TEN

SOMEDAY WE’LL ALL BE FREE

The point of this whole thing isn’t just to fight White supremacy; it’s to destroy it and create something that is liberatory for all. But we can’t accomplish this without having a vision of what our own liberation looks like. That’s why we all need to document our freedom dreams. Our picture of a place without police brutality, mass incarceration, grinding poverty, mass unemployment, untreated mental illness, early death, substandard education, gun violence, hate violence against Black trans women, homophobia, and sexism, must come from folks across the spectrum. In this chapter, we hear from futurists, survivalists, trans rights activists, and more about what they do each day to free themselves and how we can sprint toward a just future. Together.

Start with Quanshay

Imani Perry

I can tell you how we fight. I can’t tell you how we win. That’s probably obvious. If I knew, if we knew, the whole thing would be different. The long nightmare would be over, and we would be in the middle of the next epoch of our collective being. Maybe that would be like Wakanda, or the Republic of New Afrika, or Atlantis, or a great big neo-Atlanta. Who knows? We’re here, though. And we can fight. We do fight. And knowing how to fight, I think, is identifying the necessary. It is about hitting the right note with our state of being even when the piano is out of tune. Even when we want to throw the damn thing out the window and let it crash into a million splinters on the concrete.

The world knows, but it denies, that Black people love being Black. Of course, I don’t mean every single Black person loves being Black. We can think of some very prominent exceptions to that rule who have surnames like Dash, Thomas, and Carson. But it’s true. Loving being Black is a commonplace state for Black folks, even in this White supremacist country in a White supremacist world. Sit in a room with Black folks for a day, or even just a few hours, or for fifteen minutes on a street corner, and the fact is undeniable. We love the heft of our laughter. We love the swing of our voices and the timing of our bodies, the subtlety of our eyebrow gestures and glances, the thickness of our own embraces. We love our mastery of combinations and permutations—the mathematics of our entertainment—with cards, dice, stories, and dance. We love the way we praise the higher power, however we call her. We love the knot of our genealogical ways of being that allow us to slip in and out of each other’s neighborhoods and nations and find a way in wherever we go because we know the language even if we don’t know the language. My friend Nate once said to me, “It’s a myth that we can’t go back to Africa. Start telling jokes with the kids in the village and you’re back in a minute.” He’s right. We don’t have a Standard English term for this, but we know that robust good feeling of being inside of being with other Black people.

Despite this truth, we are forced to listen to a steady parade of well-paid commentary about how we don’t love being Black. It goes like this: “I wanted to be White. I hated myself. I changed my voice. I wasn’t like the other Black kids.” On and on and on. “There!” I imagine some collective White supremacist personality (or publisher) saying. “I fixed it. We have told them they are inferior and they believe it. Told you!” Ridiculous. Okay, I admit that some of us believe this pernicious lie. But most of us know in our guts that it isn’t true. We are definitely not inferior. We are in fact remarkable and breathtakingly beautiful. And what a marvelous resilience that is. Really.

As far as I am concerned, knowing it is good to be Black even when it is terrible to be Black is at the core of how we fight. Start from there and Bob Marley’s “emancipate yourself from mental slavery” and the Funkadelics’ “free your mind and your ass will follow”—those one-sentence sermons—have a chance to come true.

Black names, from African to African American vintage, are a good example. We like the sounds of a hard k and a kwa and a sh. We like -ay at the end. And for some reason we like to borrow the flourishes of French at the same time as we keep the rounded sounds of Bantu languages. Our names are a common source of mockery, sometimes even from our own. Well, it is true: We like to make up names from an old grammar of sounds that came before Columbus. And just think about what it means to celebrate sounds of our own, to claim them as the banners of our identities. It is a defiant deed in a White supremacist society.

No matter what they say, we aren’t naming our daughters “Susie.”

So whenever someone makes fun of Black “made-up names,” I remind them that Milton made up the name Susannah. And I ask, “Do you mean to say that only White men are allowed to make things up?” They usually get uncomfortable. But I am very serious. The Black imagination is essential for the road to freedom.

When I was seven years old, I told my teacher that the map of Africa in our classroom was wrong. It said Rhodesia, but the Black people had reclaimed that country as Zimbabwe. I had been taught that renaming was decolonial. To her credit, my teacher, Risa (it was a progressive school; we called them by their first names), took a piece of tape and wrote Zimbabwe over where Rhodesia had been. Like many other African-named children of the 1970s, I was raised to reject the colonized mind. Steve Biko’s lessons in Black consciousness had been put into practice as the enterprise of parenting.

I like to think I have carried that on. I tell my children when they learn in school to call European expansionism “The Age of Exploration” to remember that it was the age of unjust conquest. I like to think that when my younger son is tasked with doing a language project and he chooses African American Vernacular English, and when my older son says the foreign language that he is most interested in learning is Jamaican Patois, that this is part of the work of emancipation—this is the work of freedom-fighting.

The point, I hope, is clear. But in case it isn’t, I will be more explicit: the boldness of our laughter comes from the same fabric as insisting upon other ways of knowing, ways that weren’t built on the altar of our degradation and subjugation. It is of the same fabric as having vocabularies and designations of our own design. To tell our story truthfully is to turn the official story on its head again and again, based on the core principle of loving who we are.

To get from there to here, however, from the rough act of self-love to a deliberate way of being, is community work. We have models for it. We have books and a history of schools and organizations. There is a lot to draw upon. The problem, however, is so often when we embark upon that work we start from a place of denigration of what is. We repeat the core formulations of White supremacism with “the problem is that Black people…” as a precursor to “where do we go from here?”

But what if, instead, we begin with “the beauty is that Black people…”? What if we begin the story of our greatness and our possibilities with where we are and what we love about ourselves right now? What if we see in the grammar of our dances a thousand permutations on grace under pressure. What if we see a refusal to be held captive in the timbre and echo of our voices, which carry even when we are held in cages, or behind invisible electrified fences of ghettoization, or under leaden glass ceilings. I believe that is how we must fight.

Start right here.

Imani Perry is the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, where she is also affiliated with the Program in Law and Public Affairs, the University Center for Human Values, and jazz studies. She is the author of several books, including May We Forever Stand: A History of the Black National Anthem. She lives in the Philadelphia area with her two sons.

I fight White supremacy by understanding its nuances. Most racism and oppression isn’t overt; but by pointing out racism at its subtle level to my sons, I equip them to avoid and beat covert White supremacy.

—A. Jermaine Mobley, songwriter and composer

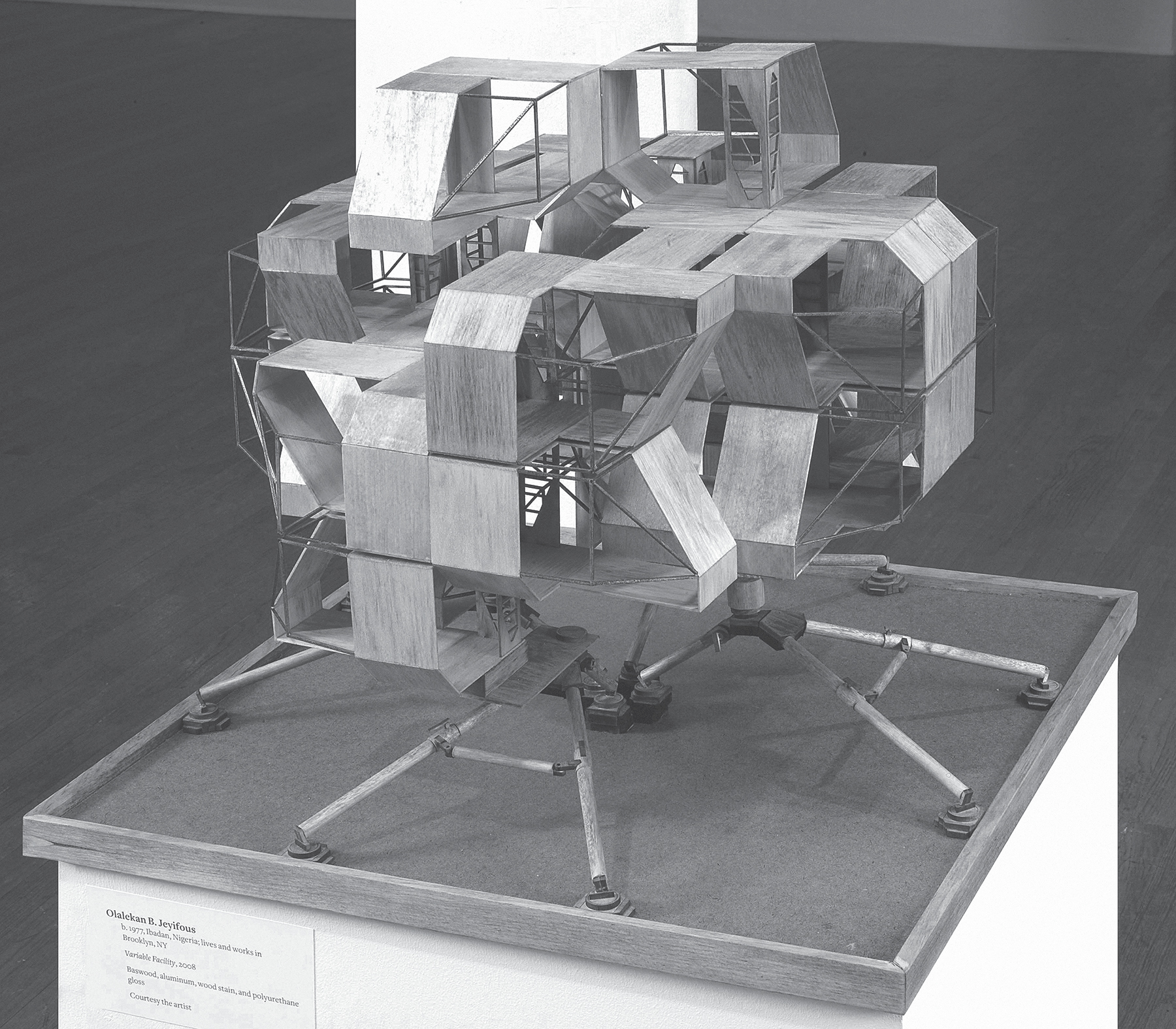

What were you thinking when you planned and created this work?

I was thinking about creating a modular, mobile, and elevated housing construct driven by an experimental yet organic design and sited within a repressive political economy.

How does this work resist White supremacy?

A good deal of my artwork that derives from my background in architecture is about resisting or confronting White supremacy in some form or other. In this case, it’s the very act of imagining spaces for Black people in the future. In the present, urban development often fails to adequately consider the needs of marginalized communities. This piece is an act of resistance against erasure and a history of discriminatory housing practices.

Olalekan Jeyifous is a Nigerian-born, Brooklyn-based artist and designer. He earned a bachelor’s degree in architecture from Cornell University, where he focused on experimenting with the application of various types of computer software in the creation of art, design, and architecture. Since then, he has served as a senior designer at dbox, exhibited his artwork in venues throughout the world, and created visuals for a variety of clients.

What Freedom Feels Like

Maori Karmael Holmes

What I’m interested in for Black people in the United States is that we would be free to have a mundane life. To wake up, to go to the store, to shop, to see our lovers, to come home, to watch television—all without considering the White gaze. And not watching somebody grab their purse in the elevator, or dealing with microaggressions at work, or skipping the major you love because a racist counselor said, “You can’t.”

I don’t think freedom would look the same for everybody; I’m actually more curious about what it would feel like. It would hinge on being able to make decisions that aren’t based on a legacy of trauma or impoverishment. We would no longer have to choose how we take up space—or don’t take up space—as a response to this world, even down to the clothes we wear. For example, when I see free White people, particularly the wealthy people I’ve met, I notice how they’re free to wear the same clothes every day. They don’t dress up if they don’t feel like it; they dress up if they want to. Either way, they’re making these decisions purely based on their own interest. To me, that’s what freedom would feel like.

Maori Karmael Holmes is the founder of the BlackStar Film Festival.

The Eight-Point Plan of Euphorically Utopic World-Making

Elissa Blount Moorhead

My father took me to see Miles Davis a few times growing up. What struck me most was his now-infamous tendency to play music with his back to the audience. Some say it was not a deliberate act of defiance, but rather a deep focus on his work and his stagemates. Maybe he would’ve said, “My back was not to the audience; I was facing my band.” Regardless of his reason, to my young eyes it was a gesture that resonated as a manifesto for so many aspects of life. It called out to me: “Don’t look over your shoulder. Let the world come find you—you don’t have to go to it. When they do find you, be totally into and enjoying your own bag.”

In other words, I haven’t really given Whiteness my back. I am facing Blackness.

I’ve had a few bags throughout my life—career, crews, cities—but the bag for which I have always had an unwavering love is Blackness. I never tire of pondering who we are and what we do. I suspect it has to do with what I am retroactively calling the “Eight-Point Plan of Euphorically Utopic World-Making.”

This is the plan that my counterculture parents created. Their insistence on world-making shaped our current existence and our understanding of it—specifically, their experiments in child-rearing. I was taught to decentralize any notion of the White gaze, which means I had a fighting chance at agency, self-worth, and cultural entitlement in a country dead set against us having any of it.

I grew up in Washington, DC, during the time of liberation movements, communes, pan-Africanism, shules, arts movements, Islam, Vodou, and Black political and cultural nationalism. Black folks, including my parents, were searching for alternative ways to live together and raise a new consciousness. They were clear that being raised in an intentional community of Black artists, thinkers, activists, and pioneers was going to give us the grounding we needed to not just avoid the White gaze and misguided ideas of White “supremacy” but to utterly ignore its existence. Don’t get me wrong. There were inconsistencies. They were jumping off cliffs and building wings on the way down. Most parents are really figuring it all out in real time.

Even though the world at that time was trying to convince them racial integration was salvation, they knew that was not enough. A half-century before “Black Lives Matter” was a mantra, they bet on Black and, in my opinion, won.

Some of these memories started to congeal when I had my first child. I began to recall these stories under loose categories that protected me (as much as possible) from White “supremacy” during my formative years.

1. Squad

When I was young, I never understood why people of color were called “minorities” when we comprised the majority of the world. Of course, later I came to understand this Western fiction was a tactic to advance the idea of Whiteness. It was a numbers game and a proximity mind trick. Whiteness was a catchy recruiting tool that allowed anyone throughout history wishing to distance themselves from Blackness to promote my inferiority.

But DC in the 1970s and ’80s looked more like the rest of the globe. This was nearly an all-Black city—residents, leadership, services, and commerce. It’s home to Howard University, nicknamed “the Mecca,” which is what drew my parents there. Growing up in DC made it easy for me to take this fact of our majority status for granted.

Once, after college, a Black friend from London came to visit for the first time. I was amused by the first places he wanted to visit. “Where can we get bean pies?” he asked. “Let’s go to Howard and where are the go-gos?” After a day of fairly mundane hanging in the city, he said, “My God, everyone is beautiful! The traffic cop, the bank teller, just regular people, are fine.”

His being awestruck made me realize that I had a sense of entitlement that rested, not in the fact that I had Black teachers, leaders, and visual validation, but in my ability to be nonplussed about it. If someone said the phrase “French bakery,” my mind’s eye went to Avignon Frère, where Francophone Africans would hang out. When I imagined a pediatrician, she would be kind-faced, brown Dr. Clark on Sherman Avenue.

Numbers mattered when I was formulating identity. Because I had numbers, I didn’t have to count. There was a deep-down “they can’t kill us all” kind of safety, to assume the whole world looked and lived like me.

2. Isolation

Doing away with America’s “separate and unequal” brand of segregation was the Civil Rights Movement’s raison d’être. However, since Brown v. Board of Education was decided, some Black people have spoken in hushed tones about the negative effects of desegregation. If you listen closely, you will hear longing for many attributes of segregation. You’ll hear yearnings for the space to elevate spirit via Black sociality and euphoria. That seems essential to me.

So my assumption is that the Black psyche has been impaired or at least affected by the White gaze. Even in all-Black spaces, the specter of the White gaze fuels our perpetual impulse toward doing what is deemed respectable. I came to believe that we could interrupt this impulse with room to try things on and fail without it being attributed to Blackness or lack thereof.

I remember being mildly chided in high school as “punk rock.” At the same time, I was voted “Most Creative.” Today I realize that people calling me “punk rock” was a way of saying that I was into some weird stuff that wasn’t really that Black but did not make me an outcast.

With Whiteness out of the frame, this was, “Lisa who likes weird shit,” but I was not “acting White.” I had no real-life pressure to avoid “Whiteness” because it wasn’t present in my life. In other words, in isolation my behavior and preferences were not raced and categorized in the face of “Whiteness.” I don’t want to confuse this with a post-Black ideology. This is more about transcendence and disregard of White people’s view of us. It’s Black privilege.

3. Multiplicity

Many scholars have written about what it means to remain at the “epicenter” of Blackness. Freedom from a one-dimensional view of Blackness allows for rigorous discourse and more expansive notions of what Blackness does and can mean.

Living in a diverse Black community allowed me a window into our diasporic bounty. Living in a Black community in America means the sinners and the saints all look like you and are potentially connected by history, circumstance, and culture. We see ourselves for intrinsic traits, not a romanticized Blackness.

4. Haughtiness

Segregation or isolation would not have been enough. Expressions of “Black is beautiful” were almost compensatory for what America was dishing out. I’m guessing this is what we needed to level things after church burnings and hoses. But alongside this prideful proclamation was also benevolence—the cousin of haughtiness.

Benevolence is usually reserved for the group of people holding power. But in my near-utopic example, power was a shifted perception. Benevolence allowed for a lack of ire that is not typically associated with a Black Power stance. I remember my mother and grandmother talking about the dysfunctional behavior of our people that we’d hear about on the news. They would say, “Poor thing. He doesn’t know any better. He was taught that.” There may not have been genuine feelings of sympathy, but the performance of superiority resonated with me.

Whiteness, to me, was the condescending pity and its belief that it was above it all. So my grandmother would not answer if a White person called her by her first name or used the wrong tone. Her haughtiness worked as an antidote to White “supremacy.” Disregard as resistance had another side effect: the erasure of the excuse that racism is a “sickness” rather than a learned culture. This was the ultimate high-siddity smackdown.

5. Global Context

When I was young, a five-year-old girl in my building spoke five languages that I knew of, including Amharic and English. When you got on the elevator, she could size you up based on gestures or clothing or style and speak to you in the correct language. I think about how she had so many keys to various kinds of Black thought and culture so early. In our apartment building, there were French/Kreyol speakers from Haiti and West Africa and Spanish speakers from the Dominican Republic and Central America. Not to mention Brazilians, South Africans, and West Indians from at least eight islands. It was a Black United Nations. Before I even traveled out of the United States, I knew I belonged and was not a minority. I knew that Pelé played a game more popular than baseball and that slavery did not take everything away.

6. Chill

When I first went to college at American University, I remember meeting students who claimed to have always been the only Black person in their schools or communities. This sounded heartbreaking.

Folks who are performing Blackness or proving (or disproving) their connection to it all the time carry an unfair burden. Quiet confidence comes from mastery of work and ideas, but also of self.

Last year I dropped off my niece at the hairdresser before her orientation at the Mecca. The hairdresser said, “Congrats! What high school did you graduate from? She said “Friends” (a private Quaker School). The hairdresser said, “What made you choose Howard?” Without taking a breath my niece said, “Friends.”

7. Fun

Once when I was eight or nine, a girl from my second DC school—a middle-class to wealthy Black school—came to my apartment. Seeing all the pictures of Black heroes and African art, she said, “Do your parents lecture you about Black stuff all the time? Do they hate White people?”

Funny enough, they didn’t do either. We just lived. There were always people at our apartment late, smoking weed, listening to records, arguing, and laughing. I loved the residue of it all. We lived in museums and at cultural events. We didn’t know we were technically poor.

My wealthier friends I went to school with had similar fun—basement dances, roller skating, slumber parties where we’d pore over Right On and fight over who was going to marry Michael Jackson or Foster Sylvers. So Blackness always seemed lit to me.

Often, in an attempt to make sure our kids don’t forget who they are, we make things prescriptive and, as one of my friends says, we take the fun out of profundity. We think ceremony and lessons are the only way to get them to know our history. But we are making our history now by loving, laughing, and being ourselves in front of them. Making sure I continue my version of my parents’ fellowshipping is soul-feeding for me, and I hope it will make my kids want to hold on to their uncut joy free of any outside gaze. Full. Out. Lit.

8. Evidence and Expectation

Maybe I never bought the “White man runs the world” story because my near-utopian reality showed me too much to the contrary for too long. For me, there was no evidence of anyone but Dr. Clark and Marion Barry running the world. Really well, I might add. I knew that President Jimmy Carter was White, but his daughter went to public school in DC too, one that was not as good as mine. At my school, we sang “Lift Every Voice and Sing” every morning, so I thought all schools did.

No matter how hard you worked, teachers would say you weren’t working to your potential. That bar was raised hourly. I remember thinking, Well, maybe this is my full potential, lady. Leave me alone. But I soon learned there was no ceiling. Teachers would then say, “This is your best? Please, child, I know your parents.” Which is code for “You come from good stock,” which is code for “We all we got,” which is code for “You must win because you are mine.” Even when naïveté wore off as an adult and I understood the economic realities, injustice, and racism we faced, I still couldn’t buy it. No White man is running my world. Evidence was everywhere.

It was rare, too special, a coincidence of time and place that we will never get back.

My kids’ schools are far from Shepherd or Harriet Tubman Elementary where I went, so I supplement with summer Freedom School—any element of this eight-point plan will have to do for now. I am trying to replicate what I can, when I can. It has to be strong enough to endure racist governments and all-White classrooms. It has to be seen and felt, not implied. There has to be evidence.

Elissa Blount Moorhead, artist and curator, has created film, public art, exhibitions, and cultural programs for the last twenty-five years. She is a principal partner at the film studio TNEG and the author of P Is for Pussy, an illustrated “children’s” book.

We Can’t Get Free by Osmosis: A Q+A with Robin D. G. Kelley

Robin D. G. Kelley is the Distinguished Professor and Gary B. Nash Endowed Chair in US History at the University of California, Los Angeles. Outside of academia, the writer, educator, cultural critic, and activist is renowned for using his dizzyingly multidisciplinary talent to talk about Black culture and politics with clarity and verve. His study of Black working-class social movements—including the books Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class and Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination—is what compelled us to talk to him for this project. Read on as he emails with Akiba.

These words on your website about your 1996 book, Race Rebels, stood out: “I concluded that there is nothing inherently radical or oppositional about daily acts of resistance and survival; the relationship of these acts to power always depends on the context.” Can you talk more about this conclusion?

The key words in that quote are “inherently” and “context.” I don’t want to give the impression that these everyday acts of resistance or survival are not valuable. On the contrary, the whole point of the book is to insist that we cannot understand working-class politics without paying attention to the realm of these everyday, quotidian kinds of struggles.

But to assume that these are conscious acts of rebellion or that they lead inexorably to revolution, the idea that they are proto-revolutionary and whatnot, is simply wrong. It both underestimates and overestimates our communities. What I mean is that we don’t always recognize what a diverse and complicated people we are and how any number of tired terms like “rebel” or “reformist” or “integrationist” or “separatist” obscure more than they reveal. Even under White supremacy, we are not obsessed with this system or White folks or being oppressed. We are sometimes struggling with mundane problems, seeking joy, falling in and out of love, raising children, or more concerned with dignity than, say, protest. We do stupid things, exhibit vanity and selfishness and many other things that some might dismiss as signs of lacking consciousness. But how we come to know the world is usually through a dialectic of experience, knowledge, and reflection on both. This leads me to the second key word: “context.”

A style, a gesture, music, even literacy may be looked upon by authorities as subversive and dangerous in one context, and a marketable commodity in another context. And the threat it may pose for White supremacy may not be evident to those who engage in these acts. In some instances, Black working people acted in ways that were never meant to “resist” anything, but the context—the policing of Black working-class behavior, the monitoring of Black life, the way the state perceived their acts as threats—rendered their actions resistance whether intended or not.

Furthermore, everyday resistance strategies can become double-edged swords. Vicious attacks on Black passengers by bus drivers could convince others of the futility of fighting back. Impeccable job performance as a strategy to challenge racial inequality at the workplace ultimately benefits the employer. Employing one’s own labor for more pleasurable pursuits hardly alters social relations. And yet, like all double-edged swords, these same acts can temporarily disrupt the business of White supremacy by throwing a wrench into its operations, by instilling communities with a sense of dignity denied them by the racial regime, and by enabling folks to reverse the process of exploitation by taking back some of the surplus extracted from them. These things happen every day. The question is, how do we make meaning of these daily acts and skirmishes? And can they become the basis for disrupting the system we’re trying to dismantle?

What do Black folks get out of valuing and even romanticizing everyday struggle? Did it ever make sense?

There is certainly no consensus among Black folks on the value of everyday struggle. Some of my biggest critics have been Black intellectuals who see no value in studying everyday resistance, arguing instead that they are diversions from “real” social movements. On the other hand, I’m surrounded by many students, colleagues, and activists who want to hold up these acts as evidence of Black people’s “agency” or “humanity”—a claim I find incredibly dubious and that was powerfully critiqued recently by Walter Johnson in his October 26, 2016, Boston Review essay, “To Remake the World: Slavery, Racial Capitalism, and Justice.”

I find it dubious because we don’t have to prove that we have agency or have held on to our humanity. If we are human, then that should have never been a question. Moreover, agency does not mean resistance or rebellion—just the capacity to act, for better or for worse. Drug dealers and slave drivers have agency and humanity, especially in light of all the destruction and havoc around the world caused by and in the name of humanity. Of course, there is something edifying about celebrating our resilience and all that business, but that stuff never appealed to me.

I took up the study of everyday struggle to better understand and buttress the social movements with which I was involved. I learned that the most effective social movements develop organically and create agendas around people’s actual needs and grievances, not according to Marxist or liberal logics. I understood the study of these kinds of everyday forms of resistance, survival, renewal, as diagnostic, intended as a measure of power relations and a way to gauge the grievances of working people who might not have other avenues through which to voice their concerns. The state’s reactions to everyday struggles also tell us something about the workings of power, and that is precisely the kind of knowledge we need to create better strategies to contest White supremacy.

Do you see yourself as fighting White supremacy? If so, how do you do it?

Yes. For the last thirty-five years, I have tried to fight White supremacy through my writing and speaking, in the various organizations I have supported over the years, from the Black Radical Congress and the Labor/Community Strategy Center to the Movement for Black Lives and beyond. But we need to be clear that removing all racial barriers, vigilantly upholding antidiscrimination law, incorporating us into the system, and replacing White authority with Black and Brown faces is not the same as dismantling White supremacy. We should know by now that the state and the dominant class have no problems granting Black people and other aggrieved “minorities” recognition and incorporating them into the existing state apparatus. We’ve watched this happen over the course of the last four decades, at least, resulting in Black CEOs like Franklin Raines contributing mightily to the financial crisis of 2008; a Black president, a Black secretary of state, and Black national security advisers who advance the US war aims in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and virtually everywhere on the planet; the right to same-sex marriage based on the same principles of marriage as a property relation; and the right of people of color, women, and queer people to kill and torture around the world.

And at least in my worldview, dismantling White supremacy is not enough; liberation requires a lot more. As the Combahee River Collective Statement, now four decades old, made crystal clear, we cannot wage an assault on White supremacy without fighting to end patriarchy and capitalism—its fetishism of commodities, its law of private property, its gendered logics, bourgeois individualism, its culture, its state apparatus. I know it is in vogue now to call racism “anti-Blackness” and to embrace a politics that forecloses the possibility of cross-racial and international solidarity, but I’m committed to resisting all forms of oppression, not just anti-Black racism. I really identify with those women of the Congress of Afrikan People in the late 1970s whose slogan—which they took from Lenin’s essay “Soviet Power and the Status of Women” (1919)—called for “the abolition of every possibility of oppression and exploitation.”

I Fight White Supremacy by Being Apocalypse-Ready

Mia Birdsong

When I was pregnant with my first child, my husband and I moved from the Bay Area to the Round House—a beautiful, funky home on forty acres off a dirt road in California’s Central Valley. It’s the house where my husband was born, and living there meant our cost of living was low enough for us to both stay home with our new kid. Surrounded by little more than oak trees and cow pastures, I discovered that I am a city girl. But I also discovered the satisfaction of living a less convenient life, one that requires and inspires learning some basic self-sufficiency skills.

There is this thing that happens to some of us when we become parents: we become paranoid as fuck. We worry about freak accidents injuring or killing our kid, we worry about our own mortality. We start planning for the worst. This is, of course, compounded when you are Black. While I never had any indication that there were violent White supremacists anywhere near us, being so far away from civilization freaked me out. Out in the country, no one can hear you scream.

Shortly after our daughter was born, my husband, a musician, started touring frequently. Every night he was gone, I would lie awake until I had thought through what I’d do if the White supremacists came for us. I’d probably hear them come up the driveway. They’d get in the house easily, because there were no locks on the doors, but the dogs slept downstairs and would keep them occupied long enough for me to strap my baby into the sling and climb over the second-floor balcony. I would have to escape through the woods, because the White supremacists would be blocking the driveway with their trucks.

But country living and parenting didn’t just feed my fear. It also fed my sense of freedom. I gardened in earnest for the first time, growing inedible zucchini the size of my arm and hundreds of tomatoes that never ripened. Those early mistakes taught me as much as my successes. I learned that paying attention reveals what my garden needs and when it needs it. I learned that sometimes a little hardship creates studier plants, and that sometimes you need to cut back to encourage growth.

During the two years we lived there, I apprenticed with my mother-in-love, a brilliant midwife. Accompanying her to prenatal visits and births was mind-blowing. I had read midwifery books, but observing and supporting a master showed me the depths of knowledge and artistry it takes to guide, but not disrupt, a process that has a wide range of normal and deeply connects us to our animal selves. Most importantly, it reminded me that we are built for life. My brief apprenticeship did not make me a midwife, but in an emergency, during the apocalypse, I could catch a baby.

During our country-living years, most days I spent hours walking the land with my infant strapped to me, talking to her about the trees and birds. The landscape was foreign to me, which made me both uncomfortable and curious. I learned the names of the creatures and plants. Live oak, fly catcher, ceanothus, California newt. In the morning, from our bedroom window, I watched deer graze in the orchard. At dusk, I heard coyotes carry on and saw bats catch insects. I became aware of the rhythms of the natural world and realized that it was something I was a part of, not separate from. And if I was part of it—if it was my habitat too—then I could survive in it.

In the summer, klamath weed, a pretty yellow-flowered plant, bloomed in abundance. My mother-in-love told me it was also known as St. John’s Wort, a plant I knew from the bouts of seasonal depression I experienced in college. It had kept me from spiraling into the abyss during long Ohio winters, and here it grew like a literal weed that I could harvest. I’d started studying herbalism several years before, but this encounter shifted my relationship to plants. I could make medicine. I remember thinking that if the apocalypse came, I could help out with all the anxiety, panic, and depression that would accompany it.

Since moving back to Oakland, my husband and I regularly talk about who we’d circle up with, what we’d take with us, and how we’d get out if society fell apart. I recently took up archery with my second child, in part because it’s fun, but also because during the apocalypse, when all the bullets are gone, we still have to defend ourselves and eat.

I have maintained the curiosity that inspires me to know how to do things that support collective self-sufficiency. In our little backyard, I grow food and medicinal herbs. I took up beekeeping after a swarm of the honey producers landed in our yard on my birthday a few years ago. I care for a flock of six chickens.

Home invasion preparation and escape planning came from a place of fear. Gardening, beekeeping, midwifery, and my nascent archery practice are all practical skills that I can tap when the crisis is over and we need to rebuild. But they also keep me fully living now. When I’m pulling frames full of honey out of a hive or loosing an arrow, I must be totally present. Planting seedlings and sitting with a laboring pregnant person invites a kind of in-touchness that deepens my ability to be alert and aware of the rhythms of my surroundings. That’s good in an emergency and for long-term staying alive—now and post-apocalypse.

Knowing that I have skills to bring to our survival when shit goes down gives me a sense of security when my news feed is full of Black death and so many of us are struggling to make ends meet and stay healthy.

I went into fall of 2015 feeling heavy. So many Black women in my orbit had recently died, were dying, or had been diagnosed with a chronic illness. Living at the intersection of patriarchy and White supremacy is traumatic.

Into that grieving walked Nwamaka Agbo, a restorative economics practitioner, at a retreat the Movement Strategy Center held in Oakland. During a break, she and I walked around Lake Merritt and we talked about the ways we saw the double-edged sword of Black women’s strengths, ingenuity, brilliance, and excellence result not just in achievement and survival, but illness, disease, trauma, and death. All the exceptionalism, doing it ourselves if we want it done and making a way out of no way, came at a cost.

We also recognized that we, and the amazing Black women we knew, were helping White supremacy and patriarchy out by not caring for ourselves enough, by not dealing with our historical and lived trauma, by not examining deeply enough the ways in which we internalize racism and sexism.

We shouldn’t have to do all that work. But in this too, no one is coming to save us. We knew we wanted to create a solution that would help heal us, and we wanted to start from a place of joy, with our eyes on freedom, because while it is key, healing is not the end goal—liberation is. It took us almost a year to start (because it is challenging for Black women to prioritize ourselves), but that conversation birthed Black Women’s Freedom Circle. On a sunny day in August, twenty-plus Black women met at my house for three hours to nourish our bodies and spirits, to connect with and witness each other.

We each identified a time or practice that made us feel free. We discussed what that feeling was and how we could expand it beyond the moment we’d identified. We agreed that the exploration of freedom was imperative not only to our own personal well-being but to our collective emancipation.

Like most people, I imagine the apocalypse as a disaster (nuclear war, earthquake, environmental catastrophe, government collapse, zombies). My mind is full of all the dystopian possibilities I’ve absorbed from science fiction TV, movies, and books. And in a world that hates Black women, where the state is not designed to care for or protect us, I feel some imperative to be able to care for and protect myself and my loved ones. But I also understand the apocalypse as an opportunity for renewal. A world shaken off its foundation can be built differently, better. But we have to hold a vision of what future we really want so as not to re-create the messes we have now. As Lucille Clifton made clear, “We cannot create what we can’t imagine.” Freedom from oppression is not a linear path we travel toward the future. It is something that has to exist inside each of us—a moment that we can repeat, a spark we can fan into fire.

Black Women’s Freedom Circle has been gathering regularly since we started. We have talked about anger, grief, safety, family, intimacy, and purpose. We laugh and weep and hold expansive space for all our feelings and experiences. We do witchy shit and research internet security. We circle up to make real the world we want to live in.

This too is being apocalypse-ready.

Mia Birdsong is a pathfinder, community curator, and storyteller who engages the leadership and wisdom of people experiencing injustice to chart new visions of American life via her New America public dialogue series, which centers Black women as agents of change.

Blak Kingz

A song by Jasiri X

I had a dream I met Lebron James

We were speaking on Black empowerment

Sending money to a Black bank call it power trip

If it ain’t Harriet on my twenty that shit’s counterfeit

Black faces in my denim lining

Tailor-made stitching like we ’bout to win the Heisman

Call my brother Sun ’cause I love it when he’s shining

The pressure made me precious my flesh is a living diamond

We buying back the hood and consolidating wallets

A principle of Kwanzaa cooperative economics

Raid Wall Street and put the stock up in my pockets

My checkbook is like the Bible, its full of Black prophets

Satan in my rear view

The devil whispering but I don’t hear dude

Earbuds for the bullshit I gotta steer through

Freeze everything and run away that’s what fear do

It’s hard to stay asleep when your dreams are so near you

I gotta dream

All white furs for the team

I gotta dream

Diamond chains, watches and the rings

I gotta dream

Counting my money with a machine

I gotta dream

Bow down to a Blak King

I had a dream I was talking to Chance

Seen him in the street and then offered my hand

Not for the ’gram or all of the fans

’Cause even though we write verses God authors the plans

The most merciful

Please make my life purposeful

Make me an example to those who still worship you

Make me like water for those who may have deserted you

And please forgive all my curses too

And all the times I wasn’t present in that church’s pew

Reverend I got work to do

Heaven and an earth to move

Judge me with your surface view

I don’t take it personal

My coat is reversible

Bursting through the birth canal

Lord, I was an earnest child

But I promised if you gave me light that I would burn it down

You admonished if you gave me sight to never turn around

Word is bound

’Cause every real king gotta earn the crown

I gotta dream

All white furs for the team

I gotta dream

Diamond chains, watches and the rings

I gotta dream

Counting my money with a machine

I gotta dream

Bow down to a Blak King

’Cause they don’t wanna see Blak joy

Do your dance Blak girl do your thing Blak boy

’Cause they don’t wanna see Blak joy

Do your thing Blak girl do your dance Blak boy

Jasiri X is the first independent hip-hop artist to be awarded an honorary doctorate, which he received from Chicago Theological Seminary in 2016. Still, he remains rooted in the Pittsburgh-based organization he founded, 1Hood Media, which teaches youth of color how to analyze and create media for themselves. Jasiri received the Nathan Cummings Foundation Fellowship to start the 1Hood Artivist Academy, and he is a recipient of the USA Cummings Fellowship in Music and the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Artist as Activist Fellowship.

I fight White supremacy by hiring directors and producers of color in an industry where they might not otherwise get the opportunity.

—Gideon Moncrieffe, live event and media production executive

On Restoring Our Humanity in a World That Wishes Us Dead

Wazi Maret

My spirituality, sense of self, and ability to remain soft are my greatest weapons here in a world that has tried to kill me.

Fighting White supremacy isn’t always by way of an action; I believe it can also be an embodiment. In my case, it has required a complete rebirth of and a reorientation to everything I was taught about life, including the harmful messages I was fed from birth. Messages like: White is right. Blue is for boys. Skirts are for girls. God loves us all unconditionally, but with conditions. We are only worth as much as we can produce. These messages taught me more about fear and the urge to control those who are different than they taught me about love, acceptance, and appreciation.

White supremacy has an explicit history of using race as the basis to inflict violence on Black people and rob us of our humanity. But it took me a long time to realize just how insidious it is, how malleable. It thrives on disconnection—from nature, from each other, and from ourselves. It thrives on exploitation of the land, culture, ideas, and labor. It uses fear to separate us via racism, classism, transphobia, homophobia, sexism, ableism, and xenophobia.

I believe, then, that fighting White supremacy requires getting more curious, saying yes to all that I have been taught to fear, reconnecting to my body and presence, and developing everyday practices that will contribute to my personal well-being and healing. It requires saying yes to myself every single day.

I have been harmed by many things in this world because of the identities and experiences I’ve inherited. I am a Black man, I come from a working-class and mixed-race family, I am queer, I am transgender, I am incredibly soft, sometimes I find myself somewhere in between genders, and many days I am afraid to walk through the world visibly. I also know that I have a little more freedom and safety to exist only because Black trans women made it possible by saying yes to themselves unapologetically.

White supremacy has created a world conditioned to fear and hate Black trans people, to shun us when we express ourselves outside rigid gender roles, to dispose of us when we cause discomfort in others, to contain us when we have become too free, to punish us when we resist. It draws strength from the trauma it creates, which has haunted our communities for generations. If I am to resist all of this, then, my mandate is to pledge a deep commitment to healing myself as a Black queer trans man and investing in the healing and empowerment of other Black trans people.

I fight White supremacy through an outpouring of love for Black people. I fight by reclaiming my body and affirming my gender identity, my gender expression, and all of my authentic selves no matter how different it was before. I fight by reclaiming my breath, by taking time to slow down and notice, feel, and understand the sensations I encounter and all the things my body does to support me in staying alive.

I resist through meditating, reading books, reclaiming my mind, remembering that what I was taught as a child is not the whole story. Because White supremacy encourages us to remain ahistorical, I resist by reconnecting to my ancestors and lifting up the narratives of those whose stories were intentionally omitted. I resist through creating—art, music, fashion—because I know that capitalism and White supremacy stifle creativity and encourage conformity, efficiency, and production for the sole sake of building wealth for a few.

I resist by establishing boundaries and maintaining them with dignity, by knowing that I have agency over my body, my life, and how I choose to live. I honor vulnerability and femininity because White supremacy has taught us to police and dishonor women and femmes. I trust Black women, especially Black trans women. I talk to my friends and family about White supremacy and how we can all do something about it. I build relationships with other men and seek to foster healing from toxic masculinity and patriarchy, and I encourage us to hold ourselves—and each other—more accountable.

Ultimately, I believe that fighting White supremacy means restoring my own sense of humanity and connecting to the humanity in others. This requires a great deal of healing and empathy for each other’s unique struggles. If I can take small steps toward healing myself—if we all can—then we can heal ourselves collectively. To echo my comrades from Black Lives Matter Atlanta and Southerners On New Ground, who said it best: “The mandate for Black people in this time is to avenge the suffering of our ancestors, to earn the respect of future generations, and be willing to be transformed in the service of the work.”

Wazi Maret is an award-winning, radical fund-raiser, strategist, connector, and creative based in Oakland. He has worked to support and sustain social justice organizations such as the Transgender Gender-Variant Intersex Justice Project, Transgender Law Center, Black Lives Matter, and BYP100, and he comes equipped with years of training and facilitation experience in the areas of racial, trans, and gender justice.

For Alicia Garza, the Future Is Dignified

As one of the cofounders of Black Lives Matter, Alicia Garza’s name is synonymous with harnessing the power of social media to organize and advocate on behalf of Black people in real life. But she was fighting for us long before the masses discovered her Twitter handle, and she is committed to creating a world that will sustain us long after the concept of hashtags has faded from our collective memory. As the principal at Black Futures Lab, the Oakland native is constructing freedom dreams writ large, and she knows it will take all of us to get there. Here she talks strategy with Kenrya.

In one sentence, what do you do?

I’m an organizer, I’m a strategist, and I’m a freedom dreamer.

Dope. Can you please tell me how you came to be an organizer?

I grew up in the Bay Area, born to a single mom who, at the time, had a different plan for what her life was going to look like. When I came onto the scene, she had to quickly figure out how to pivot. Part of what that meant was that she put on her big girl panties and be like, “Okay. I have to make some different choices around what it means to bring a baby girl into the world.”

Coming up, my lifestyle was really influenced by the way my mother hustled. She worked three jobs, and she did that to take care of me. She was raising me, initially, with her twin brother, who moved out to California to support her. She worked during the day, he worked at night, and somewhere in between there, when everyone else was taken care of, she pursued her own dreams. When people ask me, “How did you get into this work?” the answer is that I’m definitely my mother’s child.

Part of how she has shaped me is that she is someone who is not an activist—she’s not even really that political, to be honest—but she raised me with a sense of right and wrong, that there’s a responsibility that I have to leave the world better than I found it.

I got involved in activism at a young age. My first foray was around reproductive justice, getting condoms and contraception into school nurses’ offices. It was a big conversation happening in my school district, and the broader political context was that it was during Bush number one. This was when the right wing really started taking power in this country. There was a big fight over abstinence-only education versus comprehensive sex health education and access to contraception, and that sat inside of a context of what the administration was promoting at the time as “family values,” which you and I both know was really a way to move a White, male, Christian agenda.

As a single mom, my mother talked to me a lot about sex. There was no stork, you know what I’m saying? She was like, “Look, check this out. Sex makes babies and babies are expensive, okay?” She really wanted me to understand the dynamics that come with being able to make decisions on your own behalf with information that helps you do that in a holistic way.

My entry point was around advocacy and service, and it wasn’t until college that I started learning and understanding organizing. Since that awakening, I got trained here in Oakland in the art and science of organizing, and I started knocking on doors in East and West Oakland around issues of economic justice and racial justice. I worked at the University of California Student Association for a little while, helping students of color run and win campaigns on campus for equity and all that good shit.

I spent ten years in a grassroots organization in San Francisco fighting for Black people. The year I left that organization was the year that we started Black Lives Matter.

So we know your origin story. Now tell me about the beginning of Black Futures Lab.

The origin story of the Black Futures Lab starts in 2016. Being one of the cocreators of Black Lives Matter, that was probably one of the hardest years for me personally and politically. It was almost like you could see the storm coming: BLM starts in 2013. Ferguson happens in 2014, and there’s this catalytic series of uprisings that signals a rupture in Black communities, in Black movements, and in Black freedom dreams. This period has really exposed both how Black people are always moving toward a different level of humanity and how there are big gaps and tensions that have really shaped what we think is possible for us.

And 2016 was predictable in some ways. It was the first major election after the first Black president in the history of this country was elected, and so obviously there was going to be a backlash. Then there was the weird positioning from the Democratic Party. It was scary to think about how there would be an extension of the kind of pandering that normally gets done to Black people during election cycles, but that instead it would be shaped around this movement moment and used in incredibly problematic ways.

We were in an untenable position. You have movement and protest happening. You have people pushing an agenda, and then you have an election cycle where there’s really a choice around what you take on as your platform and your vision for the future of the country. What became really clear was that there was no vision from any candidate for what could be possible for Black America. There was a vision for the middle class, corporations, and White nationalists, but there was not a vision for how we move the needle around Black wellness, dignity, and citizenship conceived of in a broad way.

At the same time, we were in a position where candidates wanted to be in proximity to us, but weren’t committed to building power with us. The electoral system itself is not designed for that, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t push for that. What I realized was that there was no way to have that happen unless Black people build political power that is independent and progressive and clear about the tensions and challenges of the electoral system, and also committed to wielding whatever tools are necessary to build the power we deserve.

That is really where the Black Futures Lab comes from. I always use the metaphor of being on a roller coaster that is absolutely batshit crazy and you’re regretting you got on the thing in the first place. You’re like, “I’m never going to make it.” At some point in that process you have to imagine what could happen if you did make it. For me, in holding on tight to that roller coaster, I did a lot of dreaming. If this wasn’t so wack, what would we be doing? What could we do in better circumstances to make this process work for us as much as it can? What else needs to be built to both challenge the system as it is and figure out how to leverage some of the utility of these systems?

The Black Futures Lab comes from that. It’s a freedom dream geared toward transforming Black communities in the constituencies that build independent Black political power in cities and states. It is aware of our current political context, but it is not hamstrung by it. It recognizes that the problems our communities face are complex and that we need to experiment, innovate, and build political power. We can’t cede control over what should be democratic systems to people who don’t want democracy.

We can’t just look at it and say, “Well, those people don’t want democracy, so I’m not fucking with it.” We actually have to say, “It’s ours and we’re going to fight for it.” We have a number of different things that we’re doing, but all of them are geared toward reimagining what Black governance looks like, reimagining what democracy for Black communities looks like, and having a clear vision of what it means for Black communities to have power.

What does that transformation, that reimagining, look like to you?

We have a pretty clear sense of what power looks like. It’s the ability to make decisions for your own life and the lives of people you care about. It’s the ability to shape the narrative of who you are, what you deserve. Power is about being able to implement rewards and consequences based on your agenda. And power is also very much about being able to lead everyone, whether or not they’re in line with your agenda.

I think having that understanding of power then means that we have a different understanding of what we need to do to get it. The big thing that is critical for us at the Lab is that we understand that we need to get more proficient in how and when we build alliances and also understand that those coalitions need to include people who don’t agree with us on every issue and people who might generally share our vision for what’s possible, but have different approaches on how to get there.

If we think about all the people who need to be united to achieve what we deserve, there has to be an incredible diversity within that if we are really talking about building a new democracy. I mean, democracy doesn’t mean everybody’s on the same page, it means that everybody gets to participate in those decisions. And then leadership and organizing are about building a movement that is moving toward your agenda. That’s what it looks like and feels like to us.

How does the Black Census Project move the needle toward that transformative vision of Black power?

We kicked off the launch of Black Futures Lab with that project because we think Black communities are incredibly misunderstood on the left and in the center. Our hypothesis inside the Lab is that the demographics of Black communities are changing very rapidly, but our strategies to engage those changes haven’t caught up. What does it mean that Black people in the United States are increasingly migrant? What does it mean that Black people in the United States are increasingly openly lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming? What does it mean to really listen to what Black people in rural areas are experiencing?

The Black Census Project is a way to reshape our strategies around engaging and activating Black people by saying, “Actually, Black people are not a monolith. Black people in the United States are all kinds of things, and that shapes our perception of what’s happening to us, for us, and about us, and it also shapes our vision for what we want to see.” Our prediction is that in talking to two hundred thousand Black people across the country from very diverse places, we’ll not only expose that Black people are not a monolith, but we’ll also be able to identify opportunities for deeper organizing and learn what is necessary for Black dignity and wellness.

Our goal is to use that data to change the way the institutions engage our communities and send up a flare that we intend to contend for power. And we hope that this project also helps to build the capacity of our movement; most of us don’t talk to two hundred thousand Black people. Hopefully, this data will also sharpen the ways we engage our own communities and help identify new possibilities for collaboration and coordination, which is also necessary for the movement that we need to build.

How does your work with Black Futures Lab help Black people dismantle the system of White supremacy?

We see ourselves as a capacity builder for Black communities. We are not a mass organization that people become members of. That is important work, but it’s a different kind of work. We are building our people’s capacity to govern and lead. And governance and leadership are about solving problems for Black folks, proposing what a different world should look like, and putting Black people in charge of changing systems, structures, and institutions to meet that agenda.

What does freedom for all Black people look like to you?

For me, freedom looks like being able to have dignity. For me, that word and that vision are really important. We could provide a whole litany of the policies we need to change, but for me all that adds up to is: Can Black people live full and dignified lives? Can we live in a way that is cooperative and not predatory? Can we bring our full selves everywhere that we are? I believe very deeply that not only is it possible, but it’s necessary for this planet to survive. It’s my goalpost.

What do you want your legacy to be?

If I’m lucky, my legacy will be that I contributed to energizing and activating a whole shit ton of people to fight like hell for our dignity and we won some shit that was pretty important.

Here we share our own dreams by answering the question: what does freedom look like to you?

Kenrya

There is a playground that sits beside my daughter’s school. It’s nothing special, just a play structure, surrounded by wood chips that are the bane of my existence on Saturdays, when I’m forced to pluck them out of her socks before I can toss them into the washing machine. But one of my favorite things is to watch Saa overwhelm the structure. She stomps to the top, flips her entire body over the rod that crowns the tallest slide, does some parkour-type shit off the fireman’s pole on the far side, climbs up the other side upside down like some kind of fucking ninja, jumps off the ledge when it’s time to choreograph a step with her girls—she devastates that thing. And she does it with a wide grin, a loud laugh, and shouts of “look, Mama,” excited by the time she gets to run and jump and flip, empowered by the strength and agility of her body.

As I watch her I realize that there, tangled in those beige bars, she is immensely free. She’s not thinking about the mean thing her so-called friend said to her at recess, or how long it will take her to run through her violin practice that night, or how annoying it is that Mama is gonna wash her hair before bed. She’s not just living in the moment, she is reveling in it, being her entire self.

There are so few moments that Black people get to experience that type of freedom. The type of freedom where you’re not calculating (and laughing inside at) how “reverse racist” the other moms on the playground think you are when you tell them you’re writing a book about dismantling White supremacy. The type of freedom where you’re not forced to push back against the gaslighting that comes when you tell the administration that you’re pulling your child out of their school because a group of White and White-aspiring kids touched her gorgeous fluffy hair and laughed at it. The type of freedom where you don’t feel a twinge of trepidation the first time you decide not to code-switch when it’s your turn to speak at the parent association meeting.

In my freedom dream, I get to walk around this earth being my complete self at all times without having to worry about someone trying to kick me out of a restaurant because I complained about poor service. I get to call the police when someone majorly harms me without having to worry that the officers will kill me within two seconds of arriving. I get to send my daughter to school without having to worry that she will be suspended for the same minor offense that her White peer was let off the hook for.

We’re not there yet.

But I know a place where we can be our whole, free, Black-ass selves right now: group text.

In my group texts with my closest friends, I don’t have to censor myself. I can share my deepest concerns, celebrate my successes, talk shit about people, and reveal how clueless I am about what’s happening on the lust and Soundcloud beats shows.

And I’m not the only one. Those blue bubbles pop up all day, as my girls share funny tweets, impressive famous dick prints, and rants that we can’t share online ’cause jobs and oppression and trolls and respectability politics and shit.

In the spirit of getting us all free, here are some actual messages that appear in my group texts; names have been omitted to protect the shady.*

A: Question: Do you think one can truly fight for something they may not have experienced? Is it off principle? Or do people truly only fight for things they’ve experienced? Things meaning injustices, abuse, etc.

B: Yes. It sounds like an easy question, but maybe I’m not thinking of it right.

A: I mean, what does it mean to fight? Can you just say you agree with the cause, or do you have to be out front doing the fighting? Or is it enough to just put money out to help the cause? I don’t know. Just some craziness I was thinking about when Jay-Z was talking about racism.

C: I say no. I guess it’s the difference between sympathy and empathy.

A: He’s experienced it. I’ve experienced it, but I don’t know if everybody has truly experienced it. Like sometimes people give textbook answers of how they would handle it, but it’s not always the way you can handle it.

B: Oh, so you are asking if people that haven’t experienced racism and sexism can truly fight?

A: Yes.

B: I think they can, but it’s important to note that fighting can look like different things.

A: That’s true.

B: And I think it’s important because Black people aren’t gonna be the ones to fix racism. It’s White folks. A racist dude ain’t listening to my Black ass. They will listen to someone who looks like them.

C: Wait. Fight is an action. Yes, people can fight for or against things they haven’t experienced. I think people can feel bad for people in a situation. But do they feel the pain? Not the same way.

B: Same with sexism, it’s really gonna take men pulling each other up.

C: I’m not gay. I can march for gay rights, but I can’t feel their struggle.

B: This is a broad generalization—I know the fight is more nuanced.

A: I mean, I guess what I’m asking is just because I show up, do I get credit for fighting for the cause? I’m a number, but what am I doing after that march?

C: Sometimes you just need numbers. *shrugging Black girl emoji*

A: Does fighting or standing up for something mean you do it every day or every chance you get or just that one time or whenever it happens to come across you?

B: I think so. ’Cause a lot of people won’t even do that.

A: That’s true. I mean I was just thinking, Do I fight for anything? Like, I try to stand up for people when I see them wronged, but do I really fight for stuff? Why don’t I? Is it because I’ve been conditioned to fall in line and not ruffle the norm? I don’t know. Is it because I was raised in the South?

B: Do what you can. You can’t fight everything, so do what you can.

A: “She. Is. Playing. Taylor. Swift. In. My. Car. Can I toss her out?”

A: *Pastes in screenshot of an email sent to an annoying coworker.*

A: I sent this and now I feel like I was a little too angry Black woman in it.

B: It’s clear. Was this a repeat issue? Clear meaning, the message was given clearly.

A: Fuck yes. I’m so frustrated with them. But I always try not to be a bitch via email.

B: Not angry Black woman, but annoyed about something you explained before. I don’t think it was bitchy.

C: No. You were direct. Especially if you were clear in your previous email that no action was required.

A: I need new underwear. My booty eats all my draws.

A: I’m not sure why I’m feeling annoyed by the news talking about the girl Jholie Moussa, the teen who went missing and they found her body. They keep showing pics of her that are… provocative. Did she not have any pics where she’s not licking her lips or looking back at it?

B: It’s what they do.

C: *brown finger pointing upward emoji*

A: It’s really blowing me. They showed a scholarly pic of Natalee Holloway. And let’s be clear, she was being hot in the ass in Aruba. Didn’t deserve any harm! But she wasn’t a scholar on sabbatical. She was a teen.

C: Sadly, that’s the norm in media. White supremacy touches everything. *sad downcast face emoji*

A: Maybe I’m cranky, but adult-ass women who wear chokers bother the hell outta me.

B: Lmao.

A: *Pastes in link to article: “Under Ben Carson, HUD Scales Back Fair Housing Enforcement”*

B: He is a disgrace. Damn sellout.

C: I’ve been watching eight minutes of Jerry Springer, watching these two women fight and cuss over a man. They brought this nigga out and I chuckled so hard. He looks like a baby roach! And yes, Ben Carson is a disgrace.

A: *Pastes in link to article: “WATCH: Big Daddy Kane Gets ‘Raw’ for Tiny Desk Concert”*

A: He. Can. Still. Get. It.

B: I love his old ass.

A: Love him!

A: Nigga.

A: Starbucks hired every high-powered Black attorney for help with the Blacks. They couldn’t afford to lose us as patrons or workers. I appreciate the effort if nothing else.

B: They are doing this right. They are definitely trying hard.

A: *Pastes in surreptitiously snapped picture of adorable, clearly freezing newborn baby sitting in a car seat on the floor beside their mama*

A: White. People. This woman has on a winter coat. But she brings her newborn into the pediatrician office in a sleeper. No blanket. WTF??? This baby was just born. Like days old.

B: If you cold, that baby is cold. White. People.

A: Looking for gift ideas. Z’s line is celebrating their anniversary, and I want to get them a gift from the wives. I was thinking this personalized flask and cigar case. But one of them is super religious.… Do you guys have another idea?

B: Tell that churchy muthafucka to chill and put pineapple juice in that flask.

C: It’s so perfect! I want one.

A: Did y’all watch the Black-ish episode about Howard? Why did people like it? I hate it. It basically portrayed HBCUs poorly saying the kids that go there have a hard time adjusting to White folks in the workplace and are not exposed to White life.

B: I didn’t like that either.

C: Same here. I wasn’t a fan. I think This Is Us did it so damn perfectly anyone else would have fallen short.

A: Yup.

D: Yeah, I was upset the whole HU episode too. No one is out of the loop these days, and fuck knowing a White song.

A: Sista… you’ve been on my mind. Oh, sista… we’re two of a kind. Sooooo, sista! *tilted crying laughing face emoji*

A: Am I missing something? This State of the Union is an entire speech of shout-outs. It’s like one long-ass BET award acceptance speech. He’s trash.

B: Ugh. Yeah, not watching that.

A: I know. I need to stop.

C: He’s horrible at this!! He’s sounding out each syllable. This is stupid!!!!

A: You know he searched high and low for Black people.

C: Locking the door on Dreamers to stop gang murder is like killing all White men to stop serial killing. This is insane.

A: I need to stay home today. My PTSD is flaring. My cousin got stopped twice this week coming home from work. Why is it okay for Black people to deal with this shit constantly????

A: “She clearly doesn’t have any real friends. Why the hell did she tweet that instead of posting in her group text?”

Akiba

I never learned how to jump double dutch. I have blamed this fact on my pigeon toes and bow legs. (“My feet point inward, my legs bend backwards. I can’t not step on the rope.”) I’ve gone as far as invoking an undiagnosed spatial problem. While I did manage to bust a blood vessel in my right eye opening a closet door as a kid, the truth is that my double dutch fail comes down to trust. I simply could not trust the inevitably screwface girls whipping that white, hard plastic–coated laundry line to a wicked rhythm. I sucked even when they were kind enough to designate me the “babydoll,” the girl allowed to start in the center instead of jumping into already-turning ropes from the side. I hated that—I had my first-grade pride.

But seriously, name me one thing that is more beautiful than double dutch.

It is so very difficult for observer me to articulate what the end of White supremacy looks like. I can’t tell you which set of policies, political victories, and global shifts will vanquish this crazy-making system. But what I can say is that the art and sport of double dutch offers some possibilities.

For one, double dutch requires a deep synergy with other people. If everyone is in sync, oh the tricks the jumper can do! But if you’re turning double-handed or you’re in the center jumping too slow, the whole enterprise falls apart.

The good thing about messing up in double dutch is that your mistakes disappear with every round. You can be trash at 1:20 p.m. and kill it at

1:32 p.m., after a few other folks get a turn. The reason why you get better doing the same thing isn’t because you’ve had a twelve-minute emergency clinic. It’s because you and the people turning the ropes shift how you work with one another. The democracy of rhythm takes hold.

Most double dutch takes place outside, in the sun, with Black girls in full control of their arms, legs, and minds. They are sweating and counting. No matter how absurd a sexual harasser is, he is not commanding girls to replace their skills-related grimace with a coerced smile.

You cannot leave your body when you’re jumping or turning. The ropes know.

Also, I have seen with my own eyes how Black children who are not cis girls are welcome to learn and play double dutch. Outside of the game, these kids may very well be castigated and abused for being who they are. But within a double dutch context, they’re flying—or failing—alongside the other people playing. It’s all about jumping and turning, not being one way or another.

Try as you might, nobody can jump double dutch alone. And unless you are the rare professional, your team is place-based. The people you struggle with are in your neighborhood or schoolyard, or at your job where a group of sisters decided that double dutch is some of the most fun cardio on the earth.

Of course, like everything everywhere, all the time, double dutch can be problematic. Getting slapped in the face with a rope could happen. The person turning could get a surge of bitter energy and speed up the tempo so much that everyone is forced to quit. People can try to double the ropes to make up for weak spots in the first one, but thicker ropes lead to thicker welts. You can be a grown-ass woman like me who wishes that she’d mastered it as a kid and sees her lack of skill as a cultural forgetting.

But you can also be a grown-ass woman like me who is plotting on joining, creating, or renewing her membership to a league of other adults doing double dutch with varying degrees of skill, dreaming of a crew turning and jumping together in the sun.

* And I added punctuation, ’cause this is a book, not a text message, you heathen. Also, the letters just correspond to who spoke first, second, and so on. So don’t try to figure out a pattern—there isn’t one, and you ain’t slick anyway.