging to retire, and indeed many people experience depression post-retirement, particularly if they are forced to retire due to ill health, caregiving responsibilities, or are not able to find another job.91 Even though the world of work has changed from ‘jobs for life’ to more fluid types of careers, most of us will see a close to our working lives at some point. While there are many ways to reinstate the psychosocial elements and structure that work provides, including volunteer work, hobbies and developing new relationships, there are mental barriers that stymie our ability to truly enjoy these years.

Research shows that people with a negative view about growing older tend to struggle more with retirement,92 so if you feel worried about retirement, getting older, or any other transition, here are some ways to make the passage somewhat smoother:

- If you’re about to retire (or even just thinking about a career change), ask others who are now ‘job-free’ to name the three best aspects of their retirement, and three things they’d wished they’d been prepared for. The same goes for every transition – don’t sit in the dark and fear the unknown; take action by seeking out others’ experience and wisdom.

- Discover positive role models within wider culture and media – we tend to only think about role models for young people but they are helpful at any age. Observe the qualities you admire in each role model and how they exhibit their values during this transitional stage, and consider how you can assimilate these characteristics into your daily life. For example, you may follow a fellow retiree who has taken to the stage with stand-up comedy – this doesn’t mean you need to perform a 30-minute set, but you could explore your own sense of humour with your family.

- Finally, look at the transitions that you have successfully navigated in the past and pinpoint the personal resources within you that have helped you traverse sometimes bumpy roads – perhaps your humility, loyalty or integrity helped you move through a transition. Maybe it really was your sense of humour that got you to the other side. Dig deep – you may not have experienced the same transition in the past, but you will have experience that you can draw from based on your core values that will guide you to the next stepping stone of life.

Dr Meg’s journaling prompts for transitions

- What aspects of life have surprised you most? In what ways?

- Think about yourself as a teenager – what three questions would you ask your present self?

- What do you know to be true now that you didn’t know a year ago?

CHAPTER 10 TAKE-HOME TINY T MESSAGE

Transitions are part of life – but this doesn’t mean they are always easy. Normalising transitional phases by having an awareness of what other people also go through is a good starting point for navigating this Tiny T Theme. Accepting that there is a process of letting go of who and what we once were, to enable the next stage of life, is also helpful. Finally, forward planning for the transitions that you will face in the future is a good way to support your psychological immune system in relation to this Tiny T Theme.