PAOLO GALLUZZI

12 The sepulchers of Galileo: The “living” remains of a hero of science1*

Galileo died on January 8, 1642, in the unpleasant predicament of a man who had been condemned and then forced to abjure, as “vehemently suspected of heresy.” His will2 indicated that his remains should be placed beside those of his father Vincenzo and of his ancestors, in the Basilica of Santa Croce, where the family tomb can still be seen.

The death of such a remarkable person was not marked by solemn ceremonies or orations attesting either to his virtues as a man or to his sensational discoveries as a scientist and astronomer. On the day after his death, Galileo's body was removed to the Basilica of Santa Croce without the slightest hint of pomp or ceremony,3 accompanied by his son Vincenzo, by the Curate of S. Matteo in Arcetri, by Vincenzo Viviani, by Evangelista Torricelli, and by a few members of his family. The Grand Duke remained in Pisa, and no other important figures of Florentine public life made an appearance.

The furtive nature of the removal was a consequence of the fear that the ecclesiastical authorities might issue a formal interdict on the burial of Galileo's remains in the church of Santa Croce. This fear was not without grounds, as is demonstrated by a theological argument, almost certainly written at the request of the Grand Duke, in support of the legitimacy of the Christian burial of one vehemently suspected of heresy.4 It is extremely probable that the author was Giovanni Paolo Bimbacci, personal theologian of the Grand Duke and author of another contemporary argument, sustaining the absolute validity of Galileo's will.5

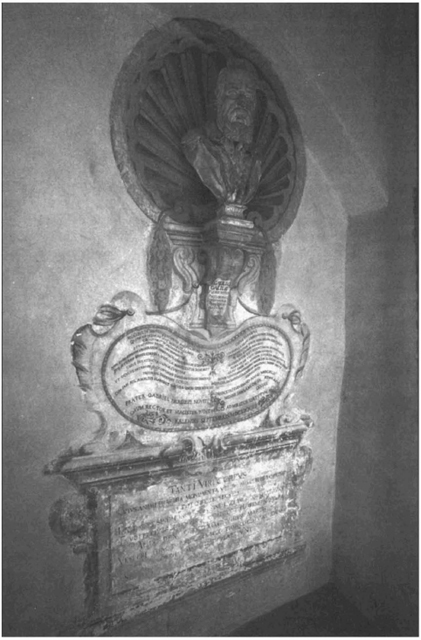

Given the circumstances, it was impossible to guarantee that all of the requests made by Galileo in his will would, in fact, be carried out. His mortal remains were not in fact placed in the family tomb. Fear of provoking the church authorities caused the family and disciples of Galileo to “conceal” the corpse in the tiny chamber under the bell tower of the church, access to which is, even to this day, by means of a small door on the left-hand side of the Cappella del Noviziato (Chapel of the Noviciate) dedicated to Saints Cosma and Damian (Figure 12.1).

Despite the fact that the burial process was carried out with extreme circumspection and discretion, the tender actions of the relatives and the disciples of the scientist were attentively observed and immediately reported to the Roman authorities. On January 12, 1642, the Florentine Nuncio, Giorgio Bolognetti, hastened to inform Cardinal Francesco Barberini, nephew of the pope, of the events following the death of Galileo and of the rumors in the city concerning the worrying proposals of the Grand Duke:

Galileo died on Thursday at 9 o’ clock: the following day his corpse was deposited privately in Santa Croce. It is said that the Grand Duke wishes to construct a sumptuous tomb, opposite that of Michelangelo Buonaroti in order to establish a paragone with him, and that he intends to entrust the Accademia della Crusca with the design of the model and the monument itself. With all due respect, I judged that it would be better for your Eminence to know this.6

The alarm bells had been sounded and Cardinal Barberini hurried to inform Urban VIII. A few days later, Francesco Niccolini, the Medici representative in the Papal See who had been an eyewitness to the trial and condemnation of Galileo, was called up before Urban VIII. As Niccolini reported to the Secretary of State of the Grand Duchy,

[the Pontiff] came to ask me to discuss a matter in confidence and only for his own business, not that I had anything much to write about; and it was that the Holy See had heard that the Grand Duke might have thought to have a tomb erected in Santa Croce. He wanted to tell me that it would not be a good example to the world for you to do so, as that man had been here before the Holy Office for a very false and erroneous opinion, which he had also impressed upon many others, there giving rise to a universal scandal against Christianity by means of a damned doctrine…7

Figure 12.1

The same day, Cardinal Francesco Barberini gave instructions to the Florentine Inquisitor. He was told that he should let it come to the

ears of the Grand Duke that it is not good to build mausoleums to the corpse of those who had repented before the Tribunal of the Holy Inquisition and who had died while in penance, because the good people might be scandalized and prejudiced with regard to Holy Authority.8

The combined dissuasive actions of the pope and his cardinal nephew produced the desired effects. On January 29th, Gondi, the Tuscan Secretary of State, reassured Niccolini:

There was much talk here too, of the tomb to the late mathematician Galileo, but without resolution, even in the mind of the Grand Duke. But, in any case, the considerations brought forward by Your Eminence about that which the Pope discussed with such delicacy will lead us to draw appropriate conclusions …9

The dream of the monumental tomb thus lasted only a few days: the remains of Galileo were destined to stay a long while in the narrow room attached to the Chapel of the Noviciate.

After this first rebuff, many years were to pass before the opportunity of erecting a monumental tomb to Galileo arose. The driving force behind this attempt to resuscitate the project was Vincenzo Viviani. He understood that the goal of bestowing sepulchral honor on Galileo was an essential part of the fight to promote the legitimacy and importance of Galileo's work and guarantee the liberty of Galileo's disciples to carry on his research and extend it to new fields. The image of Galileo as a heretic resulting from the 1633 trial obstructed the fulfillment of these objectives.

The rehabilitation of Galileo's reputation represented, for Viviani, not so much a defense of the Pisan from the insanity of his detractors and from many true or supposed usurpers of his discoveries, but, above all, an attempt at establishing the belief in the profound and unfailing Christian pietas of the Master. In the Life of Galileo of 1654, when dealing with the “incident” of the trial and the condemnation of the Dialogo, Viviani affirms that Galileo erred in not maintaining the presentation of the Copernican idea on a purely hypothetical level. For this error, the Church had rightly admonished him, and he had recognized his error and purged himself by a public and formal abjuration, in a fully sincere act of submission:

But, given that the fame of Sig.r Galileo had traveled even to the heavens through admirable speculations on other issues, and with many novelties which made him appear almost a divine being, Eternal Providence permitted him to demonstrate his humanity through error. Thus, in his discussion of the two systems he demonstrated himself to be more in favor of the Copernican System, already condemned by the Church as repugnant to Holy Scripture. For this reason Sig.r Galileo, after the publication of his Dialogues, was called to Rome by the Congregation of the Holy Office: where … by the highest clemency of that Tribunal and the Sovereign Pontiff Urban VIII … he was arrested and in brief (having publicly recognized his error) retracted, as a true Catholic, this opinion of his.10

This conciliatory thesis has been widely used by Catholic apologists up to this day to demonstrate Galileo's responsibility in the “affair” surrounding the trial. Viviani, however, adopted this position for purely instrumental reasons. To be convinced of this, one has only to consider Viviani's violent reaction in June 1678 when informed that the Jesuit Athanasius Kircher intended to include a eulogy of Galileo in his Etruria Illustrata11 in which the scientist was accused of not having proceeded with the necessary caution in the Dialogo and in his Copernican writings.

The analogy between such an interpretation and the presentation of the condemnation of Galileo in Viviani's Vita appears evident. Notwithstanding this, Viviani took immediate action, pleading with the Jesuit Father Baldigiani to exert every possible pressure on Kircher to persuade him to remove the statement about Galileo's imprudence from the eulogy, suggesting that this would also greatly please the Grand Duke, to whom the work was dedicated.12 Despite Baldigiani's reservations, Viviani continued to insist, until the Jesuit replied angrily that if he considered the circumstances with a modicum of objectivity Viviani would see that the tone of Kircher's eulogy for Galileo was anything but hostile:

He was summoned, interrogated and condemned: what could one say? That it was carried out in a state of complete innocence, that an entire Congregation was mistaken, that the most holy tribunal was unjust: who would ever speak in such a way, even if he believed it to be true? And even if he had spoken in such a way, how many would have been persuaded? Is it not better to say that he was mortified, that on those occasions he should have comported himself with more prudence, that he had caused injury to Urban VIII and the Barberini, and that they were justifiably irate.13

The line of conciliation assumed by Viviani aimed at removing force from the image of Galileo as a heretic, an image that clearly obstructed the propagation of the new science.

While conceding the fundamental point of the purely hypothetical value of the new science, Viviani was confident that he would be able to reopen a free space for research, which had been closed off since the condemnation of 1633. He never missed an opportunity to emphasize the moral dignity of Galileo and his exemplary conduct as a Catholic, ready to submit to the decrees of the Church. He reacted with heated indignation to the image, widespread outside Italy and especially in the Protestant countries, of Galileo as a “libertine,” unfettered by the dogmas of faith and thus both protagonist and martyr of the battle against the degeneration of the Roman Church.

This is shown by an extremely worried letter that Viviani wrote to Lorenzo Magalotti, then in Flanders, on July 24, 1673, asking him to intervene in order to prevent the forthcoming Amsterdam publication of the letters between Galileo and Paolo Sarpi.

… suddenly it came into my mind that if that were to happen, much material would be given to the perpetual detractors of Galileo, of which you know that there are whole regiments, to cause them to suspect that he was that which he certainly never was, not even in thought … I know that if I was in those parts, I would go straight to Amsterdam to see the letters for myself …, and, having seen them, whichever they turned out to be … I would not merely employ every skill and every possible means to impede their publication, but would also attempt to remove the originals and any existing copies, however great the cost…14

This strategy of conciliation was shared and encouraged by Grand Duke Ferdinand II and Prince Leopold. In order to continue to exploit the extraordinary celebratory potential of the protection given by Cosimo I and Ferdinand II to Galileo, and of the dedication of the satellites of Jupiter to the Medici dynasty, it was necessary to blur the conflict with the ecclesiastical hierarchy.

It seemed opportune to stimulate, on the one hand, the exaltation of the Galilean research tradition as an instrument particularly well suited to display the extraordinarily ordered structure of nature, an evident demonstration of the omnipotence of its Author. On the other hand, every care was taken to erase the intellectual trauma of the trial and condemnation of the Pisan scientist from the general memory.

When it was impossible to avoid mentioning the episode, it was stressed that although Galileo had erred, he had asked sincerely for forgiveness, expiring his last breath in the fold of the Holy Mother Church. In clear contrast with the image of Galileo the hero and martyr of libertas philosophandi, so widespread in Europe, and especially in France, the “Medicean” myth elaborated by Viviani presented Galileo as the promoter of a radical, but not traumatic, renewal of knowledge and as a man who respected the values and traditional disciplinary hierarchies, fully conscious of the relativity and transience of human knowledge.

Through a reduction of their cognitive significance, the results of the new science were “tranquilized.” The same purpose was served by the reductive experimentalism imposed on the Accademia del Cimento by the Medici princes.15 This emphasized the impossibility of man ever attaining full knowledge of the principles that determine the workings of nature. During the same period, it appeared crucial to repropose the major works of Galileo, especially the Dialogo, applying this new and reassuring interpretative key. Galileo's works were to be read not as sound evidence of the truth of the Copernican hypothesis, but as a demonstration of the unsurpassable limits of human understanding.

Finally, it became fundamentally important to give tangible form and full visibility to the image of Galileo as a Christian hero of science, whose faith had been reinforced by means of error, purified by sincere repentance and by a genuinely sincere act of submission to the Church. It appears evident that the erection of the tomb in the Basilica of Santa Croce represented a decisive step in this strategy. Thus, it is not surprising that the efforts carried out by Viviani to achieve the revocation of the prohibition of the Dialogo were inextricably bound up with his attempts to reopen the opportunity to erect a monumental sepulcher in the Basilica of Santa Croce.

The results obtained from his attempts to validate and promote the literary heritage of his master were relatively modest. In Florence, Viviani was responsible for the first complete edition of the works of Galileo. This was produced not in Florence, but by the Bolognese publisher Manolessi, undoubtedly to conceal Medicean support of the edition.16 Despite Viviani's labors, the edition, finally published in 1656, was full of errors and, necessarily, incomplete. Ecclesiastical permission for the insertion of the Dialogo and other Copernican writings was refused.

During the same period, Viviani did not miss an opportunity to affirm the importance of providing a decorous resting place for the mortal remains of Galileo. While waiting for this desired event, he devoted his attention to the preparations for the enterprise at hand. He had a clay model made from Galileo's death mask by the sculptor Antonio Novelli.17 He ordered Ludovico Salvetti to cast a bronze bust of Galileo with the aid of the model of Galileo's head that had been made by Giovanni Caccini around 1612, which has unfortunately been lost to us.18 Later, he commissioned Giovanni Battista Foggini, a friend of the scientist and the most enthusiastic “Galilean” artist, to sculpt a marble bust of Galileo.19 Viviani also asked Foggini to provide a rough sketch of the sepulcher for which the bust was destined.20 He carried out a successful petition to collect the necessary funds for the construction of the funeral monument,21 the symbolic and conceptual scheme of which he was busily working out in great detail. But the results of his efforts were disappointing. The project of the tomb was met with active opposition by the ecclesiastical authorities and the defenders of traditional intellectual culture.

When, in June of 1674, Paolo Falconieri, on behalf of Cosimo III, asked Viviani to provide him with a portrait of Galileo to serve as a model for a marble bust that the Grand Duke wished to place in the Gallery,22 Viviani seized the occasion to exhort Falconieri to remind Cosimo III of the far more ambitious wishes of his father Ferdinand II and of his uncle Leopold to give an honorable burial to Galileo.23 The noble and heartfelt peroration, however, went unheeded. Viviani's disappointment and discouragement are evident in his decision, taken some weeks later, to ornament Galileo's resting place with a bust and an epitaph exalting the merits of the deceased.

Evidence for Viviani's melancholy awareness of the futility of his efforts appears in many other events of the time. In December 1688, at the age of sixty-six, he wrote his will. This obliged his beneficiaries to carry out the project of realizing Galileo's funeral monument, which was to serve also as a resting place for his own mortal remains.24

With lucid and desperate determination Viviani went on to dedicate the last years of his life to the elaboration of every detail of the sepulchral monument. He reiterated that the monument had to be built in the Basilica, in symmetrical juxtaposition to that of Michelangelo. Like in the tomb of the great artist from Caprese, which was ornamented by three statues representing Architecture, Painting, and Drawing, three statues (Astronomy, Geometry, and Philosophy) were intended to stand guard over the relics of Galileo.25

Among Viviani's papers, numerous autograph versions of the inscription, which he intended for the sepulcher, have survived. These presented Galileo as a symbol of knowledge itself,26 emphasizing the admiration his works had elicited from literati the world over, who had frequently lamented the lack of a suitable funereal monument to the great scientist.27 Aware of the necessity of acting with extreme prudence if his project were to be approved, Viviani avoided any reference to the trial and condemnation of Galileo. The composition of the text of the epitaph for Galileo's tomb can be placed between the years 1691 and 1692.

In the same period, Viviani completed his final documented attempt to obtain a mitigation of the condemnation of Galileo, a fundamental prerequisite for the realization of the sepulcher. In an exquisite letter to the Jesuit Antonio Baldigiani of August 1690, Viviani made an able attempt to win the respectable father over to the noble cause of the rehabilitation of Galileo. The explicitly stated objective of the letter was to stimulate a priest well-versed in mathematics and the Consultor of the Holy Office, who had, on numerous occasions, expressed his deep admiration for Galileo, to use his position to obtain authorization to put the Dialogo back in circulation, with the corrections deemed necessary to restore to the work its character as an impartial illustration of two opposing conceptions of astronomy, both of which were defendable on a purely hypothetical level.28

Yet again, Viviani had been painfully overoptimistic. His request to treat Galileo's Dialogo on a par with Copernicus's De Revolutionibus was not accepted. Consequently, he decided to concentrate his efforts on a solemn “private” homage to his master, conceived, however, with remarkable originality, in such a way that it could be visible to the public.

Viviani had acquired a house in need of structural work on the Via dell'Amore (today Via S. Antonio) in Florence. He gave to his friend, the fervently Galilean architect Giovanni Battista Nelli, the task of transforming the facade of the palace into a structure documenting and celebrating the extraordinary intellectual achievements of Galileo. Giovanni Battista Foggini, to whom the bronze bust of Galileo which is still there to this day is attributed, also collaborated in the enterprise.29

Foggini designed the template for the tablets and was probably also responsible for the scrolls placed alongside the bust.30 The illustrations present in the two scrolls, based on the graphical model of medals, allude to Galileo's principal achievements in astronomy and mechanics. The two tablets of enormous dimensions placed on the sides of the main entrance, from which the name Palazzo dei Cartelloni (Palace of the tablets) is derived, bear texts of exceptional length for a commemorative epitaph.31

Thus conceived, the house was transformed into an extraordinary piece of propaganda, a memorial that was accessible to those passing, to whom Viviani made no casual appeal in the opening phrase: “passerby of upright and generous mind.”

The facade constituted the first memorial to Galileo visible in a public place in the city of Florence. It represented a sort of “lay” sepulcher to Galileo, pointing with implicit recrimination to the absence of a religious memorial. At the same time the tablets offered a conspicuous compendium of his works and life, conceived in accordance with the motivations of Viviani's strategy of reconciliation.

The tablet on the left gave abundant information about the details of Galileo's multiple conquests in the fields of astronomy, mechanics, and natural philosophy, emphasizing that the keystone of the extraordinary success of the Pisan scientist was to be found in the profitable union between geometrical analysis and experimental investigation which he had been the first to establish. Viviani listed the many celestial novelties discovered by Galileo with the aid of the telescope, but avoided every reference to the polemic de systemate mundi and to the dramatic conclusion of that controversy in the condemnation of 1633. In the final passage of the tablet, Viviani emphasized the moderation, and above all the piety of Galileo, “who had the greatest respect for God and Truth. The penetration by the depth of his mind of the stars, the sea and the earth is comparable only to that of God.”32

The tone of the tablet on the right-hand side was no different. This gave details of the fundamental events of Galileo's life. Regarding Galileo's birth in Pisa, to Vincenzo Galilei and Giulia Ammannati, Viviani insisted on the legitimacy of Galileo's conception and birth. He was concerned to refute the belief, propounded by Ianus Nicius Erythraeus (alias Giovanni Vittorio de’ Rossi33) and exploited by other authors, that Galileo was illegitimate. This bears witness to the importance, in the eyes of Viviani, of emphasizing the moral dignity and piety of the Master and is confirmed by the insistence, again in the right-hand tablet, of the Christian end to the life of Galileo.

The final years of Galileo are portrayed as the actualization of a design of Providence which, in order to allow the Pisan scientist better to perceive the magnitude of the Creator, deprived him of material vision. In preparing to abandon his earthly shackles, Galileo's conduct displayed the same exemplary degree of piety:

This great mathematician who had among his distinguished qualities a remarkable constancy, philosophical no less than Christian, strengthened by the repeatedly invoked spiritual help of the Church, rendered, in a most serene manner, his immortal soul to God.34

The addressee of the message inscribed on the second tablet was no longer merely the passerby, but the city of Florence itself, “cara Deo prae aliis urbibus.” Which other city could boast the privilege of having received from Providence, on the same day and at the same hour as the death of its celebrated son Michelangelo Buonarroti, reviver of the arts of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, the generous reparation of a new extraordinary hero, namely Galileo, perpetrator of the renewal of the whole of natural philosophy?

In acknowledgment of the privileged destiny bestowed upon her by Providence, Florence should express, by means of appropriate action, full recognition of the divine gift of these prodigious sons. The rhetorical device was, thus, a cautious, but nonetheless quite clear, means of publicly lamenting the lack of a sepulchral monument to Galileo.

Viviani's insistence on the coincidence of the death of Michelangelo and the birth of Galileo is striking. We must remember the news that circulated, just after Galileo's death, of Ferdinand II's intention to build a monument to him in Santa Croce “opposite that of Michelangelo Buonarroti, in order to establish a paragone with him.”35

The coincidence between the dates of the death of Michelangelo and the birth of Galileo which both occurred, according to Viviani, on February 18, was first put forward between 1691 and 1692, on the drafts of the epitaphs produced by Viviani, for the supposedly imminent construction of the sepulcher.36 In fact in the Vita of 1654, Viviani had established a chronological continuity and a comparison not between Galileo and Michelangelo, but between Galileo and Vespucci.37 Additionally, the Vita gave Galileo's date of birth as the 19th of February.38

During the course of 1692, while attending to the last changes to the texts for the tablets for the house of via dell'Amore, Viviani took great pains to establish the precise dates of Galileo's birth and of Michelangelo's death. From Pisa he obtained a copy of Galileo's original baptismal certificate, which bore the date of February 19. At the same time, he had confirmed with Baldinucci39 and Filippo Buonarotti40 that Michelangelo had died on February 18 at around 6 p.m. At this point, by assuming that Galileo was born the day before his baptism, the two dates were made to coincide perfectly.

The issue of continuity between the lives of Buonarroti and Galileo, represented, in Viviani's imagination, a guiding principle of the greatest importance.41 Viviani toyed with the idea of suggesting that a providential design had bestowed upon Florence the privilege of nurturing two great heroes, protagonists of radical renovation of the arts, in the one case, and of science, in the other.

His exaltation of the privileged role of the city recalled the magnificent patronage of the Medici dynasty, whose most important members had offered protection and amplification of the talents of these extraordinary celebrities. The subtle celebratory strategy which gave life to the Michelangelo-Galileo paragone was founded on the revival and extension of the well-tested cliché of the “Medicean” myth of Buonarroti.42 This myth had been constructed, mainly by Varchi and Vasari, immediately after the death of the great artist. It found eloquent expression, for the first time, in the somber trappings of the funeral rites conducted initially in 1564 in the Basilica of San Lorenzo and, subsequently, in the monumental sepulcher erected in Santa Croce.43

The Medicean Michelangelo displayed the combined countenance of a hero and a saint. In a remarkable distortion of his actual position and role as a defender of the Florentine Republic from the Imperial army, which brought the Medici back to power in Florence, he became the crowning glory of the propagandistic exercise, so dear to the heart of Cosimo I, to publicize the patronage and good government of the Medici.

Additionally, he was praised as a man perfectly in conformity with the Counter-Reformation canons of art as an effective instrument for the propagation and defense of orthodoxy.44 His whole intense existence, which also included a series of not entirely edifying episodes, was presented as a model of exemplary moral conduct and Christian piety.

To give plausibility to this complex and arduous operation, the authorities did not hesitate to cleanse the Canzoniere of the artist, of the more vulgar and earthly images it contained to render it more consonant with Christian ideals.45 Similar “corrections” were made to the provocative naked figures of the Giudizio Universale.”’46

Upon the death of Galileo, the idea of following, with the necessary adaptations, the model of the magnificent and advantageous Medicean celebration of Michelangelo must surely have occurred to Ferdinand II, and this was promptly seconded by Viviani.

In Galileo's case, celebratory emphasis on his harmonious synthesis of cultural and civil merit, on the one hand, and religious belief, on the other, was made increasingly difficult after the 1633 condemnation. For this reason, it was necessary to attempt to redefine the global significance of the Galilean program, according to the model that Viviani had outlined in his Vita of 1654. Galileo's piety had to be stressed above all other qualities, and his Copernican excesses in the Dialogo had to be seen to be redeemed by his subsequent repentance and abjuration. The abjuration itself represented, in Viviani's scheme, the highest and most emotionally charged testimony to Galileo's religious faith.

Thus, the heroic Galilean lesson was reshaped in consonance with Counter-Reformation ideals, in accordance with the model elaborated by Vasari and Varchi to construct the Medicean myth of Michelangelo.

It thus becomes clear why the construction of a Galileian sepulcher acquired such a deep significance. The veneration of Galileo's disciples for their master, the princes’ need to give public amplification to their role as protectors of an extraordinary genius, and the need to underline the continuation of Florentine cultural primacy under Medici direction, from the golden period of the Renaissance up to the present,47 all combined to reinforce the importance of a triumphal memorial. The falsification of Galileo's date of birth and the direct continuity so happily established between the lives of Galileo and Michelangelo gave new life to the image of a dynasty which, after having favored the rebirth of the arts by protecting Michelangelo, baptized the discoveries of new worlds and the birth of new methods and new sciences by supporting Galileo.

The image of the handing of the torch from Michelangelo to Galileo, established by Viviani, met with remarkable fortune. Among the many to reiterate the continuity was none other than Giovanni Battista Clemente Nelli, in his monumental Life of Galileo.

Nelli did have the courage to contest the additional happy coincidence established between the death of Galileo and the birth of Newton, the fruit of a much more brazen fabrication, which was, nevertheless, attested by numerous authors.48 Even Kant was moved by this distortion of the historical record, claiming that Michelangelo had been reincarnated in Newton, through the intermediary of Galileo.49

The construction of the Medicean myth of Galileo and the function that this had in the articulation of the project to erect a sepulcher in Santa Croce should not blind us to the other important factors and motivations at work in those who maintained a powerful bond between Michelangelo and Galileo. Despite the fact that Medicean mythcraft and clumsy Counter-Reformation amendments had substantially altered the original and tormented character of Michelangelo's religious spirit, the artist from Caprese remained the author of the Giudizio, a work that had perturbed many pious spirits by the overflowing and sensual nudity of its figures.

It was Michelangelo who had rebelled against Counter-Reformation canons, refusing to reduce painting, sculpture, and architecture to mere instruments of propaganda and defense of an orthodoxy rigidly determined by the ecclesiastical authorities. For his obstinate choice of freedom and for his unfettered articulation of his conscience he was not only discussed and criticized, but actually denounced and, especially after his death, heavily censored.

Michelangelo's true character, as a rebel against convention and the traditional models of knowledge, must have served to reinforce the comparison between the two celebrities among the disciples of Galileo. Both had been radical innovators in their cultural production and in the ways in which they interpreted the function and nature of religious feeling. Both suffered persecution and censorship for recklessly pursuing the truth.

From this point of view, the Last Judgment and the Copernican Letters offered multiple points of symmetry and analogy. Both works expressed, in their different genres and styles, intellectual experiences interwoven with a profound religious spirit. Both also met with the immediate and severe opposition of the ecclesiastical authorities.

It is, thus, difficult to remove the impression that what was at work in the persistent emphasis placed on the comparison by Viviani and the other Galileans was not only the calculated recasting of the Medicean myth of Michelangelo but also an awareness of a profound and objective symmetry between the two great and dramatic intellectual experiences.

Even in 1612, Ludovico Cardi, called Cigoli, had sown the seeds of this relationship by establishing a precise and suggestive comparison between Galileo and Michelangelo, based on emphasizing the common innovative character of their work, condemned precisely for this reason, faced with the incomprehension and opposition of the representatives of traditional culture. To comfort Galileo, who was worried about the discouraging reactions to his treatise Delle Cose che Stanno in su l'Acqua, Cigoli reminded him of the similar reception of the work of the great artist from Caprese:

As for the book you have printed, I heard from a man of letters that it was little to the liking of those philosophers; and, I believe, the same happened as when Michelagniolo began to design buildings outside the orders of the others up to his time, when all united to claim that Michelagniolo had ruined architecture by taking so many liberties outside of Vitruvius; I replied to them that Michelagniolo had ruined not architecture but the architects, because if they lacked designs such as his and continued to work as before, they appeared to be worthless things.50

The suggestion embodied in this comparison was continued even after the death of Viviani in 1703. Although he was not successful in his plan to build a monumental sepulcher to Galileo, by means of his will, he put into motion a mechanism that would be started as soon as the circumstances were favorable.

The auspicious moment was soon offered by a conspicuous series of attempts to promote the Galilean legacy, the key actors in which were a group of authoritative Catholic intellectuals, in the first third of the eighteenth century.51 At the forefront of a heated battle to modernize the Catholic Church, these people supported the abandonment of the traditional hostility that emerged in confrontations with new scientific and philosophical ideas.

These initiatives led to, among other things, the Florentine republication of the works of Galileo in 1718,52 which, however, still lacked the Dialogo and Copernican Letters, pending ecclesiastical authorization. The same desire to stress the importance of convergence between faith and the new Galilean science led to the publication of Torricelli's Lezioni Accademiche53 in 1715, and, more significantly, to the 1727 Florentine reprint of the complete works of Gassendi,54 a figure who assumed emblematic value, as a Galilean whose religious comportment was entirely beyond reprehension.

In the presentation and introductions of these editions the image of Galilean science as an intrinsically Christian doctrine was constantly reiterated.

After the death of Cosimo III, in 1721, the ferment of renewal and the attempts to revive the Galilean heritage underwent an acceleration and a slight shift in significance. The new Grand Duke, Gian Gastone, with the help of a group of powerful intellectuals, became involved in a courageous battle to circumscribe the enormous power of the Church and to restore full power to the State. His brief reign witnessed a number of extremely heated encounters between the ecclesiastical authorities and the Grand-Ducal functionaries. Many intellectuals trained by the Galilean professors at the Pisan Studio55 supported Gian Gastone's cause. Additionally, the proposals for reform of the Pisan studio made by the Proveditore Monsignor Gaspare Cerati drew support from similar considerations and conferred dignity upon the demand for full cultural and didactic recovery of the Galilean heritage.56

The Masonic phenomenon, the origins of which in Tuscany went back to 1735, presented itself as a movement animated by strong demands for cultural, scientific, and civil renovation and also adopted a clear and forceful anticlerical position.57 The influence of the new intellectual circles, which aimed to renovate not only the Studio of Pisa but also the academies and cultural institutions of Florence, and the determination with which Gian Gastone fought to secularize the State finally combined to elicit the appropriate moment for the erection of a sepulchral monument to Galileo. In those years, and in that intellectual climate, the realization of the old project acquired extreme political significance.

From a letter of June 8, 1734 from the Florentine Inquisitor, Paolo Antonio Ambrogi, to the Holy Office, we learn that he inquired to know if “there remained any order of the Supreme and Sovereign Congregation prohibiting the erection in this our Church of Santa Croce of a sumptuous tomb in marble and bronze in memory of the late Galileo Galilei.”58 The Consulters of the Congregation examined the case with extraordinary speed and decided, after deliberation, that the project would not be obstructed. It was recommended to the Inquisitor that he should ensure that the ceremony was not used to recriminate the ecclesiastical authorities. Moreover, he was required to approve the text of the epitaphs and of the official orations.59

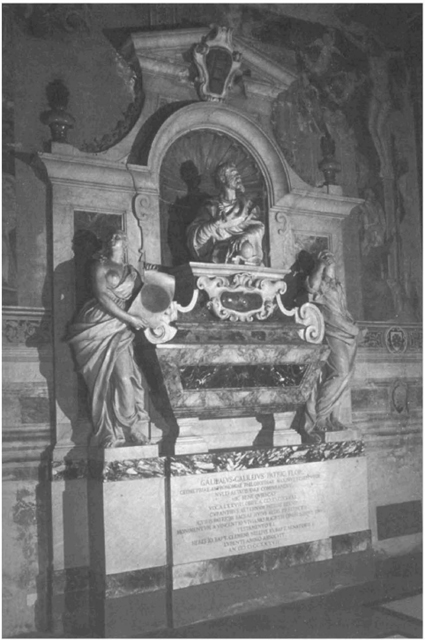

Documents giving further details of the realization of the project were missing until March 12, 1737, when the remains of Galileo were exhumed and transferred to the base of the new tomb, already nearing completion. The monument was finished on June 6 of the same year (Figure 12.2).60

It is clear that the operation represented a significant moment in the jurisdictional battle between the State and the Church. To bury the “heretic” Galileo with honors in Santa Croce, almost a century after his death, was an affirmation of the autonomy of the Prince from ecclesiastical power. The very way in which the ceremony was carried out and, above all, the people who played prominent roles confirmed that this was no mere act of pious homage, but an event of visible political significance.

The ceremony that took place on that memorable day in March 1737 is illustrated in detail in an Istrumento notarile (the Notary's official report), a public act that gives emblematic evidence for the official character bestowed upon the event.61 The Instrumento indicates with precision the composition of the official delegations charged with the solemn mission. The overriding criterion for inclusion seems to have been that of ensuring the most authoritative representation of the cultural institutions of Florence and of the entire Grand Duchy. Glancing down the list of delegates in the Instrumento, one is immediately struck by the lack of representatives of the ecclesiastical authorities.

Figure 12.2

Nonetheless, the cultural identity of the members of the official delegations is homogeneous and clearly characterized. Many of them, such as Antonio Cocchi62 and the abbot Antonio Niccolini,63 were known for their positions in the defense of the prerogative of the State, for the sympathies they displayed when dealing with progressive and materialist ideals, and, in particular, for the function they fulfilled in the Masonic circles of the city.

In the spring of 1737, there was already a violent conflict in progress between the Florentine Masons and the Inquisitor. This was to lead, a few months later, to the inquisition of the Mason Tomasso Crudeli,64 in the proceedings of which the names of many of the respected members of the delegation presiding over the exhumation and transfer of Galileo's corpse featured frequently, with explicit reservations about the solidity of their Christian faith.

Neither does it seem insignificant that in the proceedings of the trial the Florentine Masons were suspected not only of atheism and immorality, but also of being convinced Copernicans, that is to say, followers of the heretical Galileo.65 The identity of the notary Cammillo Piombanti is in tune with the general features of this group of intellectuals, and indeed he was himself very close to Masonic circles.66

From these remarks, it is evident that the fulfillment of the objective to which Viviani devoted much of his life occurred in an intellectual climate very different from that which saw its conception. Its significance, too, was modified profoundly in the new circumstances. Although Viviani had dreamed of a mutual embrace between the Church and a repentant Galileo, the 1737 ceremony became a challenge to the abuse of power by the ecclesiastical authorities who had long obstructed public homage being paid to the Pisan scientist.

Despite these changes, the new protagonists revived the central importance of the Michelangelo-Galileo comparison. The removal of the remains of Galileo to the new sepulcher actually took place on March 12, 1737 at 6 p.m. That is, on the same day and at the same time as the mortal remains of Michelangelo, in 1564, clandestinely brought to Florence from Rome, were solemnly deposited in the Basilica of Santa Croce, to await the erection of a tomb.67 This episode indicates the continued fascination that this comparison exerted, even in the new situation. It also reasserts that behind the juxtaposition of the two tombs in Santa Croce lay the desire to point out the symmetry and continuity between the two great men.

The precise limitations issued by the Holy Congregation with respect to the authorization of the construction of the Galilean tomb forced the promoters of the project to make certain compromises. It was, above all, decided to decorate the tomb with only two statues, of astronomy and geometry, and to abandon the original project of adding a third statue representing philosophy, which would have brought the tomb into full symmetry with that of Michelangelo. Caution suggested abandoning philosophy, which might have been considered an implicit reference to the realistic dimension of Galileo's Copernicanism. To avoid conflict with the Inquisitor and the Holy Congregation it was also decided to avoid making a solemn funeral oration.

On the evening of March 12, 1737, only the prudent epitaphs written by Simone di Bindo Peruzzi, Member of the Accademia Columbaria and Reader in the Tuscan language at the Florentine Studio, were permitted to be read out. In Peruzzi's first epitaph, later placed in the small chamber adjacent to the Cappella del Noviziato, it is at least possible to discern a reference to the dissatisfaction of citizens and foreigners for having had to wait nearly 100 years before seeing Galileo buried with due honor.68

The second epitaph, placed on the tomb in a very prominent position, displayed even greater prudence. It ended up more as a general homage to the Pisan, evasive about the details of his philosophical and scientific achievements, and entirely silent about the reasons why a recognition of these achievements in the form of a monumental tomb had not been given closer to the time of Galileo's death.69 The reticence of Peruzzi's inscriptions display that the Inquisitor, by whom the texts had to be approved, was closely guided by the mandate issued by the Congregation.

In the modest, yet intense arrangements for the March 12 ceremony, every detail was studied with meticulous attention. The Instrumento of the notary Piombanti indicates that a rigorous protocol was followed. To complete the monument required exhuming the bodies of Galileo and Viviani to enable their transfer to a position beneath the base of the sepulcher, already in an advanced phase of construction.

The Cappella del Noviziato was rigged out for the display of the bodies, to permit their public recognition, an operation that would have been impossible in the restricted space of the small chamber in which the original tomb was located. A great number of candles and torches, suitably positioned, allowed the crowd of bystanders to follow closely the different stages of the operation.

The Instrumento notarile describes how the operation began with the demolition of the brick tomb containing the remains of Viviani.70 A wooden coffin was removed from the tomb and taken to the Cappella del Noviziato. When the cover was removed, it was possible to see the remains of the last direct disciple of Galileo, as was attested by the inscription on the lead plate underneath the cover of the coffin. When the corpse had been identified, the coffin was placed inside a cask, draped in black, and carried to the new sepulcher in a solemn procession.

The ceremony was then repeated for the second tomb, on the left-hand side of the chamber, which was presumed to contain the mortal remains of Galileo. Following the same procedure, the brick tomb was taken apart. A wooden coffin with a broken lid emerged and “in removing [the cask], it was observed that immediately underneath it lay another wooden coffin of the same shape and size as the first, that is to say, capable of containing a human body.”

The detached account of the notary does not register the gasp of surprise the discovery must have elicited from the bystanders. None of those present was prepared for this find. The Instrumento notarile records only the series of actions carried out by the members of the delegation, after they had recovered from the initial shock, in order to deal with this embarrassing situation.

First, the upper coffin was removed to the Cappella del Noviziato, and its contents were examined. The corpse of an old man, “which had once been cut and opened, as was demonstrated by the anatomy professors present” was observed. The skeleton had fallen apart in many places, and the jawbone, which was detached from the rest of the skull, contained only four teeth. Next, the group proceeded to make accurate measurements of the skeleton.

At this point, the Instrumento registered a sense of panic that spread among those present:

In the view of all, a diligent search was made of the cask, amongst the remains of the clothing of the corpse, on the interior and exterior parts of the cask and among the bones removed thence, but no trace was found of any letters or characters or any other record of any kind.

The examination of the contents of the third and unexpected coffin assumed a crucial importance at this moment. Once again, the Instrumento, in detailed and clinical prose, describes the accurate examination of the corpse by the anatomy professors who also availed themselves of the knowledge of anatomical proportions of the professors of sculpture present that evening. The unanimous verdict that they came to was, fortunately, reassuring. The coffin contained the remains of a young woman who had died long ago. It was not possible to establish her identity, but her gender was enough to guarantee that the other corpse was that of Galileo.

Everybody breathed a sigh of relief. If the result of the examination of the remains of the third cask had been more equivocal, the ceremony which had been planned with such care would have turned into an atrocious farce. Once the identity of the remains of Galileo had been verified, the procedure that had been carried out with Viviani's remains was repeated. This time, however, the cask was borne to the new sepulcher only “after it had been displayed for long enough to allow the spectators to satisfy themselves with the sight of the revered bones of such a great man.”

For the organizers of the ceremony, the initial surprise on discovering the third mysterious cask must have been quickly followed by dismay on finding that the coffin supposed to contain the remains of Galileo lacked any sign to confirm the identity of the corpse. The intensity of this emotion can be seen in the decision of those present to remain silent about the event, fearing that any comments could lead to substantial doubts about the full success of the operation.

Even the slightest shadow of a doubt about the identity of the corpse transferred to the new tomb could have produced embarrassing consequences. Thus, all of those present agreed to forget the traumatic experience and to avoid inquiring as to the identity of the woman who had died at a young age and ended up under the coffin containing the remains of Galileo.

Many of the witnesses subsequently described the solemn ceremony of that evening while systematically avoiding mention of the unfortunate surprise, to avoid nourishing the doubt, malicious or otherwise, that the man who was being celebrated had not, in fact, been present.

That evening, the witnesses saw what was convenient to see, erasing from their memories any details that could have jeopardized the plan that had inspired the solemn display. As for the unobjective notary, Piombanti, it must be added that he did not even record the macabre rite of loving appropriation of fragments of Galileo's remains, carried out by the same authoritative members of the official delegation.

As can be deduced from indubitable and convergent testimonies, Antonio Cocchi, Anton Francesco Gori, and Vincenzio Capponi removed no less than three fingers, a vertebra, and a tooth from the decrepit remains of the Pisan, with the aid of a knife provided by Targioni Tozzetti.71 One of the fingers, placed immediately after the event in an urn inscribed with a solemn epitaph by Tomasso Perelli, is still preserved in the collection of the Institute and Museum of the History of Science of Florence,72 while the vertebra removed by Cocchi constitutes one of the most precious Galilean “relics” at Padua University.73

No doubt the notary, Piombanti, felt that this excessive expression of devotion to Galileo, considered as a saint whose relics were endowed with extraordinary evocative powers, could damage the image of the solemnity and decorum of the ceremony that the Instrumento was intended to portray.

However, Piombanti was not the only person to transform the events of that magical night for his own purposes. In the embellished account of the exhumation and the examination of Galileo's body, written many years later, Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti stated that

the face of the corpse had been preserved extremely well and in very close resemblance to the bust made by Gio. Caccini in the year 1610 from life … and to the portrait painted around 1636 by Monsieur Giusto Substerman, with that fine big sweeping head.74

The need to remove the memory of the anxious uncertainty of the identity of the corpse, by means of the highly improbable alleged resemblance to the iconographic records, induced Targioni Tozzetti to transfigure the bare and unrecognizable skull described accurately in Piombanti's Instrumento into a florid face with a penetrating gaze.

Even the accounts of the ceremony of March 12, 1737, written many decades later, maintained the character of the early reports. In his Vita of Galileo of 1793, Giovanni Battista Clemente Nelli gave substantial coverage of the solemn ceremony of 1737. He too considered it ill-advised to mention the little surprise that had animated the evening's proceedings. He published the entire text of Piombanti's Instrumento, taking care to omit the part describing the discovery and examination of the third corpse.75

The systematic cover-up operation surrounding this episode was so successful that it went completely forgotten. Nobody has felt the need to go back to the original Instrumento still preserved in the Archivio di Stato. Thus its “censored” version contained in Nelli's Vita of Galileo has been the only one consulted. No one has, therefore, taken the trouble to enquire further as to the identity of the woman in question, nor to wonder about the reasons for her singular and mysterious place of rest.

Let us pause to reflect on the facts. The cask containing Galileo's remains was found in the small chamber adjoining the Cappella del Noviziato. It had a damaged lid and was full of plaster fragments, which seemed to have been there for a very long time.

This suggests that, at a certain point, the brick tomb that had been built on Galileo's death in 1642 had been demolished to insert the second coffin. In the process of dismantling the tomb, pieces of plaster presumably broke the lid and penetrated the coffin. A number of clues suggest that the original tomb was opened in the summer of 1674, at the very time when the original tomb was decorated and adorned with the bust of Galileo and Viviani's laudatory inscription.

When the present arrangement of the small chamber adjoining the Cappella del Noviziato is examined with care, it can be seen that in 1737, after the tomb was demolished, its imprint remained on the wall, acting as a frame for Peruzzi's inscription. The frame is two braccia [a little less than four feet] in height, corresponding exactly to the height indicated in Piombanti's Instrumento. Above the frame, the epitaph placed there by Father Pierozzi in September 1674 stands with perfect graphical symmetry.

These observations suggest that the original tomb was transformed into a container with two levels at the same time as the decorations to the tomb were performed in 1674. If this were indeed the case, it comes almost naturally to the imagination to suppose that Viviani, wishing to carry out an act of profound devotion and sincere love towards his Master, had devised the touching idea of reuniting him with the remains of his favorite daughter, Sister Maria Celeste, whose burial place has never been identified.

Virginia, as she was known before taking the veil, had been very comforting to Galileo during the traumatic months of his trial, and her unexpected death in April 1634 was the cause of extreme and profound grief to the Pisan scientist. It was probably in this way that a desire expressed by Galileo on his deathbed was finally carried out in secret. The decision to bury the body of the unidentified woman in the monumental tomb indicates that it must have occurred also to those attending the ceremony on March 12, 1737, that they were in the presence of a person who had been very dear to Galileo.76

In the absence of direct documentary evidence, this must remain as a hypothesis. However, it is tempting to believe that in the long and complex story of the attempts to erect a tomb to Galileo, constantly marked by cynical political stances, by vested interests in celebrating Galileo's career, by compromises inspired by opportunism, and, finally, by continuous and significant distortion of his thought, the desire to carry out an act of pure love and compassionate solidarity, at least on one occasion, played its part.

NOTES

1 This essay is a shortened and revised version of “I sepolcri di Galileo. Le spoglie ‘vive’ di un eroe della scienza,” published in Il Pantheon di Santa Croce a Firenze, ed. L. Berti, Florence: Giunti, 1993, pp. 145–82.

2 Galileo Galilei, Le Opere, Edizione nazionale, ed. A. Favaro, 20 vols., Florence: G. Barbèra, 1890–1909 (henceforth EN), XIX, pp. 522–34 (second will, drawn up on the 19th November, 1638).

3 Ibid., p. 558, n. 6.

4 Ibid., p. 559–62.

5 Ibid., pp. 535–7.

6 EN XVIII, p. 378.

7 Ibid., pp. 378–9 (letter of January 25, 1642). On January 23, the Congregation of the Holy Office too, had discussed this delicate problem (see “I documenti del processo di Galileo,” ed. Sergio M. Pagano, Pontificiae Academiae Scientiarum, Scripta Varia, 53, Rome, 1984, pp. 239–40).

8 Ibid., pp. 379–80.

9 Ibid., p. 380.

10 EN XIX, p. 617.

11 Unfortunately this work is lost.

12 “If you delete these few words (that [Galileo] should have been more cautious etc.) the Great Duke will be very pleased” (A. Favaro, Miscellanea Galileiana imedita, Memorie del Reale Istituto Veneto di Scienze Lettere ed Arti, xxii, 1882, p. 829).

13 Letter from A. Baldigiani to Vincenzo Viviani, 12th July, 1678 (ibid., pp. 837–8).

14 Ibid., pp. 809–10.

15 For an analysis of the motives that persuaded the Medici Princes to promote the Accademia del Cimento, see my “L'Accademia del Cimento: ‘gusti’ del Principe, filosofia e ideologia dell'esperimento,” in Quaderni Storici, 48 (1981), pp. 788–844.

16 On the Bologna edition of the works of Galileo (Opere di Galileo Galilei … in questa nuova edizione insieme raccolte e di vari trattati dell'istesso autore non più stampati accresciute, 2 vols., Bologna, for the heirs of Dozza, 1656), see A. Favaro, Amici e Corrispondenti di Galileo, XXIX. Vincenzio Viviani. The whole series of Amici e Corrispondenti has been reprinted by P. Galluzzi, 3 vols., Florence, 1983, III, pp. 1106–8. See, also by Favaro, “Documenti inediti per la storia dei manoscritti galileiani nella Biblioteca Nazionale di Firenze,” Bullettino di Bibliografia e di Storia delle Scienze Matematiche, XVIII (1885), pp. 1–230. Cf. also Le Opere dei Discepoli di Galileo, Natl. Ed. edited by P. Galluzzi and M. Torrini, Carteggio, 2 vols., Florence: Giunti, 1975, II, pp. VIII–XII and the vast number of letters relating to the Bologna edition.

17 On the busts of Galileo, see A. Favaro, “Studi e ricerche per una iconografia galileiana,” Atti del Reale Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, A. A. 1912–1913, vol. LXXII, second part, pp. 1035–47; cf. also Giovanni Battista Clemente Nelli, Vita e Commercio Letterario di Galileo Galilei … 2 vols., Florence: Moücke, 1793, I, pp. 867–74. Amongst recent contributions, one should consult the excellent work of Frank Büttner, “Die ältesten Monumente für Galileo Galilei in Florenz,” in Kunst der Barock in der Toskana, Munich, 1976, pp. 1013–27. See, lastly, also M. Gregori, “Le tombe di Galileo e il palazzo di Vincenzo Viviani,” in La città degli Uffizi, Exhibition catalogue (Florence, 9th October 1982–6th January 1983) Florence: Sansoni, pp. 113–18.

18 Büttner, op. cit., pp. 105–7.

19 Ibid., p. 107.

20 Ibid., p. 110.

21 In MS Galileiano 13 of the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence, at ff. 55r–56r, one reads the “Note of those Signori Florentine Academicians who, as true connoisseurs and grateful admirers of the teaching and incomparable reputation of the famous Signor Galileo Galilei willingly bind themselves to the expense of the sum of 3,000 Scudi, which they intend to use for a noble deposit of marble with statues and following the drawing of.…”

22 The June 30 letter is found in MS Galileiano 164, f. 334r.

23 See the minute autograph of the letter from Viviani to Paolo Falconieri, dated July 10, 1674 (MS Galileiano 159, ff. 34r–36v).

24 Favaro, Amici e Corrispondenti XXIX cit., pp. 1127–9.

25 Such a design was clearly expressed in the letter to Falconieri of July 10, 1674 cited above.

26 The drafts of the epigraphs are titled “Galilaeo ac Sophiae.” Cf. MS Galileiano 318, ff. 328r and 811r.

27 Ibid., f. 811v.

28 The letter was sent only after having received from Baldigiani, who had been previously informed of the confidential nature of the communication, the indication of a “safe” address to which it should be sent.

29 Büttner, op. cit., p. 113.

30 We deduce this from a letter from Lorenzo Bellini to Viviani, dated 8th February, 1693 (probably from Pisa), in MS Galileiano 257, f. 120r: “I am told Signor Foggini is working on, and wants to do the designs of the scrolls, but he needs the inscriptions. I send them to You Sir that you may correct them all, and that you may let me know if you are pleased that they are arranged as indicated.”

31 V. Viviani, De locis solidis secunda divinatio geometrica in quinque libros iniutia temporum amissos Aristaei Senioris Geometrae, Florentiae, Typis Regiae Celsitudinis Apud Petrum Antonium Brigonci, 1701. The inscriptions are published on pp. 120–8 together with engravings of the view of the facade and principal architectural details, the work of Fra Antonio Lorenzini Minore Conventuale. Clemente Nelli (op. cit., I, p. 855) accused Lorenzini of having depicted the facade in an imprecise manner. A. Favaro (“Inedita Galilaeiana. Frammenti tratti dalla Biblioteca Nazionale di Firenze,” in Atti e Memorie dell'Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, XXI, 1880, pp. 35–43) shows the edition of the engraving of the Palazzo dei Cartelloni opposite the text of De locis solidis. They do not differ in important respects.

32 EN, V, p. 39.

33 Pinacotheca imaginum illustrium virorum qui auctore superstite diem suum obierunt. Coloniae Agrippinae, 1643.

34 Favaro, Inedita Galilaeiana cit., p. 42.

35 See note 6 above.

36 MS Galileiano 318, ff. 328r and 811r.

37 Cf. EN, XIX, p. 624: “and thus, no less than in life, honoring after death the immortal fame of the second Florentine Amerigo, not just discoverer of a little land, but of innumerable worlds and new heavenly lights.”

38 Ibid., p. 599. It is worth remembering that Galileo's correct date of birth is February 15.

39 MS Galileiano 11, f. 168v (requests for information from Viviani to Baldinucci, and his reply).

40 Ibid., f. 171r (letter from Filippo Buonarroti of June 7, 1692 to Baldinucci, who had forwarded Viviani's request to him). At f. 168r one reads, moreover, the autograph extract of Viviani of the passage from the expanded edition of Vasari's Vita of Buonarroti where the date and time of the artist's death are specified.

41 Recent attention has been drawn to the falsification of Galileo's date of birth to make it coincide with that of Michelangelo's death, by M. Segre (In the Wake of Galileo, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Univ. Press, 1991, pp. 106–26). According to Segre, Viviani developed the paragone because he intended to propose Galileo as a hero in his Vita, following the model adopted by Vasari for the Vita of Buonarroti. The coincidence between one's date of death and the other's birth would have made more obvious the heroic character of the Pisan's life. Nevertheless, it seems to have escaped Segre that the operation of falsification does not arise with the drafting of the Vita of Galileo (1654) but is verified a good forty years later, at the start of the 1690s. Furthermore, Segre attributes the emphasis of the paragone on the part of Viviani simply to his wish to adhere to a Renaissance biographic cliché, and he avoids questioning himself on the intellectual suggestions of the paragone between the Pisan and the Caprese artist established since Galileo's death.

42 On the myth of Michelangelo, see Romeo De Maio, Michelangelo e la Controriforma, Rome-Bari: Laterza, 1978, especially pp. 447 ff. (but the entire volume is well worth consulting for the many interesting transfigurations of the image of Buonarroti after his death). For the comparison of the two editions of the Vita of Michelangelo by Vasari, with the development, in the second, of the Medicean myth of Buonarroti, see G. Vasari, La Vita di Michelangelo nelle Redazioni del 1550 e del 1568, edited with notes by Paola Barocchi, Milan-Naples: R. Ricciardi, 1962. On the political and celebratory meaning of Michelangelo's funeral, see R. and M. Wittkower, The Divine Michelangelo. The Florentine Academy's homage on his death in 1564, London: Phaidon Publishers 1954.

43 Cf. A. Cecchi, “L'estremo omaggio al'Padre e Maestro di tutte le arti.’ Il monumento funebre di Michelangelo,” in Il Pantheon di Santa Croce a Firenze, ed. L. Berti, Florence: Giunti, 1993, pp. 57–82.

44 Cf. De Maio, op. cit., especially pp. 17–107.

45 Ibid., p. 456; cf. also E. N. Girardi, “La poesia di Michelangelo e l'edizione delle Rime del 1623,” in Studi su Michelangelo Scrittore, Florence, 1974, pp. 79–95.

46 De Maio, op. cit., pp. 17–107.

47 I fully endorse the observations of Eugenio Garin on the fascination wrought on Viviani by the “thesis of the continuity of the Renaissance and of the resurrection from Antiquity of the fields of art and scientific enquiry”: “Galileo e la cultura del suo tempo,” in Scienza e Vita Civile nel Rinascimento Italiano, Rome-Bari: Laterza, 1965, pp. 109–10 and notes 1–2, p. 134.

48 Cf. Nelli, op. cit., p. 840.

49 Cf. De Maio, op. cit., p. 3 and note 2 (p. 11).

50 EN XI, p. 361 (letter from Rome, July 14, 1612).

51 See Vincenzo Ferrone, Scienza, Natura, Religione. Mondo Newtoniano e Cultura Italiana nel Primo Settecento, Naples: Jovene, 1982, especially pp. 109–68.

52 Opere di Galileo Galilei, Nuova Edizione coll'aggiunta di vari trattati dell'istesso autore non più dati alle stampe, 3 vols., Florence: G. Gaetano Tartini and Santi Franchi, 1718. On the significance of the edition and its promoters, see Ferrone, op. cit., pp. 131–5.

53 Lezioni Accademiche, Florence: G. Gaetano Tartini and Santi Franchi, 1716. Cf. Ferrone, op. cit., pp. 135–8.

54 Petri Gassendi, Opera Omnia in Sex Tomos Divisa Curante Nicolao Averanio. Florentiae, apud J. Tartini and S. Franchi, 1727. For the famous and impassioned promoters of this enterprise, cf. Ferrone, op. cit., pp. 155–62.

55 The thesis of the close relationship, under Gian Gastone, between civil rebirth and valorization of the Galilean tradition was already marked out by Riguccio Galluzzi in Istoria del Granducato di Toscana sotto il Governo della Casa Medici, 8 vols., Florence, 1781. Such a thesis was proposed again by Niccolo Rodolico (Stato e Chiesa in Toscana durante la Reggenza Lorenese, reprint from the first edition of 1910 with Introduction by Giovanni Spadolini, Florence, 1972). One still lacks exhaustive investigations that would allow the reconstruction of whether, and to what extent, this welding between the exigency of civil renewal and the fertile rebirth of the Galilean lesson was the consequence of an intentional strategy firmly adopted by the Prince.

56 Cf. Nicola Carranza, Monsignor Gaspare Cerati Provveditore dell'Università di Pisa nel Settecento delle Riforme, Pisa: Pacini, 1974.

57 On the diffusion and characterization of Freemasonry in Tuscany, see Carlo Francovich, Storia della Massoneria in Italia. Dalle Origini alla Rivoluzione Francese, Florence: La Nuova Italia 1989, especially pp. 49–85. See also the excellent essay by Fabia Borroni Salvadori, “Tra la fine del Granducato e la Reggenza: Filippo Stosch a Firenze,” Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, serie III, vol. VIII (2) (1978), pp. 565–614.

58 Cf. I documenti del processo di Galileo Galilei, pp. 214–15.

59 Ibid., p. 216.

60 Cf. Umberto Dorini, La Società Colombaria, Accademia di Studi Storici, Letterari, Scientifici e di Belle Arti. Cronistoria dal 1735 al 1935, Florence: Chiari 1935, p. 230.

61 The original Act is at the State Archive of Florence, Notarile Moderno, notary G. Camillo Piombanti, Prot. 25, 439, March 12, 1737. Thanks to Dr. Orsola Gori of the State Archive of Florence, who, at my request, swiftly traced this, providing me also with additional extremely interesting information about other personalities involved in this event.

62 On Cocchi, see the excellent entry of U. Baldini, in the Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Rome, 1960, Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, XXVI (1982), pp. 451–61.

63 On the masonic inclinations of Abbot Niccolini, see Francovich, op. cit., pp. 54 ff. Cf. also Carranza, op. cit., passim.

64 Cf. the classic work of Ferdinando Sbigoli, Tommaso Crudeli e i primi Framassoni in Firenze. Narrazione storica corredata di documenti inediti, Milan, 1884.

65 Ibid., p. 148. For a presumed adoption of the Copernican thesis on the part of the notorious Baron Stosch, see Borroni Salvadori, op. cit., p. 592.

66 Information on Giovanni Camillo di Pasquale di Piero Piombanti and on his functions as a frequently used notary of many Florentine public magistracies and cultural institutions, as well as a number of major families (Ginori, Nelli, Neri, Niccolini, Rucellai, etc.) that played an important civic role in the passage from Medicean dynasty to the Regency, has generously been given to me by Dr. Orsola Gori, to whom I express many thanks. For the familial relationship of Piombanti with Antonio Cocchi, see the entry A. Cocchi by U. Baldini, in the Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, p. 437. Some letters of C. Piombanti are to be found amongst the Cocchi papers (cf. A. M. Megal Valenti, Le Carte di Antonio Cocchi, Milan: Bibliografica 1990). See also M. A. Timpanaro Morelli, Per una Storia di Andrea Bonducci, (Firenze 1715–1766), Rome 1996, pp. 249–254.

67 See the description by Vasari in the second and expanded edition of the Vita di Michelangelo (Giorgio Vasari, Le Vite… nelle redazioni del 1550 e 1558, text edited by R. Bettarini, historical commentary by P. Barocchi, vol. VI, Florence: Spes, 1987, pp. 126–7).

68 The epigraph can be read in G. B. Clemente Nelli, Vita cit., p. 880. On the personality of Peruzzi and the official role he played on the occasion of the solemn funeral rites of Gian Gastone, see Marcello Verga, Da Cittadini a Nobili. Lotta Politica e Riforma delle Istituzioni nella Toscana di Francesco Stefano, Milan: Angeli, 1990, pp. 53–5.

69 Ibid., pp. 876–7.

70 See above, note 61.

71 Cf. A. Favaro, “A proposito del dito indice di Galileo,” Scampoli Galileiani, CXLI, reprint with introduction and indices by Lucia Rossetti and Maria Laura Soppelsa, 2 vols., Padua: Antinore, 1992, II, pp. 679–88. The reconstruction of the exact number and nature of the fragments (or should one say, relics) taken from Galileo's remains, as well as their fates, gave origin to an erudite, colorful, and bitter historiographical-documentary dispute, in which there competed, among others, Giuseppe Palagi (Del Dito Indice della Mano Destra di Galileo. Memoria, Florence: Le Monnier's heirs, 1874) and, later, his severest critic Pietro Gori Le Preziossime Reliquie di Galileo Galilei. Reintegrazione Storica, Florence: Tipografia Galletti e Cocci, 1990.

72 Cf. Museo di Storia della Scienza, Catalogo, ed. M. Miniati, Florence: Giunti, 1991, p. 62. Before being displayed in its current location, the famous finger suffered noteworthy vicissitudes, to the point of being considered lost. It was finally rediscovered in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, whence, in March 1804, it was moved to the Museo di Fisica. The delivery was marked by a solemn and long speech, which is today conserved in the Archive of the Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza di Firenze (MS 189).

73 See the Processo verbale pel collocamento di una vertebra di Galileo Galilei nella Sala di Fisica dell'I. R. Università di Padova, Padua: Tipografia Crescini, 1823.

74 G. Targioni Tozzetti, Notizie degli Aggrandimenti delle Scienze Fisiche Accaduti in Toscana nel Corso di Anni LX del Secolo XVII, 3. vols., Florence: Giuseppe Bouchard, 1780, 1, p. 142.

75 Nelli, op. cit, pp. 878–80.

76 Cirri, in the Sepoltuario (Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence, Manuscripts Room), immediately after having reported the hypothesis that the woman in the coffin was Alessandra Bandini, puts forward this suggestive hypothesis: “Oh, why could it not be the remains of Sister Maria Celeste, daughter of Galileo, whose tomb at Arcetri in the Church of S. Matteo has been sought in vain?” (f. 992). But then he adds in parentheses “(it cannot be)” without, nevertheless, indicating the motives that led him to this conclusion.

* Translated by Michael John Gorman.