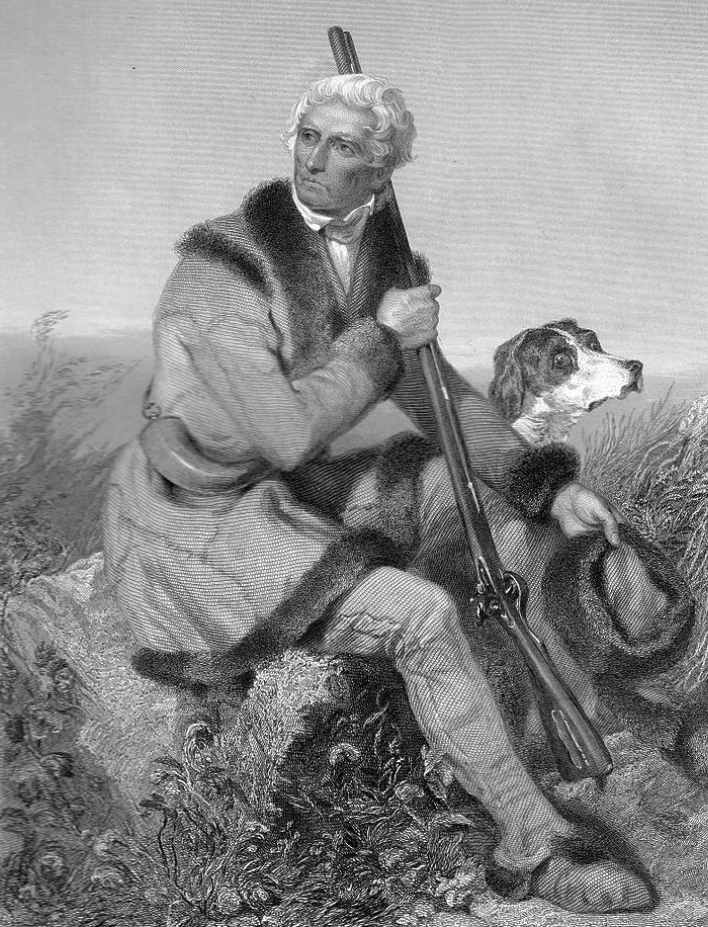

“A good gun, a good horse and a good wife.”

—Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone by Alonzo Chappel, 1862

On May 14, 1804, the Corps of Discovery, the unit of the United States Army that would form the nucleus of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, gathered in Camp Dubois, near the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, to kick off their historic journey. As the final provisions were being loaded onto the keelboat and two pirogues that would sail north up the Mississippi and then into the largely unknown continent, one of the men went from boat to boat testing out the swivel guns that had been mounted on each of the vessels.

One of the guns the men tested that day was likely a small-bore cannon, while the other two were blunderbusses. The blunderbuss was a short smoothbore gun, typically with a flared muzzle that looked something like a bell-bottom. Some historians believe the gun’s name originated from the Dutch words meaning thunder and pipe. Whatever the case, the brawny weapon could be loaded with up to seven musket balls, scrap or iron, and stones.1 Its lock could withstand moisture more effectively than the average musket’s, making it popular with the British Navy and other seafaring types. In some ways it was like the shotguns of the future: devastating at close range. To mount such guns on swivels allowed for a wide arc of movement, making it perilous for anyone who might be thinking about ambushing the boats.

These guns would, as far as we know, be loaded only twice in anticipation of violence. More often than not, they were used to impress the locals—or, more specifically, to impress and deter locals from any thought of attacking—or for saluting crowds, which was why they were fired at around four p.m. the day the men left on their journey. The guns were shot again to greet the boats in St. Louis two and a half years later, on September 23, 1806. Between those two dates, Captain Meriwether Lewis and Second Lieutenant William Clark traversed more than 8,000 miles of largely unexplored terrain, losing only one of their men due to a ruptured appendix.

Lewis and Clark departed the East Coast right before the dawn of the first industrial age, an era that saw great leaps forward in gun technology. At the time Lewis was first procuring his muskets for the western expedition, most of the soldiers and hunters in North America might be able to fire their guns twice in a minute. By the end of the century, men would be able to shoot hundreds of times in that span without ever having to manually reload. They would be able to do this with smokeless powder, self-contained cartridges, and telescopic sights. In a number of ways, Lewis and Clark’s journey portended the technological possibilities of the coming century.

With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the United States had attained approximately 828,000 square miles of territory from France, stretching from the Mississippi River in the east to the Rocky Mountains in the west and from the Gulf of Mexico in the south to the Canadian border in the north. At the eminently affordable price of three cents per acre, President Thomas Jefferson had doubled the size of the republic. Fifteen states would, fully or in part, be carved out of the land procured in this one deal. In the same year, Jefferson commissioned the Corps of Discovery to follow the Missouri River west, past the Continental Divide, to the Columbia River, by which the men could journey to the Pacific Ocean.

The entire Lewis and Clark trip cost the United States government approximately $40,000 (around $8 million today). Yet it helped to forever cement the nation as the dominant power of North America, setting the stage for a century of explorers, trappers, traders, hunters, adventurers, prospectors, homesteaders, ranchers, soldiers, entrepreneurs, missionaries, and masses of Americans spurring a rapid settlement of this vast land. The peopling of the West gave birth to a new culture, disrupted the cultures of the American Indian, and ultimately created the most dynamic economy in the world. Guns would be a vital tool in this project, not only as a means of self-defense and war, but for hunting, trading, and exploration.

Even before the purchase, Americans had long been ignoring the Spanish and French claims and pushing westward. One of these men, the backwoodsman Daniel Boone, famously proclaimed that all he needed was a “a good gun, a good horse and a good wife.”2 It seems unlikely that Boone, born in a log cabin near what is now Reading, Pennsylvania, in 1734 to Quaker parents who had emigrated from England, was exaggerating. Boone’s only real classroom, like many others of his time and place, had been the wilderness. His skills at traversing and surviving on the frontier became legendary, and his amazing tales were firmly tethered to his long rifle, a weapon he had mastered as a hunter in his early teens. “D Boon cilled a bar” read a carving on a nearby beech tree in Washington County, Tennessee, until at least 1917.3

Boone’s specialized frontier skills served him in the French and Indian War, when he was a wagoner for Edward Braddock during the general’s disastrous expedition to Fort Duquesne, barely escaping with his life. Boone also fought in the American Revolution, defending settlements in the proxy war against Indians who were allied with Britain. Boone would really make his name after the war, crossing the Appalachians via the Cumberland Gap, carving out the two-hundred-mile-long path known as “Wilderness Road”—and others—forever opening up the West. Boone led men on months-long hunts into what is now Kentucky. John Filson’s widely read 1784 book, The Discovery, Settlement and Present State of Kentucke, features an appendix detailing Boone’s exploits called the “The Adventures of Col. Daniel Boon,” and it made the first Kentuckian famous around the world.

The Boone story became equal parts Western ethos and mythos, forever defining the prototypical American woodsman. For the next two centuries, the famous frontiersman would be portrayed in illustrations, movies, and TV shows wearing his buckskin leggings and shirts of animal skins. His possessions included a large hunting knife, an Indian hatchet, a coonskin cap (which Boone rarely wore in reality), but most importantly his powder horn, a pouch with lead balls, and his Kentucky rifle. One of the allegedly surviving Boone rifles was used against the Shawnee Indian warriors at the Revolutionary War Battle at Blue Licks on August 19, 1782. As the story goes, Boone was trapped and wounded and pulled off the escape with sixty other American men. A family member, it is said, later found the rifle, which Boone had discarded in his hasty retreat. Although the gun has gone through a number of modifications since its recovery, this .45-caliber Kentucky rifle with “Daniel Boone—1775” carved in the barrel and fifteen notches carved into the stock is still the type of firearm a backwoodsman would have used in the late eighteenth century.

The frontier that Boone traversed was one of violence and turmoil. During the French and Indian War, Native American raiding parties allied with French interests had begun marauding English settlements. More than 2,000 Americans from New Jersey to Carolina were killed by Indians during the war. Pontiac’s Rebellion of 1763 saw more tribes from the Great Lakes joining together and attacking British interests and killing hundreds more colonists. By this time the gun had also proliferated among the Indian tribes and become a necessity for their own survival. As we’ve seen, this increased the deadliness of conflicts—among themselves and with the white man—as well as competition over hunting grounds.

The frontier was a rough place that attracted unsavory characters, adventurers, and those fleeing population centers. Most of them were armed. One traveler named Elias Fordham noted in the 1760s that “there are a number of dissipated and desperate characters, from all parts of the world, assembled in these Western States; and these, of course, are overbearing and insolent. It is nearly impossible for a man to be so circumspect, as to avoid giving offence to these irritable spirits . . .”4 As we will soon see, those on the frontier could only intermittently rely on the law, so guns and knives became increasingly indispensable. And guns would soon be more accurate, reliable, formidable, and cheaper.

More vital even than protection from Indians, the new guns were used to procure food. The significance of hunting is prevalent throughout the diaries of Lewis and Clark. A simple search for the word “meat” in the expedition diaries brings back 783 results—and this doesn’t take into account all the specific instances of animals. As Lewis pointed out, “we eat an emensity of meat; it requires 4 deer, an Elk and a deer, or one buffaloe, to supply us plentifully 24 hours. [M]eat now forms our food prinsipally . . .” He wasn’t kidding. The men likely ate around nine pounds of meat daily when it was available. This sounds like an astronomical quantity to our modern ears, but meat was often what the explorers ate exclusively.

Though the Lewis and Clark Expedition hunted deer, rabbit, squirrel, wild turkey, elk, beaver, and other animals they were acquainted with on the East Coast, soon they were running across animals they’d never seen before. The expedition tried and failed to kill something called a “Prairie Wolf.” It was the first time Americans had noted seeing a coyote. They tried to catch “praire dogs”—in the process naming the animal forever. In the summer of 1804, the expedition ran across a herd in the Great Plains that became a staple of nutrition from then on. None of the participants in the American expedition had hunted buffalo before, but they quickly became fans, eating everything from the rump to the tongue. In due time the buffalo became so abundant that the explorers ate the tongues and left the rest to the wolves.

The explorers also hunted (and on occasion defended themselves from) grizzly bears. The bear, which was used to feed the men but also for their expeditionary needs, proved exceptionally difficult to bring down with the weapons the men had in hand. The musket’s stopping power from fifty yards was not enough to kill the beast. Considering the musket’s low accuracy at long range, they had to get close and shoot the grizzly in the head. This was a dangerous proposition.

Of the two famous explorers, Lewis was more proficient in the use of guns. Decked out in moccasins and a fringed deerskin jacket, Lewis would have been recognizable to Boone or any of the first western explorers. Everywhere Lewis went, he carried a notebook, meat jerky, a large knife, his flintlock pistol, a half-pike (what was called an “espontoon”), and his rifle. A fine marksman, Lewis used the pike as a walking sick but also as a rest for his rifle to allow him a steady shot. Lewis had been a member of the Virginia state militia and then the imposing force of 13,000 militiamen who marched with George Washington to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791 to 1794, later joining the army proper and achieving the rank of captain. By 1801 he had become President Thomas Jefferson’s private secretary, leading to his role as leader of the expedition.

In preparation for this trip, Lewis had traveled to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, home of the Kentucky rifle, in 1803 to oversee “the fabrication of the arms with which he chose that his men should be provided.” Over the years, the prestige of the Lancaster gunmakers had not abated. There were around sixty of them working in and around the city by the early 1800s.5 Lewis purchased flintlock rifles in Pennsylvania, but that was not the end of the shopping spree. That month he wrote Jefferson that “my Rifles, Tomahawks & Knives are preparing at Harper’s Ferry, and are already in a state of forwardness that leaves me little doubt of their being in readiness in due time.”

The Harpers Ferry armory, along with another one in Springfield, Massachusetts, would become the leading centers of gun technology for the next century. They played an integral part in spurring America’s first industrial revolution and experiments in interchangeable parts and precision machinery, soon to be imitated in other trades and by other nations.

One of the prevailing concerns of Americans between the Revolutionary War and War of 1812 was being pulled into another conflict with the British or the French. In 1798, after France began menacing American ships on the East Coast, Congress voted to create a 15,000-man standing army and gave the president authority to double that number in an emergency. Less famously, the legislation also authorized the creation and production of 30,000 muskets to stock the new American armory.6

During the Revolution the fledging nation had created a dispersed system of small armories to maintain and store munitions. As the internal threat began to subside at the end of the war, a centralized armory was deemed necessary by Washington. The general approved a site in Springfield, Massachusetts, due to its geographical proximity to the roads and waterways that allowed them to both import resources and export the final product more efficiently. By 1793, Springfield was home to an array of weapons left over from the war. Within a few decades, however, it was developed into the production center for new American arms, a role it would fulfill until well into the Vietnam War.7

The southern states, unsurprisingly, wanted an armory as well. So a year later Congress passed a bill calling on the executive branch to build another center for “erecting and repairing of Arsenals and Magazines” in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. In the long run, the second armory would be less successful than Springfield due to deficiency in waterpower, location, and mismanagement. It saw a major renovation before the Civil War, and became infamous when the abolitionist John Brown raided the armory before attempting to initiate an armed slave revolt in 1859.

Springfield 1795 flintlock musket

The Model 1803 rifle, a short-barreled gun with a .54-caliber flintlock, had been adopted by Jefferson’s secretary of war, Henry Dearborn, to become the Army’s official rifle. It was the first gun manufactured in an American armory, the Harpers Ferry Armory producing more than 4,000 of these rifles between 1803 and 1807.8 The Lewis and Clark Expedition may have carried a prototype of the gun, but we don’t know for sure. None of the weapons the Corps of Discovery carried is known to exist today. All of the weapons, as well as musket balls, powder horns, axes, and other arms, were sold at a public auction in St. Louis shortly after the expedition’s end in September 1806 for a grand total of $408.62.

In truth, the duo’s cache would soon be antiquated anyway—except for one gun, that is, which was a portent of the precision, speed, firepower, and innovation that would come to dominate gunmaking over the next fifty years. The expedition might have brought only one, but it proved to have an outsized importance, not only impressing locals but discouraging them from resorting to violence against the expedition. On the first page of the first entry of Lewis’s journals, in fact, the explorer introduces us to the “air gun.”9

Lewis and Clark mention the air rifle thirty-nine times in the journals of the trip.10 In nearly every instance that the expedition encountered a new Native American encampment, the duo decked themselves in their most impressive, colorful, and polished military uniforms. They then marched into the native camp with flags, attached bayonets, and donned swords as if they were meeting a dignitary in a European court. The Indians were given an array of beads, medallions, and colorful clothing as gifts. Then Lewis showed off the air gun, a weapon that even tribes that had experienced guns before had never encountered. According to Lewis, many of the tribes considered it “something from the gods.”

A private on the expedition named Joseph Whitehouse described one meeting in the summer of 1803, at a Yankton Sioux village along the Missouri River: “Captain Lewis took his Air Gun and shot her off, and by the Interpreter, told them that there was medicine in her, and that she could do very great execution.” Indeed it could. The Indians stood amazed as Lewis kept firing the gun without reloading. When he was done “the Indians ran hastily to see the holes that the Balls had made which was discharged from it. [A]t finding the Balls had entered the Tree, they shouted a loud at the sight and the Execution that suprized them exceedingly.”

Lewis wrote that he purchased the air gun in 1804, although he gave no specifics about its origin or model. The explorer would keep both the specifics of how the lock functioned and the number in his possession a secret from nearly everyone. The idea of using air pressure to fire a lead ball goes back to the 1500s. The earliest surviving example of an air rifle, dating to around 1580, can still be seen in Stockholm’s Livrustkammaren (Royal Armory) museum. But it was in 1780 that an Italian inventor in the Austrian province of Tyrol named Bartolomeo Girandoni developed an air-powered rifle that could fire .46-caliber lead balls. He sold the idea to the Austrian army, which used the weapon from 1780 to around 1815. An Austrian government report in 1801 found that Girandoni air guns had been lost in battle, so it’s plausible that many were circulating in Europe and one had made its way into the hands of an American gun merchant.11

Whatever the case, the gun featured a higher rate of firing capacity than any other weapon in existence at the time. It was a smokeless repeating gun that could hold up to 800 pounds of compressed air. Its tubular magazine held up to twenty-two .46-caliber round balls. It could fire up to forty times before it began losing muzzle velocity.12 It was one of the first truly successful attempts at a repeating gun. The problem was that it would take around 1,500 strokes of a hand pump to create the pressure needed to fire the weapon. Its specialty parts were nearly impossible to fix.

Most of the guns Lewis and Clark brought with them retained the downsides, glitches, and vagaries that had plagued the machine for over two centuries. But—conceptually speaking, at least—the air gun was a weapon of the late nineteenth century. It gave men a glimpse into the kind of potency that would soon dominate gun technology through the revolver, the repeating rifle, and the automated gun.

• • •

For now, with the immediate gains made in workflow, division of labor, and interchangeable parts, American arsenals produced around 10,000 muskets per year in the early 1800s.13 Many people contributed to make this impressive feat possible. One was the noted inventor Eli Whitney. Born in 1765, the Yale-educated engineer from Massachusetts became most famous for inventing the cotton gin, a device that streamlined the process of extracting fiber from cotton seeds (although some historians dispute Whitney’s claim to it). Whitney portrayed himself as a pioneer in the new musket-making process, a man who wrestled with how to produce all the components in the most efficient way. “A good musket is a complicated engine and difficult to make,” he wrote, “difficult of execution because the conformation of most of its parts correspond with no regular geometrical figure.”14 For years he would be credited for pioneering the machine-made interchangeable parts. The truth is more complicated. Whitney had obtained his huge government contract to produce weapons before he ever wrote or suggested interchangeability. While the historical consensus acknowledges him as a competent producer of guns, he also likely exaggerated his own role in the early production of firearms.

Whereas Whitney took more credit than he deserved, others would not get enough. If one person can lay claim to have systemized and standardized the manufacture of weapons, it was John H. Hall. Born on January 4, 1781, in Portland, Maine, the day before Richmond, Virginia, was burned by British naval forces led by Benedict Arnold, Hall grew up with a fascination with gadgets. A volunteer in the Portland Light Infantry, Hall worked as a cooper, carpenter, and shipbuilder, attaining a hard-boiled determination that at various times aided and hampered his career.

Hall filed his first patent for a breech-loading gun (a technology that, as we’ll see, soon dominated rifle making in the mid-1800s) at the age of thirty, only to find out from William Thornton, the superintendent of the patent office, that the gun had already been conceived of by someone else. Incredibly, that someone else was none other than William Thornton. Skeptical of this astonishing coincidence, Hall traveled to Washington to confront Thornton and take a look at the evidence for himself. Thornton, unsurprisingly, was unable to provide any substantial proof of having designed such a gun. After spending months lodging complaints with government officials, Hall decided to avoid years of bureaucratic entanglements and instead hand Thornton half of all royalties moving forward. Hall’s gun became not only the first breech-loading rifle patented in the United States but the first new gun patented, period.15

At the time, most military long arms were smoothbore .69-caliber muzzle-loading flintlock muskets. Hall’s rifle “could be loaded and fired . . . more than twice as quick as muskets . . . ,” wrote the inventor in his patent application. “[I]n addition to this, they may be loaded with great ease, in almost every situation.” Hall began advertising his gun in 1812, but sales were slow. It was unfamiliar, difficult to maintain, and carried a hefty price of $35 per gun.16

Military leaders were also initially dubious about the functionality of this new technology. Testing was delayed for years due to the War of 1812 and postwar funding issues. Hall continued to push for civilian sales and a military contract, making the case that speedy reloading was the future. “The time necessarily required in the loading of Rifles, has long formed a serious obstacle to their general use. It is even conceived by some,” Hall later wrote, “that circumstances outweigh all the advantages to be derived from superior accuracy.”

Finally, in 1817, Hall produced one hundred handmade muskets for evaluation by the U.S. Army Ordnance Board. Impressed, the government offered Hall an abandoned sawmill that was perched on the Shenandoah River at the Harpers Ferry armory. Due to the complexity of this new firearm, as well as the requirement that the parts be interchangeable, Hall spent nearly five years developing the tools and machinery necessary for the production of his rifles. Once done, it outperformed every other model in contention, proving exemplary in testing, one firing over 7,000 times without a single malfunction.

In 1819 the Hall-patented rifle was adopted by the U.S. Army, although the gun was not widely used for years. The Hall carbine, produced in varying calibers, would become the principal long arm of the United States cavalry for the next two decades.17 It would be used in the Black Hawk War in Illinois and Michigan Territory and the Seminole War on the Florida frontier. A unit of this type required a carbine as its primary arm, as it was easier to use when fighting on horseback, and Simeon North took on the task of developing a breech-loading carbine based on Hall’s rifle design. The result was a .58-caliber smoothbore percussion arm that featured a sliding rod bayonet.

During his two decades at Harpers Ferry, Hall developed a number of innovative tools, including drop hammers, stock-making machines, balanced pulleys, drilling machines, and special machines for straight cutting—a forerunner of today’s milling machine, a critical tool used in the fabrication of precision metal firearm components.18 His precision-manufactured machine-made rifle parts were completely interchangeable, thus eliminating the need for skilled craftsmen to repair broken arms. As with other important techniques, many innovators took part in creating the “American system of manufacture,” but Hall was certainly one of the method’s pioneers and played an important role in its realization.

By most accounts, Hall was not an easy man to do business with: he had constant run-ins with his superiors. At one point there were congressional calls for more study of the utility and costs of Hall’s rifles, the aim of which was to show that they were a waste of funding. In the end, the episode only enhanced Hall’s reputation when the resulting report found that the guns “have never been made so exactly similar to each other by any other process. [The] machines we have examined effect this with a certainty and precision we should not have believed, till we witnessed their operation.”19 After this, Hall’s ideas spread rapidly to the Springfield Armory and other private armories. He devised gauging systems to maintain accuracy, and when Simeon North began building Hall rifles in Connecticut, these gauging systems ensured that parts were interchangeable between rifles from the two armories. Others in the private sector would soon take those ideas and, without bureaucratic meddling, perfect them and change the way the guns operated.