When physicists like Einstein and Hawking reference the nature of space and time, they’re asking questions about the nature of reality itself. But we’re only asking questions about where to live in retirement. In comparison, that might seem a bit trivial. But isn’t it all relative?

Have you known people who stayed in the same place as they aged, long after they should have moved? They clung to a particular home, neighborhood, or part of the country. They were somehow immobilized, for one reason or another, even when it became more and more difficult to stay there. Living in the wrong place came to dominate their life. Then, when they finally relocated (if they ever did), they announced, “I should have moved long ago!”

Or just the opposite—you’ve known people who couldn’t wait to relocate for retirement. They fell in love with a particular home, condo, or apartment. Perhaps they discovered a real estate development, or just a neighborhood, that offered exactly the amenities and activities they had dreamed about. Off they went, with great anticipation and excitement, to inhabit this new place. Then, for one reason or another, it didn’t live up to their expectations. They were disappointed. But they stayed in the new place because it was too difficult or too expensive to relocate. Or perhaps they did set off once more, in search of yet another new place. Or, as sometimes happens, they retraced their steps and simply moved back to where they had come from, more or less. They were disillusioned, if not defeated.

Of course, there are stories of success, too. Many people stay in the same place, and it works out perfectly. Or they move somewhere new, and it fulfills their expectations. The question is this: How can you predict, in advance, how well a certain place might work for you?

This chapter answers that question. It offers you a new perspective and a practical approach for understanding the places where you might live in retirement. Equipped with this new perspective and approach, you’ll see the pros and cons of moving or staying where you are now.

Most of us at least daydream about moving somewhere new. It could be just across town or across the country. Either way, letting go of the place where we live and making a new home somewhere else is one of the most adventurous things we could do. Even the old-fashioned, leisure-oriented approach to retirement was exciting when it included a move to a new location. (Sun City, here we come!) Any move is an adventure, after all.

It’s easy to imagine moving, but it’s not easy to know whether that move would really support your retirement well-being. Or if you imagine staying where you are, it’s not easy to imagine how well your existing place will serve you in the future, as you get older. Geography is an important decision, because it affects almost every aspect of your life—financial, social, psychological, biological, and medical. Let’s peek at those connections.

Your geography and finances are linked not only by the cost of your residence itself but also by the general cost of living that goes along with any particular location. If necessary, we can almost always find a place to live that’s cheaper than where we live now. Or coming from the other direction, if you plan to work in retirement, geography will help or hinder your ability to do that. It’s easier to make money in some places than in others. Where you live can affect both sides of your cash flow statement: expenses and income.

Location has an enormous effect on your social relationships, too. As much as you want your social ties to transcend distance, you’ve probably spent more time with friends and family when it was geographically easier to get together with them. The place where you live affects you psychologically, too. Hopefully it provides you with outlets for exploring your interests and using your skills. In retirement, you’ll either be engaged and stimulated by your environment or lulled into boredom.

Finally, geography will affect your health in two key ways. Where you live impacts your healthy living habits, such as being physically active. Retirement offers more free time, and your geography will shape what you do with that time. Will your environment help get you moving and build your biological vitality, or will it shut you down, prematurely aging you? Even if you do take better care of your body, sooner or later you’ll seek out more medical services from practitioners and institutions. Will your retirement geography be a help or a barrier to getting the treatment you want?

Even if you decide to stay right where you are when you retire, that decision raises all the same questions that a new place would. You should still look at your location with fresh eyes and evaluate it from a new perspective. Will it support the kind of life you really want to live? Would a few changes make your current place into your dream place? How do you know what your dream place is, anyway? Your life changes so much from the Second Age to the Third Age to the Fourth Age that your dreams change, too. The place that was perfect for raising your kids and commuting to work may not be perfect anymore. Your dream home from the Second Age could even become a nightmare in the Fourth Age.

Not only is your choice of where to live a profound decision, it’s also a high-stakes one. Making a move is such a major undertaking that you are unlikely to undo it, even if you get it wrong. If you discover you made the wrong choice, you may settle for just settling in because it’s too difficult (and too expensive) to move again. Another move would likely be to another new place. You surely know the expression “You can’t go home again.” (That’s because someone else is probably living there now.)

On the other hand, if you make plans for retirement based on not moving and then design a life around your existing place, it can be difficult to reconsider later. There are, in life, certain windows of opportunity. Leaving your long-term career (and daily commute) is a major life transition that opens the window to living in a new place. If you don’t make your move during that transition, the window may close. The window may be stuck—and you may be stuck, too.

The Four Ages depict the life stages, and life transitions, that are emerging in society. As you move from the First to the Third Age, your degree of freedom tends to increase, and that means more geographic freedom as well.

In the First Age, you lived wherever your family lived through high school, and perhaps college, too. You typically didn’t have any choice about where you lived. It was just a given. Unless your family moved, you probably didn’t think about moving. (There are those of us, though, who dreamt of faraway places from a very early age.) If you had a chance to go away to college that may well have been your first glimmer of geographic freedom. And for most of us, even that was quite limited freedom.

The Second Age opened up new horizons. You had the power to choose where to live. But the need to support yourself meant getting a job, which put limitations on your geographic freedom. You may have also been limited by a desire to be close to friends and family. Over the years, your work may have been a deciding factor, keeping you in place or moving you around. Having children may have kept you close to family for support. Getting your children into the schools you wanted for them may have shaped your geographic choices, too.

Yes, the Second Age is filled with responsibilities, and many of those have geographic requirements. But the Third Age offers the greatest freedom of place that you’ll ever experience! Here are five reasons:

1. Your income may not be tied to living in a particular location. Unless you’ve been a telecommuter or a freelancer or you’ve done some other your-presence-is-optional type of work, your income and your geography have always been joined at the hip. But that loosens up in retirement. Once you’re receiving benefits, the Social Security Administration (and your pension plan, IRA account, bank, and so on) will send your monthly check wherever you tell them to.

2. If you want to work in retirement, you may be more geographically flexible in your search for work than you could be in the job that you retire from. Whether you work for the income, to use your strengths, or to be socially connected with other people, you can probably find work in a variety of places. There are even more options when you’re open to—or even prefer—temporary or part-time work.

3. Your residence may appreciate in value by the time you retire, allowing you to sell it at a hefty profit. Or even if your residence doesn’t appreciate, it may be much more expensive than a similar place in another location. In particular, if you live in a region or a metropolitan area with a thriving economy that has plenty of jobs and moneymaking opportunities, people still in the workforce will be eager to buy your residence. They need to live somewhere convenient for their work. But once you’re retired, you may not need that same proximity. Many great places to live have poor job opportunities, which may not matter to you one bit!

4. Family responsibilities typically lessen in the Third Age, so geographical constraints loosen. As your brood left the nest (or flew the coop), they may have stayed nearby or moved across the country. But either way, you’re not responsible for them. Staying connected with your family and being an important part of their life are affected by your geography, to be sure. But connection requires less proximity than responsibility did. In retirement, you may use your increased free time to visit them or stay in touch in other ways. If you live somewhere really cool, they may even be the ones who want to come visit you!

5. People you already know are blazing new trails for you. You have family, friends, and acquaintances who have moved to other places already, and they can provide you with opportunities to try out a different geography. It’s an opportunity for you to sample places where you may want to live. You may have had less communication with them since they moved, but planning your retirement is the perfect opportunity to reconnect with them, and possibly connect with the place that they’ve moved to. Getting inside information from the people who actually live somewhere is infinitely more informative than staying there on vacation.

It’s great to have more geographic freedom, isn’t it? Now what you need is a simple way to consider all the places you could live and compare them to where you live now. So on to this new perspective and new approach to analyzing your retirement geography.

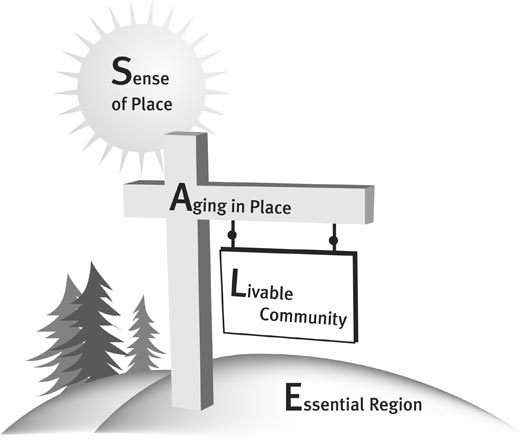

It’s useful to think about any place in terms of four layers, the names of which form the acronym SALE. See the image that makes the acronym easy to remember.

S is for sense of place. The innermost layer, it’s the meaning that you derive from a geographic location.

A is for aging in place. The micro layer, it’s what most people hope to do in their retirement residence.

L is for livable community. The middle layer, it’s a supportive environment for retirement and aging.

E is for essential region. The macro layer, it’s the part of the country that you absolutely must live in.

Does this acronym mean you should sell your place and move? Not at all. But you should at least evaluate your current place according to these four layers. That way, if you decide to stay there, it will be the result of a conscious decision. Consider the four layers in any order that makes sense for you. We’ll explore them one at a time, starting with the big picture.

Assuming that you really could pick up and move to another part of the country (or another country altogether), where might that be? You may have visited other regions for business, while on vacation, or to visit friends or family. Certainly there are regions that you’re curious about, or even attracted to deep down, but have never been to. Retirement may be just the opportunity you’ve needed to visit those places or hang out in them for a while—for weeks, months, or even years. But although retirement can have a vacation quality, it’s important to make a distinction between the places you plan to sample and the one or two places that you may really want to call home. You know that expression “It’s a nice place to visit, but I wouldn’t want to live there”? It’s not just a cliché; it holds a deeper wisdom than we give it credit for.

Whether a region is just nice to visit or is one where you’d happily live out your days depends, of course, on whether that region holds what you need to truly live. When you think about the life you want in retirement, there are probably certain things you can’t imagine living without; you view those as essential. If some of your essentials are tied to a geographic region of the country, then that makes it an essential region for you.

Now, you may not have an essential region. Your essential requirements may be the kind that can be found in many geographic locations—say, a first-rate symphony, year-round golf, a professional sports team, or a huge outlet mall. But a good way to explore the possibility is to consider what you absolutely couldn’t live without, then see whether those things are connected to a particular area.

To identify your essential region, ask yourself these questions:

1. Is there a region that supports you socially—that is, your most important relationships? Where are the people who are essential in your life (possibly children, grandchildren, lifelong friends, elderly parents)? You may not need to be right next door, but within easy traveling distance, perhaps? Consider, too, that these loved ones may relocate someday.

2. Is there a region that offers compelling opportunities to use your skills or strengths in a way that’s psychologically engaging for you? This could be a particular retirement job, an unusual volunteer opportunity, a chance to go back to school, or a once-in-a-lifetime special project, such as working to help protect the flora or fauna of a threatened ecosystem.

3. Is there a region that would allow you to pursue your interests or passions in a way that you could nowhere else? This could be physical geography like mountains or water, or cultural offerings such as the arts or entertainment.

4. Is there a region that could be particularly supportive to your health, especially if that might become more of a challenge, as you get older? You may need a climate that’s beneficial to a physical condition, or proximity to uncommon medical specialists or alternative practitioners. Even basic access to medical care, such as a Veteran’s Administration hospital, HMO, or PPO, could be a factor.

5. Is there a region that would make it easier to make ends meet financially, if that’s an issue for you? This could mean a lower cost of living or the chance to pool resources with family or others as a way to cut costs.

6. Is there a region that’s somehow connected to your deepest values? It could be the center of your religious tradition, cultural heritage, or family roots.

7. Is there a region that would uniquely support your chosen ways to live? This means the area somehow pulls together the social, psychological, biological, medical, and financial elements to support the life you want to live.

As you answer these questions, keep in mind that retirement changes over time. What’s important in early retirement is different than what will be important in later retirement. At the beginning, in the Third Age, you’re young and healthy enough to be very active in the world, so amenities and opportunities are at the top of your checklist for evaluating regions. Toward the end, in the Fourth Age, you’ll likely want and need more help and support from others, and you may need significant medical care. This evolution may necessitate two migrations during your retirement. A first migration could be made so you can do the things you want to do. Demographers call this an amenity migration. A later move to get some help from your supportive relationships is called an assistance migration. That could be to a new place altogether, wherever your family happens to live. Or it could be back to the region where you lived before—a reverse migration. It’s not that you made a mistake and moved to the wrong place. You may have moved to the right place for the Third Age but know in advance that it won’t be the right place for the Fourth Age.

Keep these migration types in mind as you think about what’s important to you and where that’s located. Your essential region for retirement may be a place that’s very different from your essential region for your working years. And if your essential region has anything to do with people (and I hope it does!), your essential region could change if those people migrate. After all, you may be looking at thirty years of retirement.

Of all the changes in geography that you may consider, migrating to another region is the most expensive, labor-intensive, and logistically complex, and it has the greatest effect on your relationships. It’s also the least common. You may already be living in your essential region and just haven’t thought of it that way! All this adds up to the obvious conclusion that migrating to another part of the country is a level of geographic change that you need to research and consider most carefully. With a fresh perspective and a bit of ingenuity, you may be able to create your Ideal Retirement in the region where you already live. Perhaps you could instead make changes at another level, such as your community or residence. (In which case you might decide that another region that had beckoned you is a nice place to visit, but you wouldn’t want to live there!)

What exactly is a community? For purposes of your retirement geography, think of a community in the broad and varied sense of the term. It’s simply an area that you live in during your retirement, and it usually has little in common with that specialized planned development that’s marketed as a “retirement community.” Livable community, as the middle layer of your retirement geography, is the area around your home that you typically travel within to fulfill your daily needs and desires.

Think about your current community. How far do you need to travel to the coffee shop, the grocery store, your faith community, the pharmacy, the post office, the doctor, the library, or dinner and a movie? How much farther, if at all, do you travel to see friends and family? How much farther for something a bit out of the ordinary, such as an airport, a major sporting event, or a top-notch regional hospital? (Although in the later years of retirement, having a hospital close to home could well become more essential.) Whatever area you travel within to fulfill those daily needs is probably what you think of as your community. At some distance from home, you know the feeling that you have left your community behind.

If you think you might even consider looking around for a new community for retirement, it’s worthwhile to think about all the different kinds that exist. In looking at types of communities, you might even redefine what you think of as the boundaries of your own community.

A community can be described in a number of ways:

• It could be a political entity with easily identifiable borders, such as a city or county (for example, Santa Fe, New Mexico, or Door County, Wisconsin).

• It could be a political entity that is contiguous with others but still retains its own character (such as Sarasota, Florida).

• It could be an area bounded by certain landforms or by water (such as Cape Cod, Massachusetts, or Bainbridge Island, Washington).

• It could be a well-known urban area in a large city (such as Buckhead in Atlanta or Wrigleyville in Chicago).

• It could be an area shaped by the presence of a university or other institution (as Clayton, Missouri, is by Washington University).

• It could be a real estate development organized by a corporation (such as Sun City, Arizona).

It could even be what was once called a neighborhood, even if it doesn’t have a specific name (but these are getting harder to find). Many large cities have these enclaves, but knowledge of what makes each neighborhood special may be jealously guarded by locals.

Communities are wonderful things; more wonderful still is a livable community. This concept is a fairly recent one, but it is developing rapidly. Livable communities are good for everyone, whether they’re in the first, second, or third box of life. In fact, one of the features that can make a community particularly livable is that it integrates people from all three boxes. Rather than separating age groups—young singles, families with children, retirees—from each other, all are included. People have lived in these kinds of age-integrated communities for most of human history, and there is a deep wisdom in it. You may even have spent your childhood in an environment like this, and you probably benefited greatly from your interaction with retired folks. They probably benefited from their interaction with you, too!

At the same time, there certainly are livable communities composed mostly of retirement-age people. Where these arise organically through the maturing of a neighborhood, they’re called naturally occurring retirement communities, or NORCs. On the other hand, where these are created synthetically through land development, we might call them developer-organized retirement communities, or DORCs. Not all DORCs are created equal, and a few are even shining examples of livable communities. But please recognize that although DORCs always look very nice, looks can be deceiving. They may be more “lookable” than livable.

You can start thinking now about your current community and how livable it may be through your retirement years. After you retire, your awareness of the community may be heightened. For example, you could become more aware of how rich and varied the available activities are. In looking for activities, memberships, and environments to invest yourself in, you’ll be able to explore your community at a deeper level. One part of that exploration will be getting to know other people in your community to build fun, engaging, and meaningful relationships with (because you’ll be seeing less of your old friends from work). The more interesting and vibrant the activities are in your community, the more rewarding your explorations can be. The good news is that those activities attract interesting and vibrant people (like you!).

Is your community up to the task of being a livable community for your retirement? Or is it a dud? And you may want to gaze into your crystal ball. Not only will your own life change over the coming years, but the life of your community will, too. Is it the kind of town that relies too heavily on just one or two industries, with a Main Street that’s been abandoned as strip malls sprout just outside the municipal limits? Or is your town too appealing for its own good, attracting newcomers from pricier areas, so longtime residents’ children can no longer afford a starter home (if they can find one)? As your community develops, do you see yourself wanting to live there more than you do now, or less? Is there another community, or are there several (right in your own backyard), that would be a better fit? Only by making a comparison will you know. You may discover that yours stacks up very well and you didn’t even realize it. Lucky you!

Another facet of your community is more mundane: How self-contained is it? For many, retiring from work also means retiring from commuting. Commuting is an activity that automatically routes you near many services that you need. In fact, you’ve probably become a loyal customer of some retailers just because they’re on your commute route. Or you may have gotten into the habit of shopping or running errands near your workplace. At lunch and along the way from home to work and back again, you may often fit in the side trips needed to keep the household functioning. They’re just stops along the way. But once you don’t need to commute, if those services aren’t available in your community you’ll need to make specific trips to obtain them.

You might think that’s a good thing in retirement—it will get you out of the house and into the world. That may be true for some folks. But because you’re reading this book, I suspect you’re not looking for meaningless time fillers just to keep yourself busy in retirement. You’d prefer to take care of as many of your needs as easily and close to home as possible. Sure, you want to get out of the house, but for meaningful, engaging activities. If your retirement has the potential to be the high point of your life’s journey, it would be a shame to spend it running errands, don’t you think?

Some communities are called by a single name and thought of as a single entity, but they are actually composed of several self-contained neighborhoods. Their lucky residents can fulfill their daily needs within just a few blocks from where they live. If they walk those blocks (in decent weather) instead of driving a car or taking public transit, they tend to stay more physically fit. The more activities they can participate in within walking distance, the more likely they are to know their neighbors, shopkeepers, librarians, pharmacists, and other nice folks. As people make their way further and further into the third box of life, these relationships become more valuable.

These self-contained neighborhoods exist in every region, in most cities, and in both low-rent and high-rent districts. Many smaller towns still operate on this principle. If you’ve never lived this way before, you owe it to yourself to experience it. Go stay a while with a friend who’s fortunate enough to live in one. For a vacation, sublet an apartment or a house in an area that appears to operate this way (even though you may not get to know many residents in that short a time). There are no advertisements or marketing brochures (let alone salespeople) for these neighborhoods. They aren’t trying to entice anyone, so you need to seek them out. You need to be a sleuth!

On the other hand, there are also places that are called “communities” but are communities in name only. You’ve seen the signs at the gates of developments: “A Community for Those 55 and Better,” “A Community of 38 Distinctive Homes,” “A Community for Active Living!” These places, whatever you call them, often put their residents at a disadvantage, because they don’t offer what people actually need to live day to day. (Unless all you need to do is play golf or tennis or swim.) These “communities” are isolated enclaves that force residents to rely on a car or public transportation, which can be an inconvenience or a hardship, depending on the situation. (Strangely, both gated communities and ghettos can share this limitation.) Because residents don’t walk to the services they need, exercise isn’t as naturally integrated into their daily lives. Because they don’t walk outside as much, they are less likely to know their neighbors and others outside the gates.

As you move from the Third Age into the Fourth Age, living in this kind of “community” can easily make you more socially isolated. Although the architecture and landscaping may be pleasing to the eye, the residents may or may not interact very much. This isn’t something you can normally spot from photographs or even on a tour. But a little feet-on-the-ground research should reveal how residents get around and how well they know each other.

The social life of a community is often revealed in its physical configuration. There is a saying in the field of geography: “The spatial is social, and the social is spatial.” The idea is that the configuration of a neighborhood affects the social relationships of the residents. The flip side is that the social relationships of the residents will in turn affect how they create and modify the spatial configuration of the neighborhood. Every community offers social clues:

• Are there sidewalks? Are there people walking on them?

• Are there courtyards or parks with benches? Are residents gathering and visiting there?

• Are there commercial establishments where people linger and socialize? Or do they just hurry in and out?

Such distinctions may not be a big deal for you in the early part of retirement, when you’re healthy, active, out and about in the world, and reveling in your new free time. But much later, when you may not be as active and may prefer to spend more time closer to home, this distinction could mean the difference between inconvenience and hardship, between a community that is livable and one that is not.

When the time comes, as it may, that you need assistance with the activities of daily living, would you prefer to continue living in your own home or move to a nursing home? (Surveys, over and over, overwhelmingly report that people want to “age in place.”)

Although this question deals with the Fourth Age, you should consider it as early as possible—right now, when you’re thinking about the Third Age. The decisions you make at this point will determine, far down the road, how long you can live in your own home. Will the home in which you choose to spend your retirement be one that allows you to live out your days there? (Hand in hand with choosing that home, of course, goes making every effort to preserve your health and physical self-sufficiency, the focus of another chapter in this book.)

At the middle layer of retirement geography—your community—the key concept is livability. At the micro layer—your residence—livability is the key concept, too. Just as you’ll spend more time in your community in retirement, you’ll also spend a lot more time in your residence than you ever have before. The question is not simply “How livable is it?” but also “How long will it be livable?” Based on what happens to you as you age, how easy or difficult will it be to live there? As you’re planning your retirement, you need to take the long view. The very long view.

Of course, even though many people claim that they want to age in place, not everyone wants to. Perhaps you imagine living in one residence for the Third Age when you’re vigorous and active, then moving to another residence for the Fourth Age when you can’t get around as well. That’s a perfectly good plan, if you really do that kind of two-stage planning. Just don’t ignore the Fourth Age because you find it unpleasant to think about. A little long-range planning now can save you (and your loved ones) a lot of frustration, work, money, and heartache down the road.

You may have been thinking of moving to a new home for your retirement, or not. Perhaps you’re definitely moving, because you want to downsize and get equity out of your home for retirement income. Perhaps you’re definitely not, because you have so many memories and friends (and so much stuff) associated with your home that you can’t imagine moving. In that case, if you need to draw equity out of your home for retirement income, you’ll look into a reverse mortgage or a home equity line of credit.

Perhaps you’ve hedged your bets by buying a vacation home that you plan to make into your retirement home. This will eventually lead to a sort of hybrid move, as you bring the remainder of your belongings to join those you’ve been keeping in the second home and adjust to living there as opposed to limited vacation visits. Perhaps you’re open to moving but aren’t sure yet what exactly you would be looking for, or whether a new home would be worth all the trouble. Whatever possibilities you’re considering, remember this: think both near term and long term. When you evaluate a residence—existing or contemplated—ask yourself two questions:

1. How well would that residence support your active early retirement life?

2. How well would that residence support your aging in place, later in retirement?

Let’s look at some examples of the active early part of retirement, in the Third Age. Think of people you know who have recently retired; you’ve probably noticed that they use their homes in variations on the following six basic approaches. As you read each description, consider it in light of your own chosen Ways to Live. How have you been using your home during your working life? Is that how you’d really like to use it in retirement?

1. Home as a Job. These folks retire from their regular job and, in effect, take on a new job as the caretaker, handyperson, and housekeeper of their own residence. They take personal responsibility for just about every aspect of maintenance. These hardworking folks throw themselves into duties for which they might previously have hired a professional (or a local teenager). Some retirees may find this truly rewarding; others may just be trying to keep busy, because they really don’t know what else to do with their time. Either way, handling physical and technical responsibilities helps keep us sharp as we age, so some of it may be a good thing for everyone. How about you?

2. Home as a Project. These folks use their newfound freedom (and sometimes their retirement money) to finally get to the major home improvements they’ve contemplated for years. Whether they use the do-it-yourself or have-it-done approach, it’s the focus of their interest and attention. If they’re not careful, the remodeling ideas can be leftovers, fitting their old life more than their new one. But ideally the ideas are fresh and relevant to the way they want to live in retirement. The improvements really increase quality of life. At some point, though, the home improvement phase must come to an end. That’s when these folks discover whether just living in their home is enough for their Retirement Well-Being. How about you?

3. Home as a Museum. These folks have accumulated a lot of physical possessions during their time in the second box, and their home is the place they display and store everything. Retirement is an opportunity to seek out and find even more of just the right stuff. Some people are true connoisseurs; others are true pack rats. For both, though, the thrill of acquiring more things or the sense of security in keeping them may be more important than the residence itself. Some may get involved as buyers or sellers at flea markets or in online auctions. The home may be just a warehouse or the ultimate display case, showing the entire collection. They may hope that their prized possessions will one day become family heirlooms. (If you’re such a collector, one of the best ways to test that hope against reality is to talk with your family about it. Really, really talk with them. You may find that they treasure the time spent with you more than they would treasure having your treasure.) How about you?

4. Home as a Community Center. These folks turn their residence into a setting for finally spending more time with other people. In Western society, life in the second box is typically time deprived, and social relationships often suffer. Some people use their additional free time in retirement to entertain—seriously entertain. They get friends and family into their home for large and small gatherings, and they encourage overnight guests whenever possible. Unlike the first two uses of a residence, this approach is focused less on the physical structure itself and more on its usefulness as a venue. Of course, if these folks have let their relationships slip away during the second box, they may be beyond reviving in the third box, regardless of the venue. How about you?

5. Home as a Base of Operations. These folks may not really be interested in their residence at all. They yearn to be somewhere else, traveling hither and yon. Whatever form their travels take, their home becomes more or less the base camp. These folks feel that they’ve been tied down long enough in the Second Age, and as long as they’ve got health and money, they’ll seek their happiness on the road. But consider this: Sooner or later we all must stop to rest, and rest becomes a bigger issue the further we progress toward the Fourth Age. At some point these folks will need to decide whether the residence they have is the one that they want to spend time in as their travels wind down. How about you?

6. Home as a Retreat. These folks may or may not be interested in their home per se, but they are interested in the privacy and serenity that it can provide. They may have found the requirements of the Second Age tiring, forcing them into more contact with the world than they really liked. Now they want to be left alone in peace and quiet and interact with the world on their own terms. Although home is a refuge even during the working years, it’s usually only for a few hours each day. The long, unbroken time structure of retirement certainly allows home owners to retreat if that’s what they want to do. However, as they move from the Third Age to the Fourth, a social support network will be an essential resource. The danger of residence as retreat is that unless the residents also emerge to keep relationships alive, those may not be there when they need them. How about you?

It all comes back to the essential message of this book: making plans for the life you want to live in retirement, then considering how your residence can support that life. Life planning comes first; residence planning comes second. This is really the foundation of your micro layer geographical decision. Only after you’re clear about your own Retirement Well-Being can you think clearly about whether you should stay put or go looking for your retirement dream home.

Thinking about what you’ll need in your residence in the later, aging-in-place phase of retirement is more straightforward than planning for the active early retirement years, because your options are narrower. The natural process of aging, even healthy aging, means that sooner or later it can become a challenge for you to live independently. However, you probably can’t foresee what your own specific challenges will be, when and if that time comes for you. There is a broad range of infirmities that become more common as you age, and you don’t get to choose them; they choose you. It may be a loss of strength or balance, physical dexterity, eyesight or hearing, cardio or respiratory capacity. If you knew in advance which infirmities might eventually force you to leave your home for some type of assisted living, you could plan better. You could make sure that the home you settle on, early in the Third Age, would be hospitable to the infirmities you expect to have later on. Your family genetics, your health history, any existing conditions, and your health habits are all factors, but these are far outweighed by the unpredictable. Seeing as you can’t accurately predict, it’s a good idea to consider some general ideas from the new concept of universal design (see the sidebar).

Universal design offers great guidance for planning the micro layer of your retirement geography. To look at your home with a universal design perspective means asking, “If someone with [fill in the limiting health condition] were going to live in this residence, what would allow them to be self-sufficient; what would make it a lifetime home?” Lifetime home is a new term to describe the residence that we hope will support us in both the early and the later parts of our retirement. It has a nice ring to it, don’t you think?

So what makes a home a lifetime home? Mostly, that it can accommodate your changing needs. It can be as simple and easy as adding sturdy handrails in bathrooms, or more complex and expensive, such as installing lower counters and cabinets or a chair lift on a stairway. But some livability fixes can be almost impossible to implement in the layout of many homes. For example, if rooms are on multiple levels—even if they’re separated by just one or two stairs—there may not be space for a wheelchair-accessible ramp.

Thinking about your physical needs as you age may be something you’d prefer to put off. And even when you do address the issue, you don’t have a crystal ball. But evaluating your residence now with these ideas in mind could eventually make the difference between continuing to live there and being forced to leave.

Your inner experience of your retirement geography is as important as the outer layers that we’ve already explored. Sense of place is that connection you feel to a particular place, your emotional reaction to it, the symbolic meaning that it has for you. Sense of place is not easy to pin down, because it is something different for each of us. It has to do with how unique or generic a place is, how personal or impersonal.

This idea has arisen in the context of sweeping changes in the way we live in Western society. Many people are uncomfortably aware of the sameness, the lack of authenticity, the placelessness that has proliferated across the country. Subdivisions filled with look-alike houses, business parks filled with work-alike offices, interspersed with standard-issue strip malls. National chains driving out local retailers and franchises replacing family-owned restaurants. Places that once had a distinctive local character are being made over to fit into the same mold. There are parts of many cities that look just like parts of any other city. And they don’t just look the same—they feel the same. It’s difficult, if not impossible, to have a sense of place in such environments. Of course, many jobs are geographically connected to them, and in your working years you may need to live there. However, retirement offers your greatest geographic freedom. Are you curious where you might discover your own personal sense of place?

Sense of place ranges from the universal to the personal. Certain landscapes evoke a strong sense of place for just about everyone. You have surely visited some unfamiliar places that you felt an immediate connection with—the mountains, the seashore, a deep forest, green rolling hills, the desert in bloom. You could say that those locations have a universal sense of place, and most humans would probably agree.

You have surely visited other places to which you felt a culturally based connection—for example, a classic Main Street in a small town, a setting that resonates with your childhood and the image presented in your schoolbooks and in magazines. Many people who share your upbringing would experience the same sense of place.

Finally, there are places that you connect with because of your own personal life experience; you would not expect others necessarily to experience the same sense of place that you do. You may have lived there in the past or dreamed about living there in the future. You may have gone to school there or vacationed or visited relatives there. Or you may have never set eyes on the place before, but once you do, you say, “This is the place.” For your retirement geography, your own personal sense of place is the one that matters most.

You can’t predict what will create that sense of place for you. You can’t tell from pictures or descriptions alone. You can’t tell from what other people say about it. You certainly can’t tell from the statistics about it. No, sense of place comes from direct experience. It could be the evident features of a place: its climate, topography, vegetation, or architecture. It could be the people you interact with there. It could be what you know about its history or its importance in the larger scheme of things. It could be your own personal memories, distinct from your current experience of the place. You may even get the sense that a particular place will support your chosen Ways to Live.

The only way to really know whether a location has a sense of place for you is to become an explorer; you need to be there and experience it. You may need to move to a new place, or you may instead need to see the place you live now as if for the first time. Only you can explore the geography of your Ideal Retirement. But it’s worth exploring, because your retirement will last a very long time, if all goes as you hope.

Two factors that are critical to just how long it will last are the biology and medicine elements that make up the health dimension of your Retirement Well-Being, which is the focus of another chapter. In this chapter, as we’ve explored where you might spend your retirement, we have frequently touched on the need to plan for both the natural aging process and the unpredictable infirmities that may arise. It’s wise to choose a livable community and a home that incorporates universal design to support your aging in place. Having done that, you’ll want to do all you can to preserve your physical vigor and independence for as long as possible.

But first, you get to brainstorm the geography of your Retirement Well-Being.

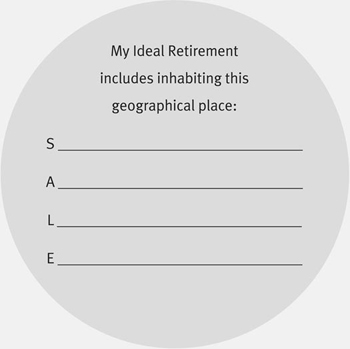

You’ve used the Four Layers of Retirement Geography to imagine the kinds of places that could best support all the other elements of your Retirement Well-Being. You should now have plenty of raw material for your final geography exercise: identifying the geographical element of your Ideal Retirement. That place could be the one you’re living in now or someplace new.

You can approach the four layers in any order that makes sense for you. The acronym SALE doesn’t mean you need to sell your home; it’s just a way to help remember the layers.

If it’s earlier in your career, you can note just the broad or general features of each layer. If it’s later in your career, you should be more specific. If you’re approaching retirement, you may have all the particulars completely worked out.

My Sense of Place: The Inner Layer

What places could create a particular feeling or a sense of connection for you in retirement? These might have a sense of place on a universal, cultural, or personal level, or be especially symbolic or meaningful for you. Think of places you’ve already experienced and ones you would like to explore. Write the names of several types of places, or specific places, for this layer, for example, “Ocean shore; Colorado Rockies; Taos, New Mexico.”

My Aging-in-Place Residence: The Micro Layer

What role will your residence play in your retirement? Is it likely to become a job, a project, a museum, a community center, a base of operations, a retreat, or something else? To fill that role, what physical features would your home need? Financially, would your home be a significant expense, a low-cost place to live, or a source of income? Would your residence accommodate aging in place, or do you plan to move as you get older? If it’s early in your career, identify a general type of residence (such as a city apartment, resort-style condo, or country house). If it’s later in your career, try to identify a specific type of residence, or even a specific house (say, in your town, seen on vacation, or found on the Internet).

My Livable Community: The Middle Layer

Considering how far into retirement you plan to live there, how supportive does your community need to be at different stages? Which livability issues are most crucial to you? A walkable neighborhood? Access to medical care and other services? Transportation? Social interaction? Activities? A retirement-age population or one that’s age-integrated? What other features or amenities are most important for you? Financially, will your community provide opportunities to upscale or to economize?

My Essential Region: The Macro Layer

Which part of the country offers what’s most important to you? Could it involve the people you have relationships with? The opportunity to connect with your interests, strengths, or values? A supportive environment for your health or health care? A lower cost of living? Where are the things that you absolutely wouldn’t want to live without? Is it likely your essential region will change during your retirement years?

Now go back to your responses for all four layers and choose the most appealing or significant responses for each layer. (These aren’t set in stone; you can revisit and revise your choices later as your planning evolves.) Enter these on the appropriate lines of your Life Circle to use for your One Piece of Paper in chapter eleven.

“It’s not a health care system at all; it’s a disease management system.”

—Dr. ANDREW WEIL, integrative medicine pioneer