The Limits of U.S. Territorial Expansion

Robbery by European nations of each other’s territories has never been a sin, is not a sin today.

To the several cabinets the several political establishments of the world are clotheslines; and a large part of the official duty of these cabinets is to keep an eye on each other’s wash and grab what they can of it as opportunity offers.

All the territorial possessions of all the political establishments in the earth—including America, of course—consist of pilferings from other people’s wash.

Mark Twain, 1897

Why did the United States stop annexing territory? Mark Twain’s country was ten times larger than the colonies that declared independence in 1776, the result of expansionism by Thomas Jefferson, James Polk, William Henry Seward, and countless other U.S. leaders.1 Yet since Twain’s death in 1910 the United States has made no major annexations. Political scientists and historians alike have highlighted the U.S. shift from territorial expansion to commercial expansion, arguing that transformations in the sources of economic wealth and military power undercut the profitability of further annexations after the mid-nineteenth century. However, this conventional wisdom overstates the importance of material constraints on U.S. expansionism and neglects the main reason U.S. leaders rejected the annexation of their remaining neighbors: its domestic political and normative consequences.

By absorbing external territory into the state, annexation necessarily changes the state. Some of those changes are positive—for example, increasing its future wealth and security by gaining natural resources and population or controlling strategic terrain. These potential benefits may stoke leaders’ expansionist ambitions. Yet annexation may also change the state in ways that leaders consider negative—for example, distorting its institutions and demographics in ways that undercut their domestic political influence or their normative goals for the state. Even opportunities to pursue annexation that appear profitable in material terms may be undesirable for leaders who fear these domestic costs.

Two factors made the presidents, secretaries, and congressmen who shaped U.S. foreign policy during the nineteenth century especially sensitive to annexation’s domestic costs: democracy and xenophobia. First, they were acutely aware that their democratic institutions left them vulnerable to domestic political shifts resulting from the assimilation of new populations or the admission of new states. At the same time, they valued those democratic institutions enough to grant all major territorial acquisitions an eventual path to statehood, rejecting endless imperialism and militarized rule as threats to democracy at home (at least until 1898). Second, their xenophobia fueled widespread opinions of neighboring peoples as undesirable candidates for U.S. citizenship. As a result, virtually all viewed large foreign populations as deterrents, sources of moral and cultural corruption that would degrade the United States and undermine the popular sovereignty of their existing constituents if annexed.

Together, democracy and xenophobia raised the potential for annexation to impose formidable domestic costs from the moment the Constitution was ratified. This notion—that the factors most profoundly limiting U.S. territorial expansion were in place from the earliest days of the Union—is a provocative one. After all, scholars usually search for the cause of some effect by asking what else changed when that effect appeared. Most previous studies have followed this approach, explaining the end of U.S. annexation by asking what else changed by the late nineteenth century and identifying economic changes like industrialization and globalization or military transformations like nationalism and regional hegemony as the most likely culprits.

Yet in this case it turns out that the answer was present all along: the U.S. pursuit of annexation came to an end not because of any new development but because an old process had run its course. U.S. leaders did not fundamentally change their expansionist calculus in the mid-nineteenth century; rather, they confronted the prospect of annexing neighboring territories episodically as opportunities arose, deciding whether or not to pursue each specific territory based on its material, political, and normative merits. Once they had rejected a neighboring territory, their successors rarely reversed that decision, and one by one each remaining neighbor was either annexed or understood to be better left independent.

In this way U.S. leaders pursued annexation throughout the nineteenth century by picking and choosing from among their potential options until they ran out of desirable targets. Congressional majorities supported presidential efforts to annex areas like Louisiana and California, but they delayed similar efforts in Florida and Texas and defeated efforts to gain more of Mexico and Cuba. Time and again they raised objections to the domestic costs of annexation, and as they crossed their remaining neighbors off their list of viable targets, the practice gradually disappeared from U.S. foreign policy. To recognize that annexation has domestic consequences and that those consequences bear on leaders’ decision making is to recognize that in international politics, as in the human diet, you are what you eat. And the United States has always been a picky eater.

What Is Annexation?

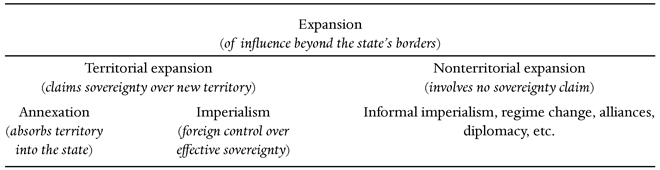

Like many terms, “annexation” has often been used in vague and contradictory ways. In this book, consistent with its dictionary definition, annexation refers to the absorption of territory into a state. The most straightforward way to think about annexation is as a subset of territorial expansion, which is itself a subset of the expansion of international influence (table 1.1). Expansionism, or states’ pursuit of influence abroad, has attracted consistent interest from international security scholars due to its role in causing wars and shaping the international system.2 While most forms of expansionism simply aim to increase one state’s leverage over another’s policies, territorial expansion sees a state claim Westphalian sovereignty over an area beyond its previous borders, declaring itself to be the highest political authority there and proscribing foreign interventions.3 Territorial expansion may increase the state’s economic and military power more efficiently than other forms of expansionism—depending on its administrative and technological abilities to utilize its new territory—which explains why it is simultaneously a coveted foreign policy goal and a potent source of international conflict.4

Territorial expansion, in turn, comes in two forms, annexation and imperialism, distinguished by whether the state fully absorbs its new territory or rules it separately and subordinately. A state in international relations, as opposed to U.S. states, is an institutional order that exercises paramount political authority and a monopoly on legitimate violence within its borders.5 Annexation expands that order by integrating new territory within its core protective, extractive, and legislative institutions. This doesn’t mean that states are internally homogeneous—no state entirely is—but rather that a state’s relationship with the annexed territory comes to mirror its relationship with its other constituent territories. By merging the new territory into the state itself, annexation enables leaders to redefine their national homeland, molding local identities, institutions, and cultural politics to reduce the likelihood of future unrest and maximize deterrent credibility in the eyes of international rivals who might desire to gain that territory for themselves.6

Table 1.1 Forms of international expansion

In contrast, imperialism establishes “foreign control over effective sovereignty,” in Michael Doyle’s phrasing.7 It too involves a new sovereignty claim, but the state rules its empire externally through institutions separate from and subordinate to those governing itself. Imperialism thus represents a state’s deepest method of expanding its influence abroad without expanding the institutional order that defines the state itself. Like nonterritorial forms of expansionism, imperialism may function as a precursor to annexation. For example, the United States pursued diplomacy, economic and cultural penetration, regime change, and imperialism in Hawaii before annexing it. But leaders may also pursue imperialism without any intention to annex territory. Those primarily concerned with extracting resources from a territory may prefer imposing institutions designed to streamline that process via imperialism rather than extending their state’s more cumbersome legal institutions via annexation. Similarly, leaders whose authority depends on ethnic nationalism may prefer to subordinate areas inhabited by other ethnicities via imperialism rather than compromise the perceived purity of their nation by annexing them.

Distinguishing between annexation and imperialism is crucial to understanding why the United States lost its early appetite for territorial expansion. U.S. leaders tended to think of territorial expansion and annexation as one and the same, imperialism being valid only on a transitional basis to prepare territories for integration into the Union. Leading a country born through anti-imperial revolution and infused with liberal ideology, they widely assumed that any territories they acquired would eventually gain representation either by enlarging existing states within the Union or, as quickly became the norm, by admitting new states to the Union. Most leaders rejected the notion of perpetual imperialism as fundamentally incompatible with American democracy. It emerged as a serious proposition during their debates only when there was widespread agreement that potential statehood was unthinkable, notably with regard to southern Mexico in 1848 and the Philippines in 1898. In other words, when U.S. policymakers considered opportunities for territorial expansion, they considered them first and foremost as opportunities for annexation.

This book seeks to explain why U.S. leaders pursued annexation when and where they did, not why their efforts succeeded or failed. Since annexation extends a state’s institutional order over new territory, it cannot occur without conscious implementation by state leaders. There are no accidental annexations. Unlike a balance of power, which may persist for centuries despite great powers’ frequent attempts to overturn it and dominate each other, the pursuit of annexation is necessary for its occurrence.8 Explaining why the United States stopped pursuing annexation can therefore tell us why it stopped annexing territory.

U.S. foreign policy today continues to feature other forms of expansionism, including diplomacy, foreign aid, sanctions, military occupation, regime change, and (in a mostly informal way) imperialism. Its military reaches all corners of the globe, yet the U.S. domestic political system remains limited to part of North America, seemingly invalidating Joseph Stalin’s mantra that “everyone imposes his own system as far as his army can reach.”9 For all their rhetoric about creating an “empire of liberty” and fulfilling their “manifest destiny,” U.S. leaders annexed far less territory than was feared by neighbors who quaked before the “northern colossus” and European leaders who assumed that further U.S. territorial expansion was “written in the Book of Fate.”10 Why did U.S. leaders stop pursuing annexation?

Why Abandoning Annexation Matters

The reasons why the United States stopped pursuing annexation should interest scholars and students of international relations, diplomatic history, American history, and American politics as well as members of the broader international public. By choosing to pursue only the territories they did, U.S. leaders contradicted typical patterns of great power behavior throughout history, offering intriguing puzzles to theories of international politics. Moreover, their decisions fundamentally shaped the geopolitical, economic, demographic, institutional, and ideological development of the United States across the centuries that followed, with repercussions that continue to echo through its current flaws and virtues. Finally, their rejection of further annexations enabled the creation of the modern international order, and understanding why they did so can help us understand why that order looks the way it does and how long we should expect it to last.

U.S. territorial pursuits differed from typical great power behavior in two major ways: (1) by targeting land rather than people, and (2) by declining as U.S. power grew. Most great powers in history have spent their blood and treasure trying to absorb nearby population centers and their workforces, which could be taxed and conscripted, rather than uninhabited lands requiring extensive settlement in order to yield a profit.11 They did so with good reason, since population and wealth are the building blocks of military might. Yet U.S. leaders preferred to annex sparsely populated lands like Louisiana and California, expelling many of the inhabitants they found there. Moreover, they intentionally declined opportunities to absorb population centers in eastern Canada, southern Mexico, and the Caribbean despite the impressive material benefits those territories offered. In short, when the United States pursued annexation, its choice of targets reversed the usual great power appetite.

U.S. leaders also broke from historical precedent by abandoning territorial ambitions as their power grew. International politics used to be defined by a quest for conquest: from Alexander and Qin Shi Huang to Genghis Khan and Napoleon, the list of historical conquerors “could go on almost ad infinitum.”12 Those leaders saw increases in their own power as opportunities to conquer and absorb their neighbors, making history trend “toward greater accumulation and concentration.”13 The United States helped reverse that trend, rejecting further annexations even as it rose toward an unprecedented position of global unipolarity. Robert Gilpin’s maxim that “as the power of a state increases, it seeks to extend its territorial control” may hold true for the United States if broadly conceived to include spheres of influence and alliances, but it is squarely defied by the pattern of U.S. annexation.14 In short, the United States converted its wealth into power but stopped translating that power into further territory.15

U.S. leaders’ decisions to depart from great power precedent in these ways had profound consequences for the development of both the United States and the international system. The course of race relations in the United States is inseparable from early U.S. leaders’ decisions to pursue land rather than people, which ensured that they could engineer the demographic future of territories they annexed.16 Successive generations of U.S. leaders manipulated federal land policies to recreate racial hierarchies on the frontier, promoting the Anglo-American domination of local politics before each new state was admitted to the Union.17 Denying representation to Native Americans and refusing to annex populous territories like Quebec and Cuba reinforced those hierarchies within the federal government by preventing its early racial, religious, linguistic, and cultural diversification. Those racial hierarchies, in turn, informed the development of virtually all aspects of U.S. society, from civil rights and labor relations to partisanship and liberal ideology, to say nothing of the controversy over the spread of slavery into annexed territories, which ignited sectionalism and the Civil War.18

In addition to its demography, U.S. leaders intentionally molded the geopolitical, economic, institutional, and ideological development of their country to match their normative visions. Controlling New Orleans and Florida secured the seaborne trade of the Mississippi River valley, fueling early settlement and economic development, while conquering California ensured U.S. regional hegemony and facilitated trade with Asia. Decisions to pursue or reject annexation shaped the development of executive power (e.g., Jefferson’s annexation of Louisiana despite questionable constitutional authority), legislative power (e.g., Congress’s annexation of Texas by joint resolution), and judicial power (e.g., the Insular Cases), as well as the relationships among the three branches.19 U.S. leaders’ deliberate refusal to conquer neighboring societies despite their growing wealth and power also fed their self-images as an exceptional nation acting on a higher moral plane than the old empires of Europe.20

Beyond their domestic significance, these decisions had global consequences. By removing annexation from the U.S. foreign policy agenda, nineteenth-century U.S. policymakers laid the groundwork for their twentieth-century successors to condemn the practice of conquest internationally. From positions of power after both world wars, U.S. leaders advocated a new international order prohibiting forcible annexation. The United Nations Charter reads, “All members shall refrain . . . from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.”21 This principle came not from nature, heaven, nor international consensus—it came from the United States. Declaring that “no right exists anywhere to hand peoples about from sovereignty to sovereignty as if they were property,” President Woodrow Wilson insisted over British objections that the League of Nations Covenant feature a territorial guarantee.22 Three decades later President Franklin Roosevelt’s advisers composed the UN Charter and painstakingly choreographed the San Francisco conference where it was signed.23 Subsequent presidents gave teeth to the norm against conquest by punishing violators, from the Korean War, when Harry Truman saw “the principles of the United Nations . . . at stake,” to the Gulf War, when George H. W. Bush reaffirmed that “the acquisition of territory by force is unacceptable.”24

The prohibition of conquest drives many other characteristics of the modern world, from how many countries are on the map to how we think about national security and what day-to-day diplomacy looks like. Europe consolidated “from some five hundred more or less independent political units in 1500 to twenty-odd states in 1900,” but after World War II that trend reversed, and the number of countries ballooned.25 In contrast to previous eras, scholars have meaningfully spoken of “trading states” whose diplomacy focuses mostly on peaceful economic coordination rather than hostile security competition.26 Weak states with valuable resources like oil have been able to translate those resources into wealth and influence instead of being conquered by stronger neighbors, and many countries enjoy sovereignty today despite lacking the institutional and military strength that was once its prerequisite.27

Most important of all, the decline of U.S. annexation and the subsequent construction of this international order laid a stronger foundation for international peace than the world had ever seen. Alexander Hamilton observed in Federalist, no. 7 that “territorial disputes have at all times been found one of the most fertile sources of hostility among nations,” and numerous studies have confirmed his assessment.28 As other countries joined the United States in renouncing territorial ambitions, those disputes disappeared from entire regions of the world, diminishing the fear of foreign invasion among their inhabitants to an all-time low and allowing leaders to reorient military spending toward counterterrorism and distant interests rather than border defense.29

None of these developments was inevitable. The international order as we know it would not exist if twentieth-century U.S. leaders had used their immense resources to pursue conquest instead of outlawing it. Norms and institutions are not physical objects but social constructions, which means they thrive only if powerful advocates abide by them, rally support for them, and keep potential violators in line.30 It is hard to imagine U.S. leaders spear-heading a movement against forcible annexation had they not already ruled out further annexations of their own, a fact which should not be taken for granted given the land hunger of the early United States. As Nuno Monteiro has written, “When the world has a preponderant power, its grand strategy is the most important variable.”31 The world would be a very different place today if annexation remained on the U.S. foreign policy agenda, so the decline of U.S. territorial ambitions should feature prominently in any account of the origins of the modern international system.

Things that are rare are often forgotten. As the great power politics of the Cold War gave way to preoccupations with ethnic conflict and terrorism in the 1990s and 2000s, many people forgot about annexation, which for all its historical importance seemed of little relevance in the modern world. Then, in the spring of 2014, Russia annexed Crimea, shocking those who had assumed such behavior was a thing of the past. Secretary of State John Kerry exclaimed, “You just don’t in the 21st century behave in 19th century fashion.”32 The United States and the European Union levied sanctions against Russia as punishment, confirming expectations that any international territorial aggression would “put pressure on the United States as the dominant state in the system to respond and enforce shared norms against conquest.”33 Such expectations feel natural to us now, but when viewed in historical context they beg the question: Why does the dominant state in the system punish conquerors rather than pursuing conquests of its own?

The Picky Eagle

My central argument is that the domestic consequences of annexation can strongly affect its desirability. U.S. leaders repeatedly rejected the annexation of otherwise attractive targets for fear of their domestic political and normative fallout, even where they saw substantial material benefits ripe for the taking. When debating whether or not to pursue a territory, they often worried about whether its future population would favor themselves or their domestic political rivals once granted representation in federal elections. When they saw that population as fundamentally alien and too dense to be realistically Americanized, they rejected annexation rather than sharing their self-government with people they considered unfit for it. U.S. presidents, secretaries, and congressmen consistently targeted land rather than people because they feared the domestic impact of absorbing large alien populations into their democratic institutions, and they gradually abandoned annexation as they ruled out the desirability of their remaining neighbors. In other words, U.S. territorial ambitions were selective from the start.

Surrounded by weaker Native American tribes and outposts of distant European empires, early U.S. leaders enjoyed remarkable freedom of choice regarding where to expand and when (if ever) to stop. Although they were freer from external constraints than most great powers in history, their authority was based on democratic institutions which guaranteed that adding new states to the Union would alter the balance of power within the federal government, especially if those new states brought sizable populations with them. Accordingly, policymakers quickly began judging territorial opportunities on the basis of their domestic political consequences, and the hardening sectional divide gave rise to an explicit “balance rule” whereby each northern state added to the Union was counterbalanced by a corresponding southern state.

U.S. leaders interpreted the diverse racial, linguistic, cultural, and religious characteristics of nearby populations as evidence of their alien identities, distinguishing them from the Protestant, Anglo-American nation they envisioned and marking them as unfit to share in its self-government. As a result, abnormally for a great power and hypocritically for a nation of immigrants, the United States deliberately rejected the annexation of nearby population centers. Its leaders pursued Transappalachia, Louisiana, Florida, Texas, Oregon, and California specifically because they expected future Anglo-American settlement to overwhelm the relatively few Native Americans living in those territories. In contrast, U.S. leaders balked at opportunities to annex large alien societies in eastern Canada, southern Mexico, Cuba, and the Philippines that were ill-suited to comprehensive resettlement, afraid that assimilating their alien populations would corrupt the United States rather than improve it. Even the few who favored annexation in those cases did so not because they welcomed the inhabitants of those territories, but because they were more optimistic than their opponents about the prospect of Americanizing them.

Contrary to how the decline of U.S. annexation is often represented, nineteenth-century U.S. leaders did not suddenly and categorically abandon territorial expansion in favor of commercial expansion. Instead, they considered opportunities to annex neighboring territories on a case-by-case basis, seizing some and rejecting others, until eventually they had ruled out all of their remaining neighbors. Although their successors would champion an international order outlawing conquest, the history of U.S. territorial expansion is no tale of an altruistic Captain America fighting to make the world a better place. It is a selfish history. For all their talk of liberty and a civilizing mission, the thing most conspicuously absent from U.S. leaders’ annexation debates was any genuine interest in sharing self-government with the people they encountered. In the end, the strongest deterrents to U.S. territorial expansion were not formidable militaries but cities full of people that policymakers didn’t want in their country.

Nevertheless, U.S. leaders were neither greedy conquerors targeting everything in sight nor calculating materialists seizing every profitable opportunity. Explaining the decline of U.S. annexation requires appreciating that they were driven by a mix of power, institutions, and ideas: excitement about geopolitical opportunities, desires to increase their wealth and power, concerns about the domestic political balance and their own enduring influence over federal policy, visions of the grand republic they sought to build, and colored perceptions of other peoples’ identities relative to their own. The history of U.S. territorial expansion is one of leaders expanding where they could while still governing themselves the way they wanted, its limits set largely by their own limited visions for their country’s future and their fear of losing control of that future. The eventual result was something truly exceptional in world history: a preeminent global power disinterested in annexing its neighbors. Yet sometimes exceptional results emerge from the basest of causes.

Theories of International Expansionism

Political scientists have largely refrained from studying the pursuit of annexation, preferring to focus on the broader concept of expansionism and implicitly assuming no meaningful causal differences among its various forms. Existing theories have tended to focus on three factors that may limit states’ territorial ambitions: capability, security, and profitability. Some theories assume that leaders always desire more territory, expecting them to pursue annexation whenever their capabilities allow and to stop only when forced by internal or external constraints. Others assume that leaders’ primary objective is national security, expecting them to pursue annexation only insofar as it advances that goal. The most common view assumes that leaders judge annexation’s desirability on the basis of its material profitability, pursuing it whenever the benefits outweigh the costs. Yet despite much productive scholarship on great power politics and increasing interest in the U.S. rise to power, none of these theories offers a compelling explanation for the pattern of U.S. annexation.

Annexing territory is often the most efficient way for states to increase their relative power. This incentive leads some scholars to argue that international leaders should constantly harbor territorial ambitions, pursuing annexation except when prevented from doing so by internal or external constraints. Externally, powerful rivals may constrain leaders by threatening a costly war if they try to seize new territory.34 Internally, administrative costs resulting from overexpansion may drain too many resources for the state to afford further pursuits.35 Institutional checks and balances may also deny leaders the capacity to undertake ambitious foreign policy ventures by decentralizing control of foreign policy.36

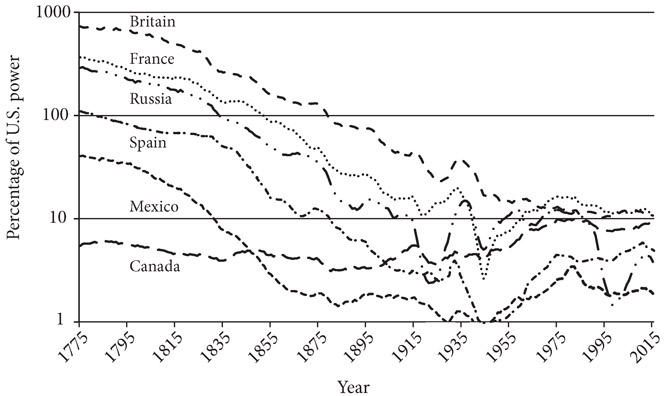

Capability-based arguments are often persuasive where severe constraints exist. After all, no leader can pursue annexation without having the capacity to do so. Compared to their international peers, though, U.S. leaders have been remarkably unconstrained. The United States has almost always been much stronger than its neighbors, becoming comparable to the European great powers by the mid-nineteenth century and surpassing them in the twentieth (fig. 1.1). That U.S. leaders rejected further annexations as their relative power grew to such heights makes little sense from the perspective of external constraints. Moreover, European great powers were reluctant to seriously contain U.S. expansion even in its early decades, preferring to conserve their resources for higher priorities in their own region.37 As British Prime Minister Palmerston wrote in November 1855, “Britain and France would not fight to prevent the United States from annexing Mexico, ‘and would scarcely be able to prevent it if they did go to war.’”38 Since other great powers consistently pursued territory in the face of far more formidable and committed adversaries, it is hard to believe that military deterrence significantly limited U.S. annexation.

FIGURE 1.1. Adversaries’ power as a percentage of U.S. power. Power proxied by net resources (GDP*GDP per capita), using estimated Maddison data from Christopher J. Fariss, Charles D. Crabtree, Therese Anders, Zachary M. Jones, Fridolin J. Linder, and Jonathan N. Markowitz, “Latent Estimation of GDP, GDP per capita, and Population from Historic and Contemporary Sources,” https://arxiv.org/pdf/1706.01099.pdf (accessed 11/2/2018); cf. Michael Beckley, “The Power of Nations: Measuring What Matters,” International Security 43, no. 2 (Fall 2018): 7–44.

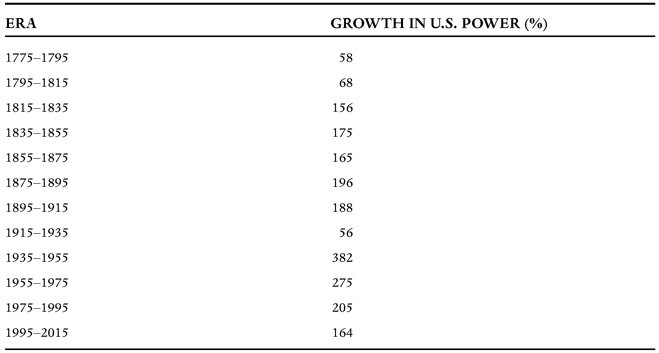

Overexpansion did not significantly constrain the United States either. The U.S. economy has never suffered a prolonged decline owing to the maintenance of too broad an empire. On the contrary, U.S. power has grown with remarkable consistency, both during and since its early territorial expansion (table 1.2). Like any other country, the United States has experienced periodic recessions that have temporarily limited the resources available for foreign policy, but such momentary hindrances offer little rationale for a lasting end to U.S. annexation.

Given their prominent role in U.S. domestic politics, institutional checks and balances are a more likely reason, and numerous studies have examined their impact on U.S. foreign policy. Scott Silverstone describes how the United States refrained from using military force or pursuing territory during numerous crises between 1807 and 1860 because its federal democratic institutions and the diversity of interests they represented made it hard to rally support for ambitious foreign policies, leading Congress to constrain presidential ambitions and presidents to exercise self-restraint.39 Fareed Zakaria recounts how U.S. leaders failed to translate growing national wealth into broader foreign policy goals between 1865 and 1889 because of “decentralized, diffuse, and divided” institutions, but shifting authority from the states to the federal government and from the legislative to the executive branch meant that between 1889 and 1908 “the executive branch was able to bypass Congress or coerce it into expanding American interests abroad.”40 Jeffrey Meiser describes U.S. foreign policy between 1898 and 1941 as marked by “delay, limitation, prevention, backlash, and retrenchment” due to restraints imposed by the “separation of powers, elections/public opinion, and federalism” as well as anti-imperialist norms.41 Jack Snyder argues that democratic “checks on concentrated interests that would promote overexpansion” and “public scrutiny of strategic justifications for global intervention” limited U.S. overstretch during the Cold War.42

Table 1.2 Growth in U.S. power, 1775–2015

Source: Power proxied by net resources (GDP * GDP per capita), using estimated Maddison data from Christopher J. Fariss, Charles D. Crabtree, Therese Anders, Zachary M. Jones, Fridolin J. Linder, and Jonathan N. Markowitz, “Latent Estimation of GDP, GDP per capita, and Population from Historic and Contemporary Sources,” https://arxiv.org/pdf/1706.01099.pdf (accessed 11/2/2018).

The breadth of historical research contained in these studies persuasively shows that institutional checks and balances have often affected U.S. foreign policy, but it is striking how poorly they explain the country’s behavior when the focus is narrowed from expansionism in general to annexation specifically. The federal executive was most constrained (by the state governments) in the early 1800s, precisely during the heyday of westward expansion, and the rise of the “imperial presidency” during the Cold War prompted no revival of U.S. territorial ambitions.43 If institutional constraints on executive power are primarily responsible for the decline of U.S. annexation, history books should be filled with tales of thwarted presidential plans to annex Canada and Mexico. Yet the record of presidential ambitions on the continent is largely consistent with the annexations that actually occurred. Moreover, institutional checks and balances cannot explain why majorities in Congress enthusiastically supported some potential annexations but rejected others.

Some political scientists have explained why leaders do not always want annexation by assuming that their primary goal is to ensure their state’s survival in the anarchic international system. As Sean Lynn-Jones writes, “States attempt to expand when expansion increases their security.”44 Leaders who prioritize national security should pursue annexations that mitigate strategic vulnerabilities while making sure their actions do not provoke costly retaliation or balancing coalitions.45 John Mearsheimer goes further, arguing that states best ensure their survival by maximizing their own relative power and hence that their leaders should be “bent on establishing regional hegemony.”46 In this view, the marginal security benefits of territorial expansion decline precipitously once regional hegemony is achieved, as leaders shift from conquering nearby rivals to deterring distant adversaries from projecting power against them. Although they disagree how much power makes a state most secure, these perspectives agree that U.S. policymakers lost interest in annexation once their conquest of California prevented Mexico from developing into a peer competitor, effectively guaranteeing long-term national security.

Regional hegemony has been a boon for the United States, yet U.S. leaders were neither consistently expansionist prior to 1848 nor content with refraining from expansion thereafter. Instead, they were reliably picky expansionists, primarily for domestic reasons. The War of 1812 is an especially problematic case for security-driven explanations: rather than work resolutely to eliminate their greatest security threat by driving British forces from Quebec, U.S. leaders proved disinterested in annexing the province despite the fact it represented both the greatest potential source of relative gains and the primary obstacle to U.S. domination of North America. Decades later, they similarly refused to annex southern Mexico and Cuba despite recognizing their geopolitical and economic value. Thus security-based arguments are built on the dubious notion that U.S. policymakers rejected the territories that would have contributed most to their presumed motivation. Moreover, even if regional hegemony diminishes annexation’s marginal security returns, a regional hegemon may still benefit from additional resources and geopolitical control. This explains why U.S. leaders continued to pursue Mexican border areas, the Pacific Northwest, and Hawaii after 1848, though not why they refused to annex Cuba (a future base for Soviet power projection against the United States) and opted for imperialism in Puerto Rico and the Philippines.

Why else might leaders lose interest in annexation? The best existing theories hold that modern economic and military transformations have made conquest less profitable.47 On the economic side, political scientists have identified several transformations that make it harder for conquerors to extract resources from a captured economy. Stephen Brooks describes how the global dispersal of production “means that conquering an advanced country may only result in possession of a portion of the value-added chain,” limiting the returns on its annexation.48 Modern economies are increasingly driven by human capital and information technologies, enabling workers to slash their conqueror’s profits by organizing dissent, scuttling their own economies, or fleeing.49 Conquest also brings greater economic oversight and less available risk capital, stifling innovation and hence productivity.50 Growing international trade and foreign direct investment have increased access to raw materials across borders, raising the opportunity costs of annexation by making more achievable without it.51 As Erik Gartzke writes, “If modern production processes de-emphasize land, minerals, and rooted labor in favor of intellectual and financial capital . . . then states can prefer to buy goods rather than steal them.”52

On the cost side of the ledger, military transformations have made conquest prohibitively expensive. Occupying forces struggle to pacify insurgencies that are not only inspired by nationalism to zealously resist foreign rule but also increasingly lethal due to the spread of small arms.53 The astronomical deadliness of major war has congealed into a deterrent through memories of past carnage and the potential for even limited aggression to escalate.54 Nuclear proliferation has purified that deterrence by raising the price of aggression against a nuclear-armed state to annihilation.55 The unprecedented military power of the United States presents potential aggressors with a more formidable adversary than ever before.56 Whether or not annexation’s economic benefits have decreased, these increased military costs may deter states from pursuing it.

Profitability arguments are not immune to criticism, however. Conquest may impair the productivity of a modern economy, but it is far bolder to claim that this has made conquest entirely undesirable given how much higher productivity is today than ever before.57 Peter Liberman observes that modern information technologies may facilitate repression as well as dissent, and “industrial societies are cumulative enough that conquerors can greatly increase their mobilizable economic base through expansion.”58 Moreover, globalization may actually proliferate opportunities for annexation by heightening great powers’ capabilities and destabilizing less-developed countries.59

Major war is a terrifying prospect (especially nuclear war), but that possibility may make small-scale conquests like Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea easier by deterring forcible retaliation.60 Even nationalist populations remain conquerable, as in western Europe during World War II, and nationalism can sometimes be manipulated to incite expansionism aimed at unifying a nation across borders or asserting the dominance of one nation over others.61 The most compelling modern deterrent is the prospect of fighting the formidable U.S. military, but that prospect cannot deter the United States itself from pursuing annexation; if anything, its leaders should be emboldened by their overwhelming might. When it comes to conquest, why don’t the watchmen seem to need watching?

Most important, nearly all of the phenomena highlighted by these profitability arguments emerged in the late twentieth century, and thus could not have caused the nineteenth-century decline of U.S. annexation. Nevertheless, the logic of profitability remains viable as a potential explanation thanks to its dependence on leaders’ perceptions and calculations. If nineteenth-century U.S. leaders primarily based their decisions on the material benefits and military costs of each opportunity, they may have rejected further annexations as unprofitable well before globalization or nuclear weapons entered the scene. This does not mean that every annexation must have generated a profit; leaders may misjudge opportunities due to misperceptions, biases, or incomplete information.62 Instead, profitability theory predicts that U.S. leaders facing an opportunity to pursue annexation should have based their decisions on its material profitability as they understood it at the time. This logic represents the current conventional wisdom among scholars of international relations. As Randall Schweller writes, “States expand when . . . it [is] profitable to do so.”63 As a result, profitability theory is the intellectual starting point of this book and the standard against which its contributions must be measured.

The History of U.S. Territorial Expansion

Historians have paid substantial attention to the roles of domestic factors like racism and sectionalism in limiting U.S. territorial expansion, though that attention remains largely confined to studies of specific periods like the Mexican–American War. Broader histories of U.S. expansionism, from the Wisconsin School of the 1960s–1970s to the more recent American Empire literature, have tended to downplay the decline of annexation, stressing instead the continuity of U.S. foreign policy across two centuries. As the newest generation of diplomatic historians focuses largely on twentieth-century phenomena like the Cold War, this tendency continues to overshadow the historiography of U.S. territorial expansion.

Although it has become a problematic generalization, the notion of U.S. foreign policy as continuously expansionist originated with a valuable insight, namely, that imperialism in the Philippines was not a “great aberration” from an otherwise innocent track record of U.S. foreign policy.64 William Appleman Williams’s revision of that prevailing view in the late 1950s inspired numerous students to understand the U.S. shift from territorial to commercial expansion as one of “form” rather than substance.65 Critics warned that this was oversimplifying. As Stuart Creighton Miller wrote, “Some scholars have not only refused to differentiate between continental and overseas expansion, but also make no distinction between formal empire and the more informal one involving indirect, largely economic, controls that the United States has long exercised in Latin America.”66 Nevertheless, the tendency to conflate diverse forms of expansionism proliferated after 9/11, with a wave of books labeling the Bush administration’s War on Terror as the latest symptom of an ever-expanding “American Empire.”67 The United States has never been truly isolationist, and demolishing that pernicious myth has been a valuable contribution, but by overselling continuity in the history of U.S. foreign policy, the American Empire literature has helped obscure meaningful variations within that history.68

When historians of U.S. expansionism have offered explanations for the shift from territorial to commercial expansion, they have tended to share political scientists’ emphasis on profitability logic.69 Williams himself argued that that shift was driven by profit: “The agricultural majority . . . was the dynamic element in the shift from continental to overseas empire. . . . The American farmer was a capitalist businessman whose welfare depended upon free access to a global marketplace, and who increasingly demanded that the government use its powers to ensure such freedom of opportunity.”70 Walter LaFeber similarly held that U.S. leaders pursued annexation until industrialization made them “almost entirely interested in markets (not in land).”71 Others such as Walter McDougall and Frank Ninkovich have more recently highlighted globalization’s role in reinforcing the turn to commercial expansion.72

In contrast, specialists in the era of Manifest Destiny recognized long ago that racism and sectionalism had limited U.S. leaders’ territorial appetites. As far back as 1963 Frederick Merk argued that westward expansion was not inevitable nor was public opinion united behind it, highlighting the “roadblocks of slavery and race” that prevented the annexation of all Mexico in the 1840s.73 Reginald Horsman reached a similar conclusion in his 1981 study of Anglo-Saxon racism, noting that the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo “obtained the largest possible area from Mexico with the least number of Mexicans. It was not the problem of the extension of slavery but the Hobson’s choice of racial amalgamation or imperial dominion that finally frustrated those who were prepared to take most or all of Mexico.”74 Four years later Thomas Hietala reiterated “the dilemma of desirable lands encumbered by undesirable peoples,” recounting, “When a more concentrated nonwhite population inhabited an area, as in Mexico below the Rio Grande or in Cuba, enthusiasm waned because of fears about amalgamation and racial conflict.”75

These insights have echoed across recent landmark histories emphasizing the role of identity in U.S. foreign policy.76 Eric Love rebukes prevailing narratives of a late-nineteenth-century “white man’s burden” in Race Over Empire, arguing that “political and legal questions of alien, nonwhite citizenship . . . unsettled imperialists and made many anti-imperialists.”77 David Hendrickson highlights the centrifugal forces unleashed by potential expansion into Canada, Texas, and Mexico while examining debates over U.S. identity in Union, Nation, or Empire.78 Analyzing federal land policies that encouraged Anglo-Saxon settlement, Paul Frymer observes in Building an American Empire that “fighting over the domestic institutional balance” and “white racism ultimately served to limit American expansion almost as frequently as it promoted it.”79 As implied by these studies of racism and sectionalism in U.S. history, but contrary to enduring myth, the United States did not transition cleanly from an early period of territorial expansion to a later focus on commercial expansion.80 The limits of U.S. territorial expansion fell into place episodically as leaders faced opportunities to annex neighboring territories and decided to seize some but reject others.

The Structure of the Book

This section offers a roadmap to the chapters that follow, including brief surveys of the historiographical state of the art for each of the five case study chapters, highlighting theory-relevant areas of established consensus that those chapters reaffirm as well as enduring debates or gaps where they make fresh historiographical contributions. Chapter 2 lays out my theory of annexation, suggesting that leaders often decide whether or not to pursue annexation on the basis of its domestic consequences as well as its material benefits and military costs. Although leaders usually like to increase their state’s relative power, doing so would be counterproductive if it undermines their control of state policy or their goals for the state itself. These domestic costs are particularly severe for democratic leaders annexing large alien societies, driving U.S. leaders to routinely view them as undesirable targets. The chapter concludes by deriving testable predictions and discussing the methodology used in the chapters that follow, which investigate why U.S. leaders chose to pursue the annexation of some territories but not others across twenty-three case studies between 1774 and 1898.

Chapter 3 examines the successful efforts to acquire European titles to Transappalachia, Louisiana, and Florida. As theoretical tests, these cases offer within-case evidence for the importance of domestic considerations in the sectional divisions over Louisiana and Florida, which promised domestic benefits to the Virginia Dynasty but costs to Northern Federalists, in contrast to the broadly popular pursuit of Transappalachia, which threatened minimal domestic costs under the loose institutional structure of the Articles of Confederation. These acquisitions are well documented, resulting in scholarly consensus on key findings like the risks U.S. negotiators took in demanding Transappalachia over their allies’ objections, President Thomas Jefferson’s economic and geopolitical motivations for pursuing New Orleans and Florida, and Northern Federalists’ opposition to those annexations.81 As a result, the greatest historiographical contributions of the chapter lie in emphasizing certain theory-relevant factors that often go underappreciated. For example, many histories of U.S. expansion begin in 1783 or later, overlooking expansionism during the Revolution.82 Even studies that address Transappalachia often undersell the contrasting domestic implications of its acquisition, which occurred prior to the Constitution’s ratification, and those of the other territories that followed.83 Treatments of the Louisiana Purchase and the Florida cession disagree as to whether presidents Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe deserve substantial credit for orchestrating those annexations or whether they were primarily driven by local or foreign actors.84 Although both acquisitions were notably facilitated by events beyond their control, I read all three presidents as uncompromising in their long-term southward ambitions and opportunistic in their expansionist policies.

Chapter 4 studies the U.S. pursuit of Native American lands between the administrations of George Washington and Andrew Jackson. As theoretical tests, these cases reveal how federal leaders’ domestic incentives shifted with the rise of frontier states, driving later administrations to abandon their predecessors’ plans for tribal assimilation and instead enforce removal. Historians have thoroughly examined federal civilization and removal policies, but the timing and causal responsibility for the change from one to the other remains subject to debate.85 Whereas many accounts emphasize removal as Jackson’s legacy, this chapter follows those that take a longer view of its emergence, locating removal’s origin as a concept with Jefferson, as common practice with Madison’s deference to frontier leaders, and as federal policy with Monroe.86 In contrast to accounts that describe removal as an inevitable consequence of U.S. military dominance over the tribes, this chapter sees U.S. power as an enabling factor rather than a deterministic one.87 It locates the driving cause of removal in the domestic costs of assimilation for frontier leaders, which lay dormant in the early federal government but boiled over once a critical mass of frontier states had been admitted to the Union.

Chapter 5 considers six major opportunities to annex territory in Canada: the revolutionary pursuit of Quebec, the War of 1812, the crises of 1837–42, the Oregon controversy, the Fenian raids, and the push for the Pacific Northwest. As theoretical tests, these cases cast doubt on profitability theory by revealing how U.S. leaders pursued sparsely populated western Canada while repeatedly declining to annex populous eastern Canada. Historians have not neglected the 1775 Quebec campaign, but this chapter pays particular attention to the endurance of U.S. northward ambitions throughout the Revolutionary War and the domestic political differences between this case and those that follow.88 The War of 1812 is frequently misrepresented as expansionist despite the opposite consensus among period specialists, and this chapter highlights its significance as the first time U.S. leaders consciously declined a profitable opportunity to pursue annexation.89 The chapter also offers a useful contrast between President James Polk’s Oregon diplomacy, which has received substantial attention, and U.S. reactions to the crises of 1837–42, which have gone relatively understudied as a negative case of U.S. territorial expansion.90 That said, its greatest historiographical contributions fall in the post–Civil War period, which, except for the purchase of Alaska, is often ignored. In contrast, this chapter scrutinizes U.S. responses to the Fenian raids and the Red River rebellion, and it contributes new archival research on Secretary of State William Henry Seward’s ambitions for British Columbia.91

Chapter 6 turns to six major opportunities to annex territory in Mexico: the Texas Revolution, the annexation of Texas, the Mexican–American War, the all-Mexico debate, the antebellum period, and the Maximilian affair. As noted above, specialists in these cases have led the way in revealing how domestic considerations limited U.S. territorial pursuits. Northern opposition to the spread of slavery delayed and nearly prevented the U.S. annexation of Texas, circumscribed U.S. ambitions during the Mexican–American War, and curtailed southern expansionism in the 1850s.92 Xenophobia took center stage in deterring the annexation of densely populated southern Mexico, solidifying U.S. perceptions of Mexico as a distinct nation that should remain independent.93 This chapter gives greater consideration to the expansionist ambitions of independent Texas than most studies, but the wealth of previous research on these cases means that its greatest historiographical contributions fall in the Civil War period, where my archival research uncovered more overt opportunities for expansion into Mexico than are typically recognized.

Chapter 7 investigates the potential annexations of Cuba before the Civil War, the Dominican Republic afterward, and Cuba, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam in 1898. The first case study builds on Robert May’s impressive research on southern expansionism, reinforcing his initial observations of sectionalism and racism as obstacles to the annexation of Cuba in the 1850s.94 Whereas many studies emphasize institutional checks and balances in recounting how Congress prevented President Ulysses Grant from annexing the Dominican Republic, my second case study builds on Eric Love’s work to highlight the xenophobia that fueled congressional opposition.95 Period specialists agree that it was neither yellow journalism nor the explosion of the U.S.S. Maine that drove U.S. leaders to declare war on Spain in 1898, as is often caricatured, but scholars continue to debate whether the resulting expansionism was more a product of the war itself or of the culmination of long-gestating pressures for penetration into Asia and the Caribbean.96 The chapter’s third case study challenges histories that emphasize continuity between earlier continental expansion and 1898 by questioning why Congress specifically refused to target Cuba for annexation, despite its being the primary cause and theater of the war as well as an attractive target for early U.S. leaders. Where many histories of Hawaiian annexation discuss racism as a justification, via social Darwinism or white man’s burden ideologies, the fourth case study goes further than most studies in examining how xenophobia fueled annexation’s opponents in Congress.97 Finally, the fifth case study builds on inquiries into the role of racism in U.S. policy toward the Philippines as well as the explosion of scholarship on Puerto Rico’s legal status, which has produced a strong consensus that U.S. leaders manufactured the category of unincorporated territories to retain sovereignty over islands inhabited by people they viewed as unfit for U.S. citizenship.98

Chapter 8 summarizes the book’s findings and explores its implications for U.S. foreign policy and international relations. The accumulated evidence strongly suggests that democracy and xenophobia worked together to undercut U.S. leaders’ interest in annexing their remaining neighbors, a conclusion which should inform our debates regarding American exceptionalism, benign hegemony, informal imperialism, and the apparent contradiction between U.S. liberal ideals and illiberal policies. These dynamics likely extend to other countries beyond the United States—a fruitful area for further research—with consequences for how we think about the sources of international territorial ambitions, the democratic peace, and the origins and sustainability of the norm against conquest. In the end, this book resolves a central puzzle of international relations: why did the United States stop annexing territory? And it does so in a way that contributes to our understanding of American history, undercuts enduring myths of U.S. altruism, and bridges a key logical gap in prominent histories of U.S. expansionism by explaining why U.S. foreign policy has continued to expand since 1898 but U.S. territory has not.