Chapter 6

Standing Firm: Andrew Jackson

IN THIS CHAPTER

Entering politics

Entering politics

Losing the presidential election in 1824

Losing the presidential election in 1824

Winning the presidency

Winning the presidency

Paving the Trail of Tears

Paving the Trail of Tears

Retiring gracefully

Retiring gracefully

Compared to his predecessors, Andrew Jackson was an unlikely candidate to win the presidency. He grew up in poverty, was almost illiterate, had no political connections, and refused to identify with the ruling elite.

Jackson remains one of America’s most controversial presidents. Some consider him a hero, a champion of the people, and the first strong president in U.S. history. Others see him as a gambler, wife stealer, “Indian killer,” and the founding father of political corruption in the United States. The truth is that he was all of these things.

Jackson’s Early Career

Jackson retired from the Senate in 1798 and became a justice on the Tennessee Superior Court for the next six years. He gave up his judicial position to enjoy his marriage and dedicate himself to becoming a successful plantation owner. Within a few years, Jackson had over 100 slaves working on his Tennessee plantation, The Hermitage. To supplement his income, he got involved in horseracing and acquired a reputation as a top-notch horse breeder. Jackson seemed to have it all.

Going to war

In 1812, the United States and Britain went to war. Britain aligned itself with several Native American tribes that were also hostile to the United States. One of these tribes, the Creek, massacred 250 settlers in the Mississippi territory. Jackson organized a militia and went after the Native Americans. He found them in 1814. As a gesture of goodwill, he let all the women and children go free. Then he attacked the men, killing more than 800 Creek warriors. Later, he forced the Creek to sign a treaty with the U.S. government, ceding over half of present-day Alabama to the United States.

Impressed, President Madison appointed Jackson major-general in 1814 and sent him south to defend New Orleans. Jackson organized one of the most unique militias in U.S. history. He recruited frontiersmen, pirates, slaves, Frenchmen, and whomever else he could find. When the British launched a frontal assault on January 8, 1815, Jackson was ready. In the battle of New Orleans, Jackson’s militia killed over 2,000 British soldiers, while losing only 8 men. Jackson was a national hero. (He found out later that he didn’t need to fight that battle — by the time it had taken place, the war was over.)

Saved by a political enemy

President Madison named Jackson commander of the army of the southern district where the Seminole tribe, residing in Spanish-controlled Florida, made constant raids into U.S. territory. In 1817, President Monroe instructed Jackson to do whatever was necessary to stop the raids. Jackson pursued the Seminoles into Florida and wiped them out. He also executed two British citizens accused of inciting the Seminoles to make raids against U.S. settlers.

Both Spain and Britain complained bitterly about Jackson’s behavior. Even some members of Monroe’s cabinet wanted to send Jackson to jail. However, one — just one — member of the cabinet defended Jackson. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, negotiating with Spain for the sale of Florida to the United States, blamed the Spanish for the debacle, arguing that it was Spain’s responsibility to keep the Seminoles in order. He suggested that Spain make amendment by selling Florida to the United States. Adams prevailed, Jackson’s reputation rose, and the United States bought Florida from Spain.

Suffering through the Stolen Election of 1824

After acquiring Florida from Spain, President Monroe appointed Jackson governor of Florida. Jackson wasn’t happy in the job — he left office after serving for just four months. He returned home to Tennessee and was appointed to the U.S. Senate for the second time in 1823. A group of Jackson’s supporters were planning to have him run for president, and a national-level office was the first step.

In the 1824 election, Jackson came in first, winning the popular vote and 99 Electoral College votes. But it wasn’t enough. With no candidate winning a majority (131) of the Electoral College votes, the election went to the House of Representatives, where each state had one vote. The Speaker of the House, Henry Clay, who came in fourth in the presidential race, threw his support behind John Quincy Adams, who had come in second. With Clay’s support, Adams won the presidency.

- Liberalizing electoral laws

- Opposing tariffs (because the average person wanted to buy cheap foreign goods)

- Favoring states’ rights over the federal government

President Andrew Jackson (1829–1837)

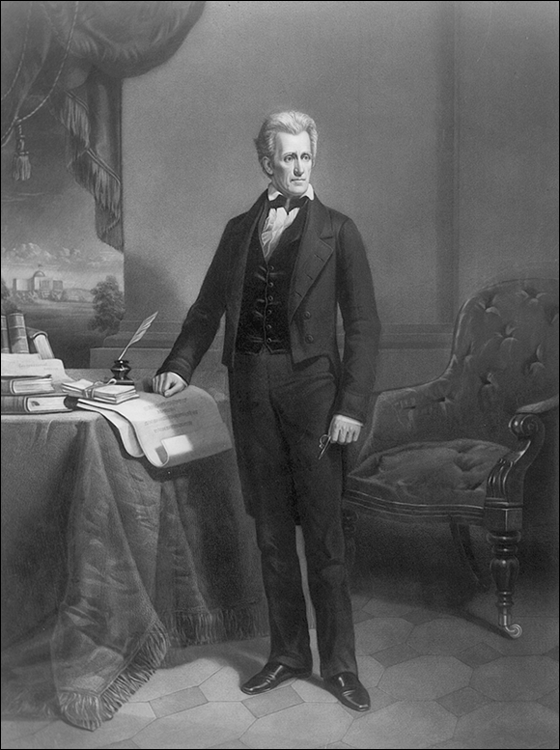

After the bitter experience of losing the presidency in 1824, Jackson, shown in Figure 6-1, challenged the incumbent President Adams — this time with a new political party behind him. He ran as a candidate of the people, painting Adams as a candidate of the wealthy. He especially focused on the Tariff of Abominations, which hurt the average citizen by increasing duties on imports. Adams never had a chance. When the vote was in, Jackson received 178 electoral votes to Adams’s 83.

Andrew Jackson was truly a president of the people. He believed that government needed to look after the people who needed the most help — poor, hard-working U.S. citizens. He wanted to be a president for the poor rather than the rich. At the same time, if you were a friend or a supporter of Jackson, you could expect handsome rewards.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 6-1: Andrew Jackson, 7th president of the United States.

Dealing with states’ rights and tariffs

Andrew Jackson’s first great political challenge occurred in the early 1830s. He urged Congress to eliminate the Tariff of Abominations, which levied high duties on foreign goods. In 1832, Congress lowered the tariff but didn’t abolish it, giving Southern states reason to complain.

South Carolina pushed specifically for nullification of the tariff and passed an ordinance of nullification in 1833, declaring the federal tariff void in that state. In addition, South Carolina proclaimed that if the federal government wouldn’t allow it to nullify the tariffs, it would secede.

Although Jackson supported states’ rights, he saw this as an act of treason. He told the state’s leaders that he would do whatever was necessary to preserve the Union — including using force. Ironically, his old enemy Henry Clay came to the rescue. Clay proposed a new tariff that was acceptable to everyone, including the Southern states. South Carolina repealed its ordinance of nullification, and a civil war was narrowly avoided.

Hating banks

Throughout his life, Jackson hated banks. He considered them unnecessary and felt that they only cheated average citizens. In particular, he despised the National Bank of the United States. If it was necessary to have banks, Jackson believed that states, not the federal government, should control them.

In 1834, the Senate censured Jackson for his actions, but because the House voted to support him, the Senate’s censure didn’t faze him at all. The National Bank reacted by calling in loans it had given to state banks. The attempt to punish Jackson by limiting the supply of money in the United States forced the country into a recession. Jackson blamed the National Bank and its supporters, and the public backed him. With Jackson opposed to the National Bank, Congress did not renew the bank’s charter, and it went under in 1836.

Jackson’s hatred for the National Bank resulted in economic chaos. He put most of the federal money into state banks, and they in turn loaned out the money. These smaller banks didn’t have gold and silver reserves to back up their loans. Inflation set in, and paper money became worthless. In 1836, Jackson proclaimed that public lands could only be paid for with gold and silver. This resulted in the panic of 1837, which I discuss in the next chapter.

Forcing Native Americans west

The most controversial policies of the Jackson administration were ones directed toward Native Americans. Jackson developed an intense dislike for Native American tribes after he experienced the brutality of several tribes early in his military career. As president, he supported the forced resettlement of many tribes.

When the state of Georgia insisted that the Cherokee nation abide by the laws of Georgia, as well as hand over its lands to the state, Jackson didn’t interfere. He believed that the United States needed to expand. He also believed that if Native Americans stood in the way of the expansion, they needed to be removed. He officially claimed that the federal government had no jurisdiction over state matters in this case and refused to aid the Cherokee.

The Cherokee appealed to the Supreme Court. In the case of Worcester vs. Georgia in 1832, Chief Justice Marshall ruled that only the federal government, not the states, had jurisdiction over Native American tribes. So the Cherokee were bound only by federal law — not state law.

In 1830, Congress and President Jackson passed the Indian Removal Act, and the U.S. government established the Bureau of Indian Affairs to handle all Native American issues. The Removal Act demanded the removal of many Native American tribes east of the Mississippi. When tribes refused to leave their homelands, Jackson and the military responded brutally. This brutality resulted in the Black Hawk War of 1832, when the Sac and Fox nations refused to voluntarily leave their homelands in present-day Wisconsin.

In 1834, Congress and President Jackson decided to create a land for Native Americans to inhabit. They established the Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma. Not surprisingly, most tribes weren’t eager to leave their homelands. The conflict resulted in a forced resettlement of Native Americans and in the famous Trail of Tears. Not many U.S. citizens opposed Jackson’s policies toward Native Americans. The country was ready to move westward. Some notable critics included Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams. Clay even thought Jackson’s policies represented a stain on U.S. history.

Getting tough with France

The Jackson era didn’t bring much to the realm of foreign policy, with one major exception. In 1831, France, acting in accordance with international law, agreed to pay for the damages it caused to U.S. ships during the Napoleonic Wars. (The French plundered American ships during the Napoleonic Wars.) France didn’t make good on this promise until 1834, when Jackson cut off diplomatic relations with France and threatened to seize all French property in the United States. France finally caved in and paid the damages.

Cruising toward reelection

The election itself was no cliffhanger. Andrew Jackson was the nominee for the Democratic Party. Henry Clay got the nod from the opposing party, the National Republicans (which would become the Whigs by 1834). Jackson slaughtered Clay in the voting booth. Jackson ended up winning 219 Electoral College votes to Clay’s 49.

Deciding what to do with Texas

The question of what to do with Texas rattled several presidents. John Quincy Adams tried to buy it from Mexico, but the Mexicans refused his $1 million offer. Andrew Jackson upped the ante to $5 million, but Mexico still wouldn’t bite. Texas turned into a major headache for Jackson.

When Mexico won independence from Spain in 1821, the new Mexican government allowed U.S. settlers into Texas. In the early 1830s, the U.S. settlers, headed by the Austin family, outnumbered the native Mexicans by almost 4 to 1. Mexico started to impose new laws on the settlers, and they began to rebel. Mexico’s insistence that slavery be abolished and that U.S. settlers convert to Catholicism proved to be the major cause for rebellion. By 1832, many of the U.S. settlers demanded a repealing of the laws. After Mexico refused, a rebellion broke out in 1835.

In 1836, the U.S. settlers, or Texians, declared their independence from Mexico. The Mexican president, General Santa Anna, was not amused — he fought to keep his country intact. A small group of Texians, helped by U.S. citizens, set up a fort in an old Spanish mission in San Antonio called the Alamo. Shortly thereafter, the Mexican army (5,000 men strong) attacked and killed all 187 defenders. This action incensed many U.S. citizens and the remaining Texians in Texas. Six weeks later, a larger force, led by Sam Houston, defeated the Mexicans, and Texas won its independence.

After declaring independence, the new country of Texas ratified the U.S. Constitution and wanted to join the United States. Jackson faced some problems. First, Mexico made it clear that it objected to Texas joining the United States. Jackson didn’t want to go to war over the matter. Second, many Northern Whigs and Democrats opposed the admission of Texas as a slave state. So Jackson did what every good politician does — he delayed the decision until his last days in office. Before he stepped down, Jackson recognized the Republic of Texas as an independent country. This move proved to be the first step toward the annexation of Texas.

Reaching retirement

By 1836, Jackson was ill with tuberculosis and wanted to abide by Washington’s two-term limit. Unlike Monroe, Jackson sought to make sure that his ideas and policies survived his retirement, so he handpicked his successor. His choice was Vice President Martin Van Buren, one of his most loyal allies and advisors. Van Buren won easily in 1836.

Jackson returned home to his plantation. Like his predecessors, he ran into financial troubles and borrowed heavily in his last years. In 1844, Jackson came out of retirement for the upcoming election. Disappointed with Van Buren, who lost in 1840, and now opposed to annexing Texas, Jackson turned away from his old friend and backed James Polk, another good friend, for the presidency in 1844. Jackson’s selection was good enough for the Democrats. Polk received the nomination and won the presidency in 1844. A few months later, in June 1845, Andrew Jackson passed away in his sleep.

In 1796, the federal government formed a new state out of the western part of North Carolina, calling it Tennessee. Andrew Jackson successfully ran for the House of Representatives and became a U.S. senator one year later. In Congress, he supported the Democratic-Republicans, headed by Jefferson and Madison, and criticized President Washington for being too lenient with Native Americans.

In 1796, the federal government formed a new state out of the western part of North Carolina, calling it Tennessee. Andrew Jackson successfully ran for the House of Representatives and became a U.S. senator one year later. In Congress, he supported the Democratic-Republicans, headed by Jefferson and Madison, and criticized President Washington for being too lenient with Native Americans. Even though John Quincy Adams saved Jackson’s job in 1818, the two became bitter enemies. Adams beat Jackson in a bitterly contested election for the presidency in 1824, and Jackson beat Adams four years later. Jackson blamed Adams and his supporters for the death of his wife, while Adams considered Jackson unfit for the presidency. To quote Adams, Jackson was “… a barbarian who could not write a sentence of grammar and hardly could spell his name.”

Even though John Quincy Adams saved Jackson’s job in 1818, the two became bitter enemies. Adams beat Jackson in a bitterly contested election for the presidency in 1824, and Jackson beat Adams four years later. Jackson blamed Adams and his supporters for the death of his wife, while Adams considered Jackson unfit for the presidency. To quote Adams, Jackson was “… a barbarian who could not write a sentence of grammar and hardly could spell his name.” By the time Jackson ran for the presidency in 1824, the electoral process had changed. Previously, state legislatures decided who won the state, and many states had given this power to the people. Further, the property requirements necessary to vote had disappeared, giving every white male the vote in most states. Jackson won the states where the people selected the president but lost most of the states where the state legislatures picked the president.

By the time Jackson ran for the presidency in 1824, the electoral process had changed. Previously, state legislatures decided who won the state, and many states had given this power to the people. Further, the property requirements necessary to vote had disappeared, giving every white male the vote in most states. Jackson won the states where the people selected the president but lost most of the states where the state legislatures picked the president. Andrew Jackson took the rewarding of political friends to new heights. He believed in the spoils system, which refers to the system of rewarding political friends and supporters with public jobs. (See the sidebar “

Andrew Jackson took the rewarding of political friends to new heights. He believed in the spoils system, which refers to the system of rewarding political friends and supporters with public jobs. (See the sidebar “ Jackson’s inauguration almost resulted in the destruction of the White House. He opened the White House for a reception for the “common man,” who, after consuming too much alcohol, roamed through the presidential mansion destroying everything in sight. Jackson snuck out of a window to avoid the chaos and spent inauguration night in a hotel.

Jackson’s inauguration almost resulted in the destruction of the White House. He opened the White House for a reception for the “common man,” who, after consuming too much alcohol, roamed through the presidential mansion destroying everything in sight. Jackson snuck out of a window to avoid the chaos and spent inauguration night in a hotel.