We are what we repeatedly do.

Excellence, then, is not an action, but a habit.

—ARISTOTLE

In chapter 11, I talked about the success my friend’s coach experienced when he mentally rehearsed a game, inning by inning, hitter by hitter, and then went out and pitched that game, exactly as he had thought it through the night before. He enjoyed great success against a team that had previously plagued him. Just imagine how powerful a tool mental rehearsal can be when we use it to improve our being, and not merely our baseball skills. For now, though, let’s stick with baseball for a bit longer.

In this chapter, we’ll outline the most important element of mental rehearsal. None of the mental preparation my friend’s coach went through would have mattered if he hadn’t gotten himself to the ball field, warmed up in the bullpen, and then faced live hitters in a real game. Just as he’d envisioned, he had to go out there and demonstrate his skill, show command of his pitches, display his ability to locate the ball in and out of the strike zone. He went from using just the mind, to using the body and the mind.

Demonstration is the crucial final step from mental rehearsal to personal evolution. My baseball-playing friend, a pitcher himself, learned a term that he applied to certain players: “He’s a six o’clock hitter.” That hour was the time when players took batting practice before the actual game. These guys could put on prodigious displays of hitting—sharp line drives to the gaps and mammoth tape-measure home runs. The problem was, when the actual game started, they couldn’t hit their body weight in batting average, nor could they generate the kind of power they did in practice.

Thus, it is vital that we move beyond mental rehearsal to actually put into practice the evolved ideal of our imagination. Imagine a concert pianist who does his or her best work in practice sessions, but struggles during a concert; a professor who executes faultless presentations in his mind the night before a class, but succumbs to nervousness in the lecture hall; or a spouse who is the model of understanding on the drive home from work, but devolves into an impatient pouter as soon as he or she comes through the door. Without the playing field of life and the opportunity to live what we have mentally rehearsed, we will never embrace the true experience and all of its sensory memories that the body as well as the mind can enjoy.

How can we take this evolutionary step from thinking to doing, and then to a state of being? To get there, I’ll add just a few more concepts to our knowledge base. We’re already beginning to appreciate that being it—exhibiting whatever behavior we want to embrace—means to have our evolved understanding and our experiences so hardwired and mapped into our brain that it’s no longer necessary for us to even think about how to put our new skills into practice. Nike has reminded us to “just do it.” My goal is to take that decree out of the level of clichéd sloganeering and demonstrate how we can integrate all our skills and knowledge to make that truism a reality. Putting into practice what we have learned, we can evolve our brain and break the habit of being the old neurochemical self. When we form a new mind and a more evolved identity, we will “just be it.”

Let’s start by refining our understanding of how we form and use memories. In previous chapters, we described memory as thoughts that stay in the brain. Primarily we register conscious thoughts in the brain by recalling, recognizing, and declaring what we have learned. Conscious thoughts can include short-term and long-term memories, or semantic and episodic memories. Knowledge, short-term memories, or semantic knowledge (for our purposes, these have similar meanings) are filed away in the brain by the intellectual mind. On the other hand, experiences, long-term memories, or episodic memories (also synonymous) are formatted in the brain by the body and the senses, in order to reinforce the mind and the body to remember even better. The latter types of thoughts tend to stay in the brain longer, because the body participates in sending important electrochemical signals to the brain to create feelings.

Most memories fall into the category of explicit or declarative memories, those we can consciously retrieve at will. Here’s a helpful way to think of what makes these kinds of memories distinct: we can declare that we know that we know them. Declarative memories are statements like the following: I like garlic mashed potatoes, my birthday is in March, my mother’s name is Fran, I am an American, the heart pumps blood, and I pay taxes each April 15th. Also, I know many things about spinal biomechanics, I know my address and phone number, and I know how to plant a winter garden.

Explicit, declarative memories mainly involve our conscious mind. I can consciously declare all of those above thoughts. I learned about these things either via knowledge (semantically) or experientially (episodically) in order to consciously remember them. Accordingly, there are two ways we form declarative memories: through knowledge and through experience.

The neocortex is the site of our conscious awareness and, therefore, our explicit memory storage. Various types of explicit memories are processed and stored differently in the brain. Take, for example, the different ways our neocortex handles short-term versus long-term memory.

Short-term memory is held in our frontal lobe for the most part, so that we can make our way in the most functionally efficient manner. When we memorize a phone number, we repeat it in our mind as we walk from the phone book to the telephone, and hope for the best. It is our frontal lobe that maintains those numbers in our head while we scramble to take immediate action. This feat involves not only laying down new memories, but also being able to retrieve them.

Long-term memory is also stored in the neocortex, but the means by which we store new information long-term is a little more complex. When our sensory organs take in data from a novel experience, the hippocampus (as you’ll recall, a part of the midbrain that is most active when we are making known the unknown) functions as a kind of relay system: it takes that information from the sensory organs and passes it on to the neocortex through the temporal lobe and its association centers. Once that learned information makes it to the neocortex, it is distributed throughout the cortex in an array of neural networks. Long-term memories, therefore, involve both the neocortex and the midbrain.

To recall a long-term memory, when we fire the thought associated with that memory, we essentially turn on the neural patterns in a specific sequence that will then create a particular stream of consciousness and bring it to our awareness. If the neocortex is like a computer hard drive, then the hippocampus is the save button: as we make different memories appear on the screen of our mind, they are stored when we hit the key to save the file. In effect, we can also perform “file open” to retrieve those memories stored in the neocortex.

As a side note, we possess another kind of short-term memory that helps us learn. In the 1960s, scientists coined the term “working memory.” Though some think of this as a synonym for short-term memory, the two have slightly different meanings, since working memory emphasizes the active, task-based nature of the storage. We use working memory particularly in carrying out complex cognitive tasks. The classic example is mental arithmetic, in which a person must hold the results of previous calculations in working memory while they work on the next stage in the calculation. For example, if someone asked us to multiply 6 times 4, and then subtract 10 and add 3, at each stage when we calculated an answer, that preliminary number would be stored in our working memory. In the case above, when we did the first multiplication and got 24 as the answer, we held that number in working memory and then subtracted 10 from it to get 14, which we also held in working memory until we could add 3 to it. In both short-term and working memory, our frontal lobe is the area of the neocortex that is instrumental in making our thoughts stay there long enough for us to function with any degree of certainty.

There is a second type of memory system called implicit or procedural memories. Implicit memories are associated with habits, skills, emotional reactions, reflexes, conditioning, stimulus-response mechanisms, associatively learned memories, and hardwired behaviors that we can demonstrate easily, without much conscious awareness. These are also termed nondeclarative memories, because they are abilities that we do not necessarily need to declare, but that we repeatedly demonstrate without much conscious effort or will. Implicit memories are intimately connected to the abilities that reside at a subconscious level. We’ve done these things so many times, we don’t have to think about them anymore. We use implicit memories all the time, but we do so without being consciously aware of them. Implicit memories are thoughts that not only stay in the brain, but thoughts that stay in the body as well as the brain. In other words, the body has become the mind. Figure 12.1 shows the two different memory systems—explicit and implicit memories—and how they are stored in different regions of the brain.

To better understand implicit memories, think of them as intrinsically linked to our ability to train the body to automatically demonstrate what the mind has learned. Through the mind’s ability to repeat or reproduce an experience at will, the mind has thought about, rehearsed, and planned so well that when the mind instructs the body to perform a task, the body now has an implicit memory of how to do it, and no longer needs the conscious mind. If the body keeps experiencing the same event as a result of the instruction of the mind, the body will become “mindful” enough to be able to naturally produce the action or skill. With implicit memories, the body remembers as well as the mind.

Figure 12.1

The memory systems of the brain.

Athletics abounds with examples of this seemingly automatic functioning. How does a diver go off a ten-meter platform, turn two and one-half somersaults, spring out of that tucked position to complete a series of twists, and then orient the body so that they can enter the water head-first at a close-to-perpendicular position? How much conscious thought can go into a highly sophisticated and technical physical performance that lasts mere seconds? Athletes tell us that they get their minds out of the way and let the body do the work. Similarly, when we learn how to drive a car with a stick shift, after we consciously master the skill, we demonstrate that ability without having to think about each step in the process.

Implicit memories abound in our brain; they are the automatic neural nets that we have developed merely through physical repetition. Brushing our teeth, shaving, riding a bike, tying our shoes, typing, playing a musical instrument, and salsa dancing are all examples of implicit or procedural memories. All these habitual actions take place without too much of our conscious direction.

Remember, these memories did not start out being automatic or implicit. Initially, we had to consciously and repeatedly practice these skills; it took attention and a willful, focused effort to hardwire them. When the mind has repeatedly instructed the body to perform an action, the body will begin to remember the action better than the thinking brain. The mind and the body, both neurologically and chemically, will naturally move into a familiar state of being. Eventually, we can reproduce the same neurological level of mind and internal chemical state of that associated event just by thought alone. Implicit memories ultimately become our subconscious programs.

Once an implicit memory is complete, the body has neurologically memorized the intention of the brain. In addition, the repeated experiences register in the body, and the neurological and chemical signal to the cells is automatically and completely connected to that same level of mind. Intellectual philosophy never makes it to this level in the body because it is devoid of any experience.

As we have learned, consistently repeated experiences write the genetic history of any species. Implicit memories, therefore, are the strongest signals that are genetically passed on, and most certainly, they become the starting point for new generations to follow. When the mind repeatedly unifies with the body, the body encodes what it has learned from the environment.

We learned with episodic memories that knowledge is the forerunner to experience. When we apply knowledge or personalize information, we have to modify our behavior in order to create a new experience. This requires us to consciously apply what we learn not just intellectually (through simple recall) but we must also involve our body in the act of doing. Furthermore, when we use knowledge to initiate a new experience, it is not enough to have the experience only once. We have to be able to repeat that new experience, over and over.

We change explicit memories to implicit memories all the time, and this is the same as making conscious thoughts, subconscious thoughts. When we can do any action without conscious effort, we have formed an implicit memory. Once a memory becomes implicit, any thought to act, or desire to demonstrate what we are thinking, automatically turns the body on to carry out the task, without the conscious mind.

Mastering a language is an example of how we make the transition from explicit to implicit memory. When we are learning a new language, we have to memorize nouns, verbs, adjectives, and prepositions, storing them by association. For instance, we memorize that the Spanish word hombre means man. When we can consciously declare the word hombre every time someone asks us the word for man, the semantic memory of hombre is now stored in the database of our neocortex as an explicit memory. As we learn more words, we store the meaning of each item in the personalized folds of our neocortex.

Next, we listen to our Spanish instructor sing a song about an hombre, and the sensory (auditory) nature of this experience, as well as the Law of Repetition, further wires the meaning of hombre into a long-term memory in our brain. If we progress in our study, we will probably learn most of the Spanish words that are related to various objects, actions, and meanings in our world.

However, this will do us no good unless we put it all together and apply that knowledge by actually speaking the language. As we speak and listen to Spanish in different situations, with diverse people, at different times, and in various places, that system will begin to become implicit. Once we can speak the language fluently, it is wired implicitly. We merely have to think of what we want to say, and the next thing we know, we automatically activate our tongue, teeth, and facial muscles to move in a certain way to produce the right sounds. When we no longer have to consciously think about what language we are speaking, it has become a subconscious, hardwired system.

When people can do something well and we ask them, “How do you do that skill and make it look so easy?” almost all will typically respond, “I don’t know (I cannot declare how I consciously know how I do it); I’ve just practiced so many times that I no longer think about how to do it anymore.” This is the nondeclarative, implicit state—the person has done the action so many times that he or she can do it “un-consciously.” The ability has become so automatic that the body (which is the unconscious mind) takes over.

In contrast to all forms of explicit memories, implicit memories are handled by the cerebellum. If we recall from chapter 4, the cerebellum regulates our body movements, coordinates our actions, and controls many of our subconscious mechanisms. The cerebellum has no conscious centers; it does, however, have memory storage. Its essential purpose is to demonstrate what the brain is thinking: to memorize the plan the neocortex has formulated and put that plan into action without actively involving too much of the neocortex in the operation itself. When we can take knowledge and practice it, coordinate it, memorize it, and integrate it into our body until we can automatically remember it, the cerebellum now has taken on the memory. At this point, the neocortex serves as a kind of messenger, signaling the cerebellum by a thought to start the activity that the cerebellum already knows and remembers.

Ever had the experience of picking up the phone to dial, and you just cannot make the phone number come to your conscious mind? You find yourself staring blankly at the keypad. But then, you think of the person you want to call, and like magic, your fingers push the correct numbers. It was your subconscious mind that stored that information in the form of a procedural memory, and your body knew how to automatically dial the number better than your conscious mind did. When you thought of the person you intended to call, it activated the neural network in your neocortex, which then signaled the cerebellum, and the procedural subconscious memory of the body took over to dial the phone. We can see a similar phenomenon when we ask some people to spell a word for us—often, they can’t do it unless they skywrite it with a finger or actually take pencil to paper. The body remembers better than the mind; the body becomes the mind.

Remember back to your high school locker, and being so proficient at spinning the dial on your combination lock that your hand automatically performed the left-right-left number sequence without the brain’s intervention? Your neocortex was involved in the original memorization of the combination, but in time your body took over, thanks to the coordination of the cerebellum. Since the primitive cerebellum houses no conscious awareness, if someone had asked you how to open your lock, you would have had to stop and call up the instructions from your neocortex. This unity of thinking and doing into a state of being is the hallmark of the cerebellum’s activity.

In fact, studies of archers have shown that when they line up the sight with the center of the bull’s-eye, activity in the neocortex ceases, and there is no thinking; the cerebellum has taken over at that point.1

We enter a trance-like state when the cerebellum has the space and time to remember what it has been conditioned to do, without interference from the neocortex. That’s how we master any action. We rely on the rich dendrite connections of cerebellar memory. Because the cerebellum is responsible for body movements, it is this part of the brain that takes over and runs the show. It is the subconscious mind that now is performing the action, and the seat of the subconscious mind rests in the cerebellum.2

Once an implicit memory is demonstrated and the actions have been easy, routine, natural, and second nature, the neocortex will start the process with a conscious thought, and it is then left to the cerebellum to continue the action. Think of the conscious mind in the neocortex as the system that initiates the subconscious mechanisms driven by the memories and learned abilities in the cerebellum. The conscious mind is the key that starts the engine running. So as the skater turns in preparation to do a triple toe loop, the conscious mind is in charge and is the one that says, “Go!” After that, the conscious mind checks out and lets the body take over. Now the cerebellum gets busy doing its thing, keeping the athlete moving, balanced, and oriented in space during all those jumps, twists, and spins. After years of practice, those systems are now hardwired in the brain and the body.

In truth, when we have used the word hardwired to this point in the book, we were actually talking about the automatic neural nets that are hardwired to the subconscious mind in the cerebellum. The cerebellum functions as the keeper of what the body learns from the mind, while the neocortex stores the mind’s memories.

There are innumerable examples of patients that have amnesia, Alzheimer’s disease, or damage to the hippocampus, who cannot consciously remember their family and friends, and specific things that happen to them on a daily basis. Yet, they still know how to play the piano or knit a scarf. Their ability to retrieve old explicit memories and make new ones has been compromised, but their disease has much less effect on their implicit memories. Their body still knows what their conscious mind in the neocortex has forgotten or cannot learn. It is the brain system below the conscious mind that is executing these tasks.

I know that these additional terms and concepts regarding memory add a greater burden to your understanding. I’d like to simplify some of this for you, and Figure 12.2 should serve as a handy guide as we go along.

First, think of learning knowledge in the form of semantic memory as a way to declare consciously that we have learned that information. When our conscious awareness activates those newly formed circuits in the neocortex, we are reminded of what we learned; we can declare that we know this information, because we have embraced it in the form of a memory. Knowledge involves our “thinking” or our intellect.

We also said that knowledge paves the way for a new experience. To apply knowledge, we have to modify our habitual behavior to create a new experience. Experience, then, is our second type of declarative memory. If learning knowledge is thinking, then having the experience is “doing.”

To firmly establish a long-term memory, whatever we want to remember must have a high emotional quotient, or involve repeated conscious experiences or recitation of an idea. For the most part, though, experiences that we have never embraced before provide just the right newness of cumulative sensory information to create a new flush of chemistry and newly activated circuitry. An increase in the threshold of freshly combined stimuli from seeing, smelling, tasting, hearing, and feeling is almost always a sufficient cue to form long-term memories, because now the body is involved. Doing is what puts the experience into long-term memory.

The first time we have the novel experience of staying up on a surfboard, we can call that “doing it,” and that experience will likely stay with us as a long-term memory. If we can repeat this experience over again at will, now we are “being” a surfer. To make a memory non-declarative, we have to repeatedly reproduce or recreate the same experience over and over until it makes the transition to an implicit system.

In a sense, when we become an expert in any particular area—when we possess a great deal of knowledge about a subject, have received significant instruction in that area, and have had plenty of experiences to provide us with feedback—we move from thinking to doing to being. When we possess sufficient knowledge and experience, when we can recall our short-term and long-term memories to a significant degree and with unconscious ease, then we have progressed to the point of being. This is when we can say “I am”—whether that means, “I am an art historian,” “I am a very patient person,” “I am wealthy,” or “I am a surfer.”

Figure 12.2

Learning knowledge is thinking; applying knowledge is doing and experiencing. Being able to mindfully repeat the experience is the wisdom of being.

When we can make what we have intellectually learned so hardwired that we can easily demonstrate or physically do what we have diligently practiced, we are now procedurally demonstrating what we know. As we possess a memory in implicit form, we are on our way to being a master of that knowledge. In other words, we can demonstrate our knowledge by automatically “being” exactly what we have learned. To learn from our mistakes (or our victories) takes a level of conscious awareness that allows us to willfully make a mental note on what we did to produce that result, and then to become mindful of how we might do it differently or better the next time. Applying what we just learned, we will inevitably manifest a new experience for ourselves. By changing our behavior, we will create a new experience with new emotions, and now we are evolving. Not only do we evolve when we pursue this endeavor, but so does our brain. We will then be using philosophy not only to experience the truth of what we can declare, but to become the living example of that philosophy. Now it is permanently wired in the recesses of our subconscious mind, and it takes no effort at all.

Thinking is what we do when we are using the neocortex to learn. Doing is the act of applying or demonstrating a skill or action, so that we can have a novel experience. Both are part of our explicit declarative memories. Being, on the other hand, means that we have practiced and experienced something so many times now, that it has become a skill, habit, or condition that requires no conscious will to activate. This is the state we strive to achieve with all our actions.

The final stage of learning is produced when we make a conscious effort to unconsciously be exactly what we have learned by the natural effects of repeated experience. If we “have” the knowledge, we can “do” the actions, so that we can “be” whatever it is we are learning. “Being” exists when a skill has become easy, simple, effortless, and natural enough that we can consistently demonstrate what we’ve learned.

As we begin the mindful mental practice of rehearsal, we are declaring who it is we would like to become, and we are attempting to consciously remember that concept of our new personal identity. Mental rehearsal trains the mind to stay conscious of self, and not run rampant to the unconscious programs we have practiced so well. Initially, we have to live in the explicit realm. As we begin to fabricate new circuits and repeatedly create a new level of mind, we are executing will through the frontal lobe.

Mental workouts are a necessity. They are the way we stop the unconscious self from wandering off (“going unconscious”) and becoming distracted by familiar things in our environment, with associations that could cause us to think in terms of the past. In a sense, rehearsal lays down tracks so that the mind has a path for the body to follow. Rehearsal has to be done so well that we can call up this new mind at will. Repetition has to continue, then, so that we repeatedly remember and use that new mind to modify our actions and demonstrate new behaviors and attitudes. Even one experience of applied information will begin cementing knowledge into a deeper meaning.

When we can activate the same level of mind to recreate the desired experience again and again, we are in the final stages of change. By doing, doing, and doing again, we eventually get the body to become the new mind, and the body can take over. Initiating—just by a single thought—the action of who or what we are demonstrating, and letting the body act as the mind’s servant, is how we move to a new self.

Our implicit memories are the consistent demonstration of our explicit memories. In this state of being, we know that we know without thinking. With implicit memories, things become routine, familiar, habitual, and easy. Simply put, we know how—we know what we are doing. At some point we’ve all experienced this sensation of knowingness. It is marked more by an absence of thought than anything else. In a way, it is declaring that we have a nondeclarative system in place. We have trained our body to be one with our mind, and we can call up that memory at will.

To have our actions consistently match our intent is always what separates us from the average in anything we do. Those actions must be implicit in us before we can call ourselves a master of anything. Once we’ve been able to construct an implicit system, we can repeat an automatic action at will and can further refine it at a later time. Keep in mind that in evolving our brain, we are always in the process of moving from explicit into implicit systems, over and over again. We are constantly moving back and forth from conscious awareness to unconscious.

If we were to consciously self-reflect about some unwanted attitude, we would be observing the nondeclarative habits and behaviors that we unconsciously demonstrate on a daily basis. This process takes what is nondeclarative and makes it declarative. We now can see and know who we were being. We can say, “I am a victim. I am a complainer. I am an angry person. I am addicted to unworthiness.” Once we consciously know this (we declared it), we can now reshape a new way of being, by asking ourselves those important questions we discussed earlier, on who we want to be.

As we build a new model of self by remembering who we consciously want to become, we can use mental rehearsal to build the circuits to facilitate a new level of mind. Our mental practice is declaring whom we are consciously choosing to become, by remembering how we want to be. This prepares us to consciously act equal to our intention. As we begin to alter our behavior, we demonstrate a new way of being that will produce a new conscious experience. When we are able to repeatedly demonstrate that experience at will, it becomes a hardwired, nondeclarative memory. After we have arrived at this subconscious state of being, nothing in our environment should cause us to fall prey to our past attitudes. We are truly changed.

I am certainly not saying that change will be easy. Consider that when we have implicitly memorized being a hateful, angry, jealous, or judgmental individual, mentally rehearsing it on a daily basis and physically demonstrating it at will, moment by moment, making it look natural, automatic, and effortless, we are physically and mentally coherent to that attitude. We have trained the body and the mind to work together. So when we want to change to a new state of being, we may consciously like to think that we are sincere and willful. But in the moments of true challenge, it is the body that is directing the affairs of the mind, and most of the time, it wins. This is why we cannot change so readily—the conscious mind and the body are at odds.

Then again, if we have mentally rehearsed and physically demonstrated joy on a daily basis, the same science holds true. In difficult circumstances in our life, if we are wired to be joyful, the environment cannot change how we are.

We should always be evolving ourselves and our actions. When we self-reflect, self-observe, and ask ourselves how we can do something better to refine our skills, actions, and attitudes, we are affirming that we are a work in progress. To self-correct on a regular basis is to observe our automatic thoughts, unconscious actions, and routine habits. Once we declare them as a part of us, we can begin to add a new way of being into the equation of our internal model, during rehearsal. Our ability to change is no different from the people who were able to achieve a spontaneous remission from disease. Everyone has the same frontal lobe capability. We can all ask the what-if questions, formulate an idealized model of ourselves, and prove to ourselves that we can achieve what we set our mind on.

Why, then, is it so hard to change? Because the body has remembered a repeated action so well that it is in charge, rather than the mind. Remember, implicit memories are hardwired programs that require little or no conscious effort. The body holds the reins on the mind, determining most of our unconscious, hardwired actions. Everyone has had a conscious intention to change a habit, and then, so quickly, a sort of mental amnesia sets in and we “go unconscious,” finding ourselves in the realm of the familiar. We fall back into our mental wheelchairs and behave just as we swore we never would. Imagine what it takes to break the habit of being ourselves, by monitoring our thinking processes that result in depression, anxiety, judgment, frustration, or unworthiness. We start out with good intentions and clear resolutions, but our unconscious mind begins to override our conscious thoughts, and in moments, we are asleep at the wheel of our old self once again.

The familiar is so seductive. Whether we are drawn back into unconscious programs by some thought sent from our body due to its chemical needs, by some random stimulation from something or someone in our environment, or by a hardwired action in anticipation of a future moment based on a memory of the past, we can fall prey to the mental chatter that talks us into the convenience of our identity and its cumulative programs.

Try a simple experiment. Lie or sit with your legs crossed, left over right. With your left foot, draw the infinity sign:. As you are doing that, with your right hand, draw the number 6.

Having trouble? As you can see, even though you had clear intentions and the conscious thought to do these two actions, you probably could not break these two neurological habits. To change any behavior and modify our hardwired actions requires conscious will and consistent mental and physical practice, as well as the ability to interrupt routine actions to override the memory of the body and reform a new set of behaviors. Most people will make one or two attempts in actually trying to accomplish the above feat. The ones who persist and continue with effort and practice will master the act, and like anything we do with consistent frequency, intensity, and duration, we can change the brain neurologically. Once it has been changed, this little trick will look as simple as riding a bike.

As I mentioned above, it is crucial that we not stop at the mental rehearsal stage. We have to move from thinking it, to doing it, to being it. Conveniently, those three stages also have three corresponding steps that are necessary in order to move through that process.

My friend’s coach, the baseball pitcher, who mentally rehearsed against the opposing team’s lineup, learned something each time he went out and actually pitched. He didn’t mindlessly repeat the same sequence of pitches against every hitter, or against every team each time he faced them. In fact, the next time he pitched the team that was his nemesis, he used what he had learned in the previous winning outing against them to formulate a new plan of attack. Knowledge that we pay attention to, we learn.

He also solicited instruction and feedback from his catcher, his own pitching coach, and another pitcher on the team. This process of self-observation and self-awareness falls under the domain of the frontal lobe. By quieting all of the other centers of the brain, the frontal lobe helps to sharpen skills of observation. By self-correcting and learning from our mistakes, we will naturally perform better the next time. This is how we evolve our thoughts, actions, and skills. What is wonderful about going out and demonstrating our skill, or a newly minted aspect of our personality, is that we will receive immediate feedback. If we’re really fortunate, we’ll also receive additional instruction. Receiving feedback and instruction are crucial to the process of evolving ourselves.

Whenever we decide to make a change in our life, learn a new skill, adopt a new attitude, enrich our beliefs, or alter a behavior, we make a conscious choice. Whether this choice completely reflects our innate and altruistic desire to be the best person we can possibly be, or is forced on us by negative circumstances, doesn’t really matter. What matters is that we know that we desire something greater for ourselves.

Most important is the idealized self that we construct. The building blocks of that model consist of information that we gather from a variety of sources, regarding who we want to become, or what we want to change about ourselves. Consider that nothing we’ve learned has come without knowledge as a forerunner and as a fundamental part of that learning. On the simplest level, our personal development has relied on our ability to learn and to gain knowledge. Think of the spectrum of skills and information that we use just to navigate our way through any one day, and then think of that knowledge acquisition from a more long-term perspective, as we’ve developed from an infant into an adult.

No matter whether we are learning how to line dance, shed pounds, become a more cheerful person, overcome insecurity, or cut seconds off a 5K race time, we use a three-step process as the opening moves in our attempt to meet our goals:

1. Knowledge

2. Instruction

3. Feedback

To illustrate how knowledge can personalize and alter an experience, let’s say I showed you a painting of water lilies by Monet. After studying the canvas, you might comment, “This painting is beautiful.” You would have one experience of Monet’s work. What if I then took the painting down and told you the following things about Monet’s life, career, and technique: He liked to capture different types of light with pastel colors. He was particularly interested in morning and evening light and how they looked in nature. Monet hoped to inspire people who experienced his work to look at nature and the world in a new way. He worked diligently at seeing things differently than the common man. Throughout his life, Monet looked to see how all things were connected. He was known to make statements such as, “The wisteria and the bridge are one and the same.” I could also say that as Monet got older, he developed cataracts, which began to diffuse and blur his vision. Since he only painted what he was seeing, those characteristic pixels or impressionistic dots that typified his work were really just the way he was processing sensory information.

Now, imagine that I showed you the same Monet painting a second time. You might see it differently, based on the knowledge you just learned about him. Nothing in your environment would have changed; you’d simply acquired new semantic knowledge, and that knowledge had altered your experience of his painting. You made a few important synaptic connections that modified your personal perception. Because of the interplay between knowledge and experience, it’s likely that you would remember both the semantic knowledge and the episodic memory, and store them in your long-term memory.

This simple example demonstrates how important is our perception of reality. When we are exposed to new information, we accumulate new experiences. They upgrade the neural nets of our brain, and we begin to see/perceive/experience reality differently, because we have made a new level of mind in our brain’s existing hardware.

There’s another point to consider about perception and the role it plays in evolving our brain: perhaps we are missing out on what really exists. Do you remember our earlier description of the wine connoisseur? The same fabulous bottle of wine may be shared by an expert and by a novice. The connoisseur’s more evolved mind with its more enriched circuitry will enable him to enjoy a greater level of reality. We, too, can upgrade our brain, and when we do, we upgrade our experiences, and thus we upgrade our perceptions of our life and reality. Knowledge and its application change us from the inside, and change our world from the outside in.

What we are primarily concerned about now is acquiring new knowledge with a purposeful intent—as a means of evolving our brain and, by extension, our life. We discussed this at length in chapter 11, so we know how important it is to secure a baseline of knowledge that we can expand on. To become a more patient person, for example, we need to think about people who exhibit this quality, read books on the art of acceptance and tolerance, read accounts of people who’ve demonstrated a remarkable ability to endure hardships, and so on. We also have to gather some self-knowledge and observe how we respond in various situations, so that we can compare ourselves to the model we’re creating.

Let’s make this even more concrete. One of the most frequently cited desires for change is to gain self-control in the form of losing weight. The first stage of many weight-loss programs is to have those enrolled gain knowledge about proper nutrition, the caloric values of foods, body mass index, the hypoglycemic index of various foods, portion control, the do’s and don’ts of when and how to eat, and hundreds of other concepts. Many diet programs also recommend that we keep a food diary, noting everything we eat in a day to show ourselves exactly how much we consume. This eye-opening exercise is designed to help us gain self-knowledge. Knowledge allows us to look at who we are being, what we are doing, and how we are thinking, and to compare and make the distinction between that and who we want to become.

After learning different concepts, the next step is that we receive a great deal of instruction from the experts. This can be in meal preparation, balancing our intake of various food groups, exercise routines, and so on. Without this key component of instruction, most diets—or self-improvement plans—will fail. We can seek out knowledge and information on our own. But at some point, our progress slows, and we need assistance from someone with more expertise than we have, to get us to the next level. Instruction, usually from someone who has experienced what we are endeavoring to learn, teaches us how to apply knowledge. Instruction teaches us how to do what we intellectually learned.

For example, I know someone (I’ll call her Melissa) who learned to play the guitar. She was self-taught, and her grasp of strumming, picking, and basic chords was impressive for someone who never took a lesson. Although her initial progress was rapid, the learning curve flattened out. She grew frustrated and a little bored, so she sought out a teacher who could help her to progress at a faster rate than she could have on her own. One of the key ingredients of instruction is that we are given guidelines as to how to reach an intended result, by someone who has mastered a skill to some degree. Instruction is the how-to stage.

As we attain knowledge and receive instruction, getting feedback allows us to know how we are doing. Melissa knew that she was doing some things incorrectly, but it took expert eyes and ears to help her pinpoint her weaknesses and assist her in finding ways to overcome them.

Feedback, in its strictest sense, is a response to an input. Generally, it can be either positive or negative. It answers our “How am I doing?” questions. Sometimes we seek out feedback explicitly by asking that question of others and ourselves, and sometimes, agents in the environment provide feedback without our asking for it. For example, if we are driving erratically, either other driverswill beep their horns at us, or the lights of the police cruiser pulling us over will let us know how we’re performing that task.

Ideally, we have the ability to self-monitor, but that isn’t always the case. As is true of all aspects of human behavior, how we react to feedback varies from person to person. Some people respond more favorably to negative than to positive feedback. I’ve worked with several people who, during informal performance reviews, have stated, “That’s nice of you to compliment me, but I really learn more from criticism than praise. Tell me where I need to improve. I already know what I’m doing well.” Conversely, I’ve worked with individuals who crumbled in the face of criticism and needed to have their negative assessments couched in very soft language. How people respond to the timing of feedback also varies. Some people appreciate receiving immediate feedback; others prefer that it be delayed, so that they are no longer in the heat of the moment. Immediate feedback is often the most beneficial, because the cause-and-effect nature of the input is clearer.

Feedback in any form and from any aspect of our immediate environment should never be taken personally. It simply helps us make the distinction between when we are doing (applying knowledge) something correctly, and when we are not.

One of the chief reasons many diets don’t work is that most people like to receive immediate feedback. In talking about the baseball pitcher, we saw that he received immediate feedback in terms of his performance. For a pitcher, a ball whizzing past his head on a line drive toward center field delivers a pretty clear message: don’t throw that particular pitch, in that particular spot, to that particular hitter, at that particular count again.

For dieters, on the other hand, the feedback mechanism is not as immediate. Many programs include weigh-ins and the measurement of body parts to monitor progress. Perhaps even more important to dieters is recognition from family, friends, and peers: “You look great!” and “Have you been exercising?” or even “Something’s different about you.” That can and often does have an even greater effect than tipping the scales a few pounds less than the previous week.

For any committed person who wants change, feedback can also come in the form of the efforts he or she makes. For example, a person who is altering his lifestyle over time can chart what he should eat daily in proper amounts, along with the exercise he wants to do. By looking at that chart over time, he will see the fruits of his disciplined efforts. The visual feedback of seeing his chart fill up with the records of daily wins will serve as important self-recognition. He is on target by matching his intent with his actions.

Often, we also receive self-feedback from our body, based on our own emotional or physical responses to changes we are making. If we are working to lose weight, and we notice that our respiration rate doesn’t skyrocket when we walk up the two flights of stairs to our office, that internal feedback and sense of “I feel pretty good” serves as a strong motivator.

In an experiment performed at the Department of Neurology at Bellevue Hospital in New York City, researchers created a testing and feedback environment to make the paralyzed limbs of stroke victims work again.3 How is this possible, based on our model of what we know about the brain’s ability to learn and change?

The subjects first learned some important knowledge about what might be possible for stroke patients, and then received specialized instruction. After rehearsing a new plan in their mind, patients were ready for a new experience. Using the frontal lobe, they wired new information in their brain, beginning to cause their neural circuits to organize into corresponding patterns.

Now it was time to practice, to turn their knowledge into experience. The patients began to pay attention to immediate feedback they were receiving, on a monitor that showed their brain-wave activity. In the initial part of the experiment, each subject was asked to focus on moving his or her healthy limb, while observing on the screen a specific pattern of his or her brain activity. After repeating this pattern at will through repetitive practice, in a short amount of time patients could easily reproduce the same mind patterns on the screen by their thoughts alone. Each patient became aware of the automatic, unconscious level of mind that it took to move their healthy limb.

As the experiment progressed, the subjects then concentrated on that healthy pattern—thinking about that pattern and making an intentional decision to move the healthy limb (without actually moving that limb). They eventually learned to transfer the healthy brain pattern to the paralyzed limb. The result was dramatic: the paralyzed limb was able to move again.

Through feedback, patients learned to repeatedly create the same level of mind by causing their brain to fire in the right combination of neural nets in the same sequence and order. And by doing so over and over, that new level of mind became a familiar, routine activity. Each time they recreated the brain pattern on the screen, it became easier, because the feedback they were receiving showed them when they were doing the task or action correctly.

Feedback helps us distinguish between when we are reproducing the right level of mind and when we are not, so that we can navigate our way to a particular end. When, through repeated feedback, these subjects were able to create the “level of mind” of normal, healthy movements, they began at will to transfer that mind, to make their paralyzed limb move just as the healthy one did. It took the same frame of mind for these stroke patients to move their paralyzed limb that it took to move the healthy one, and the body will always follow the mind.

This was one of the first experiments to validate that the mind can influence the body through the proper feedback and instruction.

When we get out in the world and put into practice our new skill, belief, or attitude, we’re taking a necessary step in evolving ourselves. What’s important to note is that when we demonstrate our skills and receive feedback, that feedback supplies more knowledge and instruction that we can use, to refine ourselves and our approach to the goal we’ve set. If we receive great knowledge and expert instruction, and we can properly apply that information to produce action, we should expect to accomplish exactly what we set our mind to do. Until we can repeatedly accomplish that end at will, we need feedback to hone or enhance our actions. To finally achieve our intent is the ultimate feedback that makes the experience complete.

Suppose you’ve decided to reduce your level of anger. You’ve long exhibited a hair-trigger response, and you want to become a more understanding person who doesn’t blow up so easily. So you create a new internal representation of serenity, and undertake a process of mental rehearsal. Each day, you do your mental rehearsal exercise, firing together and wiring together new circuits in your gray matter by remembering and reaffirming whom it is you want to become. You feel you’ve been able to get the frontal lobe to quiet all those other areas of the brain, so that you can plan and focus on your goal. The brain then combines and coordinates different neural nets of philosophy and experience to invent a new model of being. When each mental review session is over, you are in the desired frame of mind.

After a month of following this regimen, you feel it’s time to take this new attitude out for a test drive. So you visit Mom. You and your mother have been at odds in the last few months. She’s had to struggle with some minor health issues, but based on how much she talks about them, you’d think she has only one month to live and is in excruciating pain. Every conversation turns into a recitation about her woes and anxieties. You have tried to be sympathetic, but there’s a limit.

After not seeing Mom for a month, you go to her house for a visit, and it’s a repetition of the same old situation. She doesn’t ask about you, your recent promotion, or anything to do with your family, your siblings, or the rest of the world. In the past, you would call her on her behavior, but this time, you simply sit and listen, nod when appropriate, empathize with her, and then leave after an hour, still on good terms with her. You feel like you’ve done a good job of producing a different result. But on the drive home, you notice that your teeth are clenched and you’re strangling the steering wheel, and when you get home, a splitting headache drives you to bed. How did you really do?

When we set out to demonstrate our new skill or ability, we inevitably rely on the environment to provide clues to how we’re doing. Whether we want it to or not, the feedback from our environment is going to give us a status report. This is fairly simple when it comes to improving a physical skill. I knew, based on the number of times I fell, felt out of control, or didn’t cut a turn as sharply as I wanted to, how I was doing when I first learned snowboarding. If the number of words we type per minute increases, we know we’re moving toward a higher level of proficiency. But what if we’re trying to be less prone to displays of anger?

When our goal is to change an unwanted neural habit, replace it with a new level of mind, and then demonstrate our new attitude automatically and naturally, if our demonstration (external feedback) does not match the internal state of our body, we are still not there yet.

In our example, even though you demonstrated patience and control in being with your mother, you still left the scene in a suppressed state of rage and frustration. In your mental rehearsal you had practiced being not angry, but compassionate. By visiting Mom, you received some good feedback that you can work with, because you controlled your impulses; however, you did not complete your intended desire. Your internal state did not match your external demonstration and, therefore, you were not “being” compassionate. When the demonstration of our modified actions produces the desired external feedback, and our internal state matches that intent, we are controlling the mind and the body, both neurologically and chemically.

How can we accurately assess our new level of mind? We must self-reflect to examine whether what we are doing is congruent with how we are feeling. If it is not, then we must insert a new plan in our mental rehearsal so that the next time, we improve both our actions and our feelings.

When we make anything implicit—driving a stick shift, knitting, buttoning our shirt, playing the martyr—we do these things without the intervention of the conscious mind. We have wired those circuits to the cerebellum, and both the brain and the body have these tasks memorized almost like blinking, breathing, repairing cells, and secreting digestive enzymes.

Once we have a conscious thought in our neocortex, an unconscious thought/associative memory/implicit memory fires in response to our environment, and causes us to think equal to this stimulus. This process is often referred to as priming: we have an unconscious response to an external source that makes us think and act in a certain way, without even being conscious of why we are doing it. Priming finds its origins in the nondeclarative memory system.

Have you ever noticed that if you think about flowers and recall the image of a rose, the other flowers you have stored in your brain are likely to fire as well? That’s an example of priming. Psychologists use the term priming because of its relation to the priming of a pump. To get a pump system to function properly, a liquid must already be present in the system in order to get the pump to draw more liquids out.

In neurological terms, priming involves the activation of clusters of neural nets that are surrounded by, and connected to, other clusters of nets holding similar concepts. When one cluster is activated, those other nets connected to it will be more likely to come into consciousness. Priming can also refer to a phenomenon that we’ve all experienced: once we buy a new car, say a Nissan Sentra, we begin to notice many more Sentras on the road than we did before. Because of our exposure to one event or experience, we’re more acutely aware of other, related stimuli.

With priming, a brief, imperceptible stimulus provides enough activation for a schema (a mental structure of some aspect of the world) to be rolled out. Schemas enable us to function in the world without necessitating purposeful thought. For example, we have a schema for a door, so that no matter what kind of door we encounter, we negotiate it.

Unfortunately, we also have schemas that are stereotypes, scripts, or even worldviews to help us understand the world. That is why we may have unconscious, reflexive responses to happenings in our environment. Many African-American males, for example, report that when they enter an elevator with Caucasians, they notice that the women will clutch their purses more tightly, and men and women will both edge farther away.4 If we were to ask Caucasians why they exhibit these behaviors, they are either unlikely to recall having done so, or claim that it meant nothing—it was simply a habit. Priming is an implicit reaction that happens beyond our conscious awareness.

Along with this kind of response to stereotypes, we exhibit a host of other behaviors that are implicit, hardwired body memories, which have either been conditioned as a part of our genetic inheritance, or that we have taught the body to do automatically through repetition. For example, our environment constantly triggers implicit responses. Why is it that we can be having a pleasant day, and then, inexplicably, one irritant (a neighbor’s son drives by with a thudding sound system in his car) sets off a cascade effect of mood-dampening responses? We immediately recall the slight irritation we felt when the same neighbor invited nearly everyone else on the block over for a holiday get-together, but didn’t invite us. Then, anger swells as the vision of our mailbox dangling from its post, the clear victim of a baseball bat attack, rises before our eyes. Suddenly, we’re running all the programs in our head that tell us how much people disrespect us. That nice day turns dark, and we can’t explain why, because so much of this has been an unconscious, reflexive response.

These functions that produce what we commonly refer to as our mood are part of our limbic system, which acts as a kind of subconscious thermostat. Because these are also subconscious systems, the body will follow the command of the brain, because that is what we have trained it to do so well. It doesn’t ask questions like, Are you sure, boss? It just takes orders and follows through on the commands of the mind. The more unconscious our thoughts are, the more we are allowing the body to be in command. This is why it takes conscious awareness to stop the process.

How much of our day is about allowing the environment to cause us to think? This is exactly what priming is. When we allow the environment to rule our thoughts, it turns on all the implicit, associative memories we have hardwired, and we are then running programs—unconscious streams of consciousness—with no conscious awareness. This means we are unconscious most of our waking day. We are “being” our familiar memories that we have wired from so many unconscious habits. If we are not getting the chemicals we have become accustomed to, a voice from our past begins to fire in our brain. Once we have that thought (which is a result of our chemically addicted body screaming back to the brain that it needs a fix), the corresponding neural network will fire. The next thing we know, we are unconscious and acting without thinking, creating states of anger, depression, hate, and insecurity.

In what may be an example of priming, several studies suggest a link between acts of homicide in school settings and continuous exposure to violent video games. Although this is difficult to prove, such games, along with many other factors, may contribute to priming certain at-risk youths to commit violent actions, in what could well be unconscious demonstrations of aggression.5

Advertising is a key priming mechanism. Sometimes an unconscious thought triggers a circuit that fires as a result of the numerous, repetitive television commercials we see. We tune into mental programs that highlight sickness, or feelings of being deprived, or a separation from self. As a result of the “mental rehearsal” of seeing so much advertising, and having practiced these feelings mentally and instructed our body on how to demonstrate them so well, the next thing we know, we think we need a new prescription drug for a syndrome we’re now sure we have, or we feel that our old car is now inadequate, and we have to replace it. All this happens without much conscious thought. We all unconsciously respond to cues in our world, matching our own social and personal limitations. Are we really freewilled?

What’s so remarkable is that we allow this process of creating unconscious conditioning to produce the current (and perhaps, sad) state of our existence. When we are living from our past unconscious memories, we are priming what is familiar in us. In truth, the more routine we are, the more controlled we are by the environment, our associative memories, and our unconscious social beliefs. To be primed is to be unconsciously controlled by the external world, and we behave accordingly.

A break in our routine—whether a two-week trip or another alteration of our daily life—can sometimes prompt this type of perspective shift. Most people who go on vacation will vouch that by being out of their environment, they can get a greater sense of perspective. Mental rehearsal is another type of escape from the enslavement of environmental priming. Going within to rehearse provides us with the type of perspective alteration that is a necessary precursor of truly evolving our brain and behavior. When we rehearse long enough, we will produce a deeper change that occurs at a deeper level of consciousness.

Just as priming allows us to notice more cars like the one we recently purchased, if we focus on becoming a more grateful person in our mental rehearsal, we will not only realize more things that we have to be grateful for, but we will also witness more acts of gratitude that we can assimilate into our ideal. When we change our implicit perception from a negative one (the world is inherently unfair) to a better one (I deserve good things and I have them all around me), we go from seeing things unconsciously, based on past memories and experiences, to seeing things consciously. When we consciously choose to focus our attention on exploring more evolved virtues, we have gone from an implicit, unconscious view of the world to an explicit perception. As we practice this new attitude consistently, we will change this new state of mind into an implicit memory.

We can use this concept of an unconscious cue triggering our implicit system to our advantage. Mental rehearsal serves as a self-priming mechanism. If, for instance, we work on creating a model of ourselves as a restrained and patient person, then as we sit in solitude, that concept of ourselves becomes more real than anything in our environment. Thus time and space recede, and our past identity and experiences as an angry, impatient person also recede. If that thought of the new version of our self becomes real to us, then we have primed ourselves for another, more positive kind of cascade effect. We have primed ourselves to be tolerant, instead of the environment causing us to think and act with unconscious neural habits. Because priming activates circuits that cause us to behave in certain ways, we can prime our brain to function equal to a focused ideal. Instead of spiraling downward, we can rise upward. In this way, we demonstrate that it is possible to change, that we can disconnect ourselves from the environment and the collective influences that have shaped us. When we mentally rehearse, we are priming the brain to help us be at cause in the environment, instead of feeling the effects of it. Self-priming allows us to be greater than the environment. And being greater than the environment is what evolution is all about.

Let’s go back to the example of the booming car stereo triggering our internal war with the neighbors. Our perception of the events themselves could be altered, if we had been doing the kind of mental rehearsal we’ve discussed, and had trained our frontal lobe to still the emotional centers that (in our example) run riot in our brain. Instead of thinking, “That damn kid drives up and down the street just to piss me off,” we would either ignore the sensory input entirely or think, “Mark must be on his way to work.” Instead of thinking, “They took out my mailbox. Everyone’s out to get me,” we would think instead, “Random acts of stupidity and violence are everywhere. I should be grateful it wasn’t worse.” That shift in perception will start out as explicit and ultimately become implicit.

In reality, we have been mentally rehearsing those negative states of being and demonstrating them our entire life. Our unconscious thoughts and behaviors dictate what we believe and how we behave. Why is it that we can focus on one little irritant of a stimulus to the point that we create an entire web of unhappiness, frustration, and anxiety? We can be in the grocery store, and just as we are approaching the shortest line, the clerk says that the person just in front of us will be the last one he will check out. Every other line is jammed with people. We have only 15 items, and we’re in the express lane. It’s clear that the person in front of us is well over the limit. There’s that conspiracy again—those who play by the rules get screwed in the end. And now, because of the jerk in front of us, and the miserable clerk who probably can’t count to 15, we’re going to have to get into one of those other lines and wait. The litany could go on, and it does, in our head. As the old adage goes, reality is eleven-tenths perception … and somehow the mind seems to be a factor in influencing it.

What we may fail to understand is that the brain doesn’t discriminate among thoughts on the neurological level. It takes no more effort to form a positive thought than it does a negative one. Attitudes are simply accumulations of related neural nets, and positive attitudes are as easy to construct as negative ones. (I use the terms positive and negative to demonstrate actions, behaviors, attitudes, and thoughts that serve us and don’t serve us.) Yet, few people construct those positive ones. Few people arrive at the conclusion that just as we can develop the habit of being depressed, angry, sullen, suffering, or hateful, we can be happy, content, joyful, and fulfilled. We take the negative states of mind that we’ve inherited from our parents and other ancestors, and we reproduce them. We then reinforce those states of mind, based on our own prior experiences.

Scientific evidence shows that the brain is as changeable as the words we write in our word processing program. The irony of this is that the way out of the mess we’ve created requires us to use the same tools we used to get ourselves into it. We don’t need a simple twist of fate to write a happy ending to our own life story; considering things from a slightly different perspective may be all that’s required.

All we can ever know is based on what we perceive. What we perceive is based on what we experience, along with the tools of interpretation we inherited and employ, time and time again. Do we perceive the world as a place filled with negativity, because we have trained ourselves to look for it and ultimately be its reflection? Colin Blakemore and Grant Cooper at the Cambridge Psychology Laboratory conducted an experiment on cats that sheds some light on this question of how and what we perceive.6 The researchers placed kittens in two groups. The first group was raised in a chamber lined with horizontal stripes. The second group was raised in a chamber lined with vertical stripes. Because the kittens were placed in their environment at a critical time in the development of their sensory apparatus, and because they were exposed to only one type of line, their visual receptors were limited. The so-called “horizontal cats” were unable to perceive vertical objects. When a chair was placed in their environment, the cats walked right into the legs as though they weren’t even there. The so-called “vertical cats” could not perceive horizontal objects, so when they were placed in an environment with a tabletop, they would either avoid going on it, or they simply walked off its edge. All the objects in the cats’ reality already existed, but they could not see them. The lesson here is that we are able to perceive only what our brain is organized to tell us.

Could it be, for example, that our brain is organized to perceive injustices directed against us? Might this have happened because we inherited from our parents, and then heard while growing up, constant reinforcement of the idea of persecution and incessant replays of life’s unfair events? If so, then we aren’t able to perceive the opposite situation. We lack the receptors for fairness, and no matter what we do, we won’t perceive a situation as anything but unfair. Clearly, how we perceive and respond to the environment is intrinsically linked to our habits of being and our state of mind on a most nondeclarative level.

Not everyone gives in to self-imposed or inner-directed perceptual biases. We saw this illustrated clearly in chapter 2 with people who experienced healing from disease. As we recall, the prognosis for most of them was not good. They could have retreated and run all the programs that were hardwired in their brain, but instead, they chose to believe a different set of truths than most people would in their situation. For example, they believed that an innate intelligence inhabited their body, giving them life and possessing the power to heal them. Along with that conviction, they held firm to the notion that our thoughts are real and can have a direct effect on our body. They also held that we all have the power to reinvent ourselves. In the process of inward attention, they experienced the ability to focus so intently that time and space seemed to disappear. As a result, they were able to employ their mind in doing work very similar to what I’ve described as mental rehearsal. They used knowledge, instruction, and feedback to affect cures on a wide variety of conditions and diseases. They constructed a paradigm of themselves as healthy, and they held that idealized image in their frontal lobes with an intensity of concentration that literally cured them.

We spoke extensively about change in the previous chapter, and this model should help you to understand how change is possible. To change is to have a new mind in spite of the body and the environment, and to train the body to follow in that new direction. When the body has become trained by our repetitive actions and experiences to be the mind, it will take all of our conscious will to stop the body’s conditioned mind from controlling us. To change is to break the physical and mental conditioning of being ourselves—that is, what we repeatedly think and do. If we can modify our regular, normal, unconscious daily actions enough times by using our conscious mind, we will redirect the body toward a new experience of ourselves and our reality. When we learn something new and want to apply it, we must take control of the habitual actions of the body’s mind, and use the conscious mind as a compass. With the proper knowledge, instruction, and feedback, we can replace those old patterns of thinking, doing, and being with new ones, and evolve our brain through new synaptic connections and rewired neural networks. Then the same subconscious mind that is keeping our heart beating will navigate us to a new future.

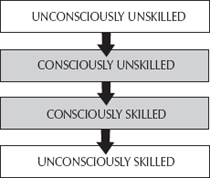

When we are learning anything new and taking it to a level of skill and mastery, we follow four basic steps.

1. First, we start out unconsciously unskilled. We do not even know that we don’t even know.

2. As we learn and become aware of what we want, we become consciously unskilled.

3. As we begin to initiate the process of demonstration (the “doing”), if we keep applying what we learn, we eventually become consciously skilled. In other words, we can perform an action with a certain amount of conscious effort.

4. If we go further, continuously putting our conscious awareness on what we are demonstrating, and we are successful in performing the action repeatedly, we become unconsciously skilled. When we begin the process of change, this is where we want to end. Take a look at Figure 12.3 to examine the flow chart of skill development.

I briefly mentioned snowboarding earlier when I was describing learning a new skill. A few years ago, I decided to learn to snowboard. I was unconsciously unskilled. Once I decided that I wanted to learn how to do this new thing, I crossed into the territory of being consciously unskilled. I knew that I didn’t know how to snowboard. Through the process of instruction, in which I gained knowledge about the how-to’s of snowboarding, and put that knowledge to use when I practiced the activity, I made the transition to being consciously skilled. I was able to perform the skill with conscious awareness—in other words, I had to think about what I was doing nearly every second in order to remain upright, pointed downhill, and in control. I had to be consciously present every second with my intent, and when I lost my concentration, the result was pretty painful. With any skill we learn, this formula applies—whether it is a sport, an attitude, a virtue, or a supernatural feat. To master anything is to make it an implicit memory and make it look easy.

In time, with more practice, and fewer falls, I could make it down the hill without having to remind myself of every bit of instruction I’d learned about how to snowboard. Then my body had to relax enough to make snowboarding second nature without too much exertion. I began to think less, and let my body remember what to do. Once I got to the point when I didn’t have to think about what I was doing and was able to just do it, I was now at the stage of being unconsciously skilled.

As I was researching this book, one of the people I interviewed told me that he had suffered from debilitating depressive episodes from his adolescence through his late twenties. This surprised me, because upbeat, compassionate, and spontaneous Larry seemed like the last person in the world who would have a history of depression.

Like many functionally depressed people, he was a good actor: most of his colleagues at the design firm where he worked would have never guessed Larry harbored a secret. He often stayed late on the pretext of having to work, but in reality, he feared going home to an empty apartment.

During weekends, Larry purposefully avoided most human contact, because routine social exchanges were a reminder that he lacked meaningful and emotionally intimate relationships. Thus, he had become a member of what he called the Dawn Patrol. On Sunday morning, he’d arise before 6 a.m. to do his weekly marketing. He’d developed the habit because, following the painful dissolution of the one long-term relationship he’d had, he’d be in tears as he walked the grocery aisles, plagued by memories of the two of them shopping together. After a failed marriage, he went into a tailspin, ultimately not showing up for work and lying in bed, his apartment strewn with garbage. After that, a psychiatrist diagnosed his problem and suggested antidepressants. Larry declined.

Just a few months after his diagnosis, he was feeling as good as he ever had in his whole life. He told me that when he discovered that what was causing his oddly morose behavior was biochemical in nature and not some parental curse (his parents were undiagnosed depressive recluses who remained emotionally distant from Larry and his siblings), he felt enormous relief. Once he could apply a label to the disorder in his life, he could formulate a plan to overcome it.

Larry applied some mental discipline to his personal transformation. He read up on depression and its causes and cures. He even dabbled in some self-help reading. But instead of imagining how he could regulate the action of his serotonin uptake inhibitors, he started thinking about who he wanted to be. He created a mental catalogue of the circumstances and events from his past and from his observation that he could label as “happy.” Larry then created an ideal of what he wanted his life and his personality to be like.

It was easy to find inspiration for this “creature” he was “Frankensteining” together. He’d spent the better part of his life admiring the ease with which other people seemed to move through their days and engage in social activities. From one person, he “stole” a sense of humor; from another, a social adroitness that manifested in always being able to say the right thing; and from another, a self-confidence that never veered into cockiness. When he’d assembled parts from donors real and imagined (he did a lot of “homework” watching television and movies, imagining how the newly configured Larry would behave), he speculated about how that conglomeration of parts would make up his new personality.

Larry inserted himself mentally into situations, real and imagined, to practice the behaviors that he would have to change. He already had a strong set of skills; his professional life was a good platform from which to build. That Larry hadn’t been able to transfer those skills to his social life was one of the major symptoms of his particular form of depression. He saw that there were two different Larrys. For a long time he had to ask himself in social situations, “WWWLD?” (What Would Work Larry Do?)

After he’d assembled all that knowledge, much of it semantic, he set out to demonstrate what he’d learned and mentally rehearsed. Intuitively, Larry understood that he had to change some of his habitual actions. One of the first things Larry did in his quest for change was to force himself to go shopping after work or in the middle of the day on Saturday. Larry also practiced being “happy” on the weekends. In time, he was able to leave his apartment anytime he wanted, or whenever he felt himself sliding too comfortably into his old routine. Eventually, when he went to the grocery store or for a run or a bike ride around the neighborhood, he noticed that people would smile at him, and he could smile back.

In addition to taking up karate, Larry challenged himself by taking classes at a local improv theater. He had no intention of ever performing—although the last class project was to participate in a show—but he wanted to be able to think more quickly on his feet. At first, he responded more in his head than aloud during classes and exercises, but his confidence blossomed, and he emerged from his shell in surprising ways. Larry understood the implications of his on-stage transformations.

Over time, Larry was able to stop asking himself, “WWWLD?” When he applied some of those social skills to his personal life, people responded to him. Once those new circuits were more firmly wired, once he was out in the world practicing being more open and exposing himself to new experiences, he eventually got to the point where Work Larry and Home Larry were just Larry. Being this new, modified, version of himself was becoming easy.

Eventually, Larry even started to date Rebecca, a brown belt in his karate class and an intensely vivacious woman any man would be attracted to. Her presence provided a whole new set of emotional experiences that he loved and enjoyed.