Chapter 9

Working Up to the Civil War: Taylor, Fillmore, Pierce, and Buchanan

IN THIS CHAPTER

Having his term cut short: Taylor

Having his term cut short: Taylor

Becoming president by default: Fillmore

Becoming president by default: Fillmore

Pushing the country closer to civil war: Pierce

Pushing the country closer to civil war: Pierce

Letting the Union crumble: Buchanan

Letting the Union crumble: Buchanan

This chapter covers the four presidents who served in the decade before the Civil War. Zachary Taylor could have been a great president, but he died one year into his term. The other three presidents turned out to be miserable failures. With the Civil War looming, they did nothing to prevent the conflict; in fact, many of their actions contributed to the start of the war. President Fillmore destroyed his party over the issue of slavery, President Pierce openly sympathized with the South, and President Buchanan sat idly by while the Southern states seceded. None of these presidents had the backbone or the willingness to act at a time when action was desperately needed.

Trying to Preserve the Union: Zachary Taylor

When it comes to American heroes, Zachary Taylor, shown in Figure 9-1, ranks near the top of the list. During his long military career, he fought Native Americans, the British, and the Mexicans. As a military leader, he has the distinction of never being defeated in battle. Even though his enemies usually outnumbered him, he always managed to win battles somehow.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 9-1: Zachary Taylor, 12th president of the United States.

By the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, Taylor had become a national hero. His status as a hero propelled him into the presidency. If he had lived to serve his full term, a bloody civil war could have been avoided. His death, a year into his presidency, allowed for weaker presidents to follow.

Fighting Native Americans and Mexicans

Like Andrew Jackson and William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor was a military man. He spent over 40 years serving his country.

Early campaigns

Zachary Taylor became a household name in the United States during the War of 1812. While defending the Indiana territory, he faced off against a collection of Indian tribes — including the Delaware and Kickapoos — who were followers of the Shawnee chief Tecumseh. Taylor commanded only 50 soldiers, but he was able to defend Fort Harrison, a frontier outpost, against an army of 450 Native Americans.

Taylor spent the next 19 years moving from post to post. When he got a chance to fight again, his military exploits became legendary. He was in a charge of a detachment of soldiers fighting in the Black Hawk War. After pursuing the Native Americans for three months, Taylor caught up with them and defeated them soundly. His reputation grew. President Van Buren sent him to Florida to go after the Seminoles who rose against U.S. rule. Commanding over 1,100 soldiers, he pursued the Seminoles into the Everglades and finally defeated them. President Van Buren rewarded him for his victory by naming him a brigadier general in charge of the Florida district.

The Mexican-American War

By 1840, Taylor was ready for a change. So he asked for a transfer. He was sent to Louisiana, where he bought a plantation and soon owned over 100 slaves. He was ready to retire when the Mexican-American War broke out in 1845. President Polk called upon him to lead the charge one more time.

In March 1845, Congress passed a resolution annexing Texas (see Chapter 7). President Polk was interested in gaining more territory from Mexico (see Chapter 8). Taylor received orders to march his troops to Corpus Christi, Texas. In early 1846, President Polk ordered Taylor to advance into disputed territory near the Rio Grande River.

During the battle of Palo Alto, a Mexican division of around 6,000 soldiers attacked Taylor. Taylor commanded only 4,000 soldiers, but he defeated the enemy soundly. Polk and Congress promoted Taylor to major general. Next, Taylor invaded Mexico. In September 1846, he attacked and conquered Monterrey, despite being outnumbered.

In February 1847, Mexican General Santa Anna took advantage of Taylor’s situation and attacked his small army of about 5,000 men with an army of over 15,000. Taylor, who stayed right in the thick of the battle, fought the Mexican army to a standstill, and Santa Anna retreated. Taylor had not only won the battle but also the presidency. Polk’s plan misfired badly.

President Zachary Taylor (1849–1850)

Taylor’s platform was simple; he wanted to be a president of all the people. His reputation was such that he easily won the office. He carried the Electoral College with 163 votes to 127 for the Democratic nominee Lewis Cass.

Serving for just one year

President Taylor served a little over one year in office. During this time, he proved to be a capable leader, doing his best to preserve the Union.

In 1849, California and New Mexico, acquired in the Mexican-American War, applied for statehood. Both wanted to ban slavery in their territories. Taylor was okay with the decision to ban slavery in both territories because he felt slavery was a state matter.

The Southern states didn’t agree with Taylor’s views on the issue of slavery, and some Southern congressmen, including John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, threatened to secede to put pressure on the new president. Boy, did they miscalculate. Enraged, Taylor told the Southern leadership that if they seceded, he himself would lead the U.S. army against them. For Taylor, there was no compromising on this issue — had he lived long enough to finish his term in office, the Civil War might have been avoided.

On July 4, 1850, Taylor consumed cherries and frozen milk during the Fourth of July festivities in the capital. He got sick the same night and died five days later. (Poor sanitation made it risky to eat any raw fruit or dairy products during the summer. Taylor did both. He suffered severe cramps, diarrhea, and vomiting, which led to his death.) His successor, Vice President Fillmore, put the country on the path to a civil war.

Making Things Worse: Millard Fillmore

When ranking the presidents, Millard Fillmore usually falls somewhere in the bottom ten — deservedly. As president, he didn’t do much except contribute to the outbreak of the Civil War. He also did his part in destroying the Whig party, of which he was a member. He later ran for the presidency one more time as the standard bearer for the blatantly racist American Party.

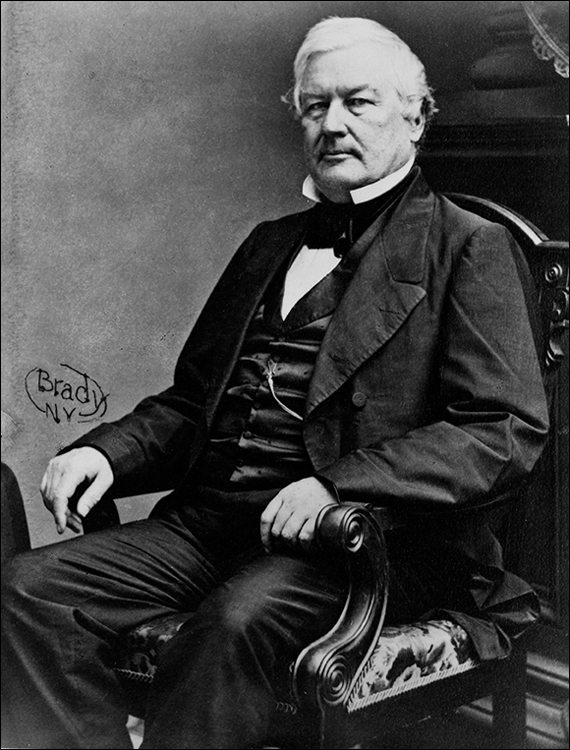

Millard Fillmore, shown in Figure 9-2, was the second vice president to succeed a president who died in office. Like John Tyler (see Chapter 7), he disagreed with his predecessor on most issues and made dramatic policy changes. Fillmore even dismissed most of Taylor’s cabinet and started from scratch.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 9-2: Millard Fillmore, 13th president of the United States.

Fillmore’s early career

In 1826, a local Mason disappeared after publishing a book on the secretive Masonic order. Citizens near Buffalo, New York, formed the Anti-Mason party. Looking for candidates, they came to Fillmore. They launched his political career when they supported his successful bid for a seat in the New York state legislature.

Fillmore expected to become the vice-presidential candidate for the Whigs in 1844, but that didn’t happen. He also lost a bid for governor of New York. Fillmore reappeared on the political scene in 1847, winning the office of state comptroller in New York.

At the Whig convention in 1848, General Zachary Taylor won the presidential nomination. As a Southern slaveholder, Taylor annoyed the anti-slavery wing of the Whig party, so it looked for a Northern candidate who opposed slavery and could win in a big state — Fillmore fit the bill. He received the vice-presidential nomination and eventually became vice president.

As vice president, Fillmore took part in discussing the major issue of the day — the slave-or-free status of new states. He tried to compromise on the issue, but President Taylor refused. War loomed on the horizon.

President Millard Fillmore (1850–1853)

President Fillmore’s first order of business was to settle the conflict over the admission of new states into the Union. Together with Henry Clay, Fillmore worked out a compromise known as the Compromise of 1850. It contained the following provisions:

- California was admitted as a free state, prohibiting slavery.

- The Utah and New Mexico territories were organized without mentioning slavery, allowing for the institution.

- A new “Fugitive Slave Law” was put into place, calling for the return of runaway slaves to their owners.

- Slavery continued to exist in Washington, D.C., although slave trading was outlawed.

- The borders of the state of Texas were defined. The state also received $10 million to pay off its state debt.

When Fillmore’s term was up in 1854, he knew he wouldn’t get the support of his own party. He attended the Whig convention, but the Whigs nominated General Winfield Scott. Scott lost the election, and the issue of slavery tore the party apart. Many of the Whigs later joined the newly established Republican Party, which advocated an anti-slavery platform.

Turning racist

In 1856, Fillmore ran for the presidency one more time. He became the candidate for the American Party, a party that opposed immigration and was anti-Catholic, anti-Black, and anti-Jewish. Fillmore won one state, Maryland, and received almost 900,000 votes in the election. After losing the election, he retired to Buffalo, New York, and served as the first chancellor for the University of Buffalo. He later opposed President Lincoln for reelection and backed President Johnson during his battles with Congress. Fillmore died in 1874. He spent his last years engaged in many civic activities.

Sympathizing with the South: Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce, shown in Figure 9-3, is another president considered to be a major failure. He may be thought of as a failure because he was such a contradiction: He was a Northern Democrat who supported slavery and the South throughout his political career.

He not only failed to resolve the slavery issue, but couldn’t achieve his political objective of territorial expansion. Added to this, no other president suffered as much in his personal life as Pierce did (see the sidebar “Facing adversity” later in this chapter), which had a great impact on his presidency. Pierce died a lonely man driven into alcoholism by a life of personal tragedy.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 9-3: Franklin Pierce, 14th president of the United States.

A Northern Democrat with a Southern soul

Throughout his political career, Franklin Pierce believed in the Constitution. He tried to follow it as closely as possible. He refused to compromise on any issues he considered unconstitutional. For this reason, he supported slavery. He considered slavery to be immoral but constitutional. He blocked any attempts to undermine the institution of slavery in the South.

Pierce’s early political career

In Congress, Pierce became a loyal supporter of Andrew Jackson. In addition, he aligned himself early on with the Southern wing of the Democratic Party, favoring slavery. In 1835, he fought a petition to end slavery in the capital, Washington, D.C. In 1836, he struck up a lifelong friendship with Jefferson Davis, the senator from Mississippi. One year later, Pierce won election to the U.S. Senate. In the Senate, Pierce continued to support Southern causes. His opponents blasted him, calling him a doughface — a term used to describe Northern congressmen who supported the South. In 1842, he resigned his Senate seat to spend more time with his family and opened a successful law practice in Concord, New Hampshire.

When the Mexican-American War broke out in 1846, Pierce became a brigadier general in the volunteer army and went to Mexico to fight.

After returning home, Pierce acted as an elder statesman, freely handing out advice. He supported the Compromise of 1850 and territorial expansion. In 1852, Pierce received an unexpected chance at the presidency.

President Franklin Pierce (1853–1857)

Trying to expand

President Pierce believed in the concept of Manifest Destiny (see Chapter 8). He tried his best to expand the United States, but he was fairly unsuccessful. His attempts included

- The Gadsden Purchase: Pierce wanted to buy a chunk of Mexico so that he could build a railroad from New Orleans to San Diego. Pierce offered $20 million to buy all of northern Mexico (most of the existing country). The Mexican government only sold him what today is southern Arizona and southern New Mexico for $15 million.

- The Ostend Manifesto: Pierce offered Spain $130 million for Cuba. The Southern states wanted Cuba because Spain was considering freeing all slaves on the island. This would have set a dangerous precedent for the U.S. South. If Spain refused to sell, Pierce was going to threaten war. The manifesto upset Northern Democrats, who feared that the South was attempting to spread slavery, and many European powers. Pierce later disclaimed the manifesto.

Addressing slavery with the Kansas-Nebraska Act

In 1854, Senator Douglas, a Northern Democrat, introduced a bill proposing the creation of the Kansas and Nebraska territories to facilitate building a railroad from his home state of Illinois.

Nebraska opted to be a free state, but Kansas was split on the issue. When Kansas voted on the issue of slavery, thousands of people from Missouri, a slave state, crossed the border to vote. Slavery won big at the ballot box.

Northerners moved to Kansas to organize an opposition to slavery and establish their own anti-slavery government. Kansas suddenly found itself with two governments. Pierce recognized the pro-slavery government. A small civil war broke out — it was referred to as Bleeding Kansas (see the section of the same name later in this chapter).

With the repeal of the Missouri Compromise, Pierce committed political suicide. His own party turned away from him, and he didn’t even attempt to run for reelection in 1856, saying, “There’s nothing left but to get drunk.”

Controversial to the end

Pierce continued to be controversial even after he retired. In 1860, he endorsed Jefferson Davis for the presidency. After Lincoln’s win that same year, Pierce became an outspoken critic of Lincoln — especially of the Emancipation Proclamation.

After his wife, Jane, and his best friend, Nathaniel Hawthorne, died in 1863 and 1864, respectively, Pierce found himself all alone. He found solace in the bottle and died a bitter man in 1869.

Failing to Save the Union: James Buchanan

James Buchanan, shown in Figure 9-4, is one of the two lowest-rated presidents in U.S. history. (See Chapter 2 for more information on presidential ratings.) His notable accomplishments before becoming president in 1857 are ignored by many.

James Buchanan loved and lived by the Constitution. He believed that, as president, he could do only what the Constitution explicitly stated. So he tolerated slavery, even though he personally opposed it. When the Southern states started to secede, Buchanan did nothing, waiting for Congress to act. Congress, split over the issue, didn’t help Buchanan with the decision — so he didn’t act. In turn, he, not Congress, received the blame for not saving the Union.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 9-4: James Buchanan, 15th president of the United States.

Buchanan’s early career

Buchanan volunteered to fight in the War of 1812, but he didn’t see any action. So he returned home and started his long political career. In 1814, he was elected to the Pennsylvania state legislature. From there, he slowly worked his way up the political ladder.

For the next half century, Buchanan served his country in many roles. Buchanan’s political jobs included

- U.S. congressman: Buchanan started his national career in 1821 when he entered the House of Representatives as a Federalist. When the party fell apart, he became a supporter of Andrew Jackson and joined the Democrats.

- Ambassador to Russia: Buchanan became ambassador to Russia in 1832 and established commercial ties with the country.

- U.S. senator: Buchanan entered the U.S. Senate in 1834 and served 12 years.

- Secretary of state: In 1845, President Polk appointed Buchanan secretary of state. Buchanan proved to be a capable leader in this role, settling the Oregon Territory dispute with Great Britain (see Chapter 8). On the other hand, he failed to buy Cuba from Spain.

- Ambassador to Great Britain: Buchanan retired after he failed to receive the 1852 presidential nomination from the Democratic Party. But President Pierce called him out of retirement and sent him to Europe in 1853. In Europe, Buchanan participated in the disastrous Ostend Manifesto (see “Sympathizing with the South: Franklin Pierce” earlier in this chapter).

President James Buchanan (1857–1861)

In 1856, the Democratic Party was split again over the issue of slavery. The Democrats couldn’t agree on a candidate for the presidency, so they started to look for a compromise candidate. They needed someone acceptable to the pro-slavery Southern wing of the party, as well as the anti-slavery Northern wing. Buchanan was a perfect fit. He was a Northerner who personally opposed slavery but believed that the institution of slavery was constitutional.

In the 1856 election, Buchanan faced a new political party. The Republican Party, which was opposed to slavery, ran a candidate for the first time in its short history. In addition, former president Fillmore ran as a third party candidate on the extreme right. Buchanan won the election easily, with the backing of all the Southern states.

Starting out with a bang

James Buchanan became president in March 1857. The infamous Dred Scott decision undermined his presidency right away.

Bleeding Kansas

Under the provisions of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Kansas could decide for itself whether to become a slave state. (See the earlier section, “Addressing slavery with the Kansas-Nebraska Act.”) By 1857, Kansas had two governments. The government in favor of slavery created the “Lecompton Constitution,” allowing slavery in the state. The anti-slavery government, headquartered in Topeka, refused to recognize the new state constitution. When Kansas applied for statehood in 1857, Buchanan accepted the pro-slavery constitution, even though it failed in a statewide popular referendum. The state of Kansas held a new referendum, and slavery failed again. Congress decided not to admit Kansas, and Buchanan took blame from both sides.

President Buchanan had stated early on that he wanted to serve only one term. When the 1860 elections came around, the question of his succession split the Democratic Party. When the Northern Democrats nominated Stephen Douglas, who opposed slavery, for president, the Southern Democrats walked out. The Southern Democrats nominated their own candidate, Vice President John Breckinridge, for the presidency. Because two Democratic candidates ran for the presidency, splitting the Democratic vote, the Republican nominee, Abraham Lincoln, was elected president.

Sitting by through secession

After Lincoln won the presidency in 1860, Buchanan just sat out the end of his term. South Carolina and other Southern states had proclaimed that a Lincoln win would lead to secession. When the states started to secede, Buchanan stood by, believing that he didn’t have the constitutional authority to prevent a state from seceding. He tried desperately to find a solution, but his compromises all failed. So he let them go.

While Zachary Taylor was drinking with friends in a tavern in Florida, a young officer approached him. The future president was not in uniform, just wearing an old coat and a straw hat. The young officer asked for Taylor to join him and openly referred to him as an “Old Codger.” The next day the officer found out who he had insulted and apologized to Taylor. The future president responded with the following remark: “Never judge a stranger by his clothes.” The saying became widely popular and is still used today.

While Zachary Taylor was drinking with friends in a tavern in Florida, a young officer approached him. The future president was not in uniform, just wearing an old coat and a straw hat. The young officer asked for Taylor to join him and openly referred to him as an “Old Codger.” The next day the officer found out who he had insulted and apologized to Taylor. The future president responded with the following remark: “Never judge a stranger by his clothes.” The saying became widely popular and is still used today. Taylor became the best-known and most popular man in the United States. Taylor fan clubs sprung up throughout the country, and the Whigs started to look at him as a possible presidential candidate. President Polk got jealous: He tried to undermine Taylor by moving most of the men under Taylor’s command to a different division and stranding him in Mexico.

Taylor became the best-known and most popular man in the United States. Taylor fan clubs sprung up throughout the country, and the Whigs started to look at him as a possible presidential candidate. President Polk got jealous: He tried to undermine Taylor by moving most of the men under Taylor’s command to a different division and stranding him in Mexico. The question of whether the new territories should be free or slave states arose right away. President Pierce and most Democrats favored the concept of popular sovereignty, which allowed the people in the new states to decide for themselves. But to do this, the Missouri Compromise, which prohibited slavery in the territories, had to be repealed. In 1854, Pierce signed the repeal of the Missouri Compromise into law, and the fat was in the fire.

The question of whether the new territories should be free or slave states arose right away. President Pierce and most Democrats favored the concept of popular sovereignty, which allowed the people in the new states to decide for themselves. But to do this, the Missouri Compromise, which prohibited slavery in the territories, had to be repealed. In 1854, Pierce signed the repeal of the Missouri Compromise into law, and the fat was in the fire. James Buchanan disliked the institution of slavery so much that he bought slaves in Washington, D.C., and took them back to Pennsylvania to set them free.

James Buchanan disliked the institution of slavery so much that he bought slaves in Washington, D.C., and took them back to Pennsylvania to set them free. Buchanan left the office of president on March 4, 1861, telling Lincoln, “My dear sir, if you are as happy in entering the White House as I shall feel in returning to Wheatland, you are a happy man indeed.”

Buchanan left the office of president on March 4, 1861, telling Lincoln, “My dear sir, if you are as happy in entering the White House as I shall feel in returning to Wheatland, you are a happy man indeed.”