CHAPTER SEVEN

Supersized councils

– Disempowered Communities

IT WAS 1.30am on 11 July 2006 – a time and date arrived at by precise calculation. My archaeo-astronomer friend Dougie Scott had assured me this was the best time to view the lunar standstill which ‘activates’ the Standing Stones of Callanish on the Hebridean island of Lewis. This part of the moon’s cycle happens once every 18.6 years. And tonight was the night.

So I was hurtling in a transit from Atlantic-facing Uig on the remote west coast towards 5,000-year-old stone circle. The van was driven by Maxwell MacLeod, my friend and support driver who’d been accompanying me while I (mostly) cycled up the Western Isles recording a 13-part series about Hebridean life for BBC Radio Scotland.

What has any of this got to do with localism? Bear with me.

Dougie believes Scotland’s key stone circles are set out like calendars to mark the lowest and highest orbits of the sun and the moon. He thinks our forebears believed the sun and moon ‘impregnated’ Mother Earth with energy, bringing forth crops and new life. And he’s spent enough early mornings measuring celestial alignments in remote sites to prove it. His theory seems fair enough to me, but has apparently caused irritation among ‘proper’ scientists, who say no such inferences can be drawn, even though so many sites are oriented precisely to key positions of the sun and moon thousands of years ago.

Anyway, Callanish is the Mother of all lunar sites, and 1.30am on 11 July 2006 was the precise moment Dougie’s theory would be put to the test. Then the moon would emerge from behind the mountain known as the Cailleach na Mointeach (Old Woman of the Moors) and ‘walk’ along her undulating shape before sending shafts of moonlight down the stone flanked avenue at Callanish, briefly illuminating her two tall, central stones. Fairly reproductive sounding, if you ask me.

Anyway, 18.6 years earlier, when the lunar standstill last occurred, folk came from all over the world to witness the ‘Moon walking at Callanish’, including a group of Japanese tourists who had hired a jet and travelled to each archaeological treasure with lunar orientation around the world, collecting small bags of earth which they carefully deposited at the next site in the kind of makey-uppey, yet purposeful, ritual I wish I’d thought of (and could finance) myself. Every self- respecting hippie, New Age traveller and Waterboys fan for miles around was expected to be there – in short, the pagan nature of this celestial event promised an entertaining evening – as long as we had all calculated the same kick-off time.

Even if Dougie Scott had the right time, we might see the moon but not the masses if calculations differed. And it was people I had come to record. We hummed and hawed. ‘Let’s just go,’ said Max at midnight.

So we did – and headed for Callanish with clouds building and excitement growing. At the car park, there were only seven cars. Hardly evidence of a lunar stampede. Fearing the worst, I wandered up the path. Suddenly ethereal chanting filled the air. Sure enough, silhouetted against an iridescent sky was the shape of druid-type gowns. Seconds later, the steady beat of drums and scent of incense were unmistakable.

I already had the tape recorder running, in case our own remarks were the only sounds I managed to record – just as well. Out of the darkness, we bumped into a bearded Jethro Tull lookalike carrying a set of bagpipes. We asked if the big moon moment had already happened. He wasn’t sure.

‘Something happened half an hour ago and all the pagans started howling – you know that ululating thing they do. Then this Free Church choir started singing in Gaelic, and for a crazy moment they seemed to be trying to outdo one another. I mean it’s nothing to me, eh. I’m fae Fife. But I thought, this is crap. If this moon thing means something, then don’t fight over it – just let it happen. But they were all still singing at each other, so I thought the pipes will sort this out and started playing ‘Amazing Grace’ over the lot of them. It was so loud it drowned them all out – so they gave up and started to sing along. Magic.’

‘So that’s you away home now?’

‘Aye, that’s enough. I’ve been here for the past two nights as well. Time to get back to Cumbernauld.’

‘I thought you said you were from Fife?’

‘I am – my God, I’m not from Cumbernauld. I just have to stay there. But I’m in it, not of it. Know what I mean? In it, not of it.’

Bizarre as that night proved to be – culminating in a stand-off between a 70-year-old shamanic astrologer from Louisiana and a local Free Church ensemble – it was the piper’s description of his erstwhile home that stayed with me longest.

In it, not of it.

How could the Pied Piper of Callanish have such a thoroughly disconnected life back ‘home’? Admittedly the dated-looking collection of roundabouts and dual carriageways that’s earned the New Town ‘Plook on the Plinth’ status is not easy to love. And who knows what personal sorrows may be associated in the piper’s memory with that single word, Cumbernauld?

Still. In it, not of it. Like a man inhabiting a prison cell. The phrase stayed with me, because it summed up a remoteness and apparent contempt towards place that’s common in Scotland and yet entirely at odds with the kind of people using it.

The bearded bagpiper was no slouch. He’d learned to play an instrument, chosen to travel hundreds of miles to an empty moor, intervened with a spot of bagpipe diplomacy when unseemly quarrels erupted and finally exercised the common sense to leave once the clouds (and midges) descended. This Fifer was clearly an outgoing, active and capable man who might be expected to respond positively to everything around him. Not Pollyanna perhaps, but no shrinking violet either.

And yet he actively disliked the place he lived and wanted everyone to know it.

In it, not of it. Such a lack of belonging is commonplace in Scotland. Is that because we don’t value place or because we lack control over the community, land, buildings, society and nature that must come together to create it? I suspect it’s the latter.

Take the classic west of Scotland greeting – ‘Where do you stay?’

Not where do you live – but where do you stay? The dictionary tells us that ‘to stay‘ means to be fixed, immobile, inert, immovable, motionless, riveted, sedentary, stationary, transfixed. None of these words convey a cheery, active or positive life experience. So what does it mean when Scots describe where they stay? Is it a slip of the tongue, a meaningless way of speaking, a small semantic point one shouldn’t exaggerate? Or a bit of a giveaway? Well-trained dogs stay. Inanimate objects stay. Rabbits in hutches stay. Books on library shelves stay. But people in places ‘live’ – don’t they?

People put down roots, explore surroundings, customise their environment, get to know neighbours, attend school, go to the doctor, hang around street corners, acquire accents, catch the bus, miss the bus, get bored, visit friends, collect prescriptions, use the post office and grunt hello to people in the street. All of this happens locally.

That’s why place matters. Education, housing, language, friendship and play first happen on the doorstep, not further afield. Early ideas of fairness, fun, danger and acceptable behaviour are also developed under our noses. To paraphrase John Lennon, life’s also what happens where you’re busy making other plans.

When we are young, life is completely local. Adventure is the little wall you finally have the courage to walk along alone. Nature is the small patch of dandelions halfway home from school. Posh is the tennis club where people play with their own rackets. Huge is the Goliath crane. And loud is the sound that wakes you from sleep in the middle of the night. OK – my early ideas were deeply coloured by growing up in Belfast. But that’s the point. That’s the power of locality. It creates a sense of normality – even in abnormal situations – through deep, subconscious attachment.

People are increasingly understanding the power of early years in shaping children and their lifelong outlooks and capacities. By the age of three, children have acquired (or failed to acquire) half their adult vocabulary, learned teamwork, acquired negotiating skills and bonded strongly with the people and ways of life around them. They do that – or fail to do that – in particular places. If Jesuits believed they owned a young life by directing it until the age of seven, how much more powerful is the place that forms us until our late teenage years?

And yet ‘normal’ life in Scottish places disempowers local communities and denies citizens an effective and organised way to pour energy into that most important place – their own backyard.

Why? Because Scots have the biggest councils with the lowest levels of local democratic activity, the biggest and most remote landowners and the weakest community councils in Europe.

In it, not of it Scotland – we all live there.

The land we see, the streets we walk on, the rivers we walk beside, the problems we witness – they’re all there for someone else to fix, somewhere else to tackle. It’s why we pay our council tax, isn’t it? For someone else to bag problems and take them away? Except they can’t.

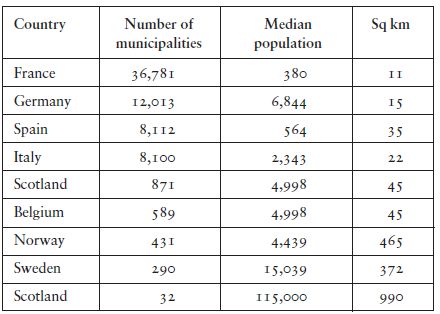

The average population of a Scottish council is a whopping 163,000 people (the median is 115,000 people – see Figure 13). Most of our European neighbours have county councils this size. But they also have a smaller, more loved, more vigorously contested and more vibrant ‘delivery tier’ of community-sized local councils as well. Scotland, along with the rest of the UK, doesn’t. Our 32 enormous councils try to do everything – the strategic co-ordination work of a county council and the truly local delivery work of a parish council. It’s an impossible task and it’s the community level that suffers. Genuinely local simply doesn’t exist in Scotland – except where hard-pressed, determined, unfunded, voluntary groups have decided to act and pump life back into their communities. I sense raised eyebrows.

Local council size across Europe1

How does this picture square with the Scotland of a hundred Highland Games, several dozen Feisean (Gaelic learning festivals), night schools, sports clubs and folk nights? Surely Scotland is full of particular places – distinct, fiercely defended by their inhabitants and loved. That’s all true. But it’s true despite the official structures – not because of them. Even the keenest volunteers who make life vibrant and interesting don’t run the places they light up – ‘local’ units of governance are too large and election is too dominated by political parties. Towns, villages, islands and communities are all run by council hqs in larger settlements elsewhere.

And it’s been like that for a while.

The democratic heart of ‘small town’ Scotland was ripped out in 1996, when 32 unitary authorities replaced 65 old style councils – nine regions, 53 districts and three island councils. Mind you, the big local downsizing had already occurred. In 1975, a mixter-maxter of more than 400 counties, counties of cities, large burghs and small burghs was swept away and before that in 1930, 871 parish councils were axed as democratic structures (though they still exist for census purposes).

That’s quite a change. In my own village in Fife, for example, rents paid in the village for council housing were once used to employ ‘the drain man’ who went round unblocking drains, gutters, roans and pipes. Now we are part of Fife council, with headquarters 40 minutes distant, there is no local ‘drain man’ and flooding is so common, flood alert road signs are stashed all the way along main routes into Perth – ‘for convenience’. Meaningful village control largely disappeared in the 1930s. Meaningful town control went in 1975. And after 1996 many places became non-existent – in the eyes of the authorities at least.

The 1996 reforms probably saved some money. Undoubtedly the smaller system looked more efficient on paper. But it also severed the vital link between people and place in Scotland.

So this is where the ‘best wee country in the world’ is currently run – somewhere else.

In Norway, Finland, Denmark, France, Germany, Holland and Belgium, towns like St Andrews, Saltcoats, Kirkcaldy, Fort William, Kelso, Pitlochry or Methil and islands like Barra, North Uist, Westray and Unst would have their own councils because our neighbours fought to remain localised.

But in Scotland today, big is efficient and efficient is beautiful. So Scots inhabit the least locally empowered country (perhaps) in the developed world and tend to look higher (to national policy) or lower (to micromanaged families) for solving problems – even when the answer is genuine local control. Its absence is Scotland’s enduring blind spot.

Take three towns; Wick, Fort William and Linlithgow.

Wick used to be one of the largest herring ports in Europe, the county town of Caithness (sorry, Thurso) and a royal burgh. Now it’s run from council headquarters a three hour rail journey away in Inverness. Meanwhile, 1,200 miles further north sits Hammerfest – the world’s northernmost town and the county town of Finnmark. In 1900, Wick and Hammerfest were both busy North Sea ports. Today both have around 9,000 inhabitants – but one is thriving and one is struggling.

Hammerfest was the first place in Northern Europe to have street lighting powered by river hydros and funded by a local tax on beer in 1897. Townspeople went on to experiment with that turbine technology in the fast running straits at nearby Kvalsund. Years of relatively hassle-free access to their own waters helped the local energy company Hammerfest Strom become experts in tidal turbine technology and now the company is providing the kit for Scottish Power to make Islay the world’s first tidal-powered island in 2015. The Hammerfest firm now called Andritz Hydro Hammerfest – has also won the tender to exploit the mother of all tidal stream sites off Duncansby Head in the Pentland Firth – 16 miles north of declining Wick, which lost its official port status a decade back.

It’s the ultimate irony. Wick’s inhabitants (including my own family) survived centuries of pummelling by the North Sea aboard fishing boats, lifeboats, oil supply boats and pilot ships. But Wickers didn’t have easy access, local control, cash, investment or sufficient local belief to turn their intimate knowledge of a cruel sea into energy harnessing technology.

Today the ports look very different – one is constantly busy, the other is very quiet. One has been raising its own taxes and deciding how to spend them for centuries. One hasn’t.

I’ll grant you, other factors are also at play.

But the Wickers’ frustration at being forced to tackle decline with both hands tied behind their backs is palpable. And Wick is not alone.

Wick 1900s, from the Johnston Collection.2

Hammerfest, 1900s.

Wick and Hammerfest 2012 (Hammerfest courtesy of Johan Wilhagen – Visitnorway.com).

A few years back, I was asked to speak at a Rotary event in Fort William. As the crowd gathered in the reception area, conversation was downbeat. High rates bills meant shops were closing and boarded up windows, Poundstretcher chain stores and a legion of charity shops had begun to dominate the High Street. The ring road, built decades earlier, meant most people bypassed the town. The crumbling 1960s facades of many buildings needed repair and, despite the innovation of the Mountain Film Festival, mountain biking, the ski lift at nearby Aonach Mor and the enduring natural spectacle of Ben Nevis, Fort William itself seemed shabby – a disappointment at the end of the West Highland Way.

Once spoken about, it was a situation that plunged the entire banqueting suite of retired town planners, retailers, secretaries, shop owners, lorry drivers, council officials and civil engineers into almost unshakeable gloom. So I ditched my speech. Asking for a show of hands to demonstrate the level and range of expertise sitting in that function room alone, I suggested they had more than enough experience, commitment and affection to resurrect Fort William themselves. The mood lifted. There was a momentary buzz. Folk looked around like chefs planning a complicated, ambitious menu. Yes – all the raw ingredients are to hand. Yes, we could easily work together and put the time in. We could fix everything here. We could raise money, hold ceilidhs, get the young folk involved and… then something visibly knocked the wind from their collective sails. It’s not our place to do this. We aren’t councillors. It’s too hard to get involved. Anything we do will be against some rule. And there’s no love lost for well-meaning amateurs. The moment passed.

So it is in communities across Scotland. Local places are run by Europe’s smallest councillor cohort who make decisions about villages, towns and cities they hardly know and can rarely visit. And while they vainly try to micromanage distant lives, local people are freed from the burden and responsibility of fixing what’s around them but also robbed of the powerful feelings of rootedness and attachment that come from improving places, not just ‘staying’ in them.

There is only one thing at which any place excels – being itself. And there is only one set of people who fully understand that – the people who live there. Right now, capable people all across Scotland can only stand and survey the failing public façades of their local lives.

At a meeting set up to counter decline in historic Linlithgow, I was again urging self-help. A businessman told me local efforts had got nowhere – symbolised by a non-functioning light bulb in a nearby underpass.

‘The council say they fix it, but every time I walk home, the light’s not working. Maybe it’s kids. Maybe they don’t even change the bulb. When I complain, they say it costs too much to send a workman out. So what happens? Nothing! Why do I pay council tax if the council can’t even keep an underpass lit?’

‘So why don’t you change the bulb yourself?’

‘What!’

‘Change it yourself if it annoys you so much.’

‘It’s not my job – why should I?’

‘Listen to yourself. You are consumed with anger over a £1 light bulb. Change it, act, do something, take charge.’

There was laughter, a release of tension and then a resigned shake of the head.

‘I can’t. They’ll prosecute me for interfering with council property.’ Mr Light Bulb was probably right. This is the simmering rage and wasted energy that lies at the heart of almost every local community. Little things cannot be fixed by capable local people. New ideas cannot be tried out. The people elected and employed to make decisions about the most important and intimate aspects of life are generally strangers.

There could be few more vivid depictions of the infantilisation caused by disempowering and distant ‘local’ governance than grown men infuriated by broken light bulbs they feel unable to change. Where does that frustration and fury go? Think of Einstein’s famous maxim: ‘Energy cannot be created or destroyed, it can only be changed from one form to another.’

So what happens to the desire to fix when it cannot find an outlet? Where does that energy go? Thwarted goodwill is eventually transformed into cynicism and civic detachment – amongst some folk it may even manifest as vandalising rage. Disempowerment is a volatile state.

So welcome to Scotland – a country full of local places where most inhabitants are marking time. A place randomly chosen to suit convenience, habit, or proximity to work. Places which do not want your input – just your council tax. Places Scots must thole.

‘I’m not from Cumbernauld – I just stay there.’ Those words conjure up all the weary passivity and stultifying boredom that characterises life in small-town Scotland. The conclusion is inescapable.

The ‘best wee country in the world’ is run in units that are far too big.

The mountain village of Crianlarich, for example, is overlooked by Munros from whose summits you can look west to the Atlantic. Yet it is run by Stirling Council, whose headquarters almost lap the North Sea on Scotland’s east coast. The tiny Hebridean island of Barra is run by councillors six islands distant. Massive Easterhouse – which could be the 19th largest town in Scotland by population size – is just another part of Glasgow Council.

In a way, this human-scale-defying ‘bigness’ mirrors the vast size and remote management of many Scottish landholdings. Some lairds and pinstriped gents from the Crown Estates Commission run the land and coastal waters from miles even continents away. Is it really any surprise that our towns, villages, islands, housing estates, suburbs and cities are also run at a distance? The political and social consequences of distant democracy are profound. According to the latest Scottish Household Survey, only 22 per cent of Scots think they can have any impact on the way their local area functions. That’s a terrible condemnation of Scottish democracy. Local should be the most important dimension in our lives. And yet almost four-fifths of Scots think their neck of the woods is run by other people – not folk like themselves. And they’re absolutely right. Let’s return to Fife. Between 1894 and 1930, the Kingdom had 82 parish councils. Until 1975, it had 33. Now it has just one. I’m grateful to Andy Wightman, land reformer campaigner and erstwhile co-performer in our Edinburgh Festival Fringe show the Scottish Six, for ‘doing the maths’ (Figure 15). He showed that if Scotland returned to its old pre-1930 parish council structure it would sit mid-way in the European league table of local democracy between the Norwegians and Germans – not a bad place to be.

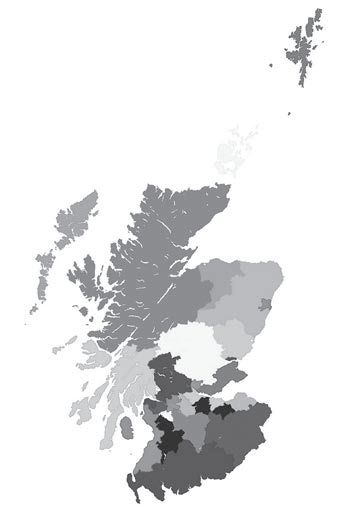

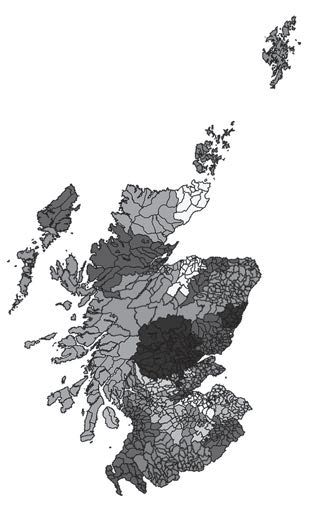

Putting it the other way round, becoming ‘normally local’ in a European context would change Scotland’s council map back from the current reality (left) to pre-1930 boundaries (right, in Figure 16 below). This is how atypical Scotland has become. But preoccupied with almost equally oversized England and cut off from our ultra-local European neighbours – we have failed to notice.

Our super-sized democracy is completely out of kilter with the rest of Europe. Admittedly, the French are almost crazily local – their smallest commune has just 89 people. But the average unit of local government in Europe is closer to the population size served in Scotland by toothless community councils. Deliberately shorn of power, each community council has an average budget of just £400 a year. A recent attempt to raise interest by limiting the number of seats – thereby triggering elections – didn’t happen because the legislation wasn’t authorised by higher tiers of governance. So it’s true. Community councils are full of virtually self-nominated people with time on their hands. Given deliberate efforts to make them that way, it’s a miracle any function properly at all.

Figure 15: European Municipal Government with Scottish parish councils restored.

Figure 16: Scottish Councils 2012 (left) and 1929 (right).

No matter what any Scottish politician says about the importance of community, no matter how much anyone praises ‘vital voluntary effort’, no matter how many fetes, roups, fairs, Highland games and car boot sales are opened by hand-pumping councillors, MSPs and MPs, no matter how many ‘planning for real’ ‘consultation exercises’ are conducted with ‘the grassroots’ – remember that £400. That’s how much structural community democracy in Scotland really matters.

But is anyone really bothered? Well, I suppose we don’t miss what we’ve never had – truly local democracy and effective community delivery.

If a 38 per cent turnout at the 2012 Scottish local government election is not a mandate to transform local government – then what is?

Strangely, even Tories (almost) agree. The Tory MEP Daniel Hannan made this case for localism:

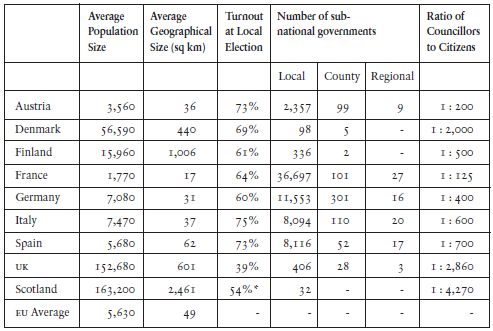

‘Give councils more power and you will attract a higher calibre of candidate as well as boosting participation at local elections. In Britain, local authorities raise 25 per cent of their budgets and turnout is typically around 30 per cent. In France, those figures are, respectively, 50 and 55 per cent; in Switzerland 85 and 90 per cent.’ It’s an interesting comparison – and not just because French councils raise more cash and enjoy higher voter turnout. They also have the tiniest units of local governance – 36,000 communes with an average population of just 380 – compared to Scotland’s 32 councils with an average population of 165,000. Likewise the Swiss, Austrians, Finns and Germans (see figure 17). Norway – with the same population as Scotland – has local election turnouts of more than 70 per cent amongst 431 municipalities which run primary and secondary education, outpatient health, senior citizen and social services, unemployment, planning, economic development, and roads. Scottish council elections in 2011 had a 38 per cent turnout amongst 32 councils. Coincidence? Local government across Europe means decision-making by people like your mum, neighbour or other ‘weel kent’ faces. In Scotland, it means control by people you don’t know. Could that be why Scots don’t vote?

Figure 17: International comparison of council size and voter turnout.3

The recent Silent Crisis report by the Jimmy Reid Foundation (summary above) demonstrates Scotland’s unhealthy place in the democratic league table of Europe. Feast your eyes and think it through a bit. In Austria, the ratio of councillors to citizens is one councillor per 200 people. In Scotland, it’s one councillor per 4,270 people.

Put it another way. In Norway, one in 81 people stands for election in their community. In Scotland, it’s one in 2,071.

Or look at it this way: in Sweden, 4.4 people contest each seat. In Scotland, it’s 2.1.

Using every indicator available to identify the health of local democracy, Scotland performs worse than any other comparable northern nation. That’s what led the report’s authors to conclude that ‘Scotland is the least democratic country in the European Union’.

North or South, Baltic or Mediterranean – most European states are micro-sized at their local tier, which means more grassroots connection, traction, trust, effective service delivery and involvement than Scots can ever hope to generate. Instead decisions and services are shipped in from remote authorities elsewhere.

What does that mean in practice?

In the most powerfully municipal Nordic nations, levels of ‘social trust’ amongst citizens and between citizens and government are the highest in the world.4 That has tangible benefits. According to the Economist:

High levels of trust result in lower transaction costs – there is no need to resort to American-style lawsuits or Italian-style quid-pro-quo deals in order to get things done. But its virtues go beyond that. Trust means that high-quality people join the civil service. Citizens pay their taxes and play by the rules. Government decisions are widely accepted.5

Perhaps that’s because more Norwegians ARE the government and know they are trusted by neighbours to manage spending and life decisions locally. As Britain’s many crises of trust demonstrate, you can’t put a price on democratically regulated, high levels of mutual confidence.

What happens when proximity and involvement in political decisions are missing from communities?

A 2013 report by the Federation of Small Business and the Centre for Local Economic Strategies revealed Scottish councils spend less of their budget with local firms (27 per cent) than the UK average (31 per cent).6 And UK such local spending is already at the lowest levels in Northern Europe.

In their defence, councils insist that rules about ‘best value’ and European procurement procedures stop them preferring local suppliers. Strange that other EU members seem to manage. Perhaps the truth is that Scottish council chiefs are far closer to their own staff (especially legal officers) in the ivory towers of large remote council offices than council chiefs in nations with much smaller units of local government. Perhaps being physically close, accessible, responsive and responsible to a small number of people makes it harder to prioritise legal compliance over local livelihoods.

The vast majority of Nordic MPs started life in dynamic municipal government so they plan with an expectation of local capacity and factor that dimension into every policy. The opposite is true in Britain. Politicians of all parties like the sound of involving local people but in practice, most MSPs and MPs wouldn’t trust communities to run the proverbial in a brewery. They ‘know’ because they’ve been there. And so the vicious circle continues. Local remains an unimportant backwater in the eyes of national politicians instead of a powerhouse for social and economic change.

So we are stuck with the biggest ‘local’ government in Europe – too large to really connect with people and yet too small to achieve maximum efficiencies of scale. Kind of the mummy-sized bowl in Goldilocks and the Three Bears – betwixt and between and going nowhere fast. The logic of the current direction is inescapable. Why do we need any local councils at all?

None of this is meant to criticise councillors. Structures are to blame, not individuals. Most councillors make a huge effort to be all things to all people, tackling strategy at council HQ and trying to engage with community activists too. Some councillors are obstacles to community growth, and behave defensively if anyone tries to ‘interfere’ – but I’m sure that happens the world over.

Highland Council covers an area the size of Belgium, with a population the size of Belfast. Councillors regularly drive hundreds of thousands of miles a year to create a sense of connection through meetings, surgeries and local events. Despite such superhuman efforts, many remote communities still feel excluded – reduced to questioning, suspecting and vetoing whatever emanates from the centre. Meanwhile, Europe’s fastest growing city also lacks a dedicated council of its own – although a pilot resurrection of old area committees by the newly elected Highland Council may help.

Those who run Scotland’s overlarge authorities are on big salaries and a losing wicket. Many struggle valiantly to keep their ears to the ground. But the ground is simply too large. Ironically, this just means more money spent on consultation, resulting in a low response rate and yet further erosion of councillor confidence in community capacity. So what will change?

If self-determination is good enough for Scotland, it’s good enough for Scotland’s communities too. If power and responsibility can renew Scotland, then a democratic stimulus can also give a leg up to capable, active communities. Instead they are being micro-managed badly from on high while politicians bemoan punter apathy. Wrong-sized layers of governance allow power to be hoovered upwards by the nearest quango or distant council not devolved downwards to the nearest competent community unit. Scotland needs smaller, more meaningful, democratically accountable units of organisation before big policy gains will follow.

In the absence of truly local councils, development trusts have become the most effective vehicles for communities that want control of their own destinies. There’s a legal question mark over community councils owning assets. So development trusts have been set up to own and manage orchards, housing, land buyouts, lochs, pubs, libraries, bridges, libraries, community centres, wind turbines, shops, transport and even a hospital – and in the process a very practical, capable and focused set of people has been gathered together.

Some of the poorest Glaswegians worked together to restore Govanhill Baths – a decade-long campaign to retain a swimming pool against the wishes of Glasgow Council. The project has produced much more than a beautiful set of Victorian Baths – the people of Govanhill are now purposefully organised in their own development trust and are taking on responsibility for their own health and wellbeing. The more services that can be channelled through this popular, community-driven vehicle, the better.

And yet the vast bulk of social and welfare spending in Govanhill and elsewhere is channelled through local offices of large councils whose paid staff often live elsewhere. The present council setup delivers a clear message to local, active, capable Scots. Your job is to stand still while we fix you. Happily most folk in development trusts aren’t listening.

West Kilbride in Ayrshire is another sparkling example of successful, community-driven regeneration where conventional ‘top down’ policy had drawn a blank. This 19th century former weaving town suffered from high unemployment and competition from out-of-town shopping centres. At one point, half the local shops were boarded up. In 1998, the West Kilbride Community Initiative (WKCI) was set up by locals with one craft shop opening on the High Street. Other skilled craftspeople took over derelict shops and profits were ploughed back into the town. In 2006, West Kilbride won the Enterprising Britain competition. Now eight artists’ studios, an exhibition gallery, a delicatessen, a photography business, a clock and watch repairer, a bridal shop and a graphic design business have opened and the existing butcher, baker and greengrocer have been able to stay put. In 2001, the Trust bought the old Barony Church in the heart of the town, which was in desperate need of repair. I was an Any Questions panellist there in 2012 on the opening night of the London Olympics. We wondered why such a lively crowd had turned out despite competition from the biggest TV experience of the decade. We didn’t realise we were sitting inside a labour of love. Further along West Kilbride’s main street, an outdoor theatre’s being developed on the site of an old Corn Mill and a scheme’s under way in a disused quarry to recycle the village’s domestic organic waste through composting and vermi-composting (worms) financed through a Landfill Tax credit scheme. These guys may be good at compost – they’re better at filling out forms and applying for grants and awards. And even better at drumming up trade and selling local goods and services to fellow locals.

None of this is formal council activity. If local people had not decided to take action in a voluntary development trust, West Kilbride might today be dead as a dodo – or as lifeless as many other neighbouring towns without the same level of community control. Elsewhere wind farms owned by Development Trusts will soon be netting millions, whilst ‘normal‘ communities receive peanuts, and payments are often siphoned off by landowners and councils. Already in Fintry near Glasgow, community wind cash has paid to insulate homes and replace axed bus services. It’s a silent revolution. There isn’t a more optimistic, can-do, practical bunch of people anywhere in Scotland. And yet hardly any are elected councillors. There’s too much to do closer to home.

Capable, connected, powerful communities – based on the kind of dynamism demonstrated by development trusts – could generate energy, supply district heating, find work for unemployed young people, tackle local flooding problems, fix derelict buildings, build and manage housing and keep an eye on old folk, helping them stay out of hospital and the personal care budget stay under control.

This kind of social transformation is already happening via the development trust that runs the island of Eigg – and the West Whitlawburn housing co-operative.

There’s a lesson and a challenge here for the Scottish Government. As councils face the task of saving millions from budgets, hundreds of land and wind-energy rich community development trusts are deciding how to spend their dividends. Should they treat the cash as ‘extra money’ – providing window boxes, traffic calming or other marginal improvements when roads are pot-holed, energy costs are through the roof, old folk need carers and young parents need affordable child-care? Or, if they spend money on core council services, will they prompt local authorities to pull-out altogether and end up as DIY communities where residents pay council tax for next-to-nothing? The solution might be to transfer some council tax income to self-governing communities. I can hear the howls of protest already. But what’s the alternative? Do we just pat successful communities on the head and continue to fund municipal failure?

There are around 200 development trusts in Scotland – community led, multiple activity, enterprising, partnership oriented and keen to move away from reliance on grants. Could they help run Scotland?

Actually, they already are. Cost-cutting councils are already closing libraries and village halls. The SNP government does not appear to smile upon our over-large councils. Nor does it want community-sized councils to take over. Development Trusts may seem to be an ideal intermediate solution.But can this ad hoc situation work in the long term when all involved are un-elected volunteers and councils still expect council tax bills to be paid regardless of local service provision?

The difference in democratic vitality across the North Sea has to be seen to be believed.

Five summers ago I visited the small town of Seyðisfjörður in north-east Iceland (population 668) and was impressed to see gangs of youngsters mending fences, mowing grass, and painting walls at the local hospital. ‘Yes, the municipality decided to pay them a small amount to fix the town every summer. The older kids guide the young ones, they don’t get bored, they learn to earn money, work as a team and we get everything ready for the tourist season.’ It made so much sense.

‘Doesn’t the hospital have to employ unionised labour for work like that?’

‘Well, along with two neighbouring municipalities, we run the hospital too.’

Gobsmacked was too small a word.

Three years ago, in snow so deep it would have brought Scotland grinding to a halt, I visited the Medas Outdoor Kindergarten in Arctic Norway.

The national Norwegian government had called for farmers to diversify and for children to have at least one full day outside per week. So the local municipality backed a bright idea by local farmers Jostein and Anita Hunstad – a farm kindergarten where the children feed and care for the animals, make hay, grow vegetables and sell eggs and tomatoes in local villages at the weekends to raise funds for school trips. There are now 100 similar farm kindergartens across northern Norway. Did health and safety people from Oslo have concerns?

‘No, I think we are all happy here. Why would outside agencies get involved?’

Why indeed?

Some winters ago, on the Swedish island of Gotland (pop 57,000), I met Development Director Bertil Klintbom, who invited me to the opening of a new pier. For centuries, Gotland was a vital stepping stone in Baltic trade until the Cold War ended ferry travel and the port status of Slite.

So the municipality struck on an ambitious and controversial plan. In 2008 they gave the Russian government permission to lay a new trans-continental gas pipeline within Gotland’s territorial waters in exchange for the use of Slite as the Russian’s Baltic pipe-laying base, an (upfront) payment for its refurbishment and a contribution to the cost of a new hydrogen-powered trans-Baltic ferry.

Did the Swedish government have a say?

‘Why should they?’

In Sweden, only those earning above £30,000 per annum pay any tax to central government. Income tax is paid to relatively tiny municipalities which in turn deliver most of the services used by citizens. Only corporation tax and higher earner income tax goes straight to the centre. Describe the Scottish system, where all taxes are sucked into Westminster and grudgingly farmed back out again, and the Swedes are astonished. ‘Why do you do that?’

Who knows?

Of course, people in Nordic communities do grumble, moan about taxes and support mergers amongst the smallest municipalities. But they view councillors as respected neighbours, not ill-informed strangers, and expect the bulk of day-to-day decisions about their lives to be taken by people they know. And mergers still leave Nordic municipalities small by Scottish standards – what’s distressingly large for Norwegians is still a tenth of the Scottish average council by population size.

What is it about ‘local’ that the traditional left seems to find mildly embarrassing? Place has shape, history, limits and baggage which can produce sentimentality – but it also provides the small, compact scale and grounding particularity that facilitated radical change in Eigg, Assynt, Gigha and Storas Uist. Karl Marx shaped the thinking of generations by suggesting the urban proletariat would be the inevitable agents of transformational change – surprising then to find that a bunch of Highlanders could seize the moment and turn the tide of history without a high-rise block, pub, office or the other trappings of urbanism in sight. In the local domain you need personality (or relations) not a clipboard. It’s a place with quirks not rules; subjectivity not objectivity and attachment not cool, professional detachment. Community cannot be established by wild-eyed radicals with abstract theories but is built slowly by stories, memories, first names, being there and knowing people. For some whose reforming zeal arises from a deep-seated uneasiness around people – and in my experience there are a few very shy souls who’ve turned that personal temperamental issue into the centrepiece of their politics without even knowing it – the local sphere is an uncomfortably informal, low key arena whose modest aspirations for change invite parody and ridicule. For such people, ‘local’ is broken… Local is broken pavements and a politics of dogs’ dirt, populism and litter. It’s nimbyism – Alan Partridge stuck forever inflicting the hits of yesteryear on people who are off the pace and behind the times. That’s the stereotype – and sometimes it’s true for the very political reason that rural councils have often been controlled by the landed gentry.

The Duke of Buccleuch and the Duke of Roxburghe between them held the convenorship of Roxburgh County Council for 43 years between 1900 and 1975. The great Borders landowners were able to exercise influence directly in this way but also indirectly through the offices of Sheriff Depute and Commissioners of Supply. They were in addition Lord-Lieutenants of the counties and Commissioners of Peace. In 1918 the convenor of Roxburgh County Council was the Duke of Roxburghe; his Vice-Convenor was the Duke of Buccleuch. In 1975, before the County Council was abolished, the Convenor was the Duke of Roxburghe; the Duke of Buccleuch and Baronness Elliot were also on the council. Nothing much had apparently changed.7

In the Scottish countryside lairds kept a firm grasp of local politics until the reorganisation of local government in 1974.8 Even then, the kind of people selected as candidates often echoed the status of the landowner. In the 1970s, Highland councils had the highest proportion of ministers and churchmen standing as councillors, the highest proportion of men elected and the highest proportion of councillors elected unopposed. Not a radical environment– that’s perfectly true. But some cities historically were not much more militant:

In late 19th century Edinburgh, for example, the lawyers and professional men withdrew from local, political affairs, leaving the Town Council to be run by small landlords and shopkeepers. The kind of politics they indulged in were largely defensive and negative. Because local revenues were raised by property taxes – the rates – many small property owners only got themselves elected to the local council to control the level of public spending (Dickson and Treble, 1992).

In short, local councils have often become fiefdoms for the great and the good – the most effective arena for domination of less powerful Scots by more powerful Scots. Not a place where genuine democracy has thrived. For centuries Scots have become active citizens elsewhere by ensuring new places and local conditions are nothing like the Scottish places that shaped them.

Is the progressive answer to keep running off to a larger place where the wearisome gridlines of ownership, control and permission are a little less clearly laid down? Is the answer to downgrade the local dimension of life – or to fix it, so the formative years of the next generation are not spent learning all the things that cannot be done in Scotland because…

Now it’s true that many communities at present are not mini nirvanas. All too often, in the absence of real democracy, gatekeepers and cabals have taken over. There’s no clear idea of what community development is for since it seems to duplicate what councils should be doing. Many community radio stations find retired incomers have taken over. And whilst Development Trusts are thriving, they make huge demands on time and voluntary resources.

Local is haphazard because it exists in the nation’s collective blindspot – not because place is irrelevant and community impossible.

The answer is more structure, more democracy, more functions, more expectation, more asset transfers, more connection, more grassroots integration and more power – not less.

Government leaders and distant bureaucrats cannot act endlessly as our absent mentors and proxies. Communities need to do some light, medium and eventually heavy lifting ourselves. But no athlete ever started a long race without a warm up. Currently communities who want a share of the action must run the equivalent of a democratic marathon after decades struggling to run for the bus. Scots have such a slender grasp on local power that participation in the community often means no more than buying a paper.

And that too has political ramifications. Surveys find professionals have fewer local attachments, go less frequently (if at all) to local pubs and shops and socialise less with neighbours. ‘A life less local’ describes the governing class who spend their lives devising services, frameworks, health messages and desirable realities for everyone else. That’s problematic.

Some say a plethora of small municipal councils would cause waste, duplication, jobs for the boys, postcode lotteries, chaos and soaring expenses claims from second-rate interfering amateurs. Of course, there would be problems with radical decentralisation – we’re all out of democratic practice. But the evidence from development trusts and other countries is that we can pick up the ropes pretty quickly.

It’s time for the Scottish Government to admit that scale hasn’t ended the scourge of poverty and disadvantage – it’s just meant decision makers don’t have to bump into it.

In Scotland, places are dying because of remote, wrong-sized governance despite being full of human talent, capacity, problem-solving energy, history and natural resources.

And yet place is revolutionary because place is where people are. And empowerment and self-determination are principles for everyday life – not just the independence referendum.

—

1 Andy Wightman, ‘Scottish Six Lectures’, Edinburgh Festival Fringe, 2012.

2 http://www.johnstoncollection.net.

3 Jimmy Reid Foundation, Silent Crisis Report 2012.

4 The World Values Survey has been monitoring values in over 100 countries since 1981.

5 http://www.economist.com/news/special-report/21570835-nordic-countries-are-probably-best-governed-world-secret-their.

6 http://www.scotsman.com/news/politics/top-stories/councils-in-scotland-spend-less-on-local-firms-1-2992710.

8 A. Morris, ‘Patrimony and Power’, Unpublished DPhil Thesis (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University, 1989).