“The discharge can be made with all desirable accuracy as rapidly as one hundred and fifty times per minute, and may be continued for hours without danger.”1

—Scientific American magazine

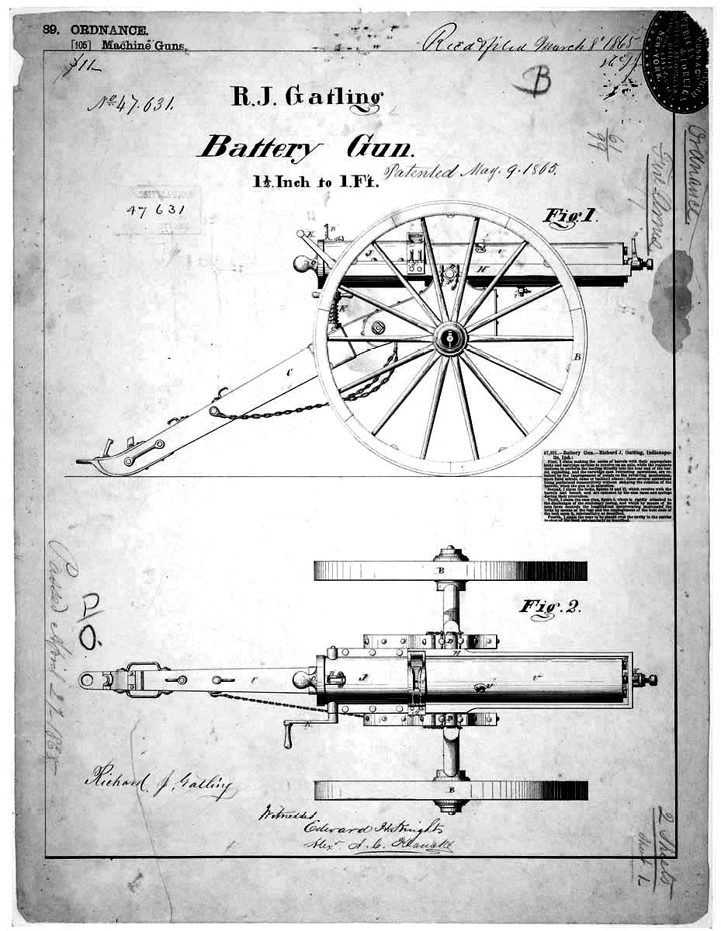

Battery Gun by Richard Jordan Gatling

They showed us the new battery gun on wheels—the Gatling gun, or rather, it is a cluster of six to ten savage tubes that carry great conical pellets of lead, with unerring accuracy, a distance of two and a half miles,” Mark Twain remarked in one of his 1868 columns. “It feeds itself with cartridges, and you work it with a crank like a hand organ; you can fire it faster than four men can count. When fired rapidly, the reports blend together like the clattering of a watchman’s rattle. It can be discharged four hundred times a minute! I liked it very much.”2

Dr. Richard Jordan Gatling’s hand-driven machine gun was far more reliable and faster than any other gun before it, introducing to the battlefield the prospect of continuous firing of weaponry. Twain may have found the creation to his liking, but for millions of soldiers in the upcoming century the idea of unremitting fire added a specter of violence that altered conflicts in the bloodiest way imaginable—for both the soldiers and their commanders. When a Union army of the Civil War sparingly used a hand-cranked Gatling gun for covering fire during skirmishes around Petersburg, Virginia, in 1862, it held little consequence. By the time World War I ended, the British estimated that machine guns had been responsible for somewhere around 80 percent of all casualties.3

None of this was the intention of Gatling. Born on a southern plantation to a slave-owning father in North Carolina in 1818, the inventor, who would have friends on both sides of the Civil War, lived a restless life, moving often and dabbling in an array of professions, including spending time as a county clerk, merchant, planter, and dry goods store clerk. Gatling moved to St. Louis in 1844 and became a doctor, or what passed as a doctor in those days, although he never practiced, before ending up in Indianapolis on the eve of the Civil War, where he worked in speculative real estate.

In 1861, the year war broke out, Gatling attended a lecture in Ohio where he heard a speaker expounding on the lifesaving benefits of breech-loading weapons and quicker reloading times. The speech sparked an idea that began to percolate in his mind. Spurred by the horrors of war, his notions about speedy firing began to gain traction. “It occurred to me,” he wrote a friend in 1877, recalling the daily comings and goings of the wounded, sick, and dead in the early days of the war, “that if I could invent a machine—a gun—which could by its rapidity of fire, enable one man to do as much battle duty as a hundred, that it would, to a great extent, supersede the necessity of large armies, and consequently, exposure to battle and disease be greatly diminished. I thought over the subject and finally this idea took practical form in the invention of the Gatling Gun.”

Gatling had already witnessed wounded Union infantrymen returning to Indianapolis. Although the men he saw slogging back from the bloody battlefields of the Civil War were lucky to have escaped with their lives, many had done so with catastrophic injuries. With the great technological advances of weaponry in the mid-1800s came a wave of shattered bones and lead amputations. The sheer numbers of casualties were shocking. For many years Civil War casualties were thought to be around 620,000, but now some historians put the estimates much higher. “The number of men dying in the Civil War is more than in all other American wars from the American Revolution through the Korean War combined,” J. David Hacker, a demographic historian from Binghamton University in New York, has written. “And consider that the American population in 1860 was about 31 million people, about one-tenth the size it is today. If the war were fought today, the number of deaths would total 6.2 million.” Using digitized census records from the 1800s, Hacker has recalculated the number of casualties to be closer to 750,000, and many scholars are increasingly coming around to this view.

Whatever the actual number was, it was unprecedented. It is true that most Americans who died during the war did so from disease and factors that did not include being shot at by the enemy. Still, at least 100,000 from each side perished in battle. The Civil War featured soldiers with increasingly advanced weapons and ammunition, and yet most of the military leaders didn’t grasp the consequences, using antiquated methods to deploy their troops and weapons.

It is unsurprising, then, that doctors were initially unprepared to deal with the overwhelming number of wounds and injuries. In the mid-nineteenth century, medical school was often no more than two years—if that. Many Army doctors at the outset of the Civil War were nothing more than political appointments or, worse, quacks. There was not only a dearth of doctors, but of the doctors who did deal with bullet wounds, only a fraction had ever performed surgery before the war. Of the 11,000 Union doctors, only 500 had any surgical experience before the war. In the Confederacy, only 27 of the 3,000 doctors had prewar surgical experience.4

Yet the truth about how Americans wrestled with the repercussions of new gun technology is complicated. The common perception is that physicians during the Civil War knew precious little about sterilization or infections, and permitted unsanitary conditions that cost many lives. As the war progressed and family members saw the results of these amputations and wounds for the first time, the reputation of the doctors diminished and a distorted view of their work began to first coalesce.

It is true that surgeons did not even wash their hands before sticking and prodding wounds to determine if they should amputate. They often used blood-splattered sponges and dipped them into dirty water to clean the wounds. Most of this was due not to negligence but rather a lack of knowledge. In many ways, the Civil War saw great advancements in medicine. Doctors were not the hapless butchers often depicted in movies and novels. One of the grisly benefits of the war, in fact, was the ability of doctors to study outcomes. As war pushed man toward innovative new ways of killing, it also pushed others toward advances in lifesaving techniques.

Compiled by the government, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion was a massive six-volume work detailing medical care during the war. It found that of the 174,000 wounds inflicted during the conflict, around 4,600 were treated with surgical extraction and nearly 30,000 ended up as amputations. The mortality rate among the latter was 26 percent. To put this number in context, during the Franco-Prussian War fought in 1870, the mortality rate for amputations was 76 percent.5 Moreover, by 1846, anesthesia using ether had been developed. The next year saw the use of chloroform. Anesthesia was used by war doctors in approximately 80,000 cases for the Union and 54,000 for the Confederates, saving thousands of soldiers horrifying pain, most often brought on by amputation. Civil War doctors soon discovered that amputation performed within twenty-four to forty-eight hours after being wounded—“primary amputation”—saved lives. These procedures were performed quickly by sawing off limbs in a circular motion. The amputations were most often left to heal by granulation, in which thick tissue was allowed to naturally form around the wound. If not, surgeons used the “fish-mouth” method, cutting flaps of skin that were sewn into a rounded stump. These amputations were many, and they would be a constant reminder of the war.

This is what Gatling saw in 1871, and this is what he wanted to stop with a high-powered rapid-fire gun. Often depicted as a tragic figure, Gatling attempted to belittle the importance of his invention, framing it as a means of diminishing mass death rather than creating it. “The best way to ameliorate war is to shorten it,” he would say.6 That it would not do—although it would make him rich and famous. Whether his dovish intentions were merely a retroactive justification after remorse struck the man is certainly up for debate. We can’t bore into Gatling’s soul to find out. Of course, as we’ll see, if Gatling hadn’t invented the rapid-fire gun, someone else would have.

What we do know is that Gatling, a completely self-taught mechanical engineer, almost solved the long-standing problem of automatic fire. Throughout history, engineers had attempted to rig guns that could fire multiple rounds without reloading. From the first days of gunpowder, soldiers rammed as many pellets and shards as they could into pot guns. Leonardo da Vinci drew up plans for a thirty-three-barreled organ gun with three rows of eleven guns each, all connected to a single revolving platform. Attached to the sides of the platform were large wheels. Ribauldequins—guns that often featured ten or more iron barrels in a row—were first said to be used by King Edward III of England in 1339 against France, and would be used, in various forms, by numerous armies over the next centuries.

In the mid-1500s, Sir Francis Walsingham, then secretary of state, turned up at court with a mysterious German who, “among other excellent qualities,” had promised to produce a harquebus “that shall contain balls or pellets of lead, all of which shall go off one after another, having once given fire, so that with one harquebus one may kill ten thieves or other enemies without recharging it.”7 There is no record of what became of the experiment. In the early 1700s an Englishman named James Puckle patented a flintlock cylinder crank-propelled gun that could hold eleven shots. It probably never went past the prototype stage.

Even as Gatling was attempting to build his gun, a number of other inventors were already toying with the idea. In 1861, the Billinghurst company would test its Billinghurst-Requa battery gun in front of the New York Stock Exchange, hoping to lure investors.8 Invented by a dentist named Josephus Requa—who was apprentice to once-prominent upstate New York gunmaker William Billinghurst, thus the name—the gun fired off 175 shots per minute, reaching 225 shots in a minute and fifteen seconds in later trials. The gun featured twenty-five horizontal barrels mounted on a light artillery carriage that were loaded at the breeches with “piano hinge” magazines with .52-caliber cartridges. The gun used percussion caps on one nipple that detonated one round that passed in domino fashion from one cartridge to the next until it was exhausted. Although the gun had its champions, including members of the New York Light Artillery, it was barely used by the Union, as it often failed in damp weather and was difficult to reload and aim.

Around the same time Requa was impressing investors on Wall Street, an edition of Scientific American reported that an offer had come from an English firm to sell the Union Army an armament called the “Perkins steam gun” that could discharge ten twelve-pound balls per minute. Although the inventor, Jacob Perkins, had died more than a decade earlier, he was already well-known to many Americans. The Massachusetts-born Perkins, who had moved to England after his banknote engraving methods (soon to be widely adopted), had a difficult time finding traction with United States investors. Perkins was behind numerous well-received creations, including the first patented vapor-compression refrigeration cycle.9 The steam-powered gun generated some excitement among political leaders on both sides of the Atlantic, including Lincoln.

Military leaders, on the other hand, were less impressed. Steam, as it turned out, was a lot less robust as a propellant than gunpowder, making a “steam gun” a step backward. Or, as the Duke of Wellington is said to have quipped after seeing an exhibition of the weapon, “if steam guns had been invented first, what a capital improvement gunpowder would have been.”10

Inventors kept getting closer. The year Gatling witnessed the wounded hobbling back to Indianapolis, a man named Wilson Ager was already testing a hand-cranked machine gun in America. President Lincoln, after an exhibition of Alger’s so-called Coffee Mill Gun, wrote, “I saw this gun myself, and witnessed some experiments with it and I really think it worth the attention of the Government.”11 The idea was sound, the execution less so. Military leaders complained that the Coffee Mill Gun overheated and failed to feed ammunition and allowed gas to escape from the breech during firing, lowering the weapon’s velocity. By March 1863, Scientific American reported that Coffee Mill Guns had “proved of no practical value” and the remaining guns were put in storage in Washington. The Union had ordered a number of these unreliable contraptions, in turn souring Lincoln on Gatling’s similar invention, even though the president was typically a fan of firearm innovations.

“I assure you my invention is no ‘Coffee Mill Gun,’ ” Gatling wrote in an 1864 letter. “The object of this invention,” he went on, “is to obtain a simple, compact, durable, and efficient firearm for war purposes, to be used either in attack or defense, one that is light when compared to ordinary field artillery, that is easily transported, that may be rapidly fired, and that can be operated by few men.”12 But it was like a Coffee Mill Gun. While Gatling’s brainchild would evolve over the years, at this point the fundamental mechanism was similar. It was equipped with anywhere from four to ten barrels—most of the time six—organized around a central axis featuring a magazine that loaded each barrel separately. A person could theoretically fire the barrel as fast or as slow as the hand-crank allowed. In reality, since the metal barrel experienced a tremendous heat, each barrel had an opportunity to cool as it revolved.

When it worked, it was terrifying. In an era that was not fully removed from the use of flintlock muskets, this constituted a nearly incomprehensible speed of fire. Early models of the gun could shoot 200 rounds per minute. Later models fired up to 1,000 rounds per minute. In 1870 it was reported that Gatling personally fired 1,925 rounds in 2 minutes and 30 seconds.13 While the rapidity was certainly impressive, what also enticed those who tested the gun was its simplicity. “The mechanical construction is very simple, the workmanship is well executed, and we are of the opinion that it is not liable to get out of working order,” a Union officer reported after trials of the gun at Washington Navy Yard in 1863.14 Gatling, normally a reserved man, participated in a number of public demonstrations to impress crowds and grow more comfortable with salesmanship. “The newly invented gun of Richard J Gatling, of this city, was put through an experimental trial yesterday, with blank cartridges, at the State House square, in the presence of the Governor and a large crowd of citizens,” one Indiana newspaper reported.15 “It operates very successfully and will prove to be a weapon of war both novel and deadly.”

Some Army officers bypassed the Army ordnance bureaucracy and purchased Gatling guns for their troops. The flamboyant Union general Benjamin Butler, for instance, bought twelve of them in 1864. Gatling claimed that Butler “fired them himself upon the rebels. They created great consternation.”16 A lieutenant from the 4th New Jersey Battery wrote a friend that “Gen. Butler brought one his favorite Gatling guns, which throws 200 balls per minute, in this Battery on Friday, and pointing it through one of the embrasures, began to ‘turn the crank.’ This drew the fire of the Rebs on us, and one captain and a private were severely wounded.” In the same year, a Gatling demonstration so impressed future Democratic Party nominee for president Winfield Scott Hancock, he ordered a dozen for his corps. It was only at the end of the war that the Army officially adopted sixty Gatling guns for general use.17

Yet, overall, the Gatling gun saw scant action during the war—and when it did, it was near the end of the conflict. Despite all the potential and plaudits, it would take years for the gun to be ready to be adopted by the U.S. Army as a standard armament. The early models were heavy and cumbersome, mounted on old cannon carriages that were difficult to move during battle. The early models did not provide lateral fire, which often made them nearly useless. After the war, the Army created a specialized wood carriage to lighten the burden and gave it a 12-degree sweep at 1,200 yards, but the life span of the gun would be short.

Gatling was more successful selling his guns abroad to the Russians, Austrians, and Turks. Other Europeans had already taken up similar lines of thinking during the mid-1800s. The Mitrailleuse gun—mitraille means grapeshot—was a multibarreled rifle gun that could fire up to 444 times per minute. Invented by Captain Fafschamps and Joseph Montigny in 1851, it went through numerous iterations. By 1867, Emperor Napoleon III of France was so impressed by a display of the weapon that he made a large purchase for his army. However, its performance in battle would be lacking, as it suffered from many of the tactical problems of the Gatling gun. It was heavy and difficult to move and offered little lateral fire. It was dropped within two years. Some historians argue that the Mitrailleuse’s poor showing in the Franco-Prussian War resulted in lagging interest in machine guns for many European armies. It cost them.

Many other inventors took their shot. There was the Nordenfelt gun, invented by a Swedish engineer named Helge Palmcrantz (it was financed by a banker named Thorsten Nordenfelt, thus the name), which was an updated version of the Mitrailleuse. Patented in 1873, it was also a multiple-barreled gun that was mounted laterally, and a wooden strip would feed the gun at a rate of 350 shots per minute by a hand-cranked mechanism that fed cartridges in through an overhead hopper. There was the Gardner gun, invented in 1874 by William Gardner of Toledo, Ohio, a former captain in the Union Army. The British Army took an interest after seeing the five-barreled gun fire 16,754 rounds before a failure occurred, with only 24 stoppages. When operator-induced errors were taken into account, there were only four malfunctions in 10,000 rounds fired. The Army adopted the weapon, although its introduction was delayed because of opposition from the Royal Artillery seeing some action. There were others: the Lowell Machine Gun and the Wilder Machine Gun, to name just two.

Each of them brought some specialized aspect to the table. In the end, none of them were successful, because a new gun—one that could sustain self-perpetuating fire—was about to change everything.