Chapter 13

Influencing the World: McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, and Taft

IN THIS CHAPTER

Supporting big business and expanding the country: McKinley

Supporting big business and expanding the country: McKinley

Fighting for the little guy and getting involved in world affairs: Roosevelt

Fighting for the little guy and getting involved in world affairs: Roosevelt

Disliking the presidency but loving the Supreme Court: Taft

Disliking the presidency but loving the Supreme Court: Taft

This chapter covers three Republican presidents: One good, one great, and one failure. William McKinley was a good, capable president. He was the candidate of business, and this showed in his policies. He believed in territorial expansion, adding Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Samoan islands to the United States.

Theodore Roosevelt was one of the great presidents in U.S. history. He worked for the average person, protecting citizens against business excesses. He involved the country in world affairs and received the Nobel Peace Prize.

Finally, there’s William Howard Taft. He loved the law and never wanted to be president. His presidency wasn’t very successful. But later in life, he restored his reputation on the Supreme Court and went down in history as one of the great Supreme Court justices in U.S. history.

Discarding Isolationism: William McKinley

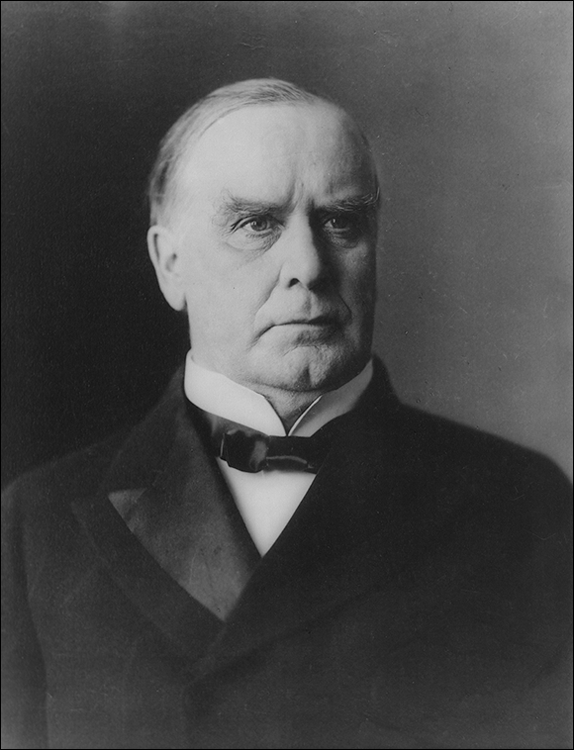

William McKinley, shown in Figure 13-1, was one of America’s more successful presidents. During his administration, he guided the country through recovery from the depression of the early 1890s. More importantly, he brought about a major change in U.S. foreign policy: The isolationism that had been in place since George Washington’s presidency finally ended. For the first time, the United States pursued an active, expansionist foreign policy. McKinley turned the country into a world power and helped it take its place among the great powers in the world.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 13-1: William McKinley, 25th president of the United States.

Being a loyal Republican

William McKinley’s political career was characterized by party loyalty and the influence of big business. As a Republican in Congress, McKinley consistently supported high tariffs to protect U.S. businesses from foreign competition. He also relied upon the support of wealthy friends to fund his political career and pay off personal debt. As president, he showed some independence but caved in to public pressure. He started the Spanish-American War in 1898, which turned out well for him, getting him reelected.

Serving in Congress

In 1876, the year Rutherford Hayes became president, McKinley was elected a member of the House of Representatives.

He served in Congress for 12 years. He distinguished himself by supporting taxes on imports to protect U.S. industry from foreign competition. In 1890, Congress passed McKinley’s greatest accomplishment, the McKinley Tariff. The tariff gave the United States the highest taxes on imports — up to 48 percent — in its history.

Governing Ohio

In 1890, McKinley lost his bid for reelection to the House of Representatives. His tariff bill alienated many farmers and middle-class workers; these groups banded together to form the coalition that defeated him.

Big business, however, didn’t forget its friend. Mark Hanna, a Cleveland, Ohio, millionaire industrialist, became McKinley’s sponsor and campaign advisor. In 1891, McKinley was elected governor of Ohio. He did a good job, building up Ohio’s infrastructure — especially its roads — and providing unemployed workers with free food during the depression of 1893. The people of Ohio reelected McKinley in 1893.

President William McKinley (1897–1901)

In 1896, Hanna thought McKinley had a shot at the Republican presidential nomination. Hanna and his friends paid for a 10,000-mile trip in 1896, where McKinley delivered 370 speeches throughout the nation campaigning for Republican candidates running for Congress. McKinley became a household name.

The money and scare tactics worked — McKinley won big. He carried all the major industrial states and received 271 electoral votes to Bryan’s 176.

Restoring prosperity

By 1897, prosperity had returned to the United States, for which McKinley received full credit. He pushed for international trade, taking the United States out of economic isolation.

Within a few years, he came to the realization that high tariffs hurt trade. By 1900, he reversed his previous position and became an advocate of free trade. At the same time, he stayed on the right side of his business friends by ignoring congressional acts designed to regulate U.S. businesses.

Branching out into international affairs

McKinley, in one of the great accomplishments of his presidency, brought the United States into the international arena. For the first time, the United States flexed its muscles and showed the rest of the world that it was ready to join the ranks of the many world powers of the 1890s. Like many U.S. citizens, McKinley believed in the concept of Manifest Destiny, or the God-given right to expand (see Chapter 8 for more on this concept).

McKinley made major strides in the area of foreign policy. He started the process of U.S. imperialism, or the annexation and domination of weaker countries. He considered imperialism good, referring to it as “benevolent assimilation.” His accomplishments in the area of imperialism included

- The Spanish-American War in 1898, which led to the annexation of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines (all parts of the Spanish colonial empire), as well as the political domination of Cuba.

- The annexation of Hawaii in 1898 after the Queen of Hawaii was overthrown in 1893 by U.S. business and U.S. troops, and the annexation of parts of the Samoan islands in 1900.

- The introduction of an open-door policy in China. This policy opened up trade with China for every country. It also resulted in the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, where 5,000 U.S. troops were part of a multinational force that fought off Chinese nationalists, who called themselves the Boxers and objected to foreign domination of their country.

Fighting the Spanish-American War

McKinley wanted to resolve the situation peacefully, but many in the United States felt that war was the way to go. The press published horrific stories about Spanish brutality, many of them false. Nevertheless, public and Congressional reaction to these sensational reports forced McKinley to act — U.S. citizens wanted to save the Cubans from the evil Spanish empire.

McKinley sent the U.S. battleship Maine to Havana, Cuba, as a show of U.S. resolve. The ship blew up in the harbor, killing 260 of the U.S. soldiers aboard. The press and the public blamed Spain, and the war was on. On April 11, 1898, McKinley asked Congress for special wartime powers. Two weeks later, Congress declared war on Spain.

In May 1898, the U.S. fleet destroyed a Spanish fleet at Manila, the capital of the Philippines. Two months later, the U.S. Navy destroyed a second Spanish fleet in Cuba.

The war was basically over. Spain agreed to negotiations, and the resulting Paris Treaty of 1898 gave the United States the Spanish colony of Puerto Rico and sold the Philippines to the United States for $20 million. More than 500,000 Filipinos were killed during an uprising against new U.S. rule.

Getting reelected and assassinated

McKinley’s foreign policy proved to be popular with the U.S. public. He won reelection easily in 1900, defeating the Democrat William Jennings Bryan decisively for a second time. The only interesting fact about the 1900 presidential race was the question of who McKinley’s vice-presidential candidate should be. His old vice president, Garret A. Hobart, died in 1899, and McKinley left it up to the Republican convention to pick his new vice president. The convention chose Teddy Roosevelt because he was a war hero with great name recognition.

On September 6, 1901, McKinley gave a speech at the Pan-American exposition in Buffalo, New York, and shook hands with the public afterwards. An anarchist by the name of Leon F. Czolgosz shot the president twice. McKinley clung to life, telling his closest advisors to be careful when presenting the news to his wife.

McKinley died from his wounds a week later after telling his doctors, “It is useless, gentlemen. I think we ought to have a prayer.” Millions of people lined up to pay their respects to one of the country’s most popular presidents as the train carrying the president’s body from New York to Ohio passed through. A month later, the federal government executed Leon Czolgosz for assassinating the president.

Vice President Roosevelt rushed back from a camping trip to be sworn in as the next president of the United States.

Building a Strong Foreign Policy: Theodore Roosevelt

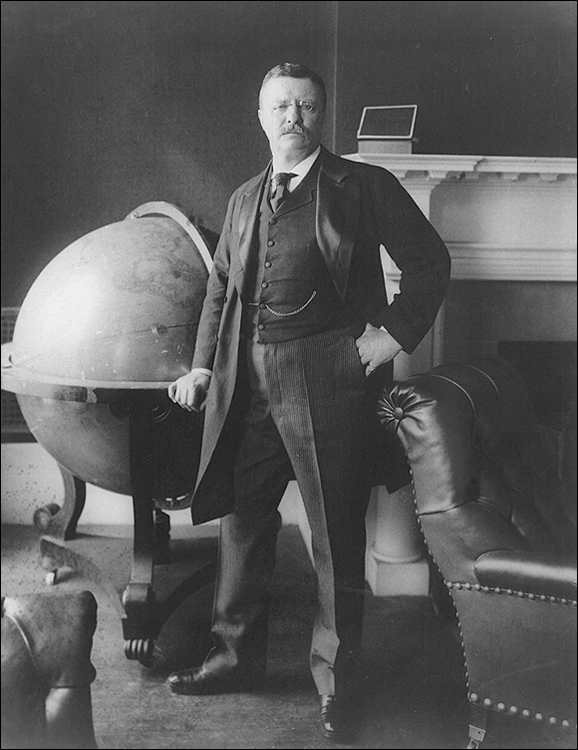

Theodore Roosevelt, shown in Figure 13-2, was one of America’s best presidents. He usually ranks in the top five of all presidents — a ranking he deserves. Roosevelt not only turned the United States into a true world power but he also began the long process of protecting the average U.S. citizen from the excesses of business. In the process, he increased the powers of the presidency, becoming the first strong president of the 20th century.

Roosevelt’s early political career

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 13-2: Theodore Roosevelt, 26th president of the United States.

Serving New York

In 1881, Roosevelt became a member of the New York state legislature. His independent streak was visible right away when he exposed a corrupt judge. He worked well with the Democratic governor, Grover Cleveland, and later served in Cleveland’s presidential administration. His affiliation with Cleveland didn’t sit well with the Republican leadership. In 1884, Roosevelt refused to run for reelection, tired of his political and personal problems (his mother and wife both died on February 14 that year), and he retired from politics.

In 1888, Roosevelt returned to Republican politics, campaigning for Benjamin Harrison. When Harrison won the presidency, he appointed Roosevelt U.S. civil service commissioner. In this position, Roosevelt opposed patronage and advocated hiring people based on merit. Roosevelt’s job as commissioner was to go after federal agencies that handed out jobs based on party ties or friendship. Roosevelt did such an excellent job that Democratic president Grover Cleveland, after winning the presidency in 1892, decided to keep him on the job even though he was a Republican.

In 1895, Roosevelt left the office to become the police commissioner for New York City. He went after corrupt police officers, and his reputation rose. Roosevelt disguised himself at night and went out on the streets to check that the police were doing an acceptable job. The public loved him for this tactic.

Returning to national politics

After the Republicans won the White House with McKinley in 1896, Roosevelt was ready for a return to the national scene. Roosevelt believed that the United States needed to become a great power. He thought that only a strong, powerful United States could survive against the great European powers. He also thought that the United States needed to expand and build up a powerful fleet to protect U.S. interests throughout the world.

Roosevelt served in McKinley’s administration as the assistant secretary of the navy. He served well and put his effort into building up the branch. During this time, Roosevelt first envisioned building a United States–controlled canal through Central America. Then, the Spanish-American War broke out. (See the section on McKinley earlier in this chapter.)

Founding the Rough Riders

When the Spanish-American War broke out, Roosevelt longed to see action. Roosevelt, who was a captain in the New York National Guard, resigned as assistant secretary and volunteered for the first U.S. volunteer cavalry, called the “Rough Riders.”

Roosevelt’s unit landed in Cuba in June 1898. He and his men saw action soon after they landed. On July 1, 1898, Roosevelt led the famous charge at San Juan Hill (Roosevelt actually charged up Kettle Hill, but the battle is usually known as the battle at San Juan Hill). He took the hill despite losing a quarter of his men. The newspapers covered the charge prominently, and Roosevelt returned home a colonel and a national hero.

Becoming governor of New York and vice president

When Roosevelt returned home, the Republican Party asked him to run for governor of New York, believing that only he could win the race for the party. They were right — Roosevelt won a narrow victory.

As governor, Roosevelt managed to alienate both business and labor: He alienated business by levying a tax on public service businesses, and labor by calling out the National Guard to put down labor unrest.

The Republicans decided to get rid of Roosevelt. They figured that there was no better way to do that than to make him the vice president — a position without real power. Roosevelt knew that taking the position very likely would end his political career, but he accepted the vice-presidential nomination anyway.

President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909)

With the assassination of President McKinley in September 1901, Teddy Roosevelt suddenly found himself president — at the age of 42, he was the youngest president in history. Roosevelt brought a unique approach to the presidency, taking members of Congress, his cabinet, and even foreign dignitaries on walking and climbing trips.

Roosevelt also managed to alienate both Republicans and Democrats fairly quickly. For example, he invited the black educator Booker T. Washington to dinner at the White House, making Washington the first black to dine in the executive mansion. This dinner invitation alienated white Southerners, who became his staunchest foes. Soon thereafter, he annoyed the Republican Party by intervening in the Pennsylvania coal strike.

Roosevelt was aware that he acted against his party’s wishes many times. He was successful because he took his case to the U.S. public. He used the presidency as a bully pulpit — a venue for getting his message across. When the public backed him, Congress begrudgingly followed.

Interfering in the coal miners’ strike

Roosevelt intervened without consulting Congress. He feared a coal shortage for the upcoming winter, so he called the mine owners to Washington, D.C., to discuss the issue. When the mine owners refused to compromise, Roosevelt threatened them. He told them that if they did not cooperate with an investigative commission, he would use federal troops to operate the mines. The owners caved in; arbitration finally took place. The next year, the mine workers received a 10 percent pay increase, and the owners accepted the nine-hour workday. Roosevelt was successful, and the public loved it.

Going after business

For Roosevelt, the public good was what mattered. He realized that many businesses were hurting the U.S. public, so he took action. He went after the Northern Securities Company, a collection of several railroad companies that joined forces to regulate prices and reduce competition. Roosevelt used the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, passed in 1890, to dissolve the trust and protect the public. Roosevelt showed how he felt about railroad owners with these words: “A man who has never gone to school may steal from a freight car; but if he has a university education, he may steal the whole railroad.”

Making his mark in foreign policy

Roosevelt’s great love was foreign policy. He didn’t believe in isolationism. Instead, he wanted the United States to be a great power that pursued an active foreign policy.

At the same time, he rejected taking control of weaker foreign nations. During his presidency, Roosevelt was more interested in resolving international disputes peacefully than going to war. He settled a dispute with Great Britain over the Alaskan-Canadian border peacefully and refused to annex Cuba and the Dominican Republic, which many in the United States supported. The only exception was the Philippines, where Roosevelt opposed Filipino nationalists fighting U.S. control of their country.

Building the Panama Canal

Roosevelt’s greatest foreign policy accomplishment was the building of the Panama Canal. The canal was one of his pet projects, and he did everything in his power to bring it about.

Roosevelt signed a treaty with Great Britain that allowed the United States to construct and then control the canal. The canal would obviously boost world trade, and under U.S. control, it could be used as an instrument in making foreign policy.

The Panamanians revolted in 1903. Roosevelt recognized the new country right away. He sent the navy to prevent Colombia from suppressing the revolt. As soon as the new Panamanian government was in power, it sold the United States a 10-mile strip of land to build the canal.

The canal was not finished until 1914. The United States retained control of the canal until President Carter signed legislation in 1977 that returned the canal to Panama by 1999 (see Chapter 22 for more on the return of the canal).

Winning reelection in 1904

In 1904, there was no question about who would win the upcoming election. Roosevelt was at the height of his popularity, and the Democratic Party nominated a virtual unknown, Alton B. Parker of New York. Roosevelt won big, carrying 336 electoral votes. He only lost the South, which was still mad at him for inviting a black to dinner at the White House (refer to the preceding section, “President Theodore Roosevelt”). Roosevelt saw the election as a mandate and pushed for even more domestic reform in his second term.

Continuing a successful foreign policy

Roosevelt picked up where he left off in the area of foreign policy. In his second term, he accomplished the following:

- The Treaty of Portsmouth: In 1905, the Japanese and Russian empires went to war. Roosevelt decided that the United States should intervene and mediate between the two countries. Both countries agreed to U.S. mediation. The Treaty of Portsmouth settled the conflict and ended the war. Roosevelt received the Nobel Peace Prize for his successful mediation between the two empires.

- The Algiers Conference: In 1905, Germany and France almost went to war over Morocco. Roosevelt called for an international conference in 1906 to settle the dispute peacefully.

- The Gentleman’s Agreement: In 1906, the city of San Francisco started to segregate its school system. The city’s program singled out Asians, especially Japanese immigrants. So Roosevelt and the Japanese empire reached an agreement in 1907, voluntarily restricting Japanese immigration to the United States.

- The Second Hague Conference: This conference, encouraged by Roosevelt, dealt with arms control and disarmament in 1907.

- The Great White Fleet: To show the rest of the world how powerful the U.S. Navy was, Roosevelt sent it around the world in 1907. The tour was especially intended to impress the Japanese, which it did.

Being progressive at home

Roosevelt continued his reformist policies back home. His second term brought many reform acts that still have an impact on the United States today. Roosevelt’s reforms include

The Meat Inspection Act (1906): This act, passed in 1906, mandated the inspection of meatpacking houses by the federal government.

Roosevelt was especially interested in the meat industry. While fighting in the Spanish-American War, he observed the poor quality of meat the soldiers consumed. Many soldiers got sick after eating the meat. When Upton Sinclair published The Jungle, a novel that details the unsanitary conditions in the meat industry in 1906, the U.S. public became outraged. Roosevelt tapped into the outrage and pushed for the successful passage of the Meat Inspection Act.

Roosevelt was especially interested in the meat industry. While fighting in the Spanish-American War, he observed the poor quality of meat the soldiers consumed. Many soldiers got sick after eating the meat. When Upton Sinclair published The Jungle, a novel that details the unsanitary conditions in the meat industry in 1906, the U.S. public became outraged. Roosevelt tapped into the outrage and pushed for the successful passage of the Meat Inspection Act.- The Pure Food and Drug Act (1906): This act prohibited the production of unsafe food, liquors, medicines, and drugs.

- The Hepburn Act (1906): This act regulated the railways and allowed the federal government to supervise the railroad industry and to set prices for railroad charges. The act was later applied to telegraph and telephone companies.

During his presidency, Roosevelt set aside 235 million acres of public lands for conservation, doubling the number of national parks. He believed that he had to protect the country’s public lands from private exploitation.

Salvaging the economy

In 1907, the Knickerbocker Bank in New York City, one of the largest and most powerful banks in the United States, collapsed. The collapse caused a widespread panic on Wall Street and among the public. Because the federal government didn’t insure banks at the time, massive withdrawals of money could have ruined them. To prevent this, Roosevelt asked a consortium of financiers, headed by J. P. Morgan, to bail out the Knickerbocker Bank. The consortium of financiers came through, buying out other financially unstable institutions and businesses, also. Congress further stabilized the situation with the passage of the Aldrich-Vreeland Act in 1908, which provided unstable banks with federal funds. The act ended the panic and avoided a recession.

Saying no to a third term

In 1908, Roosevelt faced a difficult decision. Should he run for a third term? He knew that he could easily win reelection. However, during the 1904 campaign, he pledged not to seek a third term. He honored his pledge and handpicked a successor instead. His choice was William Howard Taft. Roosevelt believed that Taft was a progressive Republican, like himself, who would continue Roosevelt’s policies. Boy, was he wrong! Roosevelt made sure that Taft won the Republican nomination. He then campaigned for him in the election. Taft won easily, and Roosevelt retired in 1909.

To allow Taft to become his own man, Roosevelt left the country and went on a safari in Africa. He went hunting and exploring. Roosevelt then went to Europe, where he was well liked and gave guest lectures at many universities. The Europeans treated him like royalty.

While vacationing in Europe, Roosevelt heard for the first time that Taft had moved away from Roosevelt’s programs. More and more progressives complained about Taft, so Roosevelt returned home.

Roosevelt went on a speaking tour to promote progressive reforms. He also called for the country to move away from enriching a few individuals and instead care for all the people of the nation.

By early 1912, Roosevelt had decided that he couldn’t live with Taft’s policies anymore. He threw his hat into the presidential ring for the Republican nomination.

Becoming a Bull Moose

Roosevelt believed that he had a good chance of receiving the Republican nomination in 1912. However, Taft’s handlers made sure that Roosevelt didn’t win. At the convention, they refused to seat pro-Roosevelt delegates. This outraged supporters of Roosevelt, and they created the Progressive Party, or the so-called “Bull Moose Party.” The Republican Party was split, which allowed the Democrat Woodrow Wilson to win the 1912 election.

Roosevelt’s campaigning paid off. In the 1912 election, he received 28 percent of the vote — over 4 million votes. He actually did better than the incumbent President Taft, who came in third in the election. Not surprisingly, the Democrat Wilson won in an electoral landslide, despite receiving only 42 percent of the popular vote.

Retiring for good

After losing in 1912, Roosevelt retired from politics. Instead, he sought out adventure abroad. In 1913, he went to Brazil to explore the Amazon. He explored what today is the Roosevelt River in the Amazon and collected many specimens that can be seen today in the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Roosevelt returned home in 1914 and spoke out against President Wilson’s early neutrality in World War I (WWI). For Roosevelt, neutrality was a sign of weakness. At first, Roosevelt didn’t take sides in WWI because he was not sure which side to support. But after the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915 (see Chapter 14), he moved to the Allied side. He even offered to create a new volunteer division and to fight in Europe. President Wilson turned him down, and although Roosevelt didn’t fight in the war, his sons did — his son Quentin died fighting in France.

By 1918, Taft and Roosevelt had made up, and the Republican Party was united. The Republicans won big in the 1918 congressional elections, and Roosevelt was expected to win the presidency easily in 1920. Fate had other plans. Roosevelt became ill and died in his sleep on January 6, 1919. Roosevelt’s son Archie sent a telegram to his brothers in Europe that read: “The Lion is dead.”

The President Who Hated Politics: William Howard Taft (1909–1913)

William Howard Taft, shown in Figure 13-3, was a unique figure in U.S. history. He never wanted to be president, and he hated politics. He lived his life by the frequently expressed motto, “Politics makes me sick.”

President Taft didn’t have the qualities of his predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt. While Roosevelt ignored Congress and went straight to the people to get backing for his programs, Taft tried to negotiate. With the Republican Party split at the time into two factions — the conservatives and the progressives — Taft managed to alienate both wings.

Taft was a capable administrator who introduced many needed reforms but received no credit for doing so. His distaste for politics cost him reelection in 1912, and that was okay with him.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 13-3: William Howard Taft, 27th president of the United States.

Taft’s early career

Taft’s legal career really began in 1887, when he became a judge on the Ohio superior court. In 1889, Taft’s public career took off. President Harrison appointed him solicitor general for the United States. In this capacity, Taft handled all federal court cases involving the federal government. He won 18 out of the 20 cases he tried. More importantly, he met his lifelong friend and sponsor, Teddy Roosevelt, who also served in the Harrison administration.

Taft returned to Ohio after only two years in office. In Ohio, he became a member of the U.S. Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, a position he loved. After serving eight years on the court in Ohio, he was ready for the Supreme Court. However, President McKinley had a different position in mind for Taft.

Governing in the Philippines

In 1900, President McKinley had a tough time dealing with the newly acquired Philippines. A bloody uprising against U.S. rule took place, and the military governor General Arthur MacArthur (the father of General Douglas MacArthur of World War II and Korea fame) used full force to oppress the Filipino population.

Taft had no interest in the Philippines. When McKinley first offered him the job of pacifying the Philippines, he refused. Only when McKinley offered Taft a position on the Supreme Court after he finished his job in the Philippines did Taft accept.

Taft disagreed with General MacArthur’s brutal treatment of the Filipino population, and he was happy to see the general resign in 1901.

In 1901, Taft became the governor of the Philippines. He did an excellent job as governor. He reconciled the country and set the foundation for the modern-day Philippines by creating a local democratic government and building roads, medical facilities, and schools. He reorganized the civil administration. He even bought 400,000 acres from the Catholic Church and distributed the land to poor Filipinos. Taft became so involved in governing the Philippines that he actually rejected two offers to become a member of the Supreme Court. By 1904, Taft impressed the new President, Roosevelt, so much that he made him secretary of war. Taft quickly became Roosevelt’s right-hand man.

Dabbling in foreign policy

As secretary of war, Taft involved himself in many diplomatic activities. Roosevelt chose him to settle disputes in Cuba and take care of the building of the canal in Panama. In addition, Taft received the task of bringing Russia and Japan, at war at the time, to the bargaining table. He succeeded, and Roosevelt won the Nobel Peace Prize. Eventually, Taft was left in charge whenever Roosevelt went on one of his many trips. According to Taft, “The president seems really to take much comfort that I am in his cabinet.”

By 1908, there was no question in the Republican Party about who would be Roosevelt’s successor. Roosevelt considered Taft a friend and someone who could continue his policies. The progressive wing of the Republican Party saw in Taft someone who would be another Teddy Roosevelt. The conservatives in the party saw in him someone who could help their cause and scale back some of Roosevelt’s policies. Everybody liked Taft and believed that he was on their side. He easily received the nomination and went on to defeat the Democratic nominee, William Jennings Bryan, without any problems.

President William Howard Taft (1909–1913)

Problems arose as soon as Taft assumed the presidency. During the campaign, Taft promised the U.S. public that he would lower tariffs, so he called a special session of Congress to make good on his campaign promise. Instead, the Conservative Republicans, representing business interests, increased tariffs on many items. Taft believed that a president should only react to Congress and not dictate policy, so he refused to veto the bill. Taft even defended the bill, disappointing many. For Taft, it went downhill from there.

Next came the Pinchot disaster. Gifford Pinchot was the head of the U.S. forestry service and one of Roosevelt’s closest friends. Pinchot falsely accused the new secretary of the interior, Richard Ballinger, of allowing private companies to exploit public lands in Alaska. Taft fired Pinchot, annoying Roosevelt and many progressive Republicans.

Beating the odds and accomplishing quite a bit

Overall, Taft’s accomplishments were impressive. But he was an administrator, not a politician, and he didn’t publicize his accomplishments, so he received no credit for his policies. Despite many setbacks, Taft accomplished quite a bit while in office, including

- The vigorous pursuit of monopolies and trusts. He actually pursued twice as many anti-trust lawsuits as the Roosevelt administration.

- The expansion of the powers of the Interstate Commerce Commission. He allowed the commission to regulate telephone, radio, and cable services.

- The addition of the 16th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States in 1913. This amendment, which was passed during the last days of Taft’s presidency, allowed the U.S. government to collect income taxes.

- The introduction of the Publicity Act in 1910. This act forced political parties to publicize the sources of their campaign funds and their subsequent expenditures.

- The setting aside of over 72 million acres of public lands for conservation.

- The introduction of the eight-hour workday for work on federal projects.

Only Taft’s foreign policy was truly a failure. He attempted to open up many regions in the world to U.S. investment. He failed in China and in the Caribbean. His greatest foreign policy triumph, the signing of a free trade agreement with Canada, failed when the Canadian population rejected the treaty in a popular vote.

Losing the presidency, gaining the Supreme Court

Taft knew that he had no chance of getting reelected in 1912. He probably would have defeated the Democrat Wilson in a two-man race, but with Roosevelt in there, he had to lose. He spent no time campaigning, so why didn’t he just withdraw from the race? It has been speculated that he was mad at his former friend Roosevelt, so he wanted to make sure that Roosevelt, running on the Bull Moose ticket, didn’t win either.

In the election, Taft received an abysmal 23 percent of the vote and carried only two states — the worst electoral showing by an incumbent president in U.S. history. After Taft happily retired in 1913, he taught law at Yale University. The students loved him. He also became an accomplished author of legal works. In 1921, his greatest wish came true. President Harding appointed him chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Taft excelled in his new position. He reformed the judicial system and also talked Congress into giving the Supreme Court its own building. He aligned himself with the conservative faction in the Supreme Court, but he mediated successfully with the more liberal justices. Taft was finally happy.

In February 1930, Taft became ill. He retired from the Supreme Court and died at home a few months later.

Fellow Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis said of Taft, “It’s very difficult for me to understand how a man who is so good as chief justice could have been so bad as president.”

McKinley had the Republican nomination sewn up. Hanna and his business friends raised $3.5 million for his campaign, basically buying the presidency. In contrast, the Democratic nominee, William Jennings Bryan, spent a measly $50,000. The Republicans flooded the country with pamphlets and speakers on behalf of McKinley. Major industrialists told their workers that if they voted for Bryan, a recession would follow, and they would lose their jobs.

McKinley had the Republican nomination sewn up. Hanna and his business friends raised $3.5 million for his campaign, basically buying the presidency. In contrast, the Democratic nominee, William Jennings Bryan, spent a measly $50,000. The Republicans flooded the country with pamphlets and speakers on behalf of McKinley. Major industrialists told their workers that if they voted for Bryan, a recession would follow, and they would lose their jobs. In 1895, a revolution against Spanish rule broke out in Cuba. The Spanish government responded brutally, sending 100,000 soldiers to suppress the uprising. Thousands of Cubans were put into reconcentration camps, where many died of starvation and disease.

In 1895, a revolution against Spanish rule broke out in Cuba. The Spanish government responded brutally, sending 100,000 soldiers to suppress the uprising. Thousands of Cubans were put into reconcentration camps, where many died of starvation and disease. The Cubans were put in “reconcentrados” or reconcentration camps. Concentration camps hold those the government believes are dangerous or a threat, whereas reconcentration camps hold people loyal and friendly to the government. The Spanish put friendlies in camps, and therefore, anyone not in a camp was a rebel, an enemy who had to be destroyed.

The Cubans were put in “reconcentrados” or reconcentration camps. Concentration camps hold those the government believes are dangerous or a threat, whereas reconcentration camps hold people loyal and friendly to the government. The Spanish put friendlies in camps, and therefore, anyone not in a camp was a rebel, an enemy who had to be destroyed. Roosevelt campaigned throughout the country. He even survived an assassination attempt during one of his campaign appearances. After being shot in the chest on the way to a campaign appearance, he went on to deliver his campaign speech, saying at one point, “Friends, I shall ask you to be as quiet as possible. I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have been shot; but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose.” He finished his speech before collapsing and being taken to a hospital.

Roosevelt campaigned throughout the country. He even survived an assassination attempt during one of his campaign appearances. After being shot in the chest on the way to a campaign appearance, he went on to deliver his campaign speech, saying at one point, “Friends, I shall ask you to be as quiet as possible. I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have been shot; but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose.” He finished his speech before collapsing and being taken to a hospital.