Chapter 17

Stopping the Buck at Harry Truman

IN THIS CHAPTER

Working hard

Working hard

Assuming the presidency

Assuming the presidency

Struggling to be successful in his second term

Struggling to be successful in his second term

Harry Truman is one of the most underrated presidents in U.S. history. When Truman left office in 1953, many observers considered his presidency a failure. But this view has changed over time. Today, Harry Truman is ranked among the great presidents in U.S. history. People credit him with saving Western and Southern Europe from Soviet domination. He also receives credit for establishing NATO (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization), which provides for the common defense of member countries.

Truman is the president who decided that the Soviet Union needed to be stopped from expanding, and his policies achieved this objective. For this accomplishment alone, he deserves to be named one of the great presidents. Domestically, Truman was ahead of his time in the area of civil rights and welfare reform, but many of his proposals didn’t become law until the 1960s.

Truman’s Early Political Career

In 1924, Truman approached the Pendergast family, the dominant Democratic family in Missouri, about running for public office. They liked Truman, so they ran him for judge of the eastern part of Jackson County, Missouri, even though he had no background in law. Because the Pendergasts controlled state politics at the time, Truman won the position.

Truman excelled as a judge. He actually reduced the county’s debt by 60 percent while he was in charge of the infrastructure budget.

Truman lost his reelection bid, despite his solid record, when the powerful Ku Klux Klan, an organization that promotes supremacy of the white race and holds anti-Catholic and anti-Semitic views, opposed him.

The Pendergast family came to the rescue, getting Truman elected as the presiding judge for all of Jackson County in 1926. The position put Truman in control of all the county’s employees and infrastructure. Truman found the county administration in shambles, with corruption running rampant, so he set to work to reform it. He fired many of the employees who held their positions based on patronage or party ties. He even toured counties throughout the country, looking for the most effective methods of governing a county.

Truman did such a great job that he easily won reelection. By 1934, he was a well-known reformer in Missouri, famous for his honesty. He was ready to enter national politics.

Entering the Senate

In 1934, the Pendergast family approached Truman and asked him to run for the U.S. Senate. Truman accepted and ran a spirited campaign, pledging to support President Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. His campaign — and his reputation for being an honest man — helped him win a position in the Senate.

Making his mark in the Senate

After overcoming a poor start, Truman excelled in his new position. As senator, Truman was a quiet, hard-working man who soon earned his peers’ respect. During his term, he successfully passed major legislation, including the following:

- The Civil Aeronautics Act (1938): This act regulated the aviation industry by establishing the Civil Aeronautics Board and placing it in charge of U.S. airlines.

- The Transportation Act (1940): Truman chaired a subcommittee proposing major regulatory changes to the railroad industry. His recommendations resulted in the Transportation Act.

The Truman Committee (1941): This was Truman’s major accomplishment as a senator. After Truman was encouraged by his constituents to check into suspected fraud in the defense industry, the Senate assigned him the task of chairing a congressional committee to investigate.

Truman toured the country and found out that the military had handed out defense contracts for paybacks. Truman also discovered cheaply produced armaments, which didn’t work well. To top it off, Truman revealed $25 million earmarked for a nonexistent program in Canada. By the time he completed his task in 1943, he had saved the country over $15 billion, as the investigation led to many policy changes. Truman’s work was portrayed prominently by the media of the times, and he became nationally known.

Receiving the vice-presidential nomination

In 1944, everybody expected Franklin Roosevelt to run for a fourth term. The country was at war, and a change in leadership might have undermined the war effort. The big question was who Roosevelt’s running mate would be. The current vice president, Henry Wallace, was a liberal who supported union rights and civil rights, which made him unacceptable to southern Democrats. So Roosevelt went searching for someone else. He found Truman, who had supported Roosevelt’s foreign and domestic policies from the beginning.

Truman really didn’t want the job, but he didn’t dare turn down his president. So he became the vice-presidential nominee for the Democratic Party. He campaigned vigorously for the ticket and became the vice president of the United States in January 1945.

President Harry S. Truman (1945–1953)

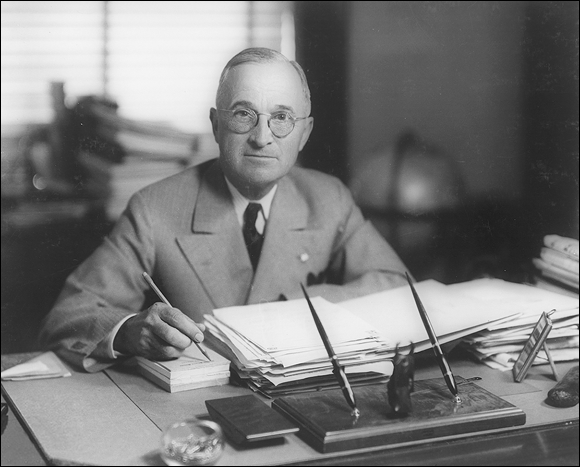

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 17-1: Harry Truman, 33rd president of the United States.

Getting up to speed on the war effort

Truman and Franklin Roosevelt were never close. Truman wasn’t privy to many of Roosevelt’s secrets and strategies. For example, Truman wasn’t aware that the United States had two atomic bombs ready. To make matters worse, Truman wasn’t informed about Allied strategy in Europe — he had never met with Russian leader Joseph Stalin or British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and he had no experience in foreign affairs.

Truman spent his first month in office being briefed by Franklin Roosevelt’s aides. His first official foreign policy decision was to hold a conference in San Francisco to establish the United Nations (see Chapter 16). He then got the Senate to approve U.S. membership.

Waging peace in Europe

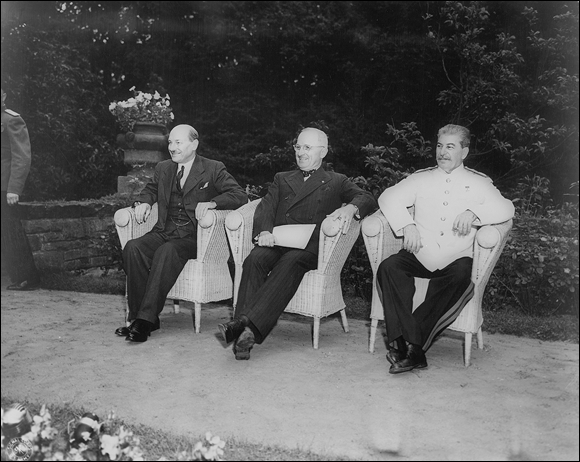

Truman became president on April 12, 1945, and World War II ended in Europe on May 8, 1945. In July, Truman traveled to Europe to attend the Potsdam Conference to discuss postwar European affairs with the major Allied leaders, Stalin and Churchill, and later Clement Atlee, who followed Churchill as prime minister of Great Britain. Figure 17-2 shows Truman, Stalin, and Atlee meeting in Potsdam, Germany.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 17-2: Atlee, Truman, and Stalin at the Potsdam Conference.

Truman was especially interested in getting the Soviet Union involved in the war with Japan. Even though the war in Europe was over, the United States was still losing close to 1,000 soldiers a day in the Pacific. Truman believed that with the help of the Soviets, the war would be over sooner rather than later.

Dropping the A-bomb

The Japanese government surrendered on August 14, 1945. World War II was finally over.

Stopping the spread of communism and recognizing Israel

When World War II came to an end in 1945, a power vacuum existed in Europe. The former great powers on the continent — Germany, France, and Great Britain — were in shambles. The Soviet Union, under the leadership of Joseph Stalin, tried to take advantage of the confusion.

The Soviet Union expanded aggressively. By 1946, it had control of most of Eastern Europe. Stalin decided to break the Yalta and Potsdam agreements, which called for holding free elections and establishing democracy in Eastern Europe; instead, he imposed communist dictatorships on Eastern European countries.

To save Greece and Turkey from Soviet control, he proposed the Truman Doctrine (see the next section). The Soviet Union, in turn, perceived Truman’s actions as aggression, and the Cold War — the ideological and political conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States — began. The wartime friendship between the United States and the Soviet Union came to an end.

Implementing the Truman Doctrine

Official U.S. foreign policy became one of containment of communism, though there was no intention to try to overthrow already-existing communist regimes. Any government threatened by communism could call upon the United States for aid.

Instituting the anti-communist Marshall Plan

Truman was also worried about Western Europe in 1947. The Communist Party became the largest political party in France. Many people flocked to it because the economic conditions in France were so bad. The Communist Party promised to end unemployment and provide for the basic needs of all. The same happened in Italy. Suddenly it looked like the communists might come to power democratically in these two major European countries. Something needed to be done.

Together with his secretary of state, George C. Marshall, Truman came up with the European Recovery Plan. This plan, also referred to as the Marshall Plan, called for rebuilding the war-torn European continent.

Marshall announced the plan in June 1947, and every Western European country accepted the offer of aid. Some Eastern European countries wanted to accept aid, but the Soviet Union prevented them from doing so. The last democratic government in Eastern Europe, Czechoslovakia, asked for aid under the Marshall Plan, but the Soviet Union intervened, destroying democracy and killing the country’s democratically elected prime minister.

Under the Marshall Plan, the United States provided Europe with over $13 billion in economic aid between 1947 and 1951.

Airlifting food to Berlin

The four victorious Allies from World War II — the United States, France, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union — divided Germany and its capital, Berlin, into four zones after their victory. Each ally received one zone to control. Great Britain was on the verge of financial collapse in 1947. The country couldn’t afford to run its zone, so the United States took it over in 1948. Later that year, the French zone fused with the U.S. zone, creating Trizonia.

With control of three zones, the United States established a new independent West German state. Currency reform took place, and Truman asked for a new, democratic constitution. Alarmed, the Soviet Union shut off all access to the western part of Berlin, which was located within the Soviet zone of occupation. The idea was simple — prevent food from getting into West Berlin and starve the Germans into submission.

Truman implemented the Berlin airlift in June 1948. For the next 11 months, the United States flew supplies and food to the city, feeding close to two million people. At one point, a U.S. plane landed in Berlin every minute of the day. By May 1949, the Soviet Union caved in. Truman won again.

Reforming the country

With the end of World War II, Truman turned his attention to reforming his own country, with a special focus on civil rights and social reform. He called his program the Fair Deal — a continuation of Roosevelt’s New Deal programs.

In the 1946 election, backlash from Truman’s policies gave the Republicans a majority in both houses of Congress — the first time since 1928. This majority proceeded to stifle Truman’s reforms for the next two years.

Fighting labor

In 1946, labor unrest broke out in the United States. From locomotive engineers to telephone mechanics, everybody seemed to be on strike. By the summer of 1946, national transportation and phone service came to a halt.

Truman didn’t respond to the labor strikes. The Republican Congress decided to show him up by passing the Taft-Hartley Act, which was designed to dramatically weaken unions in the country. Truman, a union supporter, was outraged and vetoed the bill. Undeterred, the Republican Congress, with the support of southern Democrats, overrode Truman’s veto. The act stood.

- The closed shop, which demanded that you had to be a union member to work in certain industries, was outlawed.

- Secondary strikes, where a union went on strike on behalf of another union, became illegal.

- Unions could no longer contribute money to political campaigns.

- Courts could now block strikes that jeopardized national safety.

Overall, the act greatly weakened unions in the United States. It also led to the start of their decline.

Facing opposition in 1948

In the summer of 1948, the Democratic Party was split into three factions: the Progressives on the left, the Dixiecrats on the right, and Truman somewhere in the middle. The Republican Party was unified, nominating Thomas Dewey, the governor of New York, for president. Dewey had done well against Franklin Roosevelt in 1944, and he was now the frontrunner.

Defeating Dewey in 1948

Truman received the Democratic presidential nomination, but everybody expected him to lose the election in 1948. Boy, did he prove the pundits wrong.

Truman called a special session of the Republican-controlled Congress as a political ploy. When the Republican Congress didn’t accomplish anything, Truman had his campaign issue, and he attacked the Republicans as a do-nothing party. He toured the United States by train, beginning his famous whistle-stop tour. He stopped everywhere, giving up to 16 speeches a day.

Truman gained extra support when the Soviet Union endorsed Progressive Party candidate Henry Wallace. The endorsement killed Wallace’s candidacy and sent his supporters to Truman.

When the election results came in, Truman had unexpectedly, but decisively, won by more than two million votes. He received 303 electoral votes to Dewey’s 189. The Dixiecrats carried most of the southern states.

Hating His Second Term

Truman’s second term was not nearly as successful as his first one. It was dominated by foreign policy issues and a war in Korea. The year 1949 brought one of Truman’s major successes and a dismal failure.

Losing China to communism

In 1945, a communist uprising started in China. The pro-western government of China found itself all alone. None of the major western powers supported it. Great Britain was broke, France was fighting in Indochina, and Truman didn’t consider China to be that important — his first priority was Europe. The Soviets helped their communist brethren, and by 1949, the communists were in power.

The remaining members of the pro-western government fled to Formosa and established what today is known as Taiwan. The Truman administration received the blame for not helping the anti-communist forces and thus losing China. Communist China then came to hound Truman later on in his presidency, when the United States got involved with China in Korea.

Fighting in Korea

In 1950, the Korean War broke out. Truman, haunted by the disaster in China, sent U.S. troops to defend South Korea and ignored warnings from the Chinese, who asked the United States not to invade North Korea.

However, General Douglas MacArthur did just that, which prompted China to enter the war on the North Korean side. The Chinese helped stop the advance of the United States. By 1951, the pre-war borders were restored, and the war dragged on for two more years with neither side being able to advance much.

Succeeding at home

The 1948 elections gave Truman a Democratically controlled Congress. So he again pursued his Fair Deal legislation (see “Reforming the country,” earlier in this chapter). He was more successful in passing the legislation during his second term. Major proposals that passed Congress included

- The minimum wage was increased.

- Social Security coverage was increased.

- The Public Housing Bill, providing federal money to construct public housing all over the country, was passed.

At the same time, southern Democrats and Republicans rejected Truman’s civil rights agenda. Congress refused to repeal the Taft-Hartley Act, which Truman so despised, and which had severely weakened unions.

Truman’s major domestic crisis in his second term occurred in 1952. Steel workers were ready to strike, and Truman had to make a tough decision. He was pro-union, but the country was fighting in Korea and needed steel for the war effort. So he announced that the federal government would seize the steel mills to ensure continued production. This strategy alienated unions and management alike. The Supreme Court later declared his actions unconstitutional.

Ceding to Stevenson

By the spring of 1952, Truman knew that his presidency was over. He was fairly unpopular with the U.S. public. In addition, the Republicans had found an unbeatable candidate in General Dwight D. Eisenhower. So instead of going out in defeat, Truman decided that he was done. He announced his retirement and supported the candidacy of Adlai Stevenson.

When Truman left office, his presidency seemed to be a failure. Comments such as “To err is Truman” were popular. It took time for his reputation to recover.

Truman stayed active in politics. He supported and campaigned for the Democratic presidential nominees in 1956, 1960, and 1964.

- “The trouble with Eisenhower is he’s just a coward. He hasn’t got any backbone at all.”

- “Nixon is a shifty-eyed g------ liar, and people know it. He’s one of the few in the history of this country to run for high office talking out of both sides of his mouth at the same time and lying out of both sides.”

Truman’s greatest political triumph came in the 1960s when President Johnson put many of his Fair Deal policies, rejected by Congress in the 1940s, into place.

After retiring from politics, Truman wrote his memoirs and toured the country, giving speeches at many colleges. Truman died in 1972 at the age of 88.

The local Democrats asked Truman to join the Ku Klux Klan, an organization that was popular and powerful in Missouri politics at the time. Truman refused because he didn’t want to be associated with the Klan’s anti-black and anti-Catholic views.

The local Democrats asked Truman to join the Ku Klux Klan, an organization that was popular and powerful in Missouri politics at the time. Truman refused because he didn’t want to be associated with the Klan’s anti-black and anti-Catholic views. Harry Truman always wanted to be a pianist. He would get up at 5 a.m. to practice for two hours before going to school. When he realized he was not going to make it, he changed his career plans. As president, he would often play the piano to entertain his guests.

Harry Truman always wanted to be a pianist. He would get up at 5 a.m. to practice for two hours before going to school. When he realized he was not going to make it, he changed his career plans. As president, he would often play the piano to entertain his guests. The federal government investigated Truman but found no evidence of wrongdoing on his part. When asked about his relationship with the Pendergast family, Truman said, “Three things ruin a man. Power, money, and women. I never wanted power. I never had any money, and the only woman in my life is up at the house right now.” Truman kept his job, and the people of Missouri reelected him in 1940.

The federal government investigated Truman but found no evidence of wrongdoing on his part. When asked about his relationship with the Pendergast family, Truman said, “Three things ruin a man. Power, money, and women. I never wanted power. I never had any money, and the only woman in my life is up at the house right now.” Truman kept his job, and the people of Missouri reelected him in 1940. On July 26, Truman issued the Potsdam Declaration, calling for Japan’s unconditional surrender. If the Japanese didn’t accept the terms, Truman was ready to use the atomic bomb. His military advisors told him that sending U.S. troops to invade Japan could result in the deaths of up to half a million U.S. soldiers.

On July 26, Truman issued the Potsdam Declaration, calling for Japan’s unconditional surrender. If the Japanese didn’t accept the terms, Truman was ready to use the atomic bomb. His military advisors told him that sending U.S. troops to invade Japan could result in the deaths of up to half a million U.S. soldiers. Furious, the Republicans and southern Democrats formed a coalition to block Truman’s programs. Truman decided to act unilaterally in the areas he could. As president, he was in control of the U.S. armed forces. He issued an executive order, number 9981, which desegregated the U.S. military. Discrimination against blacks serving in the U.S. military finally came to an end.

Furious, the Republicans and southern Democrats formed a coalition to block Truman’s programs. Truman decided to act unilaterally in the areas he could. As president, he was in control of the U.S. armed forces. He issued an executive order, number 9981, which desegregated the U.S. military. Discrimination against blacks serving in the U.S. military finally came to an end.