7

P.T. Barnum’s Secret for Making Unknowns Famous and Himself Rich

I am indebted to the press of the United States for almost every dollar which I possess and for every success as an amusement manager which I have ever received. The very great popularity which I have attained both at home and abroad I ascribe almost entirely to the liberal and persistent use of the public journals of this country.

—P.T. Barnum, 1891, five days before he died

P.T. Barnum had never heard Jenny Lind sing, but he had heard of her reputation and he was willing to gamble everything he had on that reputation.

The plain-looking 29-year-old Swedish soprano, hair parted in the middle, a nose like a Nordic potato, never known to wear makeup, was the talk of Europe. Critics said her voice sounded like a nightingale. People who watched her sing felt they were in the presence of an angel. Royalty paid homage to her. Queen Victoria loved her. All of Europe treated her like a celestial being. People called her the Swedish Nightingale. Yet few in America had ever heard of her.

Barnum smelled an opportunity, but what he would need to succeed was yet another ring of power.

Barnum Gets Chilling News

Despite everyone telling him he would fail, Barnum went into debt in order to bring Lind to America. He was confident that the reviews he had heard about her would mean money in the bank to him. One day, however, he was hit with news that sent a cold shiver to the very marrow in his bones.

He was having a casual conversation with a door man when he mentioned he was bringing Lind to America. The doorman asked, “Is she a dancer?”

That’s when Barnum knew he had his work cut out for him. He was bringing the greatest operatic soprano in the world to America in only six months and the average American had no idea who she was. Virtually every bank and investor had told him he would fail. After all, his experience was in displaying questionable curiosities and running a museum, not in managing a legitimate entertainer like the great Jenny Lind. Barnum had to educate the public fast.

Lindomania

He did. He hired 26 reporters to feed the media news stories about Lind, her talents, her arrival, her character. He even had Lind give a farewell performance in England so it could be reported to the U.S. papers.

As a result, over 30,000 people met Lind at the docks in New York when her ship arrived. Over 20,000 people followed her to her hotel, waiting to catch a glimpse of her. Within a short time, there were Jenny Lind songs and polkas, gloves, bonnets, riding hats, shawls, robes, and even Jenny Lind cigars, chewing tobacco, and perfume.

Barnum promoted Lind so heavily that he feared the worst. After all, he had never seen or heard her sing. What if the public hated her?

“... I confess that I feared the anticipations of the public were too high to be realized, and hence that there would be a reaction after the first concert,” Barnum wrote in his autobiography, “but I was happily disappointed. The transcendent musical genius of the Swedish Nightingale was superior to all that fancy could paint, and the furor did not attain its highest point until she had been heard.”

The press went crazy. A writer for Holden’s Magazine advised, “Sell your old clothes, dispose of your antiquated boots, hypothecate your jewelry, come on the canal, work your passage, walk, take up a collection to pay expenses, raise money on a mortgage, sell ‘Tom’ into perpetual slavery, stop smoking for a year, give up tea, coffee and sugar, dispense with bread, meat, garden sass and such luxuries—and then come and hear Jenny Lind.”

Barnum had used the ring of power that he often said could make any man rich—publicity.

Barnum Gets Respectable

Barnum’s giant gamble became one of his greatest accomplishments. Promoting Lind gave him respectability. He was no longer the shameless showman who exhibited an ugly mermaid. He was now the man who introduced the great Jenny Lind to America, and as a result, both he and Lind became independently wealthy.

Don’t think Barnum had it easy, that all he did was offer a diamond to the public and they lined up to touch it.

First, Lind was virtually unknown in America when Barnum signed to bring her here.

Second, under Barnum’s management Lind’s concerts averaged $7,496 a show, more than six times the highest income of the most successful performer of the day. However, when Barnum and Lind split up and she tried managing her own concerts, she failed. Attendance of her concerts grew smaller and smaller. She could not get the crowds to come and see her, yet she was the same person with the same wonderful voice.

Finally, she quit. Within a few months she left America, and very few saw her ship leave dock.

The Value of Publicity

I learned the value of advertising your business when I researched Bruce Barton, cofounder of the BBDO ad agency, for my book, The Seven Lost Secrets of Success. Barton said you had to advertise consistently because “You aren’t talking to a mass meeting, you’re talking to a parade.” I discovered all the different ways to advertise a business when I was writing my book for the American Marketing Association, The AMA Complete Guide to Small Business Advertising, but it wasn’t until I began researching this book that I realized the full power of publicity.

I learned that advertising wasn’t enough. I learned that you had to have an integrated marketing plan to achieve success. Barnum was a master at it. He knew that with strategic publicity you could get people to line up at your door to see anything you wanted to show them. He used publicity to get people to see a little boy he renamed General Tom Thumb. He did it again with an elderly black woman he claimed was the nurse for the father of our country. And he did it with Jenny Lind.

How did he use this particular ring of power? And how can you implement these methods today, to bring business to your own door?

Elssler’s Secret

Although Barnum was an acknowledged genius at generating publicity for his businesses, he didn’t create every technique he used. He was wise enough to learn from others. While still a young man, years before he tasted success running the museum, he found a mentor and witnessed the creation of the world’s first superstar.

Jenny Lind was not the world’s first celebrity. That distinction went to Fanny Elssler, a ballerina. Now, stop and consider how you might promote a ballerina in the 1800s in America. That century was a time of farming, growth, stress, sickness, poverty, poor cultural appreciation, ugly wars on our own land, and slavery. Who really cared about some foreign dancer hopping across a stage?

But publicity can work wonders. Elssler was managed by Chevalier Henry Wikoff, who used puff pieces of publicity to urge the media to write about his client. He also networked relentlessly, arranging for Elssler to perform before the social elite, and then seeing that each performance was covered by the press.

This creative manager didn’t stop there. He also held the first auction for the tickets to Elssler’s opening public performance. By the time Wikoff had orchestrated public enthusiasm for his dancer, there was Elsslermania across the land. People were eager to spend money to see this now-famous ballerina.

Barnum watched all of this with great fascination. He “... gave her manager the credit for doing what I had considered impossible, in working up public enthusiasm to fever heat.” In later years, Barnum used the same publicity techniques to promote Jenny Lind. He learned from watching a master.

Toilet Paper Ends World War I

If you want to learn how to get publicity for your business, get a mentor. Barnum learned from watching Wikoff. You can learn in the same fashion. Find a legend and study his (or her) methods. One of my own heroes in the publicity business was a man who helped stop World War I by giving away toilet paper.

“Harry Reichenbach was the greatest single force in American advertising and publicity since P.T. Barnum,” wrote David Freedman, Reichenbach’s co-author, in Phantom Fame: The Anatomy of Ballyhoo.

Reichenbach worked as a circus press agent at the turn of the century, as a promoter for silent films, and as a propagandist for the first World War. His publicity stunts were jaw-dropping in cleverness as well as effectiveness.

When Reichenbach wanted to get an unknown actor hired at a high salary, he filled his pockets with two thousand pennies. He and the actor then began a long walk to the producer’s office, dropping pennies along the way. At first only children picked up the coins, but then adults started following and gathering pennies as well. Of course, this was in the early 1900s, when pennies were worth picking up.

By the time Reichenbach and his client reached the producer’s office, a mass of people stood behind them. When the producer looked out his window and saw the parade of smiling people behind the unknown actor, he couldn’t help but feel he was about to hire a popular entertainer. Little did he know that no one in the crowd had ever heard of the actor before.

To promote an early Tarzan movie, Reichenbach had someone check into a hotel under the name of “T. R. Zann.” He then had a lion delivered to his hotel room. Yes, a living, breathing, terrifying lion. The resulting chaos achieved wide press coverage. In every article, the name T. R. Zann was mentioned during the same week that the movie The Return of Tarzan hit theaters.

During World War I, Reichenbach created a diploma that the Allies dropped by plane over German lines. The diploma gave any German soldier, upon surrender, status as a prisoner with officer rank. The back of the diploma listed the benefits: bread and meat to eat every day, cigarettes to smoke, a delicing comb, and 24 sheets of toilet paper a day.

About 45 million diplomas were dropped over enemy lines during World War I. Thousands of Germans grabbed the offer and put down their weapons. The German army became so concerned that they passed a law making it a capital offense to pick up any paper on the battlefield. In short, bend over and get shot. This brilliant scheme worked because what the German soldiers wanted, more than anything else, was toilet paper.

“Publicity is the nervous system of the world,” Reichenbach said in 1930, shortly before he died. “Through the network of press, radio, film and lights, a thought can be flashed around the world the instant it is conceived. And through the same highly sensitive, swift and efficient mechanism it is possible for fifty people in a metropolis like New York to dictate the customs, trends, thoughts, fads and opinions of an entire nation....

“From Prohibition to hair-dressing and from a national peace policy to a girl’s pout, the mass is always a magnified reflection of some individual.”

Barnum was such an individual in the 1800s. Reichenbach filled his shoes at the turn of the century. Until 1995, Edward L. Bernays helped push the buttons of publicity to make the public do what he wanted.

The Terrifying Bernays

Edward L. Bernays was the founder of public relations, a nephew of Freud, and the man Hitler tried to hire to promote his cause.

A friend of mine described reading the books by Bernays as “terrifying.” He added, “It’s as though Bernays was from another planet and knew how to pull our strings.”

Bernays once wrote, “. . . While most people respond to the world instinctively—without thought—there have been an ‘intelligent few’ who have been charged with the responsibility of contemplating and influencing human history.”

You can count Bernays as one of those early and few gladiators of publicity. He promoted World War I, made the fashion world learn to love the color green so Lucky Strike cigarettes, which had green on their packaging, would be acceptable, and changed the entire country’s attitude toward women smoking with a now famous publicity stunt.

In the 1920s he hired beautiful fashion models to march in New York’s Easter parade, each lady waving a lit cigarette and wearing a banner that said it was a “torch of liberty.” Overnight, women began to smoke, and Bernays’s client, the American Tobacco Company, got rich.

In the 1970s, when Bernays learned that smoking caused lung cancer, he used his talents to create an antismoking movement and fought to have tobacco ads removed from radio and television.

Bernays lived to be 102, and he has been considered one of the 100 most important Americans of the twentieth century. In 1928, Bernays wrote in Propaganda, “The business man and advertising man is realizing that he must not discard entirely the methods of Barnum in reaching the public.”

One of the people who met Bernays was another publicity wizard: Aaron Cushman. He promoted Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis, The Three Stooges, and business and political giants. Aaron once told me that his favorite Bernays quote was, “Don’t send out news releases, send out news stories.”

Whether you choose Barnum, Bernays, Reichenbach, Cushman, Wikoff, or some other publicity giant as your role model, find a publicity master to learn from. Read their books. Study their methods. Imagine what they might do if they were running your company, and implement what you feel will work in your own business.

Before we move on, let’s meet yet another Barnum-like publicist.

The World’s Greatest Hoaxer

One of my favorite media mavericks is Alan Abel. He’s been called the World’s Greatest Hoaxer. As a jazz drummer turned master spoofer, Abel appeared in a great number of publications and television shows. He is best known for his satirical spoof SINA, the Society for Indecency to Naked Animals, a tongue-in-cheek crusade for the purpose of clothing all pets for the sake of decency. It ran for five years, upsetting some people and delighting others.

Why did this man turn to such ridiculous ideas?

Truth is, Abel was a struggling comedian in the 1950s.To make himself stand out in the crowd, he began to do wild things and create wild events. I love his inventive mind. He once organized a campaign to elect Yetta Bronstein, said to be a Bronx housewife (actually Abel’s wife), U.S. president. He also got the media interested when he announced the first International Sex Bowl in 1969.

According to Alex Boesce, in The Museum of Hoaxes, Abel hired himself out in the 1970s as a professional hoaxer who would give strange speaking engagements to advertising executives. In Abel’s hilarious autobiography, The Confessions of a Hoaxer, he states those talks were titled “The Fallacy of Creative Thinking.”

In 1979 Abel staged his own death from a heart attack near the Sundance Ski Lodge. He hired a fake funeral director to collect his belongings and his widow notified the New York Times. The Times published a long obituary (a rare example of a premature obituary). Three days later Abel held a news conference to announce the “reports of my demise have been grossly exaggerated.” The Times published a retraction the next day, for the first time in its history.

In 1997 Abel invented a special but odd gift: a wrapped pint of urine allegedly from celebrity Jenny McCarthy. The product was supposedly offered in the name of CGS productions, with a contact named Stoidi Puekaw (“Wake up idiots” spelled backwards). The star’s copyright lawyer threatened to sue. Abel’s pun was based on an appearance by McCarthy in a shoe commercial where she was seen sitting on a toilet.

Abel also ran for Congress on a platform that included paying congressmen based on commission, selling ambassadorships to the highest bidder, installing a lie detector in the White House and truth serum in the Senate drinking fountain, requiring all doctors to publish their medical school grade-point averages in the telephone book after their names, and removing Wednesday to establish a four-day work week.

At the 2000 Republican Convention in Philadelphia, Abel introduced a volatile campaign to ban all breastfeeding because “it is an incestuous relationship between mother and baby that manifests an oral addiction leading youngsters to smoke, drink and even becoming a homosexual.” After 200 interviews over two years, Abel confessed the hoax in U.S. News and World Report.

Abel knew that getting the media’s attention got him attention. He went from unknown comedian to fame. Today there is a documentary about him, called Abel Raises Cain.

Barnum would have loved him.

How to Get Free Publicity

In The Humbugs of the World, Barnum explains how Pease’s Hoarhound Candy became a hot seller in a very unusual way:

“In the year 1842, a new style of advertising appeared in the newspapers and handbills which arrested public attention at once on account of its novelty,” Barnum wrote. “The thing advertised was an article called ‘Pease’s Hoarhound Candy’; a very good specific for coughs and colds.”

Pease would read the newspapers to learn what was happening in the country, and then write news commentaries that ended up cleverly and illogically slipping in a sales pitch for his candy. Barnum explains:

Mr. Pease’s plan was to seize upon the most prominent topic of interest and general conversation, and discourse eloquently upon that topic in fifty to a hundred lines of a newspaper-column, then glide off gradually into a panegyric of “Pease’s Hoarhound Candy.” The consequence was, every reader was misled by the caption and commencement of his article, and thousands of persons had “Pease’s Hoarhound Candy” in their mouths long before they had seen it!

If I were practicing Pease’s method in this book, I would suddenly inject a line such as “Read Joe Vitale’s other books, too” whenever I felt like it, not caring if the line fit with the rest of the chapter.

Pease made a fortune, according to Barnum. Although no business person would dare such a sly maneuver today, Pease was on the right track.

In order to get publicity for your business, you can tie your business to current news. Pease did this, but in a deceiving way. Today you can find descendants of Pease’s method wherever you see an advertisement designed to look like a newspaper editorial. This works because people tend to trust news sources—radio, television, newspapers, magazines, and their reporters—over ads.You have to advertise (one of the other rings of power) to be able to fully state your message, but you also need to be associated with news to legitimize your business.

How Barnum Made News

Basically you must have news, invent news, or associate your story to news in order to grab the busy media. They don’t care about your business until you give them a reason to care, and a news-oriented reason at that.

In the middle 1800s, when the country was obsessed with Darwin’s theories and people wondered about evolution, Barnum displayed a black dwarf and billed him as “What Is It?” His copy asked, “Is it a higher order of monkey? None can tell!”

Although most of us today would recoil at such a racist display, people in the 1800s eagerly bought tickets to see if they could tell if this curiosity was the missing link in evolution. Most people didn’t realize that “What is it?” was really William Henry Johnson, a lifelong friend of Barnum’s. Why did people line up to see Johnson? Because Barnum tied the show to then current news.

Barnum also received publicity when he showed Maximo and Bartola, “The Aztec Children,” said to represent a lost race. Barnum had a 40-page booklet printed, complete with endorsements from scientists, to offer the public and the media. Again, this was tying his business to current news interests, because people were very interested in evolution and lost races.

When the country was talking about John Fremont, an explorer who was lost, Barnum displayed an unusual horse that he claimed the explorer had found. Because Barnum tied his display to current news, the people paid attention to his Woolly Horse.

When Barnum was showing Joice Heth, he clearly pointed out that she had been nurse to George Washington, tying his offering to news every patriotic American would be interested in.

When the Civil War was in full swing, Barnum hired men, women, and children who had tasted battle. He showed Robert Hendershot, the 11-year-old Drummer Boy; he displayed Major Pauline Cushman, the actress turned spy; and he hired Samuel Downing, a 102-year-old veteran of the American Revolution. Barnum also showed what he called patriotic dramas twice a day in his Lecture Room. And when Lincoln’s wife and son visited the museum, Barnum, of course, let the press know.

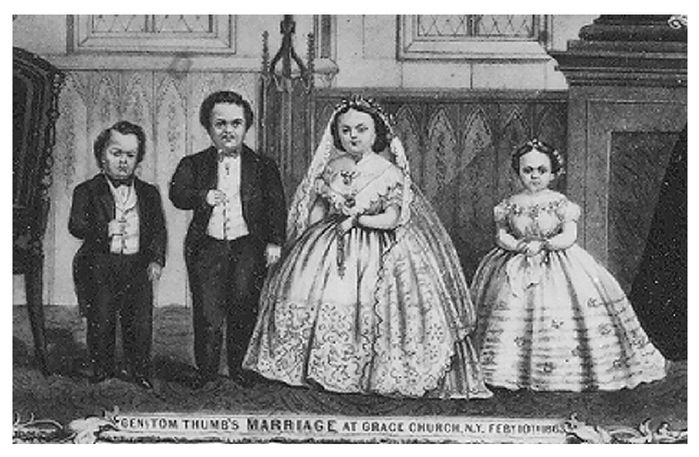

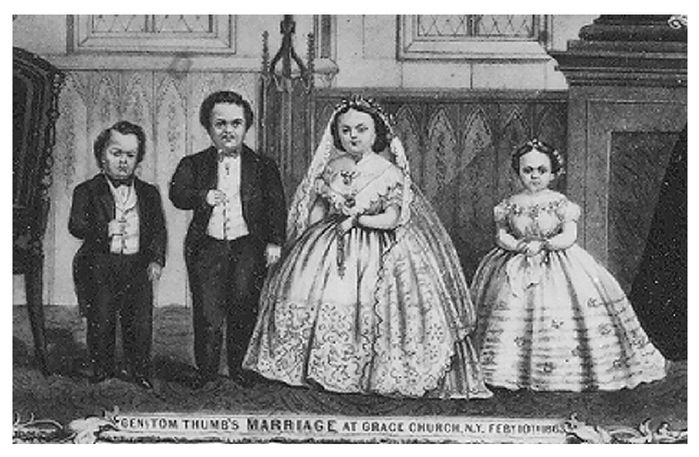

When Barnum found and renamed Charlie Stratton, he invented news. The media loved Tom Thumb. He was the news. When Tom was getting married to the tiny Lavinia, Barnum paid for their wedding. He could afford to. He told the public and the press they better see Tom Thumb and his wife-to-be “Now or Never.” Museum ticket sales shot to an average of $3,000 a day. Barnum offered $15,000 to the tiny couple if they would postpone their wedding. They declined. When the public tried to buy admission into the little ones’ wedding, Barnum declined. He had promised a quiet wedding, and he kept his word. (See

Figure 7.1.) Still, all of these events were news, and Barnum saw to it that the press heard of them.

In the 1860s Barnum again created news by importing zebras, polar bears, camels, sea lions, kangaroos, hippos, and white whales. The world had never seen such a display of nature’s bounty. Because all of this was new and, therefore, news, the public and the media devoured it.

When Barnum wanted to promote the city of Bridgeport, he tested the city’s air with chemically treated paper and then announced that Bridgeport possessed “a higher average rate of ozone than has ever before been found on the face of the earth!” He felt the news would attract health conscious individuals to the city. He was so convinced of his strategy that he made plans to build an Ozone Hotel. This, again, was creating news.

FIGURE 7.1 Tom Thumb’s marriage. (Used by permission, The Barnum Museum, Bridgeport, Connecticut.)

Forget Yourself

Most people in business want to promote their business, and only their business. Although it seems logical, it isn’t wise. Again, you will get far better results if you tie your business to news—even if you have to produce that news.

For example, how would you promote a new play? You might send out a news release. Will that help you sell more tickets?

In 1914 Edward L. Bernays originated news to promote the play, Daddy-Long-Legs, about an orphan and her rescuer. Bernays created a program to encourage private families without children to adopt orphans. It was a brilliant idea. It would help husbands and wives, and it would help homeless kids. Bernays organized Daddy-Long-Legs Groups to help implement the program. The press broadcasted this exciting news nationwide. Every time a story was printed or mentioned, the play was also mentioned. As a result, Daddy-Long-Legs ran for three years, an outstanding success.

P.T. Barnum could have focused his news on the singing talents of Jenny Lind when he promoted her concerts, but he didn’t. Instead, he played on Lind’s very real generosity. He let the press know that Lind donated thousands of dollars to charity, and often gave her entire income from a performance to a worthy cause. This was news, and this news helped promote Lind’s appearances.

Note that Daddy-Long-Legs was just another play until Bernays created some news around it, and note that Jenny Lind was virtually unknown in America until Barnum told the press about her generous soul.

Don’t focus on your business; focus on current news and tie your business to it.

Proactive Success

Phil Morabito learned how to deal with the press while he was a Madison Avenue whiz kid in New York City in the 1980s.

Morabito now runs Pierpont Communications, Inc., a full-service public relations firm. He and his staff handle accounts for individuals as well as Fortune 500 companies. He advises all businesses to run a proactive media campaign.

“Proactive media relations is when you actively send out ideas to media contacts in the hope they’ll run something that plugs you or your business,” Morabito explains.

“You should always be pitching, or presenting, ideas. Send out news releases, feature stories, press kits, letters—everything you can to suggest favorable story ideas. Never stop doing this.”

Another way to be proactive is by letting the media know you are an expert available for interviews.

Although being an author remains one of the best ways to establish yourself as an authority in your field, you can also write to editors and tell them you are an expert. Morabito suggests a letter such as this:

“Dear Editor: I’m John Smith of XYZ Corporation. I’m an expert in (your field). I’d be happy to act as a source on this subject. My promise to you is that I’ll always be available to you, and I will quickly and accurately answer all your questions.”

And what do you do once you’re on the phone with the press?

“Give them whatever they want—and more,” Morabito advises.

“Answer their questions. Offer other ideas, sources, leads, or materials. And follow up to see if they got what they wanted. The people who help the press the most often get featured in the story.”

Barnum would agree. He would go out of his way to befriend newspaper editors and feed them stories. He knew he was helping his business when he helped the media.

How Ink Can Make You Rich

Barnum wrote numerous articles and stories for the press throughout the decades to promote his various curiosities. He knew this ring of power could make him wealthy. He said, “Printer’s ink can make any man rich.”

He knew having and creating news was one thing, informing the press was quite another. He often spent entire mornings writing to press contacts. He kept a secret address book with their names and addresses. He even highlighted the names of those who were most open to news from him.

Barnum also wrote numerous letters to editors, some under his own name, many under fictional names, to draw attention to his business enterprises. The 1800s were a time of invention, and people were curious.When a newly invented machine that could talk was getting attention in the news, Barnum wrote an anonymous letter saying Joice Heth wasn’t a person at all but an automaton, a machine. The media swallowed it and printed it. The public again lined up to see Heth, to try and detect if she was indeed a machine. Again, Barnum tied his story to current news by writing a relevant letter to get publicity. The double whammy worked. Crowds increased in size to see Joice Heth.

Barnum was not bashful about visiting editors of newspapers or even royalty. When he wanted to introduce Tom Thumb to the press, he went right to the homes of editors, knocked on their doors, and placed Tom on their dinner tables beside their food.

In 1872 Barnum hired three full-time press agents to travel with his circus and place stories in the local newspapers. Later he hired seven agents and created a huge, colorful railroad car advertising coach that would visit each city one week before the show was to arrive. The agents would paper the city with flyers and flood the newspaper editors with stories. The result was massive publicity and sold-out events.

Don’t think this is unusual. The media so badly want news that they will often pay for it. The legendary Charles Lindbergh, before flying to France in his Spirit of St. Louis, made a deal with the New York Times that he would get paid to give them his exclusive story. So, in 1927, the famous newspaper paid Lindbergh for the exclusive rights to run his story. When the pilot landed, he called a Times reporter and gave them the news. It was a win-win for all, and in this case Lindbergh even got paid. The Times ran several pages on his flight. When he returned home, he was not only famous, he was a phenomenon.

If you want an even more recent example of how the media loves a good story, consider the case of celebrity magician David Blaine. According to the book It! by Paula Froelich, public relations agent Dan Klores saw Blaine perform, was impressed, and brought him right into the editorial offices of New York magazine. Blaine performed card tricks for the group. Everyone was impressed. New York magazine ran the first feature on the then-unknown magician. That was followed by articles in the New York Post and Daily News. Blaine then picked up the pace on his own by Barnumizing himself with wild stunts, such as spending two days packed in ice in Times Square.

Barnum would have loved it.

Britney Spears Helps Me

In 2004 I began an international marketing campaign to sell my new home-study course, Hypnotic Selling Secrets. The strategy was to hold a teleseminar training where people could listen to me teach them how to use hypnosis in their marketing. At the end of the call, I would promote the course. Obviously, it was imperative that I get a crowd on that call.

I was wondering how I would do it when I saw a commercial on television. It was pop star Britney Spears promoting the perfume Curious. A light bulb went on over my head. I ran upstairs, and wrote the headline to a news release: “Britney Spears Accused of Using Hypnotic Methods in New TV Commercial.”

I then wrote the rest of the release, quoting myself (because I’m a hypnotherapist and a marketing expert), and saying that if anyone wanted to learn more about hypnotic selling, they should attend my call and visit my site at

www.HypnoticMarketingStrategy.com.

I sent out the news release and was astonished at the results. I knew having the sex kitten’s name in the headline would grab attention; I knew talking about a commercial that was airing was current news; and I knew the headline was, well, curious. However, I didn’t know over 35,000 people would sign up for the teleseminar. I made a half million dollars virtually overnight from the sales of my course.

All it took was thinking like P.T. Barnum.

News Releases Lead to Fame

When the first edition of this very book, the one you are reading, was published, I sent out a news release asking, “Are P.T. Barnum’s Methods to Success Valid Today?” I got a few invitations to do radio shows, and a newspaper wrote a story on me and the book, but nothing much seemed to happen.

Until the bomb exploded.

One night a few months later I started receiving calls, e-mails, and faxes, all congratulating me. On what? I had no idea. The next morning I found out that A&E, the national television network, aired a new biography on Barnum. At the end of it the host held up one book and only one book, saying, “Are P.T. Barnum’s methods to success valid today? According to Joe Vitale, author of the book, There’s a Customer Born Every Minute, they are.”

My one-page news release had turned into an ad on national television. As a result, the first edition of this book sold out literally overnight. Book stores couldn’t keep the book in stock, and the publisher was stunned.

You never know when a news release will bring fruit, but when it does, fame and fortune can be the happy result.

Three Steps to Publicity

“But who decides what becomes the news of the day?” one of my clients asked me one day. He runs an enterprise creating videos for businesses.

“What do you mean?”

“At work yesterday a co-worker asked me if I had heard that they were releasing George Lucas’s Star Wars trilogy on the big screen. I told him I hadn’t heard anything about it. Later, I went to my car, turned on the radio, and some announcer was talking about the Star Wars movies coming out. Then, I went to a store and there was a big sign about the Star Wars movies. Who made all of that happen? Who orchestrated that? Who made it the news of the day?”

“The publicity and advertising people working for George Lucas,” I answered. “And then editors in the media decided if it was news.”

“But how can people like me do the same thing in business?,” he asked. “We aren’t all like George Lucas or P.T. Barnum.”

“There are three steps to getting publicity,” I began.

“First, you have to have news. One of the easiest ways to do this is to simply read the headlines in the newspaper and then connect your business to something happening in the news. Retail stores will often have a President’s Day sale right when the President’s Day holiday is coming around. The holiday is news. The sale is associating your business with that news. However, with a little imagination, you can tie your business to anything happening in the news.”

“Give me an example.”

“If cold weather freezes pipes and you are a plumber, you might issue a news release advising people how to protect their pipes in the winter.”

“But I’m not a plumber.”

“I know you’re not,” I replied. “You have to think like a reporter and you have to think of the public, not yourself. So if you’re in a state that wants to pass a new law about increasing property taxes, and you’re a tax attorney, you might issue a news release that stems from the news surrounding the new law.”

“I still don’t get it.”

“Go get a newspaper,” I said.

He got up, looked around, and found a newspaper. He handed it to me.

“No, you look at it,” I said. “What are the headlines?”

“There’s one here about the Internet and how senior citizens are going online.”

“Okay.Your job would be to think of a way to tie your business to that news.”

“You mean maybe writing a news release about how people will soon see television programs and video documentaries on their computer? Or maybe about how senior citizens are putting home movies on computer disks?”

“That’s the idea!” I said.“Tie what you do to current news in an interesting way.”

“What’s the second step, then?”

“Second, you have to saturate the media. Mail, fax, and e-mail news releases about your news. Barnum personally visited the media in his day. Today you can sit in front of your computer and send out news releases over the Internet, but nothing beats personal contacts. Good publicity people get results because they have networked—another ring of power, you remember—and already know who to contact.

“Third, you have to hope that your news connects with the public’s readiness to hear it.”

“What does that mean?” he asked.

“The world was ready to meet a Tom Thumb in the 1840s,” I answered. “I’m not so sure a Tom Thumb would interest anyone today. The public has different interests. If the public isn’t ready to hear about something, nothing you do will succeed. Barnum tried to promote a fire extinguisher in the middle 1800s and everyone thought it was a joke. The invention worked, but people weren’t ready for it. Barnum’s publicity for it failed.”

“It did?”

“Yes. And in the 1830s when Cyrus Hall McCormick demonstrated his new machine—a reaper that was destined to transform farming—skeptical farmers thought it was a humbug. The reaper could do the work of six men, and do it in less time, but the public simply wasn’t ready to accept it until around 1860.”

“So there are no guarantees?”

“No,” I answered. “But if you follow all three steps, you increase your likelihood of success. And if what you are doing connects, your success could be on the level of a George Lucas or P.T. Barnum.”

How Barnum Turned Blackmail into Gold

One day a woman walked into Barnum’s museum office and handed him an article she had written. Barnum thumbed through it and saw that she had written some frightful things about him. Being a man not easily bulldozed by anyone, he handed it back to her.

The woman said he didn’t understand, that she planned to publish and distribute the booklet, and wanted Barnum to buy the copyright to the booklet to prevent her plan from going into action. Barnum nodded, reached into his pocket, and handed her some loose change.

The woman, now shocked by Barnum’s cool manner, insisted that Barnum buy her writing or else. Barnum fairly roared with laughter and then said:

My dear madam, you may say what you please about me or about my Museum; you may print a hundred thousand copies of a pamphlet stating that I stole the communion service, after the Tom Thumb wedding, from the Grace Church altar, or anything else you choose to write. Only have the kindness to say something about me, and then come to me and I will properly estimate the money value of your services to me as an advertising agent.

As far as Barnum was concerned, any publicity would help promote his business.

How President Bush Was Nearly Captured and Eaten

In January of 1997 my friend Dan Poynter, author of Parachuting: The Sky-diver’s Handbook, volunteered to run the International Parachute Symposium for the Parachuting Industry Association, to be held in Houston the next month. More than 800 people from 30 countries were expected to attend. Dan called me for help in promoting the event. Because I was busy finishing the book you now hold in your hands, I told him to contact a publicist I had been teaching, Linda Credeur, and I said I would help her with anything she needed.What Dan didn’t know is that I had already tutored Linda in Project Phineas, my new sales training program based on Barnum’s rings of powers.

Dan was about to get Barnumized.

Dan and Linda talked about ways to promote the event, from sending out news releases to calling the media by phone. Linda—remember that she had already studied Barnum’s rings of power—knew they needed something bigger. They needed to think like P.T. Barnum and come up with a truly colossal idea. They needed a Jumbo of some sort to draw media attention to the event.

Sometimes the answer sits right in front of our noses. One night Dan told the riveting story of how former U.S. President George Bush had been nearly killed when he had to jump out of his crippled torpedo bomber in 1944, during World War II. Bush had to trust his parachute to save his life and to save him from falling into the hands of a sadistic Japanese commander known for torturing captured allied servicemen, cutting them up, and feeding them to his troops. Despite the odds, and thanks to Bush’s parachute, he survived.

Linda recognized a media opportunity. She suggested they create an award for Bush being the only U.S. president to ever parachute and present it to him at the parachuting convention. It was a very Barnum-like idea, but Dan, like most people in business, is a conservative guy. He wanted to send out news releases and play it safe. That’s how most publicists would promote any event. However, if you intend to create an empire, you have to go for the gusto.You have to take risks. Linda was willing. Dan was hesitant. Linda called me to discuss the idea.

“Dan thinks George Bush might want a lot of money to appear,” Linda said. “After all, Bush gets $50,000 to give a speech.”

“But you aren’t asking Bush to give a speech,” I explained. “You’re asking him to show up and accept an award. If he’s at all interested, he’ll do that for free.”

Linda understood that when you appeal to anyone’s vanity, they will listen and reasonably do what you suggest. She agreed that Bush would probably attend the ceremonies. She started asking around and quickly found the name of Bush’s former White House publicist. Linda sent a message to Bush, through the publicist, explaining the award and their offer to present it to him at the opening of the parachuting symposium. What no one knew was that Bush had a presidential library stocked with valuables—including a Navy torpedo bomber—and wanted a 1944 parachute to complete his collection. Bush said he would attend the event if someone could locate a parachute like the one he used during World War II.

Dan’s an expert on parachuting. He found the rare parachute and Bush agreed to the awards ceremony. On the morning of February 10, 1997, a gracious and humorous George Bush appeared before the media to accept his award, the 1944 parachute, and to inadvertently publicize the 1997 International Symposium. Five news crews covered the event. CNN gave it national exposure. The local papers saturated the city with the news.

“You took an ordinary industry gathering,” Dan later wrote Linda, “and turned it into a major media event.”

In short, getting a former president of the United States to attend the convention put the entire event on the map. The media ate it up. The public liked it. The convention attendees, who had never seen anything like this before and for a few seconds couldn’t believe their eyes, experienced an exciting kick-off to their convention, and none of it cost a dime.

What it took was thinking like P.T. Barnum.

“I really owe you one,” Dan Poynter told me by phone three days after the event.

“You don’t owe me,” I replied. “You owe Linda Credeur and P.T. Barnum.”

Offer the media news about your business because they want—even desperately need—to hear from you.

“Academicians who study media now estimate that about 40 percent of all ‘news’ flows virtually unedited from the public relations offices,” writes journalist Mark Dowie in the introduction to Toxic Sludge Is Good for You!

My own study reveals that up to 80 percent of what you read in the papers was planted by people who sent out news releases seeking publicity. Bob Bly, in his excellent Targeted Public Relations, cites a Columbia Journalism Review survey of the Wall Street Journal where they found that more than one hundred stories on the paper’s inside pages were taken directly from press releases.

Consider that there are 150,000 well-paid public relations professionals in America versus 130,000 underpaid reporters and you get a sense of how reporters rely on news releases to get their information. Aaron Cushman, famous publicity master, says there is no way a major city can find all the news because they simply don’t have enough reporters. Help the press and they will help you.

What can you do right now to give the media news while promoting your business?