CHAPTER TEN

Whose Culture is it Anyway?

SCOTLAND IS AWASH with culture.

When the independent Scottish state was formally dissolved in the Treaty of Union, our culture became the chief standard bearer of Scottish identity just as a large injection of British thinking was added to Scottish life – especially to the lives of the elite. Crackdowns, clearance and emigration after Culloden removed Gaelic and Scots speakers along with their songs, outlooks, traditional instruments and folk customs. British cultural values became the safest to espouse and highbrow English traditions the most profitable to learn. And yet, Scotland’s native traditions somehow survived to be revered, adapted, neglected, forgotten, misrepresented and rediscovered all over again. But in this bubbling mix one thing has been constant – the power wielded by funders, civil servants and arts administrators over what to show and what to store, what to expose to a Scotland-wide audience, what to confine to ‘experimental spaces’ and what to simply ignore.

There are simply too many artefacts, too many traditions and too many distinct cultures to fit into the pint pots of funding streams, exhibition space, official events or time in the school curriculum. There is no way to avoid choice. And choice is a political act.

I began choosing early, ‘correcting’ history books which seemed to confuse Britain, England and the UK. Despite the neatness of my work I was suspended. My first post-school boyfriend was a Glasgow painter who shared a flat with ‘New Glasgow Boy’ Adrian Wiszniewsk. Later I married a poet whose performances allowed me to bump into Iain Crichton Smith making toast in an Oban hotel at three in the morning, Hamish Henderson in Sandy Bell’s bar, Angus Peter Campbell, the uncompromising Gael, and the effervescent Meg Bateman, whose love poetry was often a gentle antidote to all the men. I once interviewed Norman MacCaig for a radio celebration of Hugh MacDiarmid’s life, argued about feminism with the ‘young’ David Harrower, stayed with the editor of Chapman, Joy Hendry, watched the late Michael Marra nervously prepare to sing at Glenuig, first-footed Capercaillie’s Donald Shaw and Karen Matheson when they lived in Partick and shared choppy boat crossings to Eigg with loyal buyout supporters, Shooglenifty. Scottish artists and Scottish culture have always been accessible.

Lucky to sample the incredible wealth of Scottish song, poetry, writing, painting, sculpture and architecture early in life, I was baffled then infuriated to see how few artists could make a living, let alone a mark, on mainstream Scottish consciousness – no matter how sought after outside Scotland. Opportunities to reach beyond ‘specialist’ audiences, or receive more than travel expenses here were extremely limited – even for giants in their own fields. When the renowned Shetland fiddler Tom Johnson died in 1991 I was in Ireland and watched a one-hour tribute programme on rte. Back home on BBC Scotland, I found nothing. Mercifully, thanks to the explosion of book festivals, traditional music events like Celtic Connections, volunteer learning projects like the Gaelic Feisean and the internationally acclaimed National Theatre of Scotland – all established after years of lobbying by artists – the situation is now better. Scotland still isn’t Ireland, where artists effectively live tax-free. But Scottish artists are taken more seriously – especially when they manage to dislodge directors of Creative Scotland.

And yet the dilemma remains. Which artist to choose? What performance to fund? And who should decide?

In 2012 Alasdair Gray hit the headlines after protesting about the high number of non-Scots in top arts jobs making these important judgement calls. He was particularly critical of folk who come and go without getting Scotland under their fingernails. All hell was let loose online and one of Alasdair’s ‘colonists’, Vicky Featherstone, wrote about feeling bullied because of her English origins when she became the first Director of the National Theatre of Scotland. It all got very personal, very fast. The terms employed in the book chapter from which the controversial newspaper article was taken were definitely loaded. ‘Settler’ has the ugly connection of ‘white settler’ – ‘colonist’ has the unattractive overtone of colonialism. But there was a choice. Readers could react to Alasdair’s terminology – or focus on the crucial subject he raised – rather lost in all the furore.

Is there a disproportionate number of non-Scots in top jobs, particularly in culture and the environment?

It seems strange that merely asking the question prompted immediate cries of anti-English racism. Most nations monitor the distribution of benefit – it’s the only way to counter elitism and understand the impact of public policy. Only the very perverse would ascribe sexist motives to those who thought most speakers at the Yes Campaign launch were male. It was patently true.

But cultural outlook is far harder to define. Perhaps – to re-apply Bourdieu – it’s easier to say that high-profile managers have a certain habitus. And ‘British’ values are probably a good measure of suitability. Now I say that and know there’s absolutely no easy way the observation can be measured. But that doesn’t mean the issue is any less real or important.

So by way of illustration, this is where Gary Tank Commander comes in – a 2012 BBC Scotland sitcom in which a bunch of soldiers find ways to pass time in the unglamorous surroundings of a Glasgow barracks, waiting to do combat in defence of Queen and Country. In one episode, the eponymous hero holds up a small orange and asks if it’s a clementine, tangerine or satsuma.

‘Naw,’ he concludes. ‘It’s jist a wee orange – they’re all wee oranges.’

Now this either prompts a laugh or you don’t get it. Scots don’t see much value in learning the tiny differences between exotic objects. Instead they save their energies for the vigorous use of metaphor. Thus, you might be thinking, see this argument – see mince.

But can a leader, top person or manager really be someone who (defiantly) calls mandarins ‘wee oranges’ in the upper echelons of society? Can you say ‘aye’ in a Scottish court without being done for contempt (it did happen in 1993)? Can Scots confidently bring their ‘whole selves’ into the limelight – and particularly into the highly contested domains of arts and the environment where ‘proper sounding’ people abound? Of course issues of entitlement affect every part of the class-ridden UK. Perhaps that’s why Bradley Wiggins was a shoe-in to win Sports Personality of the Year 2012. He is that very rare thing, a working-class lad made good without corners visibly knocked off in a sporting world dominated by those with time and parental cash.

And this is where Dirty Dancing comes in. I’m not ashamed to admit (well I am a bit) this is my favourite film and not just because of the late Patrick Swayze. The best line in the film was the exchange between the cringingly named ‘Baby’ and her dad after she confessed to having a fling with Pat. ‘You lied too,’ she says. ‘You told me everyone has the same chance in life, everyone deserves to be treated equally. But you didn’t mean everyone. You just meant people like you.’

And that of course, is the moment kids really grow up. When they realise adults say a lot of things they don’t actually mean. Life should be fair – but in practice it isn’t. Boundaries and limits are quickly established, learned behaviour helps to firm up that ‘place in life’ and peer-group policing takes over. Thus girls can do whatever they want at school – as long as they all wear pink anoraks. Kids from backstreets can make it to the top if they lose unsuitable friends and accents. And Scots can mumble away about the obscure-sounding people and places that have inspired them and still get top jobs. Except they don’t. If this was easy to measure or remedy, Scots would have cracked inferiorisation, a problem observed across the world where less dominant communities hesitate before asserting or developing their own values. So of course it’s impossible to say what proportion of top appointees ‘should’ be Scots, impossible to say which individual non-Scots have sufficiently understood the Scottish zeitgeist to become ‘honorary Scots’ and which are stubbornly ‘rolling out the barrel’ in defiance of all local tradition. Impossible to prescribe – and undesirable. Change takes time, patience, encouragement, small step promotion, risk and – above all – balance. The last thing that would be natural for a trading nation like Scotland, is an unwelcoming reception for anyone who wants to come, visit, live or leave. The last thing that would ever be appropriate in this ‘mongrel nation’ would be a state-prescribed monoculture of (inevitably) synthetic Scottishness to replace the current and decidedly synthetic model of ‘Britishness’.

But the question still remains. Is Scottish culture in the hands of Scots?

It’s a subjective argument – but that doesn’t make it any less important. Just much, much more sensitive.

Before devolution, the average Scot stood on the sidelines and watched for decades – maybe centuries – as people with different habits, accents, vocabulary, cultural preferences, reading material, university backgrounds and presumptions about life got almost all Scotland’s top jobs. Of course some of those ‘leadership voices’ were ‘educated Scots’. But educated in what? Scottishness? Indeed, what is that anyway?

Strangely, I’ve never heard Scottish culture better described than by a Yorkshireman I once interviewed for a Radio 4 programme. Church of Scotland Minister Robert Pickles headed to Fife more than two decades earlier and still admires what he calls the ‘Scottish mentality’:

Celts live for the day. Not money. It’s not what you’ve got but who is related to who and who you know. Scots are very family-oriented and they are people with many layers. Scots are like oil – there’s a lot more going on underground. There’s a spirituality here I love. And less of a fuss about material things because there’s an understanding of a more fundamental connectedness – music and art evoke very deep feelings. Celtic knotwork is intricate – so are the Scots. There are fewer layers in England. Scotland has been preserved from that blandness. Life here is far richer… and in that respect Scotland is 30 years behind. But not in a bad way.

I interviewed many people for that programme and yet Robert’s wistful description of the Scots’ intense experience of music is the image that remains. Because it rings true.

A few years ago I sat at the back of a packed function room in the Dark Island Hotel on Benbecula for a piping concert. A large crofter sat in front of me, a freshly washed and starched-looking white shirt drawn tight as a barrel across his massive back and damp hair, fresh from the shower – further evidence of the importance he attached to this event. As the lone piper started to play pacing slowly up and down the room, the great back of the crofter swayed and heaved. At some moments he was softly singing along, at another moment quietly wiping away a tear – and he was not alone.

Surely this easy and emotional response to traditional music is one of Scotland’s most authentic cultural legacies – and yet despite several lifetimes’ effort by traditional musicians, it’s still the poor relation for funding compared to the ‘Victorian art-forms’. That has some upsides – the voluntary effort needed to sustain the Gaelic Feisean movement has become part of its spontaneous, un-stuffy charm. A group of Sami writers from Arctic Norway I guided round Skye was astonished by an un-rehearsed, impromptu performance by Talitha MacKenzie, Christine Primrose and Margaret Bennett at a ceilidh in the Gaelic College on Skye. And even more impressed the event was not organised by a full time music co-ordinator financed by the local municipality. Stalwart promoter Duncan MacInnes snorted wryly at the very notion. ‘Not a chance.’ The selfless voluntarism that underpinned the ceilidh was commented on for days – until it was overshadowed by a crofter who came to the rescue after the tour bus unaccountably burst into flames in a car park above the Talisker distillery. Murdo arrived quickly in a vintage bus kept for emergency school runs, drove us to lunch in Dunvegan without asking for payment, and afterwards persuaded a Skyeways colleague to ferry us back south again. The entire trip was regarded as a precious gift, a possible demonstration of shamanic powers (still very valued by Sami people) and a minor miracle.

There’s no doubt the voluntary effort required to keep traditional culture alive has become a vital part of its character. It’s also become an excuse for putting Scottishness second. So it wouldn’t matter who was in charge of Scottish culture if we were all singing from something like the same hymn-sheet. We aren’t.

When there are two competing realities, but space for only one narrative, it’s the official British version that tends to prevail – and since 1707 that has only sometimes coincided with Scottish reality. Nowhere have the two diverged more strongly than in the portrayal of the Scottish ‘wilderness’. The London-based Scot James Boswell once said Voltaire looked amazed when he announced his intention to visit the Scottish Highlands: ‘He looked at me as if I had talked of going to the North Pole.’ The fearsome nature of Scottish weather and landscape had long kept visitors away until Queen Victoria braved the elements to set up a second home at Balmoral. Deer stalker-clad southerners and wealthy lowland Scots followed her north to shoot deer and grouse in deer ‘forests’ newly emptied of local people. Aided by the romantic novels of Sir Walter Scott, Scotland was soon transformed from a place with nothing to see before 1760 into the most fashionable holiday location for the wealthy in Europe. Landowners often cleared labourers cottages and sometimes whole communities to improve the view from their country seats, a practice attacked by English reformer William Cobbett, who made a tour of Scotland in 1832. He was outraged that Edinburgh – which he regarded as the finest city in the world – was not surrounded by thriving agricultural villages because aristocrats kept their estates empty, rural and ‘unspoiled’.

He also raged against the Clearances, arguing that:

It may be quite proper to inquire into the means that were used to effect the clearing, for all that we have been told about [Scotland’s] sterility has been either sheer falsehood or monstrous exaggeration.1

An outraged visitor could say what local Scots could not. And yet the British narrative could not contain such a critique so Cobbett was roundly ignored.

Sir Walter Scott and Queen Victoria decided to reinvent the kilt. Less than a century earlier, in the aftermath of Culloden, wearing it was enough to get you killed.2 One object, two stories. Indeed, thanks to the Scottish habit of deferring to the tired, toothy old war horse of Britishness at every turn, there are two stories about nearly everything.

Take piping, place-names and Scottish country dancing. The 1746 clampdown and associated loss of Clan Chief power, along with clearances and emigration led to a near collapse in the old piping traditions. The MacCrimmons’ piping school for example, closed down in the 1770s in a dispute over rent with the Chief of the Macleod’s, not helped by falling numbers of would-be pipers as Chiefs struggled to spare pipers for the years it took them to train.3 But while traditional clan piping was in decline, piping in Scottish regiments of the British army was on the rise. As Calum MacLean puts it in The Highlands:

The Hanoverian regime recognised the fact that every Gaelic speaking Highlander was a potential nationalist, Jacobite and rebel. Towards the end of the century, there was formulated the brilliant policy of enlisting the ‘secret enemy’ to destroy him as cannon fodder. Highlanders were again dressed up in kilts and, by the ingenious use of names such as Cameron, Seaforth and Gordon, old loyalties were diverted into new channels. The end of the Napoleonic wars necessitated another fresh policy… the horror of the Clearances was now to be let loose on the luckless Gaels.4

Meanwhile there were (at least) two versions of place-names as English-speaking map makers and ‘civilisers’ found their way to the most distant places of Scotland and inevitably changed what they found. They didn’t speak Gaelic and locals didn’t speak English. The resulting misunderstandings, misnamings and resentment was documented in Ireland by the playwright Brian Friel in his play Translations. The same thing happened in Gaelic speaking Scotland and in the 1881 Census (the first to count Gaelic speakers) that accounted for 60 per cent of Highland Perthshire alone.

Likewise with dance, many of the most popular ‘Highland Dances’ sprang from the English military barracks, not ancient Scottish tradition. The origins of dances like the Gay Gordons and Dashing White Sergeant are pretty obvious when you pause for a second to consider the names. But what of it? ‘Scottish’ country dancing is part of Scotland’s story now, isn’t it? Quite so. It’s just that the Balmoralised, pacified face is accepted, packaged and exported as Scotland’s genuine article – whilst the old Gaelic clan ‘warrior’ face has long been marginalised and feared as backward, slow or vaguely threatening. Unless of course it’s worn by Mel Gibson.

This fabulous complexity – all of it – is unquestionably Scotland’s story. A massive, rich, chewy cultural heritage with a central issue grinding away at its core: whose story to choose?

As the Englishman Edwin Landseer was painting the classic image of the Scottish Highlands, The Monarch of the Glen, in 1851 thousands of real Scots were being cleared from real hillsides to make way for deer. This idealised hunter’s image of the noble beast became the classic portrait of deer in the Highlands – for some. But for native Gaels, that place would always be occupied by a different man – Duncan Ban MacIntyre a century earlier reciting a poem from memory to a pibroch pipe tune which described deer and mountain life in a very different way. ‘In Praise of Ben Dorain’ was transcribed by the son of a neighbouring minister, and much later translated into English by Hugh MacDiarmid and Iain Crichton Smith who said of it:

Nowhere else in Scottish poetry do we have a poem of such sunniness and grace and exactitude maintained for such a length, with such a wealth of varied music and teaming richness and language. The devoted obsession, the richly concentrated gaze, the loving scrutiny, undiverted by philosophical analysis, has created a particular world, joyously exhausting area after area as the Celtic monks exhausted page after page in the Book of Kells.5

And yet, despite such fulsome praise from the venerated Crichton Smith, educated Scots probably don’t recognise the name of Duncan Ban MacIntyre but have seen Landseer’s Monarch. Whose reality gets pride of place? The official or the unofficial, the British or the Scottish? Indeed, the Scots or the Gaels?

Perhaps, you might think, a cheerful amalgam of all outlooks and artefacts is possible. Why not let a thousand flowers blossom? After all, in the modern world many cultures co-exist, enriching and enlivening one another.

That’s true.

But choices still have had to be made. For our national galleries there’s just too much to fit in. With limited funds and only so many square metres of gallery wall or museum floor, one artefact taking pride of place means several others must go into storage. What goes and what stays? Indeed, is an institution like the Scottish Portrait Gallery meant to capture the zeitgeist of modern Scotland at all? Reaction to the gallery’s renovation has been overwhelmingly positive since it re-opened but I found myself mightily disappointed by the relative absence of modern Scots on display and slightly bored by ‘imperial history.’ Hey ho, I thought. That’s just me.

But then six months later, the genial giant and subversive sculptor George Wylie died and I found myself mourning his absence from life… and from our National Portrait Gallery. George was so universally popular he managed the near-impossible on the day he died – a smiling portrait on the front pages of both the Herald and Scotsman newspapers uniting east and west.

George also fused together everyday life, industrial heritage and Glasgow humour like the master welder he was, with installations like the Straw Locomotive, the 80-foot Paper Boat, the giant nappy pin outside the Glasgow Maternity Hospital and the Walking Clock outside the Bus Station. When artwork for the M8 was first proposed, George suggested an empty candelabra at the Edinburgh end and lit candles at Bailieston. Cheeky monkey.

In a world where ‘high culture’ has long been the preserve of the few, George was a feisty, thrawn, characteristically Scottish and democratising force. Everyone who saw his sculptures could hold an opinion about art. The Straw Locomotive hoisted up on Glasgow’s Finnieston crane was fun, daft, spectacular and – swaying gently over the largely shipbuilding-free landscape of the Clyde – profoundly sad. I think it’s no overstatement to say the man was loved. And yet, at the time of writing, there is no image of George Wylie on display in Scotland’s Portrait Gallery. Indeed, as far as I can see, other important artistic contributors to 20th century Scotland are missing too. Poets like Norman MacCaig, Sorely MacLean, Iain Crichton Smith and Hamish Henderson. People like the current super-league of artistic talent from Makar Liz Lochhead to Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy and Booker prize winner Jim Kelman. In fact, when you start to think about it, the list of well-loved, internationally respected, larger than life, modern Scots missing from the walls and plinths of the Portrait Gallery is huge. Of course there are reasons for that.

The Gallery was banned from commissioning portraits of living Scots until the early 1980s, so the collection is inevitably skewed towards high quality older pieces. But once again, there’s no getting away from the tyranny of choice. The Gallery owns 3,000 paintings and sculptures, 25,000 prints and drawings and 38,000 historic and modern photographs. So even with extra space, tough choices have to be made. The hopelessly inadequate ground floor space means sculptures and portraits of modern Scots are kept in storage and shown on rotation. I’m left with the feeling ‘my’ Scotland isn’t in there. More importantly, I didn’t expect it to be. Perhaps I’m not alone.

A Telegraph critic praised the Gallery’s renovation but asked, ‘where is the former Lord Chancellor Derry Irving or, for that matter, Scotland’s First Minister, Alex Salmond? Most surprising of all is the absence of both Tony Blair and Gordon Brown.’

Well, quite.

Why are larger than life modern Scots missing from the Scottish Portrait Gallery? Perhaps the answer lies in the streets all around.

Edinburgh’s New Town is the crowning achievement and physical embodiment of Britain’s ‘finest hour’. After Culloden, the need to expand beyond the overcrowded Old Town combined with a desire to appeal to the triumphant Hanoverians and reassert the primacy of the newly created and almost toppled British state. So in 1767 James Craig devised a New Town plan which reflected the ruling elite’s love of classical antiquity – and street names that reflected their naked power.

George Street – the largest and most prestigious thoroughfare – was named after King George iii. Queen Street was named after his wife. Princes Street, originally planned as ‘St Giles Street’, was named after his sons, Hanover Street after his family and Frederick Street after his dad. St Andrew’s and St George’s Square (later Charlotte Square) were named after the patron saints of the two recently unified nations, while Thistle Street and Rose Street represented their national emblems.

Welcome to Edinburgh, where Britishness is still working its way through Scottish culture like a kidney stone.

Take Holyrood.

Edinburgh’s controversial parliament building incorporates Queensberry House, whose most famous resident was James Douglas, 2nd Duke of Queensberry. In 1707, when the Duke signed away Scotland’s independence in the Treaty of Union, riots allowed his violently insane son to escape the room in which he was normally locked and roast a servant boy alive on a spit in the kitchen. The Earl of Drumlanrig had started to eat the boy before he was discovered and caught. No charges were brought, and ‘The Cannibalistic Idiot’ was whisked across the border to England. Astonishingly, the oven can still be seen in the Parliamentary Allowances Office.

Why did architects decide an 18th century murder scene was worth saving at such great expense? Later in its career, Queensberry House was deployed as a hospital, barracks and refuge for ‘female inebriates’ until S&N Breweries and then the Parliament bought the entire site. A contractor told me that behind the plaster, Queensberry House was a surprisingly poor building – assorted rubble rather than dressed stone. I know arguments about building quality are subjective, but one thing’s for sure. The decision to retain this List A ‘historic’ building within Miralles’ new Parliament contributed to the complexity, delay and massive bill which in turn nearly destroyed the early authority of Scotland’s new Parliament. The Duke of Queensberry might have been rather amused. All that effort to preserve a building made special only by the appalling barbarity of his murderous son. In the old days, nobles and barons had the power to stifle dissent. Nowadays an ‘A’ listing does the same job quite nicely. In Edinburgh, ‘heritage’ is King. And its subjects dare not ask whose heritage we are preserving.

Edinburgh contains contrast – as any good capital city should. It also contains a contest. Holyrood sits astride a cultural fault-line as real as the geological rift that produced Arthur’s Seat and the Castle Rock. Just as the gathering place of the world’s oldest parliament sits astride the clash of tectonic plates at Thingvellir on Iceland, so 900 miles further south, the world’s newest parliament straddles the place where imperial Britain and modern Scotland meet, sometimes mingle and sometimes hardly touch.

The result is a physically awe-inspiring city that sometimes feels like it belongs to someone else.

Old Town and New Town, medieval and Georgian, formal and informal, Kidnapped and Trainspotting, Opera and step-dancing, the Usher Hall and Sandy Bell’s, Morningside and Leith, Royalists and Republicans, Burke and Hare and Jekyll and Hyde – every conceivable contradiction in Scottish society grumbles away in Edinburgh. Quietly.

I suspect Labour’s First Minister, the late Donald Dewar, had a profound fear of stirring this hornet’s nest by building a Scottish Parliament that might rival the Britishness of the New Town. The (very) well-rehearsed argument about the location of the Scottish Parliament suggests he rejected Calton Hill as a possible site because it was a ’nationalist shibboleth’.

If that’s true, what did it mean? Almost every building on Edinburgh’s elegant Calton Hill dates from the Enlightenment – when Scottish luminaries rejoiced in the description ‘North British’. Greek architectural references abound; the National Monument is based on the Acropolis and the Royal High School has Doric columns based on the Temple of Theseus. Why would the choice of such a location tilt a nation inevitably towards introversion and petty nationalism? Waterloo Place, Royal Terrace and Regent Road – the unrevolutionary character of the wide, elegant streets flanking Calton Hill is self-evident.

The Royal High School itself was converted by Jim Callaghan’s Labour Government at the cost of several millions to accommodate a Scottish Assembly Debating Chamber after Scotland’s first devolution referendum in 1979. A nationalist shibboleth? Hardly.

Perhaps it was actually Calton Hill’s suitability as a parliament location that bothered Donald Dewar. According to the civil servants, a parliament there would have created:

A magnificent historic setting in an accessible city centre location: highly visible, adjacent to the Scottish Office, approachable through a civic space comparable with other European capitals, and without causing any major traffic problems.

‘Comparable with other European capitals’. Without realising it, this advocate probably sealed Calton Hill’s fate. Labour’s devolved assembly was not to be compared with other European capitals. It was to be a workaday place – a big council, not a small parliament. Devolution could have created a fabulous British building on a hill studded with British architectural gems. But instead a parliament was built in a low-lying shoebox of a space (or rather, the constrained footprint of a disused brewery) in case it offered a new centrepiece of Scottish culture and an emotional rallying point for Scots.

It all speaks volumes about Labour’s early lack of confidence in devolution. It speaks volumes too about the territorial minefield that is Edinburgh – a profoundly divided city which could be a cold, unloveable place, trapped in the empty fabrication of ‘Britishness’ but for the humble tenements which have been Edinburgh’s salvation binding the city’s inhabitants together.

Coveted and slightly invaded during the summer, Edinburgh is Scottish all winter long, in the snell wind, in each quick stolen glance down the wynds towards the radiant blue or scudding grey Firth, at bus stops beneath polished outcrops of volcanic rock or on the sharp, whin-covered ridges of Arthur’s Seat and the Crags.

Edinburgh is not just the British Athens of the North. It is also our spiritual mountain home.

Meanwhile, Glasgow expends its energy mediating another relic of Britishness – an endless reworking of the Battle of the Boyne in which Protestant King Billy gubbed Catholic King James.

If Edinburgh revisits the failure of the Jacobite challenge at every New Town street corner then Glasgow re-enacts the struggle for Irish Independence at every Old Firm match.

Four times a season, for more than a century (until Rangers’ recent relegation) two sets of Scottish football fans have gathered to hurl insults and sing the Famine Song and ira songs across the terracing. Chants of ‘orange bastard’ and ‘fenian scum’ flew backwards and forwards and large numbers of police were employed to enforce a strict segregation of fans, reinforcing the idea that nuclear meltdown would occur if the two sides should ever meet. Not long ago, a Catholic player was cautioned for crossing himself on the pitch. An alien beamed down from another planet might conclude that Scotland is emerging from some kind of civil war.

He would be right. But it has nothing to do with religion or Scotland – at least not directly – and everything to do with the Irish Independence struggle. Listen to the songs and read the slogans. Whether it’s the Billy Boys, Fenian B******s, No Surrender, Tricolours, 1690, Union Jacks or Red Hand Salutes – Irish history is being re-enacted in Glasgow every weekend. Why can’t Glasgow leave Irish history alone? Or find symbols of Scottish history to fight over? Simply put – because the Irish won. And for many Scots, the guilty secret is that their own country didn’t. This is the love that dare not speak its name.

Celtic supporters identify with cousins who sent the British packing (though ironically, Catholics have traditionally voted Labour). Rangers fans identify with the Britishness that built an Empire and transformed the Clyde’s Protestant craft and design tradition into a world-beater (though statistically many of them voted SNP at the 2011 Holyrood elections).

Of course the whole of Scotland does not revolve around Glasgow, the whole of Glasgow does not revolve around football and the whole of the Old Firm’s loyal support is not preoccupied with religion. The Irish Independence struggle is not even consciously present in sectarian minds. But then, neither is religion.

As researchers from Edinburgh’s Queen Margaret University College have found, fans on both sides can chant ‘Fenian’ and ‘Hun’ all match long, and yet feel completely protected from allegations of sectarianism because they know there is absolutely no religious component to their behaviour.

Most genuinely religious adherents were long since deterred from attending live football by the amount of swearing they had to endure to watch the Beautiful Game. Only a tiny minority of ‘Fenians’ or ‘Huns’ have any interest in European history or knowledge of Ireland. Even fewer want to acknowledge that most members of the starkly divided, paramilitary groupings they will ‘support forevermore’ are doing their best to bury the hatchet and leave sectarianism in Ireland’s past.

Nope – that’s all too complicated.

Nowadays the average chanting Glaswegian is simply claiming membership of a tribe. His one. Part of whose raison d’être is to antagonise another tribe. Their one. It may get embellished with symbolism because even half-remembered points of religious distinction are less shameful than the real reason for the drinking, screaming, violence and hatred. Nothing.

Except ‘us and them’.

Any original differences are long gone but the adrenalin rush and feeling of identity through intense loyalty and confrontation is still powerful.

Are the battle lines really drawn over religion, background or race? Probably not. The underlying problem is the absence of a larger, single, uncontentious, unifying Scottish identity. British and Irish. Scottish and British. Protestant and Catholic. And now Nationalist and Unionist.

Two sets of values have been operating in Scotland for so long that schism and confrontation seem natural – even necessary to help separate the sheep from the goats, us from them, family from strangers. The tendency to divide is like an instinct now – an instinct which makes no sense in such a small country.

Interviewing punters about sectarianism for a Radio Scotland series in Glasgow’s East End some years back (neutrally dressed in purple), I visited a Celtic bar where the Protestant owner had to tolerate Scottish fans singing Republican songs whilst Scottish soldiers were being killed in Northern Ireland. ‘Where was their loyalty to their ain folk?’

In another Celtic bar I asked if punters could tell Protestants from Catholics on sight. Of course they could…

‘Prods are right wing – Tories, fascist even.’

‘Catholics are socialist – there’s Che Guevera tattooed on my arm.’

‘Prods are just bad craic – they must have rubbish parties cos they’ve no decent songs, no tradition.’

Since this was all very good-natured, I invited the assembled drinkers to guess my religion.

‘Well, you’re a big woman – well fed. I’d say you’re a Prod.’

‘C’mon now, she’s been game enough to wander in here talking about sectarianism. I’d say she’s a Tim.’

When my name didn’t offer any clues, there was one final assessment;

‘Make-up, dyed hair and a phoney Coney [mock fur jacket] – you’re a Prod.’

Correct – on the upbringing at least. It was hilarious banter about dangerously rigid stereotypes.

Both ‘sides’ in Glasgow have carved out entire personalities for the ‘other.’

The rest of Scotland looks on. A few cup finals ago, victorious Hibs fans sang the entire repertoire of the Proclaimers. This is also Scotland. Joyful, exuberant and funny. This is the Scotland most Scots want to belong to – not the 33rd county of Ireland that’s developed in the west of Scotland.

Sectarianism – like drink – is not the biggest problem in anyone’s life, but it conveniently distracts attention from what is, and divides those who most need to make common cause. In 1935, A Scottish Journey by Edwin Muir was published and he observed:

Glasgow is not Scotland at all... it is merely an expression of Industrialism, a process [which has] devastated whole tracts of countryside and sucked the life and youth out of the rest, which has set its mark on several generations in shrunken bodies and trivial or embittered minds.

Almost 80 years later, Glasgow is no easier to understand. Glaswegian men are dying from the effects of drink at twice the rate of everyone else. The rest of Scotland is more like the rest of the UK. But Glasgow is on a different level altogether – it’s drinking to forget. I almost wrote Glasgow is in a different league – and that’s half the trouble. In Glasgow, a willingness to embrace excess is part of the culture. It still brings status – even if it also brings broken health. That downside is regarded as a small price to pay for a moment of action – away from the dreary, passivity of everyday experience. The worship of excess is very Celtic. By contrast, prudence and moderation is regarded as very British.

So it’s hard for anyone to confront this worship of excess. Summarised succinctly in the BBC Scotland sitcom, Chewin the Fat: ‘You’ve got tae drink.’

‘More is more’ might be the best way to encapsulate Glasgow culture with a ‘grab life while you can’ outlook developed over centuries of manual work in factories and shipyards. Those workplaces have largely closed, but the culture has not. Glaswegians are easily tempted to behave like powerless wage slaves for whom tomorrow may never come.

Why is that? As long as mainstream, time, money and attention is soaked up with empty reverence for an imperial past, it justifies the confrontational gallusness for which Glasgow is renowned. It’s as if Scots fear that curbing the Glaswegian tendency to excess will turn the bold Weegies into the North British. And that will hopelessly weaken Scotland’s cultural mix.

With Glasgow re-enacting the Battle of the Boyne on the terracing and Edinburgh streetscapes frozen in the aftermath of Culloden, it’s astonishing that any distinct Scottish culture exists at all. And yet it does. Big time.

Partly because Britishness seems to be no more than the preoccupations of south-east England writ large. Partly because (mercifully) there’s more to Scotland than Princes Street, Hamden and Ibrox but also because Scots can tell a spade from a shovel.

Britain is a state with a tax base, not a nation with a culture. Britain has a set of widely experienced administrative arrangements and the formal trappings of statehood (flag, currency, army, navy etc) but it’s the constituent nations of Britain (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) which have distinct cultures, histories, political cultures, languages, civic structures and (to varying degrees) distinct institutional frameworks in law, education, media and local government.

As Manuel Castells puts it:

Nationalism, and nations, have a life of their own, independent from statehood, albeit embedded in cultural constructs and political projects.6

So Scotland commands emotional loyalty because it’s a nation. Britain commands tax returns because it’s a state. Neither Scotland nor England is a state – no matter how often the nation of England and the state of Britain are used interchangeably.

Indeed, as Michael Gardiner observes:

England, a part of the UK, is a minor nation crippled by the idea of its own majority. 7

It may sound messy. But as sociologist David McCrone observes, multination-state Britain is actually in good company:

[There is] a plethora of political and cultural forms: stateless nations, nationless states, multinational states, shared nation-states, as well as a few – possibly only around 10 per cent – genuine nation-states in which the political and cultural realms are reasonably aligned.8

Britain is not a member of that ten per cent club. It consists of four stateless nations, not one nation state. And that’s a vitally important distinction. Four nations stopped being states at different times in history – but they never stopped being nations exerting cultural clout. Indeed, as David McCrone has observed:

Following the Union of 1707, Scotland was left with a deficit of politics and a surfeit of culture.9

Precisely. Thus many Scots consider themselves to have a British ‘state’ identity and a Scottish ‘national’ identity and are remarkably clear about the difference.

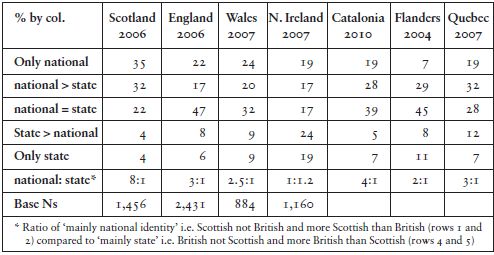

Figure 22: National identity in comparative context.

A team of Scottish academics led by Professor David McCrone has been surveying social attitudes in Great Britain on a regular basis since 1992, asking the same questions about identity and nationality. Over 21 years a consistent picture has emerged: three in four Scots consider themselves Scottish rather than British. Roughly the same striking result emerges from a more probing five-option question:

Which of these best describes how you see yourself?

Scottish not British; more Scottish than British; equally Scottish and British; more British than Scottish; British not Scottish.

Figure 22 shows responses to that question from all the nations of the UK and further afield. The results are stunning. People living in Scotland are seven times more likely to feel ‘more Scottish than British’ than the other way round. The ratio in Wales is just two to one and in England identification is almost equal, with half explicitly stating their identity is equally English and British.10

David McCrone also compared Scottish identity with two other stateless nations and found national identity in Scotland markedly stronger than in French-speaking Quebec or amongst Catalans – even though 70 per cent of Catalans back independence from Spain.

How can we account for these striking differences? Anthony Barnett says:

If you ask a Scot or a Welsh person about their Britishness, the question makes sense to them. They might say that they feel Scots first and British second. Or that they enjoy a dual identity as Welsh-British, with both parts being equal. Or they might say ‘I’m definitely British first’. What they have in common is an understanding that there is a space between their nation and Britain, and they can assess the relationship between the two. The English, however, are more often baffled when asked how they relate their Englishness and Britishness to each other. They often fail to understand how the two can be contrasted at all. Englishness and Britishness seem inseparable – like two sides of a coin, neither term has an independent existence from the other.11

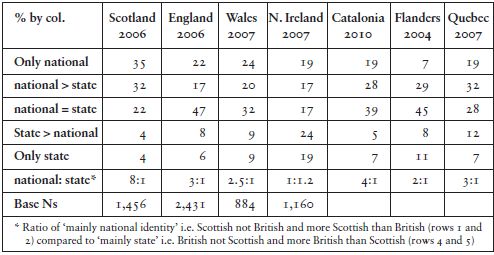

This muddle may be acceptable in England – it’s maddening in Scotland and only serves to accentuate the Scots perceptions of their national identity. Indeed since Mrs Thatcher and the abortive devolution referendum of 1979, Scottish feelings of solidarity towards other Scots have even transcended class differences as Figure 23 demonstrates.

Figure 23: Who do you identify with most?

A similar survey of identity in England (2006) found respondents fairly evenly spread between those who identify most with the same class in Scotland (23 per cent), the opposite class in England (29 per cent) and no preference (21 per cent).

So Scottishness is more powerful than any other national or class identity – in contrast to every other part of the UK. The Scots feel extremely Scottish and yet a clear majority in every opinion poll wants to stay within Britain instead of opting for independence.

What should we make of that conundrum?

Until recently, key writers viewed the Scots dual identity as a source of confusion and weakness:

Scottish culture is characterised as split, divided, deformed. This is a not unfamiliar view of Scottish culture, epitomised by Walter Scott, that Scotland is divided between the ‘heart’ (representing the past, romance, ‘civil society’) and the ‘head’ (the present and future, reason, and, by dint of that, the British state).12

And yet across the world, nation-states – where head and heart combine – are the exception not the rule. Some degree of ambiguity in state/national identity is as normal as bi or tri-lingualism beyond our monoglot shores. In accepting and understanding this ambiguity, Scots are surprisingly modern.

As Cairns Craig points out:

The fragmentation and division which made Scotland seem abnormal to an earlier part of the 20th century came to be the norm for much of the world’s population. Bilingualism, biculturalism and the inheritance of a diversity of fragmented traditions were to be the source of creativity rather than its inhibition in the second half of the 20th century, and Scotland ceased to have to measure itself against the false ‘norm’, psychological as well as cultural, of the unified national tradition.13

This then, is the danger for the continuing Union. Britishness is a fairly unlovely cultural construct, just as Esperanto is a fairly unloved constructed language. It’s nobody’s top preference – but at least Esperanto is fair. Everyone must learn and hardly anyone has the undue advantage of being born a ‘native speaker.’ Britishness is different. It isn’t neutral and it isn’t fair. If there was was a carefully selected ‘UK Greatest Hits’ Robert Burns would surely be in the Top Ten and his poetry taught in every British school, as it has been for some time in Russia. Instead, modern Britishness largely equals cultural Englishness and the preoccupations of the m25 cast widely across the whole UK. And Burns’ 250th anniversary in 2009 went unmarked on network British TV and radio while Dickens’ 200th anniversary merited an entire season. Was Burns not British?

The lazy conflation of the English nation and the British State will increasingly and disproportionately irk the Scots because we disproportionately notice and understand the difference. But a nation of five million cannot force 55 million neighbours to show sustained interest in our distinctive cultural jewels – unless they become world famous like Andy Murray. Thus Scotland is constantly being ‘rediscovered’ by English TV presenters, gob-smacked and pleasantly surprised by the difference of the country they have been sent to explore – a valid reaction for coverage by a ‘foreign’ TV channel but hardly cricket for the British Broadcasting Corporation whose staff are meant to show some familiarity with all of these islands – not just the bit around London.

If ‘British’ culture was carefully composed of the best offerings from all four nations – a bit like the British Lions rugby squad – all UK citizens would know something of Britain’s physical and cultural diversity and Burns’ 250th anniversary would have had its moment in the sun. But that didn’t happen because British culture isn’t a distinct and consciously crafted umbrella fusing together the best of English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish cultures. It’s often a tired, redundant restatement of Victorian Empire values concealed most of the time, like a shrivelled Wizard of Oz, behind the enormous bulk of its more energetic English proxy.

It could have been different.

A British state based on parity, equality and mutual respect might have consciously created a synthetic Britishness based on the best work of all its constituent parts. The model was there in the heady (almost) devolutionary days of the ’70s when Nationwide dominated peak-time viewing on BBC TV – a nightly news magazine programme (the equivalent of BBC1’s The One Show) which brought reports from every part of the UK to everyone else. It featured a mixture of accents, stories and pre-occupations from all over the UK and exposed all viewers to that same mixture every night. Presumably Nationwide was anchored from London, but its feel was decidedly non-metropolitan. Look North, Reporting Scotland, Scene around Six and Points West all registered in my young mind along with their spectacular backdrops, accents and memorably flamboyant presenters. Today those ‘regional’ programmes still exist – but broadcast only to themselves.

In the 1970s when Tory Ted Heath seemed to smile on the prospects of Scottish devolution, Britain’s diversity was a cause for celebration, not eye-rolling exasperation. The Home Internationals allowed national football and rugby teams to establish surrogate pecking orders, and entertainment programmes like It’s a Knockout pitted towns from all over Britain against one another every Saturday night. And then it all stopped.

The centralising English nationalist Margaret Thatcher won the election of 1979 – hot on the heels of the Scottish referendum debacle. Maggie’s dismissive approach to a shared model of Britishness put an end to what conceivably might have become a more federal country. Instead, a ‘winner takes all’ Britain emerged, meaning England’s sheer size would allow its values to trump all others for decades.

And that may have terminally unravelled Britishness.

According to David McCrone, the British state was built upon the three pillars of Protestantism, Imperialism and Unionism. After 1945 they each began to crumble:

Growing secularisation, but above all, the moral economy of the welfare state, transformed people’s dependence on the Church. Demobilisation and the end of empire released the need for a standing army, and a military attachment to the state. Finally political Unionism lost its appeal to Scotland’s middle classes, while there was less reason for workers to be thirled to the Conservative Party.14

In short the British State was crumbling before Maggie applied the tin lid by destroying the shared version of Britishness and the shared ownership of national resources Scots so earnestly supported. When she sold off Britain-wide institutions like British Rail, British Steel, the British Coal Board and British Gas and introduced privatisation to education and health, Mrs T shattered emotional ties and scuppered the post war deal that bound social democratic Scots to the British state. National, cultural identity was already cheerfully Scottish. With devolution state identity would become Scottish too. Since the days of Margaret Thatcher, Scots have been going through a slow process of disengagement – a bit like departing members of the Labour Party who once proclaimed ‘we didn’t leave the party, the party left us’.

It’s ironic. The Scots’ steadfast belief in a comprehensive Nordic style welfare state means we have become keepers of the flame – perhaps the only remaining ‘true’ believers in a British post war settlement which saw the Englishman Clement Atlee and the Welshman Aneurin Bevan deliver a welfare state conceived by the Scotsman Keir Hardie. That ‘Best of British’ joint settlement is ebbing away with each rightward lurch south of the border, each new privatisation of the English state and each victory by the Europhobic UKIP.

David Marquand once concluded: ‘Shorn of empire, “Britain” had no meaning.’15

Perhaps though, shorn of Empire, the ‘old’ concept of Britishness simply changed to mean something else.

Immigrants from former colonies arrived to work and have changed England’s population profile and ethnic mix, prompting a new and urgent debate about Britishness centred on multi-culturalism. This debate about ethnic Britishness preoccupies England more than Scotland, where the ethnic population is ten to 15 times smaller. Effectively, in their conception of Britishness, the English have moved on.

So we have two partners in a territorial union established to run the shared machinery of a state, each updating their own versions of its shared culture.

The Scots are reassessing Britishness; by which we mean the Union with England.

The English are also reassessing Britishness; by which they mean the ethnic, multicultural challenge facing largely themselves.16 We are talking at cross purposes except for those moments where the Scots force the old Union agenda on English partners who’ve otherwise forgotten the rules of the game (and lost the board).

Every day in almost every aspect of life, two sets of values are grinding away at each other – but only in Scotland. Like the juddering movements of two tectonic plates they disrupt business as usual, create low level anxiety about the future, demand attention and consume energy.

But why only here?

Because here two distinct and powerful cultural traditions collide. On the one hand, Britishness is physically embodied in Scottish streetscapes, civic loyalties and ‘National’ cultural traditions. On the other, the enduring strength of Scottish institutions has given us Scots law, the Church of Scotland, Scottish Highers, the four year Scots degree and the tenement, as well as negative features like the ‘Scottish Effect’ in health. All have combined over centuries to create a backbone, a set of expectations, a quasi-state complete with its own ‘Scottish way of doing things’ – for better and for worse. And it is this tangible, institutionally supported and authentic Scottish culture that pinches every day it’s forced into the increasingly ill-fitting shoe of Britishness.

Scots have also made themselves politically distinctive – not just through a devolved parliament with a proportional form of voting but also by developing a Nordic style social democratic cluster of parties instead of the Labour and Tory ‘Old Firm’ that still alternates in England. This also produces a distinctive ‘Scottish way of doing things’ – a polarising national lens through which all other key political debates about the workplace, health and international relations are viewed.

Still, who can blame English folk for using British interchangeably? In population terms, eight times out of ten they are right.17 Women have been similarly airbrushed from grammar, culture and history across the planet despite outnumbering men. Thirty-four million Canadians are regularly called Americans and 4.4 million Kiwis are confused every day with Australians. But nations that are also states can shrug it off. After all, they can reinflate squashed national identity with usefully tangible symbols: passports, flags and national anthems. Scotland cannot.

But every small nation in bed with an elephant, as Ludovic Kennedy once described England, experiences a degree of disturbed sleep. There are ways for a small partner to avoid being crushed and Scotland has tried all of them.

First, we have defended the elephant’s ‘right to roam’ in the hope that currying favour or understanding the psyche of the bed’s dominant force might improve the situation.

Second, we have tried to wake the elephant, electorally-speaking, for decades but no-one’s noticed.

Third, we have tried ear plugs but it’s hard not to be on the receiving end of London and British culture when BBC programmes and the most popular papers are largely produced south of the border.

Fourth, we have slunk off quietly to the spare room. But now we wonder why we should settle for permanent second best in a house partly financed by our oil income.

So finally, we are thinking of moving out. Such dramatic action, of course, runs counter to the other way Scots have survived within the UK – by learning to play it safe. By becoming bi-cultural, learning quickly to see ourselves as significant ithers see us and learning to jettison – or experience only in private – what isn’t easily understood. You could call that the Scottish cringe, or a clever ‘clandestine operation’ or a cultural insurance policy with a fairly hefty premium. You could say that fluency in a second culture is as useful as fluency in a second language. Or you could say that therein lies madness – or at least the road to decline. In fact you could say Scotland’s cultural dilemma arises from an inability to know which culture and whose cultural values we are meant to uphold, explore, learn about and value. Since no other part of the United Kingdom feels the pressure of two competing value systems quite like the Scots, it’s possible that Britishness itself is most acutely experienced here, as an alien imposition Scots can neither shape nor control.

Real stories and cultures are playing second fiddle all over England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland thanks to that cuckoo in the nest – Britishness.

Now to be crystal clear, none of this rejects the contribution of our closest neighbours, the English. According to research, the English are Scotland’s largest ethnic minority (eight per cent of the population and 12 per cent if you count spouses) and the most successfully integrated. Unlike other minorities, the English don’t live in all-English neighbourhoods and don’t create St George’s societies or sing ‘Land of Hope and Glory’. Some send their children to private schools, but the vast majority send their children to local schools with local Scots. If they are church-goers they attend Scottish churches (there’s even evidence that Episcopalians switch to the Kirk to fit in better).18 And according to author Murray Watson in Being English in Scotland, the majority of English incomers – contrary to the stereotype – are not posh southerners, but working-class northerners. Indeed, English incomers have sometimes fought battles local Scots have hesitated to tackle. Dave Morris, the outspoken head of the Ramblers Association in Scotland, arrived in Aviemore from Wolverhampton 30 years ago:

Back then, local people were being told how to vote by the laird. A fear of offending helped silence local dissent. It also explained why incomers were viewed as useful and potentially trouble-making at the same time – they weren’t bound by the same local ‘rules’.

Long-term English residents in Scotland are often aghast at the lack of support given to uniquely special bits of Scottish culture. The problem in Scotland is not ‘Englishness’, but the vast amount of cultural space given over to a relatively hollow, uninspiring and redundant Britishness which offends against the Scots belief in the vigorous union that created the welfare state and the Scottish way of doing things, bolstered during recent centuries by our independent institutions and by our resurgent and diverse Scottish cultures.

If the vain attempt to marshal all diversity on these islands into one dominant narrative could finally be abandoned, each nation could plough the lion’s share of its cultural cash first, foremost and unapologetically into its own culture(s) and its own understanding of world culture, in which the others may or may not play a part. Who knows, one day – if a heartfelt parity of esteem returns – a genuinely shared British culture may emerge.

In the meantime though, Scotland must re-order its priorities.

The problem is not the hardy English perennial – it’s the shade-creating, soil-adapting and overgrown shrub called Britishness.

It’s time for selective weeding in the interests of balance and support for home-grown species.

The hollyhocks will keep growing further south.

The little white rose of Scotland cannot.

—

1 D. Green, ed. Cobbett’s Tour in Scotland (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1984).

2 The Act of Proscription 1747 says: ‘No man or boy, within that part of Great Briton called Scotland, other than shall be employed as officers and soldiers in his Majesty’s forces, shall on any pretence whatsoever, wear or put on the clothes commonly called Highland Clothes (that is to say) the plaid, philibeg, or little kilt, trowse, shoulder belts, or any part whatsoever of what peculiarly belongs to the highland garb; and that no tartan.’ Carrying weapons had already been banned in the Disarming Act of 1716.

3 J.G. Gibson, Traditional Gaelic Bagpiping 1745–1845 (Montreal: McGill Queen’s Press, 2000).

4 MacLean C. The Highlands, Mainstream Edinburgh 2006.

5 T. Pattison, Selection from the Gaelic Bards, Edinburgh 1866.

6 M. Castells, The Power of Identity, (Blackwells, 1997).

7 M. Gardiner, Modern Scottish Culture, (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2005).

8 D. McCrone, Understanding Scotland, (Routledge, 2001).

11 A. Barnett, Our Constitutional Revolution (London: Vintage, 1997).

13 C. Craig, History of Scottish Literature (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1990).

14 D. McCrone, Understanding Scotland (Routledge, 2001).

15 D. Marquand, How united is the modern United Kingdom (London: Routledge, 1995).

16 Now this is not to say the multicultural debate about Britishness is un-important to Scots. Far from it. The bananas thrown at black Rangers footballer Mark Walters were testimony to that. So too the murder of Firsat Dag, a Turkish asylum seeker stabbed to death in Glasgow in 2001. In 2006, three members of a Glasgow Asian gang were jailed for life for the racially motivated murder of white schoolboy, Kriss Donald and today the killers of Surjit Singh Chhokar – stabbed to death 15 years ago – have still to be brought to justice. Ethnicity and racism matter – but the size of Scotland’s minority ethnic population was just two per cent in 2001 compared with 29 per cent per cent in Greater London and 20 per cent in the West Midlands Metropolitan area. That’s a big difference. Historically there have been lower levels of immigration north of the border and a Scottish cross-party consensus arguing for more incomers to boost Scotland’s flagging population. The British National Party has failed to win a single seat north of the border or save a single election deposit. Likewise the more moderate UKIP.

17 The English population of 53.01 million in 2011 was 83.6% of the UK population of 62.74 million.

18 Bill Miller and Asifa Hussain in Multicultural Nationalism: Islamophobia, Anglophobia and Devolution, OUP, 2006.