Chapter 7

Forgettable: Van Buren, William Henry Harrison, and Tyler

IN THIS CHAPTER

Succeeding as a politician, failing as president: Van Buren

Succeeding as a politician, failing as president: Van Buren

Dying just one month into his term: Harrison

Dying just one month into his term: Harrison

Becoming president by default: Tyler

Becoming president by default: Tyler

It was tough to follow in the footsteps of one of the greatest presidents in U.S. history, Andrew Jackson. Sadly, Jackson’s three successors failed to duplicate his successful presidency.

Martin Van Buren was a master politician. He knew how to play the political game, manipulating issues and people, but he failed as a president.

William Henry Harrison was a great American hero. On the battlefield, he vanquished his foes. But he only lived to serve one month of his term in office.

John Tyler was an old-style southern politician and slave owner. He was almost impeached by Congress. Tyler got expelled from his party and found himself all alone when he left office.

While these three presidents served their country well before they became president, they didn’t accomplish much after they entered the White House. Their terms are utterly forgettable.

Martin Van Buren, Master of Politics

Despite a well-developed understanding of politics, Martin Van Buren’s presidency was unsuccessful. Like John Quincy Adams (see Chapter 5), Van Buren made his major contributions before he became president.

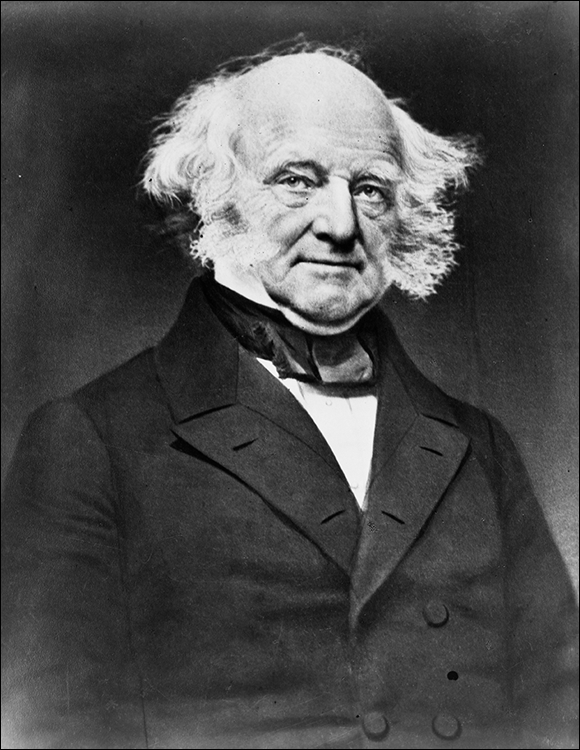

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 7-1: Martin Van Buren, 8th president of the United States.

Going from law to politics

Van Buren’s legal career got him involved in politics. He was the only Democratic-Republican lawyer in Columbia County, New York, which was heavily dominated by the Federalist Party. His legal successes gave him the reputation of being one of the best lawyers in the county. The Democratic-Republican Party took notice, backing Van Buren in his successful run for the state senate in 1812.

When Van Buren entered New York politics in 1812, the Democratic-Republican Party was split into two factions. The Clinton family headed the dominant faction; “the Bucktails” referred to whoever opposed the Clintons. (The Bucktails wore tails cut from deer on their hats at political meetings, hence the name “Bucktail.”)

Van Buren knew that he didn’t have a shot at rising to the top of New York politics in the Clinton faction, so he took over the Bucktails to oppose the Clinton family. In 1816, he won reelection to the state senate and was also appointed the attorney general for the state of New York. To Van Buren’s great dismay, DeWitt Clinton, his major political opponent, won the governorship in 1818, and Van Buren lost his job as attorney general.

Establishing a political machine

In 1821, Van Buren successfully ran for a seat in the U.S. Senate. Afraid that the Clintonians might try to stage a comeback during his absence, Van Buren established the first political machine in New York history — the Albany Regency. For the next two decades, Van Buren ran New York politics through his political machine while serving in Washington.

The concept of a political machine is Irish in origin. Irish immigrants brought the idea with them during the wave of Irish immigration that began in 1775 and lasted until 1850. By the late 19th century, political machines had control of most large industrial cities, including Chicago, Boston, and New York. Some political machines are still around today.

Politicking at the national level

When Martin Van Buren arrived on the national scene as a senator in 1821, James Monroe had just won reelection without facing any opposition, and U.S. politics were the equivalent of Democratic-Republican politics.

However, the dominant Democratic-Republican Party eventually started to fall apart. Factions developed, and Van Buren was in his element. He aligned himself with the faction that supported a weak federal government and states’ rights. In the presidential race of 1824, Van Buren became the campaign manager for Secretary of Treasury William Crawford. Van Buren won 41 Electoral College votes for his candidate, even though Crawford suffered a stroke and became paralyzed months before the election.

When Andrew Jackson lost the presidency to John Quincy Adams (see Chapter 6), Van Buren went over to the Jackson faction. Van Buren, who disagreed with Adams on many issues, saw that Jackson was the rising star in the Democratic-Republican Party.

Creating a new Democratic Party

After Van Buren won reelection to the U.S. Senate in 1827, he started gearing up for the 1828 presidential election. He decided that Jackson needed his own political party to defeat Adams this time around. Van Buren united several Democratic-Republican factions into the Democratic Party.

The Democratic Party adhered to truly Jeffersonian principles, supporting a weak national government and strong states’ rights, and opposing tariffs. In 1828, the new Democratic Party nominated Andrew Jackson for president and John Calhoun for vice president.

Van Buren knew that Jackson had to win New York to win the election. So Van Buren left the U.S. Senate to run for governor of New York in 1828. He figured that he could easily win the governorship and that his coattails would be large enough to carry the state for Jackson in the presidential race. Van Buren was right. Van Buren became governor of New York, and Jackson won the state and the presidency in a landslide.

As Van Buren had expected, Jackson never forgot who helped create the Democratic Party for him or who gave up his national political career to carry New York for him.

Playing politics

For the next few years, Van Buren held a slew of political offices, including

- Governor of New York (1829): After only two months in office, Van Buren resigned as governor of New York when Jackson appointed him secretary of state.

- Secretary of state (1829–1831): Van Buren happily accepted the office of secretary of state because he knew that the position was the first step to the presidency. He proved to be a very capable secretary of state, opening trade with Turkey and the British West Indies.

- Ambassador to Great Britain (1832): Van Buren resigned as secretary of state during a political ploy so that Jackson could fire more members of his cabinet. Van Buren left for Great Britain but returned home when the Senate refused to ratify Jackson’s choice for ambassador to Great Britain.

- Vice president of the United States (1833–1837): Van Buren became Jackson’s choice for vice president in 1832 when Jackson sacked his old vice president, John Calhoun.

Feuding with the vice president to become the vice president

The period of 1828 until 1832 proved interesting for Van Buren. He became involved in a bitter struggle with Vice President Calhoun, who was jealous of him and his close relationship with Jackson. Calhoun didn’t realize that Van Buren was an expert at playing political games. Van Buren slowly subverted his political opponent.

Van Buren defended Mrs. Eaton (“The politics of reputation” sidebar has info on the Eaton situation) and also backed Jackson when Calhoun supported nullification, or the right of a state to refuse to abide by federal law. To top it off, someone close to the president, possibly Van Buren, told Jackson that Calhoun had supported censuring Jackson back in 1818 when Jackson pursued the Seminoles in Florida and executed two British officers. (See Chapter 6 for more of Jackson’s story.)

Calhoun struck back by publicizing the struggles within Jackson’s cabinet. With Jackson angry with Calhoun, Van Buren offered to resign as the secretary of state so that Jackson could get rid of all the Calhoun supporters in his cabinet at the same time. If Van Buren were fired, it wouldn’t look like Jackson was playing politics but was just replacing a few members of his cabinet.

Jackson went along with Van Buren’s plan and named him ambassador to Great Britain. The Senate refused to ratify Van Buren, with Calhoun casting the tie-breaking vote against him. Jackson trumped Calhoun’s defection by naming Van Buren his choice for vice president in 1832. Van Buren had spun his magic and become the next vice president of the United States.

As vice president, Van Buren became Jackson’s closest advisor and friend. He backed Jackson on all issues, including his efforts to resettle Native Americans and destroy the federal bank.

When Jackson decided not to seek a third term, he insisted that Van Buren become the presidential nominee for the Democrats. Van Buren received the nomination without any opposition within the party and won the presidency easily in 1836.

President Martin Van Buren (1837–1841)

As Andrew Jackson’s successor, Martin Van Buren had very large shoes to fill. Unlike Jackson, Van Buren wasn’t a man of the people. He did not feel comfortable around people, and he had a very unappealing personality — he was constantly flip-flopping on issues and scheming against other people.

Prolonging economic chaos

Van Buren’s presidency started out disastrously, and he never recovered politically. In 1837, just after he assumed office, the Panic of 1837 started. The U.S. economy suddenly collapsed, and a worldwide recession took place.

Van Buren didn’t react to the banking disaster because he believed that the government shouldn’t intervene in the economy. The crisis lasted for three years. Finally, in 1840, at Van Buren’s urging, Congress put an independent treasury system into place, with the federal government depositing money in vaults that were located in larger cities throughout the United States.

Continuing the Trail of Tears

Van Buren continued Jackson’s policies of resettling Native Americans. The infamous Trail of Tears took place during his tenure (see Chapter 6). He sent the military to destroy the Seminoles, who rose up for the last time to fight resettlement.

Even though he opposed the institution of slavery, Van Buren did not act on his beliefs beyond refusing to admit Texas and Florida as slave states.

Battling with British Canada

During his presidency, Van Buren had a major foreign policy crisis with Canada. In 1837, Canadian citizens revolted against British rule. Many U.S. citizens were sympathetic to the uprising, so they supplied the Canadians with weapons and ammunition.

The British intercepted and destroyed a U.S. steamer carrying weapons for the Canadians, killing a U.S. citizen in the process. Enraged, some U.S. citizens raided Canada, capturing a British steamer and setting it on fire. War seemed close.

Van Buren, not wanting a war with Britain, sent the army to seal the border with Canada. The move reduced tensions, but many in the United States regarded it as a sign of weakness by their president.

In 1839, another conflict broke out with Canada. The state of Maine and the Canadian province of New Brunswick were ready to go to war over a border dispute. Both sides called out their militias. Van Buren sent the U.S. military to create a buffer between the two sides. The conflict was resolved peacefully in 1842.

Losing badly in 1840

In 1840, President Van Buren ran for reelection. He easily received the support of his own party, even though many in the United States were not very happy with him. The campaign against the Whig candidate, William Henry Harrison, proved to be a classic. Van Buren hit the campaign trail talking about issues, while the Whigs couldn’t even agree on a platform. So the Whigs ran a campaign on images instead of issues and won the election.

Staging a minor comeback and retiring

In 1848, Van Buren, now active in the anti-slavery movement, received the nomination from the Free Soil Party — a political party opposed to the extension of slavery. He received almost 300,000 votes, or 10 percent of the popular vote. Van Buren siphoned off enough Democratic votes to take the election away from the Democratic nominee, Lewis Cass.

The Founder of the Image Campaign: William Henry Harrison

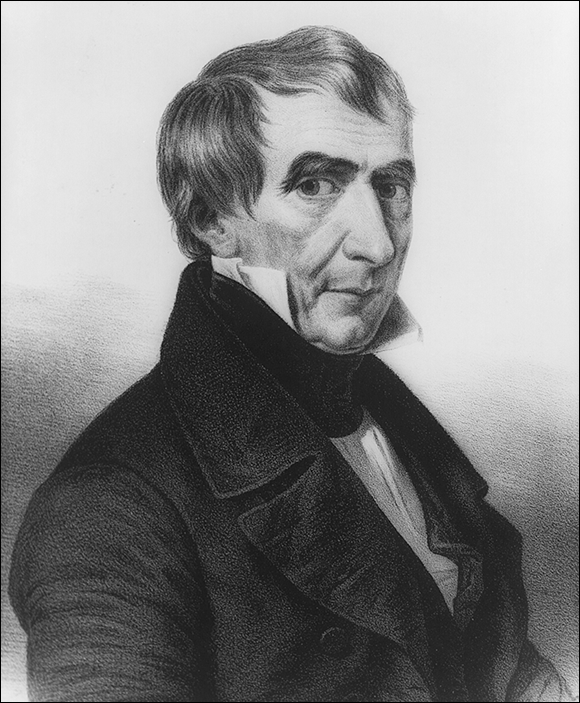

William Henry Harrison, shown in Figure 7-2, was a capable soldier and an average politician. His exploits fighting Native Americans made him a hero to the average person. He relied upon this image to win the presidency. As president, Harrison wasn’t able to accomplish much because he died right after delivering his inaugural address.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 7-2: William Henry Harrison, 9th president of the United States.

Using politics and militia against Native Americans

Like George Washington and Andrew Jackson, William Henry Harrison entered U.S. politics through the military. By 1814, he had become one of the best-known military leaders in the United States. He used his military reputation as a springboard into politics.

In 1798, Harrison, with the help of some well-connected friends, became the secretary of the Northwest Territory. Only one year later, he became the territorial delegate to the U.S. Congress for the Northwest Territory.

As a delegate to Congress, Harrison became a champion of settlers at the expense of Native Americans. He was responsible for the Land Act of 1800, which parceled up and gave Native American–held lands to white settlers at low interest rates.

As soon as Congress established the Indiana territory, Harrison became its first governor — a job he held for 12 years. As governor, he continued his onslaught on Native Americans. He got some help from President Jefferson, who told him to take all Native American lands. Jefferson also told Harrison to maintain the Native American’s friendship. Obviously, that didn’t happen.

Harrison took almost all Native American lands in the territory. When the Shawnee opposed him, he organized a militia against them. This conflict resulted in the famous Battle of Tippecanoe, where Harrison, despite losing 20 percent of his men, defeated the Shawnee and sent them fleeing to Canada. Harrison was a national hero.

In 1812, war broke out with Great Britain. Harrison, as governor of the Indiana territory, always blamed the British for inciting the Shawnee and was ready to go after them. Harrison, who was now a brigadier general in the U.S. army, won major battles in the War of 1812. He liberated Detroit, Michigan, from British occupation and defeated the British army and the rest of the Shawnee in Canada. Harrison made sure that the British didn’t invade from Canada, and this further enhanced his reputation. By 1814, everybody in the United States knew about the great “Indian fighter.”

Focusing on politics

From 1816 until 1836, Harrison held a whole slew of political offices. These offices included

- Member of the House of Representatives

- Member of the Ohio state senate

- U.S. senator

- Ambassador to Columbia

In 1836, the Whigs were desperate for a candidate to take on the ruling Democrats. They wanted someone of similar stature to Democratic President Jackson, who was about to retire. The Whigs ran three regional candidates for office. The idea behind this odd strategy was to win enough Electoral College votes to deny the Democrat, Van Buren, a majority in the Electoral College. This would throw the election to the House of Representatives, where the Whigs believed that they could win. The Whigs nominated Harrison to run in the western part of the United States. Two other regional candidates, Hugh White and Daniel Webster, ran in the South and East, respectively.

The idea backfired. Van Buren won easily in 1836. However, Harrison did so well in the West, winning 73 Electoral College votes, that he became the front-runner for the 1840 Whig presidential nomination.

President William Henry Harrison (1841–1841)

In 1839, the Whigs, desperate to win, nominated Harrison for the presidency. At the convention, the party was so split that they couldn’t agree on a party platform. So Harrison decided to run an image campaign. The party portrayed him as a common man who was born in a log cabin, like most U.S. citizens. His image became one of a hardworking, heavy-drinking commoner running against the aristocrat Van Buren. The Whigs labeled Van Buren — the son of a small tavern owner — a New York aristocrat out of touch with the common man. His nickname became “Martin Van Ruin.”

To attract southern support, former U.S. Senator John Tyler from Virginia became Harrison’s vice-presidential candidate. Harrison’s campaign slogan, “Tippecanoe and Tyler, too,” became an instant classic. Harrison’s campaign involved dragging log cabins around and providing the audience with free alcohol — a moveable party. Harrison won in a landslide, receiving 234 Electoral College votes to Van Buren’s 60.

William Henry Harrison presented his inaugural address in March 1841. It was a cold and rainy day, and Harrison refused to wear a hat and a warm winter coat. Not surprisingly, he caught a cold, which turned into pneumonia. He never recovered and died one month later.

Stepping into the Presidency: John Tyler

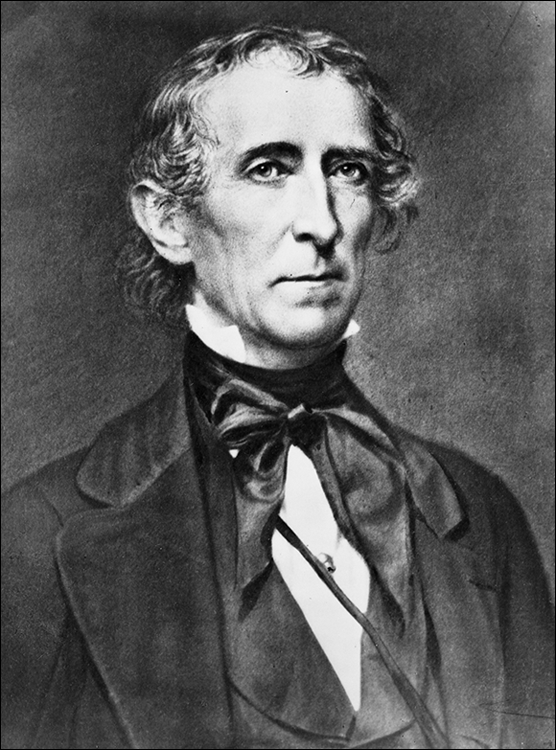

John Tyler, depicted in Figure 7-3, was the first vice president to succeed a president who died in office. Thus, he set a precedent for vice presidents to come.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 7-3: John Tyler, 10th president of the United States.

Tyler was a stubborn man who didn’t believe in compromise. He alienated not just his opposition, but also his own supporters. He was eventually kicked out of his party. After his presidency was over, he supported the Confederacy and served it as a congressman. John Tyler was the last U.S. president to favor and defend slavery.

Supporting states’ rights and slavery

As a U.S. Congressman, Tyler became a staunch supporter of states’ rights and the institution of slavery. He even opposed the Missouri Compromise of 1820 because it restricted slavery. Discouraged because he was always on the losing side of such issues as slavery, he resigned his seat in 1821.

Only four years later, Tyler became governor of Virginia. The legislature subsequently elected him to the U.S. Senate in 1827. For the next nine years, Tyler served in the Senate, basing his votes on his own beliefs and ignoring his political constituency.

But by 1833, Tyler was disenchanted with Jackson. He disagreed with Jackson’s threat to use force against South Carolina when it threatened to secede from the United States.

Tyler joined the newly created Whig party. When the Virginia legislature told him to vote to erase a previous vote to censure Jackson, he flat out refused and resigned his Senate seat. After serving two more years in the Virginia legislature, he was ready for the big time.

Balancing the ticket; becoming president

In 1840, the Whigs nominated William Henry Harrison for the presidency. To balance the ticket, they decided they needed to add a southerner. John Tyler was a perfect fit.

Because Tyler supported slavery, the Whig leadership told him to keep his mouth shut during Harrison’s image-based campaign. The objective of the campaign was to keep Harrison vague and Tyler quiet. It worked.

Tyler was getting ready to move to Washington, D.C., when he heard that President Harrison had died. A constitutional crisis loomed. Many believed that Tyler should be the acting president until a new election could be held. Tyler objected and had himself sworn in as president in April 1841. Both foes and friends went crazy, coming up with nicknames such as “His Ascendancy,” “Acting President Tyler,” “Executive Ass,” and “His Accidency.” Soon things got worse.

President John Tyler (1841–1845)

As president, Tyler didn’t change — he was still stubborn, and he refused to bargain or cooperate. His attitude made it very difficult for him to get anything accomplished, not to mention that it almost got him impeached.

Angering Congress

In 1841, Congress tried to reestablish the Bank of the United States abolished by Jackson. Tyler vetoed the bill, even though his own party proposed and passed it. Congress passed a second bill, and Tyler vetoed it again. This time, almost everyone in his cabinet resigned, his own party kicked him out, and the House of Representatives called for his impeachment.

After Tyler narrowly avoided being kicked out of office in 1843, he turned to the Democrats for help. They didn’t want anything to do with him. So Tyler formed his own party, which failed miserably. Now he was all alone, and his presidency was over. In 1844, Tyler decided to back the Democrat, James Polk, who, like him, supported the annexation of Texas.

Faring better with foreign policy

Despite the problems Tyler was having with Congress, he did succeed in foreign policy. His most notable successes include

- Settling a border dispute between Maine and Canada

- Opening trade with China

Annexing Texas

Tyler truly deserved praise for the way he handled the annexation of Texas. The U.S. Senate rejected the annexation treaty in 1844. The Constitution required a two-thirds majority to ratify treaties, which Tyler wasn’t able to get. Undeterred, Tyler tried again. He changed the rules of the game and proposed a joint resolution passed by both Houses of Congress to annex Texas — this required only a simple majority vote. It passed, and three days before Tyler left office, Texas joined the Union.

Dying a Confederate

Before 1861, Tyler tried his best to help preserve the Union. However, after listening to Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address, he decided that the Union was over. Tyler now backed the Confederacy and openly urged secession. Later that year, the people of Virginia elected him to the Confederate House of Representatives. He died of a stroke in early 1862, shortly before he could assume the office.

Van Buren, shown in

Van Buren, shown in  According to some sources, Martin Van Buren gave us one of the most commonly used terms in the English language — “okay.” One of Van Buren’s nicknames was “Old Kinderhook,” from his childhood village of Kinderhook, New York. People showed approval of Van Buren and his policies by using the term “O.K.”

According to some sources, Martin Van Buren gave us one of the most commonly used terms in the English language — “okay.” One of Van Buren’s nicknames was “Old Kinderhook,” from his childhood village of Kinderhook, New York. People showed approval of Van Buren and his policies by using the term “O.K.” After Clinton fired him, Van Buren decided that Clinton had to go. Van Buren slowly started to manipulate political meetings and conventions, packing them with his followers and using legal rules to further his political goals. For example, in 1821, his faction controlled a convention to revise the state constitution. The new constitution removed many Clintonians from office by abolishing the offices they held. Van Buren essentially had control of the state.

After Clinton fired him, Van Buren decided that Clinton had to go. Van Buren slowly started to manipulate political meetings and conventions, packing them with his followers and using legal rules to further his political goals. For example, in 1821, his faction controlled a convention to revise the state constitution. The new constitution removed many Clintonians from office by abolishing the offices they held. Van Buren essentially had control of the state. A political machine is a centralized organization that controls the political structure of a city or region by rallying its membership to vote for a particular candidate and appointing supporters to positions of power. A party boss heads the organization and controls all political offices within the machine. The machine possesses the power of patronage, or the power to appoint people to political offices. The boss doesn’t appoint opposition candidates to office, so the dominant party is truly in charge.

A political machine is a centralized organization that controls the political structure of a city or region by rallying its membership to vote for a particular candidate and appointing supporters to positions of power. A party boss heads the organization and controls all political offices within the machine. The machine possesses the power of patronage, or the power to appoint people to political offices. The boss doesn’t appoint opposition candidates to office, so the dominant party is truly in charge. In the midst of all his inactivity, President Van Buren did issue an executive order stating that nobody employed by the federal government should work more than ten hours a day.

In the midst of all his inactivity, President Van Buren did issue an executive order stating that nobody employed by the federal government should work more than ten hours a day.