In centuries past, when a king lay dying, there would be great concern among the people. They were sad about losing a ruler they knew. And anxious, too, about getting a new ruler that they didn’t know. The kingdom was changing. What would happen to them? As the old king took his final breath, and his successor became king, a cry would ring out among the people:

“The king is dead—long live the king!”

That is what’s happening to the life stage we call “retirement.” At all levels—individual, organizational, and societal—it’s dying. And it’s dying sooner than we thought. The successor is a new, unknown, and quite different life stage—which will also be called “retirement.” The kingdom is changing. What will happen to you?

While all these changes are going on around you, you’ll be making key decisions about your next stage of life. Because there are no rules for this new version of retirement, you’ll need to design it for yourself. This book will help you make those decisions, and help you design the life you want to live.

Where do you stand now? If you’ve been working steadily toward the old-fashioned version of retirement, you can probably still get there, if you really want to. If you’re anxious about the uncertainties of the new retirement, you can take concrete steps to protect yourself. If you’re curious about the new possibilities that are opening up, you can explore those. And if you don’t think you’ll ever have a retirement (new or old), you can identify what might keep you going. Whatever your situation, you’ll discover something useful here.

You’ll also discover that this book isn’t about just one aspect of retirement. It’s about you, and all the parts of your life. For example, most retirement books focus on finances, and come from the narrow perspective of money and managing the affairs of the world. Other books focus on health, and come from the narrow perspective of medicine and managing your physical body. Still others focus on happiness, and come from the narrow perspective of your relationship with yourself and others. This book is unusual because it integrates all those aspects of your life. So instead of coming from one of those narrow perspectives, this book takes your perspective. It’s you-centered, rather than topic-centered!

To design the life you want to live, you’ll need to do some real research and make some important decisions. However, you won’t find all the information you need within these humble pages. The world—and the world of retirement—is now simply too big and too complicated. It wasn’t so long ago that there was a shortage of information out in the world, and the purpose of a book like this was to collect and preserve that scarce resource. To obtain in-depth information on a specific topic like retirement, you traveled to a repository in the physical world—a library or bookstore. There were only a few designated places where in-depth information was indexed, catalogued, and stored, so that you could obtain it when you needed it. The world was almost like a knowledge desert, and a book was like an oasis of knowledge. In that bygone era (just a few years ago), most people valued books mostly for the content that they offered.

But now it’s the opposite! There’s a surplus of information in the world. There’s more floating around than we know what to do with. From television to magazines to advertising to bloggers to Google searches, it’s simply endless. It keeps pouring in, more and more of it, every day. We are awash in information. And it’s not just of a general nature. Anyone with an internet connection can drill down to find and retrieve the most specific, technical, and obscure tidbits that you can imagine. Although some of what we access is simply data, much of it is actual knowledge. That is, it’s well-considered advice from people who truly know what they’re talking about, within their own area of expertise. The world isn’t an information desert anymore.

Due to the ever-present, immediate, and endless electronic delivery of in-depth information, there is now more of it available outside of books than inside them. If you can obtain knowledge through your broadband connection, then what’s a book for? In this case, the book you’re holding has a more important job than merely providing more information. Its job is to help you understand the sea of information in a new way. As it turns out, there are three fundamental problems with the way the sea of information operates.

The first problem with the sea of information is that it’s actually incoherent. It just splashes around, with no sense of order. So this book provides a coherent structure for organizing information. That way, you’ll be able to bring order to the chaos of the modern information world.

The second problem with the sea of information is that it’s relentless. It’s like a fire hose that’s forever trying to fill you up, as though you were an empty barrel. So this book provides a way to reflect upon, draw out, and crystallize the wisdom you already have. It’s at the confluence of the information stream and your own stream of consciousness, that you’ll make your best decisions.

The third problem with the sea of information is that it’s fickle—the current flows one way and then another. Because there’s no direction, who knows where you might end up? So this book helps you choose your own destination and set a course to get there, no matter which way the winds are blowing.

Unlike the stream of information, this book is something secure that you can get a hold of. Unlike that anonymous information that flows by and is gone forever, when you use this book, you’ll be organizing and clarifying your own information, thoughts, and dreams. (Try doing that with Google!)

Truth be told, there really is a lot of content in this book. Most of it can’t be found anywhere else. But just as important, you’ll find a unique process for designing the life of your dreams. A process that offers a coherent structure, recognizes what you already know, and provides a constancy of vision. When you read this book and do the exercises, you’ll become better and better at navigating that ever-changing sea of information out there. You’ll be the captain of your own ship, sailing toward your own destination.

So—what is the destination, anyway? Where are we supposed to be heading? Why are we supposed to retire? After all, for 98 percent of human history, retirement didn’t really exist!

For eons, most people worked for themselves, and with their families. They were hunters or farmers or fishers or craftspeople or traders. They pretty much kept working into their later years, because they weren’t wealthy enough to stop working. (There have always been a few wealthy people who could stop working, of course. But most people couldn’t.) As they aged, they worked at a slower pace, relying less and less on their physical strength and stamina and more and more on their acquired knowledge and skills. If they were clever and fortunate, they found ways to do more of the work that they liked (and less of the work that they didn’t). But most people couldn’t afford to stop working, and so they kept on, as best they could, as long as they needed to. Except in the case of sickness or accident, withdrawing from work was a gradual process. The human life course had a long and gradual arc, with gentle transitions from one life stage to the next. It was a natural way to live, and it was like that for thousands of years.

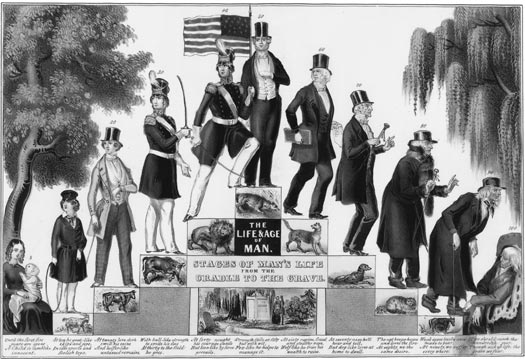

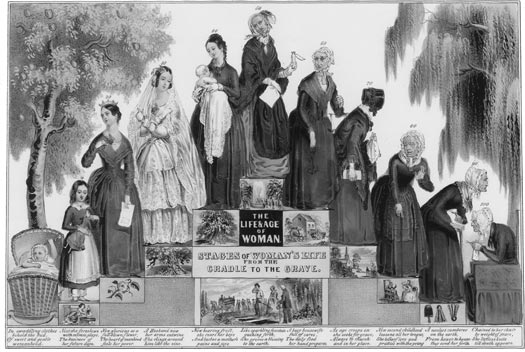

Before the industrial age, life transitions were more gradual.

The Life and Age of Man and The Life and Age of Woman, James Baillie, 1848.

So what happened? The Industrial Revolution! Many of the people who had worked the land or pursued their own cottage crafts went to work in factories for someone else, or for something else—a corporation. Most of them did it willingly, because they could earn more money and improve their material standard of living. The industrial laborer’s life was very different, though. In factories, everything was standardized. All the machines were in rows. All the nuts and bolts were in standard sizes. And people’s activities became standardized, too. Instead of using their unique skills, workers with the same jobs were supposed to do the same things in the same way. Also, people’s working time became standardized. Everyone worked in shifts, with each shift’s workers starting at the same time, taking a break at the same time, and quitting at the same time. At the end of the day, as one shift of workers left, another was waiting to take its place.

The work in factories was fast, demanding, and repetitive. People had always worked hard, but not in such a structured, mechanistic way. As workers aged, they couldn’t gradually slow down. They couldn’t focus more on using their knowledge and skills, as they had in preindustrial times. After all, factories were organized around efficient production, not around the natural life course of humans. Workers were seen almost as a part of the machines they operated. (Charlie Chaplin’s movie Modern Times was a serious comedy on that topic.)

Factory owners decided to get the slower, older workers out of the factory by implementing a new practice: retirement. It was similar to replacing the worn-out part of a machine. After all, with an increasing population, there were plenty of younger, stronger, faster workers ready to fill those jobs. It was also pretty easy to sell the idea of retirement to workers—especially when it included a retirement pension! The jobs were physically demanding, dirty, and dangerous. Much of it was sheer drudgery, so the simple absence of this nasty work, in itself, was a reward. As general prosperity increased, more and more people were able to stop working as they got older. Given the nature of the work, who wouldn’t want to retire?

In the early days of the twentieth century, the Industrial Revolution was getting up to full speed in the United States. The industrial workplace was so different from the old agrarian way of life that experts needed to develop completely new ways of thinking about work, workers, and the workplace.

A revolutionary thinker of the day was Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856–1915). He was essentially the very first management consultant. Taylor’s seminal ideas were outlined in his book The Principles of Scientific Management. One seminal idea was to expand standardization from things (like nuts and bolts) to human behaviors. His goal was to discover the “One Best Way” to do each job and then make sure every worker did the job in that exact way. This thinking sparked a new profession—the efficiency expert—which ultimately transformed the industrial workplace. But it went way beyond industry. This way of thinking spread to construction, the military, offices, professions, and even schools. Peter Drucker, the famous management guru, suggested that “Taylorism” might have been the United States’ most important contribution to new thought since the framing of the Constitution. The impact was international as well: The Principles of Scientific Management sold one and a half million copies in Japan.

We don’t know what Taylor would have personally thought about a standardized approach to retirement. He only lived to the age of fifty-nine. However, the Taylorism movement wanted to standardize everything in its path, and that could have included retirement. Anyway, the idea of a standard approach to retirement is truly a relic of twentieth-century thinking. Isn’t it time to move retirement into the twenty-first century?

Like everything else in the factory, though, retirement needed to be standardized. So employers selected standard ages for retirement. In fact, it was often called the “normal retirement age.” It could vary, but let’s take age sixty-five as an example. At that time, workers who made it to sixty-five were, in general, pretty worn-out. But not all of them. There was a huge variation in how worn-out people were at that age.

It didn’t matter that at any given retirement age, one worker might be as fit as a fiddle and the next one had a foot in the grave. Or that one person loved the work he was doing and was productive, while the next one hated it and barely kept up. None of that was taken into consideration, and for the sake of standardization, retirement was based on age. After all, for employers and employees, age is easy to measure and to specify. How healthy a person is, or how much that person loves the job, is certainly more relevant to the timing of retirement—but that couldn’t be easily measured.

So the die was cast. This standardized approach to retirement, based on age, meant that instead of the withdrawal from work happening gradually, as it had for most of human history, it became an all-or-nothing deal. When the idea of retirement was created, it was created as an event—a specific point in time. Before workers reached the retirement date, they went to work full time, every day. When they reached that date, they stopped working completely, all at once. Retirement was radically different than the more gradual transitions that humans had always known. But it made sense for the factory.

This standardize-everything mentality spread far beyond the factory and into offices and professions. The federal government took the same approach as the organizations that had implemented pensions. When Social Security was instituted in 1936 with a standardized age, that was the end of the story. Retirement became an all-or-nothing event. Retirement became the finish line of life.

In the old retirement, then, the idea of standardization stuck. It stuck with employees, with employers, and with the government. It has stuck around for well over half a century. But you’re not stuck with it. When you go about designing the new retirement, a good place to start is with the transition itself. Could you choose your own timing, and transition gradually, like humans did before retirement was created? Think how different that would be than an all-or-nothing event.

Unfortunately, a retirement finish line can give us a countdown mentality: “Only five years, eight months, two weeks, and four days to go—hallelujah!” A countdown mentality can make us unintentionally put our life on hold. On a more subtle level, it can leave us feeling powerless, as if we were not in control of our lives. It can make us feel that we need to wait until the normal retirement age to become emancipated—when finally, at last, we’ll be set free to do what we really want with our lives.

Or just as dangerously, a retirement finish line may induce us to retire on the standard schedule, even though we’re not ready. What if we’re not financially prepared to retire? What if we’re as healthy as a horse with no signs of slowing down? What if we still find our work or coworkers engaging and energizing? The pressure of the standardized retirement age can make us disregard our own unique situation.

Rather than being driven by your “normal retirement age,” perhaps there is another way that you can look at it. Is your work holding you up or holding you back? Sustaining you or squelching you? Is your job a leash or a lifeline? Those questions may be more relevant in deciding when and how to retire than the age on your driver’s license.

Although your employer, your benefits provider, and the government all use standardized ages for retirement, that doesn’t mean you have to. Instead of automatically accepting some arbitrary ages and dates, you can come up with your own. Then be sure to brainstorm with a knowledgeable expert (or two or three) on how to compromise between your own schedule and those all-important regulations. If you’re short on money, you might need to customize for a later retirement age. If you’re short on health, you might need to customize for more work flexibility. If you’re short on happiness, you might need to customize for your sanity!

Depending on your job and your employer, you may have almost no flexibility in customizing your transition, or you may have a great deal. (If you’re one of the ever-growing numbers of entrepreneurs or solopreneurs, you have carte blanche—so you can get really creative.) In some cases, employers are willing to bend over backward to accommodate workers, and in other cases they won’t bend an inch. If your knowledge or skills are in high demand and low supply, your employer may be eager to entertain your creative ideas about a “flex retirement.” But if your employer sees you as just one more cog in the machine and imagines that there are plenty more cogs where you came from, you don’t have much bargaining power.

Your flexibility in your job, with your employer, in your industry is ruled by the particularities of your situation, rather than the generalities of the marketplace. You won’t know how much you can customize your retirement transition unless you try. Also, you know best what the culture of your workplace is—and how close to the vest you need to keep your retirement cards. At some organizations, if an employee so much as admits that some day, in the far distant future, he or she might possibly want to retire, the employer will immediately suspect that the worker is starting to slack off and not taking the job seriously. If you know that to be the case at your organization, you don’t need me to tell you to be discreet! If, however, your organization is one where you can be upfront about your long-term and short-term plans, that’s much better for you and for your employer, too. Remember, you and your employer are both making up new ways of transitioning to retirement. You may need to be a trailblazer to customize your transition. Just be careful not to get burned!

Here’s a list of ideas, just to spark your creativity. You might:

1. Change to a career you love, that you could do forever, more or less. (Probably less.)

2. Start a business on the side, and keep it going after you retire from your regular job.

3. Slash your living expenses, save like a crazy person, and take an early retirement offer. (But be ready to work again, if need be.)

4. Take early retirement like #3, but plan to try a new career. So what if it doesn’t workout?

5. Refocus your job on what you do really, really well, then retire late because you’re so valuable.

6. Get rid of the worst parts of your job, then work part-time to do only the best parts.

7. Negotiate a phased retirement, where your employer lets you taper off over months or years.

8. Open the door to a revolving retirement, where you come back periodically or for specific projects.

9. Take a standard retirement, then work for a customer, a supplier, or even a competitor.

10. Take a standard retirement, but become a consultant in your field. (Many people claim they’re going to do this, but never follow through. Are you different?)

CAUTION: Finding a way to stretch your transition can be difficult, but it increases your financial security. Finding a way to cut short your transition can be easy, but it decreases your financial security. Always look before you leap.

Changing the way we transition to a stage of life is an important issue. There’s an even more important one, though. What are the life stages themselves? Could you make up your own life stages, if you wanted to?

Let’s start with the standard-issue life stages, and transitions, the way most of us were brought up to think of them. The retirement event has been the doorway from the life stage of work into the life stage of retirement. And much earlier, another event—graduation—was the doorway from the life stage of education into the life stage of work. These transitions divided life into three stages: education, work, and retirement. These have been so rigid, and so closed off from each other, that we could even think of them as boxes. (This idea was first put forth by Richard N. Bolles in his book The Three Boxes of Life.) They look like this:

For most of human history, these boxes didn’t exist for most people. Children farmed and fished and crafted with their families from an early age. Then, when the Industrial Revolution happened, children went to work in factories instead. (It sounds appalling to you now, doesn’t it?) When economic prosperity increased enough, society was able to create the education box. There was a cost to doing that, but it was an investment in the future. The education box directed the people in it toward the activities of learning and self-development. That meant that only adults would be in the box called work. They were the ones directed toward the activities of working and being productive. Finally, when prosperity had increased enough again, we created the box called retirement. There was a cost to society for creating that box, too.

The retirement box was unique in one way, though. Instead of being defined by what the people in it could and should do, it was defined by what they couldn’t and shouldn’t do! Specifically, they shouldn’t be learning and developing. And they shouldn’t be working and productive, either. You know the story of how the old retirement was born: It was created for older workers who were too worn-out to learn anything or produce anything new. There’s a name for what they could do—it’s called leisure.

So, across the life course, we were supposed to first focus on self-development (the first box), then on being productive (the second box), and then on leisure. So the contents of the three boxes look like this:

When young people are in the box of education, their parents, teachers, and peers create an environment that pretty much tells them what to do. They may think they’re “doing their own thing.” But if they get off course, others in the education box usually straighten them out—in a well-meaning way—and put them back on the standardized path. So when it comes down to it, the first box doesn’t allow much freedom. Society in general, and families in particular, must provide support for that box, so they run the show.

Likewise, when people are in the box of work, the supervisors, coworkers, and their own professional expectations keep them in line. Although they’re adults, the environment pretty much tells them what they should be doing. They definitely have more freedom and more choices. But society needs people in the second box to support the ones in the first and third boxes, so they pretty much keep their noses to the grindstone.

What about the retirement box? When the old retirement was created, the people in it were retiring from old-fashioned factories or other demanding work, and typically in declining health. Most of them were going to live only a few years in retirement. They were retiring to a life of leisure, because that’s all they were capable of. And unlike the earlier boxes, there weren’t many societal expectations. No parents, teachers, or supervisors to keep retirees in line. They were left alone, to do whatever they wanted, with the short time they had left. Society and employers provided significant economic support for this nonproductive life stage through Social Security and retirement pensions.

This was a major achievement of modern society. All three boxes were in place, and supported by societal institutions. Everyone knew what they were supposed to be doing, and when they were supposed to be doing it. The structure and funding for education was in place, and working pretty well. The structure and funding for retirement was in place, and working pretty well, too. After thousands of years of gradual life-stage transitions, the human life course had been changed forever. It was now neatly divided into three well-defined boxes. Society was great!

Then, as time went on, something amazing happened. The retirees didn’t die. Well, they died, but not as soon as expected. For a variety of reasons, they kept living longer. Each group of retirees lived longer than the previous groups had. And they weren’t just living longer, they were healthier and more active, too. The leisure box extended, and the Three Boxes of Life changed to look like this:

At the same time, workers were looking at the old retirement and deciding that they’d like to get there as early as possible. With personal savings, employer pensions, and Social Security, the average age for retirement became younger. The productivity box shortened a bit, and the leisure box was even longer. The three boxes looked like this:

The retirement stage of life had been transformed. Instead of being worn-out and sick for much of their retirement, people were healthy and vital. Instead of lasting just a few years, retirement stretched out to a decade or more. And because no one was telling them what to do, retirees could do whatever they wanted. Some decided that an entire life stage based on leisure didn’t make sense. They forgot (or never knew) that productivity and development were supposed to be off-limits. They took up formal and informal learning, new careers, significant volunteer work—you name it, they did it. They mixed up development, productivity, and leisure all in one box! They made the earlier, healthier part of retirement into a completely different stage of life than the old retirement was supposed to be. Only the later part of retirement looked like the original idea, as people became frailer and were winding down their lives. It looked like this:

In the 1980s, a historian at Cambridge University by the name of Peter Laslett had anticipated what would happen. He knew that the original idea of retirement—the old retirement—couldn’t stretch enough to fit what was happening in the world. He saw that the healthy, active, early part of retirement wasn’t very much like the frail, inactive, later part. They were altogether different ages of life. At the same time, the last years of the second box were becoming more and more varied. Some workers were retiring, or semi-retiring, in their fifties. They were still supposed to be in the second box but were living more like the healthy, active early part of the third box. Laslett realized that to understand what was going on, and to make plans for ourselves, we needed a fresh map of life. It looks like this:

Laslett’s description of the First and Second Ages are equivalent to the first and second boxes. His description of the Fourth Age has similarities to the original industrial-age retirement—sickly and short. But his concept for the Third Age is something else altogether. He recognized that for the first time in human history, we were creating a life stage that had significantly reduced responsibilities—but also continuing health and vitality. As people at midlife were gradually freed from child care and work, what would they do with that freedom? He suggested that this newfound opportunity could be the peak of human achievement. Rather than being over the hill, people could be climbing the summit of life. They could develop themselves to their full capacity and attain their greatest degree of life fulfillment. He even referred to it as the “crown” of life! Rather than defining it by specific ages, he suggested that the Third Age is defined by an orientation toward life. Laslett was a good role model, as his book on this subject was published when he was seventy-four. For many of us, the Third Age is most likely to occur between the ages of fifty and seventy-five. We may be working, retired, or somewhere in between. But that’s less of a factor than our commitment to fully explore, develop, and express ourselves. The fact that you’re reading this book right now is an indication that the idea of the Third Age probably appeals to you.

What interesting new combination of work, learning, and leisure would you like to create? The more creative you are, the less retirement income you may need. In our consumer culture, advertising tries to convince us that happiness can be found mostly with a credit card. It can take tons of money to fund a retirement that’s based on all leisure all the time. You could be saving up forever to afford such a retirement.

In contrast, learning is pretty inexpensive. Public universities and community colleges often provide courses at nominal cost for retirees. Many faith communities sponsor programs for both self-exploration and socializing. Nonprofit entities such as Elderhostel sponsor low-cost opportunities to explore and learn about the world. Senior-level athletic events are also becoming more common. On a more individual level, you’re free to explore hobbies or activities that are based on self-development rather than entertainment. Self-development can be a bargain.

Productivity can be even better than a bargain. It can cost as little or as much as you’re willing and able to spend, and the result is often making money rather than spending money. One form of productivity is paid employment, which might help make ends meet. Or if you can afford to, you may choose to be productive as a volunteer, for no pay. And you may even find something in the middle—such as a job that pays less than you’d normally accept—so you can do something more important to you than just earn a paycheck.

For each of us, the right kinds of self-development and productivity can be just as satisfying as leisure—or even more satisfying. Add all this up and it’s clear that a life stage based on three types of activities—leisure, self-development, and productivity—may allow you to live on less money than a leisure-based retirement would cost.

If you’re thinking this new Third Age approach to retirement might work for you, then the next question is, when can you start? If you’re not going to be “over the hill” at any particular age, but will still be climbing the summit, then you don’t need to retire based on some arbitrary calculation of how many years you’ve been on earth. After all, chronological age is only one way to think about where you are in your life’s journey. (Biological age is another way—but we’ll get to that in chapter six.) You may retire “early” for your age, or you may retire “late” for your age. So instead of thinking about chronological age, try thinking in terms of your life stage—what’s actually going on in your life.

If you’re still carrying the heavy burdens of raising children (or paying their expenses), pushing to keep going strong in your career, or paddling to keep your financial head above water, you’re squarely in the Second Age, no matter how old you are. (Keep going—you’ll get there!) On the other hand, if your children have flown the coop, if you have the choice at work of pushing hard or easing off, and if you’ve salted away enough money to make a paycheck optional, you may be ready for the Third Age, even though you’re not ready to retire. Instead of the all-or-nothing old retirement approach, perhaps you can make a more gradual transition—as humans once did, naturally, for millennia. You can withdraw from work on your own schedule, and mix and match it with learning and leisure, however you want!

Just to get your Third Age imagination going, here are some questions to ask yourself about the three types of activities:

1. Self-Development. What do you really want to learn about, or how have you dreamed of investing in your ongoing development? Can you imagine exploring career options that would allow you to somehow get paid to learn or develop in this way?

2. Productivity. If you were determined to work at something that you absolutely love, what might that be? Could you afford to earn less money doing it—or even do it without pay—solely for fulfillment and satisfaction? Can you imagine exploring career options that would allow you to get paid to work at something you love?

3. Leisure. What have you wanted to do, just for the sheer pleasure of it, but productivity and self-development seemed always to take precedence? As crazy as it may sound, can you imagine exploring career options that would allow you to somehow get paid to play?

If the Third Age sounds like crazy talk to you, and you just want to think about the old retirement and taking it easy, don’t feel guilty. It’s OK if you just want all leisure, all the time. You could be, like the original workers, just plain worn-out from all the work of the second box. You may really need to do absolutely nothing but enjoy yourself—without trying to be productive or self-developing—for a while after you retire. Farmers know that a field that’s allowed to lie fallow for a year will yield a better crop the following year. That may be the case with your retirement; you may find you want to do something else later, after you’re fully rested and recharged. In fact, you may surprise yourself.

This new way of thinking about the stages of life has folks in a lexical quandary. Because it’s so different from the original idea of retirement, some people don’t even want to call this new life stage retirement. They’ve come up with labels to try to articulate what a huge shift it represents. Here are some terms that you might see:

• The New Retirement

• Re-Firement

• Re-Wirement

• Rest-of-Life

• Second Half of Life

• Unretirement

• Re-Engagement

• Second Adolescence

• The Bonus Years

The change that’s happening may ultimately be as profound as the creation of the original old retirement was. But we think that in terminology, a strange thing is likely to happen. As more and more people take this new approach—of greatest freedom, mixing it all up, development and productivity and leisure—it won’t seem so unusual anymore. It will eventually become the normal thing to do. People will ask, “Wasn’t retirement always about development and productivity and leisure?” The original idea of retirement of all leisure, all the time will have faded away, and this revolutionary new approach won’t even need an alternative name. This radical new life stage will eventually come to be called, simply, retirement.

Retirement is dead—long live retirement!

Retirement is changing in many ways, and for many reasons. What was true in the past may not be true in the future. With so much uncertainty, how can you design the life you want to live?

Before making the big decisions about your retirement, think through these fundamental principles. Keep them in mind as you develop your specific strategies and tactics, and you’ll be building on a firm foundation. Forgetting about them could lead to a shaky retirement!

1. Retirement is a career transition.

Your transition may be away from work completely or from one career to another. The transition can be all at once or happen gradually over time.

2. Retirement can be voluntary or involuntary.

You could choose the timing, or you might be terminated even though you want to keep working. You may think you’re temporarily unemployed, but discover later that you’re retired.

3. Retirement is a stage of life.

Your retirement is not only an event, but a life change that occurs over a period of time. Your experience is unique, and yet it also has much in common with many other adults.

4. Retirement includes biological aging.

Your body ages over the course of retirement, which results in decline and death at an unknown future time.

5. Retirement requires economic support for an unknown time.

For you to remain retired, sources of material support must continue for as long as you live.

6. Retirement changes your level of engagement.

Retirement increases or decreases your psychological engagement, and increases or decreases your social engagement with others. Both tend to decrease over the course of your retirement.

7. Retirement is shaped by earlier life stages.

All the domains of your life prior to retirement will affect your life during retirement.

8. Retirement well-being includes prosperity, health, and happiness.

Your well-being doesn’t come from economic security, physical health, or life satisfaction, but from all three in combination.

“Without ignoring the importance of economic growth,

we must look well beyond it.”

—AMARTYA SEN, winner of the 1998 Nobel Prize in economics