MODELLING

As stated at the beginning of Chapter 2, ‘Constructing’, models are far more assembled than sculpted, which is why this chapter is separate and also why it is relatively short. It deals with some of the exceptions, for example instances of forms for which the assemblage of cut sheet or carved block just doesn’t work, usually because in real life these forms have grown rather than been built. Forms such as trees or human figures need a different approach – that of ‘pushing a soft material around’.

Since modelling in this context is more a case of copying a predetermined shape, especially in the case of the human figure, rather than embarking on the kind of ‘free-fall’ sculptural trip experienced with an abstract form, it becomes more of an exercise in ‘guided restraint’, or ‘planned limitation’. The more ways one can find of making the armature do most of the work, or using templates to guide the modelling, the better. There is room for the fluid, spontaneous and accidental of course … but this tends to be somewhat unreliable!

Tools for modelling

The best modelling tools are our own fingers and it is surprising how much detail can be achieved with them even at a small scale. We are so used to using them on their own to manipulate things and our fingertips are especially acute in their sense of pressure. As soon as we have something in our hand, such as a tool, we lose a lot of that control and sensitivity and craftspeople might spend a lifetime trying to bring it back. However, for modelling figures in 1:25 scale, for example, something is needed to impress more detail than the fingers can. The simplest and cheapest option would be to modify some cocktail sticks and coffee stirrers using a scalpel and fine sandpaper. It is useful, for example, to have a blunt or rounded end in addition to a sharp one, also both a flat and a round-ended spatula shape. Needle files (intended for fine metalwork) also make good modelling tools, but only when using a non-sticky material such as polymer clay, otherwise they will be rendered useless for anything else.

Serious modellers may want to invest in some professional modelling tools or spend a bit more time customizing their own. In the former case, it is better to have some standard clay modelling tools (for initial work and larger effects), together with a few dental modelling tools. Particularly useful is the type of clay modelling tool composed of a fixed wire loop, invaluable for removing rather than just displacing clay.

Modelling materials

The two modelling materials featured in this chapter are Super Sculpey (a polymer clay) and Milliput (an epoxy putty). They are, between them, fully representative and there may be no need for anything else. Space is confined in this chapter to describing techniques rather than materials, so more about the materials (together with some alternatives) can be found in the ‘Modelling’ section of the Directory of Materials.

Example 1: modelling figures

The challenge of figure modelling generally tends to separate the sculptors from the designers, although I am not suggesting that the two are mutually exclusive. But those who enjoy using material to create form will usually like it, whereas those for whom the model is merely the necessary means to a larger end will probably not.

If one is trying to do the job properly, and irrespective of the materials that are going to be used to create the figure, one has to start by at least mapping out the essentials of the figure in a drawing. This should include both a frontal and a side view and these should be drawn in the same scale and aligned with each other. It is much easier (as with model furniture) to make these drawings in a larger scale first and then reduce them to the final size. Both sets of drawings can be referred to while working; the larger showing more detail and the smaller defining the size.

Architectural constructions can be assisted by a variety of mechanical means but the more organic components can only be modelled by hand. Charlotte Hern modelled these façade elements using the modelling materials Milliput and Sculpey. Photo: Rachel Waterfield

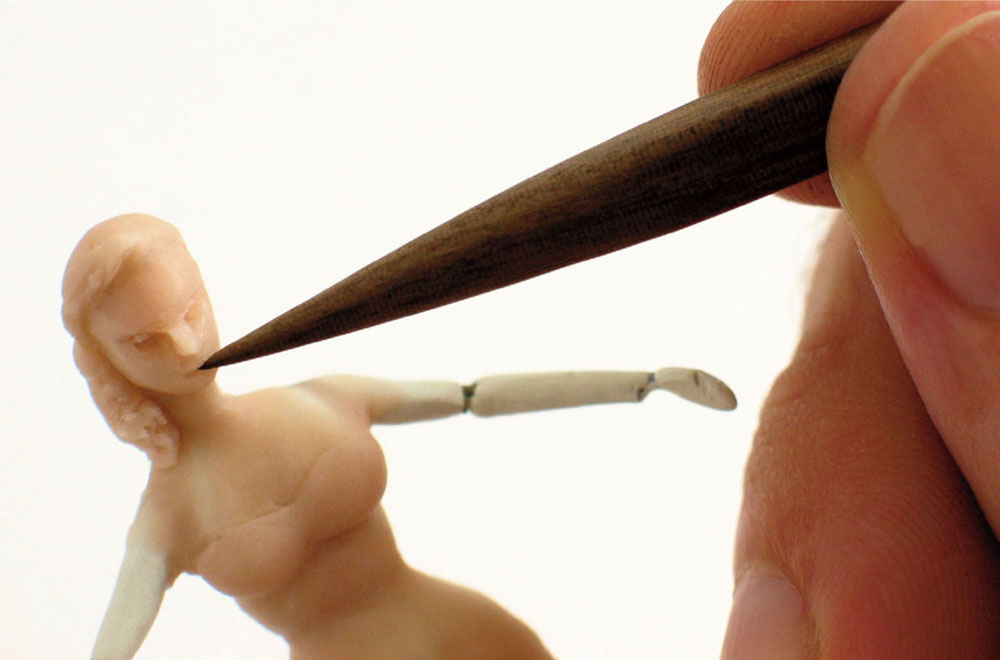

These tools have been hand-made out of a strip of walnut. The wood is hard and durable, but easy to carve and sand (tools made by Astrid Bärndal).

The most versatile material for the purpose (and for almost any small-scale modelling purpose) is a polymer clay called Super Sculpey, because of the ease with which it can be worked. Sculpey is already a film-industry standard for figure maquettes because of its consistency and relative price. It has the softness and elasticity of plasticine when kneaded between the fingers, but without the annoying tendency of plasticine to stick to the fingers when warmed too much. All polymer clays have a very similar composition and can even be mixed with each other. The manufacturers of polymer clays (Sculpey, FIMO, Cernit and so on) recommend that their products are baked in a domestic oven in order to harden them. This is a simple process involving relatively low temperatures, but almost any source of sustained heat will have an effect (the examples in this chapter were all hardened using a heat gun). Oven-baking can get tricky if the oven is inconsistent. Tests should always be done first to establish the correct setting. (Take small pieces of clay and roll one paper-thin, the next a bit thicker and so on, up to around 25mm thick. Bake these in the oven together for about fifteen minutes at the recommended temperature of 130°C. Examine the results when cooled.)

Another virtue of Super Sculpey is that the same piece can be baked over again without further effect (provided that the temperature and baking time remain reasonable). This means that a form can be modelled in stages and each stage can be hardened before applying the next. This solves the problem that often occurs when modelling something soft, that of pushing the form out of shape while trying to model details on top. It also solves the equally frustrating problem of where to hold a small form while completing another part of it. This may not be an issue in conventional sculpture where the size of the figure dictates a rigid armature on a fixed base, but it is difficult to work on a small-scale figure in this way. It needs to be handheld to get to every part.

1. Before modelling can begin a wire skeleton or armature has to be made, even for figures at 1:25 scale. One method for producing a versatile and accurate form of armature in soldered brass is detailed in the previous chapter. These basic armature constructions (one for a typical male, another for a female) can be bent into any position to suit. A good armature is not just a support to stop the clay sagging – it should also be a proportional reference, a sculpting guide, an indication of how far to go and where to stop. Getting the armature right constitutes perhaps more than 50 per cent of the effectiveness of the figure.

Stages in figure modelling. The brass armature, the halfway mannequin stage and the first layer of Sculpey

2. Instead of working directly on the armature with Sculpey and modelling the figure in one go, a thin mannequin is first made using Milliput. This is an epoxy putty mixed in two equal parts which allows about forty minutes of working time under normal conditions. Milliput is much stickier than Sculpey, so it can be used to coat the metal armature firmly (see the Directory of Materials for a fuller account of Milliput). Once set, it will provide a better base for the detailed modelling in Sculpey and it will also withstand the temperature of 130°C required to harden polymer clay. Unless you have a clear and fixed idea for the pose of the figure, it is best to keep the positions of joints free at this stage so that the pose can be arranged later.

The fine, white version of Milliput was used for these mannequin figures. Joints are still left free at this stage for repositioning later.

3. Sculpey can be applied to the Milliput before it is fully cured if need be, but it is best to wait a few hours. If you are in more of a rush the Milliput could be skipped altogether and Sculpey used for the thin halfway stage. Getting the Sculpey to stay on the metal will require a little more effort, but it can be done. This can then be hardened quickly using an oven or a heat gun (if the oven temperature does not exceed the recommended 130°C for Sculpey it should not affect the soldered joints). The advantages of this halfway stage are twofold. In the first place, it encourages some basic attention at least to the underlying anatomy of the figure. The wire armature was the skeleton; now simple muscles are being added. In the second place, soft Sculpey can be pushed around too much if left on its own. Each layer needs some firmer backing.

Working towards completion of modelling on one area. Some details are easier to achieve once the Sculpey has been hardened. It can be carved or shaved with the scalpel, as well as sanded or drilled.

4. The advantage of being able to harden portions or layers of Sculpey successively is that one can complete the modelling on one half of the figure, fix it and then work on the rest without fear of damage. The same can be done purely in Milliput without the need for heat, but this would involve longer periods of waiting. This kind of modelling is better achieved without too many breaks in concentration. One can gradually develop both a feeling for the material and a feeling for the shape and proportion while working, but the mood established can just as easily be broken. It is often better to make all the figures one requires at the same time.

The basis of effective figure modelling lies (as with everything else and even for figures at this scale) in observation of the real thing and the collection of clear references. When modelling figures we are both aided by, but also battling against, familiarity. We are so used to seeing human heads, for example, that we don’t properly look at them. One has to start by being fairly specific about what one wants, rather than hoping that the figure will somehow emerge in the process. Like many things, modelling a figure is ‘all in the preparation’ and there is nothing harder than trying to achieve a convincing result from a vague, imagined notion. A good understanding of anatomy is invaluable for a start, though perhaps not at that level of detail prescribed for larger-scale work. There are many good books devoted to figure modelling and some are listed in the Bibliography here. How one models – how one manipulates the clay into particular shapes – is very much a personal thing and can only be discovered through practice.

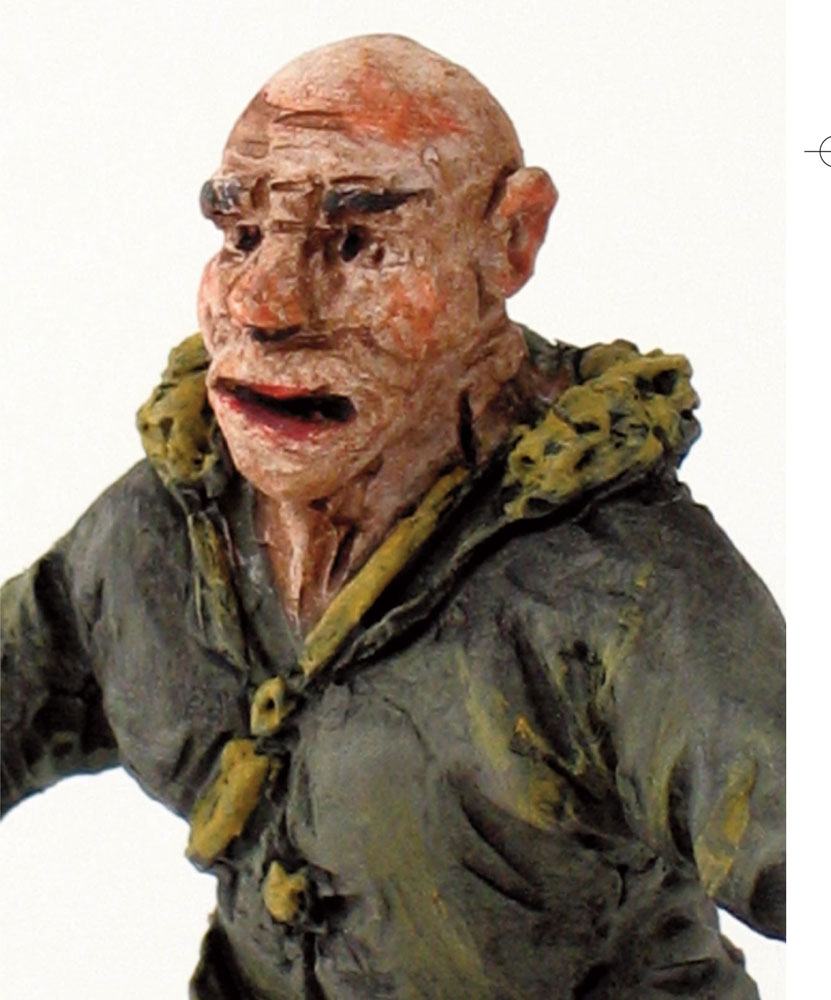

A group of almost completed figures. At this small 1:25 scale, it may be better (and it’s certainly easier!) to move towards caricature or simplification rather than attempting to be too realistic or elaborate.

Detail of one of the figures painted. At this scale, more is achieved by broader effects.

Example 2: modelling a tree

If one can achieve some confidence in modelling reasonably good figures, everything else is simple by comparison. One method of creating tree shapes was introduced in the previous chapter and that method could be used for the armature in place of the method here.

1. The armature in this case has been made by taking a number of equal lengths of florist’s wire, twisting them tightly together to form the trunk and dividing them up to form the branches. Proper florist’s wire is relatively soft and pliable because it has been annealed. The uncoated variety is recommended here and this is often sold in packs of a certain length. If this proves difficult to find, aluminium wire is the best option. This is even softer, but the Sculpey will provide enough rigidity when hard. In this model, fourteen strands have been twisted together. The advantage of this method, that of starting with a bunch and then dividing them, is that some of the work involved in starting with a thickness of trunk and thinning out branches occurs naturally. Note that some extra length is needed at the base if the tree is to be slotted into a baseboard.

The wire armature.

2. Sculpey can then be modelled onto the armature, with the twists of the wire helping it to stay in place. This can be done in one go, or built up in layers as described in the previous example.

The armature covered with Sculpey.

3. For the same reason that building in layers is recommended for the figure modelling, it is easier to harden the Sculpey at this stage and model a texture separately over it. The photo shows a section of trunk that has been partially clad with a bark formation. The thin layer of Sculpey is much easier to manipulate or impress without fear of distorting the general shape.