RIVKA FELDHAY

3 The use and abuse of mathematical entities: Galileo and the Jesuits revisited

INTRODUCTION

On the second day of the Two New Sciences1 the three interlocutors Sagredo, Simplicio, and Salviati suspend their learned conversation on forces of fracture and resistance to indulge in yet another digression among many that have become well known as characteristic marks of Galileo's texts. Sagredo, the aristocratic amateur of natural philosophy and mathematics addresses Simplicio, the Aristotelian philosopher, with the following remark:

What shall we say, Simplicio? Must we not confess that the power of geometry is the most potent instrument of all to sharpen the mind and dispose it to reason perfectly, and to speculate? Didn't Plato have good reason to want his pupils to be first well grounded in mathematics? (133)

Simplicio, portrayed in this not very polemical text as an open-minded scholar, graciously responds:

Truly I begin to understand that although logic is a very excellent instrument to govern our reasoning, it does not compare with the sharpness of geometry in awakening the mind to discovery.

This unexpected agreement encourages Sagredo to further elaborate his position by saying:

It seems to me that logic teaches how to know whether or not reasonings and demonstrations already discovered are conclusive, but I do not believe that it teaches how to find conclusive reasonings and demonstrations.

The edge of Galileo's ambitious project is enfolded in this brief exchange. Suggesting that geometry is a tool of discovery, whereas logic serves for assessing and criticizing arguments already known, Sagredo hints at the need to restructure the body of natural knowledge, substituting mathematics for logic as the organon of philosophy.

Ever since the nineteenth century, the historiography of science has fruitfully oscillated between different interpretations of what really constituted the core of Galileo's project. Experimental practices,2 mathematical Platonism,3 Aristotelian method,4 or some kind of a combination between experiment and mathematical deductivism5 are just a few among many alternative clues suggested by scholars along the years, by means of which the “essence” of Galileo's enterprise was thought to be captured. Whatever may be the angle through which Galileo's theory and practice are to be examined, it is beyond doubt, however, that the transition from traditional natural philosophy to the new science was much effected by the role assigned to mathematics in Galilean discourse, though not necessarily by its actual mathematical techniques.

Many questions have been asked about the new status of mathematics in Galileo's scientific program. Some historians were most interested in the origins of Galileo's mathematical orientation, which could be found in classical mathematical texts, or perhaps among the medieval calculators, or the Parisian School, or among the mathematical practitioners of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Italian courts.6 Other historians were more interested in the contents of the justifications, devised by Galileo for using mathematics in the investigation of nature, and in their philosophical validity.7 Yet others preferred to emphasize the compatibility or incompatibility of mathematical arguments with the established method of the official science of sixteenth-century universities.8

To this variety of points of view I would like to add yet another aspect. Assuming a breach within Galileo's scientific project (which has already been pointed out by other historians), but also taking into consideration the context of Galileo's project in the field of practicing mathematicians, Galileo's justification of the status of mathematics may be better understood if we realize and analyze the complexity of its various functions: on the one hand to create a bridge between the different and sometimes incompatible directions of his own inquiries, conferring upon them the coherence of a research program; on the other hand to construct for himself a differentiated position among other mathematicians working in the same cultural field.

My essay, then, is a preliminary attempt to provide a framework of some less discussed aspects of Galileo's politics of knowledge. The justification of the status of mathematics is not examined here as the source from which a coherent research project necessarily emerged but as a necessary strategy of creating coherence for a project whose inner connections were not yet clear. Furthermore, the cultural context within which such strategy was mainly practiced consisted in a newly reconstructed community of mathematicians whose field of research was in the process of being defined.

My point of departure is the debate over the mathematical sciences that broke out in Italy in the middle of the sixteenth century and has been known in historical literature as the controversy on the certainty of mathematics (De certitudine mathematicarum disciplinarum).9 The cultural significance of this debate emerged as it began to play a role in the actual practices of mathematicians attempting to gain for their project a central educational role. Jesuit mathematicians made the first institutionally organized effort to place the mathematical disciplines at the heart of a broad cultural program.10 Therefore, my focus in the first part of this essay is on the appropriation and development of the main themes of the debate as strategies of legitimizing their field of knowledge.

Galileo's science sprang from the same roots as the Jesuits’ program, and it shared much of its spirit with Jesuit mathematicians. The dynamics of Galileo's own development, however, pushed him into formulating a different agenda. At the same time, Galileo never detached himself completely from his roots, which assumed the form of a counter-discourse, insisting in his texts but split from his later agenda. The second part of this paper comprises an analysis of various passages from Galileo's Dialogue that exemplify the structural split within his own scientific program.

The third part follows the traces left in Galileo's Dialogue by the debate on the certainty of mathematics. Galileo's final annihilation of the discourse on mathematical entities – used by the Jesuits as their main legitimation – was a way of covering up the split in his own program, as well as strategy of differentiating his position from that of the Jesuit mathematicians.

1. THE CONSTRUCTION OF A FIELD FOR MATHEMATICIANS

In 1547 Alessandro Piccolomini, a member of the Accademia degli Infiammati, which was active in transmitting humanistic and Renaissance learning to the University of Padua, published a paraphrase of Aristotle's Mechanical Questions, appendiced by a commentary on the certitude of mathematics (Commenatrium de certitudine mathematicarum disciplinarum).11 Piccolomini's treatise challenged the accepted interpretation of Averroes and the Latin commentators, according to which in the hierarchy of the speculative sciences (scientiae) the mathematical disciplines were the first in the order of certainty, because their demonstrations were the model for demonstrations potissimae, perceived as the strongest and most certain of all other forms of demonstration.12 Following his reading of Proclus's Commentary on the First Book of Euclid's Elements, and of the Greek Commentators, whose recently translated work started to transform the reading of Aristotle in those same years,13 Piccolomini changed his adolescent opinion on that matter and claimed that geometrical demonstrations had nothing to do with scientific demonstrations potissimae.14

Piccolomini's treatise is a natural point of departure for understanding the appropriation and rejection of the ancient discourse on mathematical entities in the cultural context of early modern science. Its arguments, recently represented and analyzed in detail by Anna De Pace amount to a strategy that attempted to establish a clear boundary between mathematics and natural philosophy, while still legitimizing mathematics as an autonomous but inferior science.

The ontology of mathematical entities delineated by Piccolomini consisted in a combination of his Averroistic interpretation of “quantity” as the most general accident of primary matter, his Aristotelian theory of abstraction, and his Aristotelian reading of Proclus's thesis about the middle position (medietas) of mathematics. The quantity that inheres in primary matter before it is embodied in any substantial form was, in Piccolomini's words, “quantum phantasiatum,”15 the most common and basic of all sensible accidents16 and undetermined by any specified form. Piccolomini calls it “indeterminate quantity” and describes it thus:

… since matter is by its own nature devoid of any substantial form, and nevertheless has in it the possibility and readiness for all forms: thus the quantity which is proper for it is likewise bare and devoid of any determination or figure; and is nevertheless able and disposed to receive all terms or figure…17

Quantity is the most immediate and manifest property of matter and hence the easiest to abstract. Mathematical entities are easily liberated from matter by simple abstraction. The certainty with which they may be known is connected to their simple being. Devoid of complexity and depth, they are the most accessible for human cognition.18

Piccolomini, however, denied that the certainty achieved by mathematical demonstrations, whose subject matter is quantity, can be identified with scientific demonstrations. Using Proclus's analysis of Euclid I, 32 [In any triangle, if one of the sides be produced, the exterior angle is equal to the two interior and opposite angles, and the three interior angles are equal to two right angles] as an example for a noncausal demonstration he claimed it could not be identified with demonstration potissima, and he generalized this critique to all Euclidean proofs. Thus, his conclusion was that mathematical demonstrations were not really scientific in the Aristotelian sense.19

The separation of mathematical objects from substance, which explains, according to Piccolomini, their capacity to be known with a high degree of certainty, but which differentiates them from the objects of natural philosophy entangled in the reality of matter and form, also accounts for the difference between geometrical and philosophical demonstrations. Together these differences justify the distinction between mathematics as a science of abstract being – “quantum phantasiatum” – and natural philosophy, the science of reality. Even the mixed sciences, which apply mathematics to the investigation of nature, are devoid of real scientificity, and though they are extremely useful for humanity they still represent an inferior form of knowledge compared to natural philosophy. One example used by Piccolomini to substantiate this difference concerned the sphericity of the Earth and heaven. Whereas the natural philosopher attempts to discover the essential causes inherent in natural things, the astronomer considers their mathematical properties without asking about their true nature:20

…the astronomer…even while considering that the heaven is spherical, or that the earth round, does not need, for this [purpose] to know the true nature and their substance, but solely from the positions, figures and aspects seen in the heaven argues that they are of such form…for this [reason] it can be concluded, that though the science of natural things often overlaps with other sciences in treating a certain subject, or in demonstrating a certain conclusion, nevertheless the natural philosopher differs from all the others in that never separating the concepts of the forms from those of their proper matter, he treats both natures as related to each other, namely the matter and the form: which are the two principles, and the intrinsic causes of natural things.

In the flourishing community of Paduan mathematicians and Averroist philosophers which sustained a rich technical and scientific tradition at the time,21 including among its members people such as J. Contarini, D. Barbaro, G. Moleto, and N. Tartaglia, Piccolomini's treatise was received with much surprise and irritation. This was the natural audience for Francesco Barozzi, a young Venetian patrician. He had been lecturer of mathematics since 1559 and immersed in the study of Proclus's Commentary for some years, publishing (in 1560) his Opusculum – consisting in an oration and two questions on the certainty and the middle position of mathematics – in response to Piccolomini's startling innovation.22 The work was dedicated to D. Barbaro, seeking his protection for daring to challenge Piccolomini's recent publication. Barbaro responded with a letter – thus leaving some testimony for the hostility toward Piccolomini in his circle – in which he expressed his long-term expectation for a refutation of Piccolomini's opinion as “new and unfounded” (“nova et non fondata”).23 In 1559 (the first year of his lectureship) Barozzi read Proclus's Commentary in his course and left his interpretation in manuscript form.24 As a Venetian patron he corresponded extensively with prominent Italian mathematicians, among them Clavius, Guidobaldo del Monte, Giuseppe Moleto, and other eminent personalities.

Barozzi's work is of interest as a main source of interpretation and transmission of Proclus's Commentary, which he edited and published in the same year as he published his Opusculum.25 Accepting Piccolomini's thesis about the medietas of mathematics (between philosophy and the “divine science” metaphysics) as the basis for reconciling Aristotle and Plato, Barozzi neglected Piccolomini's interpretation of this middle position in terms of abstraction and attempted to ground the certainty and scientificity of mathematical demonstrations in Proclus's claim to the innateness and priority of mathematical entities.

Thus Barozzi was the first to legitimize a reading of Aristotle in terms of a Neo-Platonic ontology of the objects of mathematical discourse. Barozzi, following Proclus, claimed that Plato arranged the sciences according to the perfection of their entities. Therefore, according to him: “Divine philosophy holds the first place, mathematics the second, natural philosophy the third.”26 At first glance it seems that Aristotle refused this order, since he gave priority to natural philosophy. This opposition is superficial, however, according to Barozzi. In truth, Aristotle accepted the middle nature of mathematical entities, since they mediate between matter and the purely abstract entities of metaphysics. “And indeed, this middle essence cannot be anything else but mathematical.”27 But the middle position of mathematics means that the certainty of knowledge of its objects is superior to that of the knowledge of the objects of natural philosophy. And because there must always be a correspondence between the objects of a science and its demonstrations, it follows that mathematical demonstrations are more certain than any other kind of demonstration.28

Two historical facts may echo something about the diffusion and transmission of Barozzi's ideas. That Galileo owned the Opusculum is known from the description of his library by Antonio Favaro.29 Also, in the “Prolegomena” to his commentary on Euclid's Elements discussed below, Christopher Clavius admitted to the inspiration of Barozzi and his work on Proclus. Thus, Barozzi's reluctance to take issue with Piccolomini's Aristotelian theory of abstraction – in spite of his rejection of other parts of Piccolomini's reading – and his preference for blurring Proclus's harsh critique of this theory allowed mathematicians of different convictions to draw upon his ideas without giving full account of the profound differences between the Platonic and the Aristotelian position on the mathematical entities.

A more radical opposition to Piccolomini, entangled with a more radical reading of Aristotle in Proclean terms, characterizes the work of Pietro Catena, who held the chair of mathematics in Padua for almost thirty years (1547–1576) and developed his ideas in three works, all touching upon the relation between mathematics and philosophy, their objects, their demonstrations, and their status in the hierarchy of the speculative sciences.30

The main thesis common to Piccolomini and Barozzi, but rejected by Catena, was that of the middle position of mathematical entities, for which Catena substituted a view of mathematical universals as predicates of the rational soul that he derived from his Platonic reading of the Posterior Analytics. Unlike physical phenomena, which are perceived primarily through sense experience, mathematical entities are pure intelligibles, constituted only through a rational process of thought and in no need of the senses to be recognized.31 Catena believed in their innateness and invoked the theory of reminiscence to justify the pure intellectual nature of their recognition.32 But more generally, Catena subscribed to the view that all knowledge was first anchored in universals preexisting in the intellect, rather than in abstraction from particulars. Above all, the objects of geometricians – lines, points, and planes – originate in the soul, not in sense images.33

The clue to Catena's position may be his presupposition that any particular participates in a universal mathematical nature, although particulars cannot be reduced to such entities, because they also contain other elements in which they are distinguished as particulars. Science, according to Catena consisted essentially in the application of universal intelligibles to particulars, thus transforming recognition into actual knowledge.

To illustrate this process Catena used Aristotle's example of a bronze triangle recognized as participating in a universal (in this case a mathematical triangle) through an examination of the equality of the sum of its angles to two straight ones. The mind presupposes a bronze triangle and gradually excludes some of its properties (its bronzeness, for example) until it realizes that with the elimination of the three sides the property of the sum of the angles disappears.34 Aristotle and Euclid agreed on this idea of science, but they used different logical procedures – syllogism and mathematical demonstration respectively – as their practice. Therefore, Aristotle, in his Posterior Analytics, referred to two kinds of inductions,35 although he did not clarify the differences between them. Catena took upon himself to do just that, and this was probably the most original part of his contribution. Definition played an essential role in a syllogistic procedure, but a mere classificatory role in a geometrical one. To show this Catena picked up again Proclus's and Piccolomini's example of Euclid 1, 32,36 only to claim the opposite of their conclusion, namely that in spite of its difference from a demonstration potissima, it still led to true, certain, and actual knowledge of the particular.37 Thus, Catena agreed with Piccolomini about the difference between mathematical and syllogistic demonstrations, but insinuated – without actually articulating this conclusion clearly – that only mathematical demonstrations could serve in the discovery of new truths, whereas syllogisms were effective in the orderly presentation of old ones.

Catena's interpretation of the concept of universal science, which he deemed common to Aristotle and Euclid, enabled him to include the mixed mathematical disciplines within this framework, without any need to distinguish their status from the rest of the sciences. The basic difference was that in the constitution of corporeal entities (such as rays of light, for example, compared to geometrical lines) as objects of science not only pure rational thought but also experience played a major role. Still, the principles of the science as well as its basic concepts were universal intelligibles and the causes discovered were the product of rational discourse, not of the senses.38

The positions of Piccolomini, Barozzi, and Catena – who were the first to construct some archetypal strategies in early modern politics of knowledge – may be summed up as follows: Piccolomini recognized the superior certainty of mathematics but was most interested in bounding it within a separate, autonomous domain. The high degree of certainty attributed to mathematics was related by Piccolomini to the inferiority of its objects, which were, in his perception, the most simplistic in the ontological sense and therefore the easiest to acquire knowledge about. In this sense they were radically differentiated from the objects of natural philosophy, representing a higher degree of complexity and allowing for intrinsic knowledge of their essence through a much more complex rational process culminating in the demonstration potissima. The boundary between mathematics and philosophy was clearly at the center of Piccolomini's interest. Barozzi, using a Proclean reading of mathematical entities, focused his interest on proving the scientificity – and not just certainty – of mathematics by stressing its middle position (medietas) between philosophy and metaphysics, both in the order of nature (ontology) and in the order of knowing (epistemology). This doctrine he deemed common to Aristotle and Plato and was the source of recognizing mathematical demonstrations as equivalent to demonstrations potissimae. The compatibility between the objects of a science and the kind of demonstrations it used led, according to Barozzi, to the inescapable recognition of the higher status of mathematics relative to philosophy. However, the question of the use of mathematics in natural philosophy was not really predominant in his writing. In fact, De Pace's interpretation emphasizes that it played a minor role in his mind.39 But this was the main focus of Catena's arguments. Attributing a common ideal of science to Aristotle and Euclid – in spite of a deep divergence of methods – Catena thought that mathematical demonstrations were superior to demonstrations potissimae as instruments of acquiring new knowledge. Hence, he claimed that knowledge of the world was only possible through the use of mathematical methods.

All three writers presupposed some kind of agreement between Aristotle, Plato, and sometimes Proclus on the certainty of mathematics, in spite of their different and sometimes oppository readings of their sources: Piccolomini stressed the agreement of Aristotle and Proclus on the middle position of mathematics – wrongly attributing to Aristotle a theory of abstraction – and used Proclus's occasional critique of some Euclidean proofs to claim the incompatibility of mathematical demonstration and demonstration potissima. Barozzi attempted to reconcile the Aristotelian and Platonic position on the medietas of mathematics but ignored the Aristotelian theory of abstraction. Catena attempted a Platonic reading of the Posterior Analytics in order to prove an idea of science common to Aristotle and Plato. It is thus clear that all three writers attributed a major role to the ancient authorities in their attempts to gain legitimation for their respective positions.

The debate over the status of mathematics in the sixteenth century signaled the beginning of a structural shift on the medieval map of knowledge toward a different understanding of the place of mathematics. The change was initiated by a variety of separate developments such as the activities of mathematical practitioners in Italian courts, the renaissance of Greek mathematical texts, the spread of Archimedean discourse, the emergence of Copernican astronomy, and the rise of the new algebra. But it was among the Jesuits that the first efforts were made to assimilate all these changes into an institutionalized research program with a special cultural and educational vocation. It is also in the context of the Jesuit program that the debate over the certainty of mathematics was appropriated and developed as a source for a variety of practices in the politics of knowledge.

The history of the efforts of Jesuit mathematicians to create for themselves a separate identity within a humanistic-scholastic educational project and to secure their status vis-à-vis the theologians and philosophers of the society has not yet been written. Recent historical scholarship, however, points to tensions between philosophers and mathematicians – concerning the scope and place of mathematics in the Jesuit curriculum, the interpretation of cosmological phenomena such as the nova of 1604, the motion of the Earth, the critique of Archimedes, etc.40 – all of which touched upon the problematic boundary between mathematical and philosophical discourse. In some of my previous work I have argued that the Jesuit policy of constructing boundaries between fields of knowledge functioned as a cultural mechanism of control enabling the reproduction of a Thomistic framework, in spite of the transgression of its boundaries which became common practice among Jesuit mathematicians.41 The traditional mathematical disciplines were the science of numbers, the science of continuous magnitudes, and pure and mixed mathematics. Two examples may illustrate the kind of dynamics created by the Jesuit appropriation of new areas of mathematical research that tended to undermine these traditional boundaries within the mathematical disciplines (or between mathematics and natural philosophy) and the practice of keeping the boundaries, which was also exercised by Jesuit mathematicians.

The Jesuits’ involvement is particularly interesting in two areas. The first concerns their role in the reception, assimilation, and transition of Vietà’s algebra. Whereas Clavius himself praised algebra, publishing his textbook on the subject in 1608, his work did not really assimilate the “new art” and the innovations of recent Italian algebraists.42 His student Staserio, however, who dedicated much of his life to building up the mathematical program of studies in the Jesuit college in Naples, succeeded in integrating the new algebra into the Jesuit curriculum.43 Baldini's historical researches have taught us that around 1600 the Collegio Romano became a center of debate over the innovations springing from the use of algebra in solving geometrical problems.44 The intense preoccupation with algebra could not take place, however, without challenging the boundary between discrete numbers and continuous magnitudes, as has been shown by Jacob Klein, and more recently by Lachterman.45 Nevertheless, the famous controversy between Paulus Guldin and Cavallieri over the method of indivisibles46 echoes the tendency of many Jesuit mathematicians to defend the traditional disciplinary divisions, in spite of their interest and even promotion of research topics that clearly endangered them.

No less significant was the involvement of Jesuit mathematicians in the Archimedean revival that took place exactly in the same years. The origins of this involvement go back both to Torres – the first professor of mathematics at the Collegio Romano – who was a student of Maurolico, and to Clavius who was in close contact with Maurolico and planned to publish his manuscripts.47 It is Baldini, again, who has pointed out the impact of these connections with Maurolico and through him also with Commandino's work, which was felt both through the emphasis on geometry and on Archimedean problems of measuring as well as through an interest in the Archimedean statical tradition of mechanics, thoroughly brought into contact with the medieval dynamical tradition in the context of the Jesuit “mixed mathematical science.”48 A most compelling piece of evidence for the new horizons opened up by the integration of the Archimedean tradition may be found in the plurality of works on centers of gravity, written by Jesuit mathematicians at the turn of the seventeenth century and later on.

It is well known that Clavius wrote on centers of gravity, but his work was not preserved. Staserio, Villalpando, Luca Valerio, and later on Guldin and Saint Vincent (all of them trained by Clavius in Rome) wrote on centers of gravity, testifying to the continuation of that tradition in Jesuit circles. Work on centers of gravity, however, was situated exactly on the borderline between mathematical and physical discourse. In fact, the concept of “weight” itself was conceptualized in qualitative terms in the context of Aristotelian physics and in terms of “quantity” in the Archimedean mathematical one. This exemplifies a clear point of interference and of potential tensions between mathematicians and philosophers.

The institutionalization and success of a mathematical program of studies and research was the context in which the debate on the certainty of mathematics was replicated, intensified, and developed in Jesuit circles. Benedictus Perera was the first to elaborate and deepen Alessandro Piccolomini's arguments with clear implications for the status of the mathematicians of the society. This strategy was countered by a rather intense campaign of Christopher Clavius, the architect of the program and the founder of a Jesuit mathematical tradition, who replicated some of Barozzi's arguments in his effort to buttress the position of the mathematicians. A certain climax was achieved, though, in the work of Josephus Blancanus who developed an ontology of mathematical entities in an attempt to ground the mathematical disciplines in a firm philosophical basis. In briefly reconstructing these three positions as strategies in the Jesuit politics of knowledge, my aim is to clarify the background against which Galileo's later rejection of the discourse on mathematical entities should be understood.

Perera developed his position in long passages of the widely circulated De Communibus Omnium Rerum Naturalium Principus, first published in 1576, and reprinted nine times until the end of the century.49 Departing from Piccolomini's suggestion that “quantity” inheres in prime matter as indeterminate extension independently of any substantial form, Perera securely anchored this contention in the Greek commentators and in Averroes.50 He thus deepened the ontological dimension of Piccolomini's thesis and inferred the fully consistent conclusions from it. Stressing the radical separation of quantity not only from sensible substances – as did Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas, and other Latin commentators51 – but from any substance, he then attempted to prove their complete disjunction from real physical or metaphysical essences. Quantity thus became fully extrinsic to form. Hence it was the most superficial dimension of things, easy to separate and abstract, although instrumental for understanding certain aspects of them. Perera illustrated his contention through the example of the mathematical property of the sphere touching the plane in one point only. Whereas this is true for the sphere as a mathematical – or abstract – extension, he argued, it is not true for the sphere as physical extension.52

Perera's rejection of the theory of mathematical “medietas” – adopted by Piccolomini from Proclus but interpreted in an Aristotelian sense as abstraction from sensible matter – was effectively carried out through an attack on the Platonic doctrine of reminiscence, essential for the idea that mathematical entities are innate in the human soul. God has given us a human soul that is “tabula nuda,” not inscribed with any contents and capable of learning all sciences, Perera argued.53 For if knowledge is truly acquired through reminiscence, how would one explain the necessity of the senses – which even the Platonists cannot deny? And if the senses are necessary for acquiring knowledge, then it is not possible to maintain the theory of reminiscience.54

Perera's radical rejection of the middle position of mathematical entities and his elaboration of the ontology of indeterminate extension as inhering in prime matter – independently of any substance – constitute his main contributions to the development of Piccolomini's position. If quantity was disconected from substance, then it had nothing to do with the explanation of causes, not even formal causes. Furthermore, Perera followed in the footsteps of Piccolomini denying mathematical demonstrations the status of a model for demonstration potissima and criticizing Euclid I, 32 as a non-causal and nonessential proof. Who cannot see, he argued, that the geometer proves the sum of the angles of a triangle equaling two right ones through a construction of the external angle, which cannot be considered a cause since it is completely accidental to the essential nature of the triangle.55

Perera's negation of the innate nature of mathematical entities together with his peculiar understanding of geometrical demonstrations led him to a clearer and more radical distinction between the certainty of mathematics, which he explains by its rigorous structure, accepting and even strengthening the arguments to substantiate it, and the scientificity of demonstrations potissimae, which are the only ones capable of treating real, material, physical substances and heading to true conclusions. Thus, in the order of the nobility of the sciences, mathematics was the most inferior, according to him, both because of the simplicity of its subject matter, and because of the kind of demonstrations it used. Moreover, the rigorous structure of mathematics secures its status as a discipline, but its objects and demonstrations excluded it from the realm of the sciences:

For the mathematician neither considers the essence of quantity, nor treats of its affections as they flow from such essence, nor declares them by the proper causes on account of which they are in quantity, nor makes his demonstrations from proper and per se but from common and accidental predicates. It is my opinion, that the mathematical disciplines are not proper sciences.56

No wonder that Perera's conception of the mixed sciences was completely instrumental. When the astronomer thinks of the magnitude, shape, form, and motion of the heavens, he is not preoccupied with true causes that explain the nature of things, Perera claimed, but with some reasonings that can save the appearances. This, according to him, was the nature of eccentrics, epicycles, some irregular motions of celestial bodies, trepidation, etc.57

The first chapter of Clavius's “Prolegomena” to his Commentary on Euclid's Elements58 reads as a direct and concise answer to Perera's arguments. First, he argued, the meaning of the word Mathesis in Greek was discipline, or doctrine, for only the arts of quantity used causal and potissimae proofs. The Pythagoreans and the Platonists believed that rational souls in some sense contained determined number, and therefore they could acquire these disciplines. Countering Perera's rejection of the theory of reminiscence, Clavius, quoting from the Meno, suggested that the process of remembering, was, in fact, a process of disciplining. This was understood by Plato in terms of a Socratic interrogation – which he exemplified in the story of Meno – and led to the ascent of the soul toward eternal truths. Clavius expressed a certain ambivalence toward Plato's theory, which presupposed, according to him, the migration of souls from one body to another – a possibility condemned as erroneous and false by Christian doctrine. Nevertheless, he massively relied upon quotations from Plato and from Proclus with which he became acquainted through the edition and interpretation of Barozzi. Following Barozzi too, however, he did not exclude Aristotle from his list of authorities, emphasizing the compatibility of mathematical disciplines with the canons of the Posterior Analytics and their rigorous structure – using only preknown principles and proved propositions – which justified their status as doctrine or discipline.59

Praising the nobility of the mathematical sciences in the third chapter, Clavius emphasized the certainty of their demonstration, which he contrasted with demonstrations practiced in the other sciences. Whereas those were incapable of actually demonstrating their claims (a fact resulting in endless unresolved disputations and in the plurality of philosophical sects) Euclid's propositions were unambiguous, and the certainty of mathematical demonstrations led to the pure truth.60 Clavius supported this contention with a quotation from Plato's Philebus, where the truth of geometry is connected to supreme goodness.61

Moving, in the fourth chapter of the “Prolegomena,” to the utility of mathematics, Clavius departed from their utility in administrating and governing the public sphere to their necessity for the study of all other disciplines. First he quoted Proclus showing how mathematics facilitated the passage from physical, sensible, and thus murky reality to the clear, enlightened reality of metaphysics.62 In Platonic terms, the passage from the sensible to the intelligible world was called ascent to the contemplation of divine things, and for this ascent the mathematical disciplines prepared the soul.63 Last, Clavius turned to the educational context, quoting both from Philebus and from the seventh book of the Republic, to stress again the necessity of mathematics as a basis for all other studies, as well as for leadership of political life in a city state.64

It is Clavius's strategy, throughout the “Prolegomena,” to indicate the basic agreement between Plato and Aristotle on the nobility, utility, and necessity of the mathematical sciences, even though their respective justifications may sometimes be formulated by different vocabularies or anchored in different philosophical world views. This means that the simple dichotomization between Platonists as lovers of mathematics and Aristotelians as ignorant in this realm did not hold true for Jesuits mathematicians,65 who refused to choose between Platonic and Aristotelian legitimation of their sciences, preferring to recruit both in the process of constructing their professional identity.

The controversy between Perera and Clavius represented in the hidden (but obvious) counterarguments of Clavius's “Prolegomena” testifies to the need of both philosophers and mathematicians to recruit ancient authorities for strengthening their positions. Plato and Aristotle were read and interpreted in accordance with contemporary needs, and their works functioned as imaginary constructions. Rather than a source of inspiration for mathematical innovation, they were used as topics for the symbolic capital contained in their figures.

In response to Piccolomini's and Perera's attempts to introduce a breach between mathematical entities and real, substantial forms, Clavius, relying upon Proclus's judgment, contended that the objects of mathematics, although considered in abstraction from matter, treated things immersed in matter. Adopting Barozzi's thesis of the medietas of mathematics he conceptualized mathematical entities as ontologically bridging between the complete abstractness of metaphysical objects and the full sensibility and materiality of physical ones:

Since the mathematical diciplines deal with things which are considered apart from any sensible matter, although they are immersed in material things, it is clear that they hold a place intermediate between metaphysics and natural science, if we consider their subject matter. For as has been rightly shown by Proclus, the subject of metaphysics is seperated from any matter, both from the point of view of the thing itself, and from the point of view of reason. The subject of physics is truly connected to sensible matter, from the point of view of the thing itself as well as from the point of view of reason. And since the mathematical disciplines consider their subject separately from any matter, even though it [matter] is found in the thing itself, it is established that they are intermediate between two.66

The chapter on the division of the mathematical sciences in Clavius's “Prolegomena” aimed at redrawing and broadening the traditional map of knowledge, to fit better the project of Jesuit mathematicians. In restructuring the field Clavius drew upon the argument about mathematical entities, being immersed in material things, although considered in abstraction from it. The Pythagoreans and quite a number of philosophers believed that the mathematical disciplines essentially consisted of four branches, each having a specific subject: arithmetics with discrete numbers, geometry with continous magnitudes, music with numbers in relation to voices, and astronomy with continous magnitudes in relation to the motion of celestial bodies. However, there was another division, anchored in the writings of other ancient authors – especially Geminus and Proclus, according to Barozzi's interpretation. The first considered mathematical entities as purely intellectual and absolutely seperated from matter. But in truth, mathematical entities belonged to things connected with matter.67 Without explicitly stating this, Clavius's juxtaposition of “intellectibles”versus mathematical entities immersed in material things seems to provide the justification for augmenting the number of mathematical diciplines concerned with physical phenomena to six, namely astrology, perspective, geodesy, canonics (music), suppotatrics (practical arithmetics), and mechanics, each being further divided into more specific branches.

There is a sense in which Clavius's practice of restructuring the map of knowledge can be derived from his (quasi)theoretical conception of mathematical entities as inherent in things immersed in matter. His theoretical arguement, however, was not anchored in any wide philosophical framework. Rather, it was an isolated insight, a reworking and reinterpretation of one passage from Proclus. His real justification came from the practice of mathematics itself. His elaborate descriptions of the various branches of knowledge pertaining to the physical world that have been successfully treated by mathematicians with mathematical methods was his proof. His insistence on the necessity and utility of mathematics for studying all other diciplines, which he supported with quotations from many ancient writers, Christians (St. Peter and St. Augustine) as well as non-Christians (Plato, Aristotle, Proclus, and others), was rheotrical by nature, based on repetition and accumulation of historical evidence, not on scholastic subtleties.68

More than anything else it is Clavius's style of arguing in many contexts, measured against what is known about his scientific career, that justifies the interpretation of the “Prolegomena” in terms of a cultural practice more than in terms of a philosophical justifications of the status of mathematics. His text comprised an attempt to restructure the map of knowledge so that more space be allowed for the discourse of mathematicians and thus deepening and stabilizing their authority compared to that of the philosophers. Departing from the Aristotelian premise that a science is defined by its specific subject matter, and by the kind of demonstrations it uses, he interpreted the nature of mathematical entities as a bridge between physical and metaphysical ones, being immersed in sensible matter and considered in abstraction from it. But although a boundary was thus created between natural philosophy and the mathematical sciences on the one hand, and between mathematics and metaphysics on the other hand (a boundary necessary for securing the autonomy of mathematics), Clavius's main strategy was to narrate the successes of mathematics in dealing with problems of the concrete physical world throughout history and in the present and to label anew as many mathematical subdisciplines as he could. Furthermore, although Clavius identified arithmetic and geometry as the two main mathematical fields of knowledge, he abstained from drawing too clear a boundary between pure and applied mathematics, suppressing the term “mixed sciences,” which he had used in his preface to Sacrobosco's Sphere.

Compared with Clavius's “Prolegomena,” Josephus Blancanus's “Treatise on the Nature of Mathematics”69 was a much more comprehensive attempt to rebut the attacks of opponents in an articulated, well-informed way, relying upon philosophical and metaphysical thinking of the period. Blancanus's text signals the crystallization of a meta-discourse among Jesuit mathematicians concerning the status of their field of knowledge and its justification.

Blancanus's point of departure, like that of Clavius's, was the subject matter of the mathematical disciplines, which he attempted to distinguish both from that of natural philosophers as well as from that of the metaphysicians. However, the content of his arguments differed substantially from that of his mentor. Recognizing Perera's contention that the subject matter of metaphysical discourse is quantity but rejecting Perera's judgement about the nonessential nature of that quantity and hence his denial of the status of mathematics as science, Blancanus defined a special kind of quantity called “delimited” or “finite” quantity (quantitas terminata), which he distinguished from Perera's “indeterminate quantity” (quantitas indeterminata). The entities considered by the mathematicians, according to him,

are entirely different from those that the natural scientist and the metaphysician consider in quantity absolutely…from this delimitation there result the various figures and numbers which the mathematician defines and of which he demonstrates various theorems.70

Drawing upon Clavius's insight that mathematical entities inhere in things immersed in matter, even though they are considered separately from it, but following much more closely Aristotle's own argumentation about the problem, Blancanus used the Aristotelian terminology concerning the abstract matter of mathematical entities which Aristotle had called “intelligible matter”:

But this [delimited quantity] is the quantity that is usually called intelligible matter, in contradistinction to sensible matter, which concerns the natural scientist, for the former is seperated by the intellect from the latter and it is perceived by the intellect alone.71

However, it was precisely because of the abstract nature of intelligible matter that mathematicians had been attacked for the nonexistence of mathematical entities. Blancanus answered to such a projection in the following terms:

… many [people] object to mathematicians that mathematical entities do not exist, except only by the intellect. However, we should know that even if these mathematical entities do not exist in that perfection, this is merely accidental… Therefore, even though these [perfect mathematical figures] do not exist in the nature of things, since in the mind of the Author of Nature, as well as in the human mind, their ideas do exist as the exact archetypes of all things, indeed, as exact mathematical entities, the mathematician investigates their ideas, which are primarily intended per se, and which are [the] true entities.72

To the contention of some philosophers that mathematicians use suppositions and argue in a mere accidental way, Blancanus responded that mathematical definitions were essential – not just nominal – and that only in mathematics is it possible to give definitions in which

the entire nature of the subject is primarily given to us: So it follows that the mathematical sciences proceed from what is better known to us as well as from what is better known by nature… And this is the reason why geometrical demonstrations are always so efficient and possess the highest degree of certitude.73

Arguing for the reality of mathematical entities and the essentiality of mathematical definitions constitutes the core of Blancanus's “apologia.” The certainty and scientificity of mathematical demonstrations stem naturally from the nature of the objects, which, he emphasized, no writer had ever doubted before Piccolomini, who had very few followers, nobody other, in fact, than Perera, Fonesca, and the Coimbran commentators. The rest of the tradition – Aristotelians and Platonists alike (and here Blancanus was following Clavius's narratological techniques) – all admitted that mathematical proofs were the strongest given in any science.

The implications of Blancanus's insistence on elaborating a sound “metaphysical” foundation for justifying the mathematical disciplines were uncertain from the point of view of the mathematicians’ politics of knowledge. No doubt Blancanus's “apologia” was a much stronger response to the philosophers’ critique than Clavius's pragmatic arguments. In Jesuit culture it could have meant a real resource for legitimation. However, Blancanus also tied up the fortunes of the mathematicians’ project to a philosophical discourse and to an ontology that would soon become obtrusive to major trends developing within the mathematics of his time, especially to the use of indivisbles and infinitesimals in the practice of mathematicians. One immediate effect of his vision was already apparent in his own text: The boundaries imposed in his treatise between mathematics and philosophy and between pure and applied mathematics were much more effectively constructed.

First we are going to discuss pure mathematics, i.e., geometry and arithmetic, which differs in kind from applied mathematics, namely, astronomy, optics, [perspectiva], mechanics and music. Quantity abstracted from sensible matter is usually considered in two ways. For it is considered by the natural scientist and the metaphysicians in itself… but the geometer and the arithmeticians consider [quantity] not absolutely, but insofar as it is delimited…74

This may have expressed the need to conform to the general policy of the Jesuit order, already implemented in the Ratio studiorum, which used the construction of boundaries as a strategy of control. In any case, the policy endorsed in Blancanus's text differed in nuance from Clavius's philosophically less committed solutions, which enabled both conformity with the policy of the order and maneuvering of the boundaries according to the needs of the mathematicians.

II. GALILEO'S MATHEMATICAL STRATEGIES: BETWEEN “MIXED MATHEMATICS” AND MATHEMATICAL PHYSICS

Galileo's early work should be read against the background of the debate on the certitude of mathematics and its appropriation by Jesuit mathematicians in the attempt to legitimize their ever broadening interests. The work on centers of gravity (Theoremata Circa Centrum Gravitatis Solidorum, 1585–7), the Bilancetta (1585–6), and even the project of De Motu (1590), which intended to combine Aristotelian dynamics with Archimedian statics, perfectly suited the spirit of the field of knowledge delineated by Jesuit mathematicians. As mentioned above, writing on centers of gravity was rather popular among mathematicians of the Jesuit Society, and at this stage Galileo was not exceptional in choosing this topic. Neither did Galileo's range of problems and applications exceed the realm of pure geometry. No attempt was made to cope with gravity in a physical sense or even with the effect of weight at different distances from the fulcrum. Rather, Galileo restricted himself to treatment of pure geometrical entities.

Slightly different was the case of Bilancetta, which used the theory of the lever and was concerned with its application to various practical problems. Here the objects of discourse were real and material, having weight and varying in volume and even in the medium in which they were immersed. In their different styles of arguing Galileo's first two texts corresponded to the two main directions in which Archimedes's work was received in sixteenth-century Italy: one axiomatic and purely geomatrical, springing from Archimedes's On the Equilibrium of Planes, and the other more physical, local, ad-hoc, and stemming from the discussion of On Floating Bodies.75

Galileo's project of studying motion as it emerged in the premature text of the De Motu, however, already transgressed, or even broke through, the boundaries between mathematics and natural philosophy which had only started to become a sensitive issue in the Jesuit politics of knowledge during the same years. Natural motions of terrestrial bodies were certainly not typical subjects of mathematical discourse in the last decade of the sixteenth century. At the same time, expanding the field of application of Archimedean models was not as unknown strategy.

Galileo's project consisted in an attempt to offer a unified explanation of all motions – natural up and down motions, as well as violent projectile ones – in mathematical terms, by using Archimedean models to cope with problems in the sphere of Aristotelian dynamics. Eventually this attempt failed to explain one basic feature of the motions, namely acceleration. Galileo tended to use one Archimedean model – the hydrostatic – to explain the difference in the velocities of bodies moving up and down as a difference between their specific weights in relation to the mediums in which they moved. At the same time he used the balance model to visualize the analogy between rest (equilibrium) and up and down motions and to experiment with the same body along differently inclined planes. The two models were not compatible, as the one considered specific weights, whereas the other dealt with absolute weights. Moreover, the full effect of weight on motion was not taken into consideration, as Galileo did not include in his balance model the distance of the weight from the center of the system. The velocity, in any case, came out of the theory as directly proportional to the body's (specific) weight. Hence, it could only be uniform. But that was incompatible with the facts known from experience.

Galileo proposed two ways of coping with this difficulty, which in retrospect read more as excuses for a failure rather than as real solutions to his problems. First, he suggested that acceleration was an accidental feature of motion, caused by the levity impressed in the body externally (either by the hand throwing a projectile or a property thought to be kept in the body from previous elevation) and intensifying its motion in its first stages.76 This explanation pushed him back to treating levity as a substance, not as a state relative to gravity, thus undermining his radical critique against the Aristotelian physics that was one of the main targets of the his text. But the second way of treating the supposed “accident” of acceleration was even worse, because it put in doubt the rationale of his whole enterprise. The direct proportion between the velocity of a body and its weight could not be observed by the one doing the experiment, Galileo claimed.77

In admitting his failure to identify the mathematical results expected from his theory in experience, Galileo, in fact, invoked the main objection to the scientificity of mathematics which had first been used by Piccolomini and entered the circles of Jesuit philosophers mainly through Perera. In the context of the complicated field of positions concerning the status of mathematics, and the arguments adopted by the different participants, Galileo's admittance of the difficulty of mathematical reasoning to capture processes pertaining to material objects could be read as a declaration of defeat.

Against this background, the project of his Mecaniche,78 seems as a return to the boundaries of mathematics accepted within the original discourse of the “mixed sciences,” neglecting the problem of natural motion and free fall and concentrating on a problem in the traditional realm of mechanics, namely, the force necessary to elevate a weight along planes of different inclinations. This force was now differentiated into two components: the weight of the body and the distance from the center of the system, expressed the body's inclination to fall. The inclination to fall – conceptually differentiated from gravitas by the term moment (momento) – was measured by setting two limits: maximum momento on the perpendicular plane and minimum on the horizontal plane. Thus, the law of the moment stated that moments on the inclined plane and the perpendicular plane related to each other as the perpendicular line is to the inclined line. Moment, then, was constructed as a purely geometrical entity.79

Following Galluzzi, I would like to emphasize that the Mecaniche embodies a different type of project than the De Motu: Unlike De Motu, Galileo's Mecaniche did not present a quest for a unified explanation of all motions. Rather, it was an attempt to ground the study of motion and build it upon mechanical foundations, rooted in the traditions of the “mixed sciences,” which acquired their renewed legitimacy in the environment of Jesuit mathematicians.80 This means that the question of velocity remained on the margins of the discussion, coming up either as an addition of momento to weight or as an effect of a force that was constant. Velocity, then, if discussed at all, could only be conceived as uniform velocity. Galileo's use of the term momento, however, points to the possibility of translating it into dynamical terms. Thus translated, the law of the moment would entail that in determinate periods of time the body would pass distances on the inclined plane that relate to the distances on the perpendicular like the inclined line is to the perpendicular. Still, because the velocity was conceived as a product of a constant force, the prominent fact of acceleration could not be integrated into this framework. That, probably, was the origin of the dead end that forced Galileo to go beyond his original association of velocity with constant forces and beyond mechanical motions toward a different type of mathematical analysis of natural motion.81

Galileo's split from the “mixed sciences” and his conscious attempt to create an alternative science of mechanics – which brought about his growing estrangement from the discourse of Jesuit mathematicians – will be illustrated, in this paper, by a detailed analysis of his treatment of local motion in some passages of the Dialogue (1632).82 Traditionally these passages have been read as an expression of the miraculous birth of modern science in Galileo's text, a reading that used to emphasize the break between Galileo's early and mature science, and obviously between the old and the new science. Recent readings, however, criticizing, developing, and documenting suggestions already made in the late nineteenth century have tended to stress Galileo's embeddedment in Aristotelian science.83 Whereas nineteenth-century historians such as P. Duhem discovered the continuity between Galileo's work and that of the fourteenth-century calculators, for example, contemporary historians have stressed his anchorage in the work of Jesuit philosophers and mathematicians.84 Continuing this last line of argument, my reading of selected passages of Galileo's Dialogue aims to represent, and interpret in a more contextual way, suggestions first made by Galluzzi in his Momento and then developed by Renn and others.85

In this reading, the attempt to broaden the discourse on mechanical motion by applying some of its concepts and techniques to the study of natural motion eventually led Galileo to a theory of acceleration in which weight was neglected as a cause and velocity moved into the center of discussion. But velocity was now thought of as the sum total of degrees of velocity, and it was represented geometrically by the infinity of parallel lines making up the surface of a geometrical figure. Thus, Galileo's project may be seen as an Aristotelian-Archimedean synthesis that violated the basic rules of both discourses. A reading of passages from the Dialogue in terms of this “problematique” is the focus of the second part of the paper.

As is well known, the first day of the Dialogue opens with a discussion of Aristotle's “general discourse upon universal first principles” (18), which leads, rather quickly, to a critical examination of his fundamental distinctions between two kinds of natural motions – along straight and circular lines – and also between two kinds of motions along straight lines: natural up and down motions on the one hand and violent motion on the other. Salviati raises many objections against this discourse, complaining that it seemed as if “he [Aristotle] was pulling cards of his sleeve, and trying to accommodate the architecture to the building instead of modeling the building after the precepts of architecture” (16) and that “whenever defects are seen in the foundations, it is reasonable to doubt everything else that is built upon them” (18). Suggesting that “basic principles and fundamentals must be secure, firm, and well established, so that one may build confidently upon them” (ibid.), he raises the reader's expectations for a foundational discourse built upon alternative “basic principles with sounder architectural precepts” (ibid.). What follows, however, does not really meet such expectations.

Every body constituted in a state of rest but naturally capable of motion will move when set at liberty only if it has a natural tendency towards some particular place; for if it were indifferent to all places it would remain at rest, having no more cause to move one way than another. Having such a tendency, it naturally follows that in its motion it will be continually accelerating. (20, my emphasis).

This passage opens a long digression from the critique of Aristotle that constitutes the major part of the first day to a modified, but still Aristotelian, discussion of accelerated motion, a digression in which Galileo's alternative is condensely presented for the first time. The passage consists of two statements: 1) The cause of motion is a natural inclination toward a place. 2) Natural motion is accelerated. In another famous passage in the Dialogue, Galileo reveals to the attentive reader that invocation of “nature” in scientific practice is always an indication for lack of explanation:

… we do not really understand what principle or what force it is that moves stones downward, any more than we understand what moves them upward after they leave the thrower's hand, or what moves the moon around. We have merely … assigned to the first the more specific and definite name “gravity” … and as the cause of infinite other motions we give “Nature.” (235)

In the light of this confession it looks as if the creation of an alternative mathematical science of motion involves resignation of the effort to suggest causal explanation either to motion or to acceleration. Instead, already at this early stage Salviati offers a conceptual analysis of the continuum that he applies to accelerated motion:

Beginning with the slowest motion, it [a moving body] will never acquire any degree of speed without first having passed through all the gradations of lesser speed – or should I say of greater slowness? For, leaving a state of rest, which is the infinite degree of slowness, there is no way whatever for it to enter a definite degree of speed before having entered into a lesser, and another still less before that. It seems much more reasonable for it to pass first through those degrees nearest to that from which it set out, and from this to those farther on. But the degree from which the movable body began to move was that of most extreme slowness, that it to say from rest. (21)

Salviati suggests that acceleration involves a continuous increase or decrease of degrees of speed (or slowness). Sagredo, however, demands an explanation to the obvious paradox (finally formulated by Salviati) such a description entails: How can a body pass infinite degrees of slowness (or speed) in finite time? Salviati tries to “solve” this difficulty by saying that “the movable body does pass through the said gradations, but without pausing in any of them” (20). This “solution” conceals a lifetime of reflection on problems of infinity, the continuum and indivisibles that Galileo could not settle. Used here as a strategy of excluding further discussion, Salviati, however, takes up the opportunity to make a very condense presentation of the core of Galilean innovations in the field of the new science of motion, stemming from his new conceptualization of impetus and from the choice to focus on acceleration as the central phenomenon of the analysis of motion.

This choice leads to the privileging of a few limited areas of research of local motion, especially the falling of a stone, namely, free fall, and the motion of a cannon ball, namely, projectile motion. Through a short discussion touching upon these subjects Salviati attempts to engage his hearers’ and interlocutors’ interest and consent by claiming the following:

(1) That free fall and projectile motion are accelerated or deccelerated. He acquires quick consent for this claim by translating his concepts of “acceleration” and “degrees of speed” (and slowness) into the well-known but poorly defined traditional terms of impetus and velocity: “Tell me,” he asks Sagredo, “if you have any trouble granting that the ball, in descending is always gaining greater impetus and velocity.” The obvious answer to which is: “I am quite confident of that” (22).

(2) That the impetus acquired in fall is enough to lift the falling body up to the same height from which it started falling. This is a much more problematic assumption, for which Galileo acquired a real proof only after publication of the Two New Sciences, but which he used as a postulate there. Here the claim is justified by pointing out experiments that could confirm it.

From these two statements Salviati concludes that two equal bodies falling from the same height, one in free fall and another on an inclined plane, will arrive with the same “impetus” – which we have seen him treating as synonymous with “velocity”:

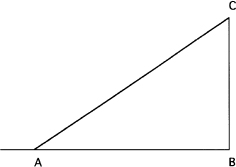

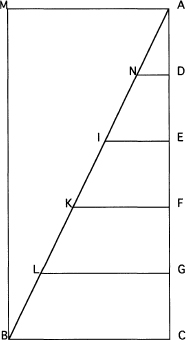

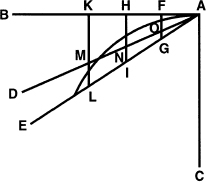

Figure 3.1.

So will you not put an end to your difficulty by conceding that two equal movable bodies, descending by different lines and without any impediment, will have acquired equal impetus whenever their approaches to the center are equal? (23, my emphasis)

Sagredo's difficulty in understanding the claim leads to Salviati's explication and to the use of a geometrical figure (see Figure 3.1) to represent free fall by the perpendicular and descent along the inclined plane by the oblique. The geometrical representation, serving here as a tool for clarifying the meaning of concepts,86 allows Salviati to try and disperse the ambiguity with which the term “impetus” has traditionally been stricken, and which still pervades Galileo's texts:

I ask you to concede that the impetus of that which descends by the plane CA, upon arriving at point A, would be equal to the impetus acquired by the other at point B after falling along the perpendicular CB. (23)

If before impetus and velocity were interchangeable, here equal impetuses seem to unambiguously mean that the two equal bodies acquire the same degree of speed upon arrival. Sagredo, however, responds by first conceding the conclusion, and then, bringing back the ambiguity: “In fact,” he says, “they have both advanced equally toward the center” (Ibid.). Equally in what sense?

At first it seems obvious that the claim about the equal impetus acquired at the point of arrival by the free-falling body and the body on the inclined plane entails that they both move with the same velocity. Salviati, however, takes this opportunity to point out a fundamental incompatibility between the two concepts of velocity – one deriving from Aristotle's Physics and the other from Archimedes,87 applied, however, to accelerated motions. According to the first definition of equal velocity – reiterated by Simplicio as equal spaces passed in equal times (24) – the body on the perpendicular moves faster than that on the inclined plane. According to the second definition – the equal proportion between spaces traversed and times elapsed – their velocities are equal. Salviati's explanation of this situation tends to calm down Sagredo's initially strong doubts. Still, he demands a real proof of the last conclusion, that the times of fall of both bodies relate to each other as the distances they traverse, which Salviati promises to supply from the mouth of his academic friend. Indeed, this had been Galileo's key theorem in his work on inclined planes. It is to be found in De Motu88 and has been labeled by some scholars as the length-time theorem.

Four statements concerning acceleration have been established by Salviati up to this point:

1) That free-fall motion and motion on the inclined plane are accelerated.

2) That the impetus acquired in accelerated motion starting from the same point suffices to lift the bodies to the same height.

3) That the impetus or degree of speed acquired at the point of arrival is equal for both bodies.

4) That the velocity of both bodies is equal according to an Archimedean concept of velocity.

Nevertheless, the claim for the continuity of acceleration made immediately afterwards goes back again to the Aristotelian concept of velocity, relying on the growing slowness of motion as the body moves on lesser and lesser inclined planes, until it comes to rest on the horizon. Yet, this is combined with an Archimedean argument according to which: the degree of velocity acquired at a given point of the inclined plane is equal to the velocity of the body falling along the perpendicular to its point of intersection with a parallel to the horizon through the given point of the inclined plane. (28)

The strong tensions characteristic of Galileo's discourse emerge even in this cryptic presentation of some of his major discoveries. The recognition (pointed out above89) of a gap in our knowledge concerning the cause of local motion and its acceleration seems to lead to the attempt to understand acceleration first on a phenomenological level: by a conceptual analysis of the continuum and the geometrical representation of continuous acceleration and by comparing different accelerated motions. This presentation, however, raises two fundamental problems. First, while Saliviati's argument is unfolding, its origins in the old mechanics understood as a “mixed science” crop up with greater clarity. They finally become evident in the following passage:

Let us remember that we agreed that bodies descending along the perpendicular CB and the incline CA were found to have acquired equal degrees of velocity at the point B and A. Now, proceeding from there, I believe you will have no difficulty in granting that upon another plane less steep than AC – for example, AD – the motion of the descending body would be still slower than along the plane AC. Hence one cannot doubt the possibility of planes so little elevated above the horizontal AB that the ball may take any amount of time to reach the point A. If it moved along the plane BA, an infinite time would not suffice, and the motion is retarded according as the slope is diminished. (27)

In Galileo's Mecaniche, the speed of motion depends upon the body's weight and on the distance from the center of the system, called the moment of weight. The same bodies, therefore, moving on lesser and lesser inclined planes, acquire lesser and lesser momenti. The way to measure this motion is by assigning maximum moment to the perpendicular and minimum to the horizontal. Therefore, the speed on the less inclined planes is considered smaller.

Salviati's analysis in the Dialogue suppresses the traditional mechanical considerations in terms of weight and moments of weight. It leaves the notion of velocity connected with this discourse, in spite of its basic incompatibility with the definition of velocity as the proportion of times elapsed and traversed distances, which is used in the attempt to convince us that the velocity of a falling body and that of a body moving on the inclined plane are equal. This example clearly shows that the decomposition of velocity into infinitesimal degrees presented at the beginning of the text and the substitution of the traditional Aristotelian definition of velocity with the Archimedean definition cannot in fact be conceptually truncated from the traditional discourse of mechanics, in which weight played a major role.

The same uncertainty is evident in Salviati's formulation of the comparison between two equal bodies, one free falling and the other moving on an inclined plane. Speaking about two equal bodies means that weight is considered relevant to the discussion. At the same time the main thrust of the argument points to the horizon of the constancy of “impetus” – that is, the increase or decrease of the degree of velocity – and the equal velocity of the two bodies according to the Archimedean definition. If the degrees of velocity acquired by two bodies in free fall and on the incline are always the same, and if their velocities are also the same, what is the relevance of their equal weight?

The second fundamental problem raised by Salviati's presentation concerns the decomposition of velocity into infinite degrees of velocity and its relation to the Archimedean definition of velocity as a proportion between times elapsed and distances traversed. In fact, decomposition of velocity means that the proportion is not between lines, but rather between infinite sets of points. Galileo, however, lacked the philosophical justification to deal with such proportions. Furthermore, the switch between velocity decomposed into infinitesimal degrees for conceptual analysis and the application of the Archimedean proportion has the effect of blurring the distinction between degrees of velocity and velocity altogether. Salviati's conclusion from the following two statements – that the motion downwards is accelerated and that the impetus gained suffices to lift the bodies to the same height – reads as follows:

Two equal movable bodies, descending by different lines and without any impediment, will have acquired equal impetus whenever their approaches to the center are equal.

However, the next two references to the same issue – “In fact, they [the free falling body and the one moving on the inclined plane] have both advanced equally toward the center” (23) and “the speeds of the bodies falling by the perpendicular and by the incline are equal” (24) – remain ambiguous. Such ambiguity bordering on the obscure, culminates in Salviati's summary, which reiterates both that the motion is slower as the inclination above the horizon gets smaller and simultaneously that:

We may likewise suppose that the degree of velocity acquired at a given point of the inclined plane is equal to the velocity of the body falling along the perpendicular to its point of intersection with a parallel to the horizon through the given point of the inclined plane. (28)

Simplicio's failure to understand this opaque formulation brings about Sagredo's last attempt at clarification:

Whence no doubt can remain that the ball [namely, a cannon ball projected upwards which starts to lose its velocity and continues with slower and slower motion until it stops] before reaching the point of rest, passes through all the greater and greater gradations of slowness, and consequently through that one at which it would not traverse the distance of one inch in a thousand years. Such being the case, as it certainly is, it should not seem improbable to you, Simplicio, that the same ball, in returning downward, recovers the velocity of its motion by returning through those same degrees of slowness through which it passed going up. (31)

At first glance it seems that Sagredo's explanation is based upon a complete nonsequitur. How is the continuous nature of acceleration connected to the need of the body to “recover” its velocity? In fact, however, this passage, coming from the mouth of Sagredo, testifies to the model of accelerated motion lurking in Galileo's mind, in spite of its being erased from the text. In this model acceleration is still considered as the effect of an external force that the body loses while going up (in the De Motu hydrostatic model it is called levity, in analogy to the loss of weight in a medium of smaller specific gravity) and that it regains while going down. In contradistinction to Salviati's arguments, in Sagredo's explanation the abstract mathematical considerations are substituted with a picture easy to imagine and clearly present to the senses, which appeals to Simplicio's discursive habits and squeezes his long-awaited consent: “This argument convinces me much more than the previous mathematical subtleties” (ibid.).

The second and last discussion of free fall in the Dialogue taking place on the second day exhibits a very similar structure. This time the digression is made in response to Simplicio's quotation from a recent book written by a Jesuit mathematician,90 who tried to calculate the velocity of a cannon ball falling from the orbit of the Moon to the center of the Earth. Salviati's quest to understand the rules underlying this calculation is met with the answer that the falling ball continues to move at uniform velocity equal to the motion along the Moon's orbit. Salviati's and Sagredo's sarcastic dismissal of this answer is followed by the presentation of alternative principles for analyzing the fall, and by an alternative calculation, including an explanation of the method by which it could be arrived at.

“The movement of descending bodies is not uniform,” claims Salviati, “but…starting from rest they are continually accelerated” (221). There follows a straightforward statement – missing in the previous presentation – of the law of fall, that is the exact mathematical ratio of acceleration: “The acceleration of straight motion in heavy bodies proceeds according to the old numbers beginning from one” (222). This acceleration is then explicitly said to be equal to all falling bodies, without any connection to their weight: “for a ball of one, ten, a hundred, or a thousand pounds will all cover the same hundred yards in the same time” (223).

To understand the principles of the cannon ball's fall from the orbit of the Moon, Salviati quotes one more theorem and some “conjectures.” The theorem he refers to is the “double distance rule,”91 which establishes the relationship between accelerated and uniform motions. In accordance with this rule the falling cannon ball would acquire a degree of speed equal to the velocity of a body uniformly traversing double the space at the same time (255). This means that the cannon ball whose motion was calculated by the Jesuit in fact moves much faster than he had claimed in his book.