The Main Character in Leading Meaningful Change Is You: Use-of-Self in the Change Process

The Main Character in Leading Meaningful Change Is You: Use-of-Self in the Change Process The Main Character in Leading Meaningful Change Is You: Use-of-Self in the Change Process

The Main Character in Leading Meaningful Change Is You: Use-of-Self in the Change ProcessIn the late 1990s, coaching was just starting to surface as a support for leadership development, and in some cases was even formalized inside organizations. Working with my mentor and colleague Edith Whitfield Seashore, we developed a coaching model we called Triple Impact Coaching (TIC) and spelled it out in our book Triple Impact Coaching: Use-of-Self in the Coaching Process (2006). Our model was originally designed for a specific group of research and development managers who were leading the integration of two teams—product support and new product introduction—into one. Our TIC model was successful and has since been adapted and used globally with leaders and managers in all types and sizes of businesses and industries in the public, private, and plural sectors (the last comprising our communities, charities, not-for-profits, clubs, etc.).

At the core of the TIC model is the concept called Use-of-Self. This concept continues to sit at the core of the new LMC Framework that this book presents. It forms the foundation for the seven guiding principles of the LMC Framework that you will learn about in chapter 3. You may be familiar with it already from prior workshops you have taken or articles you have read—or it may be brand new to you. Whatever your background with it, it is worthwhile reading this chapter closely, as the Use-of-Self model I present here has evolved since the publication of our book and has been enhanced with research and examples that reflect the current trends and challenges we face in our workplaces and our world.

My introduction to Use-of-Self goes back to the work and teachings of two luminaries in the field of organizational development, the late Dr. Charles Seashore and his wife, Edith Whitfield Seashore (Charlie and Edie, as they liked to be called). I met Charlie in 1995 when he taught in the Master of Applied Social Science program (now called Applied Human Sciences) at Concordia University in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. At the time, this was a new Master of Arts program in organizational development, modeled after American University’s Master of Science in Organizational Development, where both Charlie and Edie also taught.

I was a student in the first graduating cohort. In that program, we were provided with a unique opportunity to select one elective course for our second year. One day over lunch, Charlie talked about Edie’s course, “Use-of-Self as Instrument,” which sounded interesting, so I chose it as my elective. This course changed my life, as it did for many others in our class. Edie and I connected right away and developed a relationship that flourished. She became not just my teacher but my mentor, coach, business partner, and close friend.

In 2000, Edie agreed to work with one of my client organizations, where I had been hired to deliver a coaching program to develop leaders and teams to lead and manage change. When we got together to do the teaching handover, I presented Edie with a binder of materials I had created for this client. She read them over and encouraged me to write a book about the TIC concept and the Use-of-Self. I agreed, but only on the condition that we author it together. This was the start of a mutually rewarding and long friendship that lasted until her death in 2013. In addition to teaching together at McGill University and working with our clients in Canada, we published our book, which continues to influence many coaching programs throughout the world and is the foundation for my coaching and organizational development practice and research today.

What exactly is Use-of-Self? What did the Seashores mean by it? In a special edition of the Organizational Development Journal, their daughters, Becky May and Kim Seashore, wrote:

Our parents exemplified the integration of Use-of-Self beyond the buzzword, beyond a concept that needed to be isolated or highlighted, beyond a tool exclusively of or for the trade of (OD). One of our mother’s favorite sayings was: “A master in the art of living draws no sharp distinction between his work and his play, his labor and his leisure, his mind and his body, his education and his recreation. He hardly knows which is which. He simply pursues his vision of excellence through whatever he is doing and leaves others to determine whether he is working or playing. To himself he always seems to be doing both. Enough for him that he does it well.”1

Edie and Charlie lived this motto and philosophy of the integrated self. They may not have created the phrase or concept “Use-of-Self,” but they now have a legacy that lives on.2

Another passage that Charlie wrote in the foreword of Triple Impact Coaching sums up superbly the meaning of Use-of-Self:

The focus of Triple Impact Coaching is Use-of-Self. It is simple, profound and infinitely complex—all at the same time.… We know the value of instruments and tools of the trade in all of our various professions. We also know that there is a temptation to attribute the success of our work to the technical tools or strategies that we use and the accompanying belief that all we need to do to increase our range of effectiveness is to acquire more of these tools.

The simple theme to pay the most attention to is the person using the tools, meaning oneself, rather than focusing on the design of the tool. An excellent tool in the hands of a struggling professional can do great damage while an imperfect tool in the hands of a true craftsperson can morph into an awesome impact at individual, team and organizational levels.3

Charlie elaborated on the deeper philosophy and psychology embedded in Use-of-Self as a core leadership tool in an article he later published with colleagues, entitled “Doing Good by Knowing Who You Are: The Instrumental Self as an Agent of Change”:

Use-of-Self is a link between our personal potential and the world of change. It starts with our understanding of who we are, our conscious perception of our Self, commonly called the ego, and the unconscious or out of awareness part of our Self that is always along for the ride, and on many occasions is actually the driver. This understanding of Self is then linked with our perceptions of what is needed in the world around us and our choice of a strategy, and a role in which to use our energy to create change. Our focus here is on the potential for changing one’s own world—the world as we perceive it, and to act on it and leave our mark and legacy for others to appreciate.4

In their article “Use-of-Self: Presence with the Power to Transform Systems,” Mary Ann Rainey and Brenda B. Jones, both colleagues of the Seashores, expanded on the Use-of-Self concept as it applies to change agents described as leaders, managers, consultants, and professionals at the forefront of change. They state that transformational change begins with the change agent through a process that involves understanding self, thoughtful Use-of-Self, and engaging with a presence that motivates, inspires, and engenders followership. They believe that when these agents of change transform their capabilities, including their emotional intelligence, they also transform the capabilities of the system in which they live and work. They developed the framework shown in Table 1 to help analyze the self in a matrix of four dimensions: self-awareness, self-concept, self-esteem, and social-self.5

Table 1 Four Elements of Self as Perceived by Mary Ann Rainey and Brenda B. Jones

|

Self-Awareness Level of knowledge about self (e.g., values, biases, tendencies, culture, and the extent that knowledge is applied consistently in everyday life). Extent to which I am self-aware. |

Self-Concept Self-perception. The broader collection of assumptions and beliefs one holds about one’s self. Who am I to me? Three words I use to describe me. |

|

Self-Esteem Value placed on one’s self-concept. Overall evaluation and judgment of one’s worth, usually viewed against one’s judgment of others. My level of self-esteem. |

Social-Self Relatability. Awareness of and healthy interaction with others. Ability to establish and manage quality relationships. How I rate my social-self. |

This chapter is largely about Use-of-Self as it pertains to coaching. It also plays a role in mentoring situations, though other factors are also required. For clarity, here is the distinction I make between coaching and mentoring. While I believe all leaders have a responsibility to coach and develop people to be effective in their roles, not all leaders mentor. Table 2 shows how the two differ.

Some organizations use a hybrid or blended model that combines both coaching and mentoring. But for purposes of LMC, keep these distinctions in mind as we discuss coaching and mentoring.

Table 2 Coaching versus Mentoring

| Coaching | Mentoring |

| Short-term development | Long-term development |

| Performance-driven: Setting goals, taking action, monitoring, evaluating, and sustaining change over time | Vision-driven: Exchanging wisdom, support, learning, and guidance to achieve vision, purpose, and strategic priorities |

| Technical or professional focus: Role, function, or service | Political, professional, and/or technical focus: Guidance on navigating the organizational context, people, networks, and community |

| Professional relationship between coach and employee: Usually formal | Privileged relationship between mentor and mentee: Can be formal or informal |

| Inspires respect for competence: Skills, knowledge, and expertise | Is a role model: Values, beliefs, mindset, and behaviors |

Based on these roots, you can see that Use-of-Self goes beyond just self-awareness to being a fully integrated way of living and being. It is a mindset, philosophy, and process that needs to be attended to and developed throughout the change and transformation process. In this context of change, Use-of-Self can be challenging, as you may be leading and managing others while you, yourself, are going through change and uncertainty. For these reasons, the Use-of-Self remains the core concept in the LMC Framework just as it was in the TIC model.

Our Use-of-Self is in constant play in many situations in organizational learning and development. As leaders and change agents, we coach and mentor others and we are often coached and mentored ourselves. I believe coaching and mentoring are essential skills and provide valuable support for development, especially when we take on, transition to, or prepare for new roles, assignments, or opportunities. Use-of-Self therefore is essential for supporting the growing trends of multiple generations of employees working together in one workplace, the increase need for reverse coaching and upward mentoring whereby the younger generation coaches and mentors their more senior colleagues.

Use-of-Self also applies when we learn new processes and technologies. It is especially important when we need to develop skills to navigate the political networks within and outside of the organization.

When Edie and I first published our book Triple Impact Coaching, we devised the diagram shown in Figure 1 to visualize the process implied in the term “Triple Impact Coaching.” The diagram pictures a series of concentric circles reflecting the three layers that make up organizations: individuals, teams, and the entire organization. At the center of the diagram is a bifurcated circle, with “Aware” on one side and “Unaware” on the other. A needle called “Self” cuts across the dial, suggesting how Use-of-Self turns the consciousness of each person and layer of the organization from being unaware to being aware. At the left side are the four keys—choices, reframing, power, and feedback—necessary to master and turn the needle.

Our thinking was that the greater the awareness and efficacy of each leader’s Use-of-Self, the more informed, intentional, and conscious individuals, teams, and the entire organization will be about the choices they make in their approach to achieving the desired performance. As one moves toward awareness, it has an impact on one’s team, and then on the organization. Individual, team, organization: hence the name Triple Impact Coaching.

One of the global thought leaders in the field of management, Dr. Henry Mintzberg, Cleghorn Professor at McGill University, redefined the role of the manager in his book Managing. He describes the manager as someone who manages on three planes: through information, with people, and for action (Figure 2).6

This model shows the manager sitting in the middle, between the unit they manage and the world outside—the rest of the organization as well as what is around the organization. Two roles for a manager exist on each plane. On the information plane, managers communicate (all around) and control (inside). On the people plane, they lead (inside) and link (to the outside). On the action plane, managers do or act (inside) and deal (with the outside). Managers work on all three planes to frame (conceive strategies, establish priorities) and schedule work (including their own time).

Figure 1 The Original TIC Model

Figure 2 Mintzberg Model of Managing

Mintzberg states that the overriding purpose of managing is to ensure that the unit serves its basic purpose, whether it is to sell products in a retail chain, care for the elderly in a nursing home, or whatever it may be. This requires taking action by coaching, motivating, building teams, strengthening culture, and other key steps. To do this, managers use information to coach other people to take action, such as setting a target for a sales team, sharing information about a customer, etc.

For Mintzberg, coaching thus plays a critical role in the development and effectiveness of leaders and managers. They must learn how to coach others, but equally important, they must learn how to be coached themselves for success. Accordingly, it is impossible to look at the interplay of leadership and coaching without reflecting on the Use-of-Self and vice versa. Coaching is an integral role of leading and managing in the workplace and is an essential skill for everyone in the organization.

Since the publication of Triple Impact Coaching, I have been using the model in my consulting work with scores of organizations to help them achieve meaningful change. Throughout the course of this book, you will read about several of these organizations and how they implemented the elements of Use-of-Self across their entire leadership and management teams to achieve triple impact. My clients tell me that when they pay attention to their Use-of-Self, they are more self-aware, intentional, and authentic in how they are and want to be “showing up” in their relationships at work, at home, as members of their communities, and on this planet. When they trust themselves, they are able to trust others, which leads to better ways of working with people and faster paths to reaching common ground, collaborating as teams, and achieving their desired organizational goals. When the Use-of-Self mindset, principles, and practices are applied, leaders report achievements that are far greater than their single contribution.

Before I review the skills that help leaders and managers learn and master Use-of-Self, I want to stress that my original concepts of Use-of-Self have evolved over the past decade. No model in organizational development can remain static in this fast-changing world. Since our book was first published in 2006, technology especially has transformed the way we live, work, and play. When TIC was developed, we were still storing data on floppy disks and flash drives, and using iPods and DVDs to listen to our music and watch videos and movies. Most of us had BlackBerries, Motorola flip phones, and desktop computers. Today, people are plugged-in all the time and have instant access to data and information. Instead of six degrees of separation, we are only one click away from any individual, group, or society.

Add to this the fact that in most organizations, multiple generations are working together and whose education, values, experiences, and instincts are far different than the baby boomers who occupied most senior positions in the early 2000s. In many organizations, millennials are now the managers, if not senior leaders, as boomers retire. Those boomers who are still working are not always the most technologically savvy.

As a result of these transformational changes, it is no surprise that the application of Use-of-Self had to change. On the technology side, the skills that leaders need to have must extend beyond face-to-face interactions. Managers and leaders need to consider how to show up online, on social media platforms, through email, and on any other digital media we use to communicate and work with others. They must understand how to lead and coach a highly diverse workforce, composed of people from many cultures, often international, with differing backgrounds, values, and understandings of the way the world works. The pressure to achieve and succeed in a global world adds complexity to many change efforts, as competitors and disrupters work hard to overthrow the existing leaders in every industry.

To better understand how Use-of-Self needed to evolve, I conducted three studies in the past few years:

From these studies, I drew numerous conclusions that have helped me evolve how leaders and managers develop the skills that will lead them to master their Use-of-Self. The former four keys to Use-of-Self have now become six keys. Here’s a review of those studies to provide context for what you will learn as you go through this chapter.

This study involved a review of change leadership challenge projects from approximately 2,000 participants in 27 countries and representing all organizational levels (including managers, directors, senior leaders, and project team members) from private, public, and plural sector organizations. As prework, these study participants completed the Change Leadership Challenge Exercise before attending custom client workshops and programs on leading change and transformation at McGill University, Queen’s University, Concordia University, and the University of Notre Dame.

The exercise was their initial assessment of a change project they were working on in their organizations. They also had to identify any hot topics that needed to be addressed during the program. Their projects focused mainly on wanting to learn how to lead a change effort, such as an organizational culture shift, a large-scale organization-wide project or initiative, a merger or acquisition, or the design and implementation of new processes, technologies, products, and services in their organizations. The participants came from different organizations and geographies around the world. A review of their responses found some clear trends in the change leadership competencies they wanted to improve, with top priorities being creating alignment, building strong and cohesive teams, managing resistance and culture shifts, and learning change management methods and tools. Especially notable in their comments was a shift in their focus from the technical and structural processes and systems to concerns about leading and improving the performance of their teams.

Taken together, these comments showed that participants recognized that a dysfunctional individual or team could negatively impact the change process. Thus, activities in creating alignment on a shared purpose and priorities, leading and managing the shifts in the organization’s culture, and developing effective teams were essential to them.

This study revealed to me an opportunity to make the work of change that one does in TIC more meaningful and sustainable. The TIC model needed to heighten how it aligns and integrates with real work, rather than as an add-on. Teamwork and organizational culture had to be priorities and worked on throughout any development or change process. Through this study, it was also apparent that regardless of one’s role or the size and complexity of the change, it is critical to have both change leadership and change management to succeed.

This study involved a series of formal conversations I had with colleagues and multigenerational leaders. These people had learned about TIC from my and Edie’s book or from workshops or courses they had taken with Edie, me, or others. Participants in the study confirmed that their Use-of-Self was invaluable in their life and work. They described Use-of-Self as a “lens” that helps them see and understand themselves so they can be more aware of their intentions, choices, and the impact they want to have on others.

Using the actual words this group commonly cited to me about Use-of-Self, I constructed a graphic (Figure 3) in the shape of eyeglasses, symbolic of this lens idea. Paradoxically, when I showed some other people this image, they saw in it a pair of handcuffs that, for them, represented how we can often get locked in our own perspectives, stories, and biases that disable, block, or distort our ability to be our “best self.” Lastly, this image also represents the infinity symbol, illustrating the Use-of-Self as a complex lifelong journey or the multiplier effect that we can have when leading meaningful change. All three interpretations work.

Figure 3 Word Cloud Based on Survey of Individuals Responding to What Use-of-Self Means to Them

This study revealed that TIC and Use-of-Self needed to move beyond a performance model focused on the individual, team, and organization to become a more continuous, dynamic, and integrated process, which led to the Leading Meaningful Change study.

This study included a series of interviews and working sessions with the senior leadership team at the City of Ottawa, where I was working as a consultant helping with the city’s transition to a new organizational structure as part of a larger transformation journey. This work took place over two and a half years. The team identified the following key elements as important:

This study helped me evolve the guiding principles of the LMC Framework beyond the foundational ideas of TIC.

The results of these three studies, as well as my teaching and consulting work over the last decade, helped me identify several main themes that have driven an effort to evolve TIC into the broader LMC Framework that you will read about in the remainder of this book.

While TIC was not designed as a study on demographics, it became clear that a new framework had to be more explicit in recognizing that the Use-of-Self is a crucial skill to master regardless of one’s generation, gender, stage of life, or career field. Use-of-Self is a lifelong learning process and can be applied to all aspects of our lives. It may seem complex and challenging to develop and manage given the fast-paced, turbulent, and constantly changing world that we live and work in, but it is worth mastering.

TIC was not written with radical change in mind, but it is now clear that the only constant in modern life is change. A new framework had to incorporate the dynamic of change as inevitable. Nevertheless, regardless of all the changes and complexities we face in our lives, people still want to live their best selves. In the midst of the storm, we still have a choice in what we think, how we feel, and the actions we take to respond and be accountable. The LMC Framework had to help people master Use-of-Self as the only constant they could rely on.

The original TIC model was focused on creating and sustaining alignment on a common vision and strategic goals, and evaluating the performance and the actions of the individual and team to advance the organization, thus the triple impact that I defined earlier. In a new model, Use-of-Self can still be focused on these three levels, but it had to go beyond to include the impact of one’s work on the community and planet. Growing sensitivity to our universal connectedness and the need to preserve the planet we live on has increased our need for meaningful relationships and work. People today want to belong to an organization that they respect and that demonstrates in its actions the values they share. They want to be part of and work in an organizational culture that fosters health and wellness, contributes positively to their communities, and makes a difference in the daily life of all stakeholders. They also want to be part of a positive movement that results in something meaningful and larger than themselves, and one that does not ruin the planet but sustains it for future generations.

As stated above, TIC was not written with the astonishing advances in technology in mind. But it is inarguable that technology has transformed the worlds of work and personal life over the past decade and will continue to evolve and present new opportunities through innovation, automation, and planned and disruptive change. The pace of change has accelerated, and with it comes a continuous process of learning and development. Use-of-Self thus requires us to create space for learning and experimenting so that we can become more self-aware of how to adapt to the changes that technology brings.

Technology also plays a new role in how we all communicate in today’s world, which has grown to be even more challenging given the pervasiveness of social media, shorter news cycles, and the volume of immediate and easily accessible information, both real and fake. Use-of-Self in this new world must integrate developing strategies to be agile, reduce resistance, build trusting and effective relationships, work with excessive amounts of data, and yet still communicate clearly.

Technology can be used to help or harm. We have a choice in how we use it. Technology provides real-time, instantaneous access to information and data that can inform our decisions, connect us with people and our communities, and enable us to conduct our businesses. Sometimes we must make choices and decisions in nanoseconds. We know immediately if we are liked, disliked, or are polarizing. We have access to information that lets us know how we are doing individually and as an organization. Social media can also be used to test assumptions, provide ideas, and receive feedback in real time.

In a new framework, the reliance on technology and the impact of the digital world present new developmental opportunities for all of us. We need to be conscious of how we choose to use technology. We also need to cut out the noise, eliminate fake news, and focus on validity and facts by working with sound, current data.

All generations in the three studies expressed concern about the influence of technology in their Use-of-Self. People want to seek meaningful relationships and connections, yet the increasing use and abuse of technology make that difficult. With cyberbullying and threats to our personal well-being and security, people must be intentional about setting personal and professional boundaries. They must also protect their psychological safety when they show up online and use social media. They must decide who they want to follow and who they want to influence—or not.

Gen Zs also told us that they learn social skills online that previous generations learned via face-to-face interactions and in small groups. The new generation’s learning is often public, not private, and can be negative, which leads to depression, anxiety, and social isolation. This suggests that we need to learn new ways to develop our social skills in the virtual world.

Participants in our interviews also said that they often experience the impact of an uneven distribution of power and an erosion of ethical behavior within their organizations and on the world stage. Balancing the expectations of the individual and the collective, as well as the broader stakeholder groups within the larger global context, is more challenging today than in the past. Participants thus suggested that a new model must help define new governance models and clarify roles and relationships that are more equitable, fluid, and interdependent. Their feedback also suggested a growing need to learn how Use-of-Self can help create alignment and build effective working relationships even within complex political partnerships and stakeholder groups. This new challenge requires active visible leadership, cross-collaboration, and teamwork.

The TIC model focused on teamwork and helping leaders apply participative, collaborative processes to build multidisciplinary teams and to work across the organization. This emphasis is still relevant in the new LMC model, but it needed to extend to working in networks both within and outside of our organizations, such as with partners and other stakeholders.

The previous model of Use-of-Self was about performance at work. For some leaders and highly driven organizations, there was no work/life balance. But today’s employees are focused on health and wellness and do not want to burn the candle at both ends. A new need to focus on the whole person is critical in leading meaningful change. Aligning personal purpose with one’s role and the organization’s purpose is essential. This includes prioritizing and balancing life, work, health, time, and resources when developing Use-of-Self strategies to lead meaningful change.

The new model of Use-of-Self in the LMC Framework thus builds on these themes and the feedback from participants in this research. The new model depicts a process of continuous movement and incorporates the current world context and emerging trends, such as the importance of ethics and building trust in organizations, the impact and influences of technology, sociocultural and economic changes, geopolitical influences, social justice issues, our global and local concepts of community, and our desire for a sustainable planet. The Use-of-Self foundation and principles are now also aligned with the current research on emotional intelligence, neuroscience, and mindfulness.

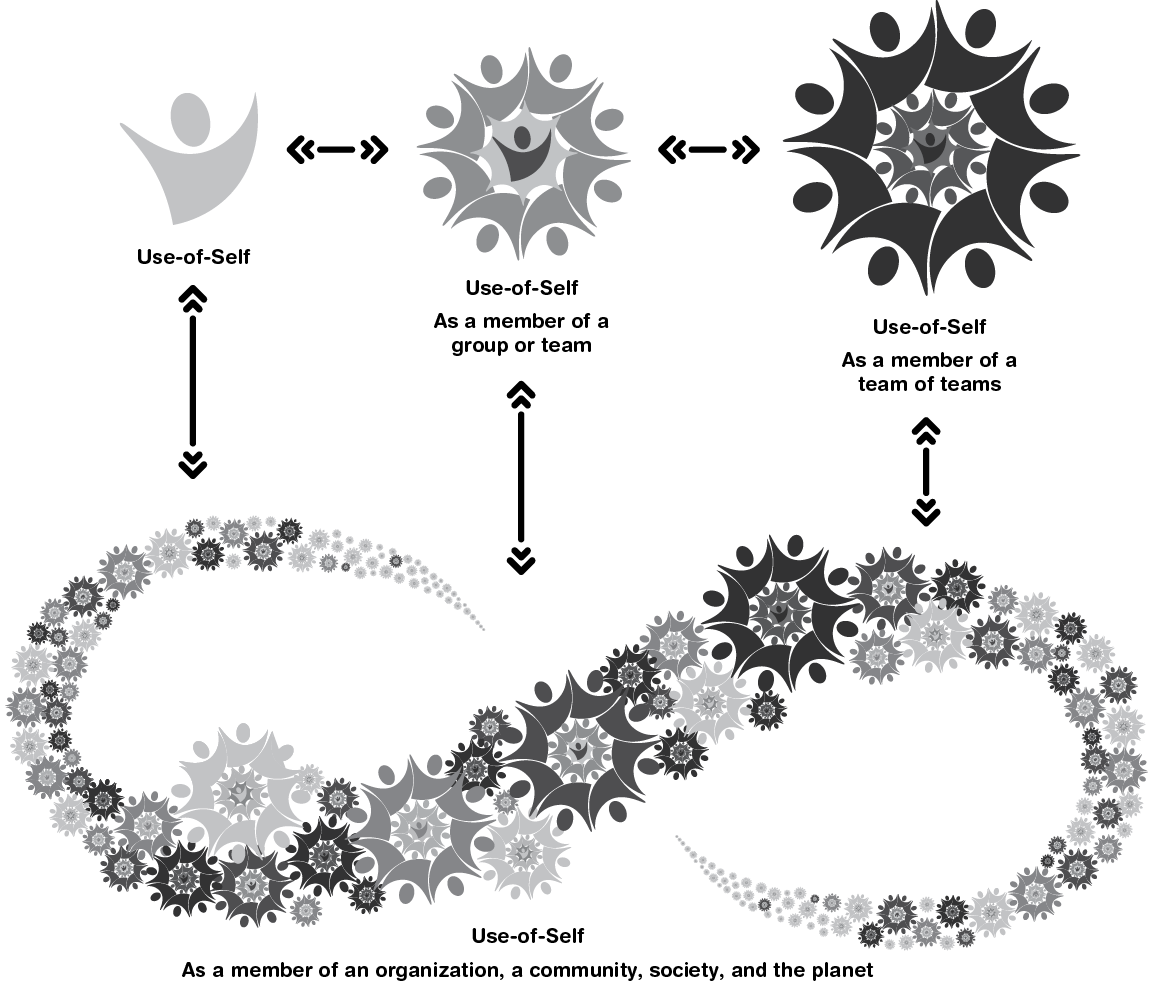

Figure 4 depicts a new visual representation of the LMC Framework and Use-of-Self that replaces the former TIC diagram you saw in Figure 1. As you can see, this model considers the Use-of-Self in a variety of contexts—individual, team, team of teams, organization, community, society, and planet. It combines them into a dynamic, flowing wave in the form of an infinity symbol, suggesting the never-ending challenges of change, the constant Use-of-Self, and the multiplier effect that can happen on all levels.

Figure 4 The New LMC Framework and Use-of-Self