Chapter 11

Reconstructing the Country: Johnson, Grant, and Hayes

IN THIS CHAPTER

Facing the first impeachment proceedings: Johnson

Facing the first impeachment proceedings: Johnson

Gaining fame for military exploits and corruption: Grant

Gaining fame for military exploits and corruption: Grant

Stealing an election and fighting corruption: Hayes

Stealing an election and fighting corruption: Hayes

The first president I cover in this chapter — Andrew Johnson — was a stubborn, uncompromising president, who constantly fought with Congress. This led to his impeachment by the House of Representatives, giving him the distinction of becoming the first U.S. president to be impeached.

Next, I consider a true American hero, General Ulysses Grant. He was a great military leader, but he was a mediocre president whose administration was dominated by corruption and scandals.

Finally, Rutherford Hayes was an honest man who became president when the Republicans stole the election from the Democrats in 1876. This put a dark shadow on his presidency from the beginning. Despite this, he turned out to be a fairly capable president.

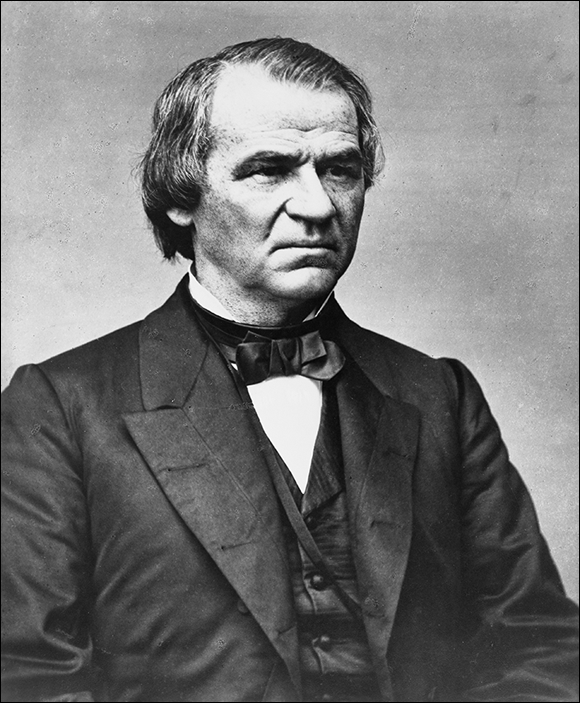

From Poverty to the Presidency: Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson, shown in Figure 11-1, holds the dubious distinction of being the first president impeached by the House of Representatives. He is also considered one of the least successful presidents in the history of the United States. While escaping impeachment by one vote in the Senate, Johnson, an ardent advocate of states’ rights and a blatant racist, managed to single-handedly prolong the plight of ex-slaves in the American South.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 11-1: Andrew Johnson, 17th president of the United States.

Getting into politics: Johnson’s early career

Johnson entered politics in 1829. Running on a working-class platform, championing poor whites, he won the office of alderman in Greenville, Tennessee, in 1829 and became the city’s mayor five years later. By this point, Johnson was a committed Democrat and a great admirer of Andrew Jackson. Only one year after his successful mayoral race, Johnson was elected to the Tennessee state legislature in 1835.

In 1843, he became one of the Democratic congressmen from Tennessee, a position he would hold until 1853, when he was elected to the governorship of Tennessee. Finally, in 1857, the state legislature elected him to be one of the senators for the state. Johnson proudly proclaimed, “I have reached the summit of my ambition.”

Johnson’s courageous act turned him into a symbol for Southerners loyal to the Union. President Lincoln rewarded him by appointing him the military governor of Tennessee.

Acting on his prejudices

Johnson used his position to act upon his deep-seated hatred for white plantation owners, who dominated Tennessee politics. He replaced public officials, arrested opponents, shut down newspapers that were critical of him, and confiscated the bank of Tennessee.

In 1864, Lincoln and the Republican Party rewarded Johnson’s loyalty to the Union by picking him to be Lincoln’s vice-presidential candidate. Johnson appealed to Democrats in the North, and Lincoln and the Republicans believed that Johnson could establish the Republican Party in the South after the Civil War. Suddenly, Johnson, a lifelong Democrat who despised the Republican Party, found himself on the Republican ticket.

President Andrew Johnson (1865–1869)

President Lincoln was assassinated six weeks after his second inauguration. Johnson found himself president of the United States on April 15, 1865; only six days after the Civil War had ended.

Reintegrating the South

The question of reintegrating the Confederate states into the Union, or Reconstruction, was left up to the former senator from Tennessee, a slave-owning Union advocate who hated plantation owners.

The Republican Party, which controlled Congress, pushed for punishment of the Confederate states and immediate voting rights for blacks. The Republicans mistakenly believed that the new president shared their beliefs.

Johnson, however, had different ideas. Johnson believed that only plantation owners and major Confederate leaders were to blame for the Civil War. He was interested in empowering the poor whites and punishing the Southern elite he so despised. He didn’t concern himself with the large slave population.

In May 1865, Johnson started implementing his version of Reconstruction:

He offered an unconditional pardon and amnesty, and restored all property rights to any Confederate who would swear loyalty to the Union.

Excluded from the proclamation, however, were large plantation owners. They had to seek an individual presidential pardon. This requirement allowed Johnson to humiliate them. The Southern upper class now had to beg the former tailor for presidential pardons. (Most of them asked for and subsequently received the presidential pardon from Johnson.)

- He forced the Confederate states to abolish slavery by ratifying the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

- He repealed the Confederate states’ ordinance of secession.

He renounced all Confederate debts.

The move let the former Confederate states regulate their own business. To the great disappointment of Johnson, they did this by electing major Confederate leaders to high-level state offices.

Ending a president’s Reconstruction

In the summer of 1865, Johnson, undeterred by the Black Codes, started returning to their original owners plantations that had been confiscated during the war and distributed to former slaves. Johnson decided that only the former slaveholders could properly control the black population in the South. In December 1865, Johnson proudly proclaimed that Reconstruction was now over and that Congress needed to readmit representatives from the Southern states.

Warring with Congress

The members of Congress were far from agreeing with Johnson’s declaration that Reconstruction was over. A civil war broke out between the two branches of government.

The radical wing of the Republican Party considered Johnson a Southern sympathizer. Reports of Southern states returning Confederate leaders to public office, as well as of widespread abuse of former slaves, further undermined Johnson and pushed Congress into trying to change some of Johnson’s policies.

Congress went on the offensive. In April 1866, Congress took the Civil Rights Bill and made it a part of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which guaranteed “equal protection of the laws” for every U.S. citizen.

Johnson openly opposed the amendment. He stumped for Democratic candidates, who shared his views, in the 1866 Congressional elections. His campaign swing turned into a disaster when he responded to continuous heckling from Radical Republicans by entering into fierce exchanges. The last straw came when Johnson compared himself to Jesus Christ and openly suggested that Lincoln was removed by divine intervention so that Johnson could become president. The media had a field day with the president. Johnson’s support for candidates from his old party backfired, and the Republican Party gained enough seats in the House to easily override any of Johnson’s vetoes.

Being impeached

Wanting to get rid of Johnson, the Republican leadership passed the Tenure of Office Act in 1867. The act prohibited the president from dismissing any federal officials without the consent of the Senate. Congress easily overrode Johnson’s veto of the act. In retaliation, an angry Johnson openly encouraged Southerners to oppose the new Reconstruction plan from Congress.

Johnson then rashly suspended his secretary of war, Edwin Stanton, who was close to the Radical Republicans. When Johnson attempted to dismiss him altogether, Stanton barricaded himself in his office with several armed guards. When the Senate refused to remove Stanton under the Tenure of Office Act, Johnson declared the act unconstitutional and removed Stanton anyway. (Johnson’s contention that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1926 — too late to help him.)

The Radical Republicans used the issue to start impeachment proceedings against the president. Johnson responded as only Johnson could — with a curse: “Let them impeach and be damned.”

In the House, impeachment was a foregone conclusion. Johnson was impeached on 11 counts, with the central issue being the violation of the Tenure of Office Act. In the Senate, a conviction was less certain. Many senators believed that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional in the first place, and they were less than enamored with the idea of having the Senate president pro tem, Benjamin Wade, a Radical Republican, become president. When the vote was tallied, 7 Republicans had crossed party lines and joined all 12 Democrats in the Senate by voting against convicting and removing the president. t. (The final tally was 35 for conviction, 19 against.) Johnson had survived being removed by one vote.

Serving out his term

Disgraced and disheartened, Johnson served out his term quietly, deadlocked with the Republican Congress. Even his foreign policy accomplishments were downplayed. When Johnson encouraged his secretary of state, William H. Seward, to purchase Alaska from Russia for $7,200,000, he was ridiculed. The purchase was widely referred to as “Seward’s Folly.”

In the summer of 1868, Johnson’s hopes of becoming the presidential nominee for the Democratic Party were dashed. He returned home to Tennessee, where he received a hero’s welcome. He returned to Washington, D.C., as a senator in 1875. He served just a few months of his term, though. He died of a stroke on July 31, 1875.

Enter a War Hero: Ulysses Simpson Grant

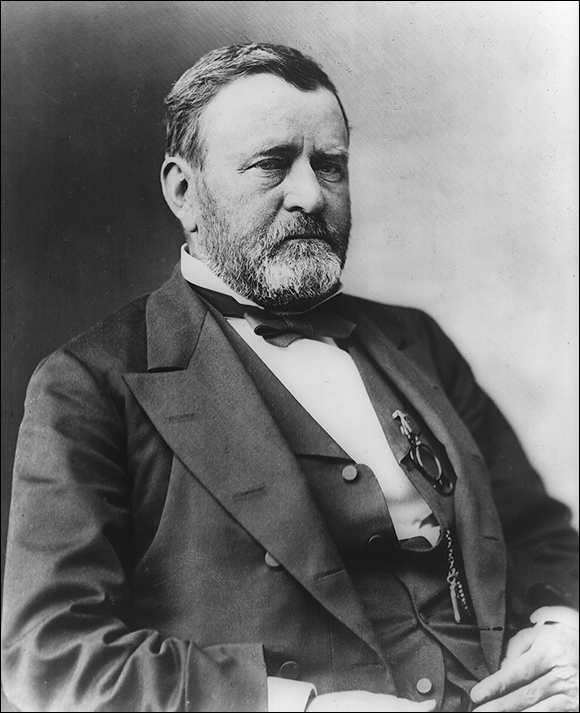

Grant’s two terms as president are usually considered to be the most corrupt of any of the presidencies in U.S. history. Why did an honest man suffer such horrible terms in office? For one reason, Grant, shown in Figure 11-2, ran the presidency like a military unit and appointed his friends to high-level positions. Most of these friends turned out to be corrupt. But Grant defended and helped them, undermining his credibility and reputation.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 11-2: Ulysses S. Grant, 18th president of the United States.

Grant’s early career

Grant failed at many ventures early in his career. He tried his hand at farming and the selling of real estate before settling on a job as a clerk in a leather store, where he worked with his brother.

The Civil War made Grant’s career. After the creation of the Confederacy and the attack on Fort Sumter (see Chapter 10), Lincoln called for local militia troops. Grant volunteered and became an officer in an Illinois regiment. He whipped the regiment into shape. Grant’s commanding officer was impressed, so he made him a colonel and sent him into battle.

Grant’s unit fought well in Missouri, and he was promoted to brigadier general in August 1861. Grant captured Forts Donelson and Henry in Tennessee, giving Lincoln the first major victories of the Civil War. In the process, he captured 14,000 Confederate soldiers and received the nickname “Unconditional Surrender” for always demanding unconditional surrender.

Becoming a war hero

The battle of Shiloh almost cost Grant his military career. He didn’t fortify his positions, waiting for reinforcements instead. When Confederate forces attacked, he was unprepared. Grant took the blame for the thousands of lives lost, and congressmen and cabinet officers urged Lincoln to fire Grant.

Lincoln stood by his man, saying, “I can’t spare this man; he fights.” Instead of firing Grant, Lincoln appointed him commander of all the Union forces in western Tennessee and northern Mississippi. Over the next three years, Grant fought many battles and won the following major victories:

- Battle of Vicksburg: Grant planned to attack Vicksburg, a Confederate stronghold in Mississippi, in the fall of 1862. The city was so heavily fortified that he bypassed it and instead conquered the capital, Jackson. Then, he moved back and attacked Vicksburg. After failing to take the city, he decided to starve it. After six weeks, the Confederate forces surrendered. Grant captured 30,000 men, and the North took control of the Mississippi river.

- Battle of Chattanooga: In November 1863, Grant, now the commander of the western forces, attacked Confederate forces besieging Chattanooga, Tennessee. After three days, Grant won the battle and freed Tennessee of Confederate forces. Grant’s victory also allowed for the invasion of the Confederacy by Northern forces.

- The Wilderness campaign: Grant became lieutenant general in early 1864, becoming just the third U.S. citizen to hold this position after George Washington and General Winfield Scott. In addition, Lincoln appointed Grant the commander of all Union forces, giving him command of more than half a million men and the chance to implement his own strategies. He stopped capturing cities and went after the major Confederate forces. This strategy proved bloody but successful. In May 1864, Grant attacked the Confederate forces, headed by General Lee himself. During the next month, Grant lost 60,000 men in Virginia’s wilderness. The battle ended in a draw. Grant’s subordinates were more successful, as General Sherman took Atlanta in the fall of 1864.

- Appomattox: After the fairly successful Wilderness campaign, Grant went back to his old strategy. He decided to slowly starve Lee’s armies, who were cooped up outside of Richmond, the capital of Virginia. Grant remained there from June 1864 to April 1865. His other generals slowly conquered the Confederacy during the same period. On April 9, 1865, General Lee surrendered to Grant. The Civil War was over.

In 1866, Grant received the highest honor the country could bestow on him: He became a full general. Only George Washington held this position before Grant. Grant’s duties were to demobilize, or discharge, the Northern military forces and supervise the process of Reconstruction.

Entering politics

Grant didn’t want to become a politician, but because of his popularity, the Republican Party insisted that he do so. President Johnson appointed him secretary of war in 1867. Grant agreed with Johnson on treating the South leniently. He resigned his position when the Senate declared that Johnson didn’t have the authority to fire his former secretary of war. (See the sidebar “How to get impeached” in the Johnson section of this chapter.) Johnson accused Grant of disloyalty, and Grant subsequently joined the Radical Republicans. He even supported impeaching Johnson. Grant’s path to the presidency was set.

President Ulysses Simpson Grant (1869–1877)

In 1868, there was no question who the Republican Party wanted to nominate for president — Grant was the unanimous choice. Grant won the general election in a landslide when he received 214 Electoral College votes to the Democratic nominee’s (Horatio Seymour, the Governor of New York) 80.

Grant, still the number-one war hero, remained popular with the U.S. public despite a horrible first term and was nominated for reelection in 1872. He won the election by a larger margin than he had in his first term.

President Grant got off on the wrong foot right away. He handed out federal jobs on the basis of family ties and friendship. He appointed more than 40 of his relatives to federal positions. Soon, scandals broke out. Many of the people Grant appointed turned out to be corrupt. Some of the major scandals of the Grant administration included:

- The secretary of war, William Worth Belnap, resigned after defrauding Native Americans out of $100,000.

- The ambassador to Brazil, James Watson Webb, received $100,000 from the Brazilian government — the Brazilian government expected him to give a favorable report of them in Washington, D.C.

- The vice president, Schuyler Colfax, resigned after he admitted to bribery during his term as Speaker of the House.

- The secretary of the navy, George Robeson, received $300,000 for giving out contracts to preferred businesses.

- The president’s private secretary, Orville E. Babcock, was implicated in the Whiskey Ring for swindling the government out of millions in liquor taxes.

One of the main tasks Grant faced was reintegrating the South into the Union. By 1870, the Ku Klux Klan — an organization of white supremacists — was active in the South, and blacks were widely denied their civil rights, including the right to vote. Grant responded with the Force Acts of 1870 and 1871, which made it a federal crime to deny a person his or her civil rights. The only time that Grant used the acts was when he destroyed the Klan in South Carolina. He left the South alone after that. Slowly, segregation and legalized racism reemerged in the former Confederacy.

Passing on a third term

Grant briefly considered running for a third term. His wife loved being first lady, and Grant wanted to please her. But the Republican Party wasn’t keen on the idea of renominating him after all the scandals that had taken place during his administration, so he withdrew his name.

After serving out his second term, Grant took his wife on a two-year trip around the world. He briefly considered becoming the candidate for the Republican ticket in 1880, but he didn’t receive enough support. So he retired from politics.

He suddenly discovered that he was broke. He had allowed his son to invest his money, and when the investments turned sour, Grant was left penniless. To make some money, he wrote his memoirs.

He finished his autobiography a week before he died from throat cancer on July 23, 1885 (at times, he smoked more than 20 cigars a day). His book became one of the finest accounts of the Civil War.

Corruption Leads to an Uncorrupt President: Rutherford Birchard Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes was one of the most honest men ever to inhabit the White House, but he was elected under a dark cloud. He was the first president to lose the presidential race and win office through massive electoral fraud. As president, Hayes fought corruption. But his most notable achievement was ending Reconstruction.

He planned to serve just one term as president because he believed it would give him the freedom to pursue policies that he thought were right. He was willing to pursue these policies, even if it meant offending his own party and the U.S. electorate.

Hayes’s early career

The controversy over slavery brought Hayes into politics. His wife was a strong Republican who opposed slavery. Hayes shared some of her views, so he joined her political party. In 1858, he became the city solicitor for Cincinnati. Shortly thereafter, the Civil War broke out.

Hayes’s men loved him because he didn’t stay behind — in a battle, Hayes would always charge first. During the next four years, Hayes was wounded four times, and he had his horse shot from under him on several occasions. One of his subordinates, future president William McKinley, said of Hayes: “His whole nature seemed to change when in battle…. He was, when the battle was once on … intense and ferocious.”

Governing Ohio

Hayes entered Congress in 1865 and supported a tough stance on Reconstruction (for more on Reconstruction, see the section, “From Poverty to the Presidency: Andrew Johnson,” earlier in this chapter). He didn’t have time to accomplish much in Congress because, in 1868, the Republican Party asked him to run for governor of Ohio. Hayes accepted and won the governorship.

Hayes’s administration in Ohio foreshadowed his presidency. He eliminated corruption and appointed state officials based on merit, not personal or party ties. He also founded Ohio State University. Throughout his life, Hayes was interested in education. He attempted to provide public education to as many students as possible — especially the poor.

Hayes ran for Congress again in 1871 and lost. Undeterred, he ran for a third gubernatorial term in Ohio in 1875 and defeated the popular incumbent Democratic governor. Suddenly the Republican Party looked at him as a possible presidential nominee.

President Rutherford Birchard Hayes (1877–1881)

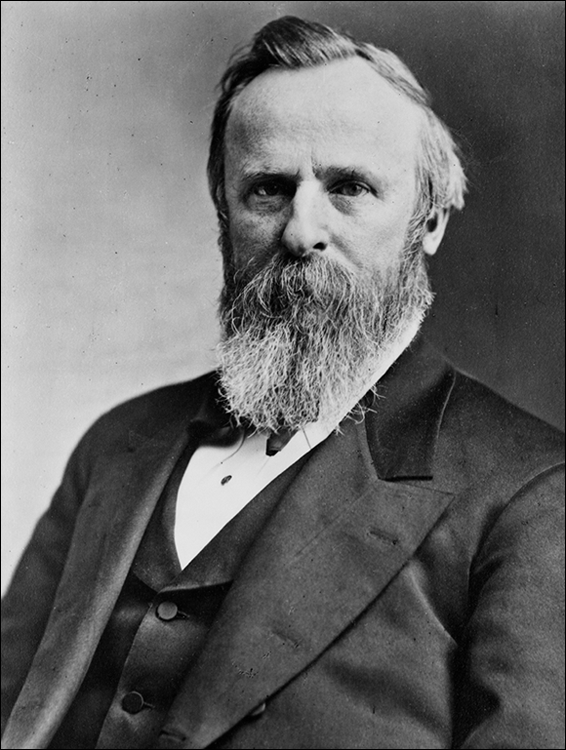

Rutherford Hayes, shown in Figure 11-3, wasn’t the frontrunner for the 1876 Republican presidential nomination. However, after all the scandals in the Grant administration, the Republican Party decided that they needed a “Mr. Clean” candidate — someone who fought corruption and was not implicated in any scandals.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 11-3: Rutherford B. Hayes, 19th president of the United States.

The election turned out to be the most controversial election in U.S. history (until the 2000 election). The Democratic nominee, Samuel Tilden, the governor of New York, won the popular vote by more than 200,000 votes. In the Electoral College, Tilden appeared to have won 203 electoral votes to Hayes’s 166.

Not surprisingly, chaos ensued in the capital. The Democrats controlled the House, and the Republicans controlled the Senate. The Republican Party knew that if the election went to the House, they would lose. So they recommended a bipartisan commission to study the election and certify the results. The Republicans arranged it so that the commission would ensure a victory for Hayes.

The Democrats were furious at the machinations of the Electoral Commission and refused to attend the inauguration. The inauguration was held in secret because the Republicans feared for Hayes’s life. Hayes received the title, “His Fraudulency.”

Ending Reconstruction

To secure the promise of the Southern states not to challenge the Electoral Commission’s ruling, the Republicans promised to end Reconstruction, appoint one Southerner to the new cabinet, and appropriate federal money to rebuild the South. President Hayes came through on the Republicans’ promise after he assumed office.

In 1877, Hayes pulled out the last Northern troops from South Carolina and Louisiana, ending Reconstruction. The Democratic Party reasserted itself and went on to control Southern politics for almost a century. The process of segregating blacks from society also started during this time. Blacks were routinely denied their civil rights, especially the right to vote.

Fighting corruption and inflation

President Hayes went after corruption as soon as he assumed the office of president. He ignored the spoils system, which handed out federal jobs based on party or family ties. He appointed the most qualified people to the positions in his administration. He further issued an executive decree, making it illegal for federal workers to work for political parties and for parties to solicit money from federal employees. The decision alienated many in both parties. In New York City, Hayes broke up a ring of federal employees working for the Republican Party. He dismissed many of the federal employees, including future president Chester A. Arthur.

Keeping his word and retiring

In 1881, Hayes kept his word and did not run for reelection. The decision seems to have been a good one. Because he alienated Republicans and Democrats alike during his presidency, he very likely would not have received the Republican nomination anyway.

As a member of Congress, Johnson was an advocate for poor whites, having been one himself. He owned five slaves and held a staunch pro-slavery view. Despite these views, he continued to be an ardent supporter of the Union, aggressively campaigning to keep the Union intact. When the Southern states seceded from the Union in 1861, Johnson was the only Southern senator to stay in Washington, D.C.; he didn’t recognize the legitimacy of the Confederacy.

As a member of Congress, Johnson was an advocate for poor whites, having been one himself. He owned five slaves and held a staunch pro-slavery view. Despite these views, he continued to be an ardent supporter of the Union, aggressively campaigning to keep the Union intact. When the Southern states seceded from the Union in 1861, Johnson was the only Southern senator to stay in Washington, D.C.; he didn’t recognize the legitimacy of the Confederacy. Andrew Johnson was the only president in U.S. history not to have a vice president and to be elected to the U.S. Senate after serving as president.

Andrew Johnson was the only president in U.S. history not to have a vice president and to be elected to the U.S. Senate after serving as president. As a slap in the face to Johnson, and especially Congress, individual Southern states ended up passing the Black Codes, which restricted former slaves’ right to testify against whites, to serve on juries, to bear arms, to hold meetings, to vote, and to own property.

As a slap in the face to Johnson, and especially Congress, individual Southern states ended up passing the Black Codes, which restricted former slaves’ right to testify against whites, to serve on juries, to bear arms, to hold meetings, to vote, and to own property. Echoing his policies, Johnson, in his 1867 message to Congress, stated that “Blacks have less capacity for government than any other race of people,” and when left to themselves show a “constant tendency to relapse into barbarism.”

Echoing his policies, Johnson, in his 1867 message to Congress, stated that “Blacks have less capacity for government than any other race of people,” and when left to themselves show a “constant tendency to relapse into barbarism.” Grant’s real name was Hiram Ulysses Grant. A mistake on his West Point application had him admitted under the name Ulysses Simpson Grant. Simpson was actually his mother’s maiden name. Grant liked the new name, so he stuck with it.

Grant’s real name was Hiram Ulysses Grant. A mistake on his West Point application had him admitted under the name Ulysses Simpson Grant. Simpson was actually his mother’s maiden name. Grant liked the new name, so he stuck with it.