Chapter 16

Boosting the Country and Bringing Back Beer: Franklin D. Roosevelt

IN THIS CHAPTER

Beginning a career in politics

Beginning a career in politics

Saving the country’s economy

Saving the country’s economy

Winning a world war

Winning a world war

Getting elected to a fourth term

Getting elected to a fourth term

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, or FDR as he is referred to, is one of the best-known and most successful presidents in U.S. history. He became president at a time when the country faced a massive economic crisis — the Great Depression started in 1929, three years before he was elected. By then, the average citizen had lost faith in the ability of the capitalist system to overcome the economic crisis.

His programs restored hope, helped the economy out of a recession, and, later on, helped win a world war. Roosevelt set the foundation for modern-day government interference in the economy. He is the father of the U.S. welfare state and the large federal bureaucracy that administers it.

He guided the country through World War II (WWII) and turned the United States into a superpower by 1945. For these accomplishments, he deserves to be listed among the top five presidents of the United States.

Roosevelt’s Early Political Career

In 1910, the Democratic Party approached Roosevelt and asked him to run for the New York state senate. He had great name recognition, sharing a last name with the recent two-term president, plus he had the money to pay for his own campaign. Roosevelt narrowly won the seat.

In the New York state senate, Roosevelt turned out to be a crusader, pushing for social and economic reforms. He refused to submit to party pressure, acting more like an independent than a Democrat. Before he won reelection in 1912, Roosevelt started to support Woodrow Wilson — another Democratic reformer — which turned out to be a good political move when Wilson gave him a job.

Serving in the executive branch

After Wilson became president in 1913, he rewarded Roosevelt for his loyalty by naming him assistant secretary of the navy. Roosevelt held this position for the next seven years.

When the United States entered World War I (WWI) in 1917, Roosevelt’s job acquired more importance. As assistant secretary, he recruited people into the navy and planned military strategy. This experience came in handy 24 years later, during World War II.

In 1918, the Democratic Party approached Roosevelt and asked him to run for governor of New York. He turned them down and instead sought active duty in France. President Wilson refused to let him join the military because he considered Roosevelt too valuable as assistant secretary, but he did allow him to tour Europe to gain firsthand knowledge of the war.

Overcoming polio

In 1921, when he was 29 years old, Roosevelt went on vacation at his family’s retreat at Campobello in New Brunswick, Canada. He suddenly started to feel weak, with a fever and chills. Doctors diagnosed polio. The disease crippled him for life. For the next six years, Roosevelt underwent extensive rehabilitation in an effort to walk again. But it was all to no avail.

Roosevelt retired from politics and didn’t expect to return. Being in a wheelchair and unable to walk without crutches seemed to make a political career impossible. But with the encouragement of his wife Eleanor, Roosevelt returned to politics in 1924 when he gave the nominating speech for governor Al Smith of New York at the Democratic presidential convention. Smith lost in 1924, but he received the nomination in 1928.

Governing New York

When Al Smith received the Democratic presidential nomination in 1928, he gave up the governorship of New York State. Smith asked his friend Roosevelt to run for the position. Roosevelt was reluctant, but his wife and friends finally convinced him to become a candidate. He barely won the governorship, and he was back in public life.

As governor, Roosevelt dealt with a Republican-controlled legislature that slowed him down when he tried to implement reforms. Despite this limitation, Roosevelt provided tax cuts to farmers.

When the Great Depression hit, Roosevelt put policies in place that previewed the New Deal policies he would champion as president. For example, he established the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration, which provided help to the unemployed in New York.

Preparing for the presidency

By 1930, the Great Depression was in full swing. The people blamed President Hoover and the Republicans for the dismal economy. As a Democrat, Roosevelt had an easy time getting reelected as governor of New York.

After being reelected, Roosevelt became a viable candidate for the 1932 Democratic presidential nomination. Not only was he a great speaker who was well known to the electorate, but, as governor of New York, he also could deliver the largest state in the United States at the time.

In 1931, Roosevelt started campaigning by sending supporters out to travel the country and make a case for him. By 1932, he was the clear frontrunner. At the Democratic convention, Roosevelt was nominated on the fourth ballot. He chose John Nance Garner of Texas for his vice-presidential nominee to help shore up southern support.

Winning in 1932

After receiving his party’s nod in 1932, Roosevelt knew that he would win the presidency, because the public blamed Hoover and the Republican Party for the Great Depression. Despite the favorable situation, Roosevelt campaigned hard for a couple of reasons:

- He wanted majorities in both houses of Congress to support his policies.

- He wanted to prove to the public and himself that, despite his handicap, he could campaign effectively.

Using the campaign songs “Happy Days Are Here Again” and “Kick Out the Depression with a Democratic Vote,” Roosevelt traveled the country — mostly by train. Thousands listened to his speeches. By the time the election came around, Roosevelt won big. He won 42 of the 48 states and took the electoral vote, 472 to 59.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1933–1945)

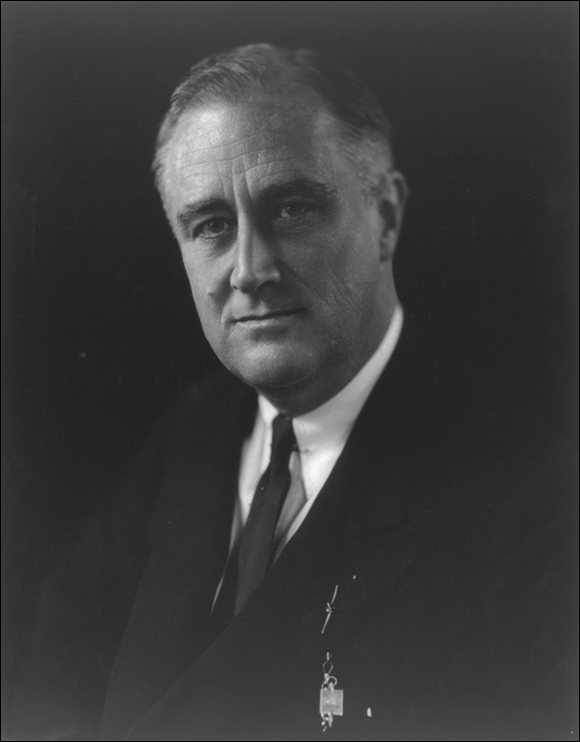

As president, Roosevelt (shown in Figure 16-1) hit the ground running. In his inaugural address, covered live on radio, he reassured the public and told people what he was about to do. He promised help for farmers and the unemployed, and, most importantly, proposed to regulate banks, brokerage firms, and the stock exchange. He declared a four-day bank holiday, when all banks nationwide were shut down, to allow the federal government to study which banks were still sound enough to reopen.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 16-1: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 32nd president of the United States.

Rescuing the economy

Roosevelt came to power at the worst possible time. In March 1933, millions of U.S. citizens were unemployed, thousands of businesses had collapsed, and the U.S. banking industry was in shambles. Not surprisingly, Roosevelt’s first order of business was to restore the public’s trust in the economic structure.

Roosevelt right away called for a special session of Congress to propose programs designed to provide rapid help to the unemployed and restore faith in the U.S. economy. His most famous New Deal programs include

- The Emergency Banking Act (1933): This act allowed for the federal government to regulate banks and restore public faith in the banking structure.

- The Beer and Wine Revenue Act (1933): This act allowed for the sale and taxation of low-alcohol beer and wine (3.2 percent or less), counter to the 18th Amendment, which banned the sale of all alcoholic beverages.

- The Economy Act (1933): This act cut the salaries of federal employees to help save the federal government money.

- The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) (1933): This administration provided federal money for states and localities to fund programs to help the poor.

- The Civilian Conservation Corps (1933): Through this program, more than 3 million young unemployed and unmarried men constructed public works projects, such as national parks and dams. These young men had to give more than 80 percent of their salary, $30 a month, to their families.

The National Industrial Recovery Act (1933): This act created the National Recovery Administration (NRA). The NRA suspended anti-trust laws temporarily and allowed price-fixing, where companies get together to set the same price for the same goods they produce, to help industry. More importantly, the act set a minimum wage and standardized working hours, and allowed workers to engage in collective bargaining.

The U.S. Supreme Court declared the NRA unconstitutional in 1935. Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act to restore parts (the minimum wage, standardized working hours, and collective bargaining) of the NRA in 1938.

The U.S. Supreme Court declared the NRA unconstitutional in 1935. Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act to restore parts (the minimum wage, standardized working hours, and collective bargaining) of the NRA in 1938.- The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) (1933): This corporation brought the federal government into the public utilities. The federal government constructed dams to generate hydroelectric power. The government then provided the power cheaply to people in Tennessee and seven surrounding states.

The Agricultural Adjustment Administration (1933): This administration had the tough order of saving U.S. farmers from financial ruin. It bought surplus agricultural goods and even paid farmers to produce less. With fewer goods available on the market, agricultural prices shot up, providing farmers with much-needed cash.

The Supreme Court declared the Agricultural Adjustment Administration unconstitutional in 1936. But it worked so well that Congress brought it back in 1938. Although terms have changed significantly, this act is the basis for the farm subsidies in place today.

- The National Housing Act (1934): This act created the Federal Housing Authority, which guaranteed home loans for up to 80 percent of their value. With the federal government backing mortgages, banks wouldn’t lose money if homeowners defaulted on their loans, so they were willing to lend more money to more home buyers. This, in turn, stimulated the housing industry. After 1937, the U.S. Housing Authority helped build low-income housing in economically depressed areas.

The Securities Exchange Act (1934): This act established the Securities and Exchange Commission. The commission, headed by FDR’s friend Joseph Kennedy (father of future president John F. Kennedy), regulated stock and bond sales. The idea behind the Securities and Exchange Commission was to make sure that the risky speculation that led to the Great Depression wouldn’t reoccur.

The Works Progress Administration (WPA) (1935): Roosevelt created this agency through an executive order. It provided jobs for the unemployed. Over four million people worked for the WPA. By 1943, the WPA had constructed 125,000 public buildings, 75,000 bridges, and 650,000 miles of roads.

- The Social Security Act (1935): This act created the country’s present social security system, the retirement system for people 65 and older. Employers and employees pay equally into it. Unemployment benefits and disability insurance were also included in the act. Finally, the federal government provided funds to the blind and qualifying dependent children.

- The Wagner Act (1935): This act guaranteed workers the right to unionize, bargain collectively, and strike.

- The Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (1937): This act, often overlooked, continues to affect U.S. presidents today. It allows U.S. presidents to negotiate their own trade agreements with foreign countries without Congressional approval. If the president and the foreign country agree, tariffs can be lowered by up to 50 percent.

- The Fair Labor Standards Act (1938): This act set a minimum wage and limited the working hours for U.S. citizens. The minimum wage was 25 cents an hour, and the workweek was 44 hours.

Fighting the Supreme Court in term two

By late 1935, the economy was on the slow road to recovery. (The best year the stock market ever had was 1931, just two years after its worst year, 1929.) Roosevelt received credit for the economic recovery. He was easily renominated at the 1936 Democratic convention. The Republicans nominated the governor of Kansas, Alf Landon, who supported most of the New Deal programs. Landon proceeded to lose to Roosevelt in a landslide.

After the election, the New Deal sparked controversy. Conservative Republicans and southern Democrats opposed the government intrusion into the economy, while many on the left of the Democratic Party hoped for even more government intervention.

In 1937, the economy began to decline again. The Supreme Court proved to be a major handicap to Roosevelt’s plans for economic recovery. The court, filled with conservative Democrats and Republicans, declared piece after piece of the New Deal unconstitutional.

Roosevelt decided to show the Supreme Court who was boss. He came up with a plan to pack the Supreme Court. Under the Constitution, the number of Supreme Court justices is not fixed: It is determined by Congress. When the justices started opposing his policies, Roosevelt proposed increasing the number of justices — nine — so that he could get enough like-minded justices on the Supreme Court to give him a majority.

With Roosevelt’s plan, the president could appoint one additional justice for each justice over the age of 70. This revision would allow Roosevelt to appoint six more justices to the court.

Even Democrats started to desert Roosevelt, refusing to go along with his court-packing plan. He suffered a bitter defeat when Congress rejected his proposal. Ironically, the threat of packing the Court was enough to convince one of the conservative justices to switch sides. In subsequent cases, the Supreme Court let New Deal programs stand.

Winning a Third Term, Facing a World War

The public punished Roosevelt and the Democratic Party for FDR’s court-packing attempt and a declining economy in the 1938 Congressional elections. Republicans increased their number of seats in Congress dramatically. It looked as if Roosevelt’s presidency was coming to an end.

Events in Europe and Asia saved Roosevelt and the Democratic Party. In Asia, Japan had invaded China, while fascism was on the rise in Europe. Foreign policy suddenly came to the forefront. The public demanded an experienced foreign policy leader for president. So Roosevelt received the nomination from the Democratic Party one more time.

The general election showed Roosevelt’s vulnerability. He won reelection, but by a much smaller margin than in 1936.

Fighting isolationism

When FDR assumed the presidency, he made major changes to U.S. foreign policy.

In Latin America, Franklin Roosevelt changed Theodore Roosevelt’s policies of open intervention (see Chapter 13) and proclaimed a Good Neighbor policy, restricting U.S. intervention in Latin American domestic affairs. Franklin Roosevelt pulled U.S. troops out of Cuba and Haiti, and signed mutually beneficial trade agreements with Latin American countries.

In 1933, Roosevelt’s secretary of state, Cordell Hull, proclaimed that the United States would stop interfering in the domestic and external affairs of other countries. Mexico soon put this new policy to the test when it nationalized all foreign oil companies. The U.S. government didn’t react, leaving U.S. oil companies to fend for themselves.

The mood of the country became isolationist, as many people wanted the United States to stay out of world affairs. Many citizens believed that U.S. intervention in World War I was wrong and that rich companies were the only beneficiaries of the war.

The acts tied Roosevelt’s hands. He wanted to help countries in Europe and Asia, but he couldn’t. Things soon changed.

Dealing with neutrality

Roosevelt’s biggest problem in 1939 was Congress, which was still isolationist in nature. Roosevelt’s hands were temporally tied. Events in Europe changed this. By 1940, France, Belgium, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Norway had fallen to Germany — Great Britain was suddenly on its own in Europe. Consensus emerged in Congress that Britain needed help. Roosevelt took advantage of this, declaring, “We are fighting to save a great and precious form of government for ourselves and for the world.”

In November 1939, shortly after WWII broke out in Europe, Roosevelt signed the Neutrality Act of 1939. This act changed previous neutrality acts by allowing the United States to export weapons to countries at war. The British Empire was the main beneficiary of this policy — a fact Roosevelt was well aware of. In turn, this change in U.S. foreign policy stimulated German submarine warfare in the Atlantic.

Helping democracy survive

By 1940, Roosevelt’s policies favoring the democracies in Europe became clearer. When France fell to the Germans in June 1940, Roosevelt changed official U.S. foreign policy to protect democracy in Europe. Instead of being neutral, the U.S. became nonbelligerent in European affairs. This change in foreign policy allowed the United States to openly support the Allies without going to war against the Axis powers. The United States was now officially able to intervene in World War II.

Roosevelt immediately delivered 50 destroyers to Great Britain to replace the heavy losses the British suffered from German submarines. The Lend-Lease Act of 1941 allowed the president to lend arms to any country that he determined to be of vital interest to U.S. national security. He promptly lent weapons to Great Britain.

Creeping closer to war

By the summer of 1941, German and Italian consulates were closed in the United States. U.S. marines had landed in Iceland to protect that country from Germany. Finally, in September 1941, Roosevelt initiated a massive tax increase (the Revenue Act of 1941) to pay for possible increased military expenditures. U.S. involvement in World War II appeared imminent.

Fighting World War II

On November 3, 1941, the U.S. ambassador to Japan, Joseph Grew, sent a warning that the Japanese were planning a surprise attack on U.S. military installations throughout the world. The warning alerted Roosevelt of a possible attack.

Three days later, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States, and the United States found itself involved in a world war.

Roosevelt turned the U.S. economy from a peace economy into a wartime economy. The president froze wages and prices for goods for the war period. He also set production goals for armaments and other goods. In one year alone, the United States produced almost 50,000 aircraft. By 1944, the United States produced more weapons and military supplies than Germany, Italy, and Japan combined. Close to 10 million men were serving in the armed forces. Women went to work in the factories to keep the war effort going.

Winning the War

By 1942, the war had turned in favor of the Allies. The U.S. Navy won major victories against the Japanese in the Pacific. The Allies invaded North Africa, and more importantly, the Russians defeated the Germans in the battle of Stalingrad. The victory signaled a possible end to the German victories on the eastern front. This allowed FDR to discuss strategies to win the war and to focus in on the postwar era.

Running and Winning One More Time

In 1944, Roosevelt faced a tough decision. Should he run for another term in office? He felt physically weak, and many believed that an unprecedented fourth term was not acceptable. On the other hand, the country was still involved in a world war, and it needed an experienced leader. So Roosevelt decided to run one more time.

During the election, Roosevelt faced Republican Thomas Dewey, the governor of New York. Roosevelt won the presidency; however, his margin of victory was even smaller than it was in 1940.

Pondering postwar problems

To avoid a possible recession, Roosevelt and Congress passed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act in 1944. The act stipulated that veterans would receive free medical treatment, low-interest loans to buy homes and businesses, and a free education. The bill today is known as the GI Bill of Rights. When the war ended in 1945, over 20 million soldiers went to college, greatly enhancing the educational level of the U.S. public.

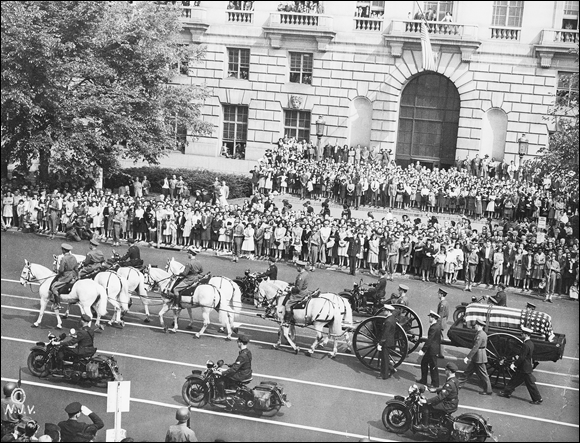

Dying suddenly

Roosevelt was exhausted when he returned home from the Yalta Conference, which ironed out the details of the end of the war, in 1945. He went to Warm Springs, Georgia, for a brief vacation. While sitting for an official presidential portrait, he suddenly complained of headaches. Two hours later, on April 12, 1945, Roosevelt died of a cerebral hemorrhage, and the country went into mourning. Figure 16-2 shows FDR’s funeral procession. Vice President Harry Truman became the new president.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 16-2: President Roosevelt’s funeral procession.

In 1920, the Democrats needed a young, energetic vice-presidential candidate to balance their fairly bland candidate for the presidency, James Cox. They picked Roosevelt. Roosevelt campaigned his heart out, but the Democratic ticket lost badly to the Republican candidate, Warren G. Harding. However, Roosevelt’s energetic style of campaigning paid off. The Democratic Party took notice of the young vice-presidential candidate.

In 1920, the Democrats needed a young, energetic vice-presidential candidate to balance their fairly bland candidate for the presidency, James Cox. They picked Roosevelt. Roosevelt campaigned his heart out, but the Democratic ticket lost badly to the Republican candidate, Warren G. Harding. However, Roosevelt’s energetic style of campaigning paid off. The Democratic Party took notice of the young vice-presidential candidate. FDR ordered a custom-made car, which allowed him to drive without having to use his feet, so that he could campaign throughout the state.

FDR ordered a custom-made car, which allowed him to drive without having to use his feet, so that he could campaign throughout the state. Traditionally, the presidential nominees didn’t speak at their party’s convention. Instead, they sent out an acceptance letter weeks after the convention finished. Roosevelt broke with tradition: He flew to Chicago, while the convention was still going on, to make his acceptance speech to the delegates in person.

Traditionally, the presidential nominees didn’t speak at their party’s convention. Instead, they sent out an acceptance letter weeks after the convention finished. Roosevelt broke with tradition: He flew to Chicago, while the convention was still going on, to make his acceptance speech to the delegates in person. He gave an unforgettable speech in which he described a new deal for the U.S. public, saying, “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people.” He promised to repeal the 18th Amendment, which prohibited the sale or distribution of alcoholic beverages, and to initiate federal public works to hire the unemployed.

He gave an unforgettable speech in which he described a new deal for the U.S. public, saying, “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people.” He promised to repeal the 18th Amendment, which prohibited the sale or distribution of alcoholic beverages, and to initiate federal public works to hire the unemployed.