LESSON 5

Because It’s for Business

これはビジネスだから

Kore wa Bijinesu Dakara

In this lesson, you will learn words and phrases useful in a business context in Japan. You will also learn a variety of clauses that can be used as a modifier for a noun or a modifier for the main sentence.

|

[cue 05-1] |

Basic Sentences

1. |

あそこに立っている人はパートの山本さんです。 Asoko ni tatte iru hito wa pāto no Yamamoto-san desu. The person who is standing over there is Ms. Yamamoto, a part-time employee. |

|

2. |

昨日ここへ来たのはだれですか。 Kinō koko e kita no wa dare desu ka. Who is the one who came here yesterday? |

|

3. |

コストの高いハードウエアは作れません。 Kosuto no takai hādouea wa tsukuremasen. We cannot manufacture high-cost hardware. |

|

4. |

エクセルを使うのが上手な人を探しています。 Ekuseru o tsukau no ga jōzu na hito o sagashite imasu. I’m looking for someone who is skilled at using Excel. |

|

5. |

英語のできる社員は3人います。 Eigo no dekiru shain wa san-nin imasu. We have three employees who can speak English. |

|

6. |

「あの人は知っていますか。」 “Ano hito wa shitte imasu ka.” “Do you know that person?” |

「ちょっと分かりません。」 “Chotto wakarimasen.” “I don’t know her.” |

7. |

あそこの会社の株は高くなるでしょう。 Asoko no kaisha no kabu wa takaku naru deshō. The stock value of that company will probably go up. |

|

8. |

円高なのでアメリカで買った方がいいですよ。 Endaka na no de Amerika de katta hō ga ii desu yo. The (Japanese) yen is strong, so it’s better to buy it in the U.S. |

|

9. |

病気なのに出勤するんですか。 Byōki na no ni shukkin suru n desu ka. Are you going to work although you are sick? |

|

10. |

店で売らないでネットで売るんですか。 Mise de uranai de netto de uru n desu ka. Instead of selling them at the store, are we selling them online? |

|

11. |

朝ごはんを食べないで出勤するんですか。 Asa go-han o tabenai de shukkin suru n desu ka. Are you going to go to work without eating breakfast? |

|

12. |

確認せずにメールを送ってしまいました。 Kakunin sezu ni mēru o okutte shimaimashita. I sent the email without checking it. |

|

13. |

ブラウンさんは午後1時に成田に着くはずです。 Buraun-san wa gogo ichi-ji ni Narita ni tsuku hazu desu. Mr. Brown is supposed to arrive at Narita at 1 p.m. |

|

14. |

外国語は若いうちに習った方がいいですよ。 Gaikokugo wa wakai uchi ni naratta hō ga ii desu yo. It’s better to learn a foreign language while you are young. |

|

15. |

この会社に勤める前は何をしていましたか。 Kono kaisha ni tsutomeru mae wa nani o shite imashita ka. What were you doing before you started to work for this company? |

|

16. |

「仕事が終わった後でちょっといいですか。」 “Shigoto ga owatta ato de chotto ii desu ka.” “Do you have a minute after you are done with your work?” |

「ええ。今終わったところです。」 “Ē. Ima owatta tokoro desu.” “Sure. I’ve just finished.” |

17. |

昨日は遅くまで仕事をしました。 Kinō wa osoku made shigoto o shimashita. I worked until late yesterday. |

|

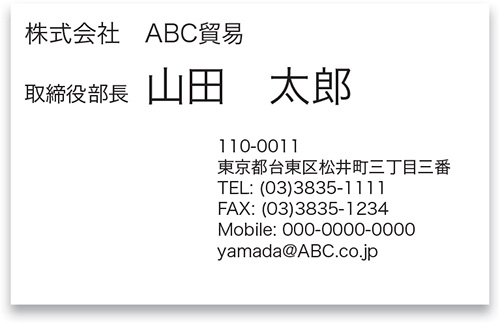

CULTURE NOTE Meishi (Business Cards)

Japanese business people and professionals almost always exchange their business cards when they introduce themselves. A Japanese business card, called meishi in Japanese, can be either horizontal or vertical and includes one’s affiliation, title, and contact information. It is very important to handle a business card very respectfully when you exchange cards. When presenting your business card to someone, hand it over so that it faces him/her. When receiving a business card from someone, use both hands to accept it and bow slightly. Read the information on it carefully, and do not put it away right away. If you are sitting, leave it on the table in front of you while you are talking with the person.

|

[cue 05-2] |

Basic Vocabulary

BUSINESS INSTITUTIONS

会社 kaisha |

company, firm |

店 mise |

store |

事務所 jimusho |

office |

給料 kyūryō |

salary |

時給 jikyū |

hourly pay |

ボーナス bōnasu |

bonus |

PEOPLE

社員 shain |

staff, company, employee |

正社員 seishain |

full-time employee |

派遣社員 haken shain |

an employee sent from a temporary personnel service |

パート pāto |

part-time job (mostly for housewives) |

バイト baito |

part-time job (mostly for students and young people) |

OL ōeru |

female office workers (office lady) |

上司 jōshi |

boss |

マネージャー manējā |

manager |

アシスタント ashisutanto |

assistant |

社長 shachō |

company president |

秘書 hisho |

secretary |

FUNCTIONS

会計士 kaikeishi |

accountant |

プログラマー puroguramā |

programmer |

コンサルタント konsarutanto |

consultant |

アントレプレナー (起業家) antorepurenā (kigyōka) |

entrepreneur |

営業 eigyō |

sales |

生産 seisan |

production |

マーケティング māketingu |

marketing |

プロモーション puromōshon |

promotion |

広告 kōkoku |

advertisement |

輸出 yushutsu |

export |

輸入 yunyū |

import |

DOCUMENTS AND FILES

請求書 seikyūsho |

invoice |

領収書 ryōshūsho |

receipt |

パワーポイント pawāpointo |

Power Point |

エクセル ekuseru |

Excel |

書類 or 文書 shorui or bunsho |

document |

ファイル fairu |

file |

ACTIONS

いる・いります iru/irimasu |

is needed, wanted |

借りる・借ります kariru/karimasu |

borrows |

貸す・貸します kasu/kashimasu |

lends |

見つける・見つけます mitsukeru/mitsukemasu |

finds |

探す・探します sagasu/sagashimasu |

searches |

調べる・調べます shiraberu/shirabemasu |

checks up on |

使う・使います tsukau/tsukaimasu |

uses |

作る・作ります tsukuru/tsukurimasu |

makes, manufactures |

売る・売ります uru/urimasu |

sells |

忘れる・忘れます wasureru/wasuremasu |

forgets |

やめる・やめます yameru/yamemasu |

resigns, ceases it, gives up (doing something) |

雇う・雇います yatou/yatoimasu |

employs |

分析する・分析します bunseki suru/bunseki shimasu |

analyzes |

生産する・生産します seisan suru/seisan shimasu |

produces |

ADJECTIVES & ADJECTIVAL NOUNS

多い ōi |

is much, are many |

少ない sukunai |

is little, are few |

忙しい isogashii |

is busy |

暇(だ) hima (da) |

(is) free, not busy |

BUSINESS TRIP

新幹線 shinkansen |

bullet train |

ホテル hoteru |

hotel |

ビジネスホテル bijinesu hoteru |

business hotel |

カプセルホテル kapuseru hoteru |

capsule hotel |

POLITE PHRASES AT THE OFFICE

いつもお世話になっております。 Itsu mo o-sewa ni natte orimasu. |

Thank you for your kindness always./Thank you for your continued patronage. |

外出中でございます。 Gaishutsu-chū de gozaimasu. |

(He) is out now. |

会議中でございます。 Kaigi-chū de gozaimasu. |

(He) is at the meeting now. |

電話中でございます。 Denwa-chū de gozaimasu. |

(He) is on the phone now. |

宜しくお願いいたします。 Yoroshiku o-negai itashimasu. |

Thank you in advance. (lit., Please take care of my matter favorably.) |

お先に。 O-saki ni. |

Sorry, but I have to get going. Bye. (lit., Ahead.) |

お疲れ様。 O-tsukare-sama. |

Thank you for your work./Good work today. (lit., Your tiredness.) |

ご苦労様。 Go-kurō-sama. |

Thank you for your work. (lit., Your efforts.) |

Structure Notes

5.1. Modifiers

In English one noun can modify (restrict the meaning) of another noun just by standing next to it: ‘Business Action Plan Objective; Supply Closet Restocking List.’ In Japanese, when one noun modifies another, the two are usually connected by the particle no. In the case of book titles or names of organizations and institutions, frequently several nouns may be combined to make a COMPOUND NOUN:

基本日本語文法

Kihon-Nihongo-Bunpō

Basic Japanese Language Grammar

日本貿易株式会社

Nippon-Bōeki-Kabushiki-Gaisha

The Japan Trade Co., Inc.

But these are special cases. Ordinarily, modifying nouns are followed by no:

日本語の辞書 Nihongo no jisho

a Japanese (language) dictionary

アメリカのビジネスマン America no bijinesuman

an American businessman

昨日の会議 kinō no kaigi

yesterday’s meeting

私のパソコン watashi no pasokon

my PC

大阪の工場 Ōsaka no kōjō

the Osaka factory; factories in Osaka

The last noun is often dropped if it is not a person and is understood in the context, as below:

これは日本語の辞書です。あれは中国語のです。

Kore wa Nihongo no jisho desu. Are wa Chūgokugo no desu.

This is a Japanese dictionary. That one is a Chinese one.

Now, in English when a verb or verb phrase modifies a noun, it FOLLOWS the noun and is introduced by a word like who, which, that, and when, as in ‘the man who came yesterday; the book, which is on the table; the movie that I saw; that time when we were in Osaka.’ Notice that sometimes the introductory word may be omitted in English: ‘the movie I saw, that time we went to Osaka.’ Japanese verbs and verb phrases “precede” the noun they modify and have no introductory word or linking particle:

昨日ここへ来た人

kinō koko e kita hito

the person who came here yesterday

机の上にある書類

tsukue no ue ni aru shorui

the documents that are on the desk

去年行ったところ

kyonen itta tokoro

the place I went last year

大阪にいた時

Ōsaka ni ita toki

the time we were in Osaka

You have already had expressions like:

行くつもり iku tsumori

intention of going

すること suru koto

the fact of doing (something) (the act of doing something; doing something)

行ったこと itta koto

the fact of having gone (the occasion for me to be there)

These are examples of modifier expressions.

The modifying expression preceding a noun phrase may be very short, or it may be quite long. It will always make a complete sentence by itself except that the predicate part is in the plain form, and you would want to change this to the polite form to use as a complete sentence. Notice that the meaning of the juxtaposition between the modifying verb and the noun may be either that of a “subject” or an “object” relationship:

見た人 mita hito

the person who saw (it)

見た人 mita hito

the person whom (someone) saw

The relationship is usually made clear by the particles in the rest of the clause:

その映画を見た人 sono eiga o mita hito

the person who saw that movie

私が見た人 watakushi ga mita hito

the person I saw

The subject of a modifying clause is never followed by wa—that would make it the topic for the entire sentence, not just the modifying clause. It is marked either by ga (emphatic) or by no (non-emphatic). If you like, you may think of no as replacing the particle wa in modifying clauses:

あの人はその映画を見ました。

Ano hito wa sono eiga o mimashita.

He saw THAT MOVIE.

あの人の見た映画はそれです。

Ano hito no mita eiga wa sore desu.

THE MOVIE (that) he saw is that one.

あの人がその映画を見ました。

Ano hito ga sono ega omimashita.

HE saw that movie.

あの人が見た映画はそれです。

Ano hito ga mita eiga wa sore desu.

The movie (that) HE saw is that one.

In other words, only sentences have topics; clauses have subjects (or objects). The particle used for the non-emphatic subject of a clause is no; the particle used for the emphatic subject is ga. If the modifying clause is quite long and the subject is separated from the verb by a number of words, the emphatic subject particle ga is usually used.

私の行ったゴルフ場は安いところです。

Watashi no itta gorufujō wa yasui tokoro desu.

The golf course I went to is an inexpensive place.

私が加藤部長と先週行ったゴルフ場は結構よかったです。

Watashi ga Katō buchō to senshū itta gorufujō wa kekkō yokatta desu.

The golf course where I went last week with Mr. Kato, the division manager, was quite good.

When you hear long modifier clauses in actual conversation, you may be confused as to the breaking point where the modifier stops and the part modified begins. Listen for the “plain” imperfect and perfect forms, forms like suru, shita; iku, itta; kuru, kita; taberu, tabeta: unless followed by a particle like keredomo or kara, they probably modify the word or phrase that follows. At the breaking point, stick in a ‘which,’ and then make mental switch of the two parts around to the usual English order. This is just a first-aid measure, of course. After you get used to modifier clauses, you will be putting them in quite naturally like a Japanese person, without worrying about the fact that in English you would reverse the order. Remember: everything up to the breaking point modifies the following noun expression. Notice the breaking points (indicated by a forward slash) in the following examples. But try to avoid pausing: the BREAKING POINT is in your head, not on your tongue.

データ入力とプログラミングのできる/方を募集しています。

Dēta nyūryoku to puroguramingu no dekiru/kata o boshū shite imasu.

We are looking for someone who can do data inputting and programming.

料理になれていない人が作った/食べ物はあまり食べたくない。

Ryōri ni narete inai hito ga tsukutta/tabemono wa amari tabetaku nai.

I don’t want to eat dishes prepared by someone who is not used to cooking.

5.2. Modifier clauses made with adjectives

Recall that the full meaning of real adjectives in Japanese is not just ‘good, bad, white, red’ and the like but ‘IS good, IS bad, IS white, IS red’ etc.:

いいから ii kara

because it’s good

悪かったけれども warukatta keredomo

it was bad, but

白くていいから shirokute ii kara

it’s nice and white, so…

Just as verbs can have a subject in Japanese, so can adjectives. And in modifier clauses, the particle that follows the subject is either ga (emphatic) or no (non-emphatic):

天候が悪いところ

tenkō ga warui tokoro

a place where the WEATHER’S bad

天候の悪いところ

tenkō no warui tokoro

a place where the weather’s BAD

Here are some additional examples of adjectives in sentences:

プログラミングの経験のない人は採用しません。

Puroguramingu no keiken no nai hito wa saiyō shimasen.

We are not going to hire people who do not have programming experience.

店は人の多いところにある方がいいです。

Mise wa hito no ōi tokoro ni aru hō ga ii desu.

As for stores, it’s better for them to be in a location (that is) heavily trafficked.

カプセル・ホテルは会社が多くて, 駅に近いところに沢山あります。

Kapuseru hoteru wa kaisha ga ōkute, eki ni chikai tokoro ni takusan arimasu.

Capsule hotels are located where there are lots of companies and close to a train station.

5.3. Modifier clauses made with a copula

Something special happens when a copula clause, like sakka desu ‘he is a writer,’ is used as a modifier clause. To mean ‘my friend, who is a writer,’ they do not say sakka da tomodachi but sakka no tomodachi. Now, this no is not the particle that shows that one noun modifies another—it isn’t ‘a writer’s friend,’ it is ‘my friend, WHO IS a writer.’ This no is a special form of the copula, an alternant, or the alternate form, of the word da that occurs whenever a copular clause is put in the modifier position before a noun phrase. You can see the difference between the particle no and the copula-alternant no (= da) here:

作家の友達 sakka no tomodachi

the writer’s friend

作家の友達 sakka no tomodachi

the friend WHO IS a writer

Since the two expressions sound just alike, you have to tell from the context or situation which no it is you are hearing. Most of the time, there is little doubt. Here are additional examples:

母親が60歳以上の学生は全体の30%だった。

Hahaoya ga rokujus-sai ijō no gakusei wa zentai no sanjup-pāsento datta.

The students whose mothers are over sixty years old constituted 30 percent of entire student body.

うちの会社には出身が九州の男性が3人いる。

Uchi no kaisha ni wa shusshin ga Kyūshū no dansei ga san-nin iru.

There are three men whose birthplace is Kyushu in our company.

5.4. Modifier clauses made with adjectival nouns

In the previous section, you have seen that no is an alternant of da. However, no is not the only alternant of da. There is also an alternant na that occurs after adjectival nouns. Adjectival nouns are a special sort of nouns that do not often occur before particles like wa, ga, o but occur before some form of the copula (desu, da, na) or before the particle ni. When these adjectival noun clauses, like kirei desu ‘is pretty,’ occur in modifier position, the expected form da occurs in the alternant form of na as in:

きれいな女の人

kirei na onna no hito

women WHO ARE pretty, or pretty women

In citing nouns it is convenient to note the ones that are adjectival nouns by adding in parentheses (na). Here are some common ones:

バカ(な) baka (na)

fool, foolish

丈夫(な) jōbu (na)

strong, rough

きれい(な) kirei (na)

pretty, neat, clean

失礼(な) shitsurei (na)

rude

丁寧(な) teinei (na)

polite

好き(な) suki (na)

liked, likable

大好き(な) daisuki (na)

greatly liked

大変(な) taihen (na)

terrific, terrible, quite a…

嫌い(な) kirai (na)

disliked, dislikable

大嫌い(な) daikirai (na)

greatly disliked

素敵(な) suteki (na)

excellent, swell

楽(な) raku (na)

comfortable

立派(な) rippa (na)

splendid, elegant

静か(な) shizuka (na)

quiet

結構(な) kekkō (na)

excellent, satisfactory

元気(な) genki (na)

healthy, good-spirited

上手(な) jōzu (na)

skillful, good at

便利(な) benri (na)

convenient

下手(な) heta (na)

unskillful, poor at

不便(な) fuben (na)

inconvenient

有名(な) yūmei (na)

famous, well-known

嫌(な) iya (na)

unpleasant

にぎやか(な) nigiyaka (na)

lively, bustling, gay

変(な) hen (na)

queer, odd

大丈夫(な) daijōbu (na)

safe

Most nouns belong to the ordinary class that have no for the copula alternant (byōki no hito, puroguramā no Tanaka-san). Some nouns belong to either class: ordinary no or adjectival nouns. An example is iroiro: you can say either iroiro no or iroiro na (commonly pronounced iron-na) to mean ‘various, of various sorts’:

色々の形 iroiro no katachi

a variety of shapes

色々な形 iroiro na katachi

a variety of shapes

There are a few adjectives that may have na instead of the ending i when placed before a noun.

小さい部屋 or 小さな部屋

chīsai heya or chīsa na heya

a small room

大きい船 or 大きな船

ōkii fune or ōki na fune

a big ship

When you have two adjectival nouns modifying the same noun phrase, the first takes the gerund of the copula de ‘is and’: shizuka de kirei na tokoro ‘a place that is quiet and (is) pretty.’

Here are some examples of adjectival nouns in sentences:

大変なことをしてしまいました。

Taihen na koto o shite shimaimashita.

He did something terrible.

この仕事は大変ですよ。

Kono shigoto wa taihen desu yo.

This job is tough.

パソコン操作が得意な人は有利です。

Pasokon sōsa ga tokui na hito wa yūri desu.

Those who are good at using computers will have some advantage.

きれいでやさしい人は好かれます。

Kirei de yasashii hito wa sukaremasu.

Those who are pretty and kind are liked by others.

働くのが嫌いな人は雇いません。

Hataraku no ga kirai na hito wa yatoimasen.

We will not hire those who do not like to work.

Before the verb naru ‘becomes,’ the particle ni occurs just as after any other noun:

病気になりました。

Byōki ni narimashita.

He got sick.

元気になりました。

Genki ni narimashita.

He got his health back.

With other verbs, the particle ni makes the meaning of the adjectival noun ‘in such a manner’:

静かにしてください。

Shizuka ni shite kudasai.

Please be quiet (behave in a quiet way).

毎日元気にしています。

Mainichi genki ni shite imasu.

I’m in good spirits every day (behave in a good-spirited manner).

あの人は英語を上手に話しますね。

Ano hito wa Eigo o jōzu ni hanashimasu ne.

That person speaks English well.

5.5. The noun の no

You have seen two kinds of no: the particle and the copula-alternant. There is yet a third kind of no that is a noun. This noun has two somewhat different meanings, ‘one WHO’ and ‘fact THAT.’ In some expressions this word is used much like hito ‘person’:

あそこに座っているのはだれですか。

(or あそこに座っている人はだれですか。)

Asoko ni suwatte iru no wa dare desu ka.

(or Asoko ni suwatte iru hito wa dare desu ka.)

Who is the person who is sitting over there?

In some expressions, the noun no is used like koto ‘fact’:

アメリカの映画を見るのが好きです。

(or アメリカの映画を見ることが好きです。)

Amerika no eiga o miru no ga suki desu.

(or Amerika no eiga o miru koto ga suki desu.)

I like to see American movies.

5.6. …の (ん)です …no (n) desu

The noun no followed by the copula makes a special expression meaning ‘it is a fact that…,’ but it is not easily translated in English. This is a very common formula in Japanese: it may be tacked on at the end of any sentence (with the verb, adjective, or copula in either plain imperfect or plain perfect), giving an additional refinement. When no desu is pronounced softly with a contraction, as in n desu, it somewhat softens the directness of the statement, elicits the listener’s response and makes the dialog more interactive.

「実は来月結婚するんです。」

“Jitsu wa raigetsu kekkon suru n desu.”

“Umm, I’m getting married next month.”

「え,だれとですか。」

“E, dare to desu ka.”

“What? To whom?”

N(o) desu is somewhat more common when the sentence is not completed but left dangling with a particle like kedo… (ga…) ‘but…’ or kara… ‘so….’

「あのう,ここでタバコはこまるんですけど。」

“Anō, koko de tabako wa komaru n desu kedo.”

“Umm, smoking here is a bit of problem, but….”

「ああ,すみません。」

“Ā, sumimasen.”

“Oh, sorry.”

「ちょっとお願いがあるんですが。」

“Chotto onegai ga aru n desu ga.”

“I have a favor to ask, but…”

「何ですか。」

“Nan desu ka.”

“What is it?”

If uttered with a firm intonation, with or without the contraction, no desu makes the expression somewhat more formal.

「毎日3時間は練習するのです。いいですね。」

“Mainichi san-jikan wa renshū suru no desu.”

“You must practice (at least) for three hours every day. ”

「はい。」

“Hai.”

“Yes.”

「そんなことどこに書いてあるのですか。」

“Sonna koto doko ni kaite aru no desu ka.”

“Such a thing, where is it written?”

「ええと。」

“Ēto.”

“Well…”

Notice the use of the copula forms datta and na (= da). Before the noun no, the plain imperfect copula appears in the form na regardless of whether preceded by an ordinary noun or an adjectival noun:

前はパートだったんですが,今は正社員なんです。

Mae wa pāto datta n desu ga, ima wa seishain na n desu.

I was a part-time worker but am a full-time employee now.

父はデパートの地下が好きなんです。

Chichi wa depāto no chika ga suki na n desu.

My father loves the basement of a department store.

5.7. Verb + でしょう deshō

Many people go a step further and drop the no completely from the expressions discussed above: Doko e iku desu ka? ‘Where’s he going?,’ Otearai ni itta desu ‘He went to the men’s room.’ As a general thing, this usage is frowned upon by speakers of Standard Japanese and should perhaps be avoided by the student. However, certain forms that have become a part of Standard Japanese originated in this dropping of the no: the polite forms of the adjective atarashii desu, ii desu came from the forms atarashii no desu, ii no desu. Some older Japanese still consider it poor style to say atarashii desu, ii desu, preferring at least atarashii n desu, ii n desu—but most people use the forms without even the n constantly, so that they are now a part of Standard Japanese. This helps explain the existence of two polite forms for the perfect adjective at one point: ii deshita and yokatta desu. They come from the expressions ii no deshita ‘it was a fact that it is good’ and yokatta no desu ‘it is a fact that it was good.’ The latter type of phrase, yokatta desu, is the currently accepted form.

In a similar way, expressions consisting of imperfect or perfect adjectives plus no deshō ‘will probably be the fact that…; must be…’ created the now Standard forms ii deshō ‘it must be good’ (compare Tanaka-san deshō ‘It must be Mr. Tanaka’) and yokatta deshō ‘it must have been good’ (compare Tanaka-san datta no deshō ‘it must have been Mr. Tanaka’).

There already existed a polite tentative for verbs: ikimashō, hanashimashō, asobimashō. These polite tentatives once had the meaning ‘will probably do’ just as the polite copula deshō still has the meaning ‘will probably be.’ Sometimes the tentatives of verbs are still used with the ‘probably’ meaning. For example, in modern writings you will see arō (= aru darō), narō (= naru darō), dekiyō (= dekiru darō), ieyō (= ieru darō ‘probably can say’) and also tentative adjectives in -karō (= -i darō) such as yokarō (= ii darō) and nakarō (= nai darō).

For the meaning ‘probably,’ a plain form of the verb is used, either imperfect or perfect, depending on the meaning, followed by the tentative copula deshō (from no deshō ‘it’s probably a fact that’ with the no dropped). This is quite standard usage and often has the flavor of English ‘must (be), I bet that…, I’ll bet…,’ Sometimes kitto or tabun ‘no doubt, probably’ is added, often at the very beginning of the sentence, just to emphasize the probability. For example:

「これから株価が上がるでしょう。」

“Kore kara kabuka ga agaru deshō.”

“I guess the stock will go up from now on.”

「たぶんそうでしょう。」

“Tabun sō deshō.”

“It will probably do so.”

5.8. …かね …ka ne

The combination of the final particles ka and ne means something like ‘I wonder’ or ‘is it, do you think.’ It is often preceded by a tentative expression:

この企画は成功するでしょうかね。

Kono kikaku wa seikō suru deshō ka ne.

I wonder whether this project will be successful.

どうして失敗したんでしょうかね。

Dōshite shippai shita n deshō ka ne.

I wonder why it failed.

「たぶんエンジンが悪かったんでしょう。」

“Tabun enjin ga warukatta n deshō.”

“I guess the engine was bad.”

「そうでしょうかね。」

“Sō deshō ka ne.”

“I wonder whether it is the case.”

5.9. ので no de

The expression VERB (or ADJECTIVE or COPULA) + no de ‘it being a fact that; it is a fact that… and’ has a special meaning of ‘because’ or ‘since.’ This is similar to the meaning of kara. In most places no de and kara seem interchangeable, but there is a slight difference of meaning: no de emphasizes the “reason,” kara emphasizes the “result”:

去年は病気でたくさん仕事を休んだので,休暇をとることができませんでした。

Kyonen wa byōki de takusan shigoto o yasunda no de, kyūka o toru koto ga dekimasen deshita.

Because I took many days off due to sickness last year, I could not take vacation.

去年は病気でたくさん休んだから,休暇をとることができませんでした。

Kyonen wa byōki de takusan yasunda kara, kyūka o toru koto ga dekimasen deshita.

I took many days off due to sickness last year, so I could not take vacation.

As in the case of n(o) desu discussed in this lesson, the plain imperfect copula appears in the form na when followed by no de. Here are some additional examples:

私はパートなので週に3日しか働きません。

Watashi wa pāto na no de, shū ni mikka shika hatarakimasen.

Because I’m a part-time employee, I work only three days per week.

あの人はきれいなのでモデルにもなれるでしょう。

Ano hito wa kirei na no de moderu ni mo nareru deshō.

That person is pretty, so she can also be a model.

来月から働くのでスーツを買わなくてはいけません。

Raigetsu kara hataraku no de sūtsu o kawanakute wa ikemasen.

Because I’ll start working beginning next month, I need to buy a suit.

ここは禁煙なのでおタバコはご遠慮願います。

Koko wa kin’en na no de otabako wa goenryo negaimasu.

Because it is a non-smoking area, please refrain from smoking.

5.10. のに no ni

After a verb in the imperfect mood, the expression no ni, literally ‘to the fact that, at the fact that,’ has two different meanings: ‘in the process of doing, for the purpose of doing, in order to do’ and ‘in spite of the fact that…’ The two meanings are distinguished by context. Often the particle wa follows no ni in the first meaning, and the whole expression is frequently followed by a phrase indicating something is necessary (‘in the process of doing something’). Here are some examples of the first meaning ‘in the process of’:

日本語を勉強するのに(は)いい本が要ります。

Nihongo o benkyō suru no ni (wa) ii hon ga irimasu.

We need a good book in order to study Japanese.

アパートを借りるのに5万円かかります。

Apāto o kariru no ni goman-en kakarimasu.

To rent an apartment costs 50,000 yen.

Here are some examples of the second meaning ‘in spite of the fact that’:

勉強したのに,いい成績がもらえませんでした。

Benkyō shita no ni, ii seiseki ga moraemasen deshita.

Although I studied, I could not get a good grade.

まずいのに食べるんですか。

Mazui no ni taberu n desu ka.

Are you going to eat it even though it is not delicious?

As in the case of n(o) desu discussed in this lesson, the plain imperfect copula appears in the form na when followed by no ni:

まだ学生なのに高い車を乗り回しているんです。

Mada gakusei na no ni takai kuruma o nori-mawashite iru n desu.

Although he is still a student, he drives an expensive car.

どうして好きなのに好きだって言えないんですか。

Dōshite suki na no ni suki datte ienai n desu ka.

Why can’t you say you love her although you love her?

The first meaning of no ni ‘in the process of, for the purpose of, with the aim of’ is usually expressed by the noun tame ‘sake,’ which is often followed by ni and sometimes by wa or ni wa. The expression tame (ni) (wa) may be preceded by a plain imperfect verb form or by a NOUN + no:

日本語を勉強するためにはいい本が要ります。

Nihongo o benkyō suru tame ni wa ii hon ga irimasu.

We need a good book for studying Japanese.

日本語の勉強のためにいい本が要ります。

Nihongo no benkyō no tame ni ii hon ga irimasu.

We need a good book for the study of Japanese.

何のために大阪に行くんですか。

Nan no tame ni Ōsaka ni iku n desu ka.

Why are you going to Osaka?

The word tame is also used after a modifying phrase by many speakers as a virtual equivalent of kara ‘because’:

地震があったため電車が遅れた。

Jishin ga atta tame densha ga okureta.

The train was delayed due to an earthquake.

英語ができないため困りました。

Eigo ga dekinai tame komarimashita.

I had difficulties because I couldn’t speak English.

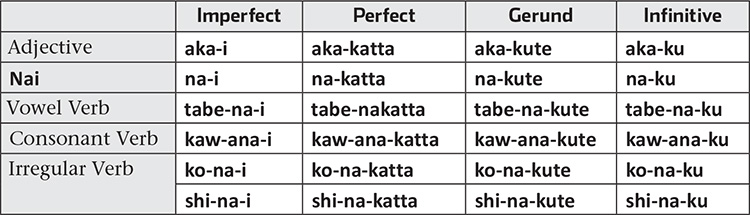

5.11. Plain negative …ない …nai

The polite negative ends in -masen for verbs, as in hanashimasen and ikimasen, and consists of a special construction for the copula ja arimasen, and for adjectives, infinitive (-ku) + arimasen.

The plain negative of ‘exists’ is a completely different word, the adjective nai ‘is non-existent.’ The plain negative of the copula is ja nai; of adjectives it is ku nai. And, in colloquial usage, (ja) nai desu is often used for (ja) arimasen, ku nai desu for ku arimasen. The plain negative of every other verb is an adjective made by adding the ending -(a)nai to the stem of the verb: add -anai to the consonant-ending stem; add -nai to the vowel-ending stem.

Meaning |

Plain Affirmative (Imperfect) |

Plain Negative (Imperfect) |

|

Vowel Verbs |

eats |

tabe-ru |

tabe-nai |

sees |

mi-ru |

mi-nai |

|

Consonant Verbs |

wins |

kats-u |

kat-anai |

rides |

nor-u |

nor-anai |

|

buys |

ka-u |

kaw-anai |

|

speaks |

hanas-u |

hanas-anai |

|

writes |

kak-u |

kak-anai |

|

swims |

oyog-u |

oyog-anai |

|

calls |

yob-u |

yob-anai |

|

reads |

yom-u |

yom-anai |

|

dies |

shin-u |

shin-anai |

|

Irregular Verbs |

comes |

ku-ru |

ko-nai |

does |

su-ru |

shi-nai |

Notice how the ‘disappearing’ w disappears in forms like kau but does not disappear in forms like kawanai. Also notice the ‘appearing’ s appears in forms like katsu but not in forms like katanai. Each of the negative verbs is conjugated like any other adjective—for example the adjective nai ‘is non-existent’ or akai ‘is red’:

あの製品はあまり売れなかったでしょう。

Ano seihin wa amari urenakatta deshō.

I guess that product did not sell very well.

父が帰って来なくて困っています。

Chichi ga kaette konakute komatte imasu.

I’m troubled because my father hasn’t come home.

部長は最近あまりしゃべらなくなりました。

Buchō wa saikin amari shaberanaku narimashita.

The division manager stopped speaking lately.

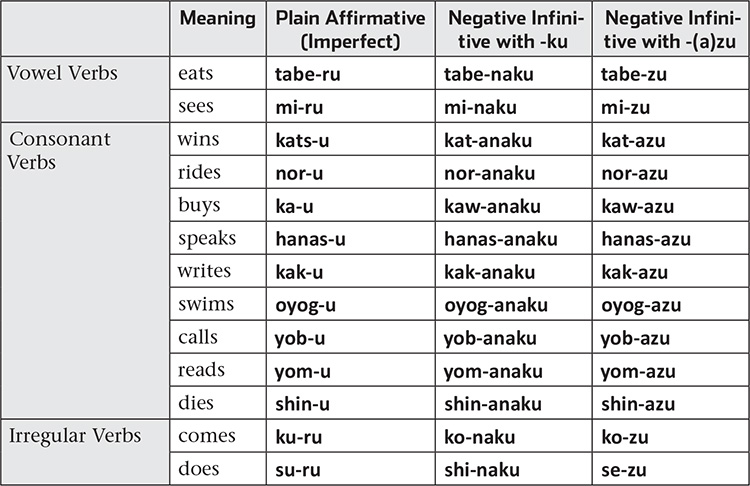

5.12. Negative infinitive …ず …zu

In addition to the regular negative infinitive as in shaberanaku naru ‘gets so he doesn’t talk’ in the above example, there is a derived adjectival noun with similar meaning but different uses. This form has the ending -azu, after a consonant-ending stem, -zu after a vowel-ending stem.

Notice that the irregular verbs are ko-zu ‘not coming’ and se-zu ‘not doing’: ko-zu is similar in its irregular vowel to ko-nai, but se-zu is different from shi-nai. The appropriate form for nai is arazu, but it is not used in speech. The -(a)zu form is usually limited to a set expression with the particle ni meaning either ‘instead of doing’ or ‘without doing,’ depending on the context. Here are some examples where -(a)zu ni means ‘instead’:

大阪に行かずに岡山に行った。

Ōsaka ni ikazu ni Okayama ni itta.

Instead of going to Osaka, he went to Okayama.

クレジットカードを使わずに現金で払います。

Kurejitto kādo o tsukawazu ni genkin de haraimasu.

Instead of using my credit card, I pay by cash.

(Another way to say ‘instead’ is to use two full sentences, with the second beginning sono kawari (ni) ‘instead of that,’ as in Hon wa kawanakatta desu. Sono kawari ni zasshi o kaimashita. ‘He didn’t buy books; instead, he bought magazines.’)

Here are some examples where -(a)zu ni means ‘without’:

朝ごはんを食べずに家を出た。

Asa go-han o tabezu ni ie o deta.

He left home without having breakfast.

よく確認せずに請求書を送ってしまった。

Yoku kakunin sezu ni seikyūsho o okutte shimatta.

Without checking it carefully, I mailed out the bill.

5.13. Imperfect negative + de …ないで …nai de

Instead of using -(a)zu ni to say ‘instead of doing’ or ‘without doing,’ you can use the plain imperfect negative -(a)nai + the copula gerund de ‘being.’ This construction is also sometimes used with kudasai in direct negative requests: Amari hanasanai de kudasai ‘Please don’t talk too much.’

大阪に行かないで岡山に行った。

Ōsaka ni ikanai de Okayama ni itta.

Instead of going to Osaka, he went to Okayama.

朝ごはんを食べないで急いで家を出た。

Asa go-han o tabenai de isoide ie o deta.

He left home in a rush without having breakfast.

ここでタバコを吸わないでください。

Koko de tabako o suwanai de kudasai.

Please do not smoke here.

運転しなくてはいけないのでお酒を飲まないでおきます。

Unten shinakute wa ikenai no de o-sake o nomanai de okimasu.

As I have to drive, I won’t drink (so I can drive later).

5.14. はず hazu

Hazu is a NOUN meaning something like NORMAL EXPECTATION or OBJECTIVE CONCLUSION. Being preceded by a modifier clause and followed by some form of the copula, it means ‘is (supposed) to, is expected to,’ but not ‘supposed to’ in the sense of obligation ‘ought to.’

Note the hazu expresses what is generally expected, and usually refers to what the speaker expects of “other” people or things; it is sometimes close to …ni chigai nai ‘there is no doubt that.’ To make the negative, you usually say hazu wa nai (rather than hazu ja nai); or, you can make the preceding verb negative: Tanaka-san wa kuru hazu wa arimasen, or …konai hazu desu ‘Mr. Tanaka surely won’t come.’ Also note that the predicates before hazu are in the prenominal form (the form required when placed before a noun) because hazu is a noun.

田中さんはしっかりしていますから,きっと確認をとったはずです。

Tanaka-san wa shikkari shite imasu kara, kitto kakunin o totta hazu desu.

Mr. Tanaka is very reliable, so he must have checked it.

あの人はお金をもらうとすぐ使うから,お金があるはずがありません。

Ano hito wa o-kane o morau to sugu tsukau kara, o-kane ga aru hazu ga arimasen.

That person uses up all the money he has (each time), so there is no way for him to have money (now).

あの人は生活保護を受けているから収入は高くないはずです。

Ano hito wa seikatsu hogo o ukete iru kara shūnyū wa takaku nai hazu desu.

He is on social welfare, so his income cannot be high.

今,1ドルは110円のはずです。

Ima, ichi-doru wa hyaku-jū-en no hazu desu.

I suppose a dollar is 110 yen now.

伊藤さんはよく居酒屋に行きますから,お酒が好きなはずです。

Itō-san wa yoku izakaya ni ikimasu kara, o-sake ga suki na hazu desu.

Mr. Ito often goes to izakaya bars, so he must like liquor.

来るはずの人が来ないと困ります。

Kuru hazu no hito ga konai to komarimasu.

When people who are expected to come don’t come, we get into trouble.

5.15. ところ tokoro

The noun tokoro ‘place’ has several special uses. When you speak of going to a person, doing something at a person’s (place), coming from a person, in Japanese you usually say ‘to, from, or at the PLACE of that person.’ In fact tokoro is used when you are going to anything that is not itself a place.

クライアントのところまで車で行きました。

Kuraianto no tokoro made kuruma de ikimashita.

I went to my client’s place by car.

Tokoro can also refer to time as well as place. It then means ‘the time or occasion when something is (was) happening,’ and it is followed by the copula or by a particle. Here are some of the expressions that result:

読むところです。

Yomu tokoro desu.

He is (just) about to read.

読むところでした。

Yomu tokoro deshita.

He was (just) about to read.

読んだところです。

Yonda tokoro desu.

He has just (now) read.

読んだところでした。

Yonda tokoro deshita.

He had just (then) read.

読んでいるところです。

Yonde iru tokoro desu.

He is just (now) reading.

読んでいるところでした。

Yonde iru tokoro deshita.

He was just (then) reading.

読んでいたところです。

Yonde ita tokoro desu.

He has just been reading.

読んでいたところでした。

Yonde ita tokoro deshita.

He had just been reading.

Instead of the copula, you can have the particle e followed by some clause that INTERRUPTS the action of the clause preceding tokoro:

賄賂を受け取ったところをカメラで撮った。

Wairo o uketotta tokoro o kamera de totta.

I took a photo of the moment when he received the bribe.

ネットカフェへ入って行くところを見ました。

Netto kafe e haitte iku tokoro o mimashita.

I saw them enter the Internet café.

弁当を食べているところへ加藤さんが来ました。

Bentō o tabete iru tokoro e Katō-san ga kimashita.

Mr. Kato came just when I was eating my boxed lunch.

There are occasional opportunities for ambiguity. Jidōsha o tsukutte iru tokoro o mimashita could mean either ‘I saw them making cars’ or ‘I saw the place where they make cars.’

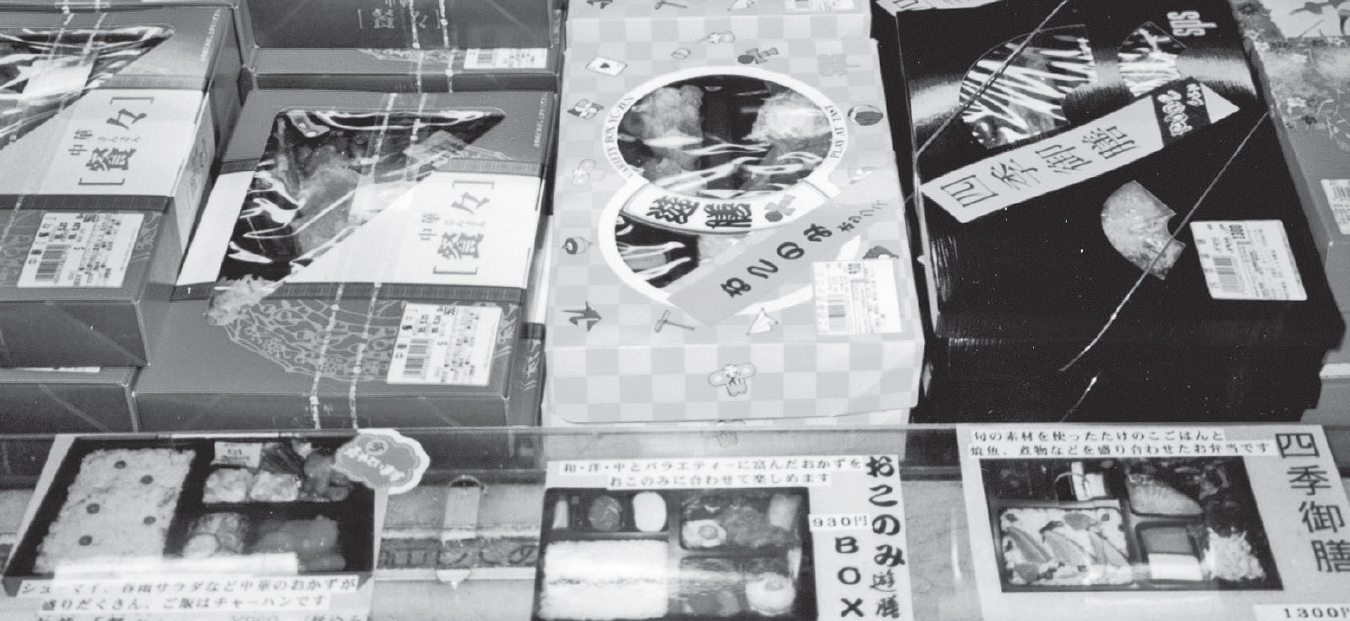

CULTURE NOTE Bentō

Bentō is a single-serving meal in a box purchased at a bentō shop or prepared at home. Some business people eat lunch at a restaurant near their office, but others bring bentō to their office daily. It saves them time and money, and is healthier. There are many cute bentō boxes sold in Japan.

5.16. Verbs for leaving

The usual verb for ‘leave’ is deru. There is a compound verb dekakeru consisting of the infinitive of deru (de) + -kakeru ‘begins to, starts to.’ This is often used when a person leaves on an errand, with the implication that he gets started on his way.

ちょっと出かけてきますね。

Chotto dekakete kimasu ne.

I’ll go out (for an errand), okay?

If a person leaves town on a trip, you use a special verb, tatsu, which means ‘leaves’ or ‘takes off (airplane),’ but you can use deru ‘leaves’ instead. The place you leave is followed by the object particle o. The verb for ‘arrives’ is tsuku; the particle for the place is e or ni ‘to.’

新幹線こだま5号が今東京駅を出ました。

Shinkansen Kodama go-gō ga ima Tōkyō eki o demashita.

Shinkansen (bullet train) Kodama #5 has just left Tokyo station.

明日パリへ発ちます。パリに午後3時に着きます。

Ashita Pari e tachimasu. Pari ni gogo san-ji ni tsukimasu.

I’ll leave for Paris tomorrow. I’ll arrive at Paris at three p.m.

5.17. …前に …mae ni and …後で …ato de

To say ‘before something happens’ or ‘before something happened,’ you use the imperfect mood followed by mae ni ‘in front of…, in advance of.…’ To say ‘after something happens’ or ‘after something happened,’ you use the perfect mood followed by ato ni ‘being after….’ Note that ato ni can also be substituted by ato de. (Ato de sounds more colloquial than ato ni.)

晩ご飯を食べる前に山田さんに電話をしました。

Ban go-han o taberu mae ni Yamada-san ni denwa o shimashita.

Before eating dinner, I called Ms. Yamada.

晩ご飯を食べた後 に/で 映画を見に行きました。

Ban go-han o tabeta ato ni/de eiga o mi ni ikimashita.

After eating dinner, I went to see a movie.

Notice that you always use the same mood in front of these two expressions regardless of the English translation:

IMPERFECT + mae ni

PERFECT + ato ni

The differences of tense in English are mostly conditioned by the tense of the verb in the final clause, and this is all indicated by the mood of the final verb in the Japanese sentence.

Now you have had two ways to say ‘after doing something’: GERUND (-te) + kara and PERFECT (-ta) + ato ni/de. The principal difference of use is that the -te kara construction refers to actions IN SEQUENCE (either time sequence or logical sequence), whereas -ta ato ni is used for actions not necessarily in immediate sequence, just separated in time. Go-han o tabete kara, eiga o mi ni ikimashita ‘I went to see a movie after eating’ implies that there is a direct sequence, with nothing else of importance happening between the time I ate and the time I saw the movie: I saw the show right after dinner. Go-han o tabeta ato ni, eiga o mi ni ikimashita ‘I went to see a movie after I had eaten’ does not imply this sequence. Perhaps I did the dishes, studied for a while, and then went for a walk before taking in a late show. Additional examples:

新幹線が出る前にホームで駅弁とお茶を買いました。

Shinkansen ga deru mae ni hōmu de ekiben to o-cha o kaimashita.

I bought a (station) lunchbox and tea at the platform before the train left.

会議が終わった後に部長と食事をしました。

Kaigi ga owatta ato ni buchō to shokuji o shimashita.

After the meeting had ended, I dined with the division manager.

仕事が終わってから居酒屋に行きます。

Shigoto ga owatte kara izakaya ni ikimasu.

I go to izakaya after finishing my work.

There are two other things to notice about mae and ato. Mae refers either to space or to time—‘before’ or ‘in front of.’ Ato usually refers only to time ‘after’—for space you ordinarily use ushiro ‘behind.’ The second thing is that mae and ato are nouns and may be modified by prenouns (kono, sono, ano, etc.) or by a noun + the particle no. For example: kono mae ‘before this,’ sono ato ‘after that,’ sensō no mae ‘before the war,’ go-han no ato ‘after the meal.’

この前にどこにいましたか。

Kono mae ni doko ni imashita ka.

Where were you before?

少し後でいいですか。

Sukoshi ato de ii desu ka.

Is it all right (if I do it) a little later?

後で見てください。

Ato de mite kudasai.

Please look at it later.

前にも後ろにもありますよ。

Mae ni mo ushiro ni mo arimasu yo.

We have some both in front and behind.

5.18. まで made and うち uchi

The particle made after a noun means ‘as far as, up to’; after the imperfect mood of a verb or the infinitive (-ku) of some adjectives, it means ‘until something happens or is’:

次の電車が来るまで駅で待ちましょう。

Tsugi no densha ga kuru made eki de machimashō.

Let’s wait at the train station until the next train comes.

次の電車が来るまで駅で待ちました。

Tsugi no densha ga kuru made eki de machimashita.

I waited at the train station until the next train came.

毎日遅くまで仕事をします。

Mainichi osoku made shigoto o shimasu.

Every day I work until very late.

The noun uchi means ‘interval, inside’ (the derived meaning ‘house’ is a specialized example of this). Following a verb or an adjective in the imperfect mood, it means ‘while someone/something is/was doing something or in a certain way.’ Uchi may be followed by ni, wa, or ni wa and is used when there is a benefit of doing some action in the specified period. In many cases uchi and aida seem interchangeable, both meaning ‘(during) the interval.’ However, aida does not have any implication about the benefit that is implied by uchi.

子供が寝ているうちに新聞を読みます。

Kodomo ga nete iru uchi ni shinbun o yomimasu.

While the children are asleep, I’ll read a newspaper.

明るいうちに運転しましょう。

Akarui uchi ni unten shimashō.

Let’s drive while it is still light.

若いうちに頑張りなさい。

Wakai uchi ni ganbari nasai.

Work hard while you are young.

After a negative, uchi means ‘while something (still) doesn’t happen; as long as something (still) isn’t so,’ and this is a common Japanese way to say ‘before something happens, before something is so’:

忘れないうちに薬を飲みましょう。

Wasurenai uchi ni kusuri o nomimashō.

Let’s take medicine before we forget.

警察が来ないうちに逃げよう。

Keisatsu ga konai uchi ni nigeyō.

Let’s run away before the police come.

暗くならないうちに帰った方がいいよ。

Kuraku naranai uchi ni kaetta hō ga ii yo.

It’s better to go home before it gets dark.

5.19. Verbs meaning ‘know’

There are two verbs often translated ‘knows’: shiru and wakaru. Shiru takes a direct object. When affirmative, it is most often used together with iru.

このことを知っていますか。

Kono koto o shitte imasu ka?

Do you know this (fact)?

In the negative, it occurs without the iru:

知りません。

Shirimasen.

I don’t know.

This verb is used for knowing specific facts and people:

「小林さんを知っていますか。」

“Kobayashi-san o shitte imasu ka.”

“Do you know Ms. Kobayashi?”

「いいえ,知りません。」

“Īe, shirimasen.”

“No, I don’t know (her).”

「駅前に新しい喫茶店ができたのを知っていますか。」

“Eki mae ni atarashii kissaten ga dekita no o shitte imasu ka.”

“Do you know that a new coffee shop opened in front of the train station?”

「ええ,知っています。」

“Ē, shitte imasu.”

“Yes, I know.”

The verb wakaru means ‘is distinguished, is understood.’ This verb does not take a direct object—the word corresponding to the English object is the subject (just like eiga ga suki desu ‘I like movies’):

「この言葉の意味が分かりますか。」

“Kono kotoba no imi ga wakari masu ka.”

“Do you understand the meaning of this word?”

「いいえ,分かりませんね。」

“Īe, wakarimasen ne.”

“No, I don’t get it.”

「日本語が分かりますか。」

“Nihongo ga wakarimasu ka.”

“Do you know (understand) Japanese?”

「はい。」

“Hai.”

“Yes.”

Interestingly, wakaru can also be used to mean ‘know.’

「田中さんの電話番号は分かりますか。」

“Tanaka-san no denwa bangō wa wakarimasu ka.”

“Do you know Mr. Tanaka’s telephone number?”

「すみません。ちょっと分かりません。」

“Sumimasen. Chotto wakarimasen.”

“Sorry. I don’t know.”

「あの人はだれですか。」

“Ano hito wa dare desu ka?”

“Who is that person over there?”

「すみません。ちょっと分かりません。」

“Sumimasen. Chotto wakarimasen.”

“Sorry. I don’t know.”

In addition, wakaru can also be used to respond to an instruction.

「この書類をコピーしてください。」

“Kono shorui o kopī shite kudasai.”

“Please make a copy of this document.”

「はい,分かりました。」

“Hai, wakarimashita.”

“Certainly.”

5.20. Talking a language

To say ‘he speaks English,’ you usually say in Japanese ‘as for him, English is produced,’ using the verb dekiru.

あの人は英語ができます。

Ano hito wa Eigo ga dekimasu.

That person can speak English.

「日本語ができますか。」

“Nihongo ga dekimasu ka.”

“Do you speak Japanese?”

「はい,少しできます。」

“Hai, sukoshi dekimasu.”

“Yes, a little bit.”

日本語があまりできないので,英語でお願いします。

Nihongo ga amari dekinai no de, Eigo de onegai shimasu.

I cannot speak/understand Japanese well, so please speak in English with me.

To say ‘understands English,’ you can use the verb wakaru:

誰か英語が分かる人はいませんか。

Dare ka Eigo ga wakaru hito wa imasen ka.

Is there anyone who understands English?

|

[cue 05-3] |

Conversation

Mr. Tanaka, an employee at Yamato Chemical, makes a phone call to Japan Electric.

Receptionist: 日本電気でございます。

Nihon Denki de gozaimasu.

Japan Electric.

Tanaka: 大和ケミカルの田中ですが,いつもお世話になっております。

Yamato Kemikaru no Tanaka desu ga, itsu mo o-sewa ni natte orimasu.

I’m Mr. Tanaka from Yamato Chemical. Thank you always for your help and kindness.

Receptionist: こちらこそいつもお世話になっております。

Kochira koso itsu mo o-sewa ni natte orimasu.

Likewise, we are indebted to you.

Tanaka: あのう,渡辺部長はいらっしゃいますでしょうか。

Anō, Watanabe buchō wa irasshaimasu deshō ka.

Umm, is Division Chief Watanabe there?

Receptionist: 只今席をはずしておりますが。

Tadaima seki o hazushite orimasu ga.

I’m sorry, but he is away from his desk right now.

Tanaka: ああ,そうですか。じゃあ,また後ほどお電話させていただきます。

Ā, sō desu ka. Jā, mata nochi hodo o-denwa sasete itadakimasu.

Well, I’ll call again later.

Receptionist: 申し訳ございません。宜しくお願いいたします。

Mōshiwake gozaimasen. Yoroshiku onegai itashimasu.

Sorry for the trouble. Thank you.

Tanaka: それでは失礼いたします。

Soredewa shitsurei itashimasu.

Okay, goodbye.

Receptionist: 失礼いたします。

Shitsurei itashimasu.

Goodbye.

CULTURE NOTE Business Telephone Conversations

When you make a phone call or receive one in a business context, talk in slightly higher pitch than usual and use polite language. O-sewa ni natte orimasu is almost always used at the beginning of a telephone conversation in a business context. Sewa means ‘care’ or ‘assistance,’ and the phrase literally means that ‘I am always being taken care of by you.’ It sounds very awkward when translated into English. Japanese tend to be apologetic in phone conversation and email communications in a business context, but it is their way of being extremely courteous. See Lesson 9 about polite language.

Exercises

I. Match the items that form a pair as contrasting or opposite items in the same category.

a. 正社員 seishain |

i. 領収書 ryōshūsho |

b. 輸入 yunyū |

ii. バイト baito |

c. 社長 shachō |

iii. 秘書 hisho |

d. 請求書 seikyūsho |

iv. 輸出 yushutsu |

II. Make a grammatical sentence by reordering the items in the parentheses, and translate the sentences.

1. (立って・人・あそこ・いる・に) は田中さんです。

(tatte, hito, asoko, iru, ni) wa Tanaka-san desu.

2. (食べ物・な・父・好き・の) はすしです。

(tabemono, na, chichi, suki, no) wa sushi desu.

3. 店は(人・多い・の・ところ)がいいです。

Mise wa (hito, ōi, no, tokoro) ga ii desu.

4. うちの会社には(いません・が・人・できる・の・英語)。

Uchi no kaisha ni wa (imasen, ga, hito, dekiru, no, Eigo).

5. (飲んで・の・いる・あの・は・人・が)お酒です。

(nonde, no, iru, ano, wa, hito, ga) o-sake desu.

III. Fill in the blanks.

|

1. アイスクリームを ————— ところです。 Aisukurīmu o ————— tokoro desu. |

|

2. アイスクリームを ————— ところです。 Aisukurīmu o ————— tokoro desu. |

|

3. アイスクリームを ————— ところです。 Aisukurīmu o ————— tokoro desu. |

IV. Change the form of the underlined part to make the sentence grammatical.

1. 日本に行きます前に日本語を勉強します。

Nihon ni ikimasu mae ni Nihongo o benkyō shimasu.

2. ご飯を食べます後に電話をします。

Go-han o tabemasu ato ni denwa o shimasu.

3. 新しい部長はあの人ですはずです。

Atarashii buchō wa ano hito desu hazu desu.

4. 部長はカラオケが好きですはずです。

Buchō wa karaoke ga suki desu hazu desu.

5. 病気ですのに会社に行くんですか。

Byōki desu no ni kaisha ni iku n desu ka.

6. 私の父はイギリス人ですんです。

Watashi no chichi wa Igirisu-jin desu n desu.