CHAPTER 3

Manakin Dances

How, and why, has beauty changed within and among bird species over the course of millions of years? What determines what any given species finds beautiful? What, in short, is the evolutionary history of avian beauty?

These questions might seem impossible to answer, but we actually have many of the scientific tools we need to address them productively. One of the challenges to understanding the evolution of beauty is the complexity of animal displays and mating preferences. Fortunately, we do not need to invent a trendy new brand of “systems science” in order to investigate these complex aesthetic repertoires, because the science of natural history—the observation and description of the lives of organisms in their natural environments—provides us with exactly the tools we need. Natural history was a critical component of Darwin’s scientific method and remains a bedrock foundation of much of evolutionary biology today.

Once we have gathered information about individual species, we need other scientific methods to compare and analyze them and to uncover their complicated, often hierarchical evolutionary histories. The scientific discipline that enables us to do that is called phylogenetics. Phylogeny is the history of evolutionary relationships among organisms—what Darwin called the “great Tree of Life.”

Darwin proposed that discovery of the Tree of Life should become a major branch of evolutionary biology. Unfortunately, research interest in phylogeny was largely abandoned by evolutionary biology during most of the twentieth century. However, powerful new methods for reconstructing and analyzing phylogenies have been developed in recent decades, which has led to a revival of interest. So, now that the two critical intellectual tools necessary to study the evolution of beauty—natural history and phylogenetics—are available, there has never been a better time to be asking questions about how beauty, and the taste for it, evolve.

Doing so will help us to understand the process of evolutionary radiation—diversification among species—in a new way. In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is the process by which a single common ancestor evolves through natural selection into a diversity of species that have a great variety of ecologies or anatomical structures. The amazing diversity of Darwin’s Finches (Geospizinae) on the Galápagos Islands is a canonical example of adaptive radiation. In this chapter, however, we will investigate another group of birds—the neotropical manakins—in order to understand a different kind of evolutionary process: aesthetic radiation. Aesthetic radiation is the process of diversification and elaboration from a single common ancestor through some mechanism of aesthetic selection—especially mate choice. Aesthetic radiation does not preclude the occurrence of adaptive mate choice, but also includes arbitrary mate choice for sexual beauty alone, with all of its often dramatic coevolutionary consequences.

The science of beauty requires that we get out of the laboratory and the museum and into the field. Fortunately, my bird-watching youth was great basic training for doing natural history research on birds in the field. I discovered the second critical element of this branch of beauty studies—phylogenetics—as an undergraduate at Harvard University. My immersion in formal ornithological studies began in the fall of 1979 with a freshman seminar, the Biogeography of South American Birds taught by Dr. Raymond A. Paynter Jr., the curator of birds at the Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ). Dr. Paynter introduced me to the intellectual magic of natural history museums. Up on the fifth floor of the huge and ancient brick building that housed the Bird Department was a series of rooms where hundreds of thousands of scientific bird specimens were curated. During my undergraduate years, the MCZ was my intellectual home. I hung out a lot in the bird collections doing bibliographic work and curatorial tasks for Paynter and generally smelling like mothballs.

Dr. Paynter himself was far too intellectually conservative and cautious to be interested in the revolutionary new field of phylogenetics. But I soon discovered that the latest concepts and methods in this field were being hotly debated downstairs in the Romer Library in the weekly meetings of the Biogeography and Systematics Discussion Group. In retrospect, this time at Harvard was a golden era for phylogenetics. From the meetings of this “revolutionary cell” in the Romer Library, multiple graduate students went out into the world and made fundamental contributions to the field, helping to bring phylogeny back into the mainstream of evolutionary biology.

My own work was profoundly shaped by those weekly discussions in the early 1980s. I became fascinated by phylogenetic methods and eager to reconstruct avian family trees. For my senior honors project, I worked on the phylogeny and biogeography of toucans and barbets. Working at a desk I made for myself on a big table beneath the towering skeleton of an extinct moa in room 507 of the bird collection, I was excited to make observations of toucan plumage and skeletal characters and to construct my first phylogenies. I am happy to say that I have been continuously associated with world-class scientific collections of birds ever since. Only, I don’t smell like mothballs anymore.

As graduation approached, I was casting about for what to do next, searching for a research program that would combine my bird-watching skills and passion with my new obsession with avian phylogeny. Before going on to graduate school, I was desperate to get to South America and to see more of the birds I had met in the drawers at the MCZ. (There were very few tropical bird field guides in those days, so browsing through a museum collection was actually the best way to learn about the birds before actually seeing them in real life.) Intrigued by the Harvard graduate student Jonathan Coddington’s research using the phylogeny of spiders to test hypotheses about the evolution of orb-web-weaving behavior, I wanted to make a similar use of phylogeny to study the evolution of bird behavior.

At about that time, I met Kurt Fristrup, a Harvard graduate student, who had worked on the behavior of the flamboyantly orange Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock (Rupicola rupicola, Cotingidae) (color plate 5), one of the planet’s most amazing birds. Kurt suggested, “Why don’t you go to Suriname to map manakin leks?” In retrospect, this was one of the most consequential pieces of professional advice I ever received.

On a thin branch twenty-five feet high in the sun-dappled understory of a tropical rain forest in Suriname perches a tiny glossy black bird with a brilliantly golden yellow head, bright white eyes, and ruby-red thighs—a male Golden-headed Manakin (Ceratopipra erythrocephala) (color plate 6). He weighs about a third of an ounce (ten grams), or a bit less than two U.S. quarters. He has a short neck and short tail, giving him a compact body, but he has a nervous energy that belies his almost dumpy appearance. He sings a high, soft, descending whistled puuu and peers intently around, hyperaware of his surroundings. In moments, a second male whistles back from his perch in an adjacent tree, and then a third nearby. The male answers immediately. His social environment is obviously the focus of his keen attention. In all, there are five males clustered together in the forest. They are obscured from one another by foliage, but they are all within earshot of each other.

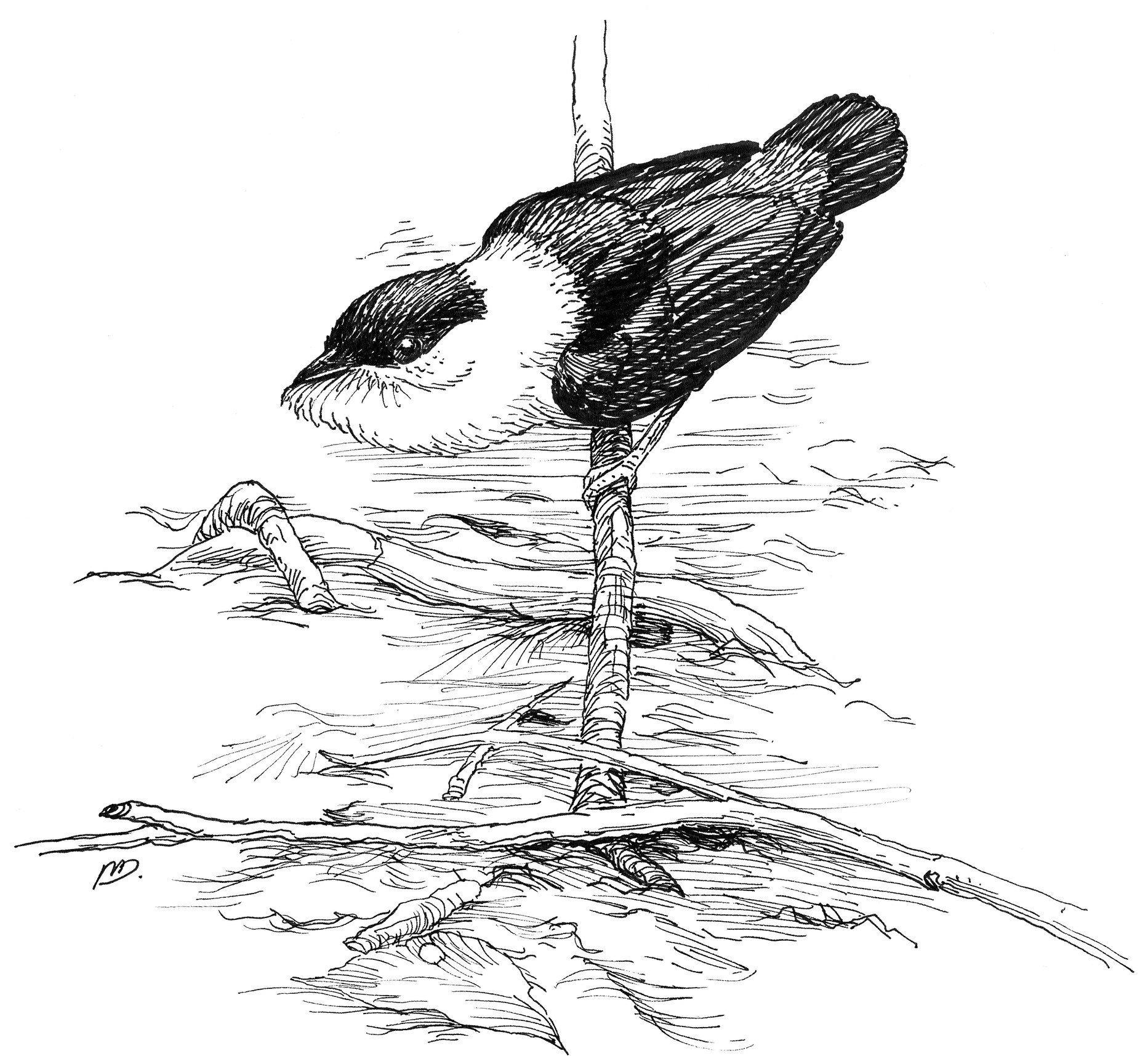

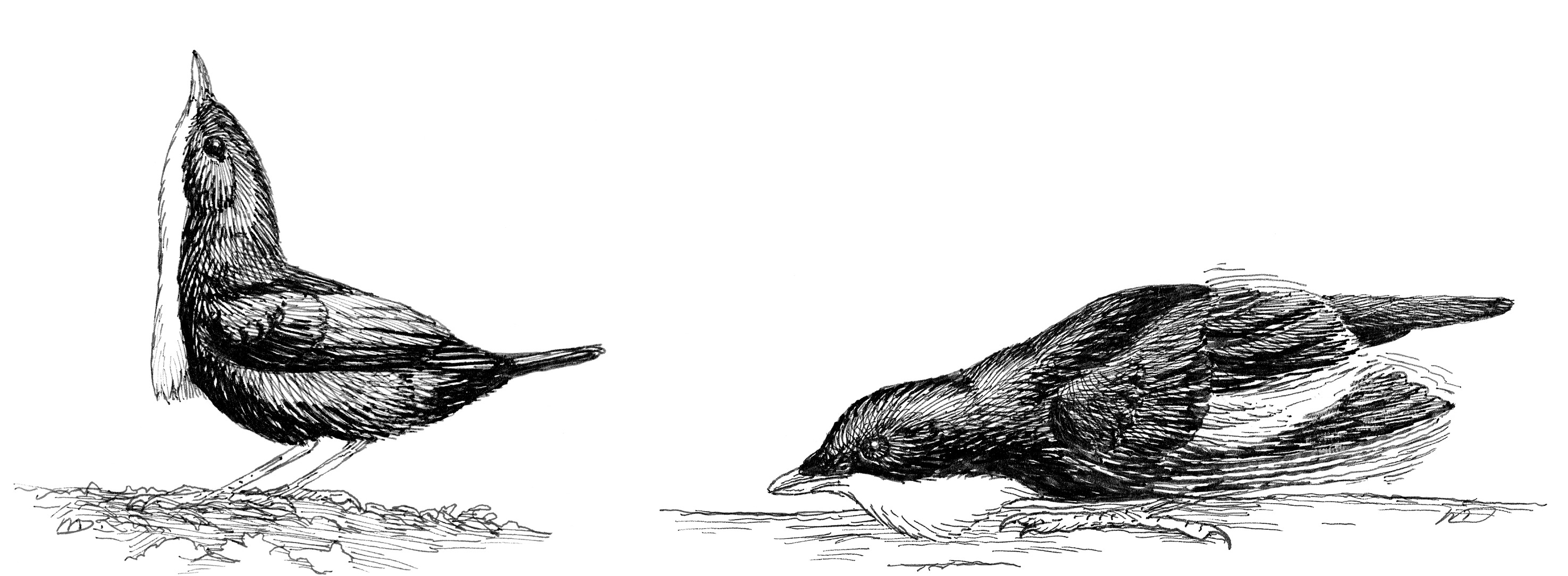

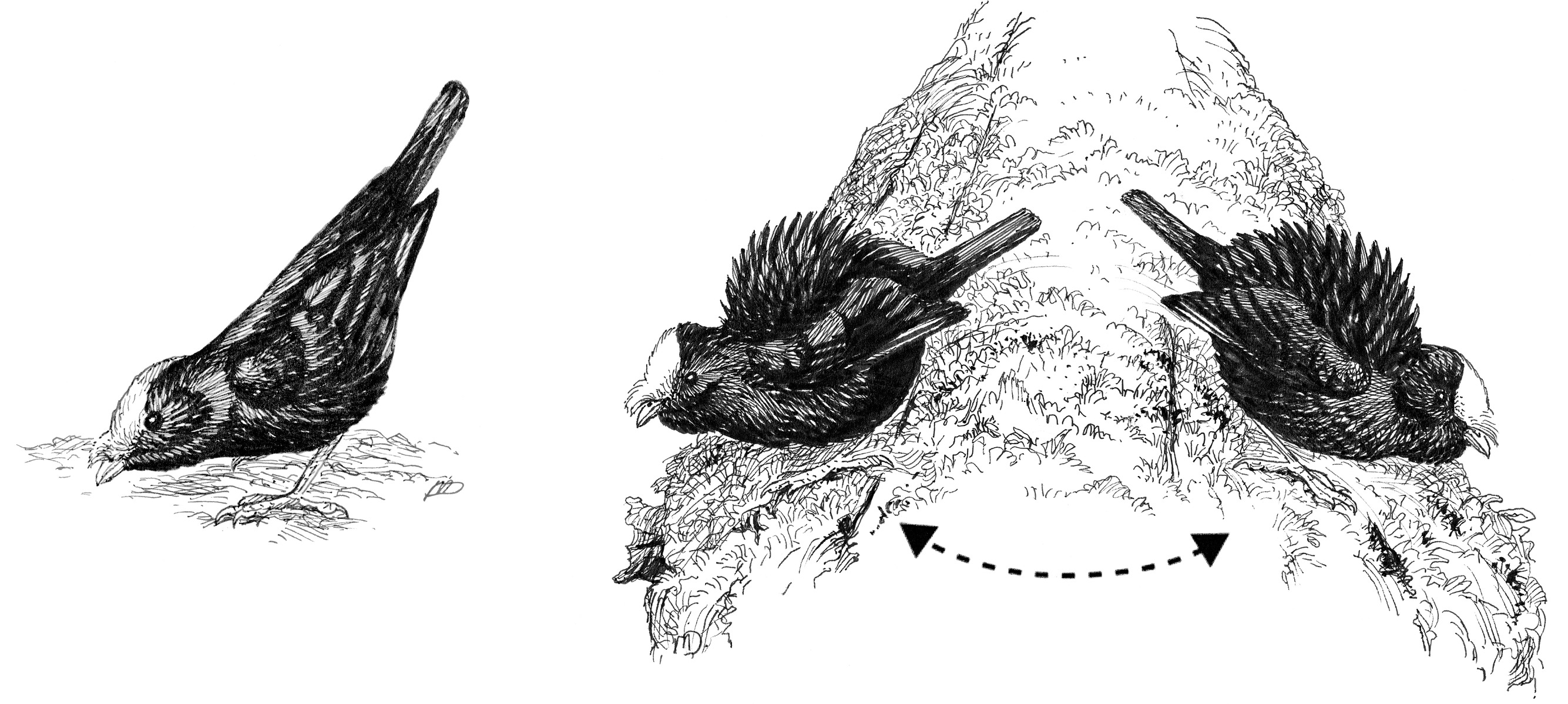

In response to the neighboring calls, the first male draws himself up into a statuesque upright posture with his light-colored bill pointing upward. After singing an energetic, syncopated, and raspy puu-prrrrr-pt! call, he suddenly flies from his perch to another branch twenty-five yards away. After a few seconds, he flies rapidly back to his main perch singing an accelerating crescendo of seven or more kew calls in flight. His flight path traces a subtle S-curve trajectory, first down below the level of the perch and then up above it. He lands on the perch from above while uttering a sharp buzzy szzzkkkt! Immediately upon landing, the male lowers his head, holds his body horizontal to the branch, and raises his rear up with his legs extended, revealing bright red thighs against his black belly, like a provocatively colored pair of breeches. He then slides backward along the perch in the tiny rapid steps of an elegant “moonwalk,” as if on roller skates. In the middle of the moonwalk, he flicks his rounded black wings open vertically above his back for a moment. After sliding backward for twelve inches along the branch, the male suddenly lowers and fans his tail, flicks his wings vertically again, and resumes his normal posture.

Moments later, the second male Golden-headed Manakin flies in and perches on another branch about five yards away. The first male immediately flies to join him, and they sit quietly side by side—but facing away from each other—in the dramatic upright posture. Intense, competitive, but mutually tolerant, the two males are deeply engaged with each other.

This scene is just a few moments in the bizarre social world of a Golden-headed Manakin lek. A lek is an aggregation of male display territories. Lekking males defend territories, but these territories lack any resources that females might need for reproduction other than sperm: no significant food, nest sites, nest materials, or other material assistance to the female. Golden-headed Manakins defend individual territories between five and ten yards wide, with two to five such territories grouped together. Leks are essentially sites where males put themselves on display in order to lure females to mate with them. Over the breeding season, individual females visit one or more leks, observe male displays, evaluate these displays, and then choose one of those males as their mate.

Lek breeding is a form of polygyny (one male with many potential mates) that results from female mate choice. In a lek-breeding system, females can select any mate they want, and they are often nearly unanimous in preferring a small fraction of the available males. So a relatively few males get to mate with a relatively large number of females. The skew in mating success is rather like the contemporary skew in income distribution. The most sexually successful males are very successful and account for half or more of all the matings, while other males will never have any opportunity to mate in a given year. Some males go their whole lives without mating.

The backward slide display of the male Golden-headed Manakin.

After mating, female manakins build nests, lay clutches of two eggs, incubate them, and care for the developing young entirely on their own without any help from the males, whose contributions to reproduction end with their sperm donations. Because females do all the work, they don’t depend on the males for anything, and their independence allows them almost total sexual autonomy. This freedom of mate choice has allowed extreme preferences to evolve; females only choose the few males whose behavioral and morphological features meet their very high standards. The rest will be losers in the mating game. Thus the aesthetic extremity of male manakins is an evolutionary consequence of extreme aesthetic failure, which results from strong sexual selection by mate choice.

Female manakins have been choosing their mates in leks for about fifteen million years. Over the course of time, the features they have preferred have evolved into an extraordinary diversity of traits and behaviors among the approximately fifty-four species of manakins distributed from southern Mexico to northern Argentina. Manakin leks are among nature’s most creative and extreme laboratories of aesthetic evolution. For me, they proved the perfect place to study Beauty Happening.

Inspired by Coddington’s revolutionary spider research and Fristrup’s helpful suggestion, I headed off in the fall of 1982 to the nation of Suriname, a small, culturally Caribbean, former Dutch colony in northeastern South America, for what turned out to be a five-month sojourn in search of manakins. In Suriname, I worked at the Brownsberg National Park, a fifteen-hundred-foot-high, table-topped mountain covered in tropical rain forest, which is just a few hours south of the capital city of Paramaribo, down red dirt roads. Within a couple days of observing my first Golden-headed Manakins, I also found the White-bearded Manakin (Manacus manacus). One morning while walking through the young secondary forest along the main road through the park, I heard a sharp snap within a shrubby thicket, which sounded like a tiny popgun or a toy firecracker. In the thick shrubs along the road edge, I spied a boldly plumaged White-bearded Manakin (color plate 7). The male of the species has a black crown, back, wings, and tail and bright white underparts that extend in a collar around his nape. Perched only a yard above the ground, this male gave a loud chee-poo call, which was quickly answered by another male a few yards away.

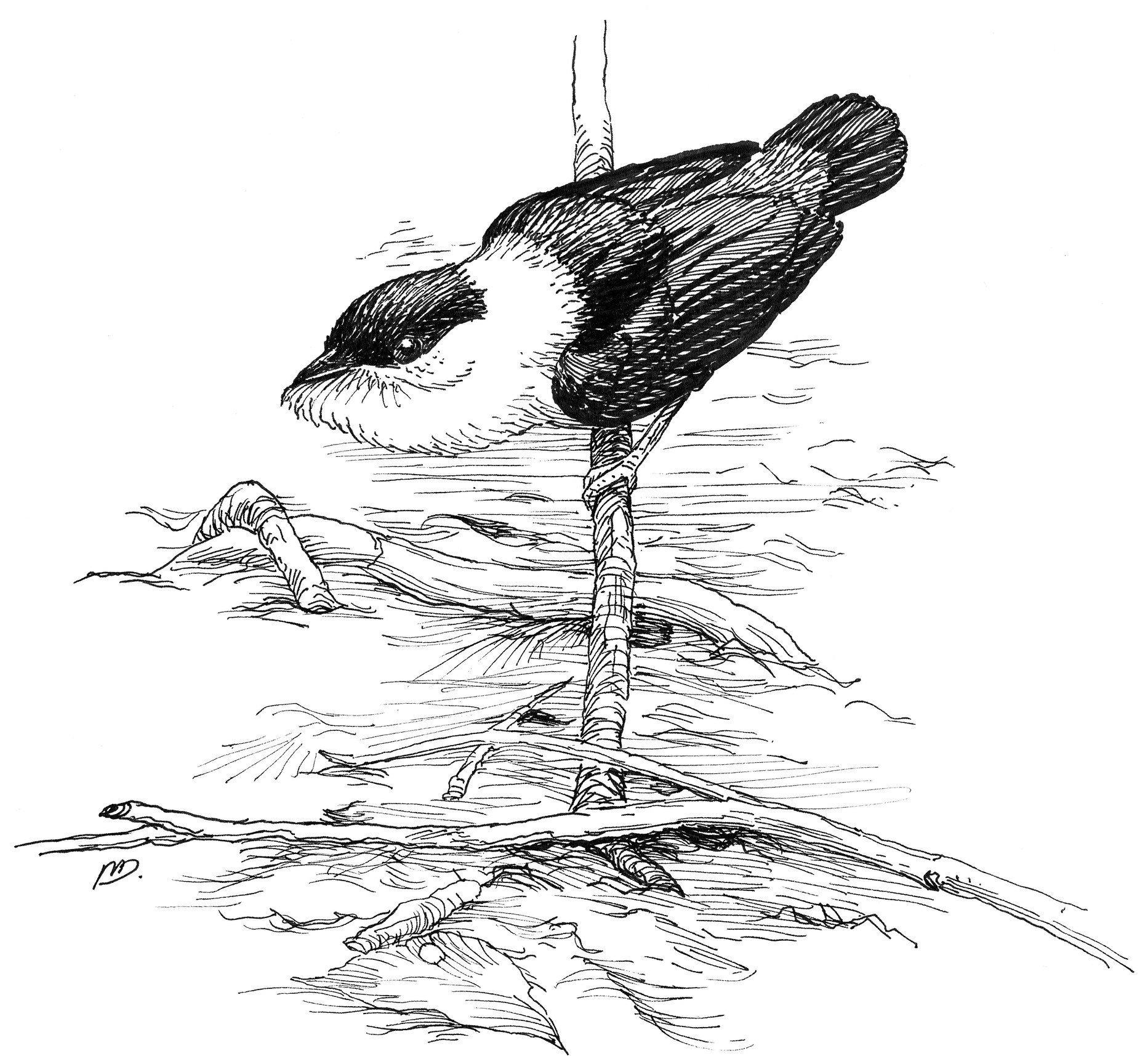

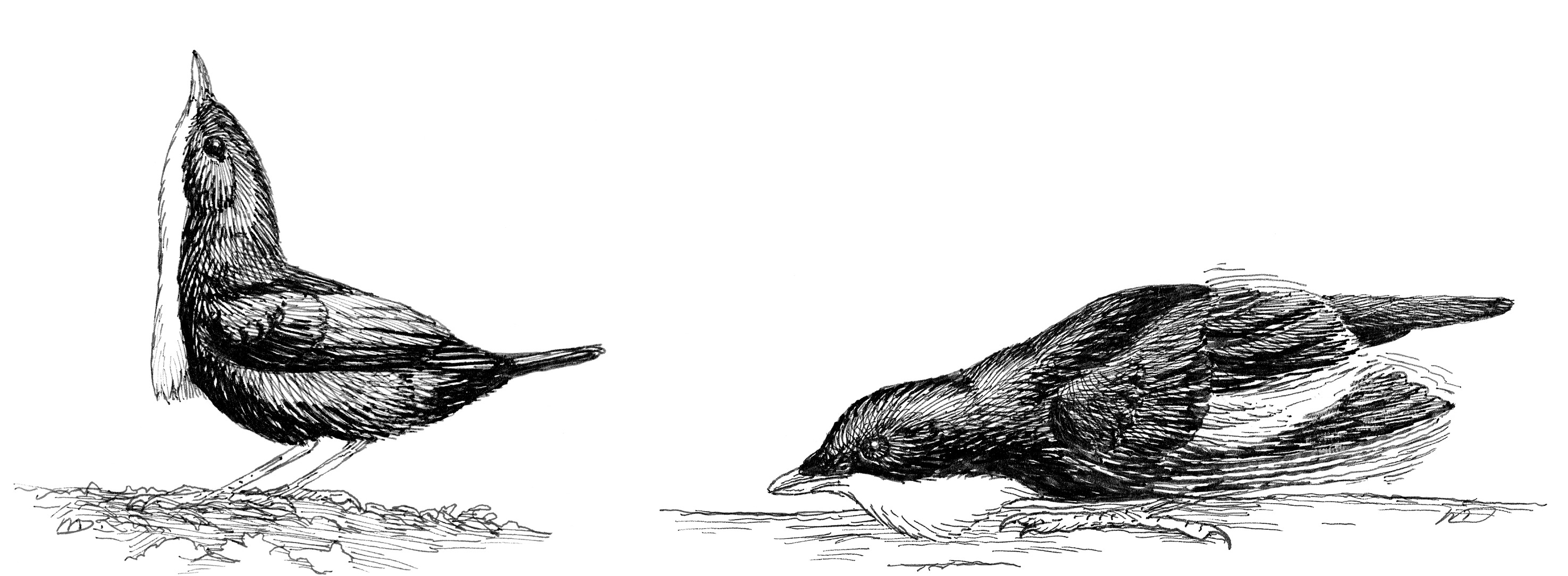

Unlike the Golden-headed, the White-bearded Manakin displays on and near the forest floor, and the males cluster closely together in tiny display territories within a few yards of each other. After I waited patiently for a few minutes, a flurry of displays suddenly broke out. The first male flew down to a small court—that is, a patch of bare dirt on the forest floor about a yard wide—and began to bounce rapidly back and forth between small saplings around the edges of the court. Each flight was punctuated by a sharp Snap! that is made by the wing feathers. When perched, his body was transformed. The previously smooth white feathers of his throat were now fluffed out and forward to form a puffy white beard that extended beyond the tip of his bill. Soon several males were all snapping and calling simultaneously. When perching, the males would occasionally make a sudden, explosive, and rapid series of snaps so quickly that they blurred together in a flatulent Bronx cheer. As suddenly as the excitement started, the wave of displays ended, and the lek quieted down to a few chee-pooos, with long waits in between.

Unlike the elegant flight and perch displays of the Golden-headed Manakins, the White-bearded Manakin displays are rowdy and rambunctious. The males are packed together, hopping and popping vigorously. White-bearded Manakin males are like buff gymnasts, executing short flights and rebounds with muscular precision.

Comparing the radically different display repertoires of just these two manakin species introduces the central dilemma of their aesthetic evolution. How did they evolve to be so different from each other? The true magnitude of this mystery emerges when we realize that every one of the approximately fifty-four species of manakins has evolved its own distinct repertoire of plumage ornaments, display behaviors, and acoustic signals; that is fifty-four distinctive “ideals” of beauty. Because nearly all species of the family are lekking, we can be confident that all manakins evolved from a single lekking common ancestor, which, we can infer from time-calibrated molecular phylogenies, lived about fifteen million years ago. So, why did the females of each manakin species evolve such highly diverse mating preferences—their own Darwinian standards of beauty? And how did this aesthetic radiation occur? Learning the answer requires that we explore the history of beauty through the Tree of Life.

A male White-bearded Manakin landing on a sapling on his display court with his throat feathers erected.

There is a reason manakins are such a good example of the evolution of beauty, and it has to do with family life. Over 95 percent of the world’s more than ten thousand bird species are raised by two attentive, hardworking parents. But not manakins. The British ornithologist and pioneering manakin man David Snow first proposed an evolutionary explanation for their distinctive breeding system in his enchanting 1976 book, The Web of Adaptation. The book is an evocative account of his and his wife’s adventures studying lekking manakins and cotingas in Trinidad, Guyana, and Costa Rica. (I read the book with great excitement when I was in high school, and my still vivid memory of it was one reason why I responded so positively to Kurt Fristrup’s suggestion to go study manakins in Suriname.) Snow hypothesized that eating a diet consisting largely of fruits, as manakins do, can rearrange an animal’s family life and unleash a cascade of effects on its social evolution.

Imagine that you eat insects for a living. You are probably thinking that this would not be an easy life, and you would be right. Insects make themselves difficult to find, prickly, hard to handle, distasteful, and sometimes even toxic. Living on a diet of insects is hard work quite simply because insects do not want to be eaten. That’s why raising a family on insects is almost always a two-bird job.

By comparison, feeding mostly on fruit is like a dream—a land of milk and honey—because fruit wants to be eaten. Fruits are highly caloric, nutritional bribes created by a plant to entice animals to swallow, transport, and deposit their seeds far away from the parent plant. Fruit is the plant’s way of seducing mobile organisms to do its bidding and disperse its young. As a result, fruit advertises itself, is easy to find, often easy to handle, and abundantly available. Fruit-eating animals, like manakins, oblige the plant by regurgitating and defecating the seeds from the fruits they eat as they move through the forest.

If the living is so easy for fruit eaters, why don’t they just use both parents to raise lots more kids? The problem, Snow proposed, is predation at the nest. Lots of chicks means lots of activity to attract predators and therefore lots more risk of losing the whole brood. Snow argued that limiting the clutch size—that is, the number of eggs laid in each bout of breeding—to two allows a single female to raise the family safely and successfully all on her own. By feeding mainly on abundant fruit, a single female manakin can build her own nest, lay the eggs, incubate the clutch, feed the young until fledging entirely by herself, and reduce predation at the nest.

Snow hypothesized that lek display in manakins evolved when an evolutionary shift in diet to fruit meant males were “emancipated from parental care.” Females used their capacity for mate choice to select among available mates, and the result was tremendous aesthetic elaboration and diversification of male display. Of course, Snow’s scenario for how this would happen was incomplete because he did not yet have an understanding of sexual selection. We now know that unconstrained opportunities for mate choice will lead to the evolution of selective mate preferences—that is, pickiness.

Lekking birds feature so prominently in this book because lek-breeding systems create the strongest sexual selection forces in nature and give rise to the most aesthetically extreme—and often enchanting—forms of sexual communication.

I was excited by my sightings of Golden-headed and White-bearded Manakin leks at the Brownsberg, and I did start to try to map out the male territories within the leks, as Kurt Fristrup had suggested. However, I was much more intrigued by the actual dances the males did than by the spatial relationships of their territories. Besides, David Snow and Alan Lill had already published extensively about these two common and broadly distributed species. I wanted to focus on manakins that hadn’t been as well studied.

My real intellectual goal was to find the virtually unknown White-throated Manakin (Corapipo gutturalis) and the White-fronted Manakin (Lepidothrix serena), which were both reported to occur at the Brownsberg. The male White-throated Manakin is a deep, glossy iridescent blue-black color with an elegant snowy-white throat patch that extends down the breast in a pointed V-shape (color plate 8). The species was so poorly known that it had been left out of François Haverschmidt’s Birds of Surinam, published in 1968, but birders had recently reported it from the Brownsberg. In contrast, the male White-fronted Manakin is a velvety black with a royal-blue rump, a snowy-white forehead, a banana-yellow belly, and an orange-yellow spot on its black breast (color plate 9). Very little was known about the species in the wild.

Finding a specific bird species among the hundreds of species in a tropical rain forest is a real challenge. At the time, the songs of the White-fronted and White-throated Manakins had not been described for science, and no recordings were available. The only way to find these birds was to persistently bird-watch my way through the entire avifauna until I found them. This method consisted of going out every day, listening for new bird songs, tracking them down, identifying them, learning them, and adding them to my growing mental catalog of bird sounds that were not the manakins I was looking for. Of course, this was still spectacularly exciting, because virtually all the birds were new to me. Along the way, I would find legendary neotropical birds like the Ornate Hawk-Eagle (Spizaetus ornatus), the Crimson Topaz (Topaza pella) hummingbird, the Variegated Antpitta (Grallaria varia), the Sharpbill (Oxyruncus cristatus), the White-throated Peewee (Contopus albogularis), the Red-and-black Grosbeak (Periporphyrus erythromelas), and the Blue-backed Tanager (Cyanicterus cyanicterus). But the checklist of the birds of Brownsberg listed over three hundred species. So, if I wanted to find the two manakins that were my focus, I had my work cut out for me.

At the end of the first week, I found my first territorial male White-fronted Manakin just off a trail on the flattop of the Brownsberg. The advertisement song of this species turned out to be one of the least impressive of all the manakins. It is a single, simple whreeep note with the casual, rolling, froggy richness of a brief toot on a police whistle. In my notes from that first day of discovery, I described the song as a “short, sporadic farty trill.” The display repertoire of the White-fronted Manakin turned out to be relatively simple, too—on the vanilla end of the diversity in manakin aesthetics. The main male display consists of a series of to-and-fro flights about two feet above the ground, which take him back and forth between thin, vertical saplings that surround a central “court” about a yard wide.

These display flights were of two types. Some were direct “beeline” flights between saplings, with the bird flipping around in midair so that when he landed he would be facing inward toward the court for his return flight. The series of beeline flights would continue for up to twenty seconds. During these displays, the male sometimes perched momentarily on a sapling with his azure-blue rump and white fore crown showing boldly. In the alternative “bumblebee” flight displays, the male flew back and forth between two saplings, springing off the branches as soon as he touched them and hovering in the air with his body held nearly vertical, his wings beating in a rapid whirr. This gave the rather eerie visual impression of a multicolored ball hovering between the saplings at knee height above the ground.

In many days of observation, I saw two probable female visits. I say “probable,” because all young male manakins have green plumage like the females. In neither case was I able to observe a copulation, which would have confirmed the sex of the visitor. Marc Théry made later observations of the same species in French Guiana. He observed that females follow the male around the court during several to-and-fro flights and then alight on a small horizontal perch on the court edge. The male then flies up and mounts the female in copulation.

After starting my observations of the White-fronted Manakin, I alternated mornings of watching them at their leks with the search for other manakin species elsewhere in the park. I soon found the male White-crowned Manakin (Dixiphia pipra), which is coal black with a bright white crown and bright red eyes, and I observed it for several days. It took a little longer to find the Tiny-tyrant Manakin (Tyranneutes virescens), a truly diminutive and amazingly nondescript olive-green bird with an oft-hidden, tiny central yellow crown stripe that weighs in at only seven grams—or about as much as one and two-thirds teaspoons of salt. The male sings a soft, hiccuping little trill from a thin branch about three to five yards high. The first time I found a male singing, he was so motionless and inconspicuous that it took me ten minutes to spot the bird, even though he was perched in plain sight.

I enjoyed my sightings of these birds, but because the display behaviors of both the White-crowned and the Tiny-tyrant Manakin had already been described by David Snow in the early 1960s, I was still determined to find the mysterious White-throated Manakin.

The courtship of the White-throated Manakin was only known from a brief note published in the British ornithological journal the Ibis in 1949, which described a single anecdotal observation by T. A. W. Davis. One morning in nearby British Guiana, Davis saw a group of males and “females” consorting together. (Davis did not consider whether any of these green “females” could actually have been young males.) He observed some remarkable male displays and even saw a pair copulating on a mossy fallen log on the forest floor. The displays included a posture with the bill pointed upward, revealing the white throat, and another with the wings held open and the male moving across the log in a “slow undulating crawl.” No one had ever reported a display like this in any other manakin species, and I was desperate to see it for myself.

One day in mid-October, I descended the slopes of the mountain to lower-altitude forests along the Irene Val Trail, named for the lovely Irene Waterfall. It was an active morning in a very birdy tropical forest. At one point, I heard a whooshing sound immediately by my head. At first, I thought I might have been dive-bombed by a hummingbird, but when I looked up, I was surprised to see a male White-throated Manakin perched on a branch immediately above the trail. I then realized that I had just stepped over a large log that was lying in the middle of the trail. Intrigued by the possibility that I had interrupted him in mid-display, I backed off the trail to use the forest foliage as a temporary blind. Immediately, the male flew back down to the log in the trail with a rapid flurry of whirring wings, bounding leaps, popping noises, and squeaky calls. The first male was soon joined by two other adult males and two immature males—which were identifiable by their mostly green, female-like plumage and black, Zorro-like face masks. Within the space of a few minutes, I saw more White-throated Manakin displays than T. A. W. Davis had in 1949, and I knew that I had a great scientific opportunity ahead. In the months that followed, I would spend dozens of days observing the White-throated Manakins and, in the process, get totally hooked on studying lek behavior.

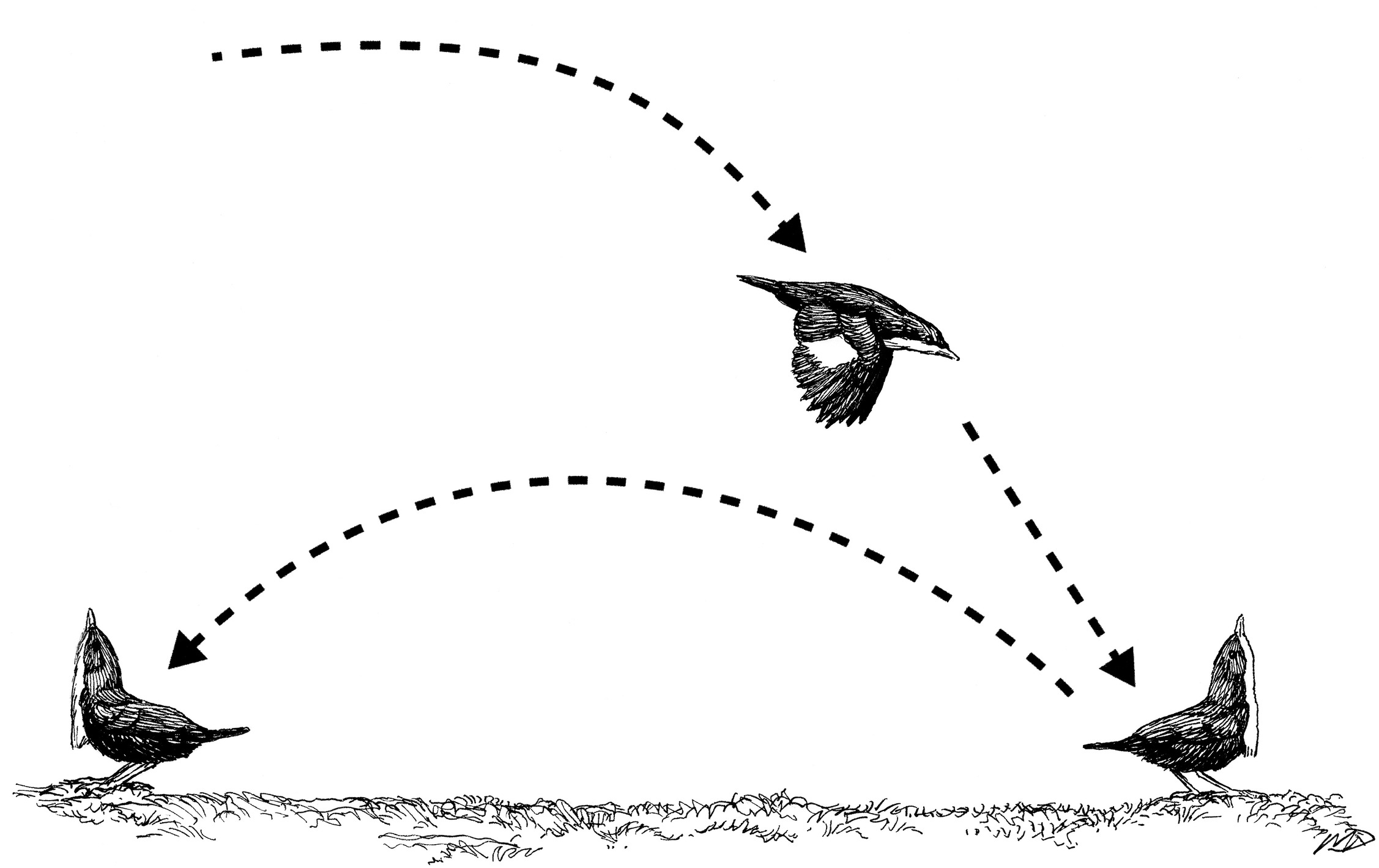

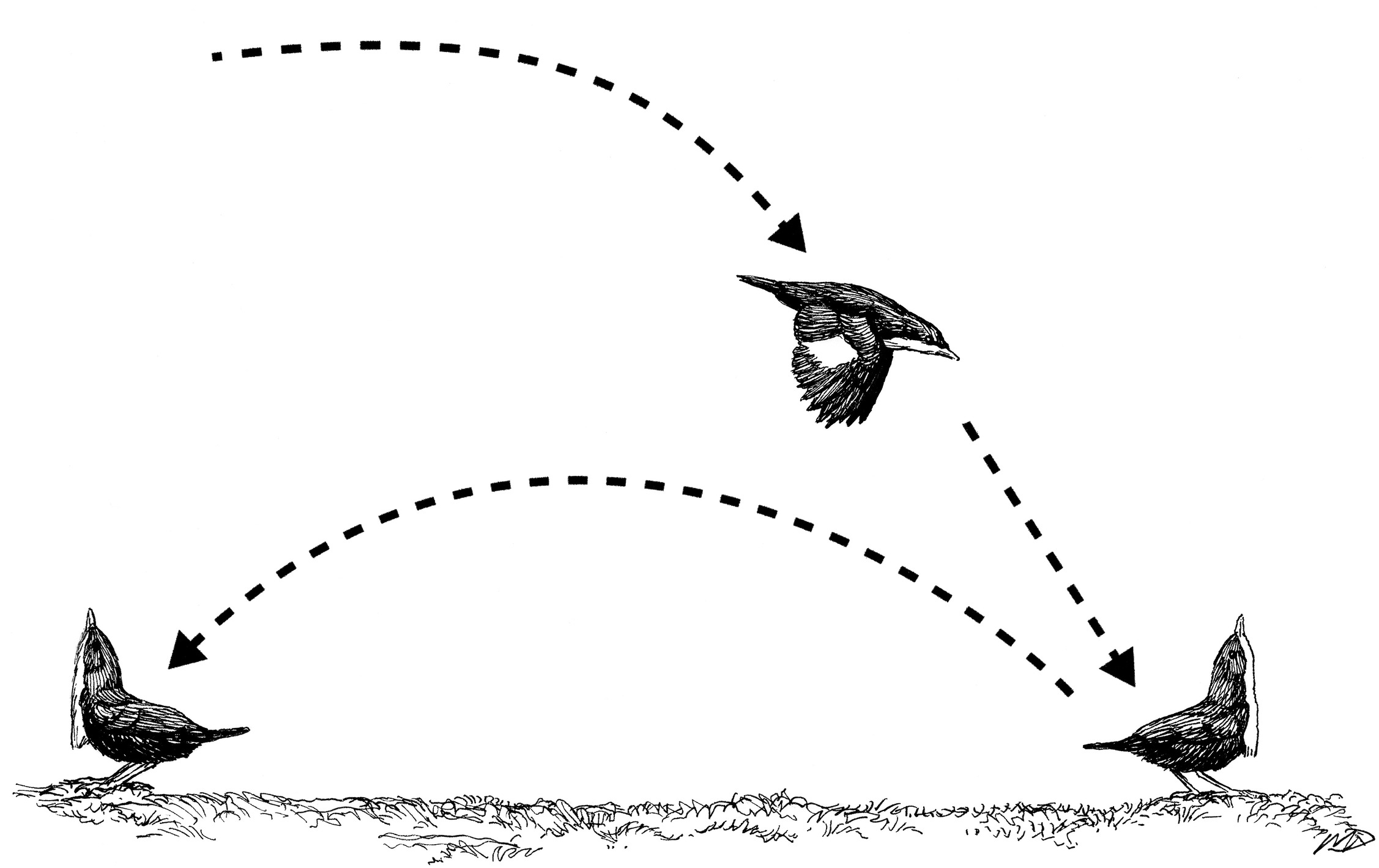

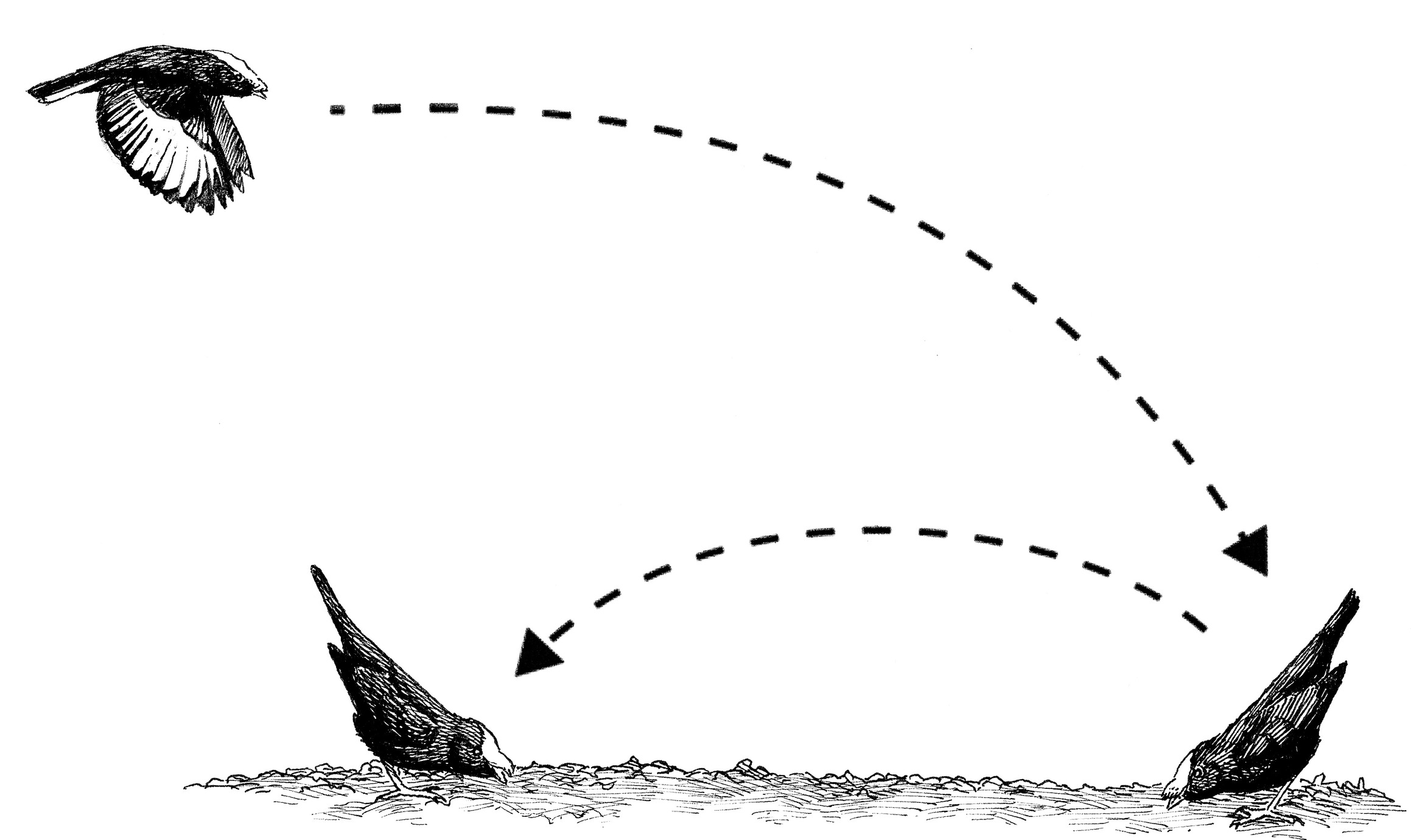

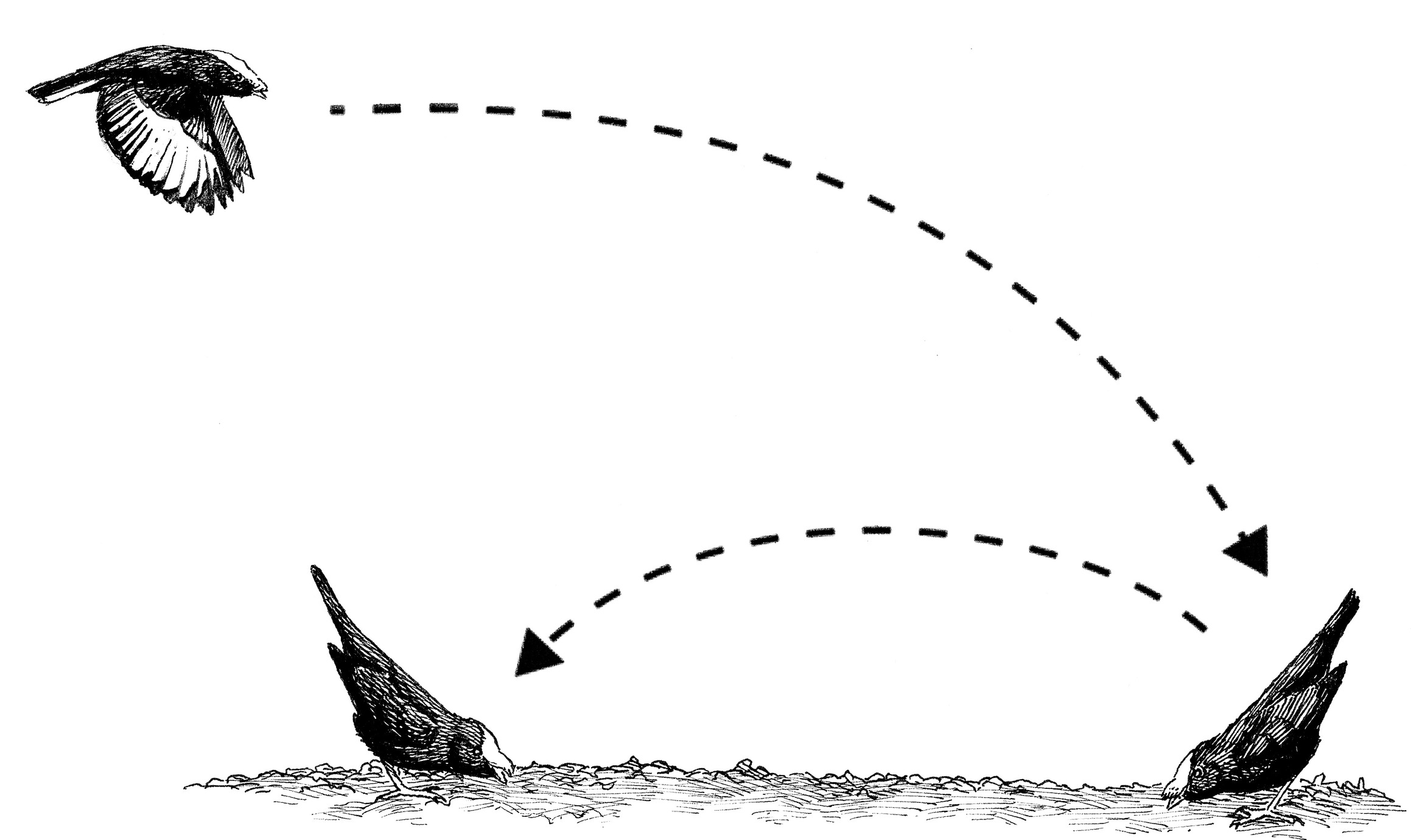

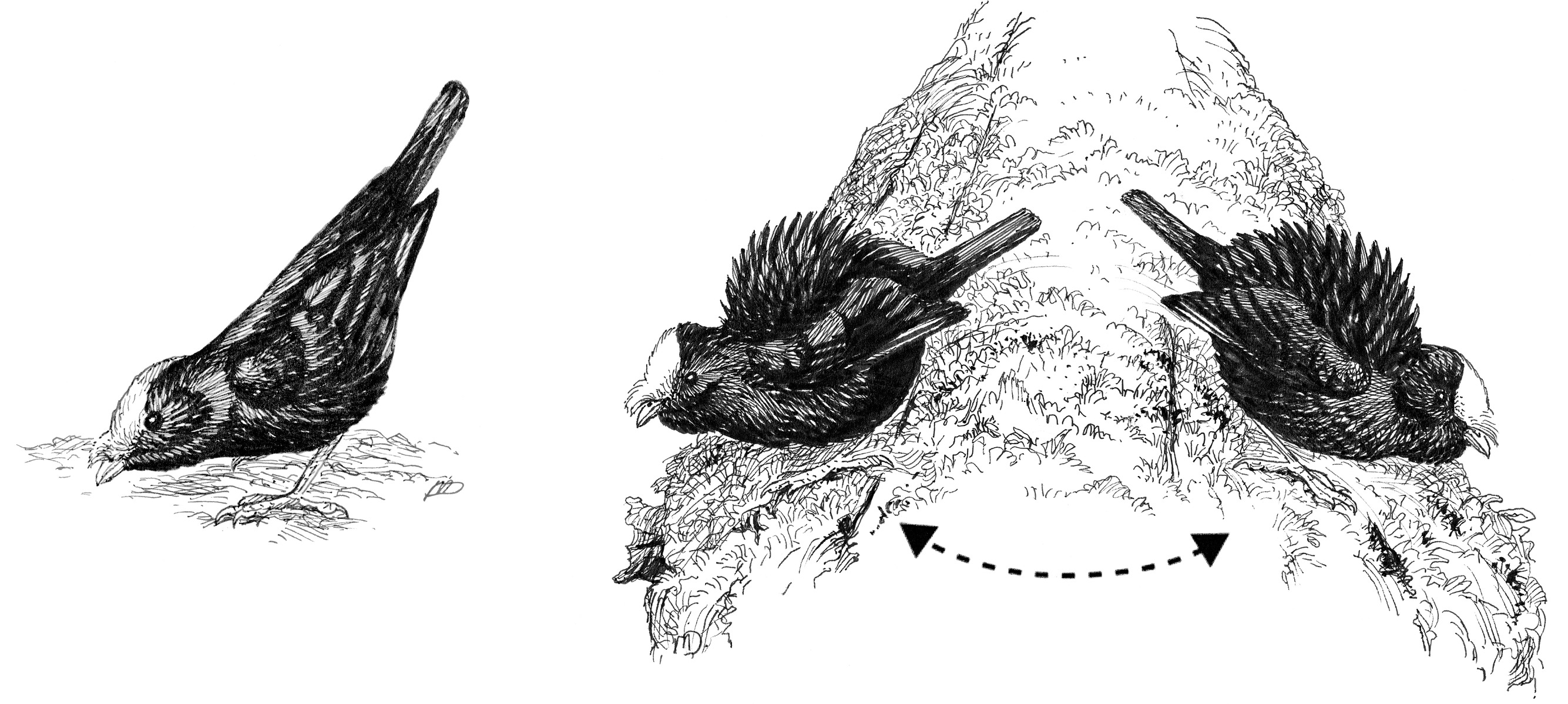

Although manakin display repertoires are usually dramatic, the displays of the male White-throated Manakin had a degree of complexity that was completely new to me, comprising an extraordinarily rich array of behavioral elements. His advertisement song is a high, thin, whistled seeu-seee-ee-ee-ee, sometimes shortened to seeu-seee. He sings this call quite calmly, only a few times a minute at most, from a perch two to six yards high. The astounding acoustic and acrobatic tour de force in his display repertoire is the log-approach flight display. Starting from a perch five to ten yards away, the male flies toward the log, giving a crescendo of three to five insistent seee notes as he goes. In the air, about a foot above the log, the male suddenly stalls in mid-flight with a prominent flap of his wings, producing a sharp pop, and drops to the log. Immediately upon landing, he rebounds into the air, turns around in mid-flight, gives a squeaky, raspy, cranky-sounding tickee-yeah call, and lands about a foot and a half down the log. He lands instantly frozen in a crouching, bill-pointing posture with his beak held straight aloft and his pointy, V-shaped snowy-white throat patch exposed. I also observed an alternative log approach—the “mothlike flight” in which a male fluttered slowly, undulatingly down to the log with a series of labored, exaggerated wing flaps, all the while holding his body in a vertical position.

Once on the log, the glossy blue-black male performs additional displays. Sometimes, he crouches and lowers his beak to the log, holding the wrists of the wings slightly shrugged above his back, while running back and forth across the log. In the “wing-shiver” display, he holds his body horizontal and opens and closes each wing in rapid, alternating succession, flashing the brilliant white patches that are concealed when his wings are closed. With each alternating wing opening, the male shuffles the foot on the same side to creep backward along the log. This is Davis’s “slow undulating crawl.”

Each male displays at a few logs within a territory about twenty yards wide. The display excitement within a male’s territory is occasionally enhanced by the arrival of a rowdy, traveling band of two to six males of mixed age that display together and with the territory holder. The groups include both adult males that may have their own territories but have temporarily joined the wandering, group display and young males in various stages of preadult plumage, who apparently do not hold territories. These group displays are not coordinated but more like a highly competitive form of rabble-rousing. Males vie for access to the same display log, performing a rapid flurry of log-approach displays one after another and frequently displacing each other from the log. During the competition for control of the log, males “strafe” each other by flying low over the log and producing only a mechanical pop just over the male on the log, right at the nadir in flight. The result can be an exciting flurry of pops and log-approach calls in rapid succession by different males: POP-tickee-yeah—POP—POP-tickee-yeah—POP!

The log-approach display of the male White-throated Manakin.

During months of observations at White-throated Manakin logs, I saw only two female visits. One or two green-plumaged individuals perched on a log and intently observed a displaying male while he performed a series of log-approach displays or wing-shiver displays. Interestingly, when performing the wing-shiver display for a visiting female, the male turned his back and crawled backward toward the female. Even during the bill-pointing posture, which displays his bright white throat, he turned his back on the female. With his beak held high, he often peered nervously over his shoulder to monitor how the visiting female was responding to his display. I myself saw no copulations. But both T. A. W. Davis in British Guiana back in the 1940s and Marc Théry in French Guiana many years later documented that copulation takes place on the log after a series of these displays, with the male mounting the female directly on the rebound from a log-approach display.

The bill-pointing (left) and wing-shiver (right) displays of the male White-throated Manakin.

In November 1982, an unusual, and unusually talented, birder arrived at the Brownsberg. Tom Davis was a lanky, six feet eight, foulmouthed telephone company engineer and legendary New York birder from Woodhaven, Queens, with great identification skills and an audiophile’s obsession for recording bird song in the field. Through a series of birding vacations, Tom had become an outstanding expert on the birds of Suriname. When Tom arrived, he told me that during the previous year, while sitting on a bench overlooking the forested valley where he had been birding for so many years, he had discovered a spectacular above-the-canopy flight display by White-throated Manakins.

In our very first day together in the field, Tom took me to a viewing point from which he was able to show me this novel flight display, which took place more than fifty to a hundred feet above the tallest trees in the forest. After waiting for about thirty minutes, I saw a male ascending skyward while vocalizing an emphatic series of SEEEE…SEEEEE…SEEEEE notes that were even louder, more intense, and more emphatic than the similar notes I’d heard at the logs during log-approach displays. The ascending male flew in a bizarre fluffed-out posture looking rather like a black-and-white cotton ball. After the male reaches the apex of his flight, he suddenly plummets back down into the forest. In the previous year, Tom had made a tantalizing observation; some of the above-the-canopy flight displays end with a loud, mechanical Pop! note after the male disappears back into the forest.

In the weeks that followed, I was able to piece together the entire display sequence. One day during observations at a display log, I heard the especially intense version of the SEEEE calls that the male makes during his above-the-canopy flight from overhead and suddenly saw the male come careening downward through a hole in the forest canopy toward the log and perform a full log-approach display. Only then did I realize that I should have been looking up! Within a few days, I made multiple observations of males plummeting down through the forest canopy to the log after their above-the-canopy flights.

I am sure that I would never have discovered these flight displays by myself, given that I was spending all my time inside the forest at the display logs themselves. So, Tom Davis’s fantastic observations were essential to the story. The specific function of this especially extravagant behavior—advertising to females over many acres of forest?—remains enigmatic.

My ornithological Wanderjahr in Suriname was a transformative personal and intellectual experience. I had made it out of the university to a distant and exotic corner of the world, and I had thrived. During my five months there, I had used my birding skills to observe hundreds of species of birds. I came away with unique scientific observations of previously unknown lek behaviors, which were significant enough to constitute my first scientific papers, published a few years later in the canonical ornithological journals the Auk and the Ibis. I had also made good progress on devising a doctoral project on the evolution of manakin behavior.

The next year, I had the opportunity to return to South America to work as a field assistant to a Princeton graduate student, Nina Pierpont, who was studying woodcreeper ecology at Cocha Cashu—a remote, Amazonian field station in southeastern Peru. My research at Cocha Cashu proved to be critical to my future life, for it was there that I met Ann Johnson, a Bowdoin College student who was working as an assistant for a Princeton undergraduate student, Jenny Price, on the social behavior of White-winged Trumpeters (Psophia leucoptera). Ann and I became sweethearts that summer, and we have been partners ever since. Ann is a producer and cinematographer of nature and science documentaries for television. We have three sons.

In the fall of 1984, I started graduate school in evolutionary biology at the University of Michigan. Inspired by the diversity and complexity of manakin displays from Suriname, I proposed for my dissertation a grand, comparative analysis of the evolution of manakin behavior across the entire family. I wanted to use manakin phylogeny—their family tree—to study the evolution of manakin lek display behavior. This emerging scientific field combined phylogeny with the study of animal behavior, called ethology, into a vibrant new discipline—phylogenetic ethology. The goal was to investigate the evolution of behavior comparatively through its history. Although I didn’t realize it at the time, this was my first step into the study of aesthetic radiation.

During my first year in graduate school, my office mate, Rebecca Irwin, introduced me to the classic work of Ronald A. Fisher and to the revolutionary new papers on mate choice by Russell Lande and Mark Kirkpatrick. This was my first exposure to the science of mate choice and to the deep intellectual conflicts between the aesthetic/Darwinian and the adaptationist worldviews. But even then I could sense that the open-ended and arbitrary qualities of the Fisher hypothesis looked a lot more like how nature worked than the honest signaling theories did.

I was desperate to get back to South America and continue with my manakin fieldwork. I did not know where to go, but I was particularly intrigued by the idea of going to the Andes, which would provide so many great birding experiences. So, for my first summer in graduate school in 1985, I proposed that Ann and I would conduct field research in the Ecuadorean Andes to discover the unknown lek display behavior of the nearly mythical Golden-winged Manakin (Masius chrysopterus). I had no better justification for the research than the fact that the bird was entirely unknown. I certainly did not tell my advisers or the grant agencies that I had chosen this bird in particular because it was beautiful and happened to live in the Andes, where hunting for it would be so birdy, fun, and rewarding. But thanks in part to my new track record of published manakin display descriptions, I managed to get a few small grants to fund this high-risk project. Even the local camping outfitter, Bivouac in Ann Arbor, agreed to subsidize the purchase of the camping equipment that we would need for the fieldwork, which helped make my few dollars go further.

By any measure, the Golden-winged Manakin is a strikingly gorgeous bird (color plate 10). The male’s plumage is mostly velvety black with a brilliant, plush yellow crown that extends slightly forward in a brushy crest over the beak, like a 1950s greaser hairstyle. The hind crown is brilliant red in the populations located on the east slope of the Andes and reddish brown in populations on the west slopes. On either side of the crown, the male sports two tiny, black, feathery horns. However, the truly stunning features of the male’s plumage are usually discreetly hidden. The wing and tail appear completely black when the bird is perched. But once in flight, the inner vane of each wing feather is revealed to be a vivid golden yellow, the same color as his crown. As we would discover, the sudden golden flash of his wings in flight is a major feature of the male’s courtship display, producing a visual effect that is as breathtaking as it is unexpected.

When Ann and I arrived in Ecuador, all that we knew about this bird came from what we had learned from fifty-year-old museum specimens. In 1985, there were no recordings of the Golden-winged Manakin in the collections of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology or the British Library of Wildlife Sounds, so we didn’t know what the bird sounded like. We also knew nothing about its breeding season, because this was among the many things completely unknown about the species.

We started our search in Mindo, a little town on the western slopes of the Andes at sixteen hundred meters in altitude, to the west of the capital of Quito. Mindo has since become a bustling ecotourism destination, but in 1985 it was a sleepy village with only a few dozen houses lining its mud streets. The forests around Mindo, however, were filled with diverse birdlife. We were thrilled to find Golden-winged Manakins foraging for fruit among flocks of brilliant Tangara tanagers. But we were unable to find any territorial males or any evidence of song or display activity. When asked by the curious locals if we had found the bird we were looking for, we had to explain, “La epoca no está buena.” It’s not the right season. Of course, we had no idea what the right season was.

After a month in Mindo without success, we got a great tip from an expatriate American ornithologist and bird artist, Paul Greenfield, who would later co-author the excellent Birds of Ecuador with Robert Ridgely. Paul had recently been birding along a mini railway line that ran parallel to the Colombian border from the north Andean town of Ibarra down to San Lorenzo on the Pacific coast. In the cloud forest around the tiny settlement of El Placer, he had seen plenty of Golden-winged Manakins. Perhaps, he suggested, if we went to a new locality with different geography, altitude, and weather conditions, it would be breeding season there, and we would be able to find the displaying males we were looking for.

We decamped to El Placer—literally “Pleasure”—via a train that consisted of a single car, like a city bus with small-gauge railroad wheels. This one car made a single round-trip to the coast and back each day. The “town” of El Placer was really just a collection of about ten rough-hewn, tin-roofed plank houses for the families of the workers who maintained that stretch of the railroad track. Besides the houses there was nothing in El Placer except an empty school, a railroad company office that doubled as a small store, and a few muddy footpaths into the surrounding forest.

El Placer must surely rank among the rainiest places on earth. It rained or drizzled continuously throughout the six weeks we were there. Even at the quite low altitude of five hundred to six hundred meters, the forest was very cool and mossy. The forest was second-growth cloud forest that had regenerated since the construction of the railroad decades before. We found a beautiful community of birds there, including Golden-winged Manakins, on the very first morning.

The first Golden-winged Manakin we saw was perched calmly on a branch about six feet above the ground, inside the dense mossy forest. In these very low light conditions, his velvety black plumage was like a light sponge, but his golden crown was brilliantly visible. He uttered a brief, low, raspy, frog-like nurrt call about three times a minute, a vocalization that was so underwhelming that we could easily have passed it off as the occasional call of a frog or insect. Between displays, male manakins often look like idle workers waiting out a long shift at a rather boring job. So, this male’s quite sedentary and indolent attitude was an excellent indication that he was on territory. My hunch was soon confirmed when we heard and located a second calling male about twenty meters away across the trail. This was clear evidence of a lek with multiple males and a great find after our weeks of fruitless observations in Mindo.

Given the unpredictability of wild bird behavior, you can never really know if the first moments of observation will be your last or the start of months of subsequent study. So you must always proceed as if the first sightings are the only opportunities you will ever have. We immediately deployed tape recorders and notebooks to record the behavior and songs of the two Golden-winged males, noting the qualities of the song, the rate of counter-singing between them, and the positions of their song perches.

After an hour or so, I heard a remarkably familiar sound coming from the area of the first singing male. It started with a high, thin descending whistle and ended with an accelerated and syncopated riff—like seeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee-tseet-tseee-nurrrt! I was immediately reminded of the log-approach display flight song of the White-throated Manakin from Suriname. The similarities were so strong that I became confused. We were thousands of miles away from the range of the White-throated Manakin in northeast South America; how could this be? The unexpected, even unimaginable solution to this conundrum would soon become clear, but in my mind there was still a lot of resistance to realizing it.

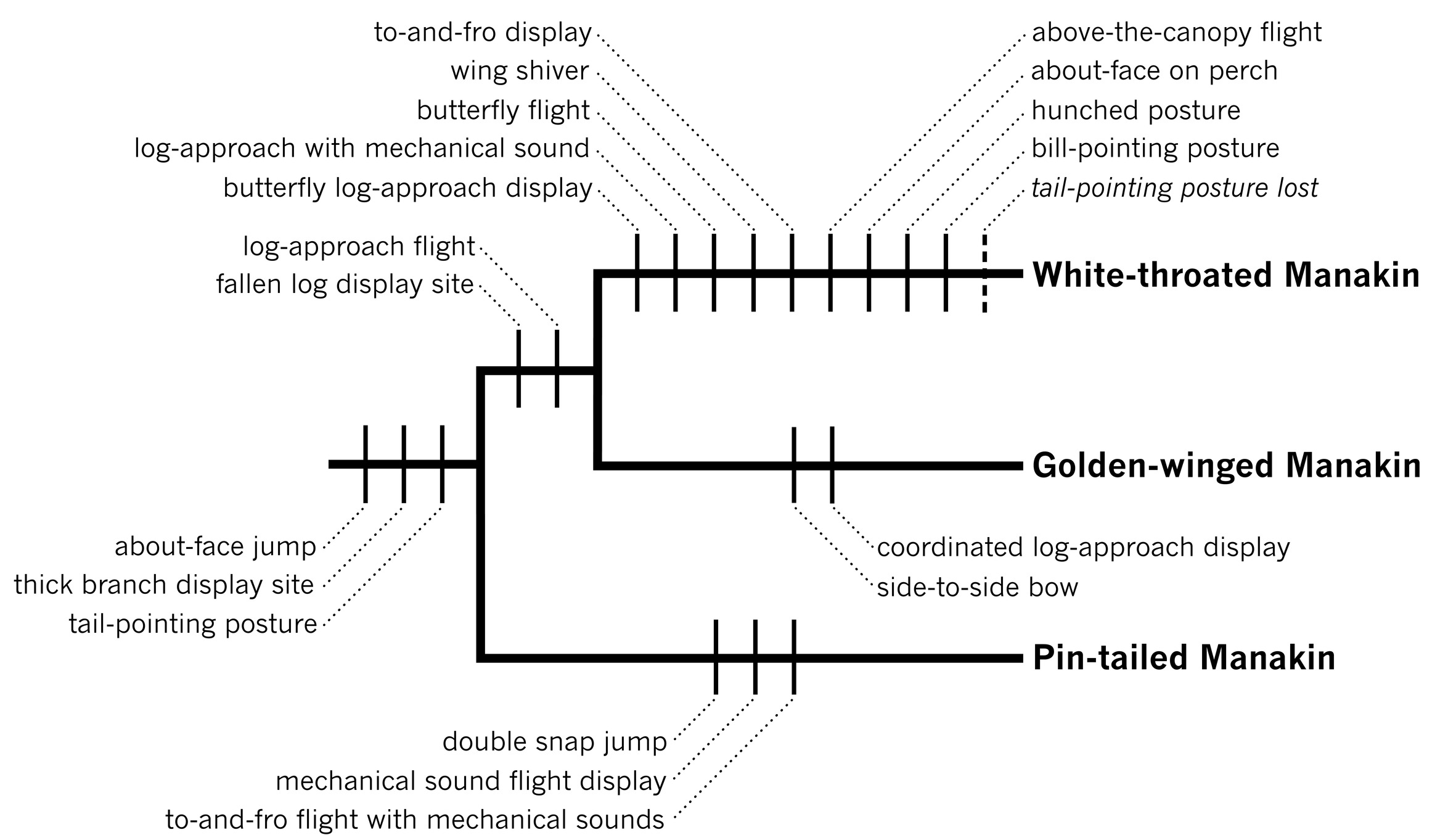

I returned to watch the first male Golden-winged Manakin in his territory, and what I observed over the next few minutes was profoundly surprising. Indeed, it was a scientific revelation. The male continued counter-singing, trading nurrt calls with the neighboring male, but he then flew off his habitual perch and into the dark forest. In a few moments, however, I heard the long, thin, high-pitched, continuous, descending seeeeeeeeeeeee note approaching through the air. I then saw the male Golden-winged Manakin drop rapidly in flight to land on a large, exposed buttress root of a tree right in front of me. As he landed, he immediately rebounded into the air, turning around in mid-flight, vividly flashing his brilliant golden wing patches, and landed back down on the root facing back in the direction of his first landing position. As he landed, he froze in an elongate tail-pointing posture with his beak held down against the surface of the root, his body plumage sleek, and his tail held up at a forty-five- to sixty-degree angle in the air.

As rapidly as the brain converts an optical illusion from one image into an entirely new picture that was previously imperceptible, a rich and highly detailed set of scientific conclusions became immediately clear to me. The calls that were surprisingly similar to the White-throated Manakin’s were the log-approach display call of the Golden-winged Manakin. The host of remarkable similarities between the display behaviors of these two species were behavioral homologies—similar behaviors that they had both inherited from an ancient, shared ancestor, a common ancestor that no one had ever even conjectured might exist. Because the males of these two species look completely different from each other and are in two different genera, no one had ever before hypothesized that they were closely related to each other. However, after I saw their displays, it was immediately and vividly clear to me that the White-throated Manakin (Corapipo gutturalis) and the other Corapipo manakins were the closest relatives of the Golden-winged Manakin.

The log-approach display of the male Golden-winged Manakin.

It is hard to express how astounded I was by this discovery. It was a true epiphany, the culmination of weeks of futile searching, nine months of planning for the trip to the Andes, five months of previous fieldwork in Suriname, years of academic studies in ornithology and the sciences, and a parallel life of birding. All these influences had coalesced in an instant to reveal a heretofore entirely unsuspected connection. Never once during all my planning for this Andean expedition for the Golden-winged Manakin had I imagined such a possibility, that I could rewrite the phylogeny of the manakin family. Nor could I have, in my wildest dreams.

Of course, the stunning result of the expedition was personal proof that it really pays to listen carefully to the voice of one’s private ornithological muse. It pays to be lucky, too, for obviously I could never have come to this moment without my previous observations of the White-throated Manakin, which I was among the very few people on earth to have seen. My observations of White-throated Manakins in Suriname proved to be a unique and essential preparation for understanding the evolutionary implications of what I had witnessed in El Placer. What’s more, this newly revealed evolutionary pattern also implied something fundamental about the process of sexual selection by mate choice and the consequences for the assembly of complex repertoires of ornamental traits and seductive signals. Thirty years later, these discoveries still resonate in my work.

In the coming weeks, Ann and I would spend over 150 hours watching, tape-recording, and filming the display behaviors of the Golden-winged Manakin. It would take me much more analysis in order to establish the exact details of the host of behavioral homologies shared between these species since their common ancestor. It was obvious that long ago a common ancestral species had evolved a unique display repertoire, elements of which the Golden-winged and White-throated Manakins still exhibit in the present day.

But it was also clear that over time parts of that repertoire had diverged and transformed, with each species evolving its own unique display elements. I discovered many such differences between them. For example, once on the log, the Golden-winged males do not perform the bill-pointing posture and the to-and-fro display like those of the White-throated Manakin. Nor do Golden-wings perform anything like the wing-shiver display, even though they have a glorious golden wing patch to show off during such a display. Male Golden-winged Manakins do, however, have a unique display of their own. Once on the log, the male performs an elaborate “side-to-side bowing display,” in which he fluffs out his body plumage, cocks his tail slightly, and erects the tiny black hornlets on either side of his golden crown. Then, with the mechanical rhythm of a windup toy in a davening trance, he bows forward, nearly touching his bill to the log, rises up, takes a few steps to the side and rotates a bit, bows again, takes a few steps back in the original direction, and bows, and so on. The males we observed continued this display for ten to sixty seconds without interruption. Nothing remotely like this occurs among the White-throated Manakins or any other manakin species.

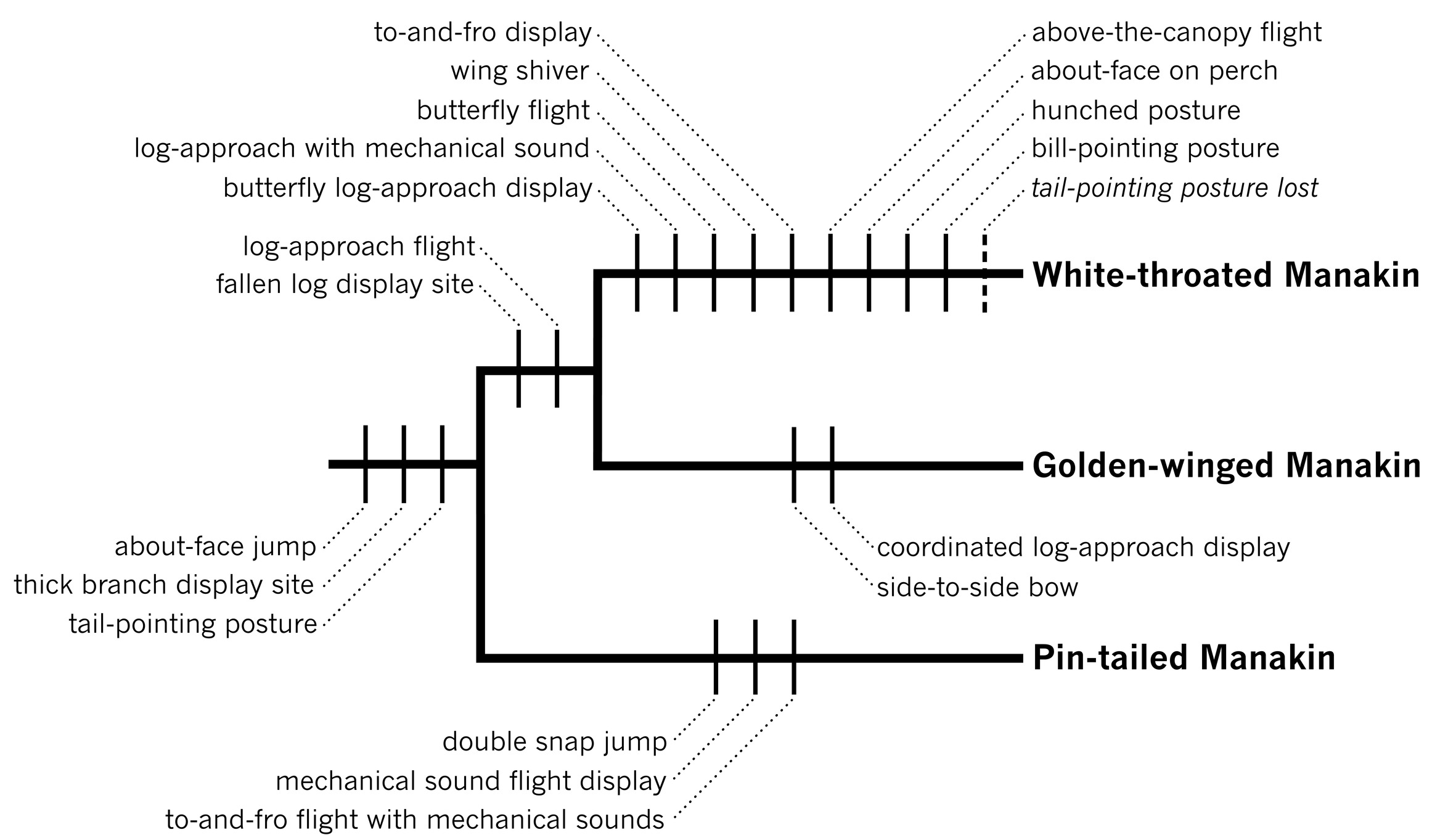

These exciting discoveries helped establish that the aesthetic repertoires of manakins are hierarchically complex. The visual, acoustic, and acrobatic displays of manakins are composed of some behavioral elements that have been handed down from their ancient common ancestors, and others that have subsequently evolved in unique ways in each of those species. The beauty of manakins cannot be understood solely in terms of the current environment or population context, but is contingent upon phylogenetic history. The full evolutionary history of beauty can only be understood in the context of phylogeny. The history of beauty is a tree.

Fleshing out the details of what behaviors had changed evolutionarily on what branching of the tree required my finding a third manakin species to which I could compare the Golden-winged and White-throated Manakins. In the same sense that it takes more than two data points to describe a statistical trend, it is difficult to make conclusions about the details of evolutionary history from a comparison of just two species. For example, spider monkeys have tails, but humans do not. Clearly, some evolution in tails has happened since these two species had a common ancestor, but which way did it go? Did the spider monkey evolve a tail? Or did the humans lose one? Only by looking at a third, more distantly related species—say, a lemur, tree shrew, or dog—can we infer that the evolutionary event was the loss of the tail in an ancestor of humans after shared ancestry with the spider monkey.

The tail-pointing (left) and side-to-side bow (right) displays of the male Golden-winged Manakin.

So, what third species could I use to reconstruct the evolutionary history of the Golden-winged and White-throated Manakins? It would have to be closely related enough to Golden-winged and White-throated Manakins to be useful. (In the example above, comparing primates with sea urchins, worms, or jellyfish would not have helped me infer the evolutionary history of their tails.) Luckily, in the fall of 1985, soon after my return from Ecuador, Barbara and David Snow published a beautiful description of the poorly known courtship display behavior of the Pin-tailed Manakin (Ilicura militaris) from the lower montane forests of southeastern Brazil. The male Pin-tailed Manakin has the bright, crisp, bold plumage color patterns of a toy soldier, as the scientific name of the species suggests (color plate 11). The male is gray below, black on the back and tail, green on the wings, with a red rump and a bright red plush fore crown. The central feathers of the male’s black tail are narrowly pointed and twice the length of the other tail feathers. The female is olive green above, and dull greenish-gray below, with somewhat elongate central tail feathers.

Because the male Pin-tailed Manakins look entirely different from the male Golden-winged and White-throated Manakins, these three species had never been hypothesized to be closely related. However, as I read the Snows’ descriptions of the display repertoire of the Pin-tailed Manakin, I could see that many of its elements resembled the behaviors of Golden-winged and White-throated Manakins, and I was certain that the Pin-tailed Manakin was closely related to the Golden-winged and White-throated Manakins. By including the Pin-tailed Manakin in my analysis, I was able to resolve many outstanding questions about the evolution of the behavioral repertoires of the Golden-winged and White-throated Manakins. By comparing all three species, I could identify which display behaviors had evolved in the common ancestor of all three species, which behavior novelties had evolved in the exclusive ancestor of the Golden-winged and White-throated Manakins, and which behavioral elements had evolved uniquely in each of the three species.

For example, I first considered the evolution of the male display sites. Most manakins display on thin tree branches. Golden-winged and White-throated Manakins are unique in the family in displaying on mossy fallen logs on the forest floor. Pin-tailed Manakins, on the other hand, display on upper surfaces of thick horizontal branches of trees, which are basically like living logs up in the trees. So, it appears that displaying on thick branches evolved in the common ancestor of all three species from the thin perches of ancestral manakins. Then displaying on fallen logs or buttress roots evolved subsequently in the exclusive common ancestor of the Golden-winged and White-throated Manakins.

Another trait I examined was the tail-pointing posture. On their thick display branches, Pin-tailed Manakins perform a tail-pointing posture that is homologous with the Golden-winged Manakin’s but doesn’t resemble anything the White-throated male does. Thus, I concluded that the tail-pointing posture had evolved in the common ancestor of all three species but was lost in the White-throated Manakin lineage and replaced by the novel bill-pointing posture.

The tail-pointing display of the male Pin-tailed Manakin.

By thoroughly comparing the behaviors of all three species, I developed a comprehensive hypothesis of the history of behavioral diversification in the group. The display repertoires of each species had included physical, vocal, and display elements and had evolved in many creative ways: by insertion of entirely novel elements into the repertoire; by the elaboration of current elements in new ways; and by the combinations of elements and the loss of ancestral elements. I was able to propose an entirely new hierarchical view of the coevolutionary history of manakin beauty.

For my doctoral dissertation, I went a step further, using new information about manakin anatomy to produce a reasonably complete and well-resolved phylogeny of the entire manakin family. This research involved hundreds of dissections of the syrinx—the unique little gizmo the birds sing with—of all manakin species. I then used this evolutionary tree to test my hypotheses about behavioral homology. For example, I found common features of syringeal structure that confirmed my hypothesis that the Pin-tailed, Golden-winged, and White-throated Manakin genera had an exclusive common ancestor. And, as I had proposed based on their display behavior, these features also pointed to the Golden-winged and White-throated Manakins’ being more closely related to each other than either was to the Pin-tailed Manakin.

Phylogeny of the White-throated, Golden-winged, and Pin-tailed Manakins depicting the evolutionary origins and losses of the behavioral elements within the display repertoires of each species and their shared ancestors. Based on Prum (1997).

Today, what we know of the aesthetic radiation of manakins provides many evolutionary lessons about how Beauty Happens over the Tree of Life. We’ve learned that manakin aesthetic repertoires include many elements that are older than the individual species themselves. We can see that each species’ display repertoire is contingent upon both the evolutionary legacy of that species—what it inherited from its various ancestors—and any new display elements—aesthetic elaborations, innovations, or losses—that have evolved in that species alone.

How the elements of a given display repertoire come into being over the course of time shows us the inherently serendipitous and unpredictable nature of aesthetic evolutionary process. From a common history, sister species evolve in many different and unpredictable aesthetic directions. Through each aesthetic change, mate choice also creates new aesthetic opportunities, which can unleash an evolutionary cascade of effects. These include the evolution of further aesthetic extremity and complexity. As Beauty Happens, different species evolve off in ever more different, arbitrary directions from their shared ancestral repertoires. Especially when sexual selection is strong, as in manakins and other lekking birds, Beauty Happening over the course of long evolutionary timescales results in explosive aesthetic radiations.

My fieldwork in Suriname in 1982 launched me on a path of exploration that I have continued to follow down to the present day (though with diminished capacity in recent decades due to major hearing loss). In the intervening decades, I have conducted ornithological research in twelve neotropical countries and have had the good fortune to observe nearly forty species of manakins in the wild. (I am still working eagerly to see the rest.) For some of those species, I spent hours, days, or even months of observation getting to know their habits, observing their daily rhythms, describing their courtship songs and dances, and mapping out their social relationships. This helped me to build a rich database of natural history knowledge about manakin behavioral complexity and aesthetic diversity.

But my ever-expanding knowledge of manakin diversity also taught me to ask bigger, more fundamental questions about the evolutionary workings of the natural world. Early on, I had thought of manakins as colorful birds with delightfully bizarre display and social behaviors. Later, I conceptualized the manakins as a great example of how the complex mechanisms of mate choice affect behavioral evolution among species. Most recently, I have come to think of manakins as one of the world’s premier examples of aesthetic radiation. And as we’ll see in a later discussion of manakins (see chapter 7), the female manakins haven’t only transformed male display repertoires; they’ve changed the very nature of male social relations. It’s an astonishing story of the transformative power of female mate choice.

Manakins are just one small piece of a vast tapestry of avian beauty. There are over ten thousand species of birds in the world, ranging from the plainest of sparrows to the most exquisite of manakins. Because every single bird species exhibits some specific sexual ornaments that are employed in courtship communication and mate choice, it is clear that the capacity for mate choice in birds originated in an ancestor common to all birds, perhaps even in a lineage of feathered theropod dinosaurs dating all the way back to the Jurassic. From this single common ancestor, the repertoire of aesthetic traits and mating preferences has continued to coevolve and radiate into the many thousands of distinct forms of avian beauty that exist today. On different phylogenetic branches at different times, the pace of coevolutionary change has slowed or increased as new ecologies have contributed to variations in breeding systems and parental care arrangements, which in turn have given rise to tremendous variation in the nature and strength of sexual selection by mate choice. Along the way, mate preferences have continued to evolve in various avian lineages, sometimes occurring in both sexes, sometimes in females only, or, much less often, in males only, and the aesthetic repertoires of the sexes have coevolved accordingly. Each lineage and species has evolved along its own distinctive and unpredictable aesthetic trajectory. The result has been the flowering of more than ten thousand distinctive aesthetic worlds comprising over ten thousand coevolved repertoires of displays and desires.

Something comparable has occurred on myriad different branches across the entire Tree of Life. From poison dart frogs and chameleons to peacock spiders and balloon flies, whenever the social opportunity and sensory/cognitive capacity for mate choice has arisen, an aesthetic evolutionary process has taken hold. This aesthetic evolutionary process has arisen hundreds or thousands of times during the history of life, even in plants that have evolved ornamental flowers of distinct shapes, sizes, colors, and fragrances to seduce animal pollinators into dispersing their gametes (in the form of pollen) to other flowers waiting to be fertilized.

Throughout the living world whenever the opportunity has arisen, the subjective experiences and cognitive choices of animals have aesthetically shaped the evolution of biodiversity. The history of beauty in nature is a vast and never-ending story.