Section 7

Comprehension

- List 100. BDA Comprehension Strategies

- List 101. Context Clues and Word Meaning

- List 102. Syntax and Comprehension

- List 103. Comprehension Questions

- List 104. Question Starters for Discussions

- List 105. Proverbs

- List 106. Graphic Organizers

- List 107. Problem-Solving Guide

- List 108. Paragraph and Text Organization

- List 109. Character Traits

- List 110. Tone and Mood Words

- List 111. Point of View

- List 112. Language Registers

- List 113. Persuasive Techniques

- List 114. Literary Terms

Constructing meaning from print is a common definition of reading. A number of factors contribute to the process of comprehending or constructing meaning from text. Although word recognition and vocabulary knowledge are essential, research shows it is not sufficient (Almasi & Hart, 2005). Many students with adequate skill in these areas still have difficulty comprehending what they read. Duke and Martin's (2015, p. 253) review of research found ten processes contribute to comprehension: setting purposes, connecting prior knowledge, predicting, inferring, interpreting graphics and text features, evaluating content, monitoring comprehension, questioning, and summarizing. The National Reading Panel (2000) found strong scientific evidence to support these comprehension strategies: monitoring, cooperative learning, graphic organizers, text structure, question answering and question generating, and using multiple strategies flexibly.

Related to these strategies is the expectation that students develop skill recognizing and appreciating how a range of author's craft support or frame a reader's experience of a narrative text. Common Core State Standards (NGA & CCSSO, 2010) expect students to use point of view, language registers, tone and mood, characterization, and other elements to gain a deep and nuanced comprehension of a narrative text.

Knowing about these and other comprehension-related strategies is not enough. Students need to become strategic in their use; that is, they need to have these strategies in their repertoire of skills and have opportunities to select and apply them as needed to the texts and tasks they use for learning. In other words, students must become savvy and strategic readers. Laverick's (2002) idea of BDA strategies, or strategies that can be used before, during, and after reading to support comprehension, offers a useful plan.

Reading informational texts well requires some additional skills not generally used in narrative reading, including recognizing how authors use different types of paragraph or chapter organization depending on the content and determining the meaning of new vocabulary from the context clues provided by the author. Knowledge of persuasive techniques used also helps students recognize and evaluate argumentative and persuasive writing often encountered in informational texts.

The lists in this section address these instructional issues and support comprehension of narrative and informational texts. List 100, BDA Comprehension Strategies, for example, provides a walk-through of reader-selected strategies in service to comprehension in a framework that gives them both structure and flexibility. Other lists address questions and questioning, graphic organizers, author craft, paragraph organizations, and context clues. Still others address characterization, tone and mood, point of view, registers, and literary terms.

- Almasi, J., & Hart, S. (2015). Best practices in narrative text comprehension instruction. In L. B. Gambrell, & L. M. Morrow (Eds.), Best practices in literacy instruction (5th ed., pp. 223–248). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Dexter, D. D., & Hughes, C. A. (2011). Graphic organizers and students with learning disabilities: A meta-analysis. Learning Disability Quarterly, 34(1), 51–72. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/889930469?accountid=27354

- Duke, N., & Martin, N. (2015). Best practices in informational text comprehension instruction. In L. B. Gambrell & L. M. Morrow (Eds.), Best practices in literacy instruction (5th ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Laverick, C. (2002). B-D-A strategy: Reinventing the wheel can be a good thing. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 46(2), 144–147. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/40015436

- Moss, B., & Loh, V. S. (2010). 35 strategies for guiding readers through informational texts. New York: The Guilford Press. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/815957966?accountid=27354

- National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers (NGA & CCSSO). (2010). Common Core State Standards for English language arts and literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Washington, DC: Authors.

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00–4769. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (National Institute of Health Publication No. 00–4754). Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

- Williams, J. (2005). Instruction in reading comprehension for primary grade students: A focus on text structure. The Journal of Special Education 39(1), 6–18. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ693938.pdf

List 100. BDA Comprehension Strategies

List 100. BDA Comprehension Strategies

Students' success in understanding what they read depends on many factors, including the active reading and learning strategies they use before, during, and after (BDA) reading. These strategies scaffold student skills in predicting, questioning, monitoring, clarifying, associating, reacting, and responding while reading. During guided reading lessons, introduce and have students practice these strategies until they build competency and can independently apply them to new texts. Help students recognize which strategies work best with narratives or informational texts.

Not all strategies work equally well for all texts or for all students. It is important, however, that each student develops a repertoire of strategies to use before, during, and after reading to support their comprehension and learning. Before strategies will focus on preparation for reading, during strategies focus on keeping track of the content and dealing with new information, and after strategies tie it all together and enable the reader to respond to the story or information read.

Before-Reading Strategies

- Organize

- Gather everything you need: text, paper, highlighter, pen, sticky notes, dictionary, and assignment pad.

- Set aside enough time to complete the assignment or a particular part of the assignment.

- Set the purpose for reading: check your assignment. Most reading assignments have two parts: read and remember the main idea and details for discussion; read and remember content for a quiz; read and use the information; read and take notes; read and write a reaction; or read and answer questions. Your speed and style of reading will depend on your purpose.

- Tune in to the task

- Look at the title and headings: in a story they engage your interest; in a textbook they give the main idea or category of information of the section.

- Think about what you already know about the subject or the story.

- Think about the special directions you were given about the assignment.

- Think about what you will need to notice or remember in order to do the postreading assignment (details, main ideas, story line, character traits, point of view, setting, comparison to another story, figurative language, procedure, new terms, etc.).

- Check to see how the author organized her or his writing (chapters? headings? dialogue? numbered steps? vocabulary in bold, italics, or sidebar? texts + drawings or pictures?).

- Think about what you expect to find out by reading and why.

- Set up for success

- Make a KWL chart and fill in the columns for K and W.

- List group label: write all the words and concepts you know that are related to the topic; add the words from one or two peers and then sort them into groups; label the groups of words and review and discuss words in each labeled group as a foundation for new knowledge.

- Complete the anticipation guide provided by the author or teacher.

- Read the questions at the end so you'll recognize the answers when you get to them.

- Create your own questions based on the topic and headings.

- Pick a graphic organizer template that matches your task and set it up for the assignment.

- Set up your notebook Cornell notes style.

- Review the new vocabulary words and their definitions before reading.

- Start a word web or new word list for the reading.

- Compare your KWL or questions with a partner's.

- Plan a jigsaw with a partner: divide the questions or topics you will be responsible for.

During-Reading Strategies

- Find and mark

- Use a sticky note to mark the paragraph in which you found an answer to one of your questions or to your part of a jigsaw.

- Add important words to your word web.

- Write out the sentence in which a new word was found.

-

Write down the page number where you found important information (e.g., p.372).

If the book is yours:- Highlight an answer or important information when you see it.

- Put a check mark in the margin next to important information.

- Underline key new words.

- Highlight the key ideas needed for your part of a jigsaw.

- Keep track of progress

- “Talk” to the author. (Imagine saying “OK, I got that, I like this part, I wouldn't do it that way,” or whatever else you might say if the author were there with you as you read.)

- When you notice that you're telling the author that it doesn't make sense, go back to a part that did and reread. You may have missed an important clue. Then reread the part that didn't make sense. Follow the reading guide from the teacher as you read.

- Fill in a story map, a problem solution, or other graphic organizer as you read.

- Add a sticky note where you really liked what you read.

- Add a sticky note where the reading was difficult for you.

After-Reading Strategies

- Review the reading

- Check back on all marked sections.

- Add to your word web.

- Retell a short version of the story or text in your own words.

- Reread any parts that you marked because they were difficult.

- Think about your feelings for the story or text. (Was it interesting? Did you like it? Was it easy to follow? Did it help you learn?)

- Use what you've read

- Use the marked pages or sections to answer questions.

- Answer questions citing sections of the text where you learned the answers.

- Fill in the KWL chart.

- Write your reaction to the story or text.

- Create an outline or notes from the important information and key words.

- Complete your new vocabulary or spelling list.

- Write follow-up questions to research later on the same topic.

- Think about how this story or information is like what you have read before.

- Teach part of what you learned to a classmate.

- Finish the jigsaw with your partner(s).

- Summarize or write a précis of the reading.

- Complete a semantic feature analysis for the terms in the selection.

- Create mnemonics for key ideas that you want to recall.

- Rate the reading material's difficulty: too easy, just right, or too difficult.

- Rate the reading material's interest: very interesting, OK, or not very interesting.

- Rate the amount you learned: learned a lot, learned some, or learned very little.

List 101. Context Clues and Word Meaning

List 101. Context Clues and Word Meaning

Authors of both narrative and expository text provide information to their readers about the meaning of words that are important to understanding. In informational text, authors intentionally introduce new vocabulary through context clues to help readers understand the new concept in relation to what is already known. Authors may use several of these techniques in a unit to introduce and reinforce target words in print and online media. These techniques for building information on students' prior knowledge base are also effective in oral presentations. The Common Core State Standards expect students beginning in grade 2 to be able to determine the meaning of words and phrases in informational text.

To help your students acquire this skill, preview a text your students will read and note the types of context clues used by the author. Then, teach your students about those specific types of context clues and have them locate examples in their text. With partners, have students use the context clues to determine the meaning of the new words. Use these techniques in your presentations, worksheets, and other instructional materials. Having students write context clue sentences for new vocabulary words is also an effective strategy. The student-developed clue sentence can be included in their word logs and provide a reminder of meaning for target words.

The following examples demonstrate ten techniques for providing context clues to word meanings for a hypothetical text on minerals. A list of sentences for practice follows the examples.

- Direct statement/definition. Quartz is a mineral.

- Classifications. Quartz, a mineral, is composed of one part silicon and two parts oxygen.

- Examples. Minerals such as diamonds and sapphires are rare and expensive.

- Appositive. Minerals are inorganic, nonliving substances found in the earth.

- Synonym. A mineral's luster or shininess helps identify it.

- Function indicator. The geologist used micrometer calipers to measure the length and width of the tiny mineral crystals.

- Compare and contrast. Coal, unlike minerals, is an organic substance formed from decayed animal and plant life.

- Analogy. Quartz is to inorganic as coal is to ___________; quartz:inorganic:: coal:__________.

- Experience. The sheet of mica was almost transparent enough to see through completely.

- Morphology. Quartz is an igneous rock. The word igneous has the same base as the word ignite. They both come from the Latin word ignis, meaning fire. The silica and oxygen that make up quartz are found in middle layers of earth where it is so hot they are in a melted state. When some of it gets closer to the surface and cools, crystals of quartz are formed.

Use this list for student practice determining the meaning of the italicized words from context clues.

- Ferns, flowerless plants, come in many varieties.

- A centimeter is a small unit of measurement about one-half of an inch in length.

- Chlorophyll, a green substance in plants, enables them to turn light from the sun into energy.

- Maps use a key, or legend, to explain the meaning of each of the symbols used in the map.

- The astronomer, a scientist that observes the sky, was using his telescope to look at the stars.

- Thunder, unlike lightning, cannot be seen.

- Arctic is to cold as tropical is to ___.

- The texture of the animal's fur was so soft it felt like velvet.

- Powhatan is to chief as Obama is to president.

- An atlas, a book of maps, can be useful when driving.

- The prime meridian divides the earth into the eastern and western hemispheres.

- A rectangle, a closed shape, has four sides.

- As we got closer to the lake, we began to step on squishy land called a marsh.

- The scientist uses a microscope to look at the tiny cells of a plant.

- A curve, an open figure, reminds me of rainbows.

- An iceberg is a large mass of ice that came apart from a glacier and floated out to sea.

- Lines of longitude, not latitude, run from north to south but measure east and west.

- Oral history, not textbooks, enables you to hear people talking about past events they experienced.

- Consumers, people who buy goods and services, purchase them for their own or their family's use.

- Emma wanted a bike she saw at a yard sale, but she had no money! She bartered with the owners and walked their dog every day for a week in exchange for the bike.

- The postal service collects and delivers mail all across the country.

List 102. Syntax and Comprehension

List 102. Syntax and Comprehension

Knowledge of syntax and the workings of our language is a powerful comprehension tool. But not all students recognize just how useful this is in a learning situation. Use this story and list of questions to demonstrate the impact on comprehension of word order in sentences; noun, adjective, and adverb markers; verb forms; plural spellings; and punctuation. These syntactical features of language help us see connections and make associations even when we have limited knowledge of a new subject. It is important also for students to recognize the need to ask for help if they encounter passages in texts that seem to have many unfamiliar words.

For a long time, Haro, the nimp fizbin, was the only fizbin in the zot. Every midsee, he would cond and ren, cond and ren, cond and ren. Then one midsee, Haro was zommed! There, in the middle of the parmon, was the nimpest fizbin and she was conding and renning just like Haro. Haro was so arky! He dagged up to the nimpest fizbin and chared. Soon Haro and the nimpest fizbin, Bindy, were ponted. Then every midsee, they conded and renned abatly in the parmon of the zot.

- Who was Haro?

- What did he do every midsee?

- How do you think Haro felt in the beginning of the story? Why?

- What words helped show his feelings?

- Where was Bindy when Haro first saw her?

- What was she doing?

- How did Haro act when he saw her?

- How do you think Haro felt at the end of the story? What changed his feelings?

- How are Haro and Bindy the same?

- How are they different?

- List four things that a fizbin can do.

- Which is larger, the zoyt or the parmon?

- Add a new sentence to tell what happened later.

- Rewrite the story, and substitute real words for these:

fizbin zommed midsee arky cond abatly ren zot

List 103. Comprehension Questions

List 103. Comprehension Questions

Questions help focus student thinking and enable teachers to assess whether students are moving toward success in a particular learning goal or reading standard. For a long time, teachers asked questions dealing with mostly lower-order thinking skills—those that required students to simply recall facts and details. Teachers now focus on higher-order thinking (also referred to as HOTS) in nearly all lessons, including instruction in subjects other than language arts.

This list provides examples of question types that address key cognitive skills required by the Common Core and other rigorous language art standards. They are based on the story of Cinderella but can be adapted for any text.

Vocabulary

- Question to help students understand the precise meaning of a particular word. For example: What does the word jealous mean? What did the stepsisters do that showed they were jealous?

- Question to help students understand multiple meanings of words. For example: What does ball mean in this story? It says: “At last the day came and the sisters, dressed in their finery, went to court.” What does court mean in this story?

- Question to help students understand figurative language. For example: What does it mean when it says: Soon after she married Cinderella's father, the step-mother showed her true colors?

- Question to help students understand technical language. For example: What part of a house is the garret?

- Question to help students understand words used in the text in terms of their own lives. For example: Have you ever known someone who was jealous? Have you ever been jealous? Why?

Determining central theme

- Question to help students focus on main idea or theme: For example: What is the story of Cinderella mainly about? What other title(s) could be used for this story?

Point of view

- Question to help students recognize point of view. For example: Who is telling the story, a narrator or one of the characters? How can you tell?

Citing evidence

- Question to help students draw on evidence to support their conclusions. For example: What evidence did you find in the story that Cinderella was treated badly by her stepmother and stepsisters?

Word choice

- Question to help students see how words contribute to meaning or tone. For example: What are some of the words and phrases the author uses to create the feeling that the prince was falling in love with Cinderella at the ball?

Pronoun referents

- Question to help students understand what or who some pronouns refer to and how to figure them out. For example: In the second sentence of the third paragraph, who does she refer to? How do you know?

Use of illustration

- Question how the illustrations help the reader understand new words in a story. For example: In the story it says the fairy godmother changed six mice into the finest horses and six lizards into the finest footmen. Can you use the illustration to figure out what a footman is? What is it?

Causal relations: direct and inferred

- Question to help students recognize causal relations stated directly in the text. For example: Why were Cinderella's stepsisters jealous of Cinderella?

- Question to help students infer causal relations not directly stated in the text. For example: Why did the stepmother give Cinderella extra work to do on the day of the ball?

Sequence

- Question to help students understand that the sequence of some things is unchangeable. For example: What steps did the Fairy Godmother follow in order to make a coach for Cinderella? Could the order of these steps be changed? Why or why not?

- Question to help students understand that the sequence of some things is changeable. For example: What chores did Cinderella do on the day of the ball? Could she have done some of them in a different order? Why or why not?

Comparison

- Question to encourage students to compare things within the text. For example: How did the behavior of the stepsisters differ from the behavior of Cinderella?

- Question to encourage students to compare elements of the story with elements of other stories. For example: In what ways are the stories of Cinderella and Snow White similar? In what ways are they different?

- Question to encourage students to compare elements of the story with their own experiences. For example: If you were in Cinderella's place, how would you have acted toward your stepsisters? Is this similar or different from the way Cinderella acted?

Inference

- Question to help students use their prior knowledge and schemata to make inferences. For example: What were Cinderella's feelings when the clock struck twelve and she had to leave the ball?

Generalizing

- Question to encourage students to generalize from one story to another. For example: Are most heroines of fairy tales as kind as Cinderella? Give some examples to support your answer.

- Question to encourage students to generalize from what they read to their own experiences. For example: Can we say that most stepmothers are mean to their stepchildren? Why or why not?

Predicting outcomes

- Question to encourage students to think ahead to what may happen in the future and make a prediction. For example: After Cinderella's beautiful dress changes back to rags, what do you think happens?

Summarizing

- Question to help students summarize or restate the important points in their own words. For example: Retell a short version of the story with just the most important parts.

List 104. Question Starters for Discussions

List 104. Question Starters for Discussions

Discussion has been found to be one of the most effective techniques for improving comprehension. Discussion questions help students focus attention on key information in the text, see connections, listen to others' interpretations of text, and put fleeting thoughts into words. Discussion also is an opportunity for students to get feedback from the teacher and from peers. Many teachers try to frame questions in a way to ensure they lead to higher-order thinking. One way to do this is to use verbs associated with Bloom's revised taxonomy.

Teachers find it very helpful to prepare questions for discussion in advance. Here are some question starters that will guide your high-order thinking questions.

Remember

- Use at least three adjectives to describe ______.

- What happened after ____.

- Describe the setting of the story _____.

Understand

- What is the main idea of the story?

- What is the moral of the story?

- How would you read the parts of the story where the stepsisters are talking? Why?

Apply

- If this story took place in 2020, what would be different?

- What other outcomes to the story can you think of?

- If you could interview the main character, what questions would you ask?

Analyze

- Rank these characters on the spectrum from good to evil.

- What factors lead to this outcome?

- Why did the process fail?

Evaluate

- What are the pros and cons of the proposed policy for the employees and for the owner of the company?

- How would you determine which was a better choice?

- What data would you need to make an informed decision about this?

Create

- Imagine a ____ of the future. What new features would it have and why?

- What new uses can you think of for _______?

- Propose a law that addresses the problem we are discussing.

List 105. Proverbs

List 105. Proverbs

Proverbs are common, wise, or thoughtful sayings that are short and often applicable to different situations. What we think of as American proverbs are really an amalgam of sayings brought from every corner of the world and handed down in families and neighborhoods, from the ancient Chinese A picture is worth a thousand words to the colonial American A stitch in time saves nine. Speakers of other languages often report a version of a proverb in their home languages. (See List 184, Dichos—Spanish Proverbs, for proverbs that have their roots in Spanish.) You'll find some proverbs seem to contradict others, as in Haste makes waste and He who hesitates is lost. One or the other is surely good advice, depending on the circumstance!

Proverbs make excellent prompts for writing assignments or to launch a good discussion about a moral or perspective. Proverbs can also spur some creative writing, but don't be surprised if the result is humorous. For example, one teacher gave the first part of a proverb and asked students to tell the ending. The teacher reported that her first grader completed A penny saved is …with not much! You and your students might enjoy adding to this collection.

Relationships

- A false friend and a shadow stay only while the sun shines.

- A false friend is worse than an open enemy.

- A friend in need is a friend indeed.

- Absence makes the heart grow fonder.

- All's fair in love and war.

- A friend who shares is a friend who cares.

- A good neighbor, a found treasure!

- A man is judged by the company he keeps.

- A merry companion is music on a journey.

- Better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all.

- Blood is thicker than water.

- Familiarity breeds contempt.

- Good fences make good neighbors.

- If you can't beat them, join them.

- Like father, like son.

- Love will find a way.

- Marry in haste, repent at leisure.

- Misery loves company.

- Short visits make long friends.

Action and determination

- A faint heart never won a fair lady.

- A good deed is never wasted.

- A little too late is much too late.

- A quitter never wins and a winner never quits.

- A rolling stone gathers no moss.

- A stitch in time saves nine.

- Actions speak louder than words.

- All things come to those who wait.

- Don't put off for tomorrow what you can do today.

- He or she who hesitates is lost.

- He or she who sits on the fence is easily blown off.

- If you can't stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.

- If you want something done, ask a busy person.

- Leave no stone unturned.

- Lost time is never found.

- Make hay while the sun shines.

- Never put off ‘til tomorrow what you can do today.

- No pain, no gain.

- Nothing ventured, nothing gained.

- Of all the sad words of tongue or pen, the saddest ones, “It might have been.”

- Sometimes you have to run just to stay in place.

- Strike while the iron is hot.

- When the going gets tough, the tough get going.

- Where there's a will, there's a way.

Caution

- Better safe than sorry.

- Don't cross the bridge until you come to it.

- Forewarned is forearmed.

- Haste makes waste.

- Learn to walk before you run.

- Look before you leap.

- Waste not, want not.

Encouragement

- Every cloud has a silver lining.

- Every path has a puddle.

- Every slip is not a fall.

- He who rides slowly gets just as far, only it takes longer.

- If at first you don't succeed, try, try again.

- If you come to the end of your rope—tie a knot in it and hang on.

- The darkest hour is just before the dawn.

- The first step is always the hardest.

Appearances

- Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

- Beauty is only skin deep.

- Clothes do not make the man.

- Every mother's child is handsome.

- Love is blind.

- The beard does not make the philosopher.

- The grass is always greener on the other side of the fence.

- You can't tell a book by its cover.

Good deeds

- Charity begins at home.

- Civility costs nothing.

- Do right and fear no one.

- Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

- Give credit where credit is due.

- Great oaks from little acorns grow.

- One good turn deserves another.

- To err is human; to forgive, divine.

- Two wrongs don't make a right.

Words

- A picture is worth a thousand words.

- A soft answer turneth away wrath.

- A tongue is worth little without a brain.

- A word of praise is equal to ointment on a sore.

- A word spoken is not an action done.

- Ask a silly question and you get a silly answer.

- Ask no question and hear no lies.

- Bad news travels fast.

- Brevity is the soul of wit.

- Sticks and stones may break my bones but names can never hurt me.

- Still waters run deep.

- The pen is mightier than the sword.

- The squeaky wheel gets the grease.

- There's many a slip between cup and lip.

Animals

- A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.

- A leopard cannot change its spots.

- Birds of a feather flock together.

- Curiosity killed the cat.

- Don't change horses in midstream.

- Don't count your chickens before they're hatched.

- It is better to have a hen tomorrow than an egg today.

- Let sleeping dogs lie.

- One camel doesn't make fun of another camel's hump.

- The early bird catches the worm.

- When the cat's away, the mice will play.

- You can lead a horse to water but you can't make it drink.

- You can't teach an old dog new tricks.

Money and wealth

- A fool and his money are soon parted.

- A penny saved is a penny earned.

- All that glitters is not gold.

- Better a dollar earned than ten inherited.

- Better to heaven in rags than to hell in embroidery.

- Don't put all your eggs in one basket.

- Early to bed, early to rise makes a man or woman healthy, wealthy, and wise.

- Fortune and misfortune are next-door neighbors.

- He or she who pays the piper calls the tune.

- It takes pennies to make dollars.

- Lend your money and lose your friend.

- Money burns a hole in your pocket.

- The second million is always easier than the first.

- They who dance must pay the fiddler.

- Time is money.

- You reap what you sow.

Food

- A tree is known by its fruit, not by its leaves.

- An apple a day keeps the doctor away.

- Don't cry over spilt milk.

- Don't bite the hand that feeds you.

- Don't count your chickens before they're hatched.

- Every pea helps to fill the pod.

- God gives food but does not cook it.

- Half a loaf is better than none.

- He or she who would eat the fruit must climb the tree.

- Honey catches more flies than vinegar.

- The apple never falls far from the tree.

- The proof of the pudding is in the eating.

- There's no such thing as a free lunch.

- Too many cooks spoil the broth.

- Too many square meals make too many round people.

- You can't have your cake and eat it too.

Miscellaneous

- A bad broom leaves a dirty room.

- A chain is as strong as its weakest link.

- A clean conscience makes a soft pillow.

- A good beginning makes a good ending.

- A house divided cannot stand.

- A hovel on the rock is better than a palace on the sand.

- A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.

- A man is not better than his conversation.

- A person who gets all wrapped up in himself makes a mighty small package.

- A rising tide lifts all boats.

- A watched pot never boils.

- Adversity makes strange bedfellows.

- All good things come to an end.

- An idle brain is the devil's workshop.

- Beggars can't be choosers.

- Better late than never.

- Better safe than sorry.

- Charity begins at home.

- Confession is good for the soul.

- Different strokes for different folks.

- Do as I say, not as I do.

- Don't judge a man until you've walked in his boots.

- Don't put the cart before the horse.

- Everybody's business is nobody's business.

- Fact is stranger than fiction.

- Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me.

- Good things come in small packages.

- He who holds the ladder is as bad as the thief.

- He or she gives twice who gives quickly.

- He or she who lives by the sword, dies by the sword.

- Hindsight is better than foresight.

- If you're not part of the solution, you're part of the problem.

- In unity there is strength.

- It is better to bend than break.

- It is nice to be important, but it is more important to be nice.

- It never rains but it pours.

- Living in worry invites death in a hurry.

- Make the house clean enough to be healthy and dirty enough to be happy.

- Necessity is the mother of invention.

- No news is good news.

- Obstinacy is the strength of the weak.

- Old habits die hard.

- One can learn even from an enemy.

- One good turn deserves another.

- People who live in glass houses shouldn't throw stones.

- Pleasant hours fly fast.

- The best things in life are free.

- The road to hell is paved with good intentions.

- The stable wears out a horse more than a road.

- Variety is the spice of life.

- You're never too old to learn.

List 106. Graphic Organizers

List 106. Graphic Organizers

The term graphic organizer refers to a visual display that organizes and shows the relationships among facts, concepts, ideas, or other types of information. Graphic organizers (GOs) have been used for a long time to support student learning. One of the most common, the Venn diagram, has been in use since 1881. The following lists outline the benefits of using graphic organizers, enumerate attributes of effective graphic organizers, and provide some tips for using graphic organizers. These lists are followed by an exemplar list of commonly used graphic organizers.

Graphic organizers can help your students by doing the following:

- Organizing complex information in simple arrays

- Showing relationships or associations among entities

- Showing characteristics or attributes for more than one thing

- Focusing attention on key elements in text

- Guiding thinking as the organizer is completed

- Enabling students to see ideas and relationships while thinking

- Involving more than one modality in the process of learning and understanding

- Painting a big picture of the problem or field

- Clarifying information by considering relationships (Main idea–detail, order, sequence, part-whole, associated attributes, etc.)

- Communicating complex information or processes simply

- Highlighting types of data that are missing or incomplete

- Supporting students as they work through complex processes (experiments, story grammars, developing arguments, problem solving, decision making, comparing and contrasting multiple concepts, evaluating outcomes, etc.)

- Organizing information for presentation orally or in written form

Effective Graphic Organizers

- Use simple and uncluttered design

- Are chosen specifically for the type of information and relationships

- Portray information clearly and unambiguously

- Use visual features (color, fonts, scale, etc.) to support organization and information

- Reflect the level of sophistication of students and topics

Tips for Teaching with GOs

- Identify types for specific purposes (comparison, traits, sequence, story, grammar) and use consistently.

- Model how to use each type of GO as you introduce it.

- Assign pairs or small groups to work on a GO together.

- Integrate into teaching—select and use specific types before, during, and after reading.

- Use consistent and grade-appropriate labels for parts.

Types of Graphic Organizers

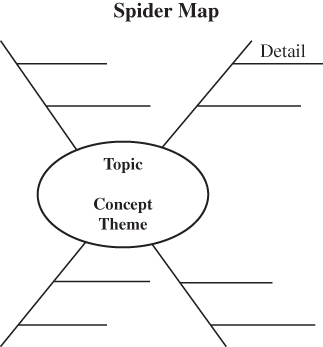

| Spider Map | |||||||||||||

|

Spider maps are often used to show key ideas and details. For example, it could be used to describe a place (geographic region), a process (meiosis), a concept (altruism), or a proposition (children should be vaccinated). Some questions to use:

|

||||||||||||

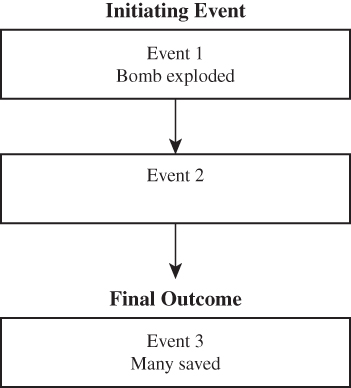

| Flow Chart or Chain of Events Flow charts or chain of events are used to describe and show the stages of something (the life cycle of a butterfly), the steps in a procedure (how a bill becomes a law), a sequence of events (how the invention of the movable type printing press led to the Renaissance), or the chronology of major events in in the life of a person, institution, or political entity. Key questions to use:

|

|

||||||||||||

|

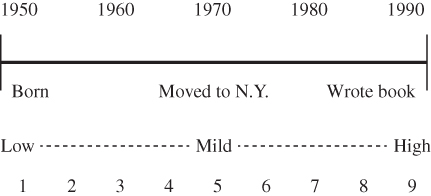

Time Line or Continuum A time line is used to show chronological or time order. It uses a variety of time scales from nanoseconds to millennia or even light years. Its related continuum graph shows amounts, degrees, or ratings (few to many, least to most, 1 to 5, preschool to college, etc.). Units or scales are important for conveying information accurately. |

||||||||||||

| Compare-and-Contrast Matrix |

|

||||||||||||

| A compare-and-contrast matrix uses a table to array the attributes of two or more things. Typically the attributes are listed down the first column and the items being compared are listed in the first row. Question to use:

|

|||||||||||||

|

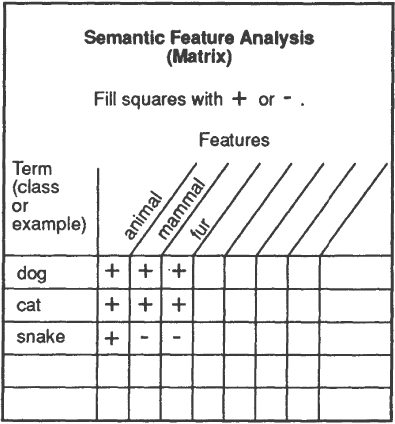

Semantic Feature Analysis Matrix A semantic feature analysis matrix is used to show the presence or absence of a list of traits or attributes for a number of samples. In the example at left, the first column shows different samples of pets, and the potential features for pets are arrayed across the top of the grid. These matrices are often used in science and social studies content. A plus sign (+) indicates that the sample has the attribute or feature and a minus sign (-) indicates the sample does not have the feature or attribute. |

||||||||||||

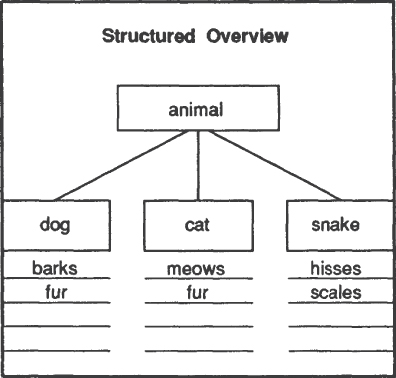

| Structured Overview A structured overview organizes information about components of a larger unit. For example, many social studies texts use a structured overview to show the powers of the three branches of the US federal government. When provided to students before a reading assignment, structured overviews guide students' attention and note taking and make it easy to keep information linked to the appropriate component. Scaffold students by filling in the main category and subcategories. |

|

||||||||||||

|

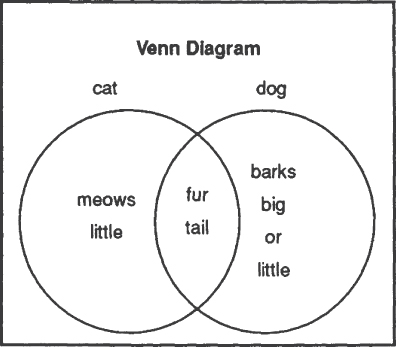

Venn Diagram Venn diagrams are used to compare and contrast two or more things by showing the traits they have in common and the traits they have uniquely. Venn diagrams are used frequently in math, set theory, logic, social sciences, science, and philosophy. |

||||||||||||

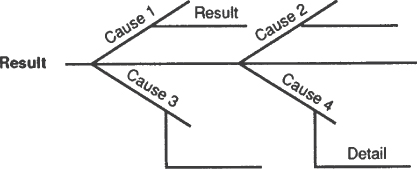

| Fishbone or Cause-and-Effect Diagram Fishbone diagrams are used to show actions or circumstances that contribute to a result. Once major causes are listed, each can be explored more deeply so a greater understanding can be achieved. To use a fishbone diagram in planning, begin with the end result and then work back through the major steps and the details of those steps. |

|

||||||||||||

|

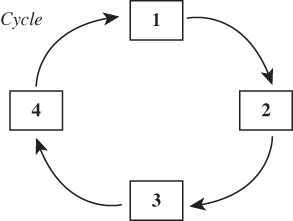

Cycle Diagram Cycle diagrams are used to depict a repetitive set of steps in which the last step leads again to the first step in an unending sequence. Many concepts in the natural sciences can be represented using cycle diagrams including the water cycle and life cycle. It is customary to represent the major stages of a cycle in a clockwise sequence. |

||||||||||||

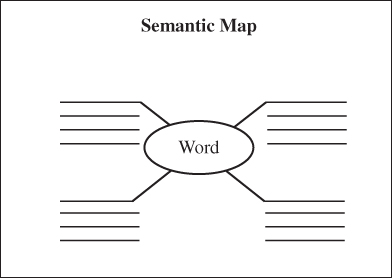

| Semantic Map A semantic map is often used to help students learn and remember the meaning of key vocabulary words. The target word is placed in the center of the map and groups of related words and phrases are connected to it. For example, if the target word is in the center, a list of synonyms is placed in the upper right corner, a list of antonyms is placed in the upper left corner, the dictionary definition is placed in the lower left corner, and a sentence using the target word is placed in the lower right corner. |

|

||||||||||||

|

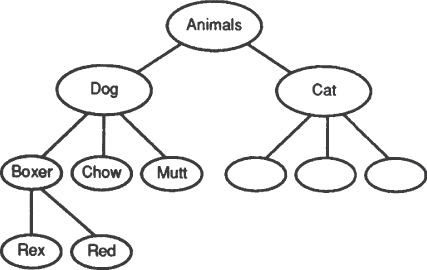

Network Diagram Network diagrams help visualize how different parts of a system are related to one another and how information or effect is passed up, down, or even across elements in the system. They also help solve problems by locating where on a path a link is missing or aligned incorrectly. A related graphic organizer is the tree diagram, which is used to show family relationships and other hierarchical situations. Tree diagrams, usually arrayed horizontally, are also used to show all possible outcomes of experiments in probability. |

||||||||||||

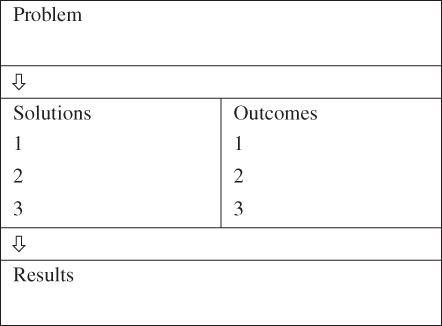

| Problem-Solution Diagram The problem-solution diagram is used to identify the problem or conflict in a story, list the possible or attempted solutions and their outcomes, and discuss the final results or resolution to the problem. It is also used to track the outcomes of various experimental efforts to solve a problem. |

|

List 107. Problem-Solving Guide

List 107. Problem-Solving Guide

John Dewey said, A problem well put is half-solved. Indeed, stating the problem in your own words is one of the most often suggested first steps. Using combinations from this three-step guide will help students solve most problems. Remember, if you immediately know the answer to a question, it wasn't a problem. Problems require creativity and perseverance.

- Understand the problem.

- State the problem in your own words.

- Visualize the problem.

- Act out the problem.

- Draw a diagram, flowchart, or picture of the problem.

- Make a table, Venn diagram, or graph of the problem.

- Look for patterns in the problem.

- Compare it with another problem you have solved.

- List everything you know about it.

- Think about its parts, one at a time.

- Propose and try solutions.

- Use logical reasoning.

- Brainstorm alternatives.

- Write an equation.

- Choose an operation and work it through.

- Estimate and check the results.

- Work backward from the product or result.

- Link a solution to each part of the problem.

- Solve problems within the problem.

- Evaluate and sort the information you have.

- Organize the information in a grid or matrix.

- Eliminate solutions that don't work.

- Solve a simpler version of the problem first.

- Check the results.

- Fill in an information matrix.

- Redo the computation with a calculator.

- Create a flowchart or visual of the answer.

- Dramatize the result.

- Compare the results with the estimates made earlier.

- Use the results on a trial basis.

- Monitor the effects of the results over time.

- Check the answer with a reference source.

- Have another team or the teacher critique the result.

List 108. Paragraph and Text Organization

List 108. Paragraph and Text Organization

Fiction has a simple literary structure. A story has characters, a setting, and a plot or sequence of events in which a problem is solved. Stories have a beginning where all the parts are introduced, a middle where tension builds, and an ending during which the problems are resolved. Children listening to stories read aloud are able to pick out these elements with just a little help.

Text organization or structure in nonfiction is more complex. Text organization refers to the way information is arranged and depends on the type of information the author is presenting. As students read informational texts they need to know and be able to recognize the common patterns authors use to organize and present ideas. And, as students write they need to understand which organizational patterns will best support their communication goals. These expectations are included in the Common Core State Standards for both reading and writing beginning in grade 4. In primary grades, students focus on more visual organizational helpers, such as headings, sidebars, and illustrations.

Knowing how information is organized enables the reader to keep track of ideas, see relationships among them, anticipate what will come next, and make sense of the ideas as they are read. In other words, understanding text structure helps students construct meaning from print.

An author may use more than one text structure in a chapter, depending on what the material is about. For example, a chapter in a history text may begin with a description, then a chronology of the development of the location, and end with a comparison of this location with another. Authors use signal words to help readers recognize the organization and direct their attention appropriately. (See List 144, Signal and Transition Words.) This list includes the most frequently used organizational structures students will encounter.

- Description. Some nonfiction text are written to describe something or someone. In a descriptive structure, the author provides the focal point—the person, event, idea, or thing of interest—and lists its characteristics and features using sensory details to paint a picture in the mind of the reader. The author includes facts that tell what it is, what it does, what it looks like. Many authors include a definition, synonyms and antonyms, and examples including those framed as similes, metaphors, or analogies to help the reader understand.

Some signals for description include for example, such as, characteristics, features, is described as, like, similar to, for instance, to illustrate, and sense words.

- Chronological order. The word chronological means “time order” and information presented in chronological order is organized by when things happened. The when may be expressed as years, dates, days of the week, or even hours. The important aspect is that the order matches the order in which the events occurred. Occasionally, an author will present things in reverse chronological order, for example, starting with this year and moving back in time. Topics in history or in the development of something over time are usually presented in chronological order.

Some signals for chronological order include years, dates, days of the week, historic periods, and words such as first, second, then, next, before, finally, after, during, and until.

- Sequential order. Sequential order is similar to, but not the same as, chronological order. The important difference is that sequential order shows the order of steps to a process but does not tie them to a specific time or date. For example, directions for making muffins are in sequential order and it doesn't matter whether you bake them on Thursday, in February, or in 2019. The sequence is the important thing. In addition being used for directions, sequential order can be used for most processes, including how caterpillars become butterflies, bills become law, or teams qualify for playoffs.

Some signals for sequential order include first, next, before, last, and then.

- Compare and contrast. When the author wants to explore the ways two or more things are the same and different, the compare-and-contrast structure is used. This is a useful pattern if the reader knows about one thing and is learning about the other. Using compare and contrast in a sense would be like using synonyms and antonyms or analogies like this one. It is important for students to learn that difference does not imply that one thing is better than another. A blue pen is not better or worse than a green one.

Usually an author will tell the ways two things are the same and then tell how they differ. If only similarities are discussed, it is called a comparison; if only differences are discussed it is called a contrast. Authors may also use a table with the features of the two things being compared side-by-side or a Venn diagram as a text support for comparisons and contrasts.

Some signals for compare and contrast include like, such as, unlike, both, also, neither, different, similarly, and on the other hand.

- Cause and effect. Authors of informational texts often describe events (effects) and tell why (causes) they happened. The cause-effect relationship can be tricky for students because of its inherent chronological aspect: causes occur before their effects but not everything that happens before contributes to the outcome, results, or effect. Another aspect of cause and effect that can be problematic is that there is not always a one-to-one correspondence. Things happen as a result of multiple contributing factors. Cause-and-effect text can be written describing the cause first and then the effect or describing an event and then telling how it came to be. The cause-and-effect organization is often found in history, economics, and science texts.

Some signals for cause and effect include cause, effect, reason, outcome, result, happened, contributing factor, factors, explained by, lead to, because, since, affected, and due to.

- Problem and solution. When authors use the problem-and-solution structure they introduce and describe a problem or negative situation and then present one or more solutions that the author argues can, should, or may be used to address the problem. In describing the problem, facts and unmet needs are often included. These form criteria for judging the merit of the solution or solutions posed. The problem and solution structure is often found in texts about social studies, politics, science, and engineering topics.

Some signals for the problem-and-solution structure include situation, problem, issue, solution, remedy, idea, proposal, resolution, cost, benefits, one thought, and result.

- Order of importance. Some topics are best discussed according to the order of importance or hierarchy to which they belong. A hierarchy, such as a government or company, is a system or arrangement of levels with one level being above or superior to another and other levels being below or inferior. In a company, for example, the president or owner is at the top level, with managers on the level below, followed by workers on the next level down. When using this structure, the author may begin at the bottom level of the organization and work up or begin at the top and work down. An organization chart or tree diagram is often used to support this type of text. Order of importance structures are often used in business, civics, economics, and natural sciences.

Some signals of an order of importance structure are hierarchy, organization, level, category, subcategory, class, ranking, command, executive, managerial, branch, families, and species.

- Advantage and disadvantage. An author will use the advantage-disadvantage structure to evaluate one thing against a set of criteria. The author generally begins with a description of a need including attributes or criteria desired to fill the need. Then the author introduces a proposed answer or solution to the need and considers it relative to the criteria with the matches counted as advantages and the nonmatches counted as disadvantages. This differs from problem solution in that advantage-disadvantage usually has a neutral perspective whereas a problem solution is more argumentative or persuasive in its presentation.

Some signals of advantage-disadvantage include advantage, disadvantage, plus, negative, and on the other hand.

- Spatial organization. Authors use spatial organization when the location of one element in relation to another element is important. Spatial organization is often used to orient a visitor to a space, to describe natural phenomena where they are found, or to give detailed descriptions. For example, text describing the geology of the earth will often use spatial organization and begin the description with the earth's outermost crust, then proceed inward to the mantle, then outer core, and finally the inner core.

Some signals of spatial organization include above, below, on top, at the bottom, to the north, beneath, next to, across from, behind, and near.

- List. A simple and often used text structure is the list. Authors use the list to organize numerous items in a category to make the information more accessible. Lists are often alphabetized or numbered to speed location of a particular item on the list or lists may group items into categories and subcategories. Directories, menus, Q&A, FAQs, fact sheets, and dashboards are some common examples of the list organization.

List 109. Character Traits

List 109. Character Traits

Even before students learn to read independently, we talk with them about the characters they meet in a wide range of stories. We probe why a character acted in a certain way. We ask students to predict behavior based on what they know about a character. These forward inferences may combine text-based or reader-based knowledge. We also ask students to use evidence from a character's actions in the story to describe the character's personality traits. These discussions begin early. By grade 3, students are expected to identify and describe a character's actions, thoughts, and motivations.

To support this goal, direct instruction on character traits is necessary. Begin with the definition: Character traits are the patterns of behavior and attitudes that make up someone's personality. They stay with the person and influence what they do, say, and think. Provide examples of traits and ask students what a person with x trait is likely to do in a specific circumstance. Next, brainstorm words that describe different traits or personalities. An effective Q&A strategy for young students is to ask questions such as, Would a messy person have a very neat closet? Would a greedy person offer to share his or her games? Would you expect a punctual or tardy student to be late?

Provide students with a graphic organizer to note the page number and specific words in a story that describe the character or show actions that suggest the character's traits. Older students can read on their own and keep a log of the evidence. Brainstormed lists of traits make excellent word walls that can also support character development in writing. Here is a list of character traits, personality traits, and behavior characteristics to get you started.

Primary

- absent-minded

- adventurous

- affectionate

- afraid

- alert

- amusing

- angry

- annoyed

- anxious

- attentive

- babyish

- bad

- bashful

- bored

- boyish

- brainy

- brave

- bright

- brilliant

- busy

- calm

- capable

- careful

- caring

- childish

- clever

- clumsy

- competitive

- confused

- considerate

- cooperative

- courageous

- crafty

- cross

- cruel

- curious

- cute

- dainty

- dependable

- dishonest

- disobedient

- disrespectful

- disruptive

- dreamy

- eager

- excited

- expert

- fair

- fearful

- fearless

- finicky

- flexible

- forgetful

- friendly

- frightened

- funny

- fussy

- generous

- gentle

- good

- grateful

- greedy

- grouchy

- grumpy

- guilty

- happy

- healthy

- helpful

- honest

- hopeful

- jealous

- jolly

- kind

- lazy

- leader

- liar

- loud

- lovable

- lucky

- messy

- naughty

- neat

- nice

- noisy

- obedient

- organized

- picky

- playful

- pleasant

- polite

- popular

- predictable

- punctual

- quick

- quiet

- quirky

- reasonable

- sad

- satisfied

- scholarly

- selfish

- serious

- sharing

- shy

- silly

- sloppy

- sly

- smart

- sneaky

- spoiled

- stern

- strict

- strong

- sweet

- talented

- thoughtful

- thoughtless

- tidy

- trustworthy

- truthful

- understanding

- unfriendly

- unhappy

- unkind

- unpredictable

- unreliable

- unselfish

- wicked

- wise

- wishful

- worried

Elementary

- able

- abrupt

- active

- adaptable

- admirable

- aggressive

- agreeable

- airy

- ambitious

- appreciative

- bizarre

- blue

- boastful

- bold

- businesslike

- carefree

- careless

- cautious

- challenging

- charming

- cheerful

- cold

- colorful

- competent

- complex

- conceited

- concerned

- confident

- confidential

- courteous

- cowardly

- crazy

- creative

- criminal

- crisp

- critical

- dangerous

- daring

- dark

- delicate

- demanding

- destructive

- difficult

- dignified

- diligent

- disagreeable

- discouraged

- distractible

- dull

- educated

- efficient

- embarrassed

- energetic

- evil

- excitable

- exciting

- experimental

- extraordinary

- extreme

- faithful

- false

- fighter

- firm

- focused

- foolish

- forgiving

- fresh

- genuine

- giving

- gloomy

- glum

- graceful

- grand

- heroic

- high-spirited

- humorous

- hurried

- imaginative

- immaculate

- immature

- impatient

- impolite

- inconsiderate

- independent

- industrious

- informed

- innovative

- inventive

- jovial

- kindly

- knowledgeable

- light

- lively

- lonely

- loving

- loyal

- mature

- mischievous

- moody

- mysterious

- nagging

- nervous

- observant

- odd

- orderly

- ordinary

- patient

- peaceful

- perfectionist

- persistent

- persuasive

- pleasing

- positive

- practical

- private

- proud

- relaxed

- responsible

- ridiculous

- romantic

- rough

- rowdy

- rude

- self-confident

- simple

- sincere

- skillful

- smooth

- soft

- spunky

- stiff

- stingy

- strange

- studious

- stupid

- thankful

- thorough

- troublesome

- trusting

- ungrateful

- unhurried

- unpatriotic

- useful

- warm

- weak

- wild

- youthful

Intermediate and Advanced

- abrasive

- accessible

- affable

- affected

- agonizing

- aimless

- aloof

- amiable

- amoral

- animated

- anticipative

- apathetic

- apologetic

- arbitrary

- argumentative

- arrogant

- artful

- articulate

- artificial

- ascetic

- asocial

- aspiring

- assertive

- astigmatic

- austere

- authoritarian

- awkward

- balanced

- barbaric

- benevolent

- bewildered

- bland

- blasé

- blunt

- boisterous

- boorish

- bossy

- breezy

- brittle

- brutal

- brutish

- calculating

- callous

- candid

- cantankerous

- captivating

- casual

- caustic

- cerebral

- changeable

- charismatic

- charmless

- chummy

- circumspect

- civilized

- clear-headed

- coarse

- cold-hearted

- colorless

- committed

- communicative

- compassionate

- complacent

- compulsive

- conciliatory

- condemnatory

- conformist

- conscientious

- conservative

- consistent

- constant

- contemplative

- contented

- contradictory

- conventional

- crass

- crude

- cultured

- cunning

- cynical

- dauntless

- debonair

- decadent

- deceitful

- decent

- deceptive

- decisive

- dedicated

- deep

- deferential

- dependent

- depressed

- desiccated

- desperate

- despondent

- determined

- devious

- devoted

- directed

- disaffected

- discerning

- disciplined

- disconcerting

- discontented

- discouraging

- discourteous

- discreet

- disillusioned

- disloyal

- dismayed

- disorderly

- disorganized

- disparaging

- disputatious

- dissatisfied

- dissolute

- dissonant

- distressed

- disturbing

- dogmatic

- dominating

- domineering

- doubtful

- dramatic

- driving

- droll

- dry

- dutiful

- dynamic

- earnest

- earthy

- easygoing

- ebullient

- effervescent

- egocentric

- elegant

- eloquent

- emotional

- empathetic

- encouraging

- enervated

- enigmatic

- enthusiastic

- envious

- equable

- erratic

- escapist

- esthetic

- ethical

- exacting

- excessive

- expedient

- extravagant

- exuberant

- facetious

- faithless

- familial

- fanatical

- fanciful

- farsighted

- fatalistic

- fawning

- feisty

- ferocious

- fickle

- fierce

- fiery

- fixed

- flamboyant

- folksy

- forceful

- formal

- forthright

- fortunate

- frank

- fraudulent

- freethinking

- freewheeling

- frightening

- frivolous

- frugal

- frustrated

- fun-loving

- furious

- gallant

- garrulous

- giddy

- glamorous

- good-natured

- graceless

- gracious

- gregarious

- grim

- guileless

- gullible

- hardworking

- hardy

- harried

- harsh

- hateful

- haughty

- hearty

- hedonistic

- hesitant

- hidebound

- high-handed

- high-minded

- homebody

- honorable

- hopeless

- hospitable

- hostile

- hot-tempered

- humble

- hypnotic

- iconoclastic

- idealistic

- idiosyncratic

- ignorant

- imitative

- immobile

- impartial

- impassive

- impersonal

- impractical

- impressionable

- impressive

- imprudent

- impudent

- impulsive

- inactive

- incisive

- inconsistent

- incorruptible

- incurious

- indecisive

- indiscriminate

- individualistic

- indolent

- indulgent

- inefficient

- inert

- inhibited

- inimitable

- innocent

- inoffensive

- insecure

- insensitive

- insightful

- insincere

- insipid

- insistent

- insolent

- insouciant

- intelligent

- intense

- intolerant

- intrepid

- intuitive

- invisible

- invulnerable

- irascible

- irrational

- irreligious

- irresponsible

- irreverent

- irritable

- joyful

- keen

- lackadaisical

- languid

- left-brained

- leisurely

- liberal

- libidinous

- licentious

- light-hearted

- limited

- logical

- loquacious

- lyrical

- magnanimous

- malicious

- manly

- mannered

- mannerly

- many-sided

- masculine

- maternal

- mawkish

- mealy-mouthed

- mean

- mechanical

- meddlesome

- meek

- melancholic

- mellow

- merciful

- meretricious

- methodical

- meticulous

- miserable

- miserly

- misguided

- moderate

- modern

- modest

- money-minded

- monstrous

- moralistic

- morbid

- muddle-headed

- multi-leveled

- murderous

- mystical

- naive

- narcissistic

- narrow

- narrow-minded

- negativistic

- neglectful

- negligent

- neurotic

- neutral

- nihilistic

- noncommittal

- noncompetitive

- objective

- obliging

- obnoxious

- obsessive

- obvious

- offhand

- old-fashioned

- one-dimensional

- one-sided

- open

- opinionated

- opportunistic

- oppressed

- optimistic

- original

- outrageous

- outspoken

- painstaking

- paranoid

- passionate

- passive

- paternalistic

- patriotic

- pedantic

- perceptive

- perseverant

- personable

- perverse

- pessimistic

- petty

- phlegmatic

- physical

- pitiful

- placid

- planful

- plodding

- polished

- political

- pompous

- possessive

- power-hungry

- precise

- predatory

- prejudiced

- preoccupied

- presumptuous

- pretentious

- prim

- primitive

- principled

- procrastinating

- profligate

- profound

- progressive

- proper

- protean

- protective

- providential

- provocative

- prudent

- psychotic

- pugnacious

- puritanical

- purposeful

- quarrelsome

- questioning

- quick-tempered

- rational

- rawboned

- reactionary

- reactive

- realistic

- reckless

- reflective

- regimental

- regretful

- reliable

- religious

- repentant

- repressed

- repugnant

- repulsive

- resentful

- reserved

- resourceful

- respectful

- responsive

- restless

- restrained

- retiring

- reverential

- rigid

- risk-taking

- ritualistic

- ruined

- rustic

- ruthless

- sadistic

- sage

- sanctimonious

- sarcastic

- scared

- scheming

- scornful

- scrupulous

- secretive

- secure

- sedentary

- self-centered

- self-conscious

- self-critical

- self-denying

- self-indulgent

- selfless

- self-reliant

- self-sufficient

- sensitive

- sensual

- sentimental

- seraphic

- sexy

- shallow

- sharp

- sharp-witted

- shiftless

- shortsighted

- shrewd

- simple-minded

- single-minded

- skeptical

- sober

- sociable

- softheaded

- soft-hearted

- solid

- solitary

- sophisticated

- sordid

- spendthrift

- spontaneous

- sporting

- stable

- steadfast

- steady

- steely

- sterile

- stoic

- strong-willed

- stubborn

- stylish

- suave

- subjective

- submissive

- subtle

- superficial

- superstitious

- supportive

- surprising

- suspicious

- sympathetic

- systematic

- tactful

- tactless

- talkative

- tasteful

- tasteless

- temperate

- tense

- thievish

- thrifty

- thrilled

- timid

- tireless

- tolerant

- touchy

- tough

- tractable

- transparent

- treacherous

- trendy

- unaggressive

- unambitious

- unappreciative

- uncaring

- unceremonious

- unchanging

- uncharitable

- uncomplaining

- unconcerned

- unconvincing

- uncooperative

- uncoordinated

- uncreative

- uncritical

- unctuous

- undemanding

- undependable

- undisciplined

- undogmatic

- unfathomable

- unforgiving

- unimaginative

- unimpressive

- uninhibited

- unlovable

- unmerciful

- unpolished

- unprincipled

- unrealistic

- unreflective

- unreligious

- unrestrained

- unsentimental

- unstable

- unsuitable

- upright

- urbane

- vacuous

- vague

- venal

- venomous

- venturesome

- vindictive

- violent

- virtuous

- vivacious

- vulnerable

- weak-willed

- well-bred

- well-meaning

- well-read

- well-rounded

- whimsical

- willful

- winning

- wishy-washy

- withdrawn

- witty

- zany

List 110. Tone and Mood Words

List 110. Tone and Mood Words

Writers use tone and mood to connect their listening and reading audiences to the story, poem, play, or other work. These two elements of writer's craft are related but are not the same. Both use word choice to create their desired effects. Tone is the author's attitude about the subject, the characters, or the audience. Is the author excited? Indifferent? Annoyed? Tone can be positive, neutral, or negative. In addition to vocabulary, the setting, dialogue style, and other details can also convey tone. Mood is the overall emotion or feeling created in the audience by the author. The author uses descriptive words, setting, and images to create a mood. Does the writing make you happy? Sad? Hopeful? Edgy?

Recognizing tone and mood can aid the discovery of themes in literature. We appreciate writers' talent by the way they create tone and mood and change the mood with plot twists or character behavior. The following lists show words that describe tone and mood. Look for these words and other context clues as evidence of the author's tone and the mood of the writing in stories, poems, plays, speeches, films, and songs. Some words appear on both lists because they can convey an author's attitude as well as create that feeling in the audience.

Positive Tone Words

- admiring

- adoring

- affectionate

- amused

- appreciative

- approving

- awed

- bemused

- benevolent

- celebratory

- cheerful

- comforting

- comic

- compassionate

- complimentary

- conciliatory

- concurrence

- confident

- content

- delighted

- dreamy

- ebullient

- ecstatic

- effusive

- elated

- empathetic

- encouraging

- enthusiastic

- euphoric

- excited

- exhilarated

- expectant

- fervent

- festive

- friendly

- funny

- gleeful

- gushy

- happy

- hilarious

- hopeful

- humorous

- imploring

- innocent

- inspired

- interested

- jovial

- joyful

- laudatory

- light

- lively

- lyrical

- mirthful

- motivated

- mysterious

- nostalgic

- optimistic

- passionate

- playful

- poignant

- proud

- reassuring

- relieved

- respectful

- reverent

- romantic

- sanguine

- satisfied

- self-assured

- sentimental

- silly

- sprightly

- suspenseful

- sympathetic

- tasteful

- tender

- tranquil

- whimsical

- wistful

- witty

- worshipful

- zealous

Neutral Tone Words

- aloof

- ambiguous

- ambivalent

- appraisal

- blunt

- bookish

- calm

- casual

- clear

- contemplative

- deliberate

- detached

- detailed

- didactic

- direct

- distant

- earnest

- educational

- equivocal

- formal

- forthright

- impartial

- indifferent

- indirect

- informal

- instructive

- introspective

- ironic

- journalistic

- learned

- matter-of-fact

- meditative

- moderate

- modest

- multifaceted

- neutral

- nonchalant

- objective

- pedagogical

- pensive

- placid

- profound

- prosaic

- passionate

- questioning

- relaxed

- reflective

- resigned

- scholarly

- serious

- speculative

- straightforward

- tempered

- unambiguous

- uncertain

- somber

- unconcerned

- understated

Negative Tone Words

- accusatory

- acerbic

- admonition

- angry

- annoyed

- antagonistic

- antiquated

- anxious

- apathetic

- apprehensive

- arbitrary

- arrogant

- belligerent

- bewildered

- biased

- biting

- bitter

- bittersweet

- bleak

- bossy

- callous

- caustic

- choleric

- conceited

- concession

- condescending

- confrontational

- confused

- conjecture

- contemptuous

- conventional

- convoluted

- critical

- curt

- cynical

- defiant

- depressed

- derisive

- derogatory

- desolate

- despairing

- desperate

- diabolic

- disappointed

- disdainful

- disliking

- disrespectful

- distasteful

- doubtful

- eccentric

- eclectic

- eerie

- embarrassed

- enraged

- evasive

- facetious

- fatalistic

- fearful

- flippant

- foggy

- foreboding

- frantic

- frightened

- frivolous

- frustrated

- furious

- glib

- gloomy

- gory

- greedy

- grim

- harsh

- haughty

- haunting

- heretical

- holier-than-thou

- hopeless

- horror

- hostile

- idiosyncratic

- impatient

- impetuous

- impulsive

- incredulous

- indignant

- inflammatory

- insecure

- insensitive

- insolent

- irate

- irreverent

- judgmental

- lethargic

- malicious

- melancholy

- mischievous

- miserable

- misgiving

- mocking

- morose

- mournful

- nervous

- obsequious

- ominous

- outraged

- paranoid

- pathetic

- patronizing

- perplexing

- pessimistic

- petulant

- polished

- pompous

- preachy

- pretentious

- psychotic

- quizzical

- resilient

- reticent

- reverent

- ribald

- ridiculing

- sad

- sarcastic

- satirical

- scornful

- sinister

- skeptical

- slick

- sly

- stern

- stinging

- stolid

- stressful

- strident

- sullen

- superficial

- surly

- suspicious

- tense

- tentative

- threatening

- timid

- tongue-in-cheek

- tragic

- trepidation

- underhanded

- uneasy