WILLIAM SHEA

6 Galileo's Copernicanism: The science and the rhetoric

When Galileo left the University of Pisa without taking a degree in the spring of 1585, he was a promising young mathematician with an experimental bent, but there was nothing to foretell his later interest in astronomy. He earned his living by giving private lessons in Florence and Siena, and it is probably at this time that he wrote a short Treatise on the Sphere or Cosmography for the use of his pupils.

This elementary textbook of spherical astronomy is based on the thirteenth-century Sphere of John Holywood, better known under his Latinized name of Sacrobosco. It is conventional in its geocentrism and makes no mention of Copernicus. Galileo may have used it when he became a Professor of Mathematics at Pisa (1589–92) and during the first years of his professorship at Padua (1592–1610).

In Pisa, Galileo made the acquaintance of Jacopo Mazzoni, a philosopher who sought to combine the insights of Plato and Aristotle, and with whom he stayed in touch after he had left Tuscany for the Venetian Republic. It was this friend who, in 1597, provided Galileo with his first opportunity of stating his opinion that the heliocentric theory of Copernicus was more probable than the geocentric system of Aristotle and Ptolemy.

Mazzoni had just published a book in which he claimed to have found a new and decisive argument against the motion of the Earth. Taking for granted Aristotle's assertion that Mount Caucasus is so high that its summit is illuminated by the Sun for a third of the night, Mazzoni inferred that from the top of the mountain one could see two thirds of the celestial vault. Mazzoni then boldly concluded that if the Earth moved around the Sun, and hence shifted its position with respect to the stellar sphere, at least two thirds of the heavens would be visible in the course of a year.

Galileo immediately saw the flaw in his friend's reasoning and sent him a letter in which he used simple trigonometry to show that the revolution of the Earth around the Sun would not entail any difference in the number of visible stars.

Galileo's argument did not have an immediate impact on his contemporaries but it played a vital role in his personal development. Mathematics had been called upon to refute the latest argument against Copernicus and had emerged victorious. This was a considerable psychological boost for a junior professor who had yet to muster the courage to express his Copernican leanings.

A month later, Galileo proudly informed the German astronomer Johann Kepler that he had managed to account, on the Copernican hypothesis, for a number of natural events that could not be explained on the received geocentric doctrine. He added, however, that he refrained from publishing for fear of ridicule, which shows that he was not utterly sure of being right.

In this essay, we shall examine in the first part how Galileo's celestial discoveries confirmed him in the opinion that the Earth moves around the Sun; in the second part, we shall discuss the arguments that he presents in his literary masterpiece, the Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems; and in a concluding section, we shall contrast his method with that of his predecessors.

GALILEO'S CELESTIAL DISCOVERIES

The appearance of a nova in the autumn of 1604 caused a considerable stir among the students in Padua, and Galileo gave three public lectures to large audiences in which he explained that the absence of any apparent displacement of the new star against the background of fixed stars (what is technically called parallax) indicated that the new star had been produced beyond the lunar region, namely in that part of the world that the Aristotelians held to be immune from change. Copernicanism was not the issue; the debate revolved entirely on the Aristotelian doctrine of the immutability of the heavens.

Matters might have rested at this level of general conjecture had not something new occurred. The novelty did not descend from the ethereal regions of speculation. It was the mundane outcome of playing around with concave and convex lenses, in Italy around 1590, in the Netherlands in 1604, and in the whole of Europe by the summer of 1609. Out of a toy to make objects appear larger, Galileo made, first, a naval, and then a scientific instrument. In the Starry Messenger, which appeared in April 1610, he tells us how he heard of the telescope:

About 10 months ago a report reached my ears that a certain Fleming had constructed a spyglass by means of which visible objects, though very distant from the eye of the observer, were distinctly seen as if nearby. Of this truly remarkable effect several experiences were related, to which some persons gave credence while others denied them. A few days later the report was confirmed to me in a letter from a noble Frenchman at Paris, Jacques Badovere, which caused me to apply myself wholeheartedly to investigate means by which I might arrive at the invention of a similar instrument. This I did soon afterwards, my basis being the doctrine of refraction.1

The phrase “my basis being the doctrine of refraction” has sometimes been interpreted as though Galileo claimed to have worked out the properties of lenses the way Kepler was to do a year later in his Dioptrics. Actually Galileo's theory was more modest and, significantly, more empirical, as he himself makes clear:

My reasoning was this. The device needs … more than one glass … The shape would have to be convex … concave … or bounded by parallel surfaces. But the last-named does not visible objects in any way … the concave diminishes them, and the convex, though it enlarges them, shows them indistinct and confused … I was confined to considering what would be done by a combination of the convex and the concave. You see how this gave me what I sought.2

Rumors of the invention of the telescope probably reached Galileo in July 1609 when he visited friends in Venice to explore ways of increasing a salary that had become inadequate for an elder brother expected to provide dowries for two sisters. He received little encouragement from the Venetian patricians who controlled the University of Padua, but he had a flash of insight when he heard that someone had presented Count Maurice of Nassau with a spyglass by means of which distant objects could be brought closer. The Venetians might not see how they could increase his salary, but what if he succeeded in enhancing their vision?

When Galileo returned to Padua on August 3, his fertile mind was teeming with possibilities. By August 21, he was back in Venice with a telescope capable of magnifying eight times. He convinced worthy senators to climb to the top of a tower from whence they were able to see boats coming to port a good two hours before they could be spotted by the naked eye. The strategic advantages of the new instrument were not lost on a maritime power, and it suddenly became clear to all that Galileo's salary should be increased from 520 to 1,000 florins per year.

Unfortunately, after the first flush of enthusiasm, the senators heard the sobering news that the telescope was already widespread throughout Europe, and when the official document was drawn up it stipulated that Galileo would only get his raise at the expiration of his existing contract a year later, and that he would be barred, for life, from the possibility of subsequent increases.

This incident understandably made Galileo sour. He had not claimed to be the inventor of the telescope, and if the Senators had compared his instrument with those made by others they would have found that his own was far superior. Let the Venetian Republic keep the eight-power telescope! He would make a better one and offer it to a more enlightened patron. Better still, he would show that much more could be revealed not only on land and sea, but beyond the reaches of human navigation.

The Moon's new face

The telescope was pointed to the heavens; and for the first time the human eye had a close-up view of the Moon.

Galileo's reason for examining the Moon was probably to confirm a conjecture that he had made in a satirical book published under the pseudonym of Alimberto Mauri in 1606. The changes in the features of the lunar surface that can be seen with the naked eye had been adduced as evidence that there are mountains on the Moon. His eight-power telescope was sufficient to strengthen this hypothesis and by November 1609 he had a fifteen-power telescope that enabled him to set all doubt aside. By March 1610, he had devised an instrument that magnified thirty times.

Galileo's construction of the telescope was the result of ingenuity and inventiveness rather than theoretical know-how. To his dying day, he remained in the dark about the laws of optics that lay behind his success. But although he could not determine the magnifying power from the focal lengths of the concave and convex lenses as we do today, he found a practical and reliable method that bypassed geometrical considerations:

Now, to determine without great trouble the magnifying power of an instrument, trace on paper the outlines of two circles (or two squares) of which one is 400 times as large as the other, as will be the case when the diameter of one is 20 times that at of the other. Then, with two such figures attached to the same wall, observe them both simultaneously from a distance, looking at the smaller one through the telescope and at the larger one with the other, unaided eye. This may be done without difficulty, holding both eyes open at the same time, and the two figures will appear to be of the same size if the instrument magnifies objects in the said ratio.3

This simple technique gives us a good idea of Galileo's resourcefulness and his practical cast of mind.

A didactic problem

As we have seen, the first celestial object that Galileo observed was the Moon. The drawings that he published in the Starry Messenger were to transform existing knowledge about our satellite. They also give us a glimpse into the didactic problems that he faced.

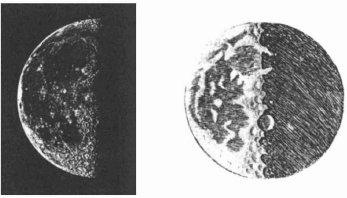

The illustrations of the Moon first and last quarter show a libration (apparent oscillation by which parts near the edge of the lunar disk are alternately visible and invisible) of 90 vertically measured from a crater (later called Albategnius) that Galileo chose to illustrate the shadow cast by mountains on the Moon. This feature enabled Guglielmo Righini to determine the date of the observations as December 3 and 18, 1609.4 A comparison of the Moon at last quarter as seen through a modern telescope and as sketched by Galileo reveals that the size of the crater is greatly enlarged in Galileo's drawing (see Figure 6.1).

Galileo noticed the difference between the illumination of the crater at first and last quarter, and he realized that this indicated that there were mountains on the Moon. He was anxious that this should not be overlooked by his readers, and like many good teachers, before and after him, he exaggerated the size of what he had observed in order to bring out the salient features. This was all the more necessary since, in a small woodcut, Galileo could not highlight the shifting pattern of shadows without giving the crater considerable width. There is no telescopic enigma here, just good pedagogy.

Figure 6.1. Moon at last quater, (left) as seen through a high-power telescope (Lick Observatory Photographs) and (right) as drawn by Galileo (from his Starry Messenger). (From Stillman Drake, Galileo at Work. Chicago University Press, 1978, p. 145).

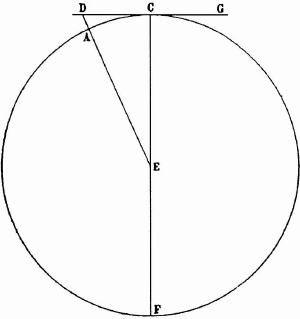

Figure 6.2. Diagram of the Moon with mountain of height AD.

The problem of communication comes to the fore again in the diagram that Galileo used to illustrate his trigonometric determination of the height of mountains on the Moon (see Figure 6.2). This shows a mountain AD whose peak is just touched by a ray of sunlight GCD. The rest of the mountain still lies in the dark region beyond the boundary of light CF. From his knowledge of the radius of the Moon (CE or AE) and his observational determination of the distance DC, Galileo arrived at the figure of four terrestrial miles for the height of the mountain AD.5

In October 1610, Galileo received a note from the German scientist Johann Georg Brengger pointing out that the phenomenon that Galileo recorded could not have been observed on the rim of the Moon for reasons that Galileo himself had clearly stated. Namely, the rim of the Moon appears perfectly circular, not toothed or dented, because the space between the mountains is concealed by other ranges of mountains. The illuminated spots in the dark region could only have been observed near the center. The unevenness of the boundary line between light and darkness made precise measurement impossible, but it seemed incontrovertible to Brengger that no more than three hours could have elapsed between the time of the first illumination of a peak in the darkened area and its joining the illuminated boundary. Because the Moon goes around the Earth (i.e., describes a circle of 360°) in roughly 29 days, in 3 hours it covers about 1°. This means that the distance CD (see Figure 6.2) is much shorter than Galileo claimed and, hence, that the mountain AD need only be one third of a mile high. A mountain four miles high would imply a rotation of 5° and a time of 8 hours, much more than Galileo had intimated.

In a lengthy reply, which is one of the first detailed discussions of the application of geometry to the new celestial data, Galileo granted that Brengger's reasoning was valid but claimed that some peaks are indeed illuminated more than eight hours before reaching the boundary of light. All that could be concluded was that mountains on the Moon are of varying heights! More interesting, perhaps, is Galileo's avowal that his data were taken from the central part of the Moon. He had to draw the mountain as though it were on the very rim of the Moon in order to make his geometrical point clear. Galileo did not distort his data; he merely bowed to the requirements of sound teaching.

Sharpening the image

The spherical and chromatic aberrations of Galileo's first telescope were such that they probably blurred the difference in appearance between stars and planets. Galileo also suffered from a problem with his eyes which caused him to see bright lights as irradiated with colored rings. He could improve his vision by peering through clenched fists, and it is almost certainly personal experience and not theoretical consideration that led him to stop down the objective lens of his telescope, as he explains in the Starry Messenger:

If we now fit to the lens CD thin plates, some pierced with larger and some with smaller apertures, and put now one plate and now another over the lens, as required, we may form at will different angles, subtending more or fewer minutes of arc, and by this means we may easily measure intervals between two stars separated by but a few minutes, with no error greater than one or two minutes.6

Galileo began placing a cardboard stop on the objective lens of his telescope early in January 1610. This greatly reduced the haziness of the image and the rainbow discoloration, but it did not drastically narrow the field of view as Galileo believed. Perforated plates could only reduce the field of vision if they were fitted not to the lens but well beyond.

Kepler discovered this when he used the telescope that Galileo had sent the Archbishop of Cologne. This was equipped with a “window” that Kepler removed only to find that the field of vision was barely enlarged. The device might not have narrowed the field as Galileo had surmised; it did something more important: It reduced the fuzziness around small bodies and made it possible to detect satellites.

The satellites of Jupiter

By January 1610, Galileo had considerably improved his telescope and his means of observation. His device now magnified twenty times, and the lenses were fixed at the ends of tubes in such a way that the one with the eyepiece slid up and down the one containing the objective to allow for proper focusing. The instrument was about a meter long and was mounted on a stable base to free his hands for drawing. Finally, the objective lens was partly covered with an oblong piece of cardboard.

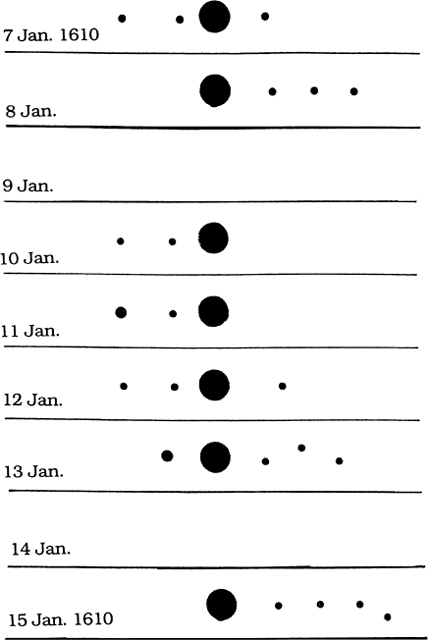

On the evening of January 7, Galileo saw three small but very bright stars in the immediate vicinity of Jupiter. The idea that they might be satellites did not occur to him. What struck him was the fact that they were in the unusual configuration of a short straight line along the ecliptic.

Looking at Jupiter on the next night, he noticed that whereas two had been to the east and one to the west of Jupiter on the previous evening, they were now all to the west of the planet. Again, he did not suspect that they might be in motion but wondered whether Jupiter might not be moving eastwards contrary to what the standard astronomical tables asserted.

On the 9th, the sky was overcast. On the 10th, he observed two stars to the east of Jupiter. This seemed to dispose of the conjecture that Jupiter might be moving in the wrong direction. On the 11th, he again saw two stars to the east of Jupiter but the furthest from the planet was now much brighter. On the 12th, the third star reappeared to the west of Jupiter. On the 13th, a fourth star became visible; three stars were now to the west and one the east of Jupiter. On the 14th, the sky was again overcast, and on the 15th, only three remained to the west (see Figure 6.3).

By the 11th, Galileo had concluded that the three stars he had observed were moving but he probably did not think that they were circling Jupiter, but oscillating back and forth along a straight line. Under these circumstances, it is impossible to point to an instant in time and say, “At this hour, he saw the satellites for what they really were!”

Galileo himself probably found it difficult to remember the genesis of his discovery from the first observation of three stars in the neighborhood of Jupiter to the full realization that they were satellites. But why was this discovery so exciting? Galileo tells us himself:

Here we have a powerful and elegant argument to quiet the doubts of those who, while accepting without difficulty that the planets revolve around the sun in the Copernican system, are so disturbed to have the moon alone revolve around the earth while accompanying it in an annual revolution about the sun, that they believe that this structure of the universe should be rejected as impossible. But now we have not just one planet revolving around another; our eyes show us four stars that wander around Jupiter as does the moon around the earth, and that all together they trace out a grand revolution about the sun in the space of 12 years.7

To those who objected that the Earth could not orbit around the Sun without losing its moon, Galileo could now point to the skies and show Jupiter circling around a central body (be it the Earth, as they believed, or the Sun, as Copernicus argued) without losing not one but four satellites. If Galileo could not explain why the Earth did not shed its moon, the Aristotelians were equally at a loss to say why Jupiter held on to its satellites. From challengers, the geocentrists were rapidly becoming the challenged!

Figure 6.3. Jupiter and its satellites.

From time immemorial, no new planets had been sighted, and Galileo saw that the satellites of Jupiter could be made to serve not only a terrestrial but a mundane cause. Anxious to ingratiate himself with the Grand Duke of Tuscany, he named the new “stars” Medicean after the family of the reigning Prince, Cosimo II. He was suitably rewarded by being recalled to Florence in the summer of 1610.

The Mother of Love and Cynthia

The satellites of Jupiter were the last of Galileo's discoveries in Padua. Shortly after his return to Florence, Venus, Saturn, and the Sun provided more celestial news.

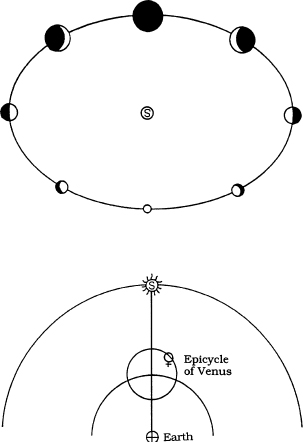

Among the difficulties raised against Copernicus's theory was the fact that Mercury and Venus, like the Moon, should display phases since they lie between the Sun and the Earth. Copernicus had replied that the phases were invisible to the naked eye, and Galileo was anxious to see whether his telescope would enable him to see them. Venus was usually too close to the Sun to be observed and it was only in the autumn of 1610 that he was able to confirm that Copernicus had been right.

At the time, anagrams were frequently used to guarantee the priority of a discovery without having to rush into print. On December 11, Galileo wrote to the Ambassador of Tuscany in Prague and enclosed the following mock sentence for Kepler: “Haec immatura a me iam frustra leguntur o y.” Kepler made a number of attempts to find the hidden message but he had to give up and wait for Galileo's letter of January 1 to learn that the letters, once transposed, read: “Cynthiae figuras aemulatur mater amorum,” namely, “The mother of love (Venus) imitates the appearances of Cynthia (the Moon).”8

The point is the following: If Venus revolves around the Sun, it will not only go through a complete series of phases, but it will vary considerably in size. At its greatest distance from the Earth, it will be seen as a perfectly round disk, fully illuminated. As it moves toward the Earth it will grow in size until at quadrature (corresponding to the first and third quarter of the moon) it will be half-illumined. At its closest to the Earth, it will have become invisible (like the Moon when it is new).

Figure 6.4. Venus in the Copernican and the Ptolemaic systems.

This is exactly what Galileo observed. Such a phenomenon would be impossible in the Ptolemaic system where Venus is said to move on an epicycle attached to a larger deferent circle whose center always lies on the line that joins the Earth to the Sun. Because Venus never goes behind the Sun, the complete sequence of phases is ruled out in this system (see Figure 6.4).

The discovery of the phases of Venus was a powerful argument against the ancient astronomy but it did not supplant the rival hypothesis of the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, who agreed that Venus and Mercury and all the other planets went around the Sun but maintained that the Sun itself revolved around the Earth.

The ears of Saturn and the sun's spots

Since Jupiter had four “assistants,” it was natural that Galileo should examine the other planets to see whether they also had satellites. He searched for many months in vain.

The result was a disappointment but it was also a source of complacency, for it was becoming clear that he was the only one whom God had predestined to discover new celestial bodies. Nonetheless, he was sorry not to be able to meet the request of the French Court which begged him to find a new planet and name it after their King Henry IV.

In the summer of 1610, however, Saturn presented an unsuspected aspect and showed itself as a conglomerate of three stars. Galileo, fearing that someone else might publish the news before him, immediately sent an anagram to the Tuscan ambassador in Prague, but he waited until November 13, 1610, before disclosing its meaning and offering the following information:

I have observed that Saturn is not a single star but three together, which always touch each other. They do not move in the least among themselves and have the following shape 000, the middle being much larger than the lateral ones.

Galileo went on to say,

If we look at them with a telescope of weak magnification, the three stars do not appear very distinctly and Saturn seems elongated like an olive, thus  . But with a telescope that multiplies the surface over a thousand times (i.e., magnifies a little over 30 times) the three globes will be seen very distinctly and almost touching, with only a thread of dark space between them. A court has been found for Jupiter, and now for this old man two attendants who help him walk and never leave his side.9

. But with a telescope that multiplies the surface over a thousand times (i.e., magnifies a little over 30 times) the three globes will be seen very distinctly and almost touching, with only a thread of dark space between them. A court has been found for Jupiter, and now for this old man two attendants who help him walk and never leave his side.9

Galileo had barely send off his letter when the two attendants began to dwindle to the point of vanishing entirely by the end of 1612. With a fine sense of melodrama, Galileo commented upon their disappearance to his friend Mark Welser:

What can be said of so strange a metamorphosis? Were the two smaller stars consumed like spots on the sun? Have they suddenly vanished and fled? Or has Saturn devoured his own children? … I cannot resolve what to say in a change so strange, so new, so unexpected.10

But Galileo soon plucked up his courage and, in the same letter, conjectured that the two attendants would reappear after revolving around Saturn, and that by the summer solstice of 1615, they would not only be again visible, but more luminous and larger. When they reappeared they had the shape of “ears” on each side of Saturn, but soon they vanished again!

As was later discovered, Galileo had been observing Saturn's rings, which are sometimes at right angle to the line of sight and virtually invisible while at other times they are more or less slanted and can be detected. The so-called ears were the most visible parts of these rings, and they remained a mystery until Christiaan Huygens was able to identify them with a better telescope in 1656.

It was natural for Galileo to wish to explore the Sun as well as the planets, but he could not observe the flaming ball of the Sun for more than a fleeting instant without being blinded. A neutral blue or green lens could be placed over the objective of the telescope, or the glass could be covered with soot. But the best method was found by one of Galileo's former students, Benedetto Castelli, who had the idea of projecting the image of the Sun on a screen just behind the telescope. Galileo was therefore able to see clearly the black spots on the surface of the Sun.

A Jesuit professor, Christoph Scheiner, who observed the sunspots at the same time, believed they were hitherto unknown satellites revolving close to the Sun. With geometrical rigor and devastating wit, Galileo was able to show that the spots lie on the surface or very near the Sun.

This was a momentous discovery at the time since, as we have seen, the Aristotelians maintained that nothing could change in the heavens, and surely not the eternal and immutable Sun! Galileo's discovery that devastating change occurred on the very face of the Sun was yet another blow to the traditional world view.

The decisive proof that the Earth moves

Galileo's celestial discoveries strengthened the case for Copernicanism but they fell short of being compelling. What Galileo wanted was a physical proof that the Earth moved. This proof eluded him for years but came to him in a flash on one of his frequent trips from Padua to Venice in a large barge whose bottom contained a certain amount of water that splashed up and down when the boat went faster or slower.

Galileo noticed that the water tended to pile up at the back of the boat when it accelerated and at the front when it slowed down. This struck Galileo as a kind of tidal motion, and he wondered whether the to and fro oscillation of the tides could not be explained by a combination of acceleration and deceleration. But where would the increase and decrease of speed come from?

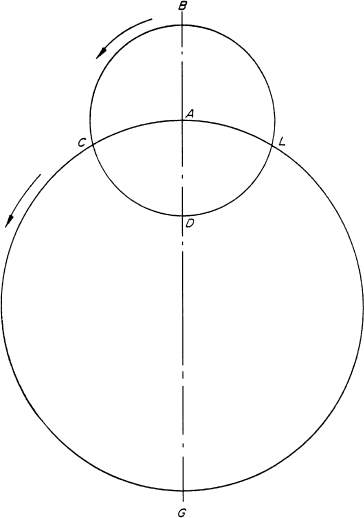

Galileo thought he had the answer. What if the speeding up and slowing down resulted from a combination of the diurnal and annual revolutions of the Earth! As befitted an astronomer used to describing the motion of bodies on epicycles and deferents, Galileo visualized the daily rotation of the Earth as occurring along the circumference of a small circle BCDL whose center A is attached to a larger circle ACGL that represents the annual revolution around the Sun (see Figure 6.5). The small circle revolves once every twenty-four hours. The axial and orbital speeds of the Earth are so combined that a point on the surface of the Earth moves very fast once a day when both revolutions are in the same direction (point B in the diagram) and very slowly once a day when they are going in opposite directions (at point D).

The land masses are not displaced by these combined motions, but the water in the oceans are tugged to and fro. If the Earth did not spin on its axis while it goes around the Sun, Galileo was convinced that “the ebb and flow of the oceans could not occur.”11

Galileo was so proud of his argument and so convinced of its power that he resolved to change the title of his book on Copernicanism from The System of the World, as he had provisionally called it, to A Dialogue on the Tides. He tried his argument out in Rome in 1616.

It was considered clever but unconvincing, and the fuss generated over the issue led the Roman censors to examine Copernicus's De Revolutionibus Orbium Caelestium, which had been published almost three quarters of a century earlier. The work was banned for claiming, without scientific proof, that the Sun was at rest in opposition to the commonsensical language of the Bible, which plainly speaks of the Sun (and not the Earth) as rising and setting. Galileo's writings were not mentioned and he even returned to Florence with a flattering testimonial from Cardinal Bellarmine, the Head of the Tribunal of the Inquisition, but he was bitterly disappointed and realized that it would be unwise to push the theologians too hard.

Figure 6.5. The daily and annual revolutions of the Earth represented by an epicycle on a deferent.

THE DIALOGUE ON THE TWO CHIEF WORLD SYSTEMS

Galileo had practically resigned himself to silence when, in 1623, Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, a patron of the arts, a poet, and a Florentine to boot, was elected Pope and took the name Urban VIII. At the suggestion of his friends in the Vatican, Galileo journeyed to Rome in the spring of 1624, and he was received six times by the Pope in the course of six weeks.

He failed in his attempt to have the ban on Copernicanism lifted, but he nevertheless derived the impression that he was free to write in support of the heliocentric theory as long as he “kept out of the sacristy” as a Roman prelate had advised him. Thus encouraged, he embarked, at the age of sixty, on his epoch-making Dialogue on the Two World Systems, which he completed in 1630 and saw through the press two years later.

Galileo chose to cast his argument for Copernicianism in the form of a discussion between three interlocutors. The two first, the Florentine Filippo Salviati (1583–1614) and the Venetian patrician Giovanfrancesco Sagredo (1571–1620), had been his friends; the third, the Aristotelian Simplicio, was an imaginary character.

They are presented as having gathered in Sagredo's palace at Venice for four days to discuss the arguments for and against the heliocentric system. Salviati is a militant Copernican, Simplicio an avowed defender of geocentrism, and Sagredo an intelligent amateur already half-converted to the new astronomy.

Never before Galileo had any critic of traditional astronomy been so apt at convincing an opponent by the sheer brilliance of his presentation, or so masterful at laughing him off the stage when he refused to be persuaded. Galileo drew from the literary resources of his native Italian to convey insights and to stimulate reflection, but his style does not possess the bare factualness of the modern laboratory report or the unflinching rigor of a mathematical deduction.

Words are more than vehicles of pure thought. They are sensible entities, and they possess associations with images, memories, and feelings. Galileo knew how to use these associations to attract, hold, and absorb attention. He did not present his ideas in the nakedness of abstract thought but clothed them in the colors of feeling, intending not only to inform and to teach, but to move and to entice to action. He wished to bring about nothing less than a reversal of the 1616 decision against Copernicanism, and the dialogue form seemed to him most conducive to this end.

Although the written dialogue may be deprived of the eloquence of facial expression and the emphasis of gestures and of the support of modulated tone and changing volume, it retains the effectiveness of pauses, the suggestiveness of questions, and the significance of omissions. Galileo made most of these techniques, and it is important to keep this in mind when assessing his arguments, for too often passages of the Dialogue have been paraded without sufficient regard for their highly rhetorical content. During the first three days the interlocutors debate astronomical issues; the fourth is devoted to a brief but powerful presentation of the physical proof from the tides that we have already considered.

The old world dismantled

The First Day of the Dialogue is devoted to a refutation of Aristotle's assumption that the sphere of the Moon divided the universe into two sharply distinct regions, the terrestrial and the celestial. Bodies in the celestial were said to be composed of a special kind of matter, the quintessence, which was incorruptible and underwent only one kind of change, uniform motion in a circle. Bodies below the Moon were subject to all kinds of change, and if they moved the motion natural to them was a straight line toward their proper place. Evidence for this view could be seen in fire which always moves straight up or in a clod of earth which always falls straight down.

To replace this double-tiered cosmos by the Copernican universe, Galileo had to show that the heavens are also subject to change. When the Aristotelian expert, Simplicio, states that the heavens are immutable because no change has ever been observed there, Salviati asks him how he can affirm that China and America are subject to change when he has only seen Europe. If the Mediterranean Sea was created, as many maintain, by water rushing in from the Atlantic through the straits of Gibraltar, the flood could have been noticed from the Moon.

But the Earth was obviously subject to generation and corruption before this happened. Hence why should the Moon not be equally corruptible even though humanity has failed to record any appreciable change? Indeed the novae of 1572 and 1604, and the sunspots, provide clear evidence that change does occur in the heavens.

Simplicio shifts his ground and denies that change makes sense on heavenly bodies,

which are ordained to no other use than the service of the earth, and need nothing more than motion and light to achieve their purpose, [for] we plainly see and feel that all generations, changes, etc. that occur on earth are either directly or indirectly designed for the use, comfort and benefit of man … Of what use to the human race could generations that might happen on the Moon or on other planets ever be?

This argument can be met either by denying that man is the center of all things or by postulating the existence of human beings on the Moon. Sagredo prefers to disclaim the anthropocentric assumption altogether. Although it is true that we can only imagine what we have already seen or what we can piece together from our past experience, we should not allow ourselves to be fettered by our limited knowledge when thinking on a cosmic scale.

Thus on the Moon, separated from us by such a great distance and perhaps made of a very different material from the earth's, it might be the case that substances exist and actions occur, not merely remote from, but completely beyond our imaginings.12

Galileo compares our speculations about the Moon to guesses that someone, who has never seen a lake or a stream, might make if he were told that animals move without wings or legs in a world made of water. Unless he were taken to a lake or shown an aquarium, he might indulge in the wildest fantasies without fear of disproof.

But if this is the case, and nothing can be proved, how can anything be disproved? What about the hard and impenetrable celestial matter of the Aristotelians? Galileo recognizes that it can only be ridiculed, as in the following witty exchange between Sagredo and Salviati.

Sagr. What excellent stuff, the sky, for anyone who could get hold of it for building a palace! So hard, yet so transparent!

Salv. Rather, what terrible stuff, being completely invisible because of its extreme transparency. One could not move about the rooms without grave danger of running into the doorposts and breaking one's head.

Sagr. There would be no such danger if, as some Peripatetics say, it is intangible; it cannot even be touched, let alone be bumped into.

Salv. That would be no comfort, for celestial matter, although it cannot be touched because it lacks tangible properties, can nevertheless touch elemental bodies, and it would injure us as much, and more, by running into us as it would if we had run into it.13

More interesting than Sagredo's and Salviati's devastating satire, is Simplicio's comment: “The question you have incidentally raised is one of the difficult problems in philosophy.” The question is, of course, perfectly sensible and legitimate in the Aristotelian framework, but it appears ludicrous in the new conceptual scheme. The world must not only be seen through the telescope, it must be looked at through a new set of intellectual categories.

The new world unveiled

Once the assumption that there is a radical difference between the terrestrial and the supra-lunar world is abandoned, what we know about objects on Earth can be used to know something about the Moon and the planets if they display phenomena similar to those with which we are familiar. Analogies can be brought into play to know what the lunar surface is like.

For instance, as Galileo points out, the suggestion that the Moon's surface is polished like a mirror must be discarded because the phenomena observed on the Moon cannot be reproduced with either flat or spherical mirrors. This can be achieved, however, by rotating a dark ball with prominences and cavities proportional in size to those on the Moon.

Out of the countless different appearances that are revealed night after night during one lunation, you could not imitate a single one by fashioning as you please a smooth ball out of more or less opaque and transparent pieces. On the other hand, balls may be made of any solid and opaque material which, merely by having prominences and cavities and by being variously illuminated, will display precisely the scenes and changes that are seen on the Moon from one hour to the next.14

Models are instruments, and if it is necessary to establish their relevance, it is no less important to determine when they break down. Simplicio brings the issue to the fore by asking Salviati how far he is prepared to extend the parallel between the Earth and the Moon. Would he be willing to say, for instance, that the large spots on the Moon are seas? Salviati replies with a brief lecture on models and analogies:

If the only way two surfaces could be illuminated by the sun so that one appeared brighter than the other was by having one made of land and the other of water, it would be necessary to say that the moon's surface is partly land and partly water. But because several other ways of producing the same effect are known, and there are perhaps others we are not aware of, I shall not make bold to affirm one rather than another to exist on the moon.15

Salviati is certain, however, that the darker parts are plains and the brighter ones mountain ranges because “the boundary which separates the light and the dark part makes an even cut in traversing the spots, whereas in the bright part it looks broken and jagged.”16

He is also willing to say that life on the Moon would be unlike anything known to us because of different climatic conditions. First, a lunar day is equal to a terrestrial month, and no earthly plant and animal could survive fifteen days of relentless and scorching heat. Secondly, the seasonal changes, which are considerable on the Earth because of a variation of 47° in the rising and setting of the Sun, are much less on the Moon where the variation is only 10°.

Finally, although oceans cover a large part of the terrestrial globe, the Moon must be waterless since it has no clouds. Sagredo suggests that this last difficulty might be overcome by postulating storms or great dews during the night. Salviati's reply is again instructive:

If from other appearances we had any indication that there were species similar to ours there, and that only occurrence of rain was lacking, we should be able to find something or other to replace it, as the inundations of the Nile do in Egypt. But finding no property whatever that agrees with ours of the many that would be required to produce similar effects, there is no point in troubling ourselves to introduce one only, and even that one, not from sure observation but because of a mere possibility.17

In Aristotelian physics, terrestrial models were deemed irrelevant because celestial bodies were made of an entirely different material. In Galileo's unified cosmos, analogies from familiar objects can be used to explain features of the Moon and the planets, but the limitations of this method are made clear. Galileo's caution is dictated by the prudence of the experimentalist for whom the world always hold surprises.

Every kind of change, for Galileo, is merely a reorganization of matter in motion. On this view, it becomes easier to know the course of the planets in the sky than the nature of generation and corruption on the Earth. The underlying assumption is that all bodies move in mathematically describable paths and arrange themselves in geometrical patterns. Although Aristotle was right in asserting that bodies are three dimensional, he should have proved his point instead of appealing to the consensus of the Pythagoreans and the fitting character of the number three:

I do not believe that the number three is more perfect for legs than four or two, nor that the number four is imperfect for the elements, and that they would be more perfect if they were three. It would have been better for Aristotle to leave these tropes to rhetoricians and to prove his point with rigorous demonstrations as is required in the demonstrative sciences.18

Simplicio expresses surprise and dismay. How can Salviati, a mathematician himself, ridicule the opinion of the Pythagoreans? Simplicio's astonishment serves a dual purpose.

First, it discloses the authoritarian frame of mind of the Aristotelian scholar, an intellectual stance Galileo is always eager to expose. Simplicio views disagreements as incidents between warring schools of thought. He thinks, and he assumes others do, as the member of a school, as the disciple of some ancient master. Secondly, Simplicio's reaction provides Galileo with the opportunity of distinguishing the Pythagoreanism of the mathematicians from that of the astrologers and the alchemists.

I know very well that the Pythagoreans held the science of numbers in high esteem, and that Plato himself admired the human intellect and considered it to partake of divinity simply because it understood the nature of numbers. I would not be far from making the same judgment myself. But I do not believe that the mysteries which caused Pythagoras and his school to have such veneration for the science of numbers are the follies that abound in the sayings and the writings of the common man.19

Salviati proves that bodies have only three dimensions by showing that no more than three lines can be drawn at right angles to each other. Simplicio initially fails to see the cogency of the argument because he lacks the elementary training that would enable him to think rapidly and consistently (a quality that can only be acquired by studying mathematics). “The art of demonstration is learnt by reading works which contain demonstrations,” says Salviati, who adds, “these are mathematical treatises, not books on logic.”20

This statement, which comes at the beginning of the First Day, sets the tone of the Dialogue. Galileo rejects the mystical number-juggling of pseudoscience, but he firmly believes that the human intellect partakes of divinity because it understands mathematics, the language of nature.

At the end of the First Day, when the use of mathematics has been vindicated in a variety of ways, Salviati returns to the theme of “divine” mathematical knowledge. The human mind is restricted in many respects, but it can attain certainty

in the pure mathematical sciences, that is, geometry and arithmetic, of which the divine intellect indeed knows infinitely more propositions, since it knows them all. But with regard to the few that the human intellect understands, I believe that its knowledge equals the divine in objective certainty, for it succeeds in grasping their necessity.21

The unity of all things in the mind of God “is not entirely unknown to the human intellect, but it is clouded in deep and thick mists.”22 The haze is dispersed when a mathematical proposition is so firmly mastered that it can be run over rapidly and with ease. What the divine intellect perceives in a flash, the mortal mind fits together bit by bit.

Galileo's concept of nature implies a revolution in the way we think about the world. Against the Aristotelians who dismiss mathematics as irrelevant and futile, he affirms that it is the divine feature of the human intellect. The implication is clear: For centuries, Aristotelians have ignored the divine principle in man. God is a geometrician in his creative labors. This is why Galileo declares in a letter to the Grand Duchess Christina that doubtful passages in Scripture should be interpreted in the light of science rather than the reverse:

It seems to me that in discussing natural problems we should not begin from the authority of scriptural passages, but from sensory experiences and necessary demonstrations. Holy Scripture and nature proceed alike from the divine World.… Everything that is said in the Bible is not bound by rules as strict as those which govern natural events, and God is no less excellently revealed in these than in the sacred pronouncements of Scripture.23

Galileo uses all the rhetorical gifts at his command to persuade his readers that science is not mere rhetoric. A few years earlier, he had written in the same vein against the Jesuit professor, Orazio Grassi (whose pseudonym was Sarsi):

I believe Sarsi is firmly convinced that it is essential in philosophy to support oneself by the opinion of some famous author, as if when our minds are not wedded to the reasoning of some other person they ought to remain completely barren and sterile. Perhaps he thinks that philosophy is a book of fiction created by one man, like the Iliad or Orlando Furioso (books in which the least important thing is whether what is written in them is true). Sig. Sarsi, this is not the way matters stand. Philosophy is written in that great book which ever lies before our eyes (I mean the universe) but we cannot understand it if we do not first learn the language and grasp the symbols in which it is written. This book is written in the mathematical language, and the symbols are triangles, circles and other geometrical figures, without whose help it is humanly impossible to comprehend a single word of it, and without which one wanders in vain through a dark labyrinth.24

The Second Day of the Dialogue will show that in the real world the Earth rotates on its axis; the Third Day will establish that it revolves around the Sun.

The diurnal rotation of the Earth

Galileo could not devise an experiment to prove that the Earth rotates on its axis but he could show that the traditional objections were no longer valid. For instance, it had been objected that if the Earth turned from west to east (instead of the Sun rising in the east and setting in the west), arrows shot to the west would carry further.

Sagredo suggests testing this by mounting a crossbow on an open carriage. What if an arrow that travels 300 yards when it is shot from a stationary crossbow were shot from a carriage that covers 100 yards in the same time? Simplicio, anxious to display his computational skills, immediately declares that it will travel 200 yards in the direction of motion and 400 yards in the opposite direction.

Salviati then leads him to the correct solution by pointing out that the speed could be equalized if the strength of the crossbow were increased in the first case and reduced in the second. This is, in fact, what happens since the crossbow shares the motion of the carriage. In the direction of motion, the arrow is given an impetus of 400 yards, and in the opposite direction it receives one of only 200 yards.

Since the carriage moves 100 yards during the time of the arrow's flight, the distances are equalized! The same holds for shots fired from a moving Earth: Regardless of the direction in which they are aimed, they will fall at the same distance from the mouth of the cannon.25

Galileo realized that vertical shots could be interpreted in the same way. Assuming that the Earth moves, a cannon ball shot straight upward will climb vertically while continuing to move horizontally at the same velocity as the rotating Earth whose motion it shares. Galileo's recognition that the vertical and horizontal motions are independent components represents a major conceptual advance. It was failure to grasp this principle that hampered his opponents and led them to believe that the impulse from the gunpowder would have to be added to that of the Earth's rotation.

If the Earth moves, its inhabitants share its uniform motion which therefore remains imperceptible to them. Ballistic experiments on Earth are of no avail.

The correct strategy is to call upon the heavens, to seek a motion common to all celestial bodies, and then to ask (in the light of the principle of simplicity) whether the phenomena could not be explained more profitably by postulating that the Earth also moves. Now clearly all the bodies that we observe in the heavens naturally move in a circle! It is legitimate therefore to consider the rotation of the Earth as something that is natural. Galileo's argument then takes the form of an appeal to simplicity:

Who is going to believe that nature (which by general agreement does not perform by means of many things what it can do by a few) has chosen to make an immense number of very huge bodies (i.e, the planets and the stars) move with incalculable speed, to achieve what could have been done by a moderate movement of one single body around its own center?26

The diurnal motion of the Earth would do away with a host of complexities in the geocentric system. First, it would remove the anomaly of a heavenly sphere of stars moving westward when all the planets move eastward. Secondly, it would explain the apparent variations in the orbits and periods of the stars, and, finally, it would dispense with the solid crystalline spheres that carry the stars around in the Ptolemaic system.

The motion of a stationary Earth is so firmly embedded in the imagination of the Aristotelians that when they hear that it moves they “foolishly assume that it started moving when Pythagoras (or whoever it was) first said that it moved.”27

The correct and indispensable procedure is to replace the Ptolemaic frame of reference by the Copernican one. If this is done, Galileo assumes, somewhat too easily, that all becomes clear, and he goes on to argue in the Third Day that the same can be said for the Earth's annual revolution around the Sun.

The annual motion of the Earth

The telescope made it possible to see that Venus has phases like the Moon, that the apparent diameters of Mars and Venus vary considerably, and that Jupiter orbits with not only one but four moons. Furthermore, because the telescope does not magnify the distant stars but reduces them to tiny dots, Tycho Brahe's fear that the stars would have to be gigantic in size becomes groundless.

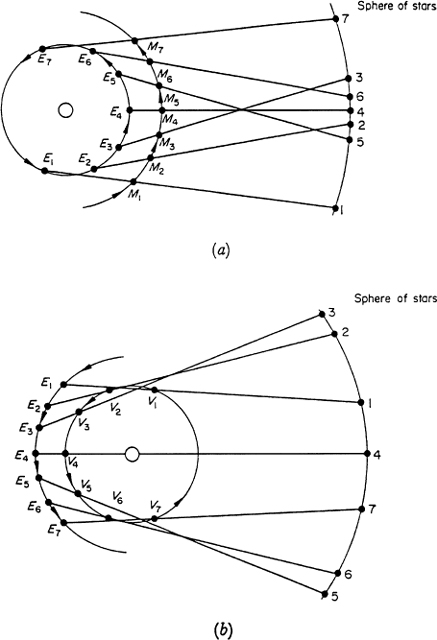

With the removal of these difficulties, Salviati claims that there is no longer any bar to admitting the Copernican hypothesis. Among other advantages, this nongeocentric view accounts for apparent irregularities in the motions of the planets without cluttering the heavens with deferents and epicycles as in the Ptolemaic system. In Figure 6.6(a), the sighting lines from the Earth, E, show why a planet farther from the Sun than the Earth such as Mars, M, seems to reverse its direction against the background of distant stars.

The retrograde motion is merely apparent and results from Mars traveling around the Sun more slowly than the Earth does. The motion of Venus, whose orbit lies between the Earth and Sun is explained on the same principle in Figure 6.6(b). This time the planet travels faster than the Earth. In the Ptolemaic model, these stations and retrogressions could only be explained by postulating an intricate series of deferents and epicycles. Such a complicated celestial machinery violated nature's basic laws, as Sagredo points out:

If the universe were ordered according to such a multiplicity, one would have to remove from philosophy many axioms commonly adopted by all philosophers, such that nature does not multiply things unnecessarily, that she makes use of the easiest and simplest means for producing her effects, that she does nothing in vain and the like.28

It is only with the heliocentric system, he adds, that the principle of uniform motion in a circle can be retained without filling the heavens with an intricate series of gears and wheels. Ideal physical proofs for Galileo should approximate geometrical demonstrations in rigor and simplicity. He praises Gilbert for his experimental work on the lodestone, but he cannot help wishing

Figure 6.6. The motion of an outer planet (a) and an inner planet (b) against the background of the stars.

that he had been somewhat better at mathematics, and especially well grounded in geometry, the practice of which would have made him more cautious in accepting as rigorous proofs the reasons he puts forward as the real causes of the conclusions which he himself observed. These reasons, candidly speaking, do not compel with the strength which those adduced for natural, necessary and eternal conclusions should undoubtedly possess.29

For want of mathematical training, otherwise intelligent people raise ridiculous objections against the motion of the Earth, asking, for instance, why they do not feel themselves transported to Persia or to Japan. Mathematics would sharpen their intellect and enable them to penetrate beyond the veil of the senses.

When Salviati lists the astronomical evidence in favor of the heliocentric theory, Sagredo is astonished that everyone has not embraced it yet. Salviati marvels rather that anyone should have upheld it prior to the invention of the telescope. Such a feat of intellectual daring is the hallmark of genius:

I cannot sufficiently admire the intellectual eminence of those who received it and held it to be true. They have by sheer force of intellect done such violence to their own senses as to prefer what reason told them over that which sense experience plainly showed them to be the case … I repeat, I cannot find any bounds for my admiration when I consider that reason in Aristarchus and Copernicus was so able to conquer sense that, in spite of it, it became the mistress of their belief.30

Aristarchus and Copernicus were unable to see the phases of Venus and the variations in the apparent diameters of Mars and Venus. Yet, “they trusted what reason told them and they confidently asserted that the structure of the universe could have no other form than the one they had outlined.”31

“What pleasure the telescope would have given Copernicus,” says Sagredo.

“Yes,” comments Salviati, “but how much less the fame of his sublime intellect among the learned. For we see, as I have already mentioned, that he persistently continued to affirm, assisted by rational arguments, what sense experience showed to be just the opposite.”32

CONCLUSION: REASON AND EXPERIMENT IN GALILEO'S PROCEDURE

For Galileo, the scientific revolution, the passage from the old to the new world-view, is not primarily the result of more and better observations. It is the inspired mathematical reduction of a complex geometrical labyrinth into a beautifully simple and harmonious system. The crucial distinction no longer lies between mental and factual but between mathematical and crudely empirical. Experiments (be they mental or real) are equally valid if they are set up in accordance with the requirements of mathematics.

Galileo replaces the qualitative approach of the Scholastics by a more rigorous method where measurement, at least in principle, becomes fundamental. When objects are not open to direct inspection, real or imagined models are invoked to determine the spatial and temporal relationships that are basic to scientific understanding.

Whether a stone dropped from the mast of a moving ship falls at the foot of the mast is a question that is settled by a thought experiment. We are asked to “observe, if not with our physical eyes, at least with those of our mind, what would happen if an eagle, carried by the force of the wind, were to drop a rock from its talons.” Salviati adds:

You will see the same thing happen by making the experiment on a ship with a ball thrown perpendicularly upward from a catapult. It returns to the same place whether the ship is moving or standing still.33

This is surely not an experiment that the captain of a ship would have welcomed! But even if Galileo had performed the experiment and had dropped balls from the mast of a ship, the issue would not have been settled. Aristotelians knew of the alleged result and remained not only impenitent but unperturbed. The margin of experimental error was too great, they said, for how could the mast remain straight as the ship rolled or pitched when pushed by the wind.

Galileo was conscious, however, that the results of mathematical reasoning must be open, at least in principle, to empirical verification. This was less important for his Aristotelian opponents, who viewed science in a different light. They accepted an instrumentalist interpretation of astronomy, and they considered explanations in terms of human purposes more real than explanations in terms of efficient causality which pointed the way to the regulative use of experiments.

The world, as they saw it, existed for man's enjoyment, instruction, and use; it was subordinate to him and made sense in relation to him. The realm of nature was not only Earth-centered but man-centered. It is largely a result of the Galilean revolution that many have come to view this attitude as a piece of intellectual arrogance.

The World and its purpose

The Middle Ages rediscovered and handed down to their successors a world vision inherited from the Greeks, whose main concern was not to seek out new facts but to provide an all-encompassing justification of world order. They were not interested in detailed explanation and prediction but in seeing how things formed part of a connected, rational, and aesthetically satisfying whole. Under the influence of Judeo-Christian theology, this led to the belief that the entire realm of nature was subordinate to man and to his eternal destiny.

There is a neatness and tidiness about this conception that is not only gratifying to the mind but pleasing to the eye. The imagination was left with an orderly picture of the world where each thing had its proper place. In time, this world-view acquired a deceptive obviousness which went unchallenged for want of a better alternative.

Man could, and did, marvel at the size of the universe, but he never doubted that it had been created for his use and benefit. Astrology was both popular and respectable because it was commonly assumed that human affairs would prosper when undertaken under the right conjunction of stars. Simplicio takes it for granted that the celestial bodies “are ordained to no other use than that of service to the earth.” He is boggled by the empty space the Copernicans wish to introduce between Saturn and the stellar sphere:

Now when we see the beautiful order of the planets, arranged around the earth at distances commensurate with their producing upon it their effects for our benefit, why go on to place between the highest orb, namely that of Saturn, and the stellar sphere an enormous, superfluous and vain space without any star whatsoever? To what end? For the use and convenience of whom?34

Under these rhetorical questions lies a method of philosophizing, indeed a philosophy of life. From this view, before one gets down to the details of building and testing the Copernican hypothesis, one must know whether it “stands to reason.” It is pointless to construct a new intellectual edifice, or even to examine its design, until its possibility has been ascertained.

It would be wrong to say that Galileo shirks the problem of man's privileged status in the cosmos or that it fails to impinge on his intellectual consciousness. Galileo claims that man's unique position does not derive from the fact that he occupies the spatial center of the universe but from his ability to encompass the entire world by grasping its mathematical structure. If we are to think in spatial images, it would be more appropriate to say that man's intellect goes around the universe than to describe him as sitting at the center of things.

Since what qualifies as a scientific explanation for Galileo is no longer an analysis in Aristotelian terms of act and potency, matter and form, but a mathematical theory verifiable in nature, he rejects the very concept of substantial change. In the new perspective, only “a simple transposition of parts” is amenable to mathematical treatment and, consequently, intelligible. The Aristotelians abuse themselves with words.

When Salviati is asked whether the motive force of the planets is inherent or external, he professes ignorance, but it is the ignorance of a Socrates who exposes the sham knowledge of those who claim to know. If his adversaries can tell him what moves the planets and the stars, Salviati will have found the force that moves the Earth. Simplicio replies that everyone knows that this is gravity.

“You are wrong, Simplicio,” says Salviati, “you should have said that everyone knows that it is called gravity. But I am not asking you for the name, I am asking you for the essence of the thing, and you do not know a bit more about that essence than you do about the essence of whatever moves the stars around.”35 All the Aristotelians offer are mere names for observed regularities.

Galileo, however, continues to think of natural motion as a tendency, an inclination, a natural instinct. The main objection to the diurnal motion of the Earth is solved by granting the Earth a natural tendency to revolve around the center of its mass once every twenty-four hours. In other words, the answer to the Aristotelians who suppose that the Earth is naturally at rest is to postulate that it moves naturally in a circle.

Galileo never formulated Newton's first law of motion, not because he was unwilling to postulate an infinite universe about which he remained uncommitted, but because he had to make circular inertia a cornerstone of his heliocentric system in order to answer the objections of his opponents. We see this in the way he conceives circular motion as a balance between force and resistance:

Acceleration occurs in a moving body when it is approaching the goal toward which it has an inclination, and retardation occurs because of its reluctance to leave and go away from that point; and since in circular motion the moving body is always receding from its natural terminus and at the same time moving toward it, therefore the reluctance and the inclination are always of equal strength in it. The consequence of this equality is a speed that is neither retarded nor accelerated, that is, uniform motion.36

This brings Galileo close to modern physics, but he never formulated the correct principle of inertia because he was thinking in terms of an eternally ordered motion. Because circular motion is natural, Galileo does not need a force acting on the planets to keep them orbiting. His great achievement remains his brilliant demonstration that the Aristotelian dichotomy between heavenly and terrestrial motion was not only wrong but stultifying and that the metaphysical barrier that precluded the presence of two natural motions in one body was no more than a mental block. Science and rhetoric won the day. Astronomy and physics could now forge ahead.

NOTES

1 Galileo Galilei, Starry Messenger, translated by Stillman Drake in his Telescopes, Tides and Tactics, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983, p. 19 (Nuncius Sidereus, Opere di Galileo, Vol. III, p. 60). On the telescopes that Galileo used, see Stillman Drake, “Galileo's First Telescopic Observations,” Journal for the History of Astronomy, VII (1976), 158–9, and his commentary in the form of a dialogue in Starry Messenger, pp. 19–21.

2 Galileo, Il Saggiatore, 1623, Opere di Galileo, Vol. VI, p. 259. I quote Drake's translation in his Galileo at Work, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978, pp. 139–40.

3 Starry Messenger, pp. 21–2 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. III, p. 61).

4 Guglielmo Righini, “New Light on Galileo's Lunar Observations,” in M. L. Righini-Bonelli and W. R. Shea, eds., Reason, Experiment and Mysticism in the Scientific Revolution, New York: Science History Publications, 1975, p. 75.

5 Starry Messenger, pp. 36–7 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. III, pp. 71–2).

6 Starry Messenger, pp. 22–3 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. III, p. 62).

7 Starry Messenger, pp. 88–9 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. III, p. 95).

8 Opere di Galileo, Vol. XI, p. 12.

9 Opere di Galileo, Vol. X, p. 474.

10 Opere di Galileo, Vol. V, p. 237.

11 Galileo, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (Ptolemaic Copernican) translated by Stillman Drake, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1962, p. 417 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 443). In this and in following quotations, I have sometimes amended the translation.

12 Dialogue, pp. 59–62 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, pp. 84–6). The reader interested in a general account of Galileo's life and works can turn to Annibale Fantoli, Galileo: For Copernicanism and for the Church, second edition, Vatican City: Vatican Observatory Publications, 1996.

13 Dialogue, p. 69 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 94).

14 Dialogue, p. 86 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, pp. 111–12).

15 Dialogue, p. 99 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 124).

16 Dialogue, p. 99 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 125).

17 Dialogue, p. 101 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 126).

18 Dialogue, p. 11 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 35). On science and rhetoric in the Copernican Controversy, see Jean Dietz Moss, Novelties in the Heavens, Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1993.

19 Ibid.

20 Dialogue, p. 35 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 60). See Maurice A. Finocchiaro, Galileo and the Art of Reasoning, Dordrecht and Boston: Reidel, 1980.

21 Dialogue, p. 103 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, pp. 128–9).

22 Dialogue, p. 104 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 129).

23 Galileo, Letter to Christina of Lorraine, Opere di Galileo, Vol. V, pp. 316–17.

24 Galileo, The Assayer, translated by Stillman Drake in Galileo Galilei et alii, The Controversy of the Comets of 1618, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1960, pp. 183–4 (Il Saggiatore, Opere di Galileo, Vol. VI, p. 232).

25 Dialogue, pp. 169–70 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 195).

26 Dialogue, p. 117 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 143).

27 Dialogue, p. 188 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 215).

28 Dialogue, p. 397 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 423).

29 Dialogue, p. 406 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 432).

30 Dialogue, p. 328 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 355).

31 Dialogue, p. 335 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, pp. 362–3).

32 Dialogue, p. 339 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 367).

33 Dialogue, pp. 143, 174 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, pp. 169, 200).

34 Dialogue, p. 367 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 394).

35 Dialogue, p. 234 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 260).

36 Dialogue, pp. 31–2 (Opere di Galileo, Vol. VII, p. 56).