Global supply chains and U.S. national security

by Jonathan Chanis

JONATHAN CHANIS has worked in investment management, emerging markets finance, and commodities trading for over 25 years. Currently he manages New Tide Asset Management, a company focused on global and resource trading. He previously worked at Citigroup and Caxton Associates where he traded energy and emerging market equities, and commodities and currencies. He has taught graduate and undergraduate courses on political economy, public policy, international politics, energy security and other subjects at several higher education institutions including Columbia University.

! Before you read, download the companion Glossary that includes definitions, a guide to acronyms and abbreviations used in the article, and other material. Go to www.fpa.org/great_decisions and select a topic in the Resources section. (Top right)

Amid the coronavirus outbreak an employee works on the production line of surgical masks at Yilong Medical Instruments Co., Ltd, on April 16, 2020, in Zunyi, Guizhou Province of China. (QU HONGLUN/CHINA NEWS SERVICE/GETTY IMAGES)

The Covid-19 pandemic has painfully reminded Americans that their access to vital medical supplies depends on foreign, especially Chinese, manufacturers. Critical provisions including facemasks, gloves, gowns, ventilators, and generic pharmaceutical drugs such as antibiotics were in desperately short supply. U.S. manufacturers were unable to increase production and compensate for foreign supplies that stopped arriving, or satisfy the surge in demand due to the higher Covid-19 case load.

The lack of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and other supplies revealed a strategic vulnerability in America’s medical supply chain. The intentional withholding by China of products previously shipped to the U.S. illustrated not only the extent of this vulnerability, but also how foreign governments manipulate these vulnerabilities. It is this foreign government manipulation that primarily distinguishes a strategic supply chain vulnerability from a commercial vulnerability. Commercial vulnerabilities tend not to occur through government actions, and their purpose tends to be profit oriented, not political.

The U.S. medical supply chain struggle with China and a few other states is part of a larger conflict involving many other supply chains across a range of products and sectors. These include defense-related products, semiconductors and computers, telecommunications and aerospace equipment, passenger railcars, and automobiles. From a national security perspective, there are several relevant aspects to global supply chain (GSC) vulnerability:

1. The transformation of the supply chain over the last 30 years led to the relative deindustrialization of America, particularly in comparison to China. The U.S. produces fewer defense products, weakening its defense industrial base (DIB), and the U.S. military and government struggle to purchase a range of civilian products. Continued relative deindustrialization also, by definition, undermines the U.S. non-defense manufacturing sector’s ability to innovate and develop emerging products and technologies.

2. As China sells more products to U.S. consumers and the U.S. military, the nation becomes more vulnerable to espionage, economic and military sabotage, and large-scale data thefts or misuse.

3. A range of economic policy options targeting GSC vulnerability can be deployed for undermining national adversaries.

At least three policy options for dealing with GSC vulnerability have emerged; they are: renewed engagement, decouplement, and industrial policy adoption. How the U.S. attempts to reconfigure the GSC to minimize its strategic vulnerability or maximize that of other countries raises fundamental questions about the use of economics as an instrument of international power. It also raises sensitive questions about the relationship between the U.S. government and the private sector. Decisions about strategic GSC vulnerability will profoundly affect U.S. economic security, U.S.-China relations, and the overall standing of the U.S. in the world.

Economics as an instrument of power

U.S.-China tension over GSCs is a manifestation of an intensifying power conflict caused by China’s rise over the last 20 years. China’s 2001 World Trade Organization (WTO) entry allowed it to transform its economy by increasing inbound direct foreign investment and the outbound sale of manufactured goods. This economic transformation then financed China’s substantial and continuing military modernization, and allowed it to create webs of economic dependencies throughout the world. Such a radical transformation in the global balance of power can only alarm the U.S., if it wishes to avoid Asia being dominated by China.

As China’s ambitions increase and the rivalry with the U.S. intensifies over issues such as China’s actions in the South China Sea, takeover of Hong Kong and designs on Taiwan, it becomes extremely difficult for this struggle to avoid pushing the economic relationship from cooperation to competition. Economic power, like military, diplomatic, or cultural power, is just another instrument used by states in their competition to survive.

While much attention focuses on the U.S. use of economic power, China also uses its growing economic might to damage other states when it feels its interests challenged. Among countries targeted since 2010 were Australia, Japan, Norway, the Philippines, and South Korea, and the goods and services utilized included agricultural products, fish, entrainment programing, tourism, and rare earth metals. The pretext for these actions ranged from displeasure over military deployments and territorial claims, to human rights criticism and a request for an investigation into the origin of the coronavirus.

The difficulty with using economics as an element of power in the U.S.-China relationship is that globalization and the growth of GSCs has knitted the two economies together in ways that are costly for either side to undo. Moreover, some sections of the American elite still think China is either not a threat to the U.S., or that it can be brought into a new American-managed international economic order on terms advantageous to the U.S.

The ability of the U.S. to utilize effectively economic power against China depends on: finding a durable domestic consensus on the nature and scope of China’s challenge to U.S. interests; the costs it is willing to bear to use economic power; and how well it can control the actions of its own and other countries’ multinational corporations (MNCs).

Global supply chain basics

A supply chain describes the steps necessary to bring a product or service to a customer, and it usually includes procuring raw materials, transforming these materials first into intermediate goods and then a final product, and then selling and delivering the finished product to a customer. Supply chains coordinate the actions of multiple companies and industries, and when these actions cross national borders they are global. The chain metaphor is useful because the entire operation is only as strong as its weakest link.

Between each step in a supply chain, many activities occur including: defining all concerned parties’ expectations of others through documentation, contracts, and information exchanges; physically moving intermediate and final goods between locations or organizations; and storing goods until needed. Logistics refers to the latter two activities of moving and storing goods, and its purpose is to ensure that there are no delays between steps and that costs are minimized.

In the production of a good or service, innumerable events can disrupt the process and threaten sales and profits. “Just-in-time” inventory management increases supply chain vulnerability by reducing inventory along the chain. Increasing complexity also makes current GSCs more fragile since there are often multiple supplier levels, many of whom are unknown to the organizing company. Given the tendency for single product suppliers, there also often are many “single points of failure.” Consequently, if a particular item is delayed or fails to arrive, the entire production process may stop. The high and increasing dependence of GSCs on information technology also places them at greater risk since they are more easily disrupted by competitors, cybercriminals, random malicious actors, and even foreign governments. Global supply chains are an essential feature of contemporary business strategies to maximize corporate profits. Poor supply chain management can result in higher material and labor costs, expensive delays, manufacturing quality problems, missed sales, and ultimately lower profits or even losses. Improving supply management can represent small but repeated advancements that cumulatively, by making the production and sales process ever more efficient, contribute mightily over the long run to corporate profits.

Chinese factory workers assemble motorcycles on the assembly line at the plant of Sundiro Honda Motorcycle Co., Ltd. in Taicang City, China. (CYNTHIA LEE/ALAMY)

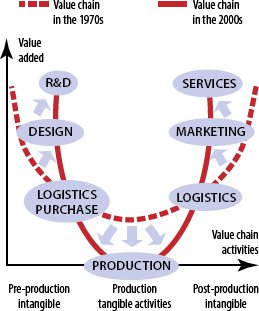

Chart 1

A TYPICAL SUPPLY CHAIN

LUCIDITY INFORMATION DESIGN, LLC

The phenomenal change to the global supply chain since the 1990s reflects both the search by MNCs for greater profitability and China’s opening to the world. Major improvements in information and communication technology (ICT) in the 1980s and 1990s allowed MNCs to move production elsewhere. China, with its extremely low-cost labor force and improving infrastructure, provided the ideal ground for a factory location. As a result, hundreds of thousands of manufacturing operations were established in China. This “offshoring” of production was accompanied by “outsourcing” whereby corporations shed entire parts of the production process and began purchasing components or products from others. MNCs were central to manufacturing relocation because they provided or facilitated vast flows of foreign direct investment for financing these factories.

The increased share of intellectual property contained in manufactured products also accelerated the shift toward outsourcing, since manufacturing itself usually is not highly profitable. Apple is the quintessential example of this. While over 3 million people now work in Apple’s China supply chain, only 13,600 people were reported in 2018 to be directly employed by Apple. The actual manufacturing of an iPhone, for example, is primarily handled by Foxconn of Taiwan.

iPhones illustrate how a disproportionate part of a product’s profitability often comes upstream from manufacturing, from research, development, and design, and downstream, from marketing, sales and service. This was first described by Acer’s co-founder Stan Shih in 1994 as the “Smile Curve.” The assembly and manufacture of most goods tend to be a low profit margin business, and most U.S., European and Japanese corporations were eager to have foreign companies take over this part of the process. This also exemplifies the MNC’s greater concern for the “value chain,” rather than the supply chain. The former focuses more on where in the process a company makes its money; the latter focuses more on how and where it physically makes its products.

As Chart 2 shows, the profitability of the upstream and downstream parts of the GSC increased substantially after the 1970s with offshoring and outsourcing. As global corporations got better at shifting low profitability, midstream work to foreign manufacturers, they became even more profitable.

Chinese supply chain dominance

The relocation of so many manufacturing facilities out of the U.S., Europe, and Japan completely reconfigured global supply chains. This reconfiguration made China not only the assembly and manufacturing workshop of the world, but also a manufacturing superpower. If one excludes North American automobile manufacturing, China basically dominates the global manufacturing supply chain.

Chart 2

THE SMILE CURVE

Value distribution along the global value chain

SOURCE: “INTERCONNECTED ECONOMIES BENEFITING FROM GLOBAL VALUE CHAINS”, OECD 2013.

According to a study by BCG, China produced more real manufacturing value in 2017 than the U.S., Germany, South Korea, and the UK combined. It dominates vast global industries such as: textiles and apparel; furniture and bedding; toys and sports equipment; active pharmaceutical ingredients for generic drugs; optical instruments; machine tool building; ship building; electronic equipment including flat-panel display manufacturing; computer and other media device assembly, and; telecommunications equipment including phone manufacturing and assembly.

A number of economists, including Arvind Subramanian and Martin Kessler at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), label China’s rise to supply chain dominance between the 1990s and 2008 as a period of “hyperglobalization.” Compared to previous globalization experiences, the growth in global trade since the 1990s vastly outpaced the growth in global (or U.S.) Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This super-sized international trade growth made it impossible for most all developed countries, including the U.S., to adapt to the surge of manufactured goods coming out of China. As a result, entire American industries, including furniture and bedding, toys and sports equipment, apparel and shoes, and a range of light manufacturing products such as televisions and washing machines were just destroyed by Chinese imports.

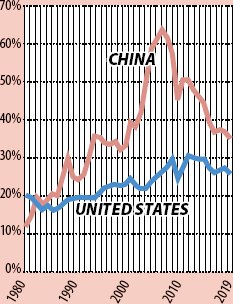

Subramanian and Kessler also labeled China a “mega-trader” in order to differentiate it from all other contemporary countries since its export capacity relative both to its own and the global economy were so immense. As a share of its GDP, China’s exports are almost 50%, and at its peak year 2008, China’s trade-to-GDP ratio, i.e., imports and exports of goods and services, was 62.2%. (See Graph 1.) No country including the U.S., Japan, or Singapore at their peaks came close to these figures. The nearest any other country came to this global trade dominance was Britain in the heyday of its empire before World War I.

Graph 1

U.S. AND CHINA TRADE 1980 – 2019 (by % of GDP)

SOURCE: WORLD BANK. WORLD DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS, TRADE AS PERCENT OF GDP. SEP 8, 2020.

Relative deindustrialization

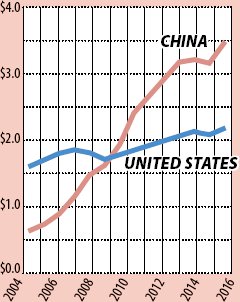

As some point out, the U.S. still is a manufacturing powerhouse, and based on value added in 2017 it manufactured $2.2 trillion of goods. But while the U.S. remains a manufacturing powerhouse, China is a manufacturing superpower. Beginning in 2010, China’s manufacturing output surpassed that of the U.S. and the gap between the two has grown ever since. (See Graph 2.)

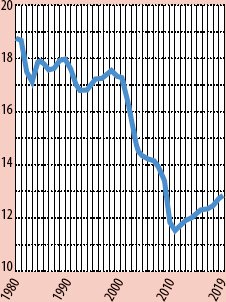

In 2017, China manufactured $3.5 trillion of goods, or almost 60% more than the U.S. As a share of GDP, U.S. manufacturing has been declining for over a decade (see Graph 3), and when properly measured the U.S. in the 2000s lost more manufacturing output as a share of GDP than almost any other developed nation. This decline is starkly evident when comparing the U.S. and China share of global manufacturing output the over time. The U.S. share declined from almost 30% in 2002, to 17% in 2018; China’s share rose from less than 10%, to 28%. According to the U.S. Census’ Statistics of U.S. Businesses, during this time over 60,000 U.S. factories (out of approximately 350,000) closed.

Empirically, there is little doubt that free trade was incredibly beneficial to the U.S. According to a calculation by the Peterson Institute, international trade and investment since 1945 raised real U.S. household incomes by $10,000 annually. But the reality since around the year 2000 gets more complicated, and many ardent, past supporters of free trade including Alan Blinder and Paul Krugman are asking if the unabashed enthusiasm for free trade went too far. In particular, they ponder if there was a connection between decades of increasing China trade with America’s manufacturing decline and the growth of U.S. income inequality.

In its contemporary form, the economic argument for free trade emphasizes that a country is better off with the maximal amount of global specialization and trade because goods and services are produced more efficiently and this lowers prices and increases consumer purchasing power. Employment losses from trade are dismissed as “transition costs” since workers will find other well-paying jobs to replace those lost through imports. Everyone is better off since consumers have lower-priced products and displaced workers are absorbed back into the labor force at sufficiently high incomes.

Graph 2

U.S. AND CHINA MANUFACTURING OUTPUT, 2004 – 2016 (VALUE ADDED IN CURRENT U.S.D. TRILLIONS)

SOURCE: WORLD BANK. WORLD DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS, MANUFACTURING, VALUE ADDED (CURRENT US$). SEP. 8, 2020.

Graph 3

U.S. MANUFACTURING (as a percentage of GDP)

SOURCE: FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST. LOUIS. VALUE ADDED BY PRIVATE INDUSTRIES: MANUFACTURING AS A % OF GDP, PERCENT, ANNUAL, NOT SEASONALLY ADJUSTED. JULY 6, 2020

However, in “The China Shock,” David Autor and his fellow researchers summed up the impact of Chinese exports on the U.S. as follows:

“Alongside the heralded consumer benefits of expanded trade are substantial adjustment costs and distributional consequences. These impacts are most visible in the local labor markets in which the industries exposed to foreign competition are concentrated. Adjustment in local labor markets is remarkably slow, with wages and labor-force participation rates remaining depressed and unemployment rates remaining elevated for at least a full decade after the China trade shock commences. Exposed workers experience greater job churning and reduced lifetime income. At the national level, employment has fallen in the US industries more exposed to import competition… but offsetting employment gains in other industries have yet to materialize.”

“The China Shock” rebutted the notion that automation was the principal driver of U.S. manufacturing job losses and that China had little to do with stagnating U.S. manufacturing output. The study found that “import growth from China between 1999 and 2011 led to an employment reduction of 2.4 million.” (See Graph 4 on next page.) This represents almost half the manufacturing jobs lost in the U.S. during this period. And this estimate is conservative. Other studies find large, or larger, China-induced job losses.

The non-defense sector and a declining defense industrial base

The defense industrial base is the private and public capabilities that design, produce, and maintain the platforms and systems on which U.S. warfighters depend. It is a parallel supply chain dedicated to U.S. military needs, it also interacts with and depends on non-defense supply chains for a variety of skills and products.

Graph 4

U.S. MANUFACTURING EMPLOYEES (in MILLIONS)

SOURCE: FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST. LOUIS. ALL EMPLOYEES, MANUFACTURING, THOUSANDS OF PERSONS, ANNUAL, SEASONALLY ADJUSTED. SEP 16, 2020

In a 2018 DoD report Assessing and Strengthening the Manufacturing and Defense Industrial Base and Supply Chain Resiliency of the U.S., “the decline of U.S. manufacturing capabilities and capacity,” and the industrial policies of competitor nations, “notably the economic aggression of China,” were two of the five greatest risks weakening the DIB. Quoting from a National Security Strategy report, it said:

“The ability of the military to surge in response to an emergency depends on our Nation’s ability to produce needed parts and systems, healthy and secure supply chains, and a skilled U.S. workforce. The erosion of American manufacturing over the last two decades, however, has had a negative impact on these capabilities and threatens to undermine the ability of U.S. manufacturers to meet national security requirements.”

A vibrant manufacturing sector develops workforce and managerial skills and knowledge. Spillover of this development into other sectors can increase the productivity of other industries and make everyone better off. Consequently, the declining domestic manufacturing base degrades the country’s industrial process and manufacturing capabilities makes it difficult for defense manufactures to hire and retain workers with requisite skills from other sectors when needed.

Instead, defense procurement also increasingly relies on single suppliers and even suppliers from adversarial countries for critical defense items. The location of manufacturing research and development centers in other countries, especially China, also undermines future U.S. innovation since these jurisdictions and the foreign nationals that staff the centers are subject to different intellectual property laws that, according to the Department of Defense (DoD), “will impede U.S. access” to this research.

Chinese neo-mercantilism

While the tone of the DoD assessment is blunt and alarming, many other assessments from the private sector also concluded that Chinese actions undermine U.S. economic security. After 1945, the U.S. designed and supported an increasingly open global trading system that was primarily interested in reducing protectionism and other neo-mercantilist practices among like-minded countries. But China came into this system and rejected these rules. As a 2016 U.S. Trade Representative report (issued before Donald Trump came to office) described it, China “… seeks to limit market access for imported goods, foreign manufacturers and foreign service suppliers, while offering substantial government guidance, resources, and regulatory support to Chinese industries. The principal beneficiaries of these policies are state-owned enterprises, as well as other favored domestic companies attempting to move up the economic value chain.”

China selectively places all the resources of the state behind companies and industries that it deems strategically important. It then supports them in ways that ignore traditional market mechanisms, especially the need to earn a profit. For over two decades, China grossly undervalued its exchange rate in order to subsidize exports and tax imports. It also used domestic regulations and policies to favor its own companies through loan subsides, land grants and permitting preferences, and hobbled the growth of American firms in its domestic market by erecting discriminatory regulatory barriers.

One of the most potent Chinese strategies for technologically surpassing the U.S. is civilian-military “fusion.” This strategy seeks to facilitate the transfer of technological knowledge between the Chinese civilian and defense sectors in support of defense-related science and technology advancements. It effectively mobilizes all Chinese companies, state or private, in support of the State’s military and economic objectives.

In 2015, China took its state-capitalist model to a new level with the development of a comprehensive policy for economic, and eventually military, dominance. The “Made in China 2025” (MIC 2025) program detailed a comprehensive masterplan for economic and industrial modernization. Specifically, it seeks to create economic dominance in ten critical areas including: next-generation information technology; aerospace and aviation equipment; maritime vessels and engineering equipment; advanced rail equipment; energy-saving and new energy vehicles; and biopharmaceuticals and high-performance medical devices.

The plan subsidizes uncompetitive industries until they gain competitiveness, acquires foreign technology through intellectual property theft, extortion, and espionage, and places market and non-market barriers to entry on U.S. firms wishing to operate in China. China eventually realized how provocative MIC 2025 was and it stopped using the term. However, there is no indication that any of the policies changed.

Existing supply chain strategic vulnerability

As China sells more products to U.S. consumers and the U.S. military, the U.S. becomes increasingly vulnerable to espionage, economic and military sabotage, and large-scale data theft and its attendant misuse. Below are brief sketches of these vulnerabilities, as well as examples.

■ According to many corporate and U.S. government sources, China raised the art of espionage, or the process of obtaining military, political, commercial, or other secrets to a new level. While espionage in the military realm is to be expected, the degree to which China uses state assets, including the Peoples Liberation Army, in support of its corporations and engages in economic espionage against U.S. corporations and the public is shocking.

■ The “2020–2022 National Counterintelligence Strategy” highlighted China’s use of the global supply chain “to gain access to critical infrastructure, and steal sensitive information, research, technology, and industrial secrets.” It specifically noted that China, is “attempting to access our nation’s key supply chains at multiple points—from concept to design, manufacture, integration, deployment, and maintenance—by inserting malware into important information technology networks and communications systems.” One of the greatest threats from Chinese produced products concerns the installation of “trojan” chips or infiltration of viruses that alter product performance. This is especially relevant for power generation equipment and transportation products.

■ The connection between Chinese companies and illicit data acquisition is indisputable. Leaving aside the great lengths China goes to acquire economic and personal data through outright theft and espionage, there are many known examples of Chinese corporations surreptitiously collecting, or setting themselves up to collect, large amounts of customer data. TikTok, for example, defeated a privacy safeguard in Google’s Android operating system and collected unique identifiers from millions of mobile devices. Vodafone, one of the world’s largest telecommunication companies disclosed that it found a “backdoor” in equipment manufactured by Huawei Technologies. According to an analysis by software security firm Finite State, Huawei’s telecommunications equipment is more likely to contain exploitable flaws for malicious use than equipment from rival companies.

Below is a sampling of specific GSC related national security threats.

Bulk Power Supply Equipment: The U.S. acknowledged in 2014 that China possessed the capacity to shut down the U.S. power system. According to the more recent “2020–2022 National Counterintelligence Strategy,” this capacity is achieved not only through traditional spying, economic espionage, and cyber operations, but also through the manipulation of the supply chain. Specifically, it cites “increasing reliance on foreign-owned or controlled hardware, software, or services as well as the proliferation of networking technologies, including those associated with the Internet of Things…” Since 2009, approximately 85% of all newly purchased transformers by U.S. power operators were manufactured abroad, including more than 200 in China. Before 2009, none were imported from China. The threat is not just Chinese manufacturers, but also non-Chinese companies such Germany’s Siemens and Switzerland’s ABB Group that manufacture in China and then sell into the U.S.

Surveillance Cameras: The DoD purchased large numbers of Chinese surveillance cameras and the accompanying software and installed them on domestic and overseas military bases. This equipment endangers U.S. security by potentially providing China with a detailed window into U.S. military activities across the globe.

Small Drones: The problem with surveillance cameras is duplicated with small drones. Beside battlefield applications, in the civilian world small drones are popular for structural and physical monitoring of bridges, pipeline, and electric transmission lines, and for surveying wildfires and animal life. The Chinese company DJI is the world’s dominant producer of small drones with 74% of the market in 2019. DoD and other government purchases of Chinese drones were prohibited in 2019, but finding U.S. suppliers able to produce similar products is problematic.

Employees work on a mobile phone assembly line at a Huawei Technologies Co. production base in Dongguan, China, on March 6, 2019. (QILAI SHEN/BLOOMBERG/GETTY IMAGES)

China and the U.S. Automotive Industry

The U.S. automobile industry is by far the largest and most important manufacturing sector in the U.S., and it is critical for the economic health and prosperity of the country. There are close to one million people directly employed in vehicle and parts manufacturing. When other jobs such as auto dealership employees are included, the industry supports approximately 10 million workers, or 1 in 20 domestic jobs. This economic output equals roughly 6% of U.S. GDP.

Although U.S. consumer acceptance of electric vehicles (EV) is tepid, China and Europe have embraced this technology as an alternative to the internal combustion engine. China included EVs in its MIC 2025 program and sees EV development as a way to leapfrog over the U.S. and dominate mobility in the 2030s.

U.S. vehicle manufactures are acutely aware of the China threat. However, they are disadvantaged in responding because they face an extremely powerful state that both manipulates markets against them, and uses a large array of non-market, coercive, state-backed policies and strategies to undermine their response. As a result, American vehicle manufacturers potentially may go the way of shipbuilding or passenger railcar manufacturing. There will be no need to employ Americans in this industry, if China builds all the cars.

Although China exported just under 700,00 passenger vehicles in 2019, many auto companies are expanding manufacturing in China in anticipation of selling into the global market. China-produced vehicles would then represent a serious threat, not only to American jobs, but also to privacy and cyber security. The Chinese government could collect huge amounts of data on Americans or place backdoor devices in vehicles or components sold to Americans.

While the U.S. government is aware of the economic and industrial threat posed by China in areas like artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and 5G, it largely ignores the emerging and accelerating danger along the vehicle supply chain. If it continues to do so, it may concede what is one of the most, if not the most, important manufacturing sector of the U.S. economy.

This photo taken on April 11, 2019, shows employees working on the JAC (Anhui Jianghuai Automobile Group) Motor assembly line at JAC’s factory in Hefei in China’s eastern Anhui province. (KELLY WANG/AFP/GETTY IMAGES)

Railcars: Chinese Railway Rolling Stock Corp (CRRC) is the beneficiary of the full array of helpful China state policies. As a result, CRRC undercuts its competitor’s prices and sold approximately $2.7 billion of railcars to four American cities (Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles and Philadelphia). For several years, before being prohibited by Congress, the Washington, D.C. Metro also sought to purchase CRRC railcars. With the scores of thousands of U.S. defense and national security personnel using the Washington D.C. Metro to commute to work every day, the espionage, sabotage, and data theft risk were obvious. The U.S. no longer manufactures passenger railcars and now it is the U.S. doing the low profitability assembly work. It is telling how China advanced up both ends of the “Smile Curve” with this product and how the economic roles have been reversed.

Rare Earth Elements (REE): REE such as dysprosium and europium are used in many civilian products such as cell phones, computers, flat-screen televisions, and high-strength magnets used by alternative energy technologies, e.g., wind turbine generators and batteries of hybrid and electric vehicles. Military applications include components of jet engines, missile guidance systems, antimissile defense systems, satellites, and communication systems. According to the U.S. Geologic Survey, between 2011 and 2017, China produced approximately 84% of the world’s REEs and it also has a near-monopoly on the processing of these elements. Since the U.S. has no capacity to separate rare earths elements, produce metal, alloys or magnets it is effectively 100% import dependent on China for these products. In 2010 China curtailed shipments of REEs to Japan over a maritime dispute. Since that time, the U.S. military has been seriously concerned about its own access to REE. In response, the U.S. government has helped fund the development of the single major REE mine, Mountain Pass, in the U.S.

Drugs: Before generic drugs are processed into finished products, they start as active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, approximately 80% of API generic drug manufacturers are located outside of the U.S., and Chinese companies are a significant and growing share of these manufactures. For some of the drugs Americans consume, such as antibiotics and blood pressure medication, Chinese manufacturers have a virtual monopoly on API production. This high dependence is dangerous because if tensions with China were to rise and supplies interrupted, the withholding of APIs could seriously and negatively affect the health of millions of Americans. And even if China chose not to totally restrict API sales, they could create shortages or cause prices to escalate rapidly.

What the above examples all have in common is the inability or difficulty of avoiding Chinese-made products. There are no, or few alternative American or even allied country suppliers, and those that may exist often are inferior or more costly. The inability or extreme difficulty of avoiding Chinese-made products is a direct result of how MNCs and China have reconfigured the GSC.

Using GSCs to advance U.S. national security

While media attention focused largely on the GSC threat to the U.S., the GSC also provides the U.S. with opportunities to enhance its national security and weaken adversaries, particularly China. Indeed, the Trump administration increasingly attempts to use GSC related measures to advantage America. As Adam Segal of the Council on Foreign Relations described this new “high-tech Cold War,” the Trump Administration is “restricting the flow of technology to China, restructuring global supply chains, and investing in emerging technologies at home.” Below are specific examples:

Semiconductors: One of China’s greatest supply chain vulnerabilities concerns advanced semiconductor chips. Semiconductors are electric components that go into products such as memory chips, microprocessor, and integrated circuits. They are essential to almost all electronic products from consumer phones and computers, to missile and jet fighter. In 2019, imported chips represented over 80% of the computer chips China used, and the import bill, in excess of $300 billion, substantially exceeded that for crude oil. China is extremely dependent on American sourced semiconductors, whether purchased outright from U.S. suppliers, or manufactured under license. Continued and increasing disruption of the semiconductor flow would severely undermine China’s ability to advance many of its most important technology programs such as Huawei’s 5G network. After a series of increasingly prohibitive measures, the Trump administration in August 2020 finally restricted the sale of U.S. produced or designed semiconductors to Chinese entities.

Satellites: Surprisingly, U.S. corporations such as Boeing, Maxar Technologies and the investment firm Carlyle Group all have assisted China in deploying advanced U.S. satellite communications in support of their military and security services. While the Chinese government and its companies are barred from directly purchasing U.S.-made satellites, they have skillfully found ways to use offshore companies to purchased advanced U.S. satellites and then lease back bandwidth to their military and security organizations. The U.S. government is still wrestling with how to close the legal loopholes that make this possible.

Basic Scientific Research: A large area of vulnerability for the Chinese GSC concerns access to advanced research in the U.S. Basic research is the foundation upon which most all advanced manufacturing rests, and as noted, China is extremely aggressive in acquiring the best American scientific ideas to support its industrialization. Among other methods, China developed programs to attract top U.S. scientific talent by targeting U.S. college and university researchers and paying them generously. In many cases, it even brought the researchers to China to establish parallel labs to those operating in the U.S. Much of this cutting-edge research includes some with direct military applications, and it was conducted with the cooperation of many U.S. universities. After the extent of this threat became clear, the Federal Bureau of Investigation investigated and indicted several prominent scientists. A number of institutions also paid multimillion-dollar fines to settle charges. While final rules for China’s relationship with U.S. research institutions are being designed, the most threatening practices have stopped. But given the potential benefits from this activity, China is unlikely to reduce its efforts in this area.

In response to GSC vulnerability and China’s abuse of the international trading system, three policy options emerge. These are: renewed engagement, decouplement, and industrial policy adoption. While the difference between engagement and the other two perspectives is stark, i.e., cooperation or competition, there often is overlap between decouplement and industrial policy. The difference between the two tends to be where one places the central emphasis, i.e., limiting the U.S.-China relationship, or rebuilding America’s industrial capacity.

Renewed engagement

The ranks of those advocating for renewed engagement with China have thinned considerably since 2016. Supporters of this position tend to come from an older generation of businessmen, diplomats, policy advocates, and academics. At its top, the group is largely populated by people who had very successful careers building the U.S.-China relationship, or who have become wealthy off it. These advocates want to avoid conflict, minimize competition, and build cooperation with China. Engagement and globalization are still seen as a win-win for both sides.

Engagers think too antagonistic a response to China would be counterproductive, especially if it is really trying to push China into an economic or political crisis. In a prominent Washington Post op-ed from July 2019, more than 100 engagers, including Stapleton Roy, Susan Thornton, and Ezra Vogel argued that an alternative policy risks losing decades of hard-built relationships, unnecessarily elevates the risk of military confrontation, and may even lead to a new era of McCarthyism in America. On the GSC they wrote:

“U.S. efforts to treat China as an enemy and decouple it from the global economy will damage the U.S.’ international role and reputation and undermine the economic interests of all nations. U.S. opposition will not prevent the continued expansion of the Chinese economy, a greater global market share for Chinese companies and an increase in China’s role in world affairs….If the U.S. presses its allies to treat China as an economic and political enemy, it will weaken its relations with those allies and could end up isolating itself rather than Beijing.”

Noticeably absent from this group are many U.S. manufacturing businesses that pioneered the GSC relocation to China, and that previously were ardent supporters of engagement. The cause of this change is found in the declining profitability of many U.S. operations in China. The unmooring of the U.S.-China relationship from its business foundation seriously weakened U.S. support for an accommodative policy. In particular, there is less of a counterbalance to deflect or defeat longstanding China critics among the labor and defense communities.

The last major bastion for pro-engagement policies among the U.S. business community is financial service companies, especially the large banks, asset managers, and private equity firms. Since these firms had less in-country exposure to China, they have not had the same punishing experience as U.S. manufacturers. Also, chimera or otherwise, many of these companies think they still can become fabulously wealthy by engaging with China. Undoubtedly and regardless of its national security implications, some of them will be correct.

Decouplement

Derek Scissors, a policy scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, is a prominent advocate of decoupling from China. Scissors sees decoupling as a third way between doing nothing to counter China’s harmful economic actions, and punitive polices built around sanctions and other aggressive measures. Scissors wants to restrict and shrink “the economic relationship for an indefinite period because parts of it are harmful” to the U.S. The purpose of decoupling is not to destroy bad Chinese actors, but to stop enriching them.

Scissors proposes an array of measures including better use of countervailing and antidumping duties, stricter and more efficient use of export controls, continued restrictions on Chinese inbound investment, and new, stricter restrictions on U.S. investment, including portfolio investment in China. Decoupling supports relocating strategic supply chains, like PPE, into the U.S. or friendly countries. In many cases, it will be necessary to outlaw the use or consumption of Chinese products or materials. Particularly during the beginning of decoupling, Scissors says only a small number of supply chains should be relocated. This will avoid unjustified protectionism and allow the U.S. government and industry to learn how best to undertake these transfers. Coordination and sharing relocated supply chains with like-minded countries also is important.

Large scale U.S.-China decoupling will impose economic costs on both China and the U.S. However, the precise impact on U.S. inflation, innovation, and the standard of living is hard to know. Some critics of decoupling argue that it can cost trillions of dollars and that it is therefore not possible. However, this is a strawman argument since no serious advocate is arguing for a total decoupling.

According to Scissors, even a limited decoupling would need tens of billions of dollars of U.S. government support and it would have to contend with Chinese retaliation. The gains, however, will be “impressive” since it will reduce “Chinese distortions of the American and global economies.” While decoupling will not create millions of new American jobs, it can save what high-quality jobs and companies America has left. Decoupling is about “avoiding losses rather than generating benefits.”

Technicians monitor a machine that manufactures 300mm silicon wafers at the Applied Materials Inc. Maydan Technology Center in Santa Clara, California, U.S., on Sept. 1, 2011. Applied Materials Inc. develops, manufactures, markets, and services semiconductor wafer fabrication equipment and related spare parts for the worldwide semiconductor industry. (DAVID PAUL MORRIS/BLOOMBERG/GETTY IMAGES)

Industrial policy

To Arthur Herman, a policy scholar at the Hudson Institute, industrial policy (IP) refers to “a program of economic reforms that give the government extraordinary authority, as well as fiscal and regulatory powers, to change a country’s industrial structure or—less ambitiously—promote a targeted sector of the economy.” IP advocates are alarmed by the relative deindustrialization of America and by a fear that the U.S. lead in technology is disappearing.

Industrial policy has a long and negative history in the U.S. primarily because it goes against so many market precepts, mythological or otherwise, that dominate American thinking. As the American economist Gary Hufbauer remarked, before “…the Trump era, industrial policy—in the sense of detailed government guidance of economic life—was regarded as a hangover from the Soviet Union, to be embraced only by misguided developing countries.” Critics of industrial policy say that it “does not work” since the government is “incapable of picking winner and losers.” They also argue, with some justification, that IPs are prone to abuse by politicians and industry.

IP advocates assert that the critics present a distorted picture of IP, and that the recent American experience with markets has been a great deal less impressive than many economists and policy advocates claim. In particular they bristle at central planning comparisons and note that IP, like mercantilism, is a form of capitalism. As Herman said: “…limiting government’s role to merely umpiring market mechanisms is hurting both our economic future and our national security. [Policy options] beyond market fundamentalism…exist [and] a failure to pursue these alternatives might put us on a different road to serfdom.” The point is not “…to curb private enterprise but to spur it in a new direction…”

IP currently is enjoying a revival both on the left and right, and a large number of politicians such as Senators Marco Rubio, Sherrod Brown, and Sheldon Whitehouse, and former Ambassador to the United Nation Nikki Haley are supportive of a greater government role in the economy. A national-security-oriented IP would use a coherent and narrow set of government measures to reduce specific national security vulnerabilities such as in artificial intelligence, quantum computing, semiconductors, and 5G. One of the most high-profile current IP efforts is found in legislation to increase the domestic U.S. manufacturing of semiconductors and block as much indigenous Chinese chip development as possible. A broader IP would attempt to reinvigorate an entire industry, such as the automotive sector, by renewing or creating the full supply chain in the U.S. and friendly countries.

The industrial policy debate raises a deeper U.S. conflict on American values and capitalism, and the proper relationship between the private sector and the state. Heretofore, questioning the utility of markets, free trade, and globalization has not been a winning formula in the U.S. The issue now is: Has the competition with China altered this reflexive ideological attachment? Or perhaps, has American generational change made IP more acceptable?

discussion questions

1. Is China an economic partner or strategic economic threat? Can China be brought back into an American-led international economic system?

2. Is decoupling from China in the American interest? How much reshoring is practical or advisable?

3. Should the U.S. redefine the appropriate role of government in the U.S. economy in order to help corporations compete better with China? Can the U.S. compete successfully without a more cooperative relationship between the public and private sectors?

4. Would government intervention through an industrial policy invariably result in lower economic growth and lower prosperity? Even if it did, might such a policy be justified given other security and social goals?

5. What are the dangers of an ever-intensifying technology and economic Cold War with China?

suggested readings

Atkinson, Robert. How Nine Flawed Policy Concepts Hinder the United States From Adopting the Advanced-Industry Strategy It Needs. ITIF. 2020. Few policymakers and even fewer pundits or economic analysts understand U.S. competitiveness problems in a way that would lead them to the logical conclusion that China is a major economic threat and that a national innovation and competitiveness strategy is the required solution.

Gertz, Geoffrey and Miles M. Evers. Geoeconomic Competition: Will State Capitalism Win? Washington Quarterly. Summer, 2020. The authors examine the unfair fight between the U.S. and China in the corporate sphere. They detail three broad ways for the U.S. government to leverage the private sector in an effort to reduce China’s economic advantage.

Herman, Arthur. America Needs an Industrial Policy. American Affairs. Hudson Institute. 2019. There has been a recent shift in mood and attitude about the proper role of government in shaping America’s economic destiny. Fear that limiting government’s role to merely umpiring market mechanisms is hurting both our economic future and our national security. Policy options beyond market fundamentalism exist, and a failure to pursue these alternatives might put us on a different road to serfdom.

Mann, Katherine. For Better or Worse Has Globalization Peaked? Citigroup. 2019. Personal experience has led many to conclude that globalization is a failure, Mann, however, thinks that a retreat from globalization will so reduce output that everyone will be worse off. The challenge, therefore, is “to revive trade integration and find strategies to better distribute those gains. The key to this is in better domestic economic policies.

Rubio, Marco. American Industrial Policy and the Rise of China. American Mind. 2019. Senator Rubio makes the case for reinvigorating American manufacturing and strengthening national security through targeted, domestic economic interventions.

Scissors, Derek. Partial decoupling from China: A brief guide. AEI. 2020. Chinese state-capitalism has seriously damaged America’s economic intersts. If it is not checked, it will continue to destroy American jobs and industries. A partial and strategic decoupling is the only way to protect American economic and security intersts.

Don’t forget: Ballots start on page 104!!!!

To access web links to these readings, as well as links to global discussion questions, shorter readings and suggested web sites,

GO TO www.fpa.org/great_decisions

and click on the topic under Resources, on the right-hand side of the page.