CHAPTER 1

Darwin’s Really Dangerous Idea

Adaptation by natural selection is among the most successful and influential ideas in the history of science, and rightly so. It unifies the entire field of biology and has had a profound influence on many other disciplines, including anthropology, psychology, economics, sociology, and even the humanities. The singular genius behind the theory of natural selection, Charles Darwin, is at least as famous as his most famous idea.

You might think that my contrarian view of the limited power of adaptation by natural selection would mean that I am “over” Darwin, that I am ready to denigrate the cultural/scientific personality cult that surrounds Darwin’s legacy. Quite to the contrary. I hope to celebrate that legacy but also to transform the popular understanding of it by shedding new light on Darwinian ideas that have been neglected, distorted, ignored, and almost forgotten for nearly a century and a half. It’s not that I’m interested in doing a Talmudic-style investigation of Darwin’s every word; rather, my focus is on the science of today, and I believe that Darwin’s ideas have a value to contemporary science that has yet to be fully exploited.

Trying to communicate the richness of Darwin’s ideas puts me in the unenviable position of having to convince people that we don’t actually know the real Darwin and that he was an even greater, more creative, and more insightful thinker than he has been given credit for. I am convinced that most of those who think of themselves as Darwinians today—the neo-Darwinists—have gotten Darwin all wrong. The real Darwin has been excised from modern scientific hagiography.

The philosopher Daniel Dennett referred to evolution by natural selection—the subject of Darwin’s first great book, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection—as “Darwin’s dangerous idea.” Here I propose that Darwin’s really dangerous idea is the concept of aesthetic evolution by mate choice, which he explored in his second great book, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex.

Why is the idea of Darwinian mate choice so dangerous? First and foremost, Darwinian mate choice really is dangerous—to the neo-Darwinists—because it acknowledges that there are limits to the power of natural selection as an evolutionary force and as a scientific explanation of the biological world. Natural selection cannot be the only dynamic at work in evolution, Darwin maintained in Descent, because it cannot fully account for the extraordinary diversity of ornament we see in the biological world.

It took Darwin a long time to grapple with this dilemma. He famously wrote, “The sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick!” Because the extravagance of its design seemed of no survival value whatsoever, unlike other heritable features that are the result of natural selection, the peacock’s tail seemed to challenge everything that he had said in Origin. The insight he eventually arrived at, that there was another evolutionary force at work, was considered an unforgivable apostasy by Darwin’s orthodox adaptationist followers. As a consequence, the Darwinian theory of mate choice has largely been suppressed, misinterpreted, redefined, and forgotten ever since.

Aesthetic evolution by mate choice is an idea so dangerous that it had to be laundered out of Darwinism itself in order to preserve the omnipotence of the explanatory power of natural selection. Only when Darwin’s aesthetic view of evolution is restored to the biological and cultural mainstream will we have a science capable of explaining the diversity of beauty in nature.

Charles Darwin, a member of England’s nineteenth-century rural gentry, led a privileged life within the most elite class of an expanding global empire. Yet Darwin was no idle member of the upper class. A man of careful habits and a steady, hardworking disposition, he used his privilege (and his generous independent income) to support the searching of a stubbornly relentless intellect. By following where his interests took him, he ultimately discovered the fundamentals of modern evolutionary biology. He thus delivered a fatal blow to the hierarchical Victorian worldview, which put man on a pedestal above, and totally removed from, the rest of the animal kingdom. Charles Darwin became a radical despite himself. Even today the full creative impact of his intellectual radicalism—its implications for science and for the culture at large—has yet to be appreciated.

The traditional image of Darwin as a young man portrays him as an indifferent and undisciplined student who mostly liked to roam around outside collecting beetles. He dropped out of his original course of medical education and bounced aimlessly among various interests with little outward commitment to any of them until he was offered the opportunity to go on his famous Beagle voyage. According to legend, Darwin was transformed by his world travels and became the revolutionary scientist we remember today.

I think it more likely that Darwin had the same voracious, quiet, but stubborn intellect as a young man that he displayed later in life, an intellect that would have given him an instinctive sense of what good science looked like. Just prior to publishing On the Origin of Species in 1859, Darwin characterized the giant creationist masterwork of the world-famous Harvard professor Louis Agassiz, the Essay on Classification, as “utterly impracticable rubbish!” As a medical student, Darwin, I think, likely came to the same conclusion about most of his biological education. And he would have been right. Most of what was taught as medicine in the 1820s was impracticable rubbish. There was no central mechanistic understanding of the workings of the body and no broader scientific concept of the causes of disease. Medical treatments were a grab bag of irrelevant placebos, powerful poisons, and dangerous quackery. It would be hard to identify more than a handful of professional medical treatments from that time that would be recognized today as being likely to do any patient any good whatsoever. Indeed, in his autobiography Darwin describes his experience of attending lectures at the Royal Medical Society in Edinburgh: “Much rubbish was talked there.” I suspect that it was only when Darwin went all the way to the unexplored reaches of the Southern Hemisphere that he found an intellectual space free enough from the hidebound dogmas of his day to allow him the full play of his far-reaching, brilliant, and ever-curious mind.

Once he could make his own unfiltered observations, what he saw led him to the two great biological discoveries he revealed in Origin: the mechanism of evolution by natural selection, and the concept that all organisms are historically descended from a single common ancestor and thus related to one another in a “great Tree of Life.” The enduring debates in some corners over whether these ideas should be taught in public schools give us some sense of how profoundly they must have challenged Darwin’s readers a century and a half ago.

In confronting the fierce attacks that were mounted against Origin after its publication, Darwin had three gnawing problems. The first problem was the absence of any working theory of genetics. Not knowing the work of Mendel, Darwin struggled and failed to develop a functioning theory of inheritance, which was fundamental to the mechanism of natural selection. Darwin’s second problem was the evolutionary origin of human beings, human nature, and human diversity. When it came to human evolution, Darwin pulled his punches in Origin and evasively concluded only that “light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.”

Darwin’s third big problem was the origin of impracticable beauty. If natural selection was driven by the differential survival of heritable variations, what could explain the elaborate beauty of that peacock’s tail that troubled him so much? The tail obviously did not help the male peacock to survive; if anything, the huge tail would be a hindrance, slowing him down and making him much more vulnerable to predators. Darwin was particularly obsessed with the eyespots on the peacock’s tail. He had argued that the perfection of the human eye could be explained by the evolution of many incremental advances over time. Each evolutionary advance would have produced slight improvements in the ability of the eye to detect light, to distinguish shadows from light, to focus, to create images, to differentiate among colors, and so on, all of which would have contributed to the animal’s survival. But what purpose could the intermediate stages in the evolution of the peacock’s eyespots have served? Indeed, what purpose do the “perfect” eyespots of a peacock serve today? If the problem of explaining the evolution of the human eye was an intellectual challenge, the problem of explaining the peacock’s eyespot was an intellectual nightmare. Darwin lived this nightmare. It was in that context that in 1860 he wrote that oft-quoted line to his American friend the Harvard botanist Asa Gray: “The sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick!”

In 1871, with the publication of The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, Darwin boldly addressed both the problem of human origins and the evolution of beauty. In this book he proposed a second, independent mechanism of evolution—sexual selection—to account for armaments and ornaments, battle and beauty. If the results of natural selection were determined by the differential survival of heritable variations, then the results of sexual selection were determined by their differential sexual success—that is, by those heritable features that contribute to success at obtaining mates.

Within sexual selection, Darwin envisioned two distinct and potentially opposing evolutionary mechanisms at work. The first mechanism, which he called the law of battle, was the struggle between individuals of one sex—often male—for sexual control over the individuals of the other sex. Darwin hypothesized that the battle for sexual control would result in the evolution of large body size, weapons of aggression like horns, antlers, and spurs, and mechanisms of physical control. The second sexual selection mechanism, which he called the taste for the beautiful, concerned the process by which the members of one sex—often female—choose their mates on the basis of their own innate preferences. Darwin hypothesized that mate choice had resulted in the evolution of many of those traits in nature that are so pleasing and beautiful. These ornamental traits included everything from the songs, colorful plumages, and displays of birds to the brilliant blue face and hindquarters of the Mandrill (Mandrillus sphinx). In an exhaustive survey of animal life from spiders and insects to birds and mammals, Darwin reviewed the evidence for sexual selection in many different species. Using the law of battle and the taste for the beautiful, he proposed to explain the evolution of both armament and ornament in nature.

In The Descent of Man, Darwin finally presented the explicit theory of the evolutionary origins of humans that he had avoided articulating in Origin. The book begins with a long discussion of the continuity between human beings and other animals, slowly and incrementally chipping away at the edifice of human uniqueness and exceptionalism. Because of the obvious cultural sensitivity of the subject, Darwin proceeded at a very deliberate pace to build the argument for this evolutionary continuity. He put off until his final chapter, “General Summary and Conclusion,” the incendiary conclusion to which all this was leading: “We thus learn that man is descended from a hairy quadruped.”

Then, after discussing how sexual selection worked in the animal world, Darwin analyzed its impact on human evolution. From our furless bodies, to the enormous geographic, ethnic, and tribal diversity in human appearance, to our highly social character, to language and music, Darwin made a powerful case that sexual selection had played a critical role in the shaping of the human species:

Courage, pugnacity, perseverance, strength and size of body, weapons of all kinds, musical organs, both vocal and instrumental, bright colors, stripes and marks, and ornamental appendages, have all been indirectly gained…through the influence of love and jealousy, through the appreciation of the beautiful…and through the exertion of a choice.

Although tackling two subjects as complex and controversial as the evolution of beauty and the origins of humankind in one volume was an intellectually daring feat, Descent is generally considered a difficult, or even flawed, work. By building his argument so slowly and incrementally, writing in such dry, discursive prose, and citing so many learned authorities in support of the ideas he was advancing, Darwin might have thought he could draw any reasonable reader to accept the inevitability of his radical conclusions. But his rhetorical tactics failed, and in the end Descent was criticized by both creationist opponents of the very concept of evolution and fellow scientists who accepted natural selection but were adamantly opposed to sexual selection. To this day, Descent has never had the same intellectual impact as Origin.

The most notable and revolutionary feature of Darwin’s theory of mate choice is that it was explicitly aesthetic. He described the evolutionary origin of beauty in nature as a consequence of the fact that animals had evolved to be beautiful to themselves. What was so radical about this idea was that it positioned organisms—especially female organisms—as active agents in the evolution of their own species. Unlike natural selection, which emerges from external forces in nature, such as competition, predation, climate, and geography, acting on the organism, sexual selection is a potentially independent, self-directed process in which the organisms themselves (mostly female) were in charge. Darwin described females as having a “taste for the beautiful” and an “aesthetic faculty.” He described males as trying to “charm” their mates:

With the great majority of animals…the taste for the beautiful is confined to the attractions of the opposite sex.* The sweet strains poured forth by many male birds during the season of love are certainly admired by the females, of which fact evidence will hereafter be given. If female birds had been incapable of appreciating the beautiful colours, the ornaments, and voices of their male partners, all the labour and anxiety by the latter in displaying their charms before the females would have been thrown away; and this is impossible to admit…

On the whole, birds appear to be the most aesthetic of all animals, excepting of course man, and they have nearly the same taste for the beautiful as we have…[Birds] charm the female by vocal and instrumental music of the most varied kinds.

From the scientific and cultural perspectives of today, Darwin’s choice of aesthetic language may seem quaint, anthropomorphic, and possibly even embarrassingly silly. And that may help to account for why Darwin’s aesthetic view of mate choice is treated today like the crazy aunt in the evolutionary attic; she is not to be spoken of. Clearly, Darwin did not have our contemporary fear of anthropomorphism. Indeed, because he was vitally engaged in breaking down the previously unquestioned barrier between humans and other forms of life, his use of aesthetic language was not just a curious mannerism or a quaint Victorian affectation. It was an integral feature of his scientific argument about the nature of evolutionary process. Darwin was making explicit claims about the sensory and cognitive abilities of animals and the evolutionary consequences of those abilities. Having put humans and all other organisms on different branches of the same great Tree of Life, Darwin used ordinary language to make an extraordinary scientific claim: that the subjective sensory experiences of humans can be compared scientifically to those of the animals.

The first implication of Darwin’s language was that animals are choosing among their prospective mates on the basis of judgments about their aesthetic appeal. To many Victorian readers, even those sympathetic to evolution, this was patently absurd. It seemed impossible that animals could make fine aesthetic judgments. Even if they were able to observe differences in the color of their suitors’ plumage or the musical notes of their songs, the notion that they could cognitively distinguish among them, and then demonstrate a specific preference for one or another variation, was considered ludicrous.

These Victorian-era objections have been definitively rejected. Darwin’s hypothesis that animals are able to make sensory evaluations and exercise mate preferences is now supported by volumes of evidence and is universally accepted. There have been numerous experiments across the animal kingdom—from birds to fishes, grasshoppers to moths—showing that animals have the capacity to make sensory evaluations that influence their mate choices.

Although Darwin’s proposal of animal cognitive choice is now the accepted wisdom, the second implication of his aesthetic theory of sexual selection remains as revolutionary today, and as controversial, as when he first proposed it. By using the words “beauty,” “taste,” “charm,” “appreciate,” “admire,” and “love,” Darwin was suggesting that mating preferences could evolve for displays that had no utilitarian value at all to the chooser, only aesthetic value. In short, Darwin hypothesized that beauty evolves primarily because it is pleasurable to the observer.

Darwin’s views on this issue developed over time. In an early discussion of sexual selection in Origin, Darwin wrote, “Amongst many animals, sexual selection will give its aid to ordinary [natural] selection by assuring to the most vigorous and best adaptive of all males the greatest number of offspring.”

In other words, in Origin, Darwin saw sexual selection as simply the handmaiden of natural selection, another means of guaranteeing the perpetuation of the most vigorous and best-adapted mates. This view still prevails today. By the time he wrote Descent, however, Darwin had embraced a much broader concept of sexual selection that may have nothing to do with a potential mate’s being more vigorous or better adapted per se, but only with being aesthetically appealing, as he stated clearly for the mesmerizing example of the Argus Pheasant: “The case of the male Argus pheasant is eminently interesting, because it affords good evidence that the most refined beauty may serve as a sexual charm, and for no other purpose [emphasis added].”

Moreover, in Descent, Darwin viewed sexual selection and natural selection as two distinct and frequently independent evolutionary mechanisms. Thus, the concept of two distinct but potentially interacting and even conflicting sources of selection is a fundamental and vital component of an authentically Darwinian vision of evolutionary biology. As we will see, however, this view has been rejected by most modern evolutionary biologists in favor of Darwin’s earlier view of sexual selection as just another variant on natural selection.

Another distinctive feature of Darwin’s theory of mate choice was that it was coevolutionary. Darwin hypothesized that the specific display traits and the “standards of beauty” used to select a mate evolved together, mutually influencing and reinforcing each other—as demonstrated again by the Argus Pheasant:

The male Argus Pheasant acquired his beauty gradually through the preference of the females during many generations for the more highly ornamented males; the aesthetic capacity of females advanced through exercise or habit just as our own taste is gradually improved.

Here, Darwin envisions an evolutionary process in which each species coevolves its own, unique, cognitive “standards of beauty” in concert with the elaboration of the display traits that meet those standards. According to this hypothesis, behind every biological ornament is an equally elaborate, coevolved cognitive preference that has driven, shaped, and been shaped by that ornament’s evolution. By modern scientific criteria, Darwin’s description of the coevolutionary process in the Argus Pheasant is rather hazy, but it is no less substantive than his explanations of the mechanism of natural selection, which are viewed today as being brilliantly prescient, despite his ignorance of genetics.

Within Darwin’s argument for mate choice in Descent was another revolutionary idea: that animals are not merely subject to the extrinsic forces of ecological competition, predation, climate, geography, and so on that create natural selection. Rather, animals can play a distinct and vital role in their own evolution through their sexual and social choices. Whenever the opportunity evolves to enact sexual preferences through mate choice, a new and distinctively aesthetic evolutionary phenomenon occurs. Whether it occurs within a shrimp or a swan, a moth or a human, individual organisms wield the potential to evolve arbitrary and useless beauty completely independent of (and sometimes in opposition to) the forces of natural selection.

In some species—like penguins and puffins—there is mutual mate choice, and both sexes exhibit the same displays and coevolved mating preferences. In polyandrous species, like the phalaropes (Phalaropus) and lily-trodding jacanas (Jacanidae), successful females may take multiple mates. These females are larger and brighter than the males, and they’re the ones who perform courtship displays and sing songs to attract mates, while the males are the ones who exhibit mate choice, build the nests, and care for the young. But Darwin observed that in many of the most highly ornamented species the evolutionary force of sexual selection acted predominantly through female mate choice, which is why this book focuses largely on female mate choice. If female aesthetic preferences drove the process, then female sexual desire was responsible for creating, defining, and shaping the most extreme forms of sexual display that we see in nature. Ultimately, it is female sexual autonomy that is predominantly responsible for the evolution of natural beauty. This was a very unsettling concept in Darwin’s time—as it is to many today.

Because the concept sexual autonomy has not been well explored in evolutionary biology, it is worthwhile to define it and understand its far-reaching implications. Whether in ethics, political philosophy, sociology, or biology, autonomy is the capacity of an individual agent to make an informed, independent, and uncoerced decision. So, sexual autonomy is the capacity for an individual organism to exercise an informed, independent, and uncoerced sexual choice about whom to mate with. The individual elements of the Darwinian concept of sexual autonomy—that is, sensory perception, cognitive capacities for sensory evaluation and mate choice, the potential for independence from sexual coercion, and so on—are all common concepts in evolutionary biology today. Yet few evolutionary biologists since Darwin have aligned these dots as clearly as he did.

In Descent, Darwin presented his hypothesis that female sexual autonomy—the taste for the beautiful—is an independent and transformative evolutionary force in the history of life. He also hypothesized that it can sometimes be matched, counterbalanced, or even overwhelmed by an independent force of male sexual control: the law of battle, the combat among members of one sex for control over mating with the other sex. In some species, one evolutionary mechanism or the other may dominate the outcome of sexual selection, but in other species—ducks, for example, as we shall see—female choice and male competition and coercion will both be operative and can give rise to an escalating process of sexual conflict. Darwin did not have the intellectual framework to fully describe the dynamics of sexual conflict, but he clearly understood that it existed—in humans and in other animals.

In short, Descent was as mechanistically innovative and analytically thoughtful as Origin, but to most of Darwin’s contemporaries it was a bridge too far.

Upon publication in 1871, Darwin’s theory of sexual selection was swiftly and brutally attacked. Or more precisely, part of it was. Darwin’s concept of male-male competition—the law of battle—was immediately and almost universally accepted. Clearly, the notion of male-male competition for dominance over female sexuality was not a hard sell in the patriarchal Victorian culture of Darwin’s time. For example, in an initially anonymous review of Descent that appeared soon after the book was published, the biologist St. George Mivart wrote,

Under the head of sexual selection, Darwin put two very distinct processes. One of these consists in the action of superior strength or activity, by which one male succeeds in obtaining possession of mates and in keeping away rivals. This is, undoubtedly, a vera causa; but may be more conveniently reckoned as one kind of “natural selection” than as a branch of “sexual selection.”

In these few words, Mivart established an intellectual gambit that is still operative today. He took the element of Darwin’s sexual selection theory that he agreed with—male-male competition—and declared it to be just another form of natural selection, rather than an independent force, in direct opposition to Darwin’s own view. But at least he acknowledged that it existed. Not so the other aspect of Darwin’s sexual selection theory.

When he came to a consideration of female mate choice, Mivart launched an all-out attack: “The second process consists in the alleged preference or choice, exercised freely by the female in favour of particular males on account of some attractiveness or beauty of form, colour, odor, or voice which the males may possess.”

By referring to “choice, exercised freely,” Mivart documents that Darwin’s theory implied female sexual autonomy to his Victorian readers. However, the notion of an animal’s exercising any kind of choice was a complete impossibility to Mivart:

Even in Mr. Darwin’s specially-selected instances, there is not a tittle of evidence tending, however slightly, to show that any brute possesses the representative reflective faculties…It cannot be denied that, looking broadly over the whole animal kingdom, there is no evidence of advance in mental power on the part of brutes.

Mivart asserts that animals lack the requisite sensory powers, cognitive capacity, and free will necessary to make sexual choices based on display traits. Therefore, they could not possibly be active players, or selective agents, in their own evolution. Moreover, in discussing the role of the peahen in the evolution of the peacock’s tail, Mivart found the idea of choice being exercised by female “brutes” particularly preposterous: “such is the instability of vicious feminine caprice, [emphasis added] that no constancy of coloration could be produced by its selective actions.”

To Mivart, female sexual whims were so malleable—that is, fickle females preferring one thing one minute, and another the next—that they could never lead to the evolution of something as marvelously complex as the peacock’s tail.

We need to take a closer look at Mivart’s language, because the meanings of some of his words have changed in common English usage over the past 140 years. Today, the word “vicious” means intentionally violent or ferocious, but its original meaning was immoral, depraved, or wicked—literally, characterized by vice. Likewise, today “caprice” refers to a delightful, lighthearted whim, but in Victorian times it had the less appealing meaning of an arbitrary “turn of mind made without apparent or adequate motive.” Thus, to Mivart, the concept of female mate choice and autonomy had overtones not just of fickleness but of unjustifiable immorality and sin.

Mivart did concede that display might play a role in sexual arousal: “The display of the male may be useful in supplying the necessary degree of stimulation to her nervous system, and to that of the male. Pleasurable sensations, perhaps very keen in intensity, may thence result to both.”

Mivart’s evocation of “stimulation” that creates “pleasurable sensations” reads like advice for a fulfilling sex life from a Victorian marriage manual. In this view, females merely require sufficient stimulation in order to elicit an appropriate sexual response and coordinate their sexual behavior with that of the male.

But if the purpose of sexual display is simply to supply “the necessary degree of stimulation,” then females do not have their own individual, autonomous sexual desires. Rather, females should inevitably, and in due time, respond to the workmanlike stimulatory efforts of their suitors. This autonomy-denying conception of female sexual desire would reverberate throughout the next century, reaching its apogee in Freud’s theory of human sexual response (see chapter 9). According to this physiological interpretation of female sexual pleasure, men need never entertain the possibility that “maybe she’s just not that into you.” Absence of female sexual response always means that there is something wrong with her physiology—in short, that she’s frigid. As we will see, it is probably not an accident that the rediscovery of the biological theory of evolution by mate choice, the broad acknowledgment in Western culture of female autonomy, and the collapse of the Freudian conception of female sexuality all occurred during a short period of time that coincided with the advent of the women’s liberation movement in the 1970s.

Mivart’s review of Descent also established another enduring intellectual trend. He was the very first person to portray Darwin as a traitor to his own great legacy—a traitor to true Darwinism: “The assignment of the law of ‘natural selection’ to a subordinate position is virtually an abandonment of the Darwinian theory; for the one distinguishing feature of that theory was the all-sufficiency of ‘natural selection’ [emphasis added].”

Mere weeks after publication of Descent, Mivart mounted an attack against it that is still in use—citing Origin to argue against Descent. To Mivart, Darwin’s signature achievement had been the creation of a single, “all-sufficient” theory of biological evolution. By diluting the theory of natural selection with a mechanism that rested largely on the power of aesthetic subjective experiences—vicious feminine caprice—Darwin had gone beyond the pale of what was acceptable. Many evolutionary biologists would still agree.

Mivart’s attacks on sexual selection set many others in motion. But the most consistent, relentless, and effective critique of sexual selection came from Alfred Russel Wallace. Wallace was famous as the co-discoverer of the theory of natural selection. In 1859, he sent Darwin a manuscript from the jungles of Indonesia in which he set down a theory quite similar to Darwin’s, and he asked for his advice and assistance with the manuscript. Fearful of being preempted by the younger man after decades of private work on his theory of natural selection, Darwin quickly published Wallace’s article along with a short article summarizing his own theory. Then he rushed the full manuscript of On the Origin of Species into publication. By the time Wallace returned to England, Darwin and his theory were world famous.

There is no evidence that Wallace ever held this against Darwin, nor could he. Darwin had been working away on the idea of natural selection for more than twenty years, while Wallace was just beginning to think it through. But Darwin and Wallace never agreed on the subject of mate choice, and Wallace soon mounted a relentless attack on it. The two men debated their opposing views in a series of publications and in private letters that continued until Darwin’s death in 1882, with neither man ever changing his mind. In what turned out to be his last scientific publication, Darwin wrote, “I may perhaps be here permitted to say that, after having carefully weighed to the best of my ability the various arguments which have been advanced against the principle of sexual selection, I remain firmly convinced of its truth.”

In contrast to Darwin’s always polite and understated expression of his views, Wallace’s attack on evolution by mate choice grew ever more strident after Darwin’s death and continued until his own death in 1913. Ultimately, Wallace was so successful that the subject of sexual selection was almost completely marginalized and forgotten within evolutionary biology until the 1970s.

Wallace expended an enormous amount of energy arguing that the “ornamental” differences between the sexes that Darwin described were not ornaments at all and that Darwin’s theory of mate choice was unnecessary to explain animal diversity. Like Mivart, Wallace was skeptical about the possibility that animals had sensory and cognitive capacities to make mate choices. Wallace believed that humans had been specially created by God and divinely endowed with cognitive capacities that animals lacked. Thus, Darwin’s concept of mate choice violated Wallace’s spiritual theory of human exceptionalism.

However, faced with overwhelming evidence in the form of elaborate ornaments and displays, especially among birds, Wallace was never able to reject evolution by mate choice entirely. But when forced to admit the possibility, he insisted that sexual ornaments could only have evolved because they had an adaptive, utilitarian value. Thus, in his 1878 book, Tropical Nature, and Other Essays, under the heading “Natural Selection as Neutralizing Sexual Selection,” Wallace wrote, “The only way in which we can account for the observed facts is by supposing that colour and ornament are strictly correlated with health, vigor, and general fitness to survive.”

Here, Wallace articulates the idea that sexual displays constitute “honest” indicators of quality and condition—an entirely orthodox view in sexual selection today. But how can it be that Wallace, the man justly credited with having destroyed sexual selection theory for over a century, actually wrote a statement that would be entirely at home in any modern biology textbook, or practically any contemporary paper on mate choice? The answer is that today’s mainstream views of mate choice are as stridently anti-Darwinian as Wallace’s critiques.

Wallace was the first to propose the now exceedingly popular BioMatch.com hypothesis, which holds that all beauty provides a rich profile of practical information about the adaptive qualities of potential mates. This view of evolution has become so pervasive that it even found its way into the 2013 Princeton University graduation speech by the Federal Reserve chairman, Ben Bernanke, who admonished the graduates to “remember that physical beauty is evolution’s way of assuring us that the other person doesn’t have too many intestinal parasites.”

Today, most researchers agree with Wallace that all of sexual selection is simply a form of natural selection. But Wallace went further than they do and rejected the term “sexual selection” entirely. In that same passage, he continued,

If there is (as I maintain) such a correlation [between ornament and health, vigor, and fitness to survive], then the sexual selection of color or ornament, for which there is little or no evidence, becomes needless, because natural selection, which is the admitted vera causa, will itself produce all the results…Sexual selection becomes as unnecessary as it would certainly be ineffective.

Of course, it was the arbitrary and aesthetic components of Darwin’s theory of sexual selection that Wallace rejected as “needless,” “unnecessary,” and “ineffective.” Today, most evolutionary biologists would still agree.

Like Mivart, Wallace, who saw Darwin’s aesthetic heresy as a threat to their shared intellectual legacy, took steps to fix what he perceived as Darwin’s error. In the introduction to his 1889 book Darwinism, Wallace wrote,

In rejecting that phase of sexual selection depending on female choice, I insist on the greater efficacy of natural selection. This is pre-eminently the Darwinian doctrine, and I therefore claim for my book the position of being the advocate of pure Darwinism.

Here, Wallace claims to be more Darwinian than Darwin! After wrangling unsuccessfully over mate choice with the living Darwin, within just a few years of Darwin’s death Wallace has begun to reshape Darwinism in his own image.

In these passages, we witness the birth of adaptationism—the belief that adaptation by natural selection is a universally strong force that will always be predominant in the evolutionary process. Or, as Wallace put it in a strikingly absolutist statement, “Natural selection acts perpetually and on an enormous scale”—so enormous that it would “neutralise” any other evolutionary mechanisms.

Wallace set in motion the transformation of Darwin’s fertile, creative, and diverse intellectual legacy into the monolithic and intellectually impoverished theory with which he is almost universally associated today. Notably, Wallace also invented the characteristic style of adaptationist argument—mere stubborn insistence.

This is kind of a big deal. The Darwin we have inherited, through the filter of Wallace’s outsized influence on evolutionary biology in the twentieth century, has been laundered, retailored, and cleaned up for ideological purity. The true breadth and creativity of Darwin’s ideas, especially his aesthetic view of evolution, have been written out of history. Alfred Russel Wallace might have lost the battle for credit over the discovery of natural selection, but he won the war over what evolutionary biology and Darwinism would become in the twentieth century. More than one hundred years later, I am still pissed about it.

In the century following the publication of Darwin’s Descent of Man, the theory of sexual selection was almost entirely eclipsed. Despite a few scattered attempts to revive the topic, Wallace’s hatchet job on mate choice was so successful that generation after generation would turn exclusively to natural selection to account for sexual ornament and display behavior.

During the century-long dark age of mate choice theory, however, one man did make a fundamental contribution to the field. In a 1915 paper and a 1930 book, Ronald A. Fisher proposed a genetic mechanism for the evolution of mate choice that built on and extended Darwin’s aesthetic view. Unfortunately, however, Fisher’s ideas on sexual selection would be mostly ignored for the next fifty years.

Fisher was a gifted mathematician who had a huge effect on the sciences through his fundamental work developing both the basic tools and the intellectual structure underlying modern statistics. However, he was first and foremost a biologist, and his statistical research grew directly from his desire for a more rigorous understanding of the workings of genetics and evolution in nature, agriculture, and human populations. His interest in genetics and evolution was motivated in part by his ardent support for eugenics—the now disgraced theory and social movement that advocated the use of social, political, and legal regulation of reproduction in order to genetically improve the human species and maintain “racial purity.” Appalling as his beliefs were, Fisher’s investigations led him to some brilliant scientific conclusions—conclusions that, in the end, conflicted with his eugenic beliefs.

Fisher permanently reframed the sexual selection debate with a critical observation: Explaining the evolution of sexual ornaments is easy; all other things being equal, display traits should evolve to match the prevailing mating preferences. The more critical scientific question is, why and how do mating preferences evolve? This insight remains fundamental to all contemporary discussions of evolution by sexual selection.

Fisher actually proposed a two-stage evolutionary model: one phase for the initial origin of mating preferences, and a second, subsequent phase for the coevolutionary elaboration of trait and preference. The first phase, which is solidly Wallacean, holds that preferences initially evolve for traits that are honest and accurate indices of health, vigor, and survival ability. Natural selection would ensure that mate choice based on these traits would lead to objectively better mates and to genetically based mating preferences for these better mates. But then, after the origin of mating preference, Fisher hypothesized in his second-phase model, the very existence of mate choice would unhinge the display trait from its original honest, quality information by creating a new, unpredictable, aesthetically driven evolutionary force: sexual attraction to the trait itself. When the honest indicator trait becomes disconnected from its correlation with quality, that doesn’t make the trait any less attractive to a potential mate; it will continue to evolve and to be elaborated merely because it is preferred.

In the end, according to the Fisher phase-two model, the force that drives the subsequent evolution of mate choice is mate choice itself. In an exact reversal of the Wallacean view of natural selection as neutralizing sexual selection, arbitrary aesthetic choices (per Darwin) trump choices made for adaptive advantage (per Wallace), because the trait that was originally preferred for some adaptive reason has become a source of attraction in its own right. Once the trait is attractive, its attractiveness and popularity become ends in themselves. According to Fisher, mating preference is like a Trojan horse. Even if mate choice originally acts to enhance traits that carry adaptive information, desire for the preferred trait will eventually undermine the ability of natural selection to dictate the evolutionary outcome. Desire for beauty will endure and undermine the desire for truth.

How does this happen? Fisher hypothesized that a positive feedback loop between the sexual ornament and the mating preference for that ornament will evolve through genetic covariation (that is, correlated genetic variation) between the two. To understand how this could work, imagine a population of birds with genetic variation for a display trait—say tail length—and for mating preferences for different tail lengths. Females who prefer males with long tails will find mates with those longer tails. Likewise, females who prefer males with shorter tails will find mates with shorter tails. The action of mate choice means that variation in genes for traits and preferences will no longer be found randomly in the population. Rather, most individuals will soon carry genes for correlated traits and preferences—that is, genes for long tails and preferences for long tails, or genes for short tails and preferences for short tails. Likewise, there will be fewer and fewer individuals who carry genes for short tails and preferences for long tails, or vice versa. The very action of mate choice will distill and concentrate genetic variation for trait and preference into correlated combinations. To Fisher, this observation was merely a mathematical fact. This outcome is what mating preference means.

As a consequence of genetic covariation, genes for a given trait and the preference for that trait will coevolve with each other. When females exercise their mate choices based on particular displays—for example, a long tail—they will also be selecting indirectly on particular mate choice genes, because they will be choosing mates whose mothers likely also had genes for preferring long tails.

The result is a strong, positive feedback loop in which mate choice becomes the selective agent in the evolution of mate preference itself. Fisher called this self-reinforcing sexual selection mechanism “a runaway process.” Selection on specific display traits creates evolutionary change in mating preferences, and evolutionary change in mating preferences will create further evolutionary change in display traits, and so on. The form of beauty, and the desire for it, shape each other through a coevolutionary process. In this way, Fisher provided an explicit genetic mechanism for how the display trait and the mating preference can “advance together,” as Darwin first envisioned for the Argus Pheasant (see quotation on this page).

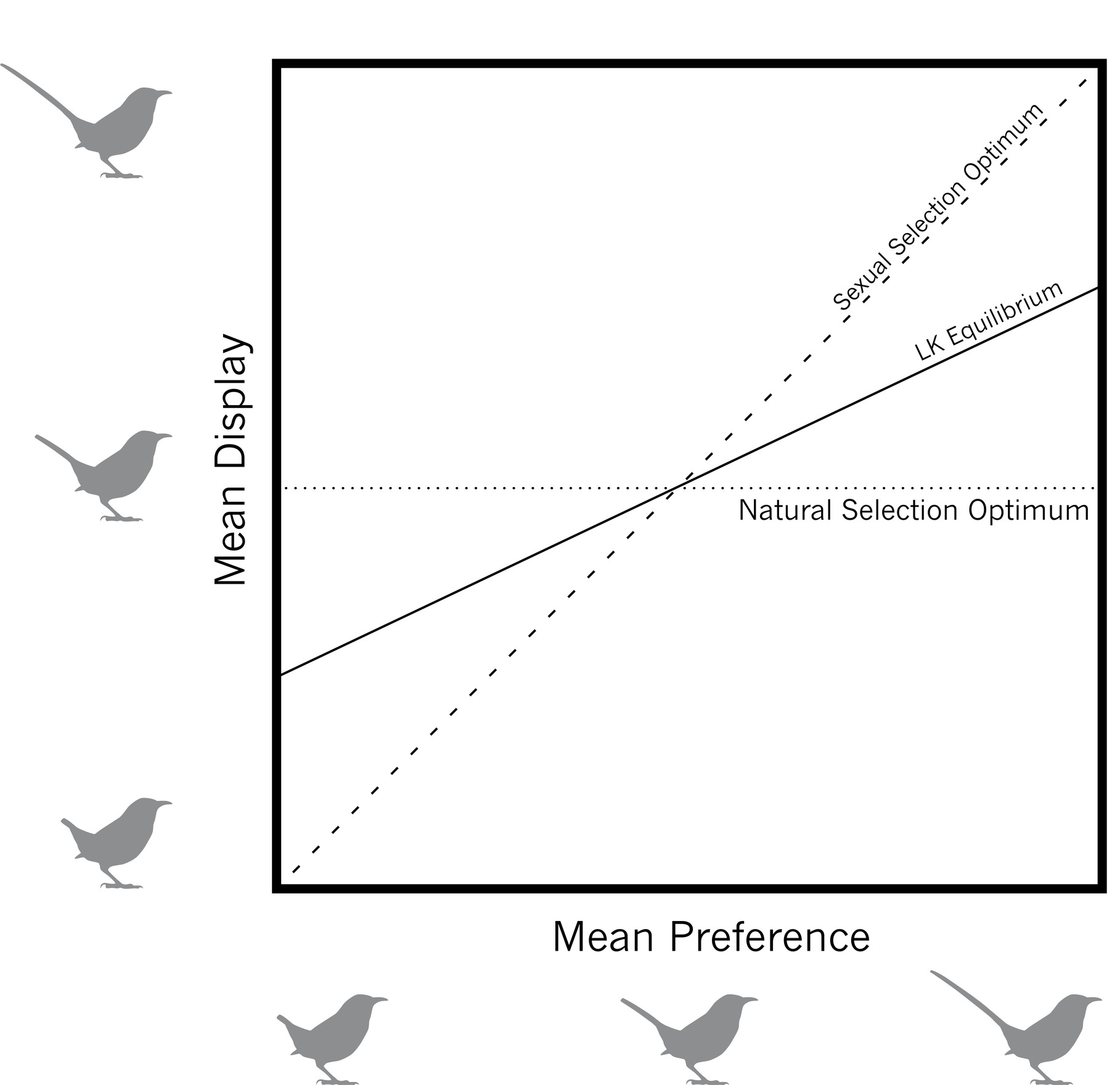

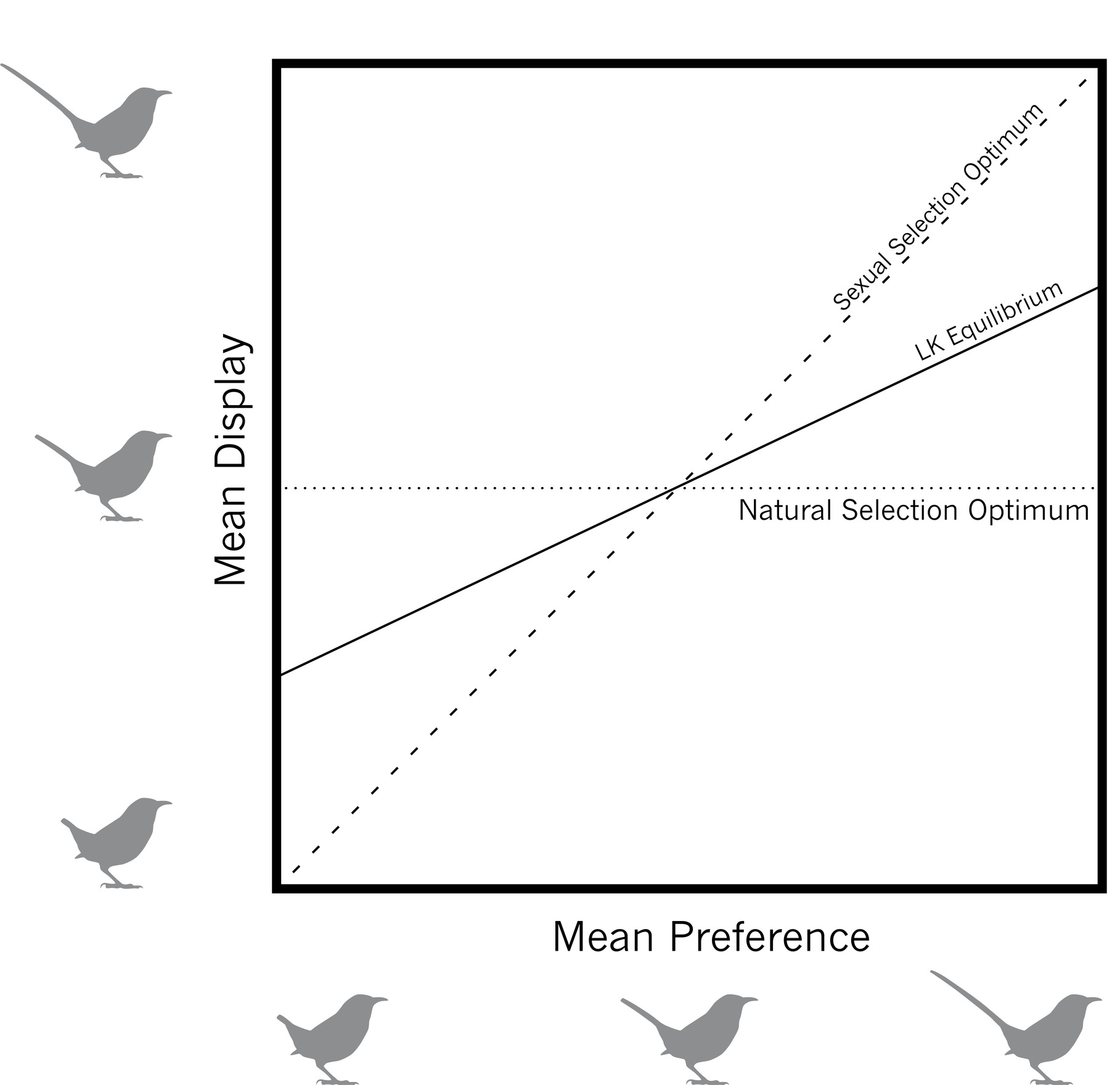

Evolution of genetic covariance between a display trait—for example, tail length—and a mating preference for it. (Top) A population begins with individuals (black dots) that have a random distribution of genetic variation for the display trait (vertical axis) and mating preference (horizontal axis). As a result of preference, many matings will occur among individuals in the upper right and lower left quandrants who have and prefer the same variations in tail length (+ signs). Few matings will occur in the other parts of the distribution where preferences and traits do not match (- signs). (Bottom) The result is the evolution of covariation between genes for the display and the preference (dotted line).

Fisher’s coevolutionary mechanism also explains the potential evolutionary benefit of mating preference. If the female chooses a mate with a sexually attractive trait—again let’s say a long tail—her male offspring will be more likely to inherit this sexually attractive trait. If other females in the population also prefer long tails, then the female will end up with a greater number of descendants, because her male offspring will be sexually attractive to them. This evolutionary advantage is the indirect, genetic benefit of mate choice alone. We call it indirect because it does not accrue directly to the chooser’s own survival or fecundity (that is, her capacity to have and raise offspring), or even to the survival of her offspring. Rather, the benefit accrues through the reproductive success of her sexually attractive sons, which will result in a wider propagation of her genes (that is, more grandkids).

Fisher’s runaway process works something like the Dutch tulip bulb craze of the 1630s, the speculative financial market bubble of the 1920s, or, to take something much more recent, the overvalued housing markets that led to the near collapse of the entire world banking system in 2008. All of these are examples of what happens when the value of something becomes unhinged from its “actual” worth and continues not only to be valued but to increase in value. What drives speculative market bubbles is desire itself. That is, something is desirable because it is desired, popular because it’s popular. Thus, Fisherian mate choice is the genetic version of the “irrational exuberance” of a market bubble. (We will return to this economic analogy in chapter 2.)

Fisher asserted that mating preferences do not continue to evolve because the particular male that the female chooses is any better than any other male. In fact, sexually successful males could sometimes evolve to be worse at survival or poorer in health or condition. If a display trait becomes disconnected from any other, extrinsic measure of mate quality—that is, overall genetic quality, disease resistance, diet quality, or ability to make parental investments—then we say that that display trait is arbitrary. Arbitrary does not mean accidental, random, or unexplainable; it means only that the display trait communicates no other information than its presence. It simply exists to be observed and evaluated. Arbitrary traits are neither honest nor dishonest, because they do not encode any information that can be lied about. They are merely attractive, or merely beautiful.

This evolutionary mechanism is rather like high fashion. The difference between successful and unsuccessful clothes is determined not by variation in function or objective quality (really) but by evanescent ideas about what is subjectively appealing—the style of the season. Fisher’s model of mate choice results in the evolution of traits that lack any functional advantages and may even be disadvantageous to the displayer—like stylish shoes that hurt one’s feet, or garments so skimpy that they fail to protect the body from the elements. In a Fisherian world, animals are slaves to evolutionary fashion, evolving extravagant and arbitrary displays and tastes that are all “meaningless”; they do not involve anything other than perceivable qualities.

Fisher never presented an explicit mathematical model of his runaway process (something that later biologists did, as we shall soon see). Some have conjectured that he was such a skilled mathematician that he thought the results were obvious and needed no further explication. If so, then Fisher was sorely mistaken, because there were plenty of discoveries still to be made. Actually, I think Fisher probably knew there was more work to do. So why didn’t he do it? I think Fisher did not pursue his runaway model any further because he realized that the implications of this evolutionary mechanism were completely antithetical to his personal support for the eugenics movement. Fisher’s runaway model implied that adaptive mate choice—the kind of choice required to eugenically “improve” the species—was evolutionarily unstable and would almost inevitably be undermined by arbitrary mate choice, the irrational desire that beauty inspires. And he was right!

Around the centennial of Darwin’s Descent of Man, the concept of sexual selection began to return to the evolutionary mainstream. Why did it take so long? Although it would require an extensive historical and sociological study to investigate my hunch, I don’t think it was a coincidence that evolutionary biologists finally began to reconsider mate choice, particularly female mate choice, as a genuine evolutionary phenomenon at precisely that moment when women in the United States and Europe began to organize politically and to protest for equal rights, sexual freedom, and access to birth control. It would be nice to think that the insights from evolutionary biologists had an influence on these positive cultural developments, but unfortunately history shows that the opposite was true.

With the return of the scientific interest in mate choice, there came a renewed battle between the aesthetic Darwinian/Fisherian view and a rejuvenated version of neo-Wallacean adaptationism. In 1981 and 1982, more than fifty years after Fisher published his model of sexual selection, the mathematical biologists Russell Lande and Mark Kirkpatrick independently confirmed and expanded upon it. Inspired by Fisher’s theory, Lande and Kirkpatrick applied different mathematical tools to explore the coevolutionary dynamics between mate choice and display traits and got very similar answers. They showed that traits and preferences can coevolve merely because of the advantage of sexually attractive offspring alone. Further, they demonstrated that the process of mate choice can create a covariance between the genes for a given display and the genes for the preference for that display.

The Lande-Kirkpatrick sexual selection models also confirmed mathematically that display traits evolve through a balance between natural selection and sexual selection. For example, a male may have the optimal tail length for survival (that is, favored by natural selection), but if he is not sexy enough to attract even a single mate (that is, disfavored by sexual selection), he will fail to pass on his genes to the next generation. Likewise, a male may have the perfect tail size for attracting mates (that is, favored by sexual selection), but if he is so sexually extravagant that he cannot survive long enough to attract a single mate (that is, disfavored by natural selection), he will also fail to pass on his genes. Lande and Kirkpatrick confirmed the intuition of Darwin and Fisher that natural and sexual selection on display traits will establish a balance between the two opposing forces. At this equilibrium, the male may still be quite far from the natural selection optimum, but that’s the cost of doing business with sexually autonomous, choosy females.

Lande-Kirkpatrick model for the evolution of a display trait—such as tail length—and a mating preference for it. The mean display trait in a population (vertical axis) will evolve toward an equilibrium (solid line) between the trait value favored by natural selection (horizontal line) and the trait value favored by sexual selection (broken line).

However, Lande and Kirkpatrick went well beyond Fisher and Darwin in defining this equilibrium. Using different mathematical frameworks, they each discovered that this balance between natural and sexual selection is not restricted to a single point. Rather, there exists a line of equilibria—literally, an infinite number of possible stable points of balance between natural and sexual selection on a given display trait. Essentially, for any perceivable display trait, there is some conceivable combination of sexual selection and natural selection acting on that trait that could result in a stable equilibrium. That is the true meaning of an “arbitrary” trait; practically any perceivable feature could function as a sexual ornament. Of course, the further away a display trait is from the natural selection optimum, the stronger the sexual advantage must be for it to evolve.

How do sexual and natural selection on display traits reach a balance? In other words, how will populations evolve toward equilibrium? Here, too, Lande and Kirkpatrick provided a rich mathematical machinery to flesh out Fisher’s verbal, nonmathematical model. In order to evolve to a stable equilibrium, both the mating display trait and the mating preference must coevolve. In other words, in order for females to get what they want (that is, evolve to an equilibrium), they must select on and change the male display trait. But because traits and preferences are genetically correlated, coevolution means that the females must also change what they want. By (a rather strained) analogy, this evolutionary process is a little bit like a marriage: spouses frequently attempt to change each other, and they frequently succeed. But the process of reaching a stable resolution usually requires a transformation both of one spouse’s behavior and of the other spouse’s opinion of that behavior.

In theory, aesthetic coevolution may sometimes occur so rapidly that display traits cannot evolve fast enough to satisfy the increasingly radical preferences of a population. Lande showed that if the genetic correlation between preference and traits is strong enough, it is theoretically possible for populations to evolve away from the line of equilibrium; that is, the line of equilibrium may become unstable. This process is considered the ultimate realization of Fisher’s “runaway” process, in which mate choice ends up changing itself so rapidly that its ever-evolving preferences can never be met and desire can never be fully satisfied.

Last, Lande’s and Kirkpatrick’s mathematical models also explain how mate choice could drive the evolution of new species. When populations of a given species become isolated from one another (for example, as a new mountain range rises, or deserts form, or rivers are rerouted), these populations will be subject to different random influences. Each subpopulation will ultimately diverge in its own unique aesthetic direction to a distinct point on the equilibrium line, toward its own differentiated standard of beauty: longer tails or shorter tails; higher-pitched songs or lower-pitched songs; red bellies or yellow bellies; blue heads, bare heads, or even bare, blue heads. The possibilities are endless. If the isolated populations diverge far enough from each other, the process of aesthetic sexual selection may result in an entirely new species—a process called speciation. According to this theory, aesthetic evolution is like a spinning top. The action of mate choice creates an internal equilibrium that determines what is sexually beautiful within a population. But random perturbations of the top—either internal forces like mutation or external factors like population isolation by a geographic barrier—can cause the top to spin away toward a new equilibrium.

The overall result is that mate choice fosters the evolution of ever-escalating and ever-diversifying standards of beauty among populations and species. Practically anything is possible—an idea for which there is ample evidence in some of the birds that populate these pages. I call them aesthetic extremists for good reason.

Russ Lande and Mark Kirkpatrick were directly inspired by the nearly forgotten aesthetic mate choice mechanisms of Darwin and Fisher. However, the modern, adaptationist, neo-Wallacean mechanism of mate choice had to be reinvented from scratch because no one remembered Wallace’s own honest advertisement theory. Yet the modern versions are strikingly similar to Wallace’s in logic; that is, they share his fundamental insistence on the greater efficacy of natural selection. Natural selection must be true, and all sufficient, because it is such a powerful and rationally attractive idea.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the chief proponent of the neo-Wallacean view of adaptive mate choice was Amotz Zahavi, a charismatic and energetic Israeli ornithologist with a fierce independent streak. In 1975, Zahavi published his “handicap principle.” A scientific megahit, this paper was a huge stimulus to the study of mate choice and has now been cited over twenty-five hundred times. Zahavi thought his ideas were entirely new. According to him, “Wallace…dismissed altogether the theory of sexual selection by mate preference.” However, the beautifully intuitive core idea of Zahavi’s handicap principle is precisely neo-Wallacean: “I suggest that sexual selection is effective because it improves the ability of the selecting sex to detect quality in the selected sex.”

Although Zahavi precisely restated Wallace’s adaptive mate choice hypothesis, he abandoned Wallace’s rhetoric by using the newly rehabilitated term “sexual selection,” instead of “natural selection,” to describe it. But Zahavi also added his own distinctive twist to Wallace’s logic. To Zahavi, the entire point of any sexual display is that it is a costly burden to the signaler—literally, a handicap. By its very existence, the ornamental handicap demonstrates the superior quality of the signaler because the signaler has been able to survive it. He wrote, “Sexual selection is effective only by selecting for a character that lowers the survival of the organism…It is possible to consider a handicap as a kind of test.”

The more elaborate the display trait, the greater the costs, the bigger the handicap, the more rigorous the test, and the better the mate. The individual who is attracted to a mate with such a costly trait is responding not to its subjective beauty, which is incidental to its costs, but to what it tells her about the male’s ability to rise above its cost. This is the handicap principle.

In what way was the handicapped male better? To Zahavi, it was clear that he could be better in any imaginable way. However, those who followed Zahavi established that the adaptive benefits of honest signaling could be of two basic kinds—direct and indirect. The direct benefits of mate choice include any advantages to the health, survival, or fecundity of the choosers themselves. Such adaptive direct benefits could include choosing a mate who provides extra protection from predators, a better territory with more food or better nesting sites, no sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), a greater capacity to invest in the feeding and protection of offspring, or lower mate search costs. Alternatively, the adaptive indirect benefits are in the form of good genes that are inherited by the chooser’s offspring and contribute to their survival and fecundity. Like the indirect Fisherian benefit of having sexy offspring, the good genes benefit doesn’t help the chooser directly but results in a greater number of grandchildren. However, unlike the indirect Fisherian benefit, the chooser’s offspring are not merely more attractive but actually better at surviving and reproducing, not merely at acquiring and fertilizing mates. Thus, good genes are different from the genes for the display trait itself, and theoretically they should provide heritable advantages to both male and female offspring.

Both direct benefits and good genes are adaptive benefits to mate choice; they can only occur when, as first proposed by Wallace, observable variation in the display trait among potential mates is correlated with some additional advantage that will contribute to the survival or fecundity of the choosers or their offspring. These correlations arise from an interaction between sexual selection on mating/fertilization success and natural selection on survival and fecundity. Zahavi’s handicap principle was a new proposal about how the adaptive correlation between display and mate quality arises and how it can be maintained.

Zahavi promoted the handicap principle with a single-minded fervor. But his idea had one big flaw. If the sexual advantage of an ornament is directly proportional to its survival costs, then the two forces will cancel each other out, and neither the costly ornament nor a mating preference for it can evolve. In a 1986 paper boldly titled “The Handicap Mechanism of Sexual Selection Does Not Work,” Mark Kirkpatrick provided a mathematical proof of this evolutionary trap.

To understand this problem, let’s consider a corollary of Zahavi’s handicap principle. I call it the “Smucker’s principle.” Smucker’s jelly takes its name from its founder, Jerome Monroe Smucker, who opened a cider press in Orrville, Ohio, in 1897. Readers of a certain age may recall the company’s catchy advertising slogan: “With a name like Smucker’s, it has to be good!” The slogan claims that the Smucker’s brand name is so unappealing, so off-putting, so costly, that the fact that the company has survived with this name proves that its jelly is of really high quality. The Smucker’s slogan embodies the handicap principle.

But let’s look a little more carefully at the implications of the Smucker’s principle. What if Smucker’s jelly were suddenly in competition with another jelly with an even worse, more costly name? Wouldn’t an even worse, more off-putting name indicate a jelly of even higher quality? What limits the possibility of ever-worsening and more costly names indicative of ever-higher-quality jellies?

Luckily, this exact thought experiment has already been conducted in a parody of the Smucker’s ad performed as a fake advertisement sketch on Saturday Night Live in the 1970s:

JANE CURTIN: And so, with a name like Flucker’s, it’s got to be good.

CHEVY CHASE: Hey, hold on a second, I have a jam here called Nose Hair. Now, with a name like Nose Hair, you can imagine how good it must be. MMM MMM!!

DAN AYKROYD: Hold it a minute, folks, but are you familiar with a jam called Death Camp? That’s Death Camp! Just look for the barbed wire on the label. With a name like Death Camp, it must be so good it’s incredible! Just amazingly good jam!

From there the names got worse and worse. John Belushi promoted a jelly called Dog Vomit, Monkey Pus, and then Chevy Chase returned with yet another new jelly named Painful Rectal Itch. The competition culminated with a jelly whose name was so repulsive it induced nausea and could not be spoken on the air. “So good, it’s sick making!” Jane Curtin proclaimed, before signing off with “Ask for it by name!”

The “Smucker’s principle” reveals the internal logical flaw of Zahavi’s “handicap principle.” As Kirkpatrick proved mathematically, if the sexual benefit of a signal is directly related to its costs, the signaler will never gain any advantage. Rather, handicaps will fail under their own costly burden. Fortunately, that means we can all rest easy that there will never be a jelly named Painful Rectal Itch.

The Smucker’s principle further demonstrates that Zahavi’s handicap principle is fundamentally incompatible with the aesthetic nature of sexual display. Sexual displays actually evolve because they are attractive, not disgustingly informative or repulsively honest. If the sole purpose of sexual display is to communicate the capacity to survive a great burden, then why are sexual traits ornamental? Why isn’t acne sexually attractive? After all, acne is frequently an honest indicator of a surge of adolescent hormones and would therefore provide reliable information about youth and fertility. Why don’t organisms evolve genuine handicaps like partially formed body parts? Why don’t individual organisms gnaw off a limb to show how good they are at surviving without the missing appendage? Why not two limbs? That would really say something about how hardy they are! Or, why not poke out an eye? The reason, or course, is that the handicap principle is disconnected from the fundamentally aesthetic nature of mate choice and therefore nearly irrelevant to nature.

In 1990, Alan Grafen at Oxford came to the rescue of the failing handicap principle. The stakes were high. The entire neo-Wallacean mate choice paradigm was on the line. Of course, Grafen was forced to acknowledge Kirkpatrick’s proof of the failure of the handicap principle as originally articulated by Zahavi. However, Grafen showed mathematically that a nonlinear relationship between display cost and mate quality could salvage the theory. In other words, if lower-quality males pay a proportionally higher cost to grow or display an attractive trait than do higher-quality males, then the handicap could evolve. If a handicap is like a test, then Grafen proposed that higher-quality individuals basically get an easier test. The only way to fix the handicap principle was to actually break it.

Having established a way to salvage handicaps, Grafen then asked how we should decide between two plausible evolutionary alternatives, the Zahavian handicap and the Fisherian runaway as elaborated by Lande and Kirkpatrick:

According to the handicap principle,…there is a rhyme and reason in the incidence and form of sexual selection…This is in contrast to the Fisher process, in which the form of the signal is more or less arbitrary and whether a species has undergone a bout of runaway selection is more or less a matter of chance.

In the Wallacean tradition, Grafen strongly endorsed the comforting “rhyme and reason” of adaptation over the unnerving arbitrariness of aesthetic Darwinism. Then Grafen went in for the kill: “To believe in the Fisher-Lande process as an explanation of sexual selection without abundant proof is methodologically wicked.”

I do not know of any other contemporary scientific debate in which one side has actually been branded as wicked! Not even cold fusion! Clearly, this is not an everyday scientific debate. In a striking reprise of St. George Mivart’s moralizing tone, Grafen’s outsized response indicates the intellectual magnitude of what is at stake. Darwin’s really dangerous idea—aesthetic evolution—is so threatening to adaptationism that it must be branded as wicked. Nearly one hundred years after Wallace advocated his pure form of Darwinism, Grafen deploys the same Wallacean insistence to try to win the debate again.

Grafen’s reasoning struck a chord. Although personal comfort is not a scientifically justifiable criterion, many people, including scientists, do want to believe that the world is filled with “rhyme and reason.” So, even though Grafen merely demonstrated that there were conditions under which the handicap principle could work, he so discredited the Fisherian theory that most evolutionary biologists concluded that the handicap principle not only could work but would work—all the time. If belief in the alternative hypothesis is “wicked,” there’s little choice to make. Adaptive mate choice has dominated the scientific discourse ever since.

In comparing the intellectual styles of Zahavi and Fisher, Grafen wrote that “Fisher’s idea is too clever by half” but that “Zahavi’s upward struggle from fact will triumph.” This distinction between cleverness and fact also lent itself to a narrative in which the proponents of arbitrary Fisherian mate choice were cast as pointy-headed mathematicians with no appreciation of the natural world, while adaptationist advocates of the handicap principle were seen as salt-of-the-earth natural historians. Matt Ridley brought this distinction to vivid life in his 1993 book, The Red Queen:

The split between Fisher and Good-genes began to emerge in the 1970s once the fact of female choice had been established to the satisfaction of most. Those of a theoretical or mathematical bent—the pale, eccentric types umbilically attached to their computers—became Fisherians. Field biologists and naturalists—bearded, besweatered, and booted—gradually found themselves to be Good-geners.

Ironically, I find that I have been written out of the historical narrative of my own discipline. I have spent cumulative years of my life in tropical forests on multiple continents studying avian courtship displays. I have been as “bearded, besweatered, and booted” as any field biologist. Yet I have also been an ardent and inquisitive “Fisherian” since the mid-1980s. According to the Grafen and Ridley narrative, I do not exist. Neither does Darwin, a naturalist who certainly put in his time in the field. Odder still, neither does Grafen, who is primarily a mathematician. Unfortunately, Ridley’s scenario also eliminates from consideration all female field biologists and naturalists. (Sorry, Jane Goodall and Rosemary Grant!) Of course, the function of this kind of intellectual fable is to obscure the actual complexity of the issues, to use rhetoric to claim the higher ground by portraying adaptationists as romantic figures with deeper personal connections to nature and to knowledge.

The author—“bearded, besweatered, and booted”—in the field recording bird songs on a reel-to-reel tape recorder with a parabolic microphone at 2900 meters altitude near Laguna Puruhanta in the Ecuadorian Andes in 1987.

The intellectual origins of aesthetic evolution are not in abstract mathematics but in Darwin’s own, bold realization of the evolutionary consequences of the subjective aesthetic experiences of animals and the intellectual insufficiency of natural selection to explain the phenomenon of beauty in nature. Nearly 150 years later, the best path to appreciating how beauty has come into being is still to follow in Darwin’s footsteps.

The Darwin versus Wallace, aesthetic versus adaptationist debate remains vital to science today. Whenever we study mate choice, we are using intellectual tools that were shaped by this debate, and we need to be aware of the history of our tools.

Among those tools is the language we use to define concepts in evolutionary biology. For example, let’s examine the history of the word “fitness.” To Darwin, fitness had the ordinary language meaning of physical fitness. Fitness meant fit to do a task. Darwinian fitness was the physical capacity to do the tasks necessary to ensure one’s survival and capacity for reproduction. However, during the development of population genetics in the early twentieth century, fitness was redefined mathematically as the differential success of one’s genes in subsequent generations. This broader and more general new definition combined all sources of differential genetic success—survival, fecundity, and mating/fertilization success—into a single variable under the common label of “adaptive natural selection.” The redefinition of fitness was accomplished precisely during the period when sexual selection by mate choice had been entirely rejected as irrelevant to evolutionary biology. Thus, the effect of redefining fitness was to flatten and eliminate the original, subtle, Darwinian distinction between natural selection on traits that ensured survival and fecundity and sexual selection on traits that resulted in differential mating and fertilization success. Ever since, this mathematically convenient but intellectually muddled new concept of fitness has reshaped how people think evolution works and made it difficult to even articulate the possibility of a distinct, independent, nonadaptive sexual selection mechanism. If it contributes to fitness, it must be adaptive, right? The Darwinian/Fisherian concept of sexual selection by mate choice has been essentially written out of the language of biology. It has become linguistically impossible to be an authentic Darwinian.

The flattening of the intellectual complexity of aesthetic Darwinism was motivated, at least in part, by the belief that conceptual unification is a general scientific virtue, that the development of fewer more powerful, more broadly applicable, singular theories, laws, and frameworks is a fundamental goal of science itself. Sometimes unification in science works great, but it is doomed to fail when the distinctive, emergent properties of particular phenomena are reduced, eliminated, or ignored in the process. This loss of intellectual content is exactly what happens when something complex is explained away instead of being explained in its own right.

By claiming that evolution by mate choice was a special process with its own, distinctive internal logic, Darwin fought against the powerful scientific and intellectual bias toward simplicity and unification. Of course, many of Darwin’s Victorian antagonists were recent converts from religious monotheism to materialist evolutionism. Their historic monotheism might have predisposed them to adopt a powerful new monoideism; they replaced a single omnipotent God with a single omnipotent idea—natural selection. Indeed, contemporary adaptationists should question why they feel it is necessary to explain all of nature with a single powerful theory or process. Is the desire for scientific unification simply the ghost of monotheism lurking within contemporary scientific explanation? This is another implication of Darwin’s really dangerous idea.

If evolutionary biology is to adopt an authentically Darwinian view, it must recognize, as he did, that natural selection and sexual selection are independent evolutionary mechanisms. In this framework, adaptive mate choice is a process that occurs through the interaction of sexual selection and natural selection. I will use this language throughout this book.

To better understand the evolution of beauty and how to study it, we will now take a look at the sex lives of birds. There can be no better place to start than with Darwin’s “eminently interesting” Great Argus pheasant.