On August 7, 1942, two months after the battle of Midway, an amphibious force under Rear Admiral Richmond K. (“Kelly”) Turner landed Marines on Guadalcanal (code named “Cactus”) in the remote British Solomon Islands. There the Japanese were constructing an airstrip from which they could have threatened Allied lines of supply to Australia and New Zealand. The ultimate objective of this Operation Watchtower was seizure of the major Japanese base at Rabaul, 650 miles northwest in the Bismarck Archipelago. The first six months, however, were consumed by the fight for the Marines’ new Henderson Field. In it, each side sought to reinforce its own ground forces while preventing the enemy from doing the same – the Americans by day at first and the Japanese in night-time runs soon known as the “Tokyo Express.”

The result was a stalemate. By mid-October, however, US surface forces had become vulnerable to daylight air attack and, thanks to the Allies’ “beat Germany first” strategy, were so stretched for resources that bluejackets had nicknamed it Operation “Shoestring.” A switch to night operations set the stage for the type of surface warfare for which the Japanese had carefully prepared: with superior optics, pyrotechnics, and torpedoes, and experience in using them, they threatened to gain control of the sea. Against this, the US Navy threw cruiser–destroyer task forces. These were normally commanded by a rear admiral riding in a cruiser, who regarded his 6- or 8-inch guns as the primary weapon and deployed his ships accordingly, with destroyers attached in the van and rear, from where they could use their torpedoes for close-in defense.

No one drilled harder than the 5-inch gun crews, who used a practice loading machine mounted on deck. A typical projectile weighed about 55 lb; a brass cartridge case weighed another 28 lb. The loading process varied with gun elevation. By the time a new ship entered the war zone, gun crews could fire 20 shells per minute. Nicholas, 1943. (NARA 80-G-52854)

Two months into Watchtower, Nicholas, O’Bannon, and Fletcher arrived – the latter under Commander William M. Cole, who had just completed a tour working on radar at the Naval Research Laboratory, which made him an ideal choice to command the name ship of this highly visible new class. During training as Fletcher crossed the Pacific, he and his executive officer, Lieutenant Commander Joseph C. Wylie, Jr., began to rethink their equipment arrangement and use of personnel in battle to capitalize on the SG’s full potential.

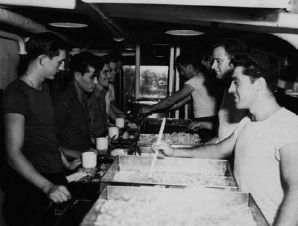

Chow line. With 330 or more officers and men on board, food was always being served on a wartime destroyer. Nicholas, 1943. (NARA 80-G-52058)

Mess deck, with berths stowed. Nicholas, 1943. (NARA 80-G-51696)

In the early hours of November 13, O’Bannon and Fletcher were in the formation when Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan’s Task Force 67 – four destroyers in the van followed by five cruisers and then four more destroyers in column – stood into soon-to-be-named “Ironbottom Sound” off Guadalcanal to intercept a vastly superior bombardment force that included two battleships. The two forces intermingled before opening fire. In the ensuing 30-minute melee, Admiral Callaghan was killed and cruiser Atlanta and four destroyers were sunk, but the Japanese lost battleship Hiei and two destroyers, and withdrew.

Although they were poorly utilized, the two 2,100-tonners fought effectively. Last among the van destroyers, O’Bannon fired three torpedoes at Hiei from 1,200 yards and emerged from the battle with little damage. Last in line overall, Commander Cole in Fletcher used his radar to open gun and torpedo fire without damage. After the battle, the two destroyers joined cruisers Helena, San Francisco, and Juneau plus 1,500-tonner Sterett in retiring and were still in company the following day when Juneau was torpedoed by a submarine and sunk.

Together with a battleship action two nights later, the battle of Guadalcanal wrested the initiative from the Japanese and prompted President Roosevelt to comment that it seemed the war’s turning point had been reached.

Two and a half weeks later, on November 30, the Tokyo Express stood in again from Bougainville with eight destroyers, six of which carried drums of provisions to be dumped overboard near Guadalcanal’s Tassafaronga (Tasivarongo) Point. In anticipation, Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr. ordered Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright to intercept with a reconstituted Task Force 67. Wright, who had assumed command only two days before, adopted an operations plan left by his predecessor, Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid. He placed Fletcher in the van with 1,500-tonners Perkins, Maury, and Drayton, to stand 4,000 yards on the engaged bow of his cruiser formation and attack with torpedoes when ordered. His five cruisers followed, with destroyers Lamson and Lardner attached en route.

|

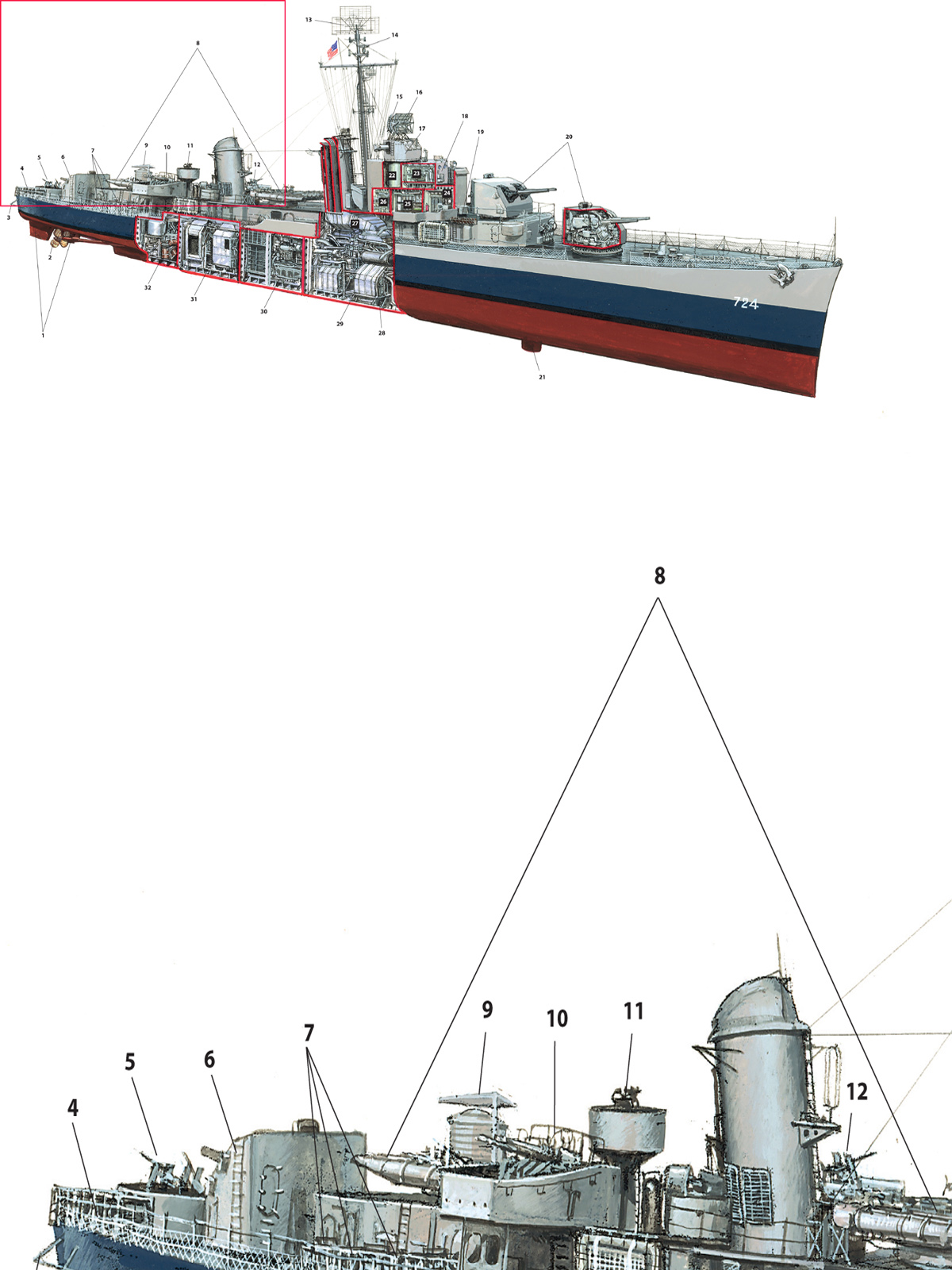

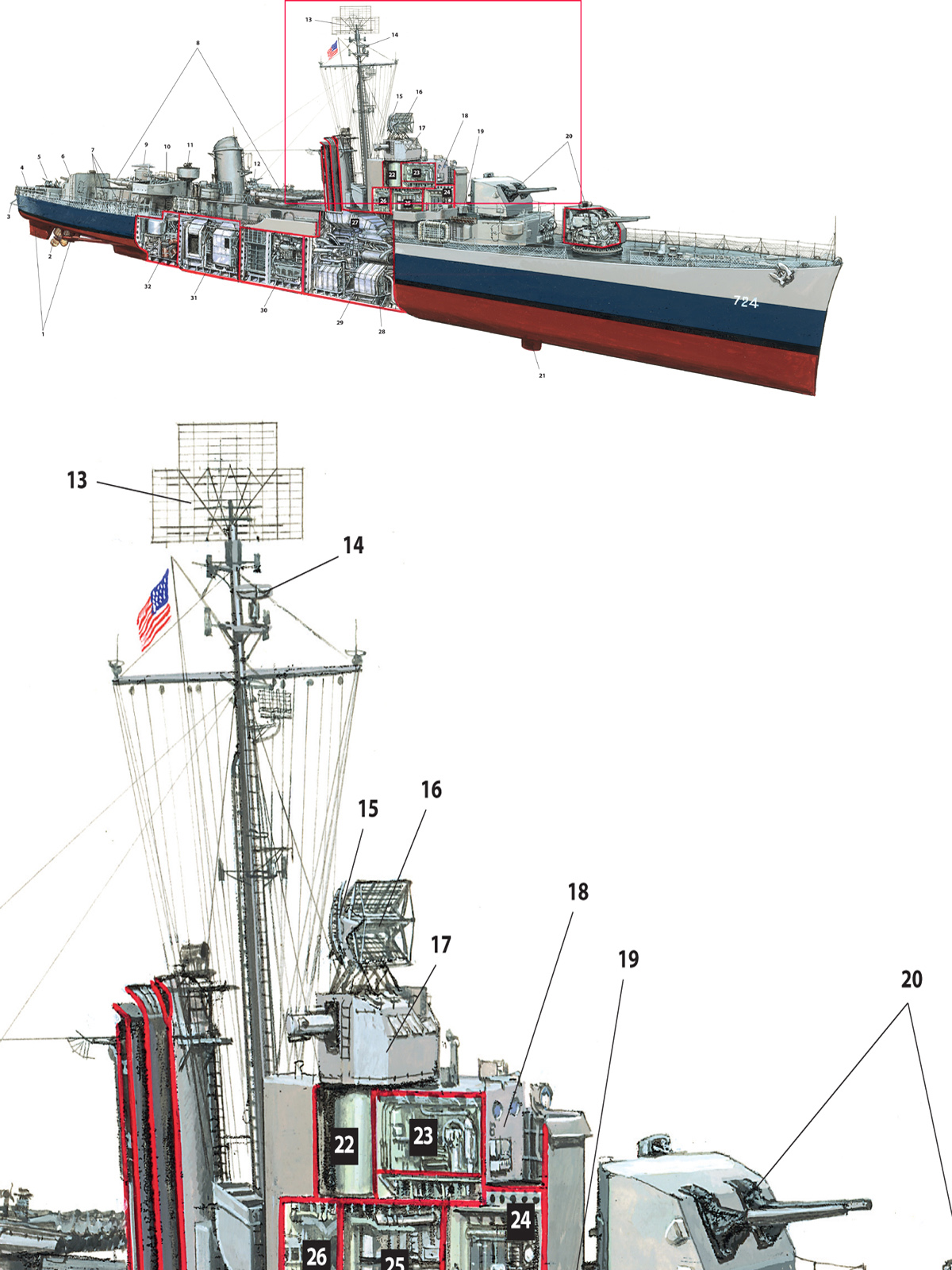

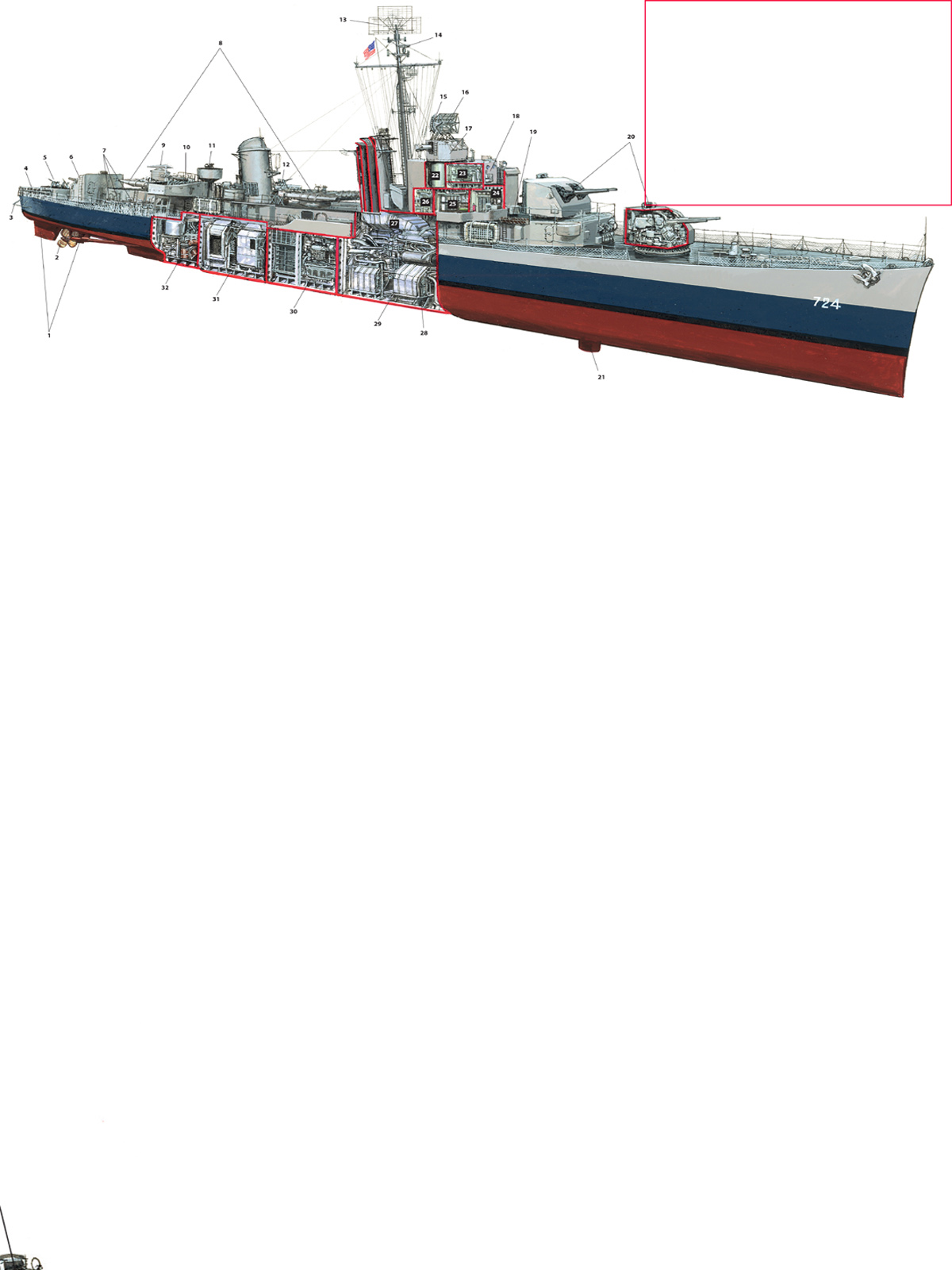

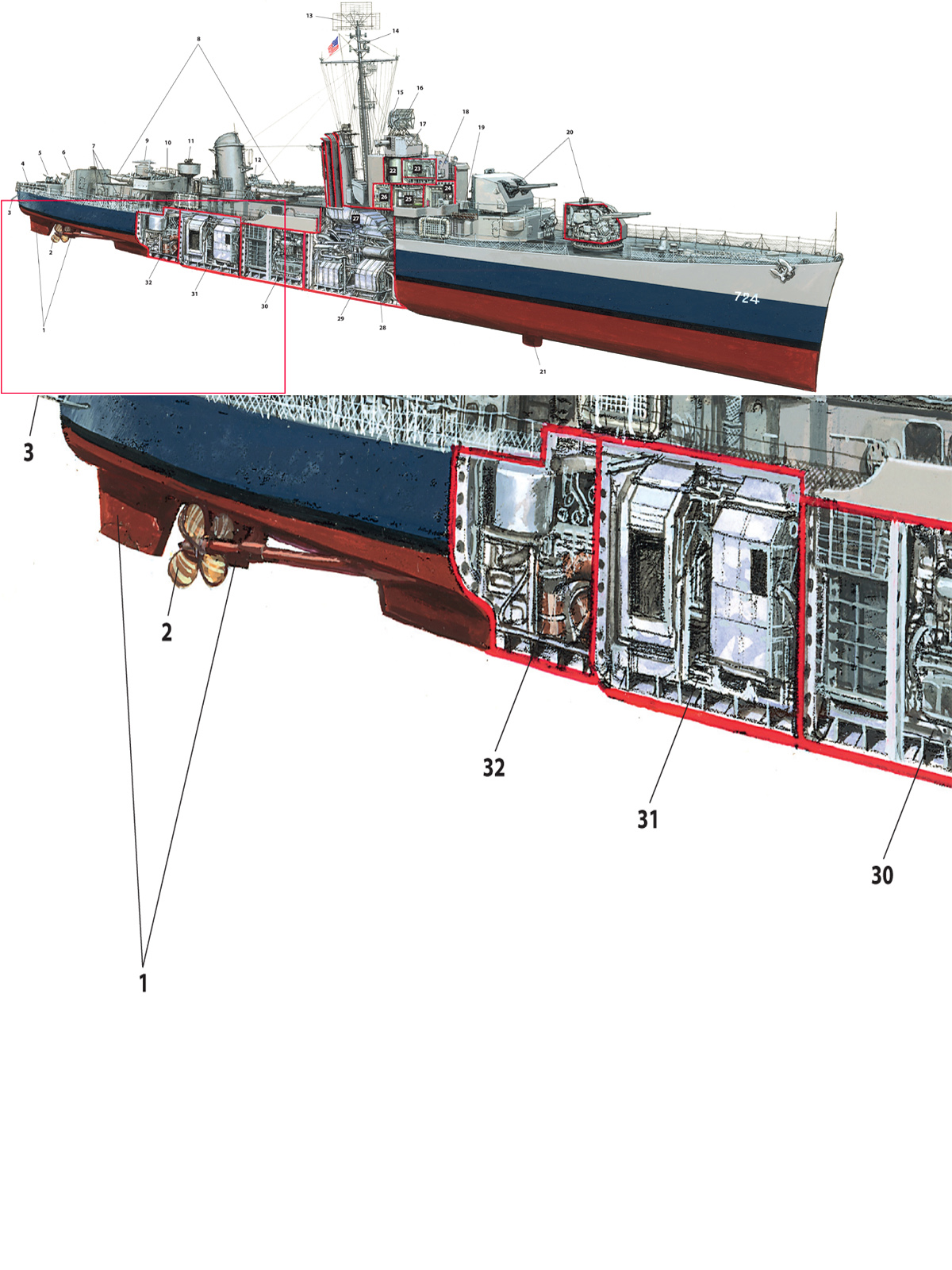

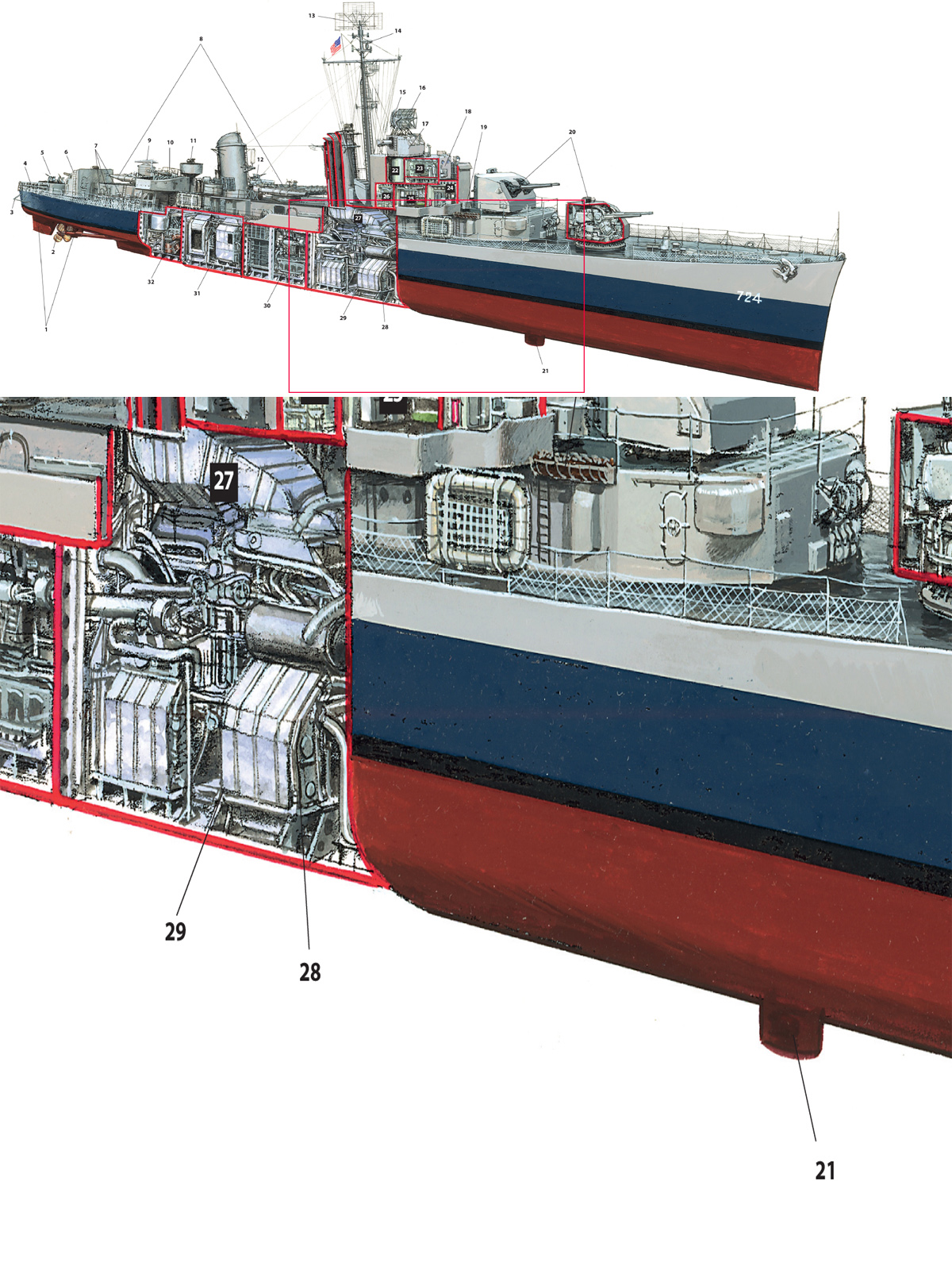

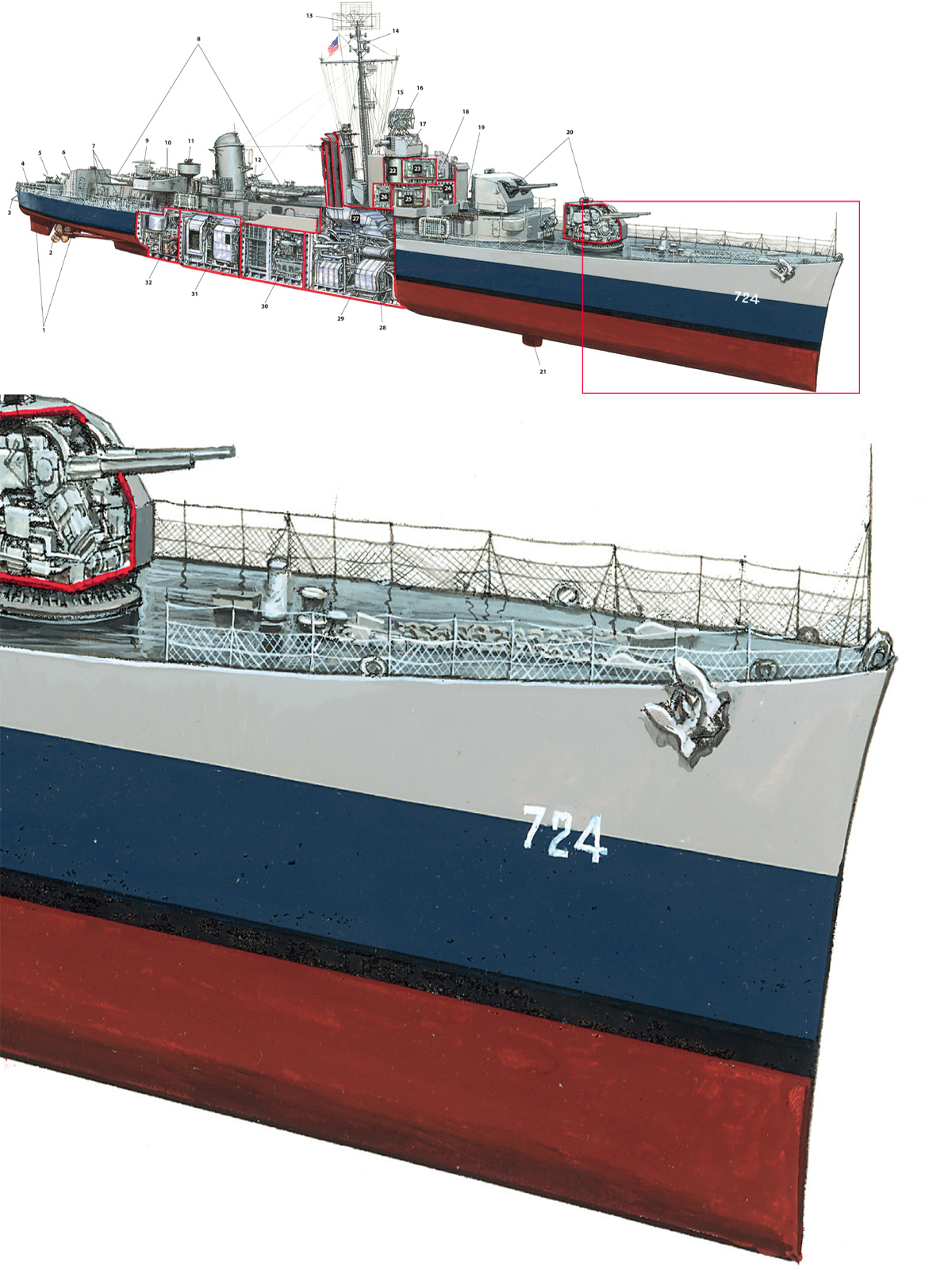

USS LAFFEY (DD 724), 1945 There were two USS Laffeys in World War II, both of which received the Presidential Unit Citation. The second of these was an Allen M. Sumner-class 2,200-tonner built at Bath Iron Works and commissioned on February 8, 1944. Attached to Destroyer Division 119, the new Laffey supported the D-Day landings at Normandy in June. After a refit at Boston, she joined the Pacific war at Leyte in November. |

| On April 16, 1945, Laffey was the lone destroyer assigned to radar picket station No. 1, 50 miles north of the Okinawa transport area (see page 38), when her radar operator began counting 50 bogies closing fast. Attacked by 22 Japanese bombers and suicide aircraft over the following 80 minutes, she splashed nine enemy planes but was struck by five kamikazes and four bombs. Three other planes and a Corsair of her CAP also grazed her; near misses caused additional damage. | |

| The onslaught knocked out most of her guns, killed 32, and wounded 71 of her 336-man crew. She remained afloat with her engineering spaces intact, however, thanks in no small measure to the fine shiphandling of her skipper, Commander F. Julian Becton. For this, the most celebrated single-ship anti-kamikaze action of the war, Laffey was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation and gained the nickname “The Ship That Would Not Die.” | |

| Repaired at Seattle by September, Laffey remained in commission until 1947. During a second period in commission, 1951–75, she was modified from her late-World War II appearance. In 1981, Laffey was placed on display at the Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum, Mount Pleasant, South Carolina and is the only remaining Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer. |

HULL AND TOPSIDES

1. Rudders

2. Starboard propeller

3. Propeller guard

4. Depth charge track

5. 20mm single mounts

6. 5-inch/38 twin mount

7. “K-gun” depth charge projectors

8. Quintuple 21-inch torpedo tube mounts

9. Torpedo loading crane

10. 40mm quad mount

11. Mark 51 40mm gun director

12. 20mm single mount

13. SC air search radar antenna

14. SG surface search radar antenna

15. Mark 22 height-finding radar antenna

16. Mark 12 fire control radar antenna

17. Mark 37 gun director

18. Navigating bridge

19. Floater net basket

20. 5-inch/38 twin mounts

21. Sonar

INTERIOR

22. Captain’s sea cabin

23. Pilot house

24. Unit commander’s cabin

25. Chart house

26. Combat Information Center

27. Boiler uptakes

28. Boiler

29. orward fireroom

30. Forward engine room

31. After fireroom

32. After engine room

Life on board was crowded, especially in the enlisted men’s washroom. Nicholas, 1943. (NARA 80-G-56063)

The battle began when Commander Cole conned Fletcher into a favorable position for a torpedo attack and requested permission to execute. Four critical minutes passed before Admiral Wright granted it, however; then, a minute later – before any torpedoes could have hit – he ordered his cruisers to open gunfire. Japanese destroyer Takanami was sunk but, in keeping with their own doctrine, other Japanese destroyers maneuvered on their own initiative, launched torpedoes, and escaped. The result: heavy cruisers Minneapolis, New Orleans, and Pensacola were damaged and Northampton sunk (Fletcher rescued 742 survivors and Drayton 128).

In his action report, Admiral Wright praised his cruisers’ gunnery performance but criticized his destroyers for wasting torpedoes, a view Admiral Halsey unfortunately endorsed, and as 1943 began, task force commanders continued to tie destroyers closely to their cruiser formations during combined night operations. With fresh experience from the two November battles, meanwhile, Fletcher’s officers took to their motor whaleboat to brief other destroyers about using the SG in action and in June 1943, when a new “Combat Information Center” (C.I.C.) school was established at Pearl Harbor, Lieutenant Commander Wylie was brought in to author the first C.I.C. Handbook for Destroyers for distribution throughout the US and Royal Navies.

On December 11, Captain Robert P. Briscoe, ComDesRon 5, embarked in Fletcher and made her his flagship for Task Unit 31.2, the “Cactus Striking Force,” operating under Admiral Turner’s direct orders. Joined by Nicholas, O’Bannon, and the newly arrived Radford and De Haven, the striking force operated in Guadalcanal waters into the new year. On January 24, 1943, Radford was credited as the first ship to shoot down an enemy plane under full radar control without sighting it. On February 1, De Haven was sunk in an air raid – the first 2,100-tonner lost.

Mail call on the fantail. Nicholas, 1943. (NARA 80-G-57615)

Other 2,100-tonners, too, began arriving following their detachment from supporting Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa in November. On January 29–30, Chevalier, Conway, La Vallette, Taylor, and Waller were screening a cruiser formation near Rennell Island south of Guadalcanal when Japanese torpedo planes attacked twice, sinking cruiser Chicago and torpedoing La Vallette.

Little more than a week later, on February 8, the Tokyo Express completed the evacuation of Guadalcanal.

Admiral Halsey now looked toward the New Georgia group of islands, the next major step up the Solomon Islands chain. Joining him were two new task force commanders, Rear Admiral Walden L. (“Pug”) Ainsworth and Rear Admiral A. S. (“Tip”) Merrill. Each commanded a division of four light cruisers, all of which mounted 12 or 15 6-inch guns, which were capable of a tremendous volume of firepower. On March 13 the US Navy was reorganized, with Halsey’s South Pacific Force designated as the Third Fleet. Within it, the first two nine-ship squadrons of 2,100-tonners were attached: DesRon 21 to Ainsworth’s Task Force 37 and DesRon 22 to Merrill’s Task Force 38.

Commanding DesDiv 43 under Admiral Merrill was Commander Arleigh A. Burke, who had arrived in the theater on February 5. A voracious reader, newcomer Burke studied the action reports from Tassafaronga. From these, he gleaned what Commander Cole had seen: that destroyers could use their weapons to best advantage only if allowed to maneuver independently, as waiting for orders took too much time.

Radford distinguished herself by rescuing 468 Helena survivors after the battle of Kula Gulf. Still deep in enemy waters at sunrise the morning after the battle, she and Nicholas raced home at 36 knots to Tulagi Harbor, where cruiser crews manned the rails in salute as they stood in. Both ships were awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for this action. (Courtesy Vane Scott, USS Radford National Naval Museum, Newcomerstown, Ohio)

Fletcher-class destroyer squadrons formed in March 19431

| Squadron | Division | Ships |

| DesRon 212 | DesDiv 41 | Chevalier, Nicholas,F O’Bannon, Strong, Taylor |

| DesDiv 42 | Fletcher,D Jenkins, La Vallette, Radford | |

| DesRon 223 | DesDiv 43 | Philip, Pringle, Renshaw, Saufley, WallerF |

| DesDiv 44 | Conway,D Cony, Eaton, Sigourney |

F Squadron flagship D Division flagship

1 De Haven was lost before squadrons were formed.

2 Hopewell and Howorth later joined DesRon 21 as replacements for Strong and Chevalier.

3 Converse was originally attached to DesDiv 44 but was reassigned to DesRon 23 in October 1943, when Sigourney replaced her in DesRon 22.

The two admirals were already leading offensive operations northwest into New Georgia Sound, by then known as the “Slot.” Back on January 5, Admiral Halsey had dispatched Admiral Ainsworth to bombard an airstrip 200 miles northwest at Munda Point on New Georgia Island; on January 24, the target was the Vila Plantation on nearby Kolombangara Island, through which Munda was being supplied. On March 5, the two task forces had operated together: while Admiral Ainsworth bombarded Munda from the south, Admiral Merrill, with Commander Burke embarked in Waller, entered Kula Gulf to the north. There, Waller torpedoed one of two Japanese destroyers surprised and sunk by her bombardment group.

On May 8, while Ainsworth and Merrill’s task forces made another bombardment run, Radford escorted flush-deck minelayers Preble, Gamble, and Breese in laying strings of mines across Blackett Strait, the western approach to Vila. These promptly sank one Japanese destroyer and damaged two others, which aircraft later finished off.

Finally, on June 30, the twofold Operation Cartwheel against Rabaul got under way. Operating from eastern New Guinea, “MacArthur’s Navy,” the yet-small Seventh Fleet under Rear Admiral Daniel E. Barbey, moved northwest toward the Bismarck Sea while in the Solomons, Rear Admiral Turner under Halsey moved against the New Georgia island group.

While Admiral Turner landed at Rendova Island, Admirals Ainsworth and Merrill continued their runs up the Slot, where Ainsworth found the enemy. On the night of July 5, as his force of cruisers Honolulu, Helena, and St. Louis with DesDiv 41’s Nicholas, Strong, Chevalier, and O’Bannon completed a bombardment run off Bairoko Harbor in Kula Gulf, Strong was hit by a “Long Lance” torpedo fired by undetected destroyers 11 miles distant. She sank as Chevalier took off her crew while O’Bannon answered shore battery fire.

|

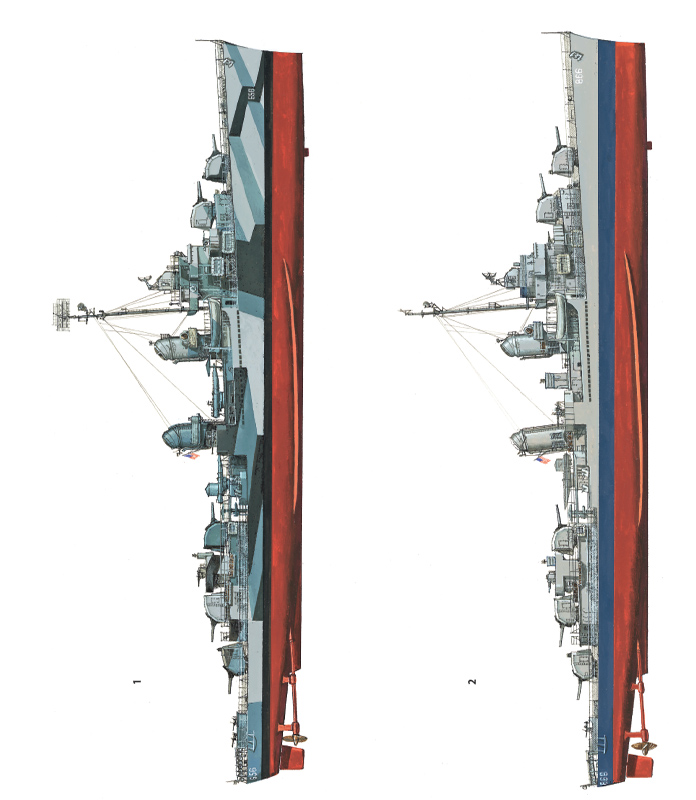

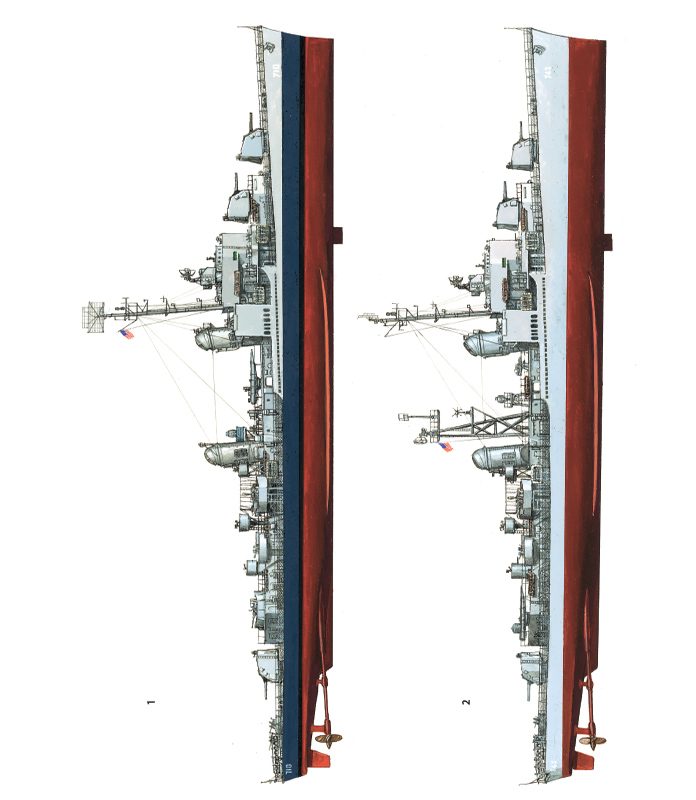

1) USS VAN VALKENBURGH (DD 656), 1945 Flagship of DesRon 58, Van Valkenburgh logged 63 consecutive days on station at Okinawa and earned a Navy Unit Commendation for defeating all enemy efforts to destroy her. The square-bridge “Van” also had an ice-cream machine, a piano, and a dog that gave birth to puppies on the way home from the war. Here she appears as built in camouflage Measure 31/9D. |

| 2) USS CLARENCE K. BRONSON (DD 668), 1945 Among the Fletchers that received the “emergency” anti-kamikaze fit in 1945, in which the forward bank of torpedo tubes was replaced by a pair of 40mm quads, were the five destroyers of Division 99. Here, DesRon 50 flagship Clarence K. Bronson appears in camouflage Measure 22. Like many destroyers late in the Pacific war, she carries her hull numbers high on the bow. |

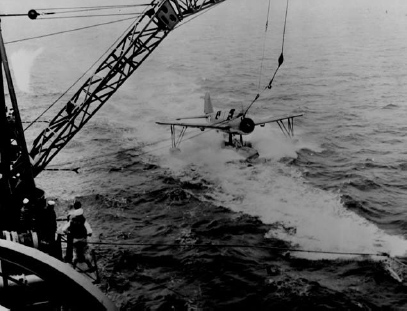

Torpedo cranes were used often in the Solomon Islands. Here at Tulagi, Nicholas replenishes torpedoes after the battle of Kula Gulf. (NARA 80-G-57600)

En route home, Ainsworth reversed course on new orders from Halsey, exchanged Chevalier for Jenkins and Radford, and that next night caught a 10-destroyer Tokyo Express just as it stood into Kula Gulf. His gunfire sank flagship Niizuki and damaged five other destroyers but he lost Helena to three more Long Lances. In retiring, he left behind Nicholas and Radford, which held off enemy destroyers until dawn while rescuing nearly two-thirds of Helena’s crew.

On the 12–13th Ainsworth, with the New Zealand cruiser Leander replacing Helena as well as ten destroyers – DesRon 21’s Nicholas, O’Bannon, Taylor, Radford, and Jenkins in the van – intercepted another southbound Japanese force and again sank the flagship, cruiser Jintsu, in exchange for a torpedo hit on Leander. The battle was not over, however. Ainsworth sent Nicholas, O’Bannon, and Taylor in pursuit of the enemy but then lost track of them and hesitated to open fire when pips reappeared on his radar. These pips then turned and ran, suggesting an enemy force that had just fired torpedoes. Before he could react, Honolulu and St. Louis were also hit and 1,630-ton destroyer Gwin was sunk.

Late July saw multiple changes. Rear Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson replaced Admiral Turner as amphibious force commander; Destroyer Squadron 23 arrived to replace DesRon 22 in Merrill’s task force; and reports of the capabilities of a dissected Japanese torpedo were circulated: the Americans were up against a weapon of unsuspected power and speed, and, with Ainsworth’s cruisers out of action, the only cruisers remaining in the theater – Merrill’s – must not be risked. Happily, there was also news that the American torpedo problems had at last been identified and fixed.

Destroyer Squadron 22 flagship Waller (center) and Philip refuel at Purvis Bay, Solomon Islands, July 25, 1943. (NARA 80-G-56739)

On July 29, Commander Burke took over the striking force, now a group of 1,500-tonners, for which he devised a battle plan reflecting his earlier analyses. On August 3, Commander Frederick Moosbrugger relieved Burke and promptly applied his predecessor’s plan at the battle of Vella Gulf, August 6–7, in a superb victory, which vindicated the independent use of destroyers on the offensive and drew attention to the importance of an efficient C.I.C.

Catapulting a floatplane was one thing; recovering it was another. Here in 1943 a Vought OS2U Kingfisher taxis up to Stevens’ sea sled during a test of the ship’s aircraft handling gear. (NARA 80-G-299540)

Munda had fallen the previous day. For his next operation, Admiral Halsey adopted a new strategy: bypassing Kolombangara in favor of undefended Vella Lavella. On August 14, while DesDivs 41 and 43 covered, Taylor led flush-deck destroyer-transports in a landing at Barakoma. From then into October, Squadrons 21, 22, and 23 – this last in its debut – ran up the Slot in various combinations to disrupt destroyer and barge traffic trying to evacuate the two islands. On August 18, DesDiv 41 found the enemy off Vella Lavella’s north coast and gave battle without result. Other encounters followed, climaxing on October 7 when 1,850-tonner Selfridge with Chevalier and O’Bannon took on six enemy destroyers. Chevalier sank Yugumo but was herself torpedoed and then lost after O’Bannon rammed her.

The end of October brought the detachment of DesRon 21 from the South Pacific and the return of now-Captain Arleigh Burke to command Squadron 23. Back under his old boss, Admiral Merrill, Burke lobbied to allow his “Little Beavers” to operate offensively under a “doctrine of faith”: as soon as they sighted the enemy, they would close without orders to fire their torpedoes and then stand clear of the cruisers’ gunfire.

The invasion of Bougainville followed a week later. While the newly-arrived DesRon 45 plus three Squadron 22 veterans supported landings at Cape Torokina on Empress Augusta Bay, only 200 miles from Rabaul, Merrill and Burke launched a tightly-scheduled diversion. Just after midnight on November 1, Merrill’s four cruisers and eight destroyers bombarded airfields near the Buka Passage 50 miles north of the beachhead; the following day, they hit the Shortland Islands 70 miles south of it. Then, after Burke with DesDiv 45 (Charles Ausburne, Dyson, Stanly, and Claxton) ran south to Hathorn Sound to replenish, Merrill turned his task force north again, with his destroyers ready to attack independently with torpedoes if the enemy appeared as expected.

In mid-1943, production of 40mm twins had not yet caught up to demand. In an interim arrangement, one 20mm single was mounted on the flying bridge and another on a platform forward of the pilot house, easily seen in this photo of Thatcher. (NARA 80-G-36537)

Off Empress Augusta Bay in the early hours of November 2, Merrill’s cruisers quietly crossed ahead of a more powerful Japanese formation and withheld gunfire while first DesDiv 45 and then DesDiv 46 (Spence, Thatcher, Converse, and Foote) detached to close the enemy’s flanks. Too soon, the Japanese altered course to give battle and most of the Little Beavers’ torpedoes missed. Amid the confusion, however, Merrill opened fire and then expertly maneuvered his cruisers in a series of turns to avoid any enemy torpedoes until the Japanese retired. Carrier strikes on Rabaul over the next days broke up a heavy cruiser force assembling there and prevented the need for a repeat performance by Merrill against what would’ve been much steeper odds.

Three weeks later, Commodore Burke earned his own signal victory against the Tokyo Express. Spence’s No. 4 boiler was out of commission, which limited her best speed to 31 knots, but her skipper appealed to Burke to let him come. Burke radioed his intentions to Halsey’s staff, who began the reply message with “padding” that made light of the problem of the moment: FOR 31-KNOT BURKE ... GET ATHWART THE BUKA-RABAUL EVACUATION LINE ... IF ENEMY CONTACT YOU KNOW WHAT TO DO ...

Always studying: Captain Arleigh Burke on the bridge wing of his DesRon 23 flagship Charles (“Charlie”) Ausburne in late 1943 with the Little Beaver mascot painted outboard, forward of the life ring. (NH 59854)

“31-knot” Burke did. In the waters northwest of Bougainville in the early morning of November 25, Thanksgiving Day, he executed a masterpiece of both planning and finesse, in which he ambushed two Japanese formations. First his own DesDiv 45 (Charles Ausburne, Dyson, and Claxton) torpedoed two destroyers and left them in sinking condition, to be finished off by DesDiv 46 (Converse and Spence). Then he took off after three more approaching Japanese destroyers, which fled north. Altering course during the chase on the strength of intuition alone, he dodged an enemy torpedo spread before overhauling and sinking one of the three. Finally, after extending his pursuit to within an hour’s steaming of New Ireland Island’s Cape St. George, he turned back.

Charles Ausburne, Dyson, and Claxton engage and sink the Japanese destroyer Yugiri in The Little Beavers at the battle of Cape St. George by the aviation artist R. G. Smith. (Courtesy of Ms. Sharlyn Marsh, rgsmithart.com)

Back in August 1943, President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill had agreed that Operation Cartwheel’s objective should no longer be to seize Rabaul – with its 100,000 defenders – but to bypass and isolate it. By December, Vice Admiral Kinkaid and DesRon 24 had arrived from Alaska (see next page) to join the Seventh Fleet in time for landings at Cape Gloucester in western New Britain, where Brownson was lost. In February 1944, DesRons 22 and 45 supported the occupation of the Green Islands east of Rabaul. Later that month, they and Squadron 23 made sweeps into the Bismarcks while General MacArthur landed at Manus in the Admiralty Islands to the northwest. MacArthur completed his occupation on March 18; two days later, Admiral Wilkinson landed at nearby Emirau, closing the ring around Rabaul.

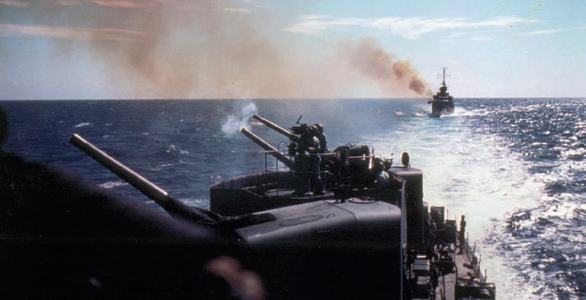

In early 1944, Halford (foreground) lobbed a few shells at a wooden watchtower in the Shortland Islands south of Bougainville. Before Bennett (background) could join in, she was straddled by 6-inch return fire. Admiral Halsey later sent the “naughty boys” a message saying the installation was already known and did not pose a threat. (NARA 80-G-K-1638)

The South Pacific was not the only Pacific front. The great circle route from Alaska through the Kurile Islands to northern Japan also beckoned, but the Aleutian Islands’ notoriously bad weather made operations difficult. Back in May 1943, the 7th Infantry Division had assaulted Attu in DesRon 24’s debut, which ended badly when Abner Read’s stern was blown off by a mine. In August it moved on to Kiska, which the Japanese had already evacuated.

That ended the campaign. Further naval operations were limited to nuisance raids and anti-shipping sweeps. In late November 1943, when DesRon 24 was ordered south to join the Seventh Fleet, DesRon 49 relieved it until it, in turn, was ordered south for the Philippines operations in 1944. DesRon 57 then arrived and its DesDiv 114 remained through June 1945, when it conducted a last sweep into the Sea of Okhotsk.

| Fletcher-class destroyer squadrons formed in mid-1943 | ||

| Squadron | Division | Ships |

| DesRon 23 | DesDiv 45 | Aulick, Charles Ausburne,S Claxton, Dyson, Stanly |

| DesDiv 46 | Converse, Foote, Spence, Thatcher | |

| DesRon 24* | DesDiv 471 | Bache, Beale, Brownson, Daly, HutchinsS |

| DesDiv 48 | Abner Read,D Ammen, Bush, Mullany | |

| DesRon 25 | DesDiv 49 | Harrison, John Rodgers,S McKee, Murray, Stevens |

| DesDiv 50 | Dashiell, Ringgold, Schroeder, Sigsbee | |

| DesRon 45 | DesDiv 89 | Bennett, Fullam,S Guest, Halford, Hudson |

| DesDiv 90 | Anthony, Braine, Terry, Wadsworth | |

In 1941, when construction of the Fletchers began, keels were also laid for the big new Essex-class carriers. In the summer of 1943, these finally began to arrive at Pearl Harbor. There, on August 5, Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance took command of the Fifth Fleet and prepared to advance across the Pacific. Joined by the new DesRon 25, he began with a “break in” raid on Marcus Island on September 1 and then one on Wake in October. By November, with 11 fast carriers, he was ready to begin his drive westward toward the Philippines in which each operation would rank as the largest concentration of naval power the world had ever seen – until the next one.

Underway replenishment was routine in the Pacific and made it possible for thirsty destroyers to operate over long distances without bases. Here Nicholas refuels from oiler Sabine in 1943. (NARA 80-G-57656)

Admiral Spruance’s first step was Operation Galvanic, the seizure of Makin and Tarawa Atolls in the Gilbert Islands, November 10–December 10, 1943. Fletchers on hand included Squadrons 25 and 47 with Admiral Turner’s amphibious forces and Squadrons 46 and 48 – as well as Squadron 21 en route home from the Solomons – with the carriers. Makin fell with relative ease. Tarawa, however, was a near catastrophe for the Marines, and it revealed multiple weaknesses. One of these was naval gunfire support, which Admiral Turner felt could be improved by 50 percent.

| Fletcher-class destroyer squadrons joining the Pacific war in late 1943 | ||

| Squadron | Division | Ships |

| DesRon 46 | DesDiv 91 | Bell, Burns, Charrette, Conner, IzardS |

| DesDiv 92 | Boyd, Bradford, Brown, Cowell | |

| DesRon 47 | DesDiv 93 | Hazelwood, Heermann, Hoel, McCord,S Trathen |

| DesDiv 94 | Franks, Haggard, Hailey, Johnston | |

| DesRon 48 | DesDiv 95 | Abbot, Erben,S Hale, Stembel, Walker |

| DesDiv 96 | Black, Bullard, Chauncey, Kidd | |

| DesRon 49* | DesDiv 97 | Picking,S Sproston, Wickes, William D. Porter, Young |

| DesDiv 98 | Charles J. Badger, Isherwood, Kimberly, Luce | |

Operation Flintlock followed: an assault on Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands, January 29–February 7, 1944. Joining Admiral Turner’s Joint Expeditionary Force were five destroyers from Squadron 51, while Squadrons 50 and 52 were added to the Fast Carrier Force, now under Rear Admiral Marc A. Mitscher. The Marshalls proved to be the easiest amphibious operation of the war, thanks to the lessons learned in the Gilberts as well as a great disparity in strength between the attacking and defending forces. Here, too, Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs) were first deployed.

So successful was Flintlock that Admiral Turner continued on to Eniwetok after only a week of planning (Operation Catchpole, January 31–March 4). In addition to providing support, Admiral Mitscher took time out for a two-day strike on Truk (Operation Hailstone, February 17–18), during which DesRon 46’s Izard, Charette, Burns, and Bradford screened battleships and cruisers in sinking enemy cruiser Katori and two destroyers.

| Fletcher-class destroyer squadrons joining the Pacific war in early 1944 | ||

| Squadron | Division | Ships |

| DesRon 50 | DesDiv 99 | Clarence K. Bronson,S Cotten, Dortch, Gatling, Healy |

| DesDiv 100 | Caperton, Cogswell, Ingersoll, Knapp | |

| DesRon 51 | DesDiv 101 | Hall,S Halligan, Haraden, Paul Hamilton, Twiggs |

| DesDiv 102 | Capps, David W. Taylor, Evans, John D. Henley | |

| DesRon 52 | DesDiv 103 | Miller, Owen,S Stephen Potter, The Sullivans, Tingey |

| DesDiv 104 | Hickox, Hunt, Lewis Hancock, Marshall | |

| S Squadron flagship | ||

Squadrons 53–56 joined the Fifth Fleet for Operation Forager against the Mariana Islands, which commenced on June 13 with the bombardment of Saipan. Vice Admiral Turner landed on the 15th; the island fell three weeks later.

The Japanese Mobile Fleet appeared on the 19th but in the two-day battle of the Philippine Sea – the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot” – lost more than 90 percent of its air wing to Spruance’s juggernaut, ending its effectiveness as a carrier force. Fifteen American carriers participated in the battle with destroyers of Squadrons 23, 45, and 50–53 in the screen. It ended with a long-range strike late on the 20th and Vice Admiral Mitscher’s memorable order to “turn on the lights” to guide his planes home after dark. Destroyers illuminated the formation with star shells and rescued pilots who had run out of fuel.

“Lifejackets? We never wore them just for this!” An unidentified Fletcher, possibly Smalley, fuels from battleship Wisconsin late in the war. (NARA 80-G-306191)

High-line transfers were a way of life at sea, where destroyers sometimes operated without dropping anchor for many weeks at a time. Here a man is pulled across from an unidentified Fletcher. (NARA 80-G-K-5624)

On July 21, Turner landed on Guam and then on Tinian. In late November, American B-29 bombers began to fly missions from the Marianas against the Japanese homeland.

Fletcher-class destroyer squadrons joining the Pacific war in mid-1944

| Squadron | Division | Ships |

| DesRon 53 | DesDiv 105 | Benham, Colahan,S Cushing,1 Halsey Powell,1 Uhlmann |

| DesDiv 106 | Stockham, Twining, Wedderburn, Yarnall | |

| DesRon 54 | DesDiv 107 | McGowan, Melvin, Mertz, Norman Scott, RemeyS |

| DesDiv 108 | McDermut, McNair, Monssen, Wadleigh | |

| DesRon 55 | DesDiv 109 | Callaghan, Cassin Young, Irwin, Porterfield,S Preston |

| DesDiv 110 | Laws, Longshaw, Morrison, Prichett | |

| DesRon 56 | DesDiv 111 | Bennion, Heywood L. Edwards, Leutze, Newcomb,S Richard P. Leary |

| DesDiv 112 | Albert W. Grant, Bryant, Robinson, Ross | |

| S Initial and/or long-term squadron flagship 1 Later flagship | ||

|

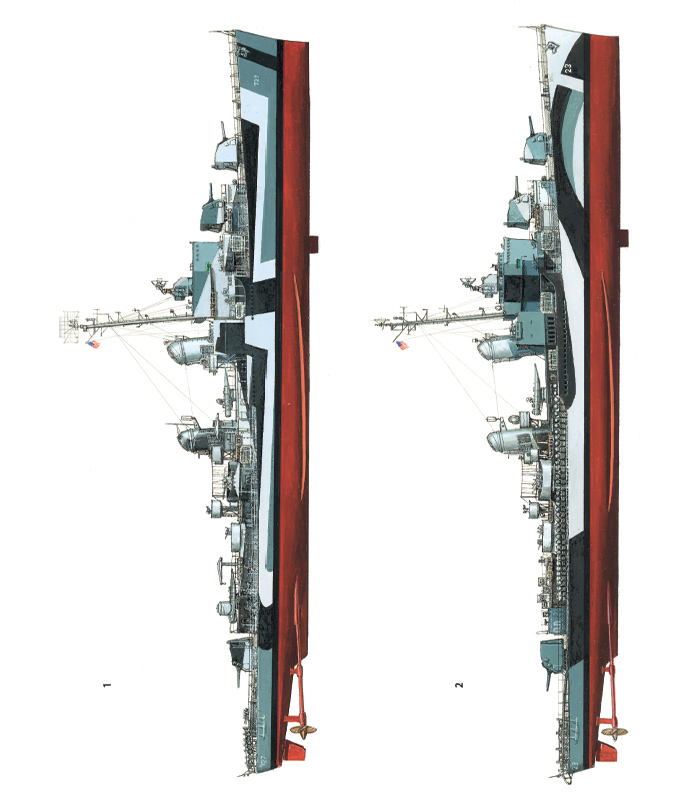

1) USS GEARING (DD 710), 1945 Lead ship of the long-hull class was Gearing, which completed at Federal’s new facility at Port Newark, New Jersey and commissioned on May 3, 1945, but did not see action in World War II. Here she appears in camouflage Measure 22, with a 40mm quad mount replacing her after torpedo tubes. |

| 2) USS SOUTHERLAND (DD 743), 1945 Southerland, Bath’s second Gearing, became the first destroyer to enter Tokyo Bay on August 28, 1945 when she led a column through the Uraga Strait to occupy the Yokosuka Naval Base. Here she appears after her conversion as a radar picket destroyer in camouflage Measure 21. Southerland and Bath-built sister Frank Knox retained their after torpedo tube mounts throughout the war. |

With Mitscher’s fast carriers, Knapp and battleship Alabama screen Lexington in 1944. (NARA 80-G-234777)

In parallel with the Fifth Fleet’s great push, General MacArthur moved west from Manus using his Seventh Fleet to leapfrog along New Guinea’s north coast (and thereby sentencing Squadrons 21, 24, and 48 to a long hot summer on the Equator). On April 22 his Army forces landed at Hollandia and Aitape supported by Admiral Mitscher, who filled another gap in his schedule with four days of strikes beginning on the 21st – also hitting Palau, Yap, and Wolaei on the way out and Truk, Ponape, and Satawan on the way home.

In May, MacArthur jumped again: 125 miles to Wakde; then 180 miles to Biak, which finally provoked a response by sea. On the night of June 8–9, Seventh Fleet cruisers and destroyers intercepted five enemy destroyers towing barges toward Biak in a Tokyo Express-type relief attempt. In a three-hour pursuit by DesDivs 42, 47, and 48, Fletcher, Jenkins, Radford, and La Vallette worked up to 35 knots, exchanged fire, scored one hit, and had closed to 10,000 yards before executing orders to break off.

Japanese resistance at Biak collapsed in late June. Next, General MacArthur seized Noemfoor Island 90 miles west on July 2, then jumped 200 miles further to Cape Sansapor on the Vogelkop Peninsula on July 30, followed by a final leap to Morotai in the Molucca (Maluku) Islands on September 15.

That same day, the 1st Marine Division landed at Peleliu in the Palau Islands. There, for the first time, the Japanese elected not to defend the beaches in favor of a “defense in depth” strategy, in which they waited until American troops were ashore and then bitterly contested every inch of ground. While bloody fighting continued until November, Admiral Spruance occupied the anchorage at Ulithi on September 23, completing his approach to the Philippines. In a change of command, his Fifth Fleet became Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet.

Not all Fletcher and Sumner operations took place in the Pacific. In the fall of 1943, Capps operated with the British Home Fleet from its base at Scapa Flow, screening the American carrier Ranger in an air strike on Bodo, Norway, followed by a mission south to Gibraltar and another one north to the Barents Sea, before joining DesRon 51 in the Pacific. After shakedown, Twiggs also operated from Norfolk as a training ship until May 1944.

That same month, the first Sumners of Destroyer Division 119 crossed the Atlantic for Operation Neptune, the Normandy invasion. Clearing Plymouth, England on June 3, they provided two weeks of gunfire support for troops ashore beginning on D-Day, June 6. The next day, while patrolling offshore, Meredith was struck by a glider bomb. She was towed clear but broke in two and sank on the 9th after near misses from German bombers opened up her seams.

Allen M. Sumner, as completed with the enclosed “British-style” pilot house, runs trials on March 26, 1944. The Sumner class was the first to incorporate a built-in C.I.C., use of which was institutionalized across the Navy in 1944. (NARA 80-G-237593)

On June 25, during the bombardment of Cherbourg, her DesDiv 119 sisters covered inshore minesweeping operations where their gunfire was so effective that they drew shore battery fire away from battleship Texas. O’Brien was damaged; ricochets also hit Barton and Laffey. The division returned to Boston for repairs and then joined Division 120 in the Pacific in the fall.

| Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer squadron formed in early 1944 | ||

| Squadron | Division | Ships |

| DesRon 60 | DesDiv 119 | Barton,S Laffey, Meredith, O’Brien, Walke |

| DesDiv 120 | Allen M. Sumner,D Cooper, Ingraham, Moale | |

| S Squadron flagship D Division flagship | ||

In the Pacific, the stage was now set for General MacArthur’s return to the Philippines. He chose the island of Leyte, which could easily be approached from the east and afforded good access to the west toward his next objective, Luzon.

| Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer squadrons formed in late 1944 and 1945 | ||

| Squadron | Division | Ships |

| DesRon 61 | DesDiv 121 | Collett, De Haven,S Lyman K. Swenson, Maddox, Mansfield |

| DesDiv 122 | Blue, Brush, Samuel N. Moore, Taussig | |

| DesRon 62 | DesDiv 123 | Ault, Charles S. Sperry, English,S Haynsworth, Waldron |

| DesDiv 124 | Borie, Hank, John W. Weeks, Wallace L. Lind | |

| DesRon 63 | DesDiv 125 | Compton,S Gainard, Harlan R. Dickson, Hugh Purvis, Soley |

| DesDiv 126 | Drexler, Hyman,D Mannert L. Abele, Purdy | |

| DesDon 64 | DesDiv 127 | Alfred E. Cunningham,S Frank E. Evans, Harry E. Hubbard, John A. Bole, John R. Pierce |

| DesDiv 128 | Buck, Henley, John W. Thomason, Lofberg | |

| DesRon 66 | DesDiv 131 | Hugh W. Hadley, James C. Owens, Putnam,S Strong, Willard Keith |

| DesDiv 132 | Douglas H. Fox, Massey,D Stormes, Zellars | |

| S Squadron flagship D Division flagship | ||

The vast majority of 2,100-tonners participated in the Leyte operation. With Admiral Kinkaid’s 650-ship Seventh Fleet were destroyers from Squadrons 21–25, 47–49, 54, and 56. With Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet were 17 carriers in four task groups screened by DesRons 46, 50, 52, 53, and 55; DesRon 51 operated with oilers and escort carriers in an At Sea Logistics Group. Of all the 2,100-tonner squadrons formed by that time, only DesRons 45 and 57 were absent.

Helm of Lowry, a late Sumner completed with the revised pilot house design. (NARA)

First to be damaged was DesRon 56’s Ross, which struck two mines during mine clearance operations on October 19. In an exhibition of exceptional toughness, she was towed clear and later entered dry dock.

On the 20th, the landings proceeded without incident. In response, Japanese surface forces sortied. While a weak Northern Force of aircraft carriers with few aircraft approached from the northeast, hoping to lure Admiral Halsey away from protecting the beachhead, a powerful Center Force steamed toward San Bernardino Strait between the islands of Luzon and Samar and two elements of a weaker Southern Force also stood toward Leyte Gulf from the west via Surigao Strait.

Opening the action on October 24, carrier Princeton was hit by a single bomb, which caused devastating explosions. DesRon 55’s Cassin Young, Irwin, and Morrison came alongside to help fight fires and take off crew members – Morrison briefly became wedged between the carrier’s stacks – and then were relieved by cruiser Birmingham, whose crew on deck was decimated when the carrier blew up. The destroyers rescued more than 1,000 carriermen.

Meanwhile, Halsey’s fast carriers under Admiral Mitscher attacked the approaching Center Force in the Sibuyan Sea, sinking battleship Musashi. Satisfied that the Center Force was retiring, he then turned to confront the Northern Force at the end of the day.

After midnight, now October 25, the Southern Force of two battleships, one cruiser, and four destroyers – followed at a distance by three more cruisers and four more destroyers – entered Surigao Strait from the south. Waiting in ambush were six battleships, eight cruisers, and 26 destroyers of Admiral Kinkaid’s Seventh Fleet.

The “square” bridge of late Fletcher-class destroyer Halligan, arranged so that officers did not have to duck through the pilot house to observe aircraft on any bearing. (NARA 80-G-264040)

As the enemy closed, destroyers from three squadrons executed consecutive torpedo attacks. First, DesRon 54’s Remey, McGowan, and Melvin attacked from the east and McDermut and Monssen from the west; then laid smoke and retired. Next, DesRon 24’s Hutchins, Daly, and Bache followed by HMAS Arunta, Beale, and Killen attacked from the west; then opened gunfire. Finally, as the Battle Line commenced gunfire overhead, Squadron 56 (with Halford replacing Ross) pressed its attack in three sections to ensure the enemy would pass “through torpedo waters, no matter which way he turns.” Overall result: both Japanese battleships and three destroyers were sunk while three cruisers were damaged, at a cost of damage only to DesRon 56’s Albert W. Grant.

Heermann (foreground) and one of Taffy 3’s John C. Butler-class destroyer escorts lay smoke screens early in the battle off Samar, October 25, 1944. (NARA 80-G-288885)

The following morning, a frantic call for help came from Rear Admiral Clifton A. Sprague’s Taffy 3, one of three formations of escort carriers screened by the nine destroyers of Squadron 47 and destroyer escorts – no match at all for the four battleships, five cruisers, and eleven destroyers of the Japanese Center Force, which had reversed course, passed through San Bernardino Strait, and was now bearing down on them.

As Taffy 3’s aircraft rose in defense, Johnston turned to lay a smokescreen and launch torpedoes. One of these nearly severed heavy cruiser Kumano’s bow before Johnston was hit by battleship Kongo. Hoel launched five torpedoes at Kongo and five at cruiser Haguro before enemy shells put her out of action. Heermann also attacked battleship Haruna with torpedoes and then tried to hold off heavy cruisers with gunfire as they closed the slow-steaming escort carriers.

Nearly an hour into the battle, Japanese flagship Yamato spotted torpedo tracks and turned away. This further broke up the Japanese formation – too late for escort carrier Gambier Bay, destroyer escort Samuel B. Roberts, and Hoel, which were sunk by shellfire. Johnston, too, went down, but not before the crew of a Japanese destroyer rendered honors as their ship passed close aboard. Posthumously, her Commander Ernest E. Evans was awarded the Medal of Honor for “... outshooting and outmaneuvering the enemy as he consistently interposed his vessel between the hostile fleet units and our carriers ...”

Two hours into their pursuit but with mounting losses and their formation in disarray, the Japanese broke off and turned back for San Bernardino Strait, leaving Taffy 3 stunned but victorious. Regrettably, survivors of the lost ships remained unrescued for three days, during which injuries, the elements, and sharks took their toll. Only 58 from Hoel and 145 from Johnston were eventually picked up, but their heroic fight resonated throughout the Navy and stands as one of the outstanding surface actions of all time.

Flagship of Taffy 3’s destroyer screen, Hoel fired torpedoes and saw two enemy columns turn away before being boxed in and sunk by more than forty heavy-caliber hits. Here she appears as commissionned in the summer of 1943. (NH 97895)

The first destroyer to engage the enemy and last to sink at Samar was “GQ Johnny.” Johnston appears here off Tacoma, Washington in a delivery photo taken October 27, 1943. (NH 63495)

Far to the north, meanwhile, Admiral Mitscher had closed the Northern Force and commenced launching air strikes an hour before Admiral Halsey received the first appeal to assist Taffy 3. Embarked with his Battle Line – screened by DesRon 52 – Halsey raced south but arrived off San Bernardino Strait too late to intercept the retreating Center Force. Owen and Miller finished off destroyer Nowaki, the lone straggler.

Hull down in a storm: an unidentified Fletcher nearly disappears in the trough of a wave. Spence was lost under far worse conditions during the great typhoon of December 1944. (NH 89375)

Mitscher’s task force, meanwhile, continued its air strikes against the Northern Force and ended the day by sending four cruisers and ten DesRon 50 and 55 destroyers to mop up.

The end of one type of battle saw the beginning of another. Before noon that same October 25, a Japanese plane crashed and sank another Taffy 3 escort carrier, St. Lo. Then on November 1 in quick succession, Claxton was damaged by a plane that crashed close aboard, Killen was bombed, Ammen was deliberately crashed, and Abner Read was sunk by suiciders. Two more 2,100-tonners were hit at the end of the month: Ross in her dry dock on the 28th and Aulick the next day. It was apparent that a severe new threat was at hand in the form of the Kamikaze Special Attack Force.

Ashore, Japanese ground forces began receiving Tokyo Express-style reinforcements via Ormoc Bay, Leyte’s west coast “back door.” Beginning on November 27, DesRon 22 destroyers made three runs through Surigao Strait to intercept. Newly-arrived DesDiv 120 drew the assignment on December 2–3 and sank one enemy destroyer but lost 2,200-tonner Cooper to a torpedo from another. Finally, on the 7th, DesDivs 41 and 119 supported amphibious landings that eventually cut off the reinforcements.

By then, General MacArthur was moving toward Luzon’s Lingayen Gulf for his planned ground advance on Manila. En route, beginning on December 12, Howorth, Haraden, Bryant, and Pringle all sustained kamikaze hits. Concurrently, Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet resumed air strikes from positions east of Luzon. There, on December 17, it was caught by a typhoon in which Spence and 1,500-tonners Hull and Monaghan were lost, and Hickox nearly so.

The Lingayen Gulf landings on January 9, 1945 followed the same general plan as previous operations, but the number and severity of air attacks increased. Suicide planes, boats, and swimmers were effective, sinking 24 ships and damaging 67. On January 6, kamikazes attacked the Bombardment and Fire Support Groups screened by DesRons 56 and 60. No Fletchers were hit, but Allen M. Sumner, O’Brien, and Walke were all damaged (Walke’s Commander George F. Davis was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for continuing to conn his ship while mortally burned).

“She always did more than her share,” said Capt. Arleigh Burke of Spence, the only 2,100-tonner lost in the great typhoon of December 1944. Here she stands off Hunters Point, California two months earlier, before her last deployment. (NARA 19-N-80398)

With the capture of Lingayen came a fine base at Subic Bay, two hours’ steaming north of Manila Bay, which was defended by Corregidor and smaller fortified islands. For four days beginning February 14, destroyers from Squadrons 21 and 23 closed Corregidor’s cliffs to point-blank range so they could locate and silence guns hidden in caves. Fletcher and Hopewell were hit (Fletcher Water Tender Elmer Charles Bigelow posthumously received the Medal of Honor for sacrificing himself in fighting fires) that first day while La Vallette and Radford were also mined inside nearby Mariveles Harbor on the Bataan Peninsula.

On Valentine’s Day 1945, Hopewell received two hits from guns on Corregidor. Here in Manila Bay’s North Channel with the Bataan Peninsula in the background, she is still smoking less than three minutes after a hit on her forward stack. (NARA 80-G-305448)

The Sullivans was named for five brothers lost when cruiser Juneau was torpedoed after the battle of Guadalcanal in 1942. Here she screens Bunker Hill, which has just been hit by two suicide planes within 30 seconds on May 11, 1945. The Sullivans later picked up 166 members of the carrier’s crew when fire forced them overboard. (NARA 80-G-274264)

After the Lingayen operation concluded on January 17, the Seventh Fleet turned south to continue the liberation of the Philippines in an extended series of amphibious landings – at Palawan on February 28, at Zamboanga on Mindanao’s western tip on March 10, at Panay on the 18th, Cebu on the 26th, southern Mindanao on April 17, and finally at Borneo’s Tarakan Island, Brunei Bay, and Balikpapan on May 1, June 10, and July 1 respectively. Led by remnants of Squadrons 21–23 plus Hart, Metcalf, and Shields from DesDiv 116, each landing began with mine clearance and UDT operations. At Tarakan, Division 42’s last active ship was put out of the war – Jenkins, which struck a mine and came to rest with her bow on the bottom.

On January 26, Admirals Spruance and Mitscher relieved Admirals Halsey and McCain and the Third Fleet again became the Fifth Fleet. Before them lay the approaches to Japan. Iwo Jima in the Bonin Islands was valuable because the Japanese had constructed two airfields there and were working on a third. In Japanese hands, these posed a threat to Saipan; in American hands, they could provide an emergency landing strip for B-29 bombers returning to Saipan from Japan and a base for P-51 fighter cover. Okinawa in the Ryukyu Islands, within range of airfields on the southernmost Japanese island of Kyushu, was important as a staging base for the prospective invasion of Japan.

| Fletcher-class destroyer squadrons formed in late 1944 and 1945 | ||

| Squadron | Division | Ships |

| DesRon 571 | DesDiv 113 | Rowe,S Smalley, Stoddard, Watts, Wren |

| DesDiv 114 | Bearss,D Jarvis, John Hood, Porter | |

| DesRon 582 | DesDiv 115 | Colhoun, Gregory, Little, Rooks, Van ValkenburghS |

| DesDiv 116 | Hart, Metcalf, Shields, Wiley | |

| S Squadron flagship D Division flagship 1 Initially deployed to the Aleutian Islands 2 Never fully formed | ||

Unsung destroyer tenders were a vital part of the logistics chain. Here, six Sumners of DesRons 62 and 63 nest alongside Dixie in 1945: Compton, Ault, Charles S. Sperry, English, John W. Weeks, and Borie. (NARA 80-G-90541)

Operation Detachment, the seizure of Iwo Jima, was scheduled first because it was expected to be easier. When Admiral Turner’s Marines made the assault on February 19, however, they discovered that the Japanese had dug in more deeply than the preliminary bombardment could reach. It took a month of intense fighting to secure the island, during which shore batteries hit Leutze, Colhoun, and Terry, putting the latter out of action until the end of the war. Kamikaze attacks were not a factor.

Operation Iceberg, the invasion of Okinawa, was next. Preliminaries began on March 14, when Admiral Mitscher sortied from Ulithi to attack the Kyushu airfields. With him were 17 carriers, screened by 67 Fletchers and Sumners from DesRons 25, 47, 48, 52–54, 61, and 62.

On March 19, carrier Franklin was hit by two bombs. Her 832 dead and more than 1000 total casualties might have been even worse had not DesRon 52’s Miller and Hickox taken off personnel and helped fight fires from close aboard. The following day, Halsey Powell was alongside carrier Hancock when a suicide plane overshot the carrier and crashed into her stern, sending her home for repairs.

Class leader of the minelayers, Robert H. Smith, with her mines visible amidships on tracks that lead over her stern. (NARA 80-G-237956)

“So good that we cannot spare them,” said Admiral Turner of Heywood L. Edwards and Richard P. Leary, both of which were repeatedly commended for their accurate and devastating fire through six Pacific operations. Leary, shown here, became DesRon 56 flagship in April 1945 after Newcomb was disabled. (NARA 80-G-237956)

| Robert H. Smith-class destroyer-minelayer squadron formed in 1945 | ||

| Squadron | Division | Ships |

| MinRon 3 | MinDiv 7 | Harry F. Bauer, Robert H. Smith, Shannon, Thomas E. Fraser |

| MinDiv 8 | Adams, Henry A. Wiley, Shea, Tolman | |

| MinDiv 9 | Aaron Ward, Gwin,S J. William Ditter, Lindsey | |

| S Squadron flagship | ||

Next, Vice Admiral Turner stood out for Okinawa with more than 1,200 ships in his Expeditionary Force – among them ninety-six 2,100- and 2,200-tonners from DesRons 24, 45, 46, 49–51, 55–58, 60, and 66 and the 12 converted Sumners of Mine Squadron 3.

A first step on March 26 was the seizure of the Kerama Retto (Kerama Islands) 20 miles west of Okinawa as a forward anchorage. MinRon 3 led 75 sweepers in clearing 3,000 square miles of ocean. Except for Halligan, which was mined on March 26, subsequent mine losses were negligible. That same day, however, Kimberly was damaged by kamikazes as was O’Brien the next day – her second kamikaze strike of the war.

On April 1, 23 destroyers provided fire support as the first of nearly 200,000 United States troops landed at Hagushi on the island’s west side. As at Peleliu and Iwo Jima, the Japanese did not contest the beaches but defended in depth inland to inflict maximum losses. Over the next 82 days, they sustained an estimated 250,000 army and civilian casualties.

Offshore, Admiral Turner reassigned DesRon 63’s Commodore Frederick Moosbrugger to take charge of the destroyers as ComTaskFlotilla 5. To prepare for sustained air attack, Moosbrugger deployed them in three lines of defense. As his front line, he established eight (later nine) radar picket stations 40 to 70 miles distant from the transport area. These he backed up by outer and inner anti-air, anti-small boat, and anti-submarine screens within 25 miles of the beachhead to protect the anchorage and ship movements between Okinawa and Kerama Retto.

Newcomb shortly after being struck off the small island of Ie Shima during the first mass kamikaze attack at Okinawa, April 6, 1945. Here, minus her after stack, she staggers out from under a pillar of smoke. (NARA 80-G-322419)

The distant radar pickets were key: the Okinawa defense depended on their rapid reporting of incoming attacks and fighter direction. Initially, each consisted of one Fletcher or Sumner, with a team of two fighter directors plus radar- and radiomen embarked, to report enemy plane contacts and vector out combat air patrols (CAP) to intercept. In defense, each picket station was assigned its own CAP of four to six planes, with which it communicated on a separate frequency. It also had two landing-craft support vessels, which were stationed one-third of the distance to the neighboring radar picket stations to increase the probability of detecting low-flying planes or other surface threats. For the destroyers, close-in self-defense meant maneuvering at 25 knots or more and presenting one’s broadside to an attacking plane to provide both the greatest concentration of gunfire and the shallowest possible target.

What damage a single kamikaze could do: Leutze was lying alongside Newcomb when one more plane approached. With Newcomb’s superstructure masking her guns, she could not defend herself. The plane caught Newcomb’s fantail and then slammed into Leutze, nearly severing her stern. Neither ship was repaired after returning home. (NH 69110)

Thanks to Admiral Mitscher’s strikes on Kyushu in March, all was quiet until April 6. That day, however, accompanying the suicide sortie of the battleship Yamato, the first mass attack came in – a kikusui (“floating chrysanthemum”) of 376 kamikaze suicide planes and 341 other planes, which hit 18 ships including 12 destroyers. Bush and Colhoun were sunk; DesRon 56 flagship Newcomb and sister Leutze were hit so hard that they were repaired only sufficiently to get them home; Mullany, abandoned and then reboarded, made Kerama Retto under her own power. Haynsworth, Hyman, and Howorth also sustained casualties. In response, on April 10, Captain Moosbrugger increased the number of pickets on each station to two destroyers and pulled in the support craft, now grimly known as “pall bearers,” to operate within 3,000 yards.

A new horror appeared on April 12: the Okha, a short-range, rocket-powered missile with plywood wings carrying 2,600 lb of explosives, dropped by a mother plane, and guided to its target at 500 miles per hour by a human pilot. One hit Mannert L. Abele amid the chaos following a conventional kamikaze hit, sinking her in three minutes. Others struck Purdy and Cassin Young and glanced off Stanly that same day.

In addition to single and small group attacks that could appear at any time around the clock, nine more kikusuis followed. Some engagements lasted more than an hour. Casualties of more than 20 percent were sustained by Kidd on April 11; Lindsey and Zellars on the 12th; Sigsbee on the 14th; Laffey, Bryant, and Pringle on the 16th; Isherwood on the 22nd, and Hazelwood and Haggard on the 29th. DesRon 24 flagship Hutchins was blasted by a suicide boat on the 27th. Losses peaked again on May 3–4 when Little, Morrison, and Luce were sunk – the second two with more than 500 dead between them – and Aaron Ward, Gwin, Shea and Ingraham were badly damaged. The great fight of Evans and Hugh W. Hadley followed on the 11th (see Plate E) and Bache was mauled on the 13th.

In mid-May, US airstrips and radar stations became operational on Okinawa and soon land-based fighters were joining bombers over Japan. The number of active picket stations was reduced to five, with at least three destroyers assigned to each. Losses continued, however: Longshaw was sunk on the 18th with more than 50 percent casualties; Thatcher was critically damaged on the 20th; and on the 27th, the day that Halsey relieved Spruance and the Fifth Fleet became the Third Fleet again, Braine sustained 144 casualties. The next day Drexler lost 60 percent of her crew, with the dead outnumbering the wounded by three to one. On June 6, the day after another typhoon passed by, J. William Ditter was damaged beyond repair while on the 10th, William D. Porter succumbed to a near miss that opened up her seams. On the 16th, Twiggs was lost with 214 casualties. The Army declared Okinawa secure on June 21 but the pickets’ finale came only on July 29, when Prichett was hit and Callaghan sunk, and on the 30th, when Cassin Young was hit for the second time.

On May 3, 1945, in her second major anti-kamikaze action, minelayer Aaron Ward was nearly razed and set afire by direct hits from five kamikazes and a glancing blow from a sixth. Towed to Kerama Retto after a night-long battle to remain afloat, as seen in this May 13 photo, she was made seaworthy and steamed home to New York under her own power but was not repaired following the war. She received the Presidential Unit Citation for this action. (NARA)

Her forward-bearing firepower is evident as 2,200-tonner Purdy runs trials off Cape Elizabeth, Maine on July 18, 1944. Purdy received a Navy Unit Commendation for action on April 12, 1945 when, in a 90-minute battle, she was struck only by the last of about 30 attacking planes. (NARA 80-G-235680)

Outstanding performances were everywhere. Bennion excelled in fighter direction; Wadsworth survived 22 attacks during 36 consecutive days on station; Barton set an endurance record of 87 continuous days without damage. But 77 Fletchers and Sumners were hit: 63 of those that had deployed with Turner; 17 with Mitscher. Thirteen of the former were sunk; the others limped or were towed to the Kerama Retto anchorage, where still they were not safe: there was always a fear that suicide swimmers might board and overwhelm unarmed crews repairing hulks “in cold iron” during the weeks it took to make them seaworthy. Yet none were scrapped or abandoned: all 64 made it home – under their own power or towed – where only nine were judged unworthy of repair.

Of the more than 58,000 men at sea in these 175 ships, nearly 2,200 were killed and 2,600 wounded – an overall casualty rate of about 8 percent but about 20 percent for those hit. Seven Fletchers and Sumners lost more than 50 percent of their crews. Five sustained more than 150 casualties with more than 100 killed – 60 to 80 percent of total casualties in each case: Halligan, which drifted aground under enemy guns; Morrison and Drexler, which sank so quickly that men below decks could not get out; Luce, which had a power failure; and Twiggs, which was torpedoed in a magazine and then was crashed. Pringle and Longshaw also sustained more than 150 total casualties. Twelve other ships suffered more killed than wounded; Braine and Hazelwood recorded the highest casualties of those not sunk.

For every survivor, such statistics mirrored sights of scores of aircraft swarming overhead; of the fearless Corsair pilots of the CAP; of enemy planes bursting into gigantic fireballs or, conversely, closing untouched, in seeming slow motion, to point-blank range; of hearing impaired for life by the shattering sound of 5-inch fire; of whole sections of a ship demolished in an instant, leaving only mangled and scorched survivors, if any; of damage-control parties working frantically to stem flooding; of a pharmacist’s mate performing triage; of piled-up body parts and blood running down the decks; and of unanswered calls to muster – all condensed to terse citations that characterized their performances as having been “in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

Few at home ever learned what the destroyermen endured at Okinawa. At the time, other events obscured their exploits: President Roosevelt’s death; Allied victory in Europe; the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki; and finally the Japanese surrender with press coverage focusing on General MacArthur. After the war, their tales merged with others of the war or were never told – so much seemed beyond description or best forgotten. But observers were unrestrained in tribute.

|

1) USS DE HAVEN (DD 727), 1944 De Haven, flagship of Destroyer Squadron 61, is shown in camouflage Measure 32/3D, which she shared with Sumner-class sisters Ingraham, Cooper, English, Walke, Laffey, O’Brien, Meredith, Mansfield, Hyman, Shannon, Adams, Brush, and J. William Ditter. An excellent model of De Haven by Gibbs & Cox is in the possession of the Maine Maritime Museum at Bath, where De Haven was built. |

| 2) USS ROBERT H. SMITH (DM 23), 1945 Lead ship of a class of twelve 2,200-ton destroyers converted as high-speed minelayers, Robert H. Smith appears here in Measure 32/25D. As Mine Squadron 3, the 12 went to Okinawa, where eight were decorated. Smith received the Navy Unit Commendation for her outstanding record in mine clearance operations and as a fighter direction ship, March–June 1945. |

In a heavy weather scene familiar to any destroyerman, Isherwood comes alongside heavy cruiser Tuscaloosa in August 1943. (NARA 80-G-79429)

“These picket ships ... fought and won the longest and hardest battle in the history of naval warfare,” wrote New York Times correspondent W. H. Lawrence. “They suffered the greatest losses in men and ships ever sustained by the United States Navy, but they fulfilled their mission of keeping the bulk of the enemy aircraft out of the transport area.”

“Never ... have naval forces done so much with so little against such odds for so long a period,” added Captain Moosbrugger in his action report. And from afar, Prime Minister Churchill registered his overall verdict in a postwar message to President Truman: “The strength of willpower, devotion and technical resources applied by the United States to this task, joined with the death struggle of the enemy ... places this battle among the most intense and famous of military history.”

On July 1, Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet – now incorporating elements of the Seventh Fleet and the Royal Navy plus the first Gearing-class radar pickets – commenced launching air strikes to soften up Japan for invasion. On July 18–19, DesRon 62 with Cruiser Division 18 swept Sagami Wan outside Tokyo Bay. On July 22–23, in rough weather following the passage of a typhoon, DesRon 61 attacked a convoy in the same area. On July 29–30, DesRon 48, Southerland and three British destroyers screened a battleship and cruiser formation in shelling factories in southern Honshu; and on 30–31, DesRon 25 brazenly penetrated all the way to the head of Suruga Wan near Mt. Fuji to deliver another shelling. Then, on August 6, a B-29 from Tinian dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. On the 9th, the day a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, Borie became the last destroyer hit by suicide aircraft.

Chevalier was one of five Gearings to earn a campaign medal in World War II. Here she steams in the Atlantic on May 24, 1945, ready to transfer to the Pacific after her conversion as a radar picket. (NARA 19-N-38596)

There was rejoicing on August 15 when the news of the ceasefire arrived but it took nearly two weeks to organize minesweeping operations and occupation events. Finally, on August 27, the Third Fleet, with the 2,100- and 2,200-tonners of Squadrons 21, 25, 48, 50, 53, 57, 60, 61, and 62 and long-hulls Benner, Chevalier, Duncan, Frank Knox, Hawkins, Higbee, Myles C. Fox, Perkins, Rogers, and Southerland attached, closed the Honshu coast and anchored in Sagami Wan. From there, on the 28th, Southerland and DesDiv 106 led cruiser San Diego and auxiliaries into Tokyo Bay to secure the Yokosuka Naval Base and begin liberating prisoners of war. The fleet followed on the 29th, and on September 2 Nicholas and Taylor ferried Allied representatives and members of the press to the battleship Missouri out in Tokyo Bay for the formal surrender.

Over the next months, destroyers from across the Pacific returned home. Some arrived in time to receive visitors on Navy Day, October 27; most returned by the end of the year. No homecoming was more celebrated than that of DesRon 23’s Charles Ausburne, Claxton, Dyson, and Converse, which steamed up the Potomac River to the Washington Navy Yard on October 17. Two days later they received a group Presidential Unit Citation in a ceremony attended by Admirals Halsey and Mitscher and, of course, Captain “31-knot” Burke.

Under way for Tokyo Bay: Twining and Wedderburn stand out of Sagami Wan on August 28, 1945 for the occupation of the Yokosuka Naval Base. View looks west with Mt. Fuji in the background. (NARA 80-G-344505)