The Integrative Potential in Negotiations

Uncomfortable with the seemingly adversarial nature of value claiming, people often focus on negotiations as opportunities to create value—to find deals that can enhance the outcomes of all the parties. In this chapter we discuss how this occurs. However, while the primary focus of this chapter is on value creation, keep in mind that the ultimate goal of negotiations is to claim value—to get (more of) what you want!

Value creation in a negotiation has several seemingly self-evident benefits. First, it increases the amount of value that can be allocated between the parties. Think of this as enlarging the bargaining zone—the area between your reservation price and that of your counterpart. In isolation, enlarging the bargaining zone is a good thing: value creation has the benefit of potentially making at least one party better off without hurting the other party.1 Widening the bargaining zone also makes it easier to find a deal that exceeds both parties’ reservation prices thus reducing the likelihood of an impasse.

Value creation has a psychological benefit as well. By improving the deal for your counterpart, you increase his goodwill toward you. Even when you end up with objectively the same amount, he may give you credit for your cooperative engagement.2

For value creation to be possible, a negotiation must have at least one integrative issue—that is, an issue in which the parties value outcomes differently. This type of issue differs importantly from the zero-sum or distributive issues discussed in Chapter 3. With distributive issues, the cost of a concession made by one side exactly equals the benefit of that concession to the other side. Thus, value is created through an exchange but negotiating distributive issues within that exchange only offers parties the opportunity to redistribute that value.

Issues that are easily divisible or are valued for their extrinsic worth are more likely to be distributive while issues where the value is more intrinsic or subjective to an individual are more likely to be integrative. What makes an issue integrative is that it is valued differently by the negotiating parties such that the cost of a concession by one party is less than the concession benefits the other party.

Having a single integrative issue by itself is not sufficient for value creation, however, because a concession still leaves the conceding party worse off (even though by less than the counterpart benefits). Thus, while a necessary condition for value creation is the presence of at least one integrative issue, the receiving party must be a willing to concede on at least one other issue to compensate the conceding party. That additional issue can either be distributive or integrative. In that case, trading an issue that you value less than your counterpart in exchange for concessions on an issue you value equally (distributive) or even more (integrative) than your counterpart creates value. This strategy is called log-rolling (or horse trading), and it involves extracting concessions on issues that are of more value to you and giving concessions on issues that are of less value to you (or preference trades). The point is to realize the integrative potential through value-enhancing trades that get you more of what you want at a “cost” that you are willing to pay.

THE INTEGRATIVE POTENTIAL

Although the principle of value creation is straightforward, creating value in an actual negotiation requires negotiators to assess the relative value of issues for themselves and their counterparts. This is difficult for two reasons. First, many negotiators strongly believe that negotiations are zero sum, leading them to miss the value-creating potential of many negotiations. Second, overcoming this zero-sum presumption requires information to identify integrative issues.

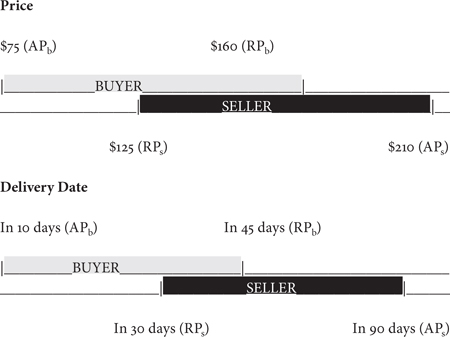

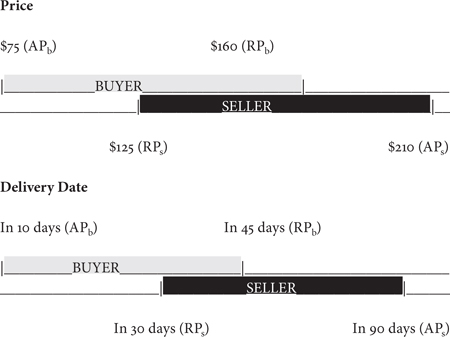

Take our tire example from Chapter 3; let’s see what changes when Thomas and the dealer value the issues of price and delivery time differently. The basic structure of the scenario is the same as before, a bargaining zone on price between $125 and $160 per tire and a delivery date between 30 and 45 days.

The dealer is content to continue using the metric of $2 per day to value the delivery so that these two issues can be evaluated on the same scale. However, Thomas now assigns a different value to the delivery date: an early delivery is now essential. In fact, he is willing to raise his price by $10 per day to obtain as early a delivery as possible.3

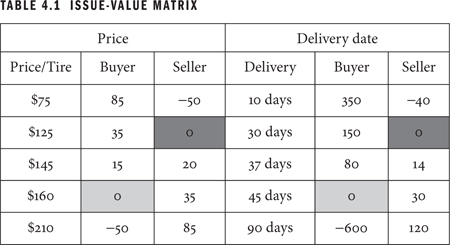

This asymmetry in the valuation of the delivery date changes the total value of different combinations of price and delivery dates. Using the dealer’s perspective of price and delivery dates as a starting point, the value of an earlier delivery swamps the value available in the price range under discussion from Thomas’s perspective. Table 4.1 shows how the issue-value matrix looks. Note that Thomas’s reservation price on each issue is highlighted in grey; while the reservation price of the seller is highlighted in black.

In the split-the-difference example ($145 and 37 days), the deal is worth $95 to Thomas ($15 + $80) and $34 to the dealer ($20 + $14), for a total of $129. However, had the parties taken advantage of the asymmetry in the value of the delivery date, the outcome would be quite a bit different—considerably more value would be created that could be claimed by the parties.

Recall that Thomas is willing to pay $10 more per day for the tires to be delivered sooner. In contrast, the dealer requires only $2 per day to speed up the delivery. Because Thomas and the dealer value the delivery date so differently, the best deal here would be a combination of a high price per tire associated with a delivery date within thirty days. Both parties are better off when Thomas is willing to give concessions on price while receiving concessions resulting in an earlier delivery time.

Consider how the integrative value of the deal is affected by this tradeoff. If Thomas were willing to go to his reservation price on price while the dealer went to her reservation price on delivery, the deal would be worth $150 ($0 + $150) to Thomas and $35 ($35 + $0) to the dealer, resulting in $185 in total. They have significantly enlarged the pie (from $129 to $185), and each has claimed some of that additionally created value.

Yet the dealer, in this case, is not extracting as much value as Thomas. Obviously, this would change if the dealer realized how valuable early delivery was to Thomas. If she paid attention, she might realize that delivery date is an integrative issue. However, Thomas should avoid divulging how much he actually values an early delivery as this would induce the dealer to demand more. Going back to the idea of packaging issues to achieve a reservation price, the dealer could propose to get the tires delivered within the next ten days (the buyer’s aspiration price) if Thomas were willing to pay the dealer’s asking price of $210. If the parties were able to agree to a $210 price and delivery within ten days, the dealer would realize $45 ($85 − $40) of value while Thomas would realize $300 (−$50 + $350) of value. Hence, the integrative value in this situation would increase to $345.

So a better deal can be reached—even though it might violate the reservation price of individual issues—so long as the benefits received in exchange for this violation on price are sufficiently valuable. Since Thomas is in a big hurry to get the tires (reflected in his valuation of the delivery issue), he might be willing, even eager, to take this deal; in the aggregate, after all, it creates $300 in value for him even though it violates his reservation price on price per tire. The same is true for the dealer. Given the dealer’s concern with price, she should be willing, even eager, to deliver the tires in ten days even though the delivery time violates her reservation price on that issue, because the deal gives her $45 in combined value.

As this scenario demonstrates, value creation hinges on the parties’ ability to discover that they value issues differently and to use that information to propose packages that make them better off. Often this isn’t easy—but if it’s accomplished, the value available to be claimed by one or both parties can be much greater than in a purely distributive negotiation.

Thus, the challenge of realizing the integrative potential of a deal requires that you understand the issues and your preferences as well as the issues and preferences as valued by your counterpart. This is important for three reasons. First, it provides information that allows you to agree only to deals that do not violate your package-level reservation price. Second, it allows you to make trades that create value. Finally, it allows you to claim more of the value that has been created.

But herein lies the danger. Realizing how highly Thomas values an early delivery allows the dealer to extract more value from Thomas. By revealing that each delivery date is worth $10 per tire to him, Thomas and the dealer may find a deal that maximizes value—but that value may be claimed entirely by the dealer.

In negotiations not only can you gather information during the preparation phase, but also the negotiation itself can provide numerous opportunities not only to verify the information you gathered in the planning phase but also to expand your knowledge. In the next section, we demonstrate strategies and tactics that allow you to exchange information while minimizing the impact of this information exchange on your ability to claim value.

THE INFORMATION-GATHERING CHALLENGE

It seems reasonable to expect that increasing the size of the pie will allow you to claim more of it. But is that necessarily true?

To create value in a negotiation the parties must share information that will allow them to identify the issues; determine which are distributive, integrative, and congruent; and for integrative issues, allow trades that reflect their respective differences in value. Yet sharing too much information (or the wrong kind) can put you at a competitive disadvantage. Specifically, value creation does not change either party’s reservation price. As a result, your counterpart could claim all the value created (and then some) if she could infer your reservation price from the information shared.

From an economics perspective, sharing information in the value creation process creates two challenges: First, separating the negotiation into a value-creating phase and a value-claiming phase runs the risk of limiting the value you can claim. Once both sides know the size of the pie, the negotiation becomes distributive (zero sum), and value claiming becomes contentious: whatever you get comes out of your counterpart’s pocket. Second, the negotiator who first realizes the value differential between the parties has an increased capacity to claim the value created. To illustrate this first challenge, consider the implications of a full-disclosure strategy.

Sharing information indiscriminately is potentially disastrous: If such sharing behavior is not reciprocated, you run the risk that if a deal is consummated, all you would claim is your reservation price. But when all information is shared by both parties, you may be able to create the largest pie possible, but you almost certainly won’t be able to claim more than half of it because your counterpart will be attempting to claim as much as possible as well. Perhaps you don’t see that as a problem. However, if, for example, you bring more critical resources to the deal than those brought by your counterpart, you may find yourself less than satisfied. Moreover, attempting to extract more than an equal split will result in an extremely contentious process, so much so that one party may choose an impasse over losing her claim to equal distribution. In short, when all the information is shared, then the only task left is to fight over who gets what. The negotiation becomes adversarial—it is only about value claiming.

To illustrate this challenge, suppose the dealer discovers that delivery time is five times more important to Thomas than it is to her. For every day earlier, Thomas is willing to pay $10, whereas originally the dealer would have been willing to charge only an additional $2. With this knowledge, the dealer can offer Thomas earlier delivery for $9 per day. From Thomas’s perspective, this offer nets him an additional $1 per day. The outcome exceeds his reservation price—but not by much, and most of the value created ends up in the dealer’s pocket.

It’s important to understand, too, that not all information is equally strategic. Revealing information that allows the parties to figure out which issues are integrative may be necessary for value creation; revealing the exact integrative potential for these issues is highly strategic, because understanding how each party values the integrative issues provides a strategic advantage in value claiming. (This principle will be emphasized in Chapter 6.)

The bilateral full-disclosure strategy is great if you are certain that you are both happy with splitting the resources equally and will share all the information openly. This is much more likely to be the case when you are negotiating with counterparts with whom you have a long-term relationship. In fact, research demonstrates that if the relationship is an important issue, then an equal split of the value that is created is exactly what most people want.4

But what if the full-disclosure strategy were unilateral? For example, while you reveal all your information, your counterpart misrepresents her interests. Knowing all your information, she can find the deal that maximizes value creation in the negotiation. But what part of that value will you get? The deal will likely be struck just at, or slightly in excess of, your reservation price. After all, your counterpart, knowing all your information including your reservation price, could fashion a deal that provides you with the absolute minimum that you are willing to take.

In conclusion, since there is no way for you to verify whether your counterpart is speaking or obfuscating the truth, the full-disclosure strategy is dangerous because you may well end up with not much more than your reservation price. This is particularly true if this were a one-time negotiation because your counterpart need not take the long-term consequences of her behavior into account.

So, if you want to claim more value, what other options will protect your value-claiming potential? Next, we show you how you can reduce the general risk associated with sharing information.

MITIGATING THE RISK OF INFORMATION EXCHANGE

In some situations information exchange can be relatively safe: for example, when you negotiate among friends. Ongoing relationships such as friendships inhibit one party’s short-term exploitation of the other for strategic advantage.

Yet there are reasons why you might withhold information even from your friends. Perhaps you are concerned about generating conflict if you push too hard—paradoxically this may include additional information that might make you both better off. So rather than engaging in that hard work, you opt for a quick, easy solution that avoids conflict even if it significantly reduces the potential value created. In such a scenario, the relationship has actually made information sharing more difficult. The mutual desire to maintain the comfort level of the interaction often results in sacrificing the quality of the deal.

From our perspective, there is nothing wrong with accepting a bad deal for the good of a relationship, as long as it is done intentionally. Yet easy-solution strategies are often adopted because of parties’ aversion to conflict rather than a thoughtful assessment of what they would lose or gain.

Just as negotiating with friends and partners can be difficult, negotiating with strangers (or in a one-time deal) has its challenges, as well. You are likely to know less about which issues matter and how much they matter to a stranger, making the prenegotiation preparation more challenging. In addition, you may be less adept at interpreting the information conveyed by strangers during the negotiation. And the process of sharing information may be riskier, as well. First, because there is less chance of a future interaction, the cost of misrepresentation is much lower. As a result, each party should be more suspicious when interpreting information and triangulate it with other evidence to assess its reliability. Second, value claiming will likely be more contentious, because there is no benefit to creating good will or long-term reciprocity when (in the context of the negotiation, at least) there is no tomorrow.

Finally, value creation is hampered: you and your counterpart are more likely to expect the issues to be distributive, thus justifying more aggressive strategies such as exaggerating, misrepresenting, and withholding information.

But regardless of whether you negotiate with friends or strangers, high aspirations—or high expectations—are beneficial. Moreover, there is another necessary condition: you need to be ready to problem-solve—that is, to craft proposals that take advantage of the asymmetries in preferences between you and your counterpart to create value without unnecessarily sharing information that could damage your ability to claim value. This requires focused information gathering and thoughtful sharing.

In the next section, we consider ways to gather and share information in a negotiation. Some of these strategies are better at protecting your value-claiming potential while others are more conducive to value creation. Choosing ways to share information is a strategic choice—and the right strategy depends on the particular situation, your counterparts, and your goals.

CREATING AND CLAIMING VALUE: AN EXAMPLE

This example continues our vehicular theme, but gives Thomas and the tire dealer a break; rather, it concerns Margaret’s real-life purchase of a new car. This negotiation appears—at first glance—to be very similar to our first example of Thomas and his tires: it concerns a single, distributive issue (price). Yet by focusing on issues other than the dollar value of the car, Margaret was able to create considerably more value and get a better deal.

Margaret could have conceived of the transaction as simply an exchange in which she was willing to trade cash for a new car. Naturally, Margaret wanted to pay as little as possible for the car while the dealer wanted to extract as high a price as possible. The dealer set a price (i.e., the first offer); if Margaret willingly accepted it, then value has been created by the exchange because Margaret must value the car more than she values that cash (and vice versa for the dealer). If, on the other hand, Margaret were successful in negotiating the dealer’s offering price, then she would have managed to claim additional value—and the dealer would have lost value, all by negotiating over a single, purely distributive issue.

Yet within this exchange there was opportunity to create more value, so long as Margaret and the dealer were willing to include additional issues in the negotiation—especially issues they valued differently (i.e., integrative). Indeed, before she started to negotiate, there were a couple of issues that Margaret wanted to discuss that had the potential to increase the value of the deal to her.

The first issue was trading in her ten-year old SUV. She could have sold it to a private party, but she placed a premium on selling it quickly and was willing to sacrifice some money for the convenience of having the dealer take the car as a trade-in. In addition, by trading in her old car, she would also save on the sales tax on her new car, because its final purchase price (on which sales tax is assessed) would be reduced by the value of the trade-in. Having done her homework, Margaret believed that if she were lucky she could get $7,500 through a sale to a private party; however, the dealer was only willing to pay $5,000. From Margaret’s perspective, the convenience of leaving her old SUV at the dealership was worth more than the potential $2,500 she would forgo by not selling it herself. Knowing this, we can calculate that Margaret values every dollar that the dealer offers her for the car at least at $1.50. The extra fifty cents per dollar represents the cost of the hassle of selling her car privately as well as the additional taxes she would have to pay.

A second issue with value-creating potential was the asymmetric value associated with the cost of the routine maintenance. The value of that maintenance was more to Margaret than the costs to the dealer. Therefore Margaret was willing to pay a higher price to extend the length of time that the dealer would cover routine maintenance.

Fortunately, there was another issue that the dealer cared more about than Margaret: a high rating of the dealership on the customer-satisfaction survey conducted by the automobile manufacturer. Thus the dealer extended the length of time that the warranty covered routine maintenance while Margaret agreed to convey her satisfaction about the interaction in the strongest possible terms. Thus, value was first created by the sale itself: the trade-in, increasing the coverage of routine maintenance, and ensuring Margaret’s satisfaction with the process were all ways in which additional value was created.

We have been focusing so far on two related mechanisms for value creation—trading among issues that you and your counterpart value differently (or log-rolling)—and adding issues—making it easier to find value-enhancing trades. In the final section of this chapter, we will focus another useful method to create value—contingency contracting.

CONTINGENCY CONTRACTING: PLAYING ON YOUR DIFFERENCES TO CREATE VALUE

In some negotiations, the true value of an outcome can only be known at some time in the future. Think about executive salaries as a compensation for managing the firm well or compensating a television producer for obtaining high the ratings of his television shows. In each situation, the actual value of the issue cannot be determined at the time of the negotiation. The ultimate value may be a function of how the contract creates incentives for future effort by the parties as well as the differential beliefs that each party has about the future.

Because such issues are difficult to value, they are good candidates for inclusion in contingency contracts. Think about contingency contracts as bets.5 The executive believes that she can do a great job at running the firm. By accepting the compensation in stock options, she is betting that the future stock price will be higher than the exercise price of her options, while the producer’s compensation will increase as his television show is watched by more people (higher ratings mean more viewers and more advertising revenue).

Contingency contracts are challenging to design and typically appear at a relatively late stage in the negotiation—often as a last effort to avoid an impasse. To see their challenges and benefits, let’s explore how a contingency contract saved Thomas a lot of money on his new home.

Thomas had interviewed a number of architects with excellent reputations in Chicago’s North Shore. After much deliberation, he and his wife Franziska chose one and then spent about eight months designing the home they had always wanted. Of course, the design had to be completed before the price could be negotiated. When both Thomas and Franziska were both relatively comfortable with the design, the builder (Out-of-this-World Architectural Design—OAD6) priced the construction of the house they had designed.

While Thomas and Franziska negotiated with the architect, another change occurred. From the time when the first price was proposed to the point of the negotiation, the economy had contracted, and prices on most building materials had dropped precipitously. As you might imagine, Thomas wanted the benefit of that price reduction. The OAD contracts person, Rod, held the position that any benefit from cost reductions from the subcontractors belonged to OAD (interesting to note that OAD was not expecting to absorb the subcontractors’ cost increases—those would be absorbed by the subcontractors themselves). Thomas thought that the amount of potential cost savings could be very large; after all, the initial price points had been solicited in early 2008—in a much different economic environment from late 2009. After some heated discussion, the parties reached a stalemate with both parties seriously considering calling off the entire project.

One evening, after a long day of discussions for both parties, Rod left with this parting comment: “I cannot believe that you are going to walk away from this deal for a dispute worth less than $3,000.” Thomas was stunned—for two reasons. One, he had calculated the potential benefit as being much higher than Rod’s comment indicated. Second, if he were going to walk away from this deal for a mere $3,000, so was Rod and OAD. After all, negotiation is an interdependent process. As such, Thomas was sure that the actual benefit had to be higher than $3,000 or Rod’s behavior would make no sense. The next morning, Thomas contacted Rod with the following proposal: OAD could have the first $3,000 in cost savings and then they would split the remainder of the savings: 25 percent would go to OAD and 75 percent to Thomas and Franziska. Thomas knew that if Rod were accurately representing his true beliefs about the size of the cost savings, then this deal should be very attractive because it gave him 100 percent of what he calculated would be the potential savings: OAD would be kept whole. However, if the cost savings were much larger than $3,000 (as Thomas suspected), then this deal would look much less attractive to Rod. After a few more rounds of discussion—which included the principal of the firm—a deal was finally struck. The contingency contract was modified to a 50-50 split between Thomas and OAD of any cost savings beyond the first $3,000. Thus, it seems that this $3000 figure was, in Rod’s mind, a real and significant barrier to an agreement.

Thomas had been the one to propose increasing OAD’s proportion of the benefit from 25 percent to 50 percent—but he was not simply being generous. Rather, he wanted OAD to seek out cost reductions whenever possible. As such, he was concerned that a 25–75 split would not give them sufficient incentives to press their subcontractors, so he proposed a 50-50 split to which OAD happily agreed—and the construction on Thomas’s new home began.

As this example illustrates, contingency contracts make sense when the parties differ in their expectations about the size of the future benefit (as Thomas and Rod did) or when they differ in their risk profiles or time horizons. Such differences result in the parties valuing these factors differently, thereby creating integrative potential. However, remember that contingent contracts reflect the parties betting on different future outcomes, and they both cannot be right. For at least one—and maybe both—the deal they expect might end up being quite a bit different from the deal they actually get.

In deciding whether to propose a contingency contract, there are at least three criteria to consider. First, contingency contacts require that the parties have a continuing relationship—that both parties are around when it comes time to settle up.

Second, contingency contracts should be transparent. Consider the differing levels of transparency if your compensation is based on company profits or company sales. Sales are a much more transparent metric than profits because it is easier to determine when a sale occurs than when profit is realized. In addition, organizations have considerable leeway in defining what expenses should be deducted from revenues to compute profit. There are numerous stories about successful films in Hollywood that have never achieved profitability, often told by movie stars and backers who agreed to contingency contracts that kicked in once “profitability” was reached.

Third, contingency contracts must be enforceable. Part and parcel of the first two criteria is the requirement that both parties have the ability to insure that the bet gets paid. Think about the level of interest that credit card companies charge high-risk customers. This is a contingency contract. The credit card company will loan you money to purchase a variety of goods and services. In exchange, they expect this loan to be repaid at a specified future date and with interest. The specific interest rate depends on how the bank assesses the risk of the enforceability of the contract. Do you have the means to repay the loan? Will you still be around to pay the debt or to go to court if you fail to pay? If this or the other two criteria cannot be met, then it’s best for you to stick to more standard, fail-safe ways of creating value in a negotiation.

SUMMARY

Value creation is an important aspect of negotiation and is intimately connected to value claiming. Simply put, creating value allows you to claim it—to get more of what you want. Value creation comes in two forms: the value that is created by the exchange itself, and the value represented by the integrative potential of the multiple issues that may be valued differently by the parties.

In considering value creating opportunities, remember:

1. Value creation is in the service of value claiming. What really counts is how much value you can get out of your negotiated interactions.

2. While it may be easier to claim more value when more value is created through the interaction, the information exchanged to create value may handicap your ability to claim value.

3. To search for issues that you and your counterpart value differently because having multiple issues that are valued differently can increase the value of the negotiation.

4. Setting your reservation price at the level of the deal or package rather than at the issue level facilitates your ability to create value by increasing the potential trades to which you can agree.

5. Figuring out which issues are valued differently—and how differently they are valued—provides an important window into the value-creating opportunities.

6. When different expectations of future events, risks, or time threaten the agreement, consider exploring a contingency contract where parties can bet on their beliefs.

7. If considering a contingency contract, only do so if the following three conditions exist: (1) there is a continuing relationship between the parties, (2) the contract is based on transparent aspects of the deal, and (3) the contract is enforceable.

In these first four chapters you have explored the basic structures of a negotiation. In the next chapter, we walk you through the planning and preparation process, with a focus on identifying what you want and, equally important, assessing what your counterpart wants. The information that you gather during the planning process is critical to success because in negotiation, what you don’t know can really hurt you.