CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 2 CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 2Nucor, America’s biggest steel company by market value, has transformed the steel industry by focusing on “mini-mill” steel production, using scrap steel as its raw material. Mini-mills once actually were small steel mills designed for economic production of customized orders, often using more advanced technology than the industry giants. Nucor seized on the mini-mill model of flexible, low-cost, high-quality steelmaking and drove it to automobile-production scale. Last year, its US production was nearly thirty million tons from twenty-three mills, and it is the dominant American structural steel provider, with profit ratios double those of the big traditional companies. It is also one of the very few large employers that made no layoffs during the financial crash, and it still operated profitably throughout the downcycle.1

Its continued growth, however, has been threatened by rising prices of quality scrap steel as more and more companies adopted Nucor’s technology, and so it set a company goal of finding seven million tons of high-quality, affordable, scrap substitutes. Nucor could buy and convert pig iron to steel, but was uneasy with the volatility of merchant pig prices. Building blast furnaces to smelt its own iron from ore was another alternative, but to be cost-effective, blast furnaces must be very large and operate more or less continuously, while Nucor’s business strategy is all about fast adaptation and flexible production schedules. Blast furnaces also match up poorly with Nucor’s image as one of the world’s “greenest” steel companies. Another solution was “direct reduced iron” (DRI) a method of melting iron ore and separating out the slag in an electric furnace similar to the ones used to melt scrap. But melting ore requires a lot of energy, and since the preferred DRI processes are gas-fueled, high American gas prices made the idea impractical. Until now.

In late 2012, Nucor announced a long-term investment and supply deal with Encana, a Canadian shale player that Nucor credits with attitudes similar to its own toward safety, employees, and the environment. Nucor committed to spend $3.6 billion to capitalize Encana’s expansion of its natural gas properties in return for a 50 percent working interest in the resulting wells. Normally, a 50 percent working interest arrangement confers the right to take half the profits from the wells, but in this instance Nucor will take half the gas at a cost-based price. The volumes contemplated should give Nucor sufficient gas to fuel two large DRI plants in Louisiana—the first of which will open this year—plus all its steel operations. Nucor is a global company with operations around the world, but has so far maintained almost all of its manufacturing in the United States, and the DRI strategy will be a big factor in allowing them to stay that course.

The benefit for Encana is at least as great. Encana’s initial development was tilted emphatically toward shale gas, both in Canada and the United States. But the temporary glut in American natural gas that drove prices to unheard-of lows (in 2012 down to less than $2 per thousand cubic feet [Mcf], which hardly meets the cost of production; on a barrel of oil equivalent basis, it is close to $12 crude) required that the company’s oil and gas assets be written down to reflect the fall in their value. Gas-heavy companies have taken big hits to their asset positions. Those are non-cash charges, but banks don’t lend open-handedly to companies with declining net worth, especially if the companies are aiming to expand gas production. Like other exploration and production (E&P) companies, Encana has been switching its production to liquids, but its holdings are not as liquid-rich as those of some others. The Nucor deal has given it the wherewithal to maintain an active drilling program in the Colorado’s promising Piceance Basin.

The deal may well be a prototype for other companies. Fears of yo-yoing gas prices have a real basis, and gas investors have been battered over the past couple of years, although as this is written in early 2013, prices have recovered to about $3.50, closer to the $4–$6 range that most observers feel is a healthy median. The very low recent prices should be a temporary phenomenon, caused by the mismatch between the gas production boom and the limited transport capacity out of the shale regions. Many producers have shut down their gas wells—they are fairly easy to restart—and are supplying their customers from stored gas. As the gas glut is worked down and the multiple new pipeline projects come on line, prices should stabilize. But it may be a while before investors can be enticed to take a new plunge into gas plays.

The Nucor story is just one example of the spinoff effects of abundant, cheaper energy. A number of major industries—aluminum, chemicals, iron and steel, paper—have energy costs that are significant percentages of their sales. In aluminum and chemicals, energy consumes 5–6 percent of total revenues. US chemicals production is about $1.5 trillion, so a wholesale shift to much less expensive natural gas would produce tens of billions of dollars of profits.

The impact of cheaper energy on American manufacturing will be all the more powerful since it comes on top of a broader momentum to bring much of our offshored production back home for other reasons—“reshoring” is a voguish term at the business schools. Peoples throughout south and east Asia are widely achieving middle class lifestyles, and they want better pay and benefits, shorter workweeks, and some of the other perquisites that their Western peers enjoy. The “low-cost” label customarily applied to places like China and India is out-of-date.

At the same time, American production costs have mostly been falling, especially after the ruthless cost-cutting that companies employed after the 2008 crash. America may never produce hard goods as cheaply as China, but the cost convergence spotlights the embedded inefficiencies of offshoring. Inventory controls are compromised when goods spend weeks on ships. Distant contracted production necessarily increases the challenge of quality control—it’s harder to make rapid design changes or to react to customer complaints. A big American energy cost advantage can be the last piece of the equation that tilts the decision toward reshoring.

To begin with, energy by itself generates lots of jobs without taking account of the productivity jolt it gives to other industries. IHS is a global consulting firm with a major practice in energy. (Daniel Yergin, one of the world’s leading academic authorities on energy is a vice chairman of the company.) In the fall of 2012, the company published an analysis of the economics of the unconventional oil and gas sectors using models developed by IHS Global Insight, their country intelligence and economic forecasting business.2

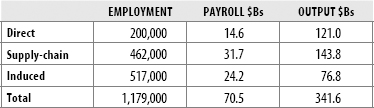

Their estimates of the employment impact are in Table 2-1. Those numbers are built from three estimates: first, the direct employment in the unconventional energy industry—geologists, rig and equipment operators, mechanics, laborers, and the like; second, the employment in their supply chain—a typical well requires up to one hundred tons of high-quality steel pipe, fleets of trucks and trailers, a small hangar full of earthmoving, drilling, and other equipment, some very high-end seismic and imaging gear, as well as chemicals, special sands and other supplies; and finally the “induced employment” generated by the new spending by both the direct and supply chain workers. The numbers in Table 2-1 are premised on the assumption of a steady expansion of unconventional production, and a rising pace of opening new wells—this in an industry that, for all practical purposes, didn’t exist a decade or so ago.

TABLE 2-1: Unconventional Oil & Gas Employment

Note that supply-chain employment growth is greater than the growth in direct employment. One of the bullish features of the industry is that for the moment, it is a US specialty, and the technology and supplier know-how has a pronounced made-in-America stamp. China has very large shale deposits that may be more technically challenging than the primary American sites, and while its government is anxious to jump-start a home shale industry, they freely concede that they will need Western help to do so. In 2009, the United States and China launched the US–China Shale Gas Resource Initiative to ensure close contact as the industries evolve. Chinese companies have been permitted by both governments to take minority positions in American companies, and a few Western companies, like Schlumberger, the giant oil field servicer, have been acquiring stakes in Chinese firms. Schlumberger, technically a Curaçao firm, is a truly global company with principal offices in Paris and The Hague, but with its primary headquarters in Houston. It is a major operator of US unconventional drilling and production sites. Necessarily, the suppliers for that business are primarily American companies. China, as always, will be anxious to insource its supply requirements as soon as possible, and will doubtless quickly supply its own pipes and excavators, but insourcing the most sophisticated equipment and the skills to use it is likely to take a decade or more.3

TABLE 2-2: Annual Upstream Capital Expenditure

* Cumulative spending over the entire period.

Also note that IHS analysts calculated just the employment from upstream components of the unconventional energy rollout over the next couple of decades. Upstream processes include drilling, completion (fracturing and starting the upflow of oil or gas), facilities construction, and gathering (sending the product via pipeline to a local hub). Table 2-2 estimates upstream capital spending.

Midstream processes include pipeline and other transportation from local hubs and usually further processing, while downstream processes cover the complex refinery processes, and marketing and transportation to end customers.

All oil products, and most NGLs (natural gas liquids) and other condensates require refining, usually by catalytic cracking. The United States had substantial excess refining capacity when the unconventional boom got underway, left over from the days when it was one the world’s largest conventional oil producers. That is now being used up and requires substantial modernization. Very pure dry gas, of the kind normally found in the Marcellus shale, often requires only a washing and filtering before it is “pipeline ready,” which is usually handled in the upstream phase. Exporting gas, however, will require multi-billion-dollar liquefaction facilities.

Transportation is typically by pipeline. The United States already has an extensive pipeline network, but industry experts suggest that for the foreseeable future it must add at least 2,000 miles a year both to accommodate product volume, and to make connections with new producing areas. The ongoing imbalance between production and transportation is behind a small economic tragedy unfolding at the Bakken shale in North Dakota and Montana. The Bakken is primarily an oil play, and its gathering and transportation systems are oriented to petroleum refineries. But its oil deposits typically come with large quantities of “associated” natural gas. Since the Bakken lacks gas transport and processing capacity, it is flared.*

Wages in the industry are quite good by today’s standards. First-line supervisors and skilled and semiskilled workers at the rig sites are typically paid in the $20–$33 per hour range. Overtime that is built into the standard work schedules has resulted in very young workers taking home gross pay in the $100,000 a year range, with better than average benefits.

There is a downside to the good pay, since the drilling sites are often in quite remote parts of the country. The boom in thinly populated North Dakota has resulted in large temporary settlements of single men with associated problems of alcohol, violence, and sexual assaults. Companies appear to be addressing such issues haphazardly at best. By no means are all wells in remote areas, however. Some of the most productive wells in the country are spotted throughout the Dallas-Fort Worth airport, and virtually surround Fort Worth to the west. The lateral from one well is said to terminate under the Texas Christian University football stadium. The workers at the Devon sites, I was told, nearly all lived within reasonable driving distance of their work location.

Organic chemistry deals with carbon-based compounds, usually with carbon-hydrogen bonds—the same hydrocarbons that we use for fuel. The industry’s base products include plastics, vinyl chloride, polyethylene, and poly vinyl chloride (PVC), among others; its end-use products include Styro-foam, tires, sealants, adhesives, films, liquid crystal screens, and a vast range of fibers like nylon and polyesters—in short, a huge portion of the things that we depend on for daily living. The organic chemical industry is therefore a massive user of hydrocarbons, first as the raw material, or feedstock, for its plants, and second to generate the heat and pressures for the giant “crackers” that break the hydrocarbon molecules into smaller chains for reassembly. It consumes hydrocarbons for feedstock and fuel in roughly equal volumes.4

Natural gas was abundant in America even after American oil production began its swoon in the 1970s, and the feedstock favored by American chemical plants was ethane, the lightest of the natural gas liquids (it’s usually a gas in the atmosphere). The European industry favored naphtha, derived from petroleum. It is a more complex compound, but can be cracked and reassembled into the same products that Americans constructed from ethane. As a general rule, the American industry was very competitive so long as the price of a barrel of oil was about seven times the price of natural gas at the Henry Hub, a gas distribution focal point in Louisiana that is the pricing point for natural gas futures contracts.*

The American industry did very well in the first part of the 1970s. The country still had plenty of gas, and oil prices were soaring—to more than twenty-two times the price of gas. But as gas supplies dwindled, the cost advantage steadily eroded. American plants made a brief recovery in the 1990s, due to the oil price disruptions of the Gulf War, but when the government encouraged electrical utilities to shift to gas through the later 1990s, gas prices jumped with devastating effect on the chemical industry—until shale gas burst on the scene in volume around 2002. Over the last several years, the industry has been recovering strongly. By 2010, the United States was one of the most competitive countries in the world for organic chemicals, with plants running full, and exports up and rising.

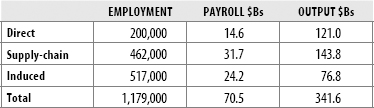

Economists at the American Chemistry Council (ACC) have generalized from their industry’s experience to assess the effect of the shale gas bounty on eight energy-intensive industries.5 Ranked in order of total energy usage, they are chemicals (excluding pharmaceuticals), plastic and rubber products, fabricated metal products, iron and steel, paper, aluminum, and foundries.

Using econometric models similar to those used by the IHS analysts, the ACC’s analysts projected the additional annual employment and GDP generated by lower fuel prices by 2017:

TABLE 2-3: Economic Impact in Eight Industries

Those are serious numbers. The $342 billion total output effect is about 2 percent of GDP for the United States. And note that these data comprise only these eight industries, so they omit the gains in the energy industry itself, which was the focus of the IHS study. In normal times, rapid growth in one sector would be managed in substantial part by shifting workers and resources from other, less favored sectors. But the Great Recession has left so much slack in the economy, most of this should be additive.

There are a number of other analyses that coalesce around similar numbers. A detailed 2012 Citigroup study suggested that the cumulative effect of the energy revolution would be 2.2–3.6 million net new jobs by 2020.6 That is quite close to the combined estimates of the IHS and ACC studies, which between them covered the economic impact from the growth in both the energy and biggest energy-using industries. (At the high end, that would increase total employment by about 2.5 percent.) Dow Chemical has recently listed 108 major industrial projects planned, announced, or already underway by energy-intensive manufacturers, thirty-three of them with 2012 or 2013 start dates and sixty-two with start dates by 2015. The total planned investment, just in these projects, is estimated at $95 billion.7

Activity on the ground reported by the consultancy PWC supports the bullishness of the forecasts. Dow itself restarted a long-mothballed ethylene plant unit in Louisiana in January of 2013; the company is also planning to open a new ethylene unit on the Gulf Coast in 2017, to build out more capacity in existing facilities in Louisiana and Texas, and to build a new Texas propylene plant, all in the near term. Formosa Plastics is planning a $1.5 billion expansion program in Texas, and Westlake Chemical is expanding its ethylene capacity in Louisiana and considering another unit in Kentucky. Chevron Phillips and Bayer are scouting sites for new ethylene capacity both on the Gulf Coast and in the Marcellus. Shell has settled on the site for a major new ethylene plant near Pittsburgh. US Steel, the pipemaker TMK IPSCO, and the French steel company Vallourec, are adding capacity and building new plants in the shale regions to supply the pipe and other equipment needed by the producers, as is Voestalpine, a major Austrian steelmaker. US Steel is also exploring substituting natural gas for coke in some of its processes, which it estimates could save it about 1 percent of its production costs—no small amount in the tightly competitive global steel game. Perhaps the biggest commitment of all is the announcement that SASol, a South African specialist in gas-to-liquids (GTL) conversion, a tricky and controversial method of converting lighter gases into higher value products like diesel and gasoline, is planning a $14 billion GTL facility in Louisiana. GTL is an expensive process, and SASol will require a long period of low gas prices to make the investment pay off, but the company seems confident it can pull it off.8

Over the past two years, the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) has published a series of studies on the emerging recovery of American manufacturing. Although they count falling US energy prices as a positive factor, they are not the linchpin of the thesis. BCG’s argument, rather, is that productivity-adjusted Chinese and American labor costs are rapidly converging, even as the US matches up well against China in the costs of many other factors of production, like land, transportation, and the cost of equipment. By 2015 or so, BCG estimates, an American company will save only about 10–15 percent of costs by manufacturing a kitchen appliance in China, which is too little to justify the long delivery lead times and other aggravations that come with offshoring.9

China’s rise as a global manufacturing power has been extraordinary. In just the nine years from 2000, China’s exports leaped fivefold, and its share of global exports increased by two and a half times. And it happened nearly across the board, in a wide range of industries. Its share of global exports in textiles, furniture, ships, telecom equipment, office machines, and computers all rose into the 20–33 percent range. The United States clearly bore the brunt of that onslaught. In the first decade of the 2000s, America lost 6 million manufacturing jobs—in the mild recession year of 2001, the country lost 1.5 million manufacturing jobs, far more than even the 900,000 jobs lost in 2009, the worst year of the Great Recession. The reasons the initial impact was so severe include, among others, America’s commitment to a normal trade relation with China,10 the convenient sea-lanes and the well-developed West coast container ports, and the binge of consumer credit creation by the Greenspan Federal Reserve. By the midpoint of the decade, however, it was clear that Chinese exporting prowess was being felt everywhere—in western Europe, in the rest of Asia, in Latin America, and in Africa.

But as a wise man once said, unsustainable trends tend not to be sustained. China’s great success and the extraordinary achievements of its workers in moving up the technology curve are turning it into a middle-class nation. Chinese worker productivity is still growing at about 8 percent a year, an extraordinary rate, but worker compensation is growing more than twice as fast. In 2000, average worker compensation in the Yangtze delta, one of China’s most dynamic manufacturing areas, was about $0.72 an hour. By 2010, it had risen to $8.62, adjusted for productivity. That’s still a lot less than the $21.25 averaged by manufacturing workers in the American South in 2010. But labor is only a part, often a small part, of the total cost of product, and when you consider America’s competitiveness in so many other factors of production, a modest wage differential is not enough to drive business offshore. The BCG analysts project that, by 2015, total wages in the Yangtze delta will be up to $15.03 an hour compared to $24.81 in the American South—which is parity, for all practical purposes. Wages in India are on a similar course. Other Asian countries further down the development curve, like Vietnam and Bangladesh, have very low wages, but are not nearly as sophisticated or as productive as China, and are unlikely to repeat the Chinese experience, at least not in so compressed a time.

The loss of American manufacturing has never been as catastrophic as it sometimes feels. At the end of World War II, the United States accounted for some 40 percent of global manufacturing production. From such lofty heights, there was nowhere to go but down. It took a generation for Europe and Asia to recover from the war’s devastation, while the United States grew fat and lazy as the world’s richest-ever hegemon. That era came to an end when the Germans, Japanese, and Koreans launched an all-out assault on American automobile, consumer electronics, and computer and chip markets. After a violent restructuring in the 1980s, the United States emerged as the market leader in most high-value-added industries, like microchips, aerospace, and pharmaceuticals. By the close of the 1990s, it was once more the global “hyperpower,” before it was kneecapped by inconclusive foreign wars, the Chinese trade onslaught, and the housing bubble and related misdeeds of its financial sector. Despite all that, inflation-adjusted American value-add in manufacturing actually increased by a third to $1.65 trillion between 1997 and 2008, just before the recession. The collapse in US manufacturing was in employment, not in output, but falling employment is always the flip side of a highly productive industry.

Among advanced countries, the United States was clearly an outlier in the degree that its workers bore the brunt of the financial crash. One of the anomalies of the recession was how corporate profits held up even as sales plummeted. Lavish federal bailouts made 2009 one of Wall Street’s most profitable years, while the ordinary people who lost their jobs and homes by the millions could fall back only on the least generous social safety net among the major industrial countries. Companies laid off workers well ahead of sales downturns, and single-mindedly focused expenditures on labor-saving equipment. Unattractive and unfair as the process was, the restructuring has made the United States one of the most desirable manufacturing sites in the world, especially in states like Virginia, Tennessee, Georgia, the Carolinas, and Alabama, where land, labor, and energy is cheap and factory productivity is very high. Just within the past year, Japanese and Korean automobile companies have been adding to their American plants, or building new ones, in order to service the European market; Siemens has begun producing gas turbines in Virginia for export to Saudi Arabia; and Rolls-Royce has opened an airplane parts plant to serve its global customers.

The BCG analysts estimate that the United States’ total cost advantage over Japan and Europe is in the 25–45 percent range, even as it offers one of the world’s best trade logistics capabilities.* They also identify seven American industries that are on the economic tipping point of a substantial reshoring. They are: computers and electronics; appliances and electrical equipment; machinery; furniture; fabricated metals; plastics and rubber; and transportation goods (meaning primarily the components industry). Collectively, they account for well over 10 percent of American consumption. The reshoring opportunity, BCG estimates, coupled with the parallel gains in exports, should shave $100 billion off the trade deficit by 2015—in addition to the shrinking deficit in energy trade. The “global imbalances” so deplored by global financial authorities over the past decade or so may shrink away far faster than anyone expected.

The case for an American manufacturing renaissance, therefore, is not dependent on the new availability of inexpensive fuel and feedstock. A major revival is quite likely in the works anyway, but the energy bonus will help enormously in getting it off the ground.

How much we actually realize those benefits, however, may turn, at least in part, on a question that has shadowed all of the economic projections: Assuming the energy boom is real, can America maintain its energy price advantage? The industry likes to think of the world’s energy supply as a bathtub—you take something out or put something in, and the level in the whole tub rises or falls. But at the moment at least, natural gas clearly doesn’t work that way. North America currently has a gas glut and rock-bottom prices. Europe gets most of its gas from Russia, which prices it by reference to the cost of oil, or about triple what Americans pay for gas. East Asia, especially Japan and Korea, pony up four or five times American prices; they are energy-poor—the Fukushima disaster has left Japan in desperate straits—and they must be supplied by tanker, which is expensive.

The US gas industry has mounted an all-court press to convince the government to allow the export of natural gas. Economic theory is on their side. Prices set by willing sellers and willing buyers in open markets are always the fairest and the most market-efficient. So if energy product could move seamlessly to the best market, quantities of gas and of petroleum with the same energy values would be priced approximately the same—the price of gas and the price of oil would become linked. The increase in efficiency would allow all the world’s consumers to pay slightly less for energy. American gas companies, and especially the largest players like Exxon-Mobil and Shell that are best positioned to trade globally, would get a nice profit jump. But achieving a higher state of global efficiency would not do much for the American economic revival that the oil and gas industry has been trumpeting as their gift to the nation.

It’s a complicated issue, and I will try to unpack the main questions here. By law, companies must secure permits from the Department of Energy (DOE) before exporting natural gas. Export permits may not be denied for sales to countries with a free trade agreement (FTA), of which there are only three with a major interest in importing gas. Canada and Mexico, which are covered by President Clinton’s 1994 NAFTA treaty, have long had gas pipeline connections with the United States, with flows in both directions. The newest free trade partner, South Korea, is eager to tap into cheap American gas. As of this writing, twenty-three companies have filed gas export permit requests, only one of which, from Cheniere Energy, has been approved for general exporting from a facility that will go into operation in 2015 on the Gulf Coast of Louisiana.11

It is not easy to export natural gas. It must first be highly purified and then liquefied (LNG for liquefied natural gas). At negative 162°C, natural gas becomes a liquid with about 1/600 the volume of normal gas, and an energy density close enough to conventional oil products that it is cost-effective to ship. The importing country requires a re-gasification plant of similar complexity. LNG plants and re-gasification plants, both cost billions and take years to build. In the late 1990s, as American sources of natural gas dried up, prices spiked above $60/Mcf, and American companies rushed to build re-gasification plants to import LNG. Forty-seven plants were approved and a number were built at a total cost estimated in the $100 billion range. All of them were mothballed by the shale gas boom. The Cheniere LNG plant will be a converted re-gasification facility; much of the infrastructure—pipelines, harbor work, storage facilities—is already in place. But it will still cost $5.6 billion to convert and will not be operative until 2015, at an initial shipping capacity of 2.2 billion cubic feet/day, roughly equivalent to 117 million barrels of oil a year. Greenfield plants are much more expensive. ExxonMobil is the lead partner on a Papua New Guinea LNG plant: at the 70 percent completion stage in the fall of 2012, the company announced a $3.3 billion cost overrun, bringing the total anticipated cost to $19 billion. In short, these are all high-rolling, high-risk projects.12

Economists, by and large, have weighed in almost unanimously in favor of unrestricted exporting, and suggest that it would have little impact on domestic US prices. But virtually every study assumes a high elasticity of gas supply. A study by a Rice University economics institute assumes that every unit of additional gas demand will elicit one and half units of new supply.13 That is plausible if the bullish projections for recoverable natural gas reserves are true, and they may well be. But only about 10 percent of “technologically recoverable reserves,” are actually “proven reserves”—the rest are projections. If it should happen that maintaining supply growth will require tackling more challenging and less accessible fields than we are exploiting now, or environmental challenges succeed in curtailing production significantly, prices could change quickly.

Pressures to approve unlimited LNG exporting built rapidly in 2012. The DOE commissioned an economic analysis of the domestic price impact from a private firm, NERA Economic Consulting, Inc., which was released in December 2012. Wall Street, the industry, and its Congressional minions greeted the report with hosannas, for its overall conclusion, after examining a number of exporting scenarios was that:

The U.S. was projected to gain net economic benefits from allowing LNG exports. Moreover, for every one of the market scenarios examined, net economic benefits increased as the level of LNG exports increased. In particular, scenarios with unlimited exports always had the higher net economic benefits. . . . Natural gas price changes attributable to LNG exports remain in a relatively narrow range across the entire range of scenarios.14

Predictably, a small flood of exporting permit requests are arriving at the DOE, and a large Congressional cross-party alliance is developing to sponsor legislation removing any bars to exporting. The report ringingly concludes that exporting will not cause gas prices to be linked to world oil prices. But the reason NERA adduces for the low price effects is that if the United States began to export gas, lower-cost suppliers, like Russia, Qatar, and possibly Australia, would immediately undercut American prices and limit its export penetration to quite modest levels. If the industry actually believed that, it would be insane to waste untold billions on LNG plants. In fact, judging by trade journal speculations on the vast opportunities on the entire Asian continent, the industry is envisioning a gas export boom.

The industry drumbeat for maximum exports suggests that they really believe they can penetrate Asian and European markets at only a modest discount from current prices in those territories, which would give them a “netback,” or revenue after the substantial additional costs of liquefaction, shipping, and de-gasification, that would be far higher than they could earn at home. And if that were the case, they would inevitably raise domestic prices to at least the netback level, which will plausibly be high enough to sink the manufacturing revival. Some members of Congress, like Senator Lisa Murkowski (a Republican from Arkansas) even invoke quasi-moral grounds for exporting, since we “owe it to our allies.”

If the NERA report is right, the very precariousness of the prospects of successful exports is reason enough to hold up permits. Earning back the cost of an LNG plant takes up to twenty years. Rushing to build them by the dozen may be courting the same order of investment calamity as the rush to build the re-gasification plants. The companies are also mostly the same ones, trawling financial markets for more tens of billions in the hope of recovering some of the tens of billions lost the first time around.15

But there is no reason to take the NERA report as dispositive on anything, for it is a glib and blindered exercise—mechanical modeling carried out by robot economists. For example, the benefits were calculated merely by comparing the value of new export revenues against the higher gas costs imposed on the rest of the US economy. Since it was assumed that companies wouldn’t export unless they received higher returns than at home, that number was necessarily positive. It simply dismissed out of hand the collateral gains from the rebound in manufacturing that so many economists anticipate from the drop in energy prices.

The report is also remarkably tone-deaf. Although it acknowledges that under all export scenarios, “wage income decreases in all industrial sectors except for the natural gas sector,” it happily concludes that such effects are offset by higher export revenues and additional income to “consumers who are owners of liquefaction plants.”16

Fortunately, as the drive for unrestricted gas exporting was developing last year, a group of large manufacturing companies, led by Dow Chemical and Nucor, among others, formed a counterlobby, America’s Energy Advantage (AEA), to slow it down. The economists at Dow Chemical prepared a blistering refutation of the NERA report, which was submitted as part of the record of hearings held on the issue by the DOE in January 2013.17 Some high points, drawn primarily from the Dow paper, are:

• The NERA report relies on 2009 data from the US Energy Information Agency (EIA), but at almost the same time as the report was released, the EIA virtually doubled its projected rate of growth in domestic gas demand, precisely because of rising manufactures.

• The pipeline requirements for exports do not match up well with those for domestic manufacturers. Just by authorizing the export expansion, the government will trigger an anticipatory shift in pipeline investment that will further disadvantage domestic companies. In such an environment, companies sponsoring new investment would be almost obligated to pull back from their programs.

• The report assumes virtually unlimited natural gas production capacity, which is questionable. Even if the gas is there and readily recoverable, successful legal actions by environmentalists may succeed in greatly lowering actual production.

• The argument that exporting will not drive up gas prices rests on the assumption that the free market will force American competitors, like Russia, to drive their prices down. But gas contracts are usually contracted on a long-term reference price basis, with little scope for market-based adjustments. Beyond that, international hydrocarbon markets have long been cartel-driven, and American oil majors have learned to live comfortably within cartel-dominated pricing regimes. Indeed, an OPEC-like organization of gas-producing nations has been organizing to create just such a regime.

• The report dismissed energy-intensive industries as “low-margin industries,” as if they produced little economic value. In fact, all heavy manufacturing firms do have lower margins than, say, software and finance. But that’s because they have such large employment multipliers. Their margins are lower because of their heavy supply chain and capital goods requirements, which reverberate through the entire economy.

• The notion that export profits would be returned to American “households” is absurd. In the first place, a large number of the companies participating in the shale plays are foreign—from China, France, England, Norway, the Netherlands, Australia, and some of unknown origin—and their markups will go to their own shareholders. In addition, global companies like Shell and ExxonMobil, although they are headquartered in the United States, invest globally, wherever they can get the highest return. There is no guarantee that their foreign revenues will be recycled back to the United States.

In fact, there is a real-life case that suggests that NERA’s and other conventional economic analyses are simply wrong. Australia has long been involved with natural gas and LNG exporting, but regulatory responsibility has been delegated to two different authorities, for western and eastern Australia respectively. The two took different approaches, and so present a fine natural experiment. The western authorities designated specific reservations of gas that could not be exported in order to service local industry at cost-based prices. The eastern authorities permitted LNG exporting without any such protections. A detailed study published in October 2012 by the National Institute of Economics and Industry Research, found that, while the western scheme worked more as less as planned, the results in the east were radically different. In the east, as soon as LNG projects neared production, long-term domestic supply contracts “evaporated” as suppliers built stocks for export. Long-time customers were left to compete for surplus gas left over from selling into the east Asian markets. Naturally, the surplus was then available at east Asian prices, the highest in the world, less transport costs. The linkage is quite explicit. Taking into account the decline in competitiveness and employment of the gas-dependent eastern companies, and the negative multiplier effects within the rest of Australia, the Institute calculated that the country loses $24 in economic output for every $1 of gas exports.18

In any case, the idea of oilmen extolling the virtues of free-market pricing is oxymoronic. In January 2013, the London Centre for Global Energy Studies (CGES) released a detailed study of the costs of oil production throughout the world. About a third of world oil supply costs less than $10 per barrel and nearly 90 percent costs less than $20 per barrel. On an energy equivalent basis, $20 per barrel is about the same as the cost of producing Marcellus shale gas. So why did the average price of oil hover near the $150 mark for much of the last decade? Partly, no doubt, because of fears of war-related supply disruptions. But the primary reason is that international oil prices are determined by the budget requirements of the oil sheikdoms, with the willing, doubtless delighted, collaboration of their cartel partners like ExxonMobil and Shell. For six of the last eight years—every year except for those during the Great Recession—ExxonMobil earned more than $40 billion in profits. As the CGES study suggests, those earnings were generated by pricing power, not cost management.

Let’s fill in the rest of the boxes. Why are American natural gas prices so low? Because transport limitations have created an anomalous pricing pocket beyond the umbrella of the cartel. And why are American oil and gas executives pushing so hard for LNG exports, even though the NERA analysis suggests that the opportunity is rather modest? Perhaps the alluring shade under that cartelized pricing umbrella has something to do with it.

The Obama administration has generally been quite cordial to the energy industries. As an old-fashioned liberal who has long lamented the loss of stable blue-collar jobs, I have been glad to see that stance. The tactic has required hewing a middle path between the demands of the environmental and energy lobbies—basically, letting the industry grow while insisting on reasonably attainable environmental standards. Giving the industry its way on this one, however, could completely destroy our best hope in a long time of a broad, middle-class-based economic recovery.

The good news is that there is time. The AEA lobbying, judging by the reactions at the recent DOE hearing on the issue, seems to be having some impact. The CEO of Shell, Peter Voser, said, “Exports will happen. But I hope that the US will actually keep most of the gas back because it will help them to industrialize parts of the US more.” Shell is actively planning a large chemical complex in Marcellus shale territory, and has also announced an LNG investment—not for export at this point, but to create a gasoline substitute. (NG transport fuel is practical for fleets with predictable routes and centralized refueling.) Dow has just withdrawn from a partnership in a proposed $6.5 billion LNG terminal. If powerful manufacturing interests continue to join the AEA, broad-based industry groups, like the Chamber and the NAM may well want to modify their unequivocal support for exporting. The AEA also seems to have found the ear of Senator Ron Wyden (a Democrat from Oregon), the incoming chairman of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, who is holding hearings before taking more definitive steps toward wider exporting. During all this, however, the DOE approved a second Louisiana LNG terminal, for shipping to countries who are covered by FTAs, which legally the Department has no right to turn down. (The company has also filed an application for non-FTA nations.) This second plant is about half the size of the Cheniere facility, and would not be opened until 2018. Recently a senior DOE official told a meeting of state regulators that they intended to “move carefully” on approving such permits.19

There is ample justification to put all permitting on hold. The NERA report is hopelessly flawed. It should either be withdrawn or, as Dow suggests, referred to peer review. The United States doesn’t have to leap to solve the world’s energy problems. Let’s look after the home front first, see how well production rebounds as new pipelines open markets and prices rise. If supplies turn out to be as good as the bullish projections, we can gradually let exports run free without damaging the markets at home. In the meantime, Senator Wyden has adroitly suggested approving LNG exporting but only to a level that comports with the forecasts of the NERA report. The “public interest” justification for the limitation would be to avoid wasting tens of billions in building another round of white elephant LNG facilities like the unused de-gasification plants.

But for all the potential economic benefits of the shale revolution, they won’t be realized without coming to grips with the industry’s dark side.

_____________

* Flaring is more environmentally friendly than simply dumping the gas into the atmosphere, since it converts methane into CO2, which has less of a greenhouse effect than methane, at least in the short term. Concentrated quantities of methane are also explosive.

* A barrel of oil, remember, has about six times the energy content of the thousand cubic feet of gas which is the pricing unit at the Henry Hub. The 7:1 rule of thumb takes into account that ethane is somewhat harder to transport and to convert into ethylene than naphtha.

* There are worries about the availability of qualified American workers, but they may be overdrawn. The energy industry has no obvious recruitment issues. If you pay them, it seems, they will come.