Chapter 10

Preserving the Union: Abraham Lincoln

IN THIS CHAPTER

Entering politics

Entering politics

Becoming a national figure

Becoming a national figure

Winning the presidency

Winning the presidency

Starting the Civil War

Starting the Civil War

Doing away with slavery

Doing away with slavery

Abraham Lincoln ranks first in most surveys of great U.S. presidents. It doesn’t make a difference whether you ask a professor or the average U.S. citizen. Both rank Lincoln as the most successful of all U.S. presidents.

Does Lincoln deserve this honor? Certainly. Besides saving the Union, Lincoln created the modern presidency by absorbing many of the powers Congress used to possess.

Abraham Lincoln was a kind, gentle man and a true humanitarian. Had he lived to finish serving as executive officer, the process of reintegrating the Southern states into the Union might have worked better. On the other hand, one of the great misconceptions in U.S. history is that Lincoln wanted to abolish slavery. It is true that he hated the institution and considered it immoral, but at the same time, he believed that slavery was constitutional, and he pledged to maintain it in the Southern states. All he really wanted to do was to prevent the expansion of slavery into new territories.

Lincoln’s Early Political Career

Lincoln ran for the Illinois state legislature in 1832. The general store he’d been working in went out of business about a month after he declared his candidacy, so he joined the military. The Black Hawk War broke out in 1832, and Lincoln became captain of a company of militiamen, though he never saw any action.

He returned home just two weeks before the election took place. With just a few days to campaign, Lincoln lost the election badly, which didn’t surprise him. As a Whig, he figured he would have a tough time winning because the country was moving to the Democratic Party. Despite this, Lincoln had decided to run as a Whig and supported the National Republican candidate Henry Clay in 1832, who lost badly to Andrew Jackson.

After the election, Lincoln opened his own general store in New Salem. Lincoln got a break after his store went out of business. Because he was popular and well liked, he was given the job of postmaster for New Salem. The job gave him time to read. Lincoln continued his education by reading about law, politics, and the world.

Most importantly, the job of postmaster gave him the name recognition he needed to run for political office again. When he ran for the Illinois state legislature in 1834, he won — and he kept winning. He was reelected in 1836, 1838, and 1840. Soon, he was leader of the Whigs in the Illinois state legislature.

Getting ready for the national level

Abraham Lincoln used his seat in the Illinois state legislature as a springboard to national-level politics. In 1836, he spearheaded the successful effort to move the state capital of Illinois from Vandalia to Springfield.

Lincoln improved his debating skills and his political skills while serving as a legislator. His terms as a state legislator showed his skills in compromising and illuminated his stand on slavery: While he condemned the institution of slavery, he attacked the abolitionist, anti-slavery movement as extreme and dangerous to the country.

Studying law on the side

As was common at the time, the Illinois state legislature met for just one session per year — not year-round. Lincoln used his spare time to study law. He received his license to practice in 1837. That same year, he joined the John T. Stuart law firm in Springfield, Illinois, and became a successful lawyer. In 1844, he became a founding partner in the firm Logan and Lincoln. He enjoyed the law but longed for politics. By 1844, he was ready to reenter the political scene.

A Star Is Born

In 1843, Lincoln sought the nomination of the Whig party for the seventh Congressional district — one of the few safe Whig seats in Illinois. He lost. Undeterred, he tried again in 1846. This time he received the nomination and won the election. Lincoln was now a member of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Annoying everyone

In November 1846, Abraham Lincoln was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. To his great disappointment, he didn’t become one of the leaders of the body. Instead, he was one of many freshmen — newly elected members of Congress — and he held no important offices.

Then the war against Mexico started. Lincoln, like many Whigs, considered the war unjust and believed that Polk just wanted to spread slavery, so he opposed the war. In 1847, he blasted Polk on the floor of the House and accused him of inciting the war. He was correct in saying so, but nobody wanted to hear it at the time. Lincoln’s many resolutions condemning the unjust and illegal war fell on deaf ears and annoyed his constituency.

Voting his conscience on slavery

Lincoln continued to vote his conscience on other issues, including slavery. He supported the Wilmot Proviso, which outlawed slavery in any territory gained in the Mexican-American War (see Chapter 8). He introduced a bill to outlaw slavery in the capital, Washington, D.C. (The bill never made it to the floor of the House, and for that reason, it wasn’t voted on by Congress.) He further recommended a referendum on the issue by the voters of Washington, D.C., and the full compensation of slave owners who lost their slaves if the referendum passed. Despite his anti-slavery views, Lincoln believed that neither Congress nor the president had the power to abolish slavery in the Southern states, because slavery was a state matter.

- “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.”

- “Whenever I hear anyone arguing for slavery, I feel a strong impulse to see it tried on him personally.”

Lincoln abided by the Whig rules — he didn’t run for reelection, although he wanted to serve a second term. He hoped for a nice cushy job from the new Whig President Zachary Taylor, but he only received an offer for the governorship of the Oregon Territory. Lincoln rejected the offer and returned home. Within a few years, he built his law practice into the largest and most prosperous in Illinois and became known statewide.

Debating his way to national prominence

By the early 1850s, Lincoln had lost interest in politics and resigned himself to being a lawyer. When the Kansas-Nebraska Act overturned the Missouri Compromise of 1820 (see Chapter 9), Lincoln’s interest in politics was rekindled.

Lincoln opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act vehemently, believing it would lead to extending slavery into many new states. In 1854, Lincoln participated in a debate with Stephen Douglas, the sponsor of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Lincoln attacked Douglas for exporting slavery and criticized slavery as immoral.

By 1856, the Whigs had collapsed, so Lincoln joined the Republican Party. He soon became a leader in the new party that shared his anti-slavery views. His reputation was such that he was considered as a vice-presidential candidate for the Republican Party in 1856, but he lost out.

Lincoln ran for the U.S. Senate in 1858 against none other than Stephen Douglas, his debating opponent. The campaign became an instant classic. Lincoln challenged Douglas to seven debates, which attracted many voters (more than 15,000 people attended one debate) and national newspaper coverage. By election time, Lincoln was a household name not just in Illinois but throughout the United States. For the complete texts of the debates, please see The Complete Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858, edited by Paul M. Angle (University of Chicago Press).

President Abraham Lincoln (1861–1865)

The election of 1860 proved to be unique in U.S. history. Four separate candidates ran for the presidency, and all won Electoral College votes. The Democratic Party split over the issue of slavery (see Chapter 9) and ran two candidates — the Northern Democrats nominated Lincoln’s old nemesis Stephen Douglas, while the Southern Democrats ran Vice President John Breckinridge. The old Whigs, renamed “Constitutional Unionists,” nominated John Bell, who called for preserving the Union. Finally, the new Republican Party ran Abraham Lincoln on a moderate anti-slavery platform. The platform was enough for the South to proclaim that it wouldn’t accept a Lincoln victory.

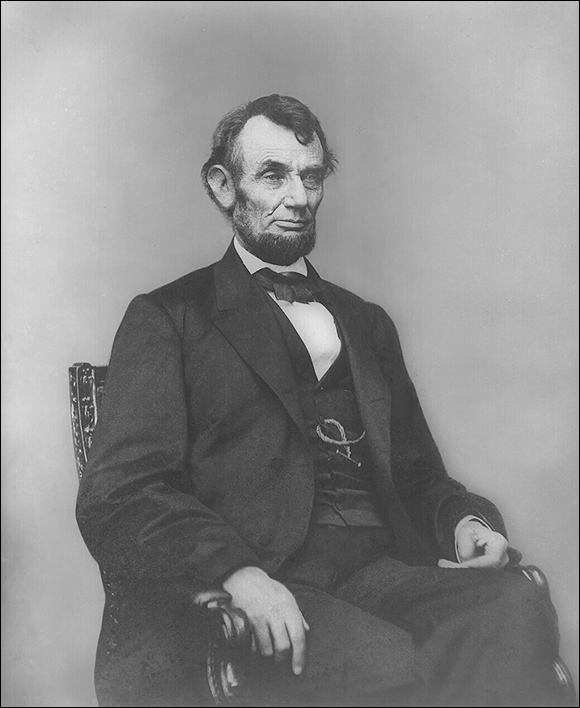

Lincoln, shown in Figure 10-1, won 180 Electoral College votes, but received only 40 percent of the popular vote. He won over 50 percent of the vote in the North and West, but received a measly 3 percent in the South. Breckinridge came in second, winning all of the Southern states, with 72 Electoral College votes. Bell and Douglas finished third and fourth, respectively.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 10-1: Abraham Lincoln, 16th president of the United States.

Dealing with secession

- Alabama

- Florida

- Georgia

- Louisiana

- Mississippi

- South Carolina

- Texas

President Buchanan’s inaction in the face of secession left Lincoln with a mess. By the time Lincoln assumed power, the Confederacy was in place and more Southern states were ready to secede.

Confronting the Confederacy

Lincoln assumed the presidency of the United States on March 4, 1861. His first order of business was to deal with the new Confederacy. He wanted to reassure the Southern states that there was no reason to secede, and he used his first inaugural address to do so.

In his inaugural address, Lincoln proclaimed that he believed that he had no right and no intention to interfere with slavery in the Southern states. In other words, Lincoln told the South that it could keep slavery — all he wanted was to prevent the institution of slavery from spreading to other states. At the same time, he took a strong stance on secession. He told the Confederacy that states didn’t have the right to secede from the Union and that he would do everything in his power to keep the Union intact. He further warned the South that the federal government wouldn’t allow the states to seize federal property — the federal government would hold it at all costs.

The Civil War

One of the headaches Lincoln inherited from his predecessor, Buchanan, was Fort Sumter, located outside of Charleston, South Carolina. Because it was a federal fort, Lincoln refused to evacuate it and hand it over to the Confederacy. Instead, he tried to reinforce it by sending additional supplies. The Confederacy, claiming the fort, subsequently attacked it and forced it to surrender. Now Lincoln had to act. He called up 75,000 militiamen from the loyal states to subdue the insurrection. While the North supported the president, the rest of the Southern states decided to join the Confederacy. Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia left the Union and joined the Confederacy.

The Civil War was about to start. Lincoln’s greatest fear was that the states bordering the South would also join the Confederacy. But to his great relief, Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland stayed in the Union.

Setting up blockades at all Southern ports: Lincoln knew that the South was very dependent on imported materials and needed to export its major good — cotton — so he tried to strangle the Southern states economically.

Blockading a foreign country is considered an act of war, and only Congress has the power to do this. Lincoln chose to act unilaterally.

Blockading a foreign country is considered an act of war, and only Congress has the power to do this. Lincoln chose to act unilaterally.- Increasing the size of the Union forces by more than 42,000 men: Only Congress has the power to fund additional troops. Lincoln decided to increase the Northern army anyway.

- Suspending the habeas corpus: Habeas corpus refers to the protection from illegal detainment that individuals receive from the federal government. Its suspension allowed the government to imprison people opposed to the war effort. Thousands of U.S. citizens were imprisoned because of their opposition to the war.

Lincoln justified his actions with the idea of presidential prerogative, meaning that, in emergencies, the executive can assume additional powers for the good of the country.

The Democrats and the Supreme Court criticized Lincoln for assuming dictatorial powers in 1861. However, by 1863, both Congress and the Supreme Court had a change of heart. They sanctioned Lincoln’s actions because he had to meet the challenges caused by the Civil War.

Lincoln breathed a sigh of relief when major European powers, such as Great Britain and France, declared their neutrality in the conflict. He knew that had a European power backed the South, it would have changed everything. Ironically, Britain was closer to the South but felt that it could not morally support a slave society.

Issuing the Emancipation Proclamation

In April 1862, Lincoln signed a bill abolishing slavery in the capital of Washington, D.C., where slavery was still legal. To appease slaveholders in the capital, he offered them monetary compensation for the loss of their slaves. Because Washington, D.C., was controlled by the federal government, Lincoln believed that he had the right to abolish slavery in the capital. But he decided he couldn’t abolish slavery in loyal slave states, such as Missouri, because he considered slavery a state matter.

In July 1862, Lincoln presented a preliminary version of the Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet. After receiving cabinet input, Lincoln revised the proclamation slightly and released it to Northern newspapers for publication in September 1862 — after the successful battle at Antietam, Maryland. Lincoln then issued a final version of the proclamation on January 1, 1863, and it subsequently went into effect.

In the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln presented an ultimatum to any state that joined the Confederacy. He referred to the Confederacy as the “rebellious states” and gave them 100 days to rejoin the Union. If they did rejoin the Union, slavery was to remain intact and protected in the 11 Southern states that made up the Confederacy. If the Confederate states failed to return to the Union, Lincoln was going to pass a declaration to end slavery in all rebellious states. He stated that he would then proclaim all slaves in the Confederacy free.

The Emancipation Proclamation did not free slaves in the slave states that remained loyal to the Union. Not until the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution was passed in 1865 (after Lincoln’s death) were slaves freed and slavery abolished in all of the United States. In Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, the parts of Virginia that would become West Virginia, and portions of Louisiana, slavery continued to exist. Instead of freeing the slaves in these areas outright, which would drive the states into Confederate hands, Lincoln encouraged a voluntary end to slavery by offering monetary compensation to slave owners.

Motivating the Confederacy

The Emancipation Proclamation didn’t have the hoped-for effect on the Confederate states. Instead of laying its arms down, the Confederacy strengthened its resolve. Now every Confederate state knew that if they lost the war, slavery would come to an end, and their way of life would change forever. The Confederacy was ready to fight to the end.

On the bright side, the four loyal slave-owning states felt reassured that the institution of slavery would continue in their states, so they remained loyal for the rest of the Civil War. In addition, the radical wing of the Republican Party, which pushed for the abolition of slavery, applauded the proclamation and started to fall in line behind Lincoln and his policies for a short period of time.

The most important effect of the Emancipation Proclamation occurred not in the United States, but in Europe. For quite some time, the Confederacy courted Great Britain and France, hoping to gain their support for the Southern cause. With the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln preempted any support from the European countries, which were opposed to slavery.

The Jacobins wanted quicker military action. They also wanted the slaves to be freed immediately. By 1863, the Jacobins were calling for the punishment of the South and its leaders. In July 1864, the Jacobins managed to push a bill through Congress that limited the right to vote on new state constitutions in the post-war South to those who had not supported the Confederacy, effectively disenfranchising most Southerners. The bill also permanently barred every major Confederate leader from voting. Lincoln opposed the bill and vetoed it. Incensed, the Jacobins withdrew their support for their own president.

Drafting soldiers: North and South

In 1863, the North instituted a draft as a direct response to the Confederacy’s establishment of a draft. All men between the ages of 20 and 45 had to serve in the military.

However, anyone who could find a substitute or pay the government $300 didn’t have to serve in the military under the terms of the Conscription Act. Many citizens saw the policy as a way for rich people to get out of serving their country. Riots in New York City were quelled by federal troops.

It was mostly volunteers who fought the Civil War. Only 6 percent of the Union forces were draftees. The numbers for the Confederacy were a bit higher — about 20 percent of the military came from draftees.

Addressing the crowds at Gettysburg

On November 19, 1863, President Lincoln delivered the most memorable speech of his career — the Gettysburg Address. Lincoln gave the address four months after the decisive battle at Gettysburg, which turned the war to the North’s favor.

Lincoln spoke at a ceremony for the dedication of a cemetery to 6,000 Northern soldiers who had died in the Battle of Gettysburg. (The soldiers were buried so hastily and in such shallow graves after the battle that their bodies became exposed again by the fall of 1863.) Senator Edward Everett, one of the great orators of his time, was scheduled to give the actual address, and Lincoln was invited at the last minute to say a few words. Senator Everett spoke for two hours to a crowd of 15,000 people, and then it was Lincoln’s turn. Lincoln spoke for only two minutes, but his words went down in history.

In the address, Lincoln stressed the ideas of liberty and equality. He tried to provide a justification for why slavery was illegal. Because the Constitution didn’t mention slavery, he relied upon the Declaration of Independence. The Declaration of Independence stated that all men were created equal. If this is true, then how could anyone justify slavery? He further proclaimed that only a Northern victory could assure the continuation of democracy and guarantee equality in the United States. The great sacrifices of the men to be buried were not in vain because their sacrifices guaranteed the future of democracy and equality in the United States.

Today the Gettysburg Address is widely considered to be one of the finest speeches ever given. This was not the case back in 1863. People forgot the speech rather quickly. It didn’t even receive prominent newspaper coverage. Everett’s speech, on the other hand, was widely acclaimed by the media. One of the few people who noticed the genius in Lincoln’s speech was Everett himself. The day after Lincoln gave the speech, Everett told him, “I wish that I could flatter myself that I had come as near to the central idea of the occasion in two hours as you did in two minutes.”

Lincoln’s Short Second Term

Lincoln was not a shoo-in to win reelection in 1864. First, the radical wing of the Republican Party, the Jacobins, was unhappy with what it considered Lincoln’s lenient policies toward the South. They especially opposed his ideas on Reconstruction. When Lincoln was up for renomination at the Republican convention, the Jacobins split from the Republican Party and nominated their own candidate, John C. Fremont. Now the Republican Party was split, undermining Lincoln’s chances against the Democrats.

In the early fall of 1864, it looked like Lincoln might lose the election. His party was split, and his Democratic opponent was well known and well respected.

Lincoln’s luck changed when General Sherman conquered Atlanta. The victory provided a major boost for Lincoln. It was the Northern victories in the Civil War and a possible end to the conflict that got Lincoln reelected — no one wanted to vote against the possible victor.

Just to ensure that the Democrats wouldn’t win, the Republican Party leaders put heavy pressure on the Jacobins and their candidate, John C. Fremont. Fremont was forced to withdraw from the race in September 1864.

With his party united again and a Northern victory looking certain, Lincoln cruised to reelection. In November 1864, Lincoln beat McClellan easily, winning 212 electoral votes to McClellan’s 21. Now it was time to focus on ending the war and beginning the process of Reconstruction.

Offering terms of surrender

Abraham Lincoln started the process of Reconstruction before the Civil War was over. As early as late 1863, he outlined his ideas on reintegrating the South into the Union.

On December 8, 1863, Lincoln issued the Proclamation for Amnesty and Reconstruction, which offered full pardons and amnesty to every Southerner, with the exception of major Confederate leaders. All the Confederate states had to do was to take an oath of loyalty to the Union. They would then receive the right to vote and the right to run their own state governments. However, they were bound by the Emancipation Proclamation and had to outlaw slavery in their states. The Confederacy rejected Lincoln’s terms.

Lincoln was disappointed with the South, but he continued to believe in generous terms of surrender. He knew that, in order to preserve the Union, he couldn’t punish the South too strongly.

Lincoln’s conciliatory tone was further reflected in an address that he gave after General Lee surrendered to the Union in April 1865. Again, Lincoln reiterated his view that a national healing must come first, and that the South should be treated leniently. Lincoln, however, would not live to put his policies into place.

Serving briefly

President Lincoln had premonitions about his death. In dreams, he saw himself as a corpse and heard people say, “Lincoln is dead.” On April 14, 1865, Lincoln and his wife attended a play, Our American Cousin, at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. A pro-Southern actor, John Wilkes Booth, shot Lincoln in the head. Lincoln died the following morning. Secretary of War Stanton put it best: “Now he belongs to the ages.”

Lincoln was a Whig in the truest sense. As a legislator, he supported business interests and constructing roads and bridges in Illinois.

Lincoln was a Whig in the truest sense. As a legislator, he supported business interests and constructing roads and bridges in Illinois. Lincoln’s resolutions condemning Polk and the Mexican-American War were called Spot Resolutions, because Lincoln alleged that the spot where Mexican troops attacked U.S. troops was actually on Mexican territory. This allegation would have justified the attack. His constituents gave him the nickname “Spotty Lincoln.”

Lincoln’s resolutions condemning Polk and the Mexican-American War were called Spot Resolutions, because Lincoln alleged that the spot where Mexican troops attacked U.S. troops was actually on Mexican territory. This allegation would have justified the attack. His constituents gave him the nickname “Spotty Lincoln.” Lincoln on slavery:

Lincoln on slavery:  Lincoln believed that he had constitutional power only to issue a military decree to free the slaves in the rebellious Southern states. The only way to end slavery in the other parts of the United States was to pass a constitutional amendment, which he urged Congress and the states to do.

Lincoln believed that he had constitutional power only to issue a military decree to free the slaves in the rebellious Southern states. The only way to end slavery in the other parts of the United States was to pass a constitutional amendment, which he urged Congress and the states to do.