Come out to Taliesin West sometime this winter—bring a friend—why not Philip?—for a friendly wrangle over consequences.

—Frank Lloyd Wright

A glass box may be of our time, but it has no history.

—Philip Johnson

1958 … New York City … Closing Conversations

Before he died, Wright had experienced intimations of his mortality. In the autumn of 1957, he frightened everyone around him at Taliesin when he took a tumble. Wright read the fall as a warning. A spirit like the one that had permitted him to soften his style with Aline Saarinen left him thinking aloud about his legacy.

In February 1958, Wright, long a rider of trains, chose to fly to New York from his winter quarters in Arizona. On the way to check construction progress at the Guggenheim Museum, he had arrived at New York International Airport, the site of Eero Saarinen’s new TWA terminal, a building that, like the Guggenheim, featured organic curves. Soon that structure would be likened by critics to bird wings and clamshells.1

The clerk-of-the-works at the Guggenheim, New York architect William Short, picked him up at the airport. Speaking of the spill he had taken, Wright told Short, “I thought that was the end and I am chastened. It made me think that enmity is a very petty thing and I do not want to die with any enemies, so I am going to call up Philly Johnson, [Guggenheim director] Sweeney, Miës and Henry-Russell Hitchcock and have them all in for dinner.”2

Wright had indeed called Philip Johnson and Hitchcock: “Philip, I am getting too old to have any more of these fights and have enemies, I can’t stand it, let’s have dinner together.” When they met—Hitchcock, due to a bout of the grippe, was unable to attend—Johnson found Wright “mellowed,” less his usual “temperamental and peppery self.”3

At the time of their dinner, Johnson was filling in at Yale for Professor Vincent Scully, off on sabbatical. Co-teaching a survey course with Hitchcock and John McAndrew, Johnson focused on his allotted portion of the syllabus, twentieth-century architecture.4 He talked of Miës and Le Corbusier, but one May evening he wandered off his prepared text. He mused aloud with the students about his meal and conversation with Frank Lloyd Wright, which had transpired a few days before.

“My unfortunate remark about his being the greatest architect of the nineteenth century,” Johnson began, “is like all such silly statements full of inaccuracy.”

Johnson flashed slides of the Robie House and the Johnson Wax tower. When the model of the St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bouwerie Towers appeared on the screen, he expressed surprise. “I used to dislike this building extremely … because it’s so against anything that I would do. But who is right here, you see? It’s just fairly possible that Mr. Wright is further ahead than any of us. It’s perfectly possible that this building may represent the relief from the blandness of the past twenty years.”5

Having spent decades jabbing Wright with his sharp elbows while defending the austerity of Modernism, Johnson offered the man—in absentia—a pat on the back.

A few months later, shortly before his death, Wright called Johnson again from his suite at the Plaza. Johnson remembered the conversation this way:

“He called me one day without announcing who he was; the voice sounded familiar. He said, ‘Who’s this, do you think?’”

“If I didn’t know better,” Johnson remembers replying, “I’d say it was Frank Lloyd Wright.”

Wright again extended a dinner invitation, and Johnson agreed.

“We had a stroll,” Johnson recalled. “I brought Phyllis Lambert along. I thought it was good for her education. Most charming man in the world.”

Perhaps Wright was making amends, but Johnson couldn’t be sure. “I think … that’s why he called me that night. I think he wanted company … He didn’t like me particularly, but I stirred him up, anyhow. So he just called.”6

That would be their last conversation.

“We’d made all the battles we were going to have,” Johnson remembered.7 That said, Philip Johnson, age fifty-two, would find he still had to wrestle with Wright’s cantankerous spirit for more than four decades.

The Glass House … The Diary of an Eccentric Architect

Frank Lloyd Wright’s death aligned with a change in Philip Johnson’s practice. Commissions had been running roughly four to one in favor of domestic clients, but after 1959, the balance shifted with the arrival of more university, museum, theater, library, and other public work.8

Johnson’s designs changed, too. “I have always been delighted to be called Miës van der Johnson,” he announced at Yale a few weeks before Wright died. “It has always seemed proper in the history of architecture for a young man to understand, even to imitate, the great genius of an older generation.” But, Johnson announced, he was ready to move on. “I grow old. And bored.”

He offered one hint concerning his new orientation: “I try to pick up what I like throughout history.” Then he added another clue, a phrase that would echo through the years: “We cannot not know history.”9

At the time, his words sounded cryptic, but Johnson was distancing himself from strict Modernism. His new and evolving mode (he called it “eclectic traditionalism”) was in part a reaction against rigorous functionalism. He was working his way backward, as he told a lecture-hall audience at the Metropolitan Museum in 1961. “We find ourselves now all wrapped up in reminiscence … It’s a stimulating and new feeling of freedom … We have no wish to revolt against the past; … we can be freer.”10

Three years after Wright’s death, Philip Johnson would add a new and largely decorative structure at his Glass House property. He called it a folly, alluding to the landscape gardens of Enlightenment England with their collections of little teahouses, faux ruins, and classical temples. The little temple he built on his Ponus Ridge Road property would be one of the first blooms in what would be the second flowering of his architectural career. Like Wright’s Taliesins, Johnson’s New Canaan acreage would become—as he himself put it—“a clearinghouse of ideas which can filter down later, through my work or that of others.”11

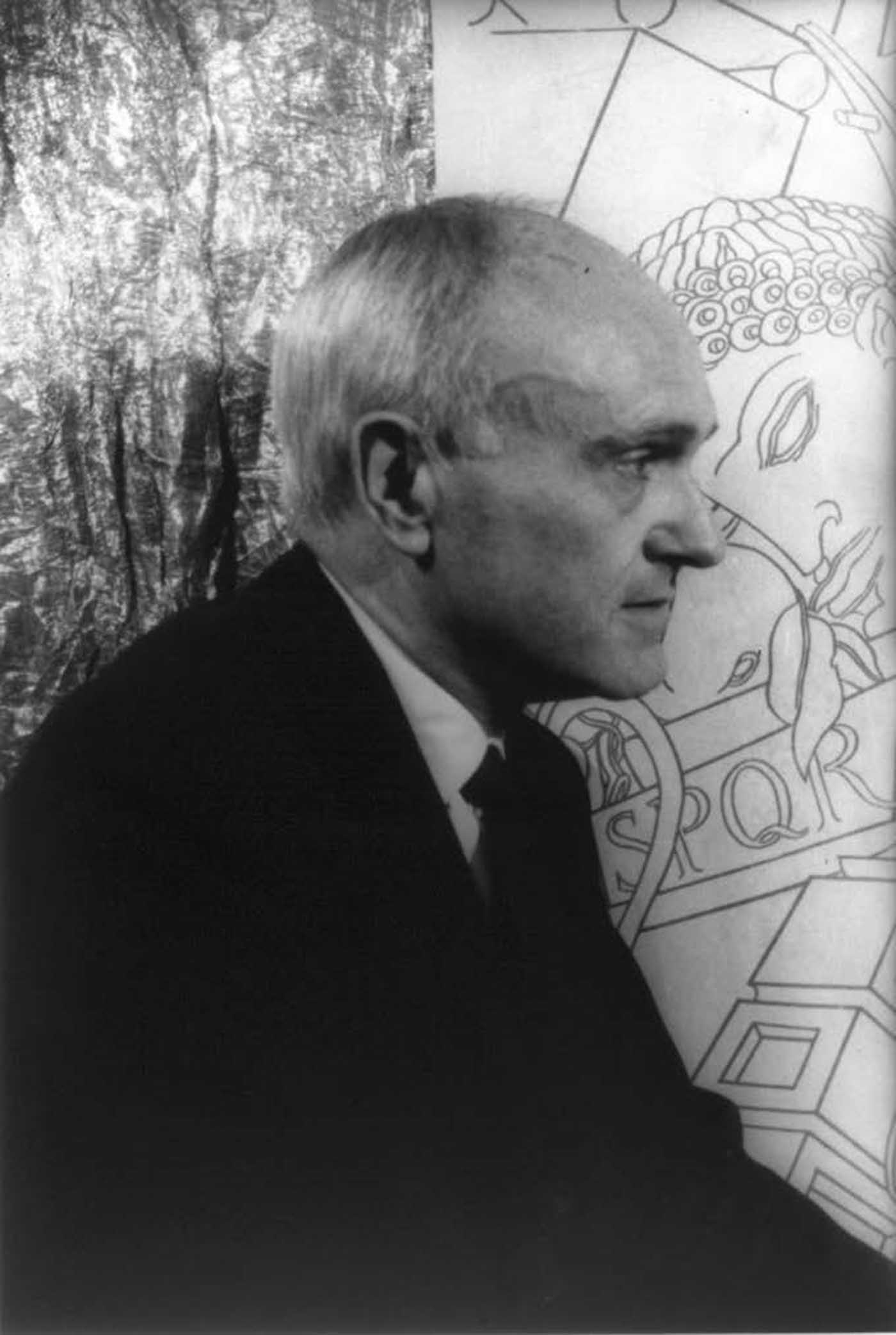

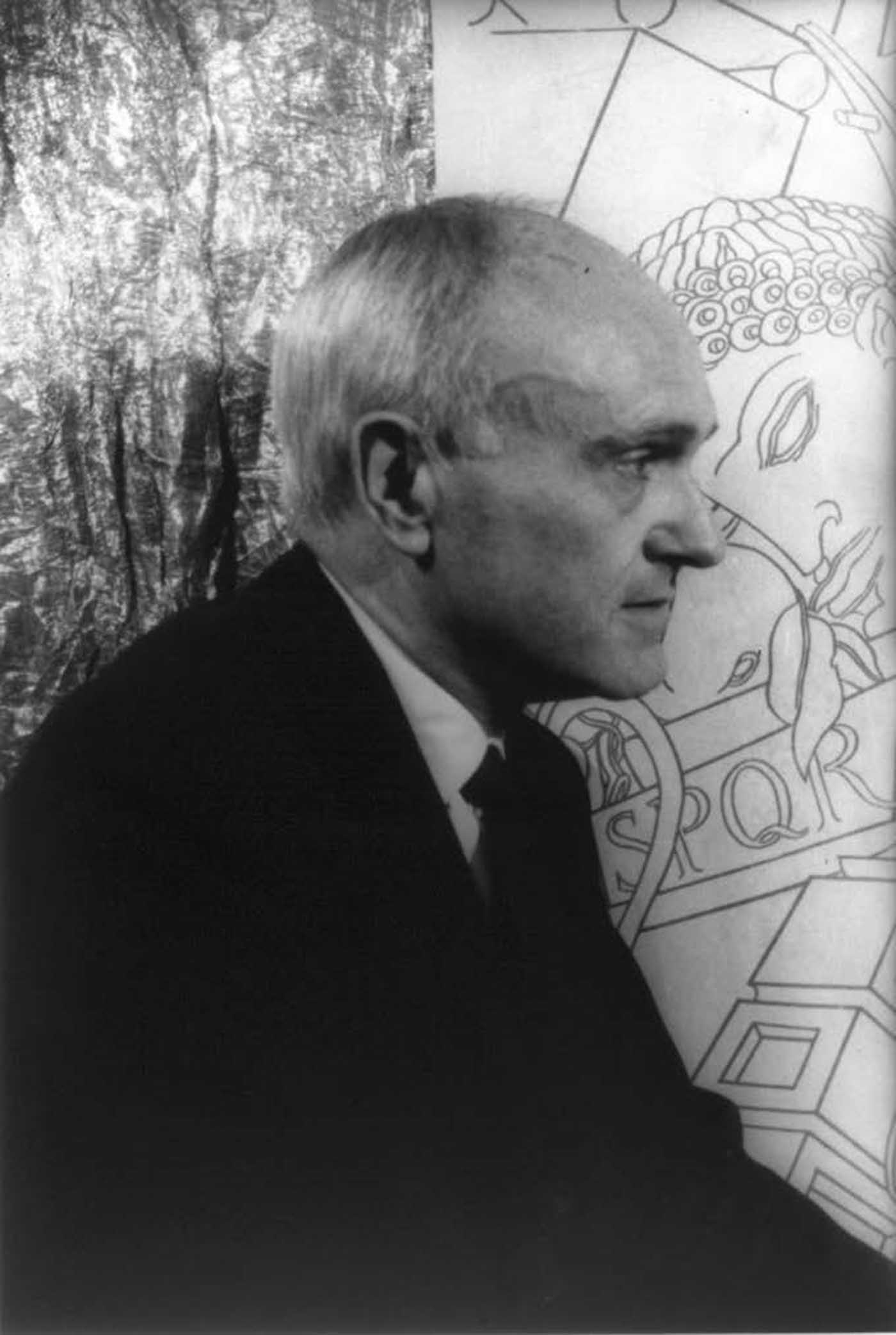

Philip Johnson, ca. 1963. (Carl Van Vechten, Library of Congress/Prints and Photographs)

––––––

Recalling that his mother once did the same thing in Ohio, Johnson dammed the little stream that meandered through his New Canaan property. A fountain plumbed beneath the new man-made pond shot a narrow jet of water more than a hundred feet into the air. Just out of reach of the spray that fell back to earth, Johnson installed his garden temple of precast concrete.

He called it his Pavilion. Built on a plan Johnson likened to a Mondrian grid, the little structure was flat roofed, its walls consisting of open arcades. The flattened arch occupied his professional attention at the time, as he experimented with façade designs for the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, and the Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery (1963), in Lincoln, Nebraska.

Yet the picnic Pavilion wasn’t quite what it seemed. The little belvedere was, in fact, an exercise in trompe l’oeil. Built just under human scale, its size gave it the appearance of being farther from the Glass House than it actually was. The oddity of its proportions became abundantly clear on approach, since guests six foot and over had to stoop to enter.

“My pavilion is full scale false scale,” Johnson explained to readers of Show magazine, “big enough to sit in, to have tea in, but really ‘right’ only for four-foot-high people.”12 The New Canaan temple, which appeared to be sitting upon the water, represented a venture into the classical past, a hint of immensely larger experiments in Johnson’s historicist future.

Johnson’s picnic place, built in what he called “full scale false scale.” The pavilion is bigger than a dollhouse, but with arches that are just under six feet tall, Johnson had to duck his head to enter. The folly is very much in the viewscape of the Glass House, seen here at the horizon line. (Carol Highsmith, Library of Congress/Prints and Photographs)

With the appearance of David Whitney, Johnson’s personal life also changed in a significant way. A student at the Rhode Island School of Design, Whitney attended a Johnson lecture, in 1960, at nearby Brown University. He approached Johnson afterward, asking for a tour of the Glass House; his arrival the following weekend in New Canaan precipitated their long relationship. Despite being thirty-three years younger, Whitney helped Johnson to a new constancy in his private affairs, and they remained a couple at Johnson’s death more than four decades later. In the interim, as a sometime MoMA curator and, later, a gallery operator, Whitney also disciplined Johnson’s art collecting. “David is my contemporary art,” Johnson once told the New York Times. “I don’t have an original eye.”13

A rapid growth in Johnson’s art holdings was soon reflected in the construction of two more buildings on his property in New Canaan. The Painting Gallery came first, in 1965, a building with a cloverleaf plan, a showcase almost as unexpected as Wright’s Guggenheim. Each of its four “leaves” featured a central post around which movable gallery walls pivoted like spokes on a wheel, displaying works by Jasper Johns, Frank Stella, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, and other contemporary artists. Dug into the slope just north of the Glass House, the gallery was buried beneath a mound of earth like a Neolithic barrow. Later the Sculpture Gallery, built in 1970, enclosed a central court—really an outsize brick stairway that descended five levels from grade—beneath a glass-and-steel roof that cast linear shadows on the sculpture displayed. In Johnson’s public life, too, he was very much an art-gallery man in these years; in addition to the Amon Carter and Sheldon museums, he designed the elegant set of nine glass cylinders for the Museum of Pre-Columbian Art at Dumbarton Oaks (1963), in Washington, D.C., as well as the MoMA’s East Wing (1964).

In 1980 Johnson built himself a freestanding studio and library in New Canaan. “A monk’s cell by intent,” Johnson said, it was an experiment in pure geometry, a conjoined cube and cylinder capped by a truncated cone that resembles a chimney but houses a skylight. In 1984 a kennel-like construction of chain-link fencing in the shape of a simple gable-roof house was constructed. Called the Ghost House, this homage to Johnson’s friend Frank Gehry was built atop an old barn foundation.

Numerous other buildings were added to the property over the years. The last of them, which Johnson called Da Monsta, was intended to accommodate visitors after Johnson’s death. Looking to secure his legacy, Johnson conveyed the New Canaan property to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, whose roster of sites already included Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home and Studio in Oak Park, Illinois. The undulating lines of the visitor center reflected a late reprise of Johnson’s MoMA connection, namely the 1988 exhibition Deconstructivist Architecture. As co-curator, Johnson arranged for the participation of such notable end-of-the-century architects as Gehry, Peter Eisenman, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, Daniel Libeskind, and Bernard Tschumi. When Johnson designed Da Monsta, he incorporated echoes—whether consciously or not—of the sinuous surfaces, unlikely fenestration, and obscured entrance of Wright’s Guggenheim. That building had become an undeniable presence in the mental slide tray of every museum architect.

Johnson’s Painting Gallery has been said to be a descendant of another late Wright design, but Wright’s influence on Johnson’s relationship with his landscape is more apparent.14 In creating the Pavilion and the dozen-odd other follies, Johnson extended his reach into his setting. As his holdings increased over the years (eventually, he would own almost fifty acres), so did his deep debt to the Taliesins. As his sometime Yale colleague Vincent Scully would observe, “His place now joins … Taliesin … as a major memorial to the complicated love affair Americans have with their land.”15

Wright had revealed to Johnson how integral landscape is to architecture. That knowledge informed Johnson’s siting of his buildings in the context of rural Connecticut’s stone walls, rolling and sloping terrain, and trees (“Trees are the basic building blocks of the place,” offered Johnson).16 Johnson incorporated water, just as he had done earlier in designing the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden at the MoMA (1953), where he employed trees and “canals,” as he called them, to interrupt museumgoers’ progress, explaining the effect he wanted was “always the sense of turning to see something.” He linked his inspiration to Wright: “By cutting down space, you create space. Frank Lloyd Wright understood that, but Miës didn’t. Miës would probably have designed it symmetrically.”17

Their objectives for their homes differed. Wright ran a school, and the unique campuses he created in Wisconsin and Arizona doubled as architectural laboratories. Johnson’s New Canaan property was more personal; in his own words, it amounted to the “diary of an eccentric architect.”18 To visit the Glass House estate was to walk the backbone of Johnson’s architectural career, starting with its most essential datum, the Glass House itself. The house hadn’t leapt out of his forehead all in a moment—recall his trial run at 9 Ash Street and his debt to Miës—but it represented the unexpected emergence of the understudy as a star.

For both Wright and Johnson, their homes became their testing grounds, places where they built structures that encompassed many of the themes of their architectural careers. Two of the most eccentric structures—one at Spring Green, the other at New Canaan—contrast with undeniable clarity the workings of the two men’s architectural imaginations.

Early in his career (then, in 1896–97, Wright actually was a nineteenth-century architect), he built the Romeo and Juliet Windmill (see Fig. XXIII). Aunts Nell and Jane Lloyd Jones needed a reliable supply of water for their school, and a commonplace windmill of steel trusses purchased out of an agricultural catalog would have done the job of pumping it from a deep artesian well to the hilltop reservoir. But nephew Frank chose to make a statement in designing a fifty-six-foot-tall tower with a fourteen-foot wheel.

He designed the structure on an octagonal footprint, but one into which a diamond had been driven like a dagger. The diamond-shaped prow that resulted pointed southwest, into the prevailing winds, slicing through them to diminish their force on the tall building. Covered with board-and-batten siding, the wooden superstructure was stiffened and secured to its base of stone with iron rods. It gained its name from the manner in which the octagon embraces (and is penetrated by) the diamond. Situated on a Taliesin hilltop, the Romeo and Juliet Windmill surveys the Wright demesne.

In contrast, Johnson’s Kirstein Tower, constructed in 1985, had no utilitarian purpose; it’s very much an eye-catcher in the spirit of the eighteenth-century landscape garden. Built of concrete block, it’s named for Johnson’s enduring friend and confidant Lincoln Kirstein, a poet and cofounder of the New York City Ballet, for whom Johnson built the New York State Theater (1964) in Manhattan’s Lincoln Center. An orderly and immense stack of eighteen-inch-square blocks, the Kirstein Tower in New Canaan looks like an idle doodle on a notepad come to life—but on examination, its pure geometry resolves into a stair rising to nowhere. It is monumental and cantilevered, with intimidating tall treads and no rail.

Set into the hillside overlooking the pond and the temple, it is, according to Johnson, “a study in staircases.” Perhaps it references Kirstein’s preoccupation with dance. It’s rectilinear, but the “treads” encircle (and are) the structure. It’s ambiguous—“I suppose it’s architecture,” commented Johnson, “or is it sculpture?”19

The Kirstein Tower and the Romeo and Juliet Windmill reflect their creators’ differing inspirations. Wright built something elemental, at once decorative yet inseparable from the earth, wind, and water. Johnson employed wit and whimsy. Both produced biographical vignettes.

New York City … Skyscraper Days

In 1979, Time magazine made the arrival of Post-Modernism official. The style’s papal presence, Philip Johnson, adorned the cover of the January 8 issue. He held a three-foot-tall model of his new project, the AT&T Building (now the Sony Plaza), as if it were one of Moses’s tablets. With his coat draped over his shoulders like a cape, Johnson was eerily reminiscent of the man whose influence he so often disowned but grudgingly loved.

The AT&T Building came to be called the Chippendale Skyscraper because its form resembled that of high-style, eighteenth-century case furniture. Though the building on Madison Avenue was not completed until 1984, the publicity surrounding it anticipated an embrace of architectural history by the American corporation, partly in reaction to stripped-down, steel-and-glass Modernism, which, after the Seagram Building, has become the de facto urban style. It contained echoes of the brilliant Louis Sullivan, Wright’s long-dead mentor. Almost a century later, Sullivan’s 1896 essay “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered” was rediscovered by a generation bored with glass boxes. Johnson and others adopted his notion of the skyscraper as consisting of three parts: in effect, a plinth of several stories at the base; a shaft (“tiers of typical offices”); and a capital (Sullivan called it an “attic”) that offered the building’s “conclusiveness of outward expression.”20

In partnership with John Burgee (“I’ve always had a John Burgee,” Johnson would explain, “to keep things on the straight and narrow”), Johnson exercised his gift for salesmanship as well as his eclecticism (“I had the ideas and the flair”).21 He demonstrated a penchant for geometric experimentation in Minneapolis with the faceted-glass atrium of the IDS Center (1973); in Houston with Pennzoil Place (1976), which consisted of twin, trapezoidal-topped towers; and, later, with the elliptical “Lipstick Building” (1986) at 885 Third Avenue in New York. His historicist experiments extended to Gothic pinnacles for PPG Place (1984) in Pittsburgh; an Empire State Building wannabe (the Transco Tower in Houston, 1983); and a nearly straight lift of an unbuilt ca. 1800 school design by French neoclassicist Claude Nicolas Ledoux, which became the University of Houston Architecture Building (1985). As a young man, Johnson had established himself as an architectural historian; as an aging one, he explored his intellectual attic, employing ideas from what Scully admiringly termed Johnson’s “stored mind.”22

Johnson won the first-ever Pritzker Architecture Prize, in 1979, an instantly prestigious honor given only to living architects. From his corner table in the Grill Room at the Four Seasons, he moderated an ongoing seminar and power chat devoted to American architecture. He dined with fellow Post-Modernists, two of whom, Michael Graves and Robert A. M. Stern, he credited with helping brainstorm his highboy tower for AT&T. Johnson would also welcome to his table the Deconstructivists and numerous others who benefited from his patronage. By the time Johnson’s first full-scale biography appeared in 1994, written by Franz Schulze (who had written an admiring and admired life of Miës van der Rohe), the New York Times (in the person of architecture critic Paul Goldberger) could fairly term Johnson “the greatest architectural presence of our time.” Often referred to as the “Dean of American Architecture,” Johnson had become the most celebrated American architect of his generation. His name amounted to a designer label for big-ticket projects; his face had become well-known to television audiences and appeared on the covers of glossy magazines.

Johnson continued to build museum, ecclesiastical, and domestic structures, but in a way that Wright could never have done, he designed the skins for corporate towers, commissions that typically arrived with predetermined volumes that he was permitted to decorate (among them the Transco Tower in Houston and International Place in Boston). A proud citizen of the city, Johnson adapted his works to their urban environs. He merged his buildings with the pattern of the places—unlike Wright, who, denying the weft and warp of a rectilinear place, had spun spiral in his only two permanent New York structures. Johnson’s buildings were diverse, dispersed around the country and the world, and were rarely executed in anything resembling a Wright vernacular.

Yet Wright remained a presence in Johnson’s thinking. “I’m not a form giver,” Johnson told Vanity Fair in 1993. “I’m no Miës. I’m not Wright. I wish I were.”23

The Form Giver and the Aesthete

In life, Wright enjoyed tweaking Philip Johnson, but over the years, his manner had softened.

Both Wright and Johnson pushed boundaries, and their designs were known to test (and sometimes exceed) the technological limits of their times. Late in the evening of their memorable 1955 encounter at Yale (“Philip! I thought you were dead!”), Wright had also remarked to Johnson’s face, “Little Phil, all grown up, an architect, and actually building his houses out in the rain.” In an unexpected way, the latter remark can be seen as almost comradely.

Its origin, twenty-five years before, was an observation made by Mrs. Richard Lloyd Jones. Her husband, a cousin of Wright’s, had commissioned him to build a house during Wright’s quietest years. When a prospective client, Herbert “Hib” Johnson, came to scout Westhope (1929) in Tulsa, Oklahoma, he arrived in a driving rain. On entering the home, he saw a number of strategically placed containers, each located to catch the copious drips that fell from the leaky roof. Seeing Johnson’s quizzical look, Mrs. Lloyd Jones explained, “This is what happens when you leave a work of art out in the rain.”

To Wright’s good fortune, however, Hib Johnson had been undeterred (he would commission Wright to design him a home and the landmark Johnson Wax Administration Building with its unforgettable mushroom columns and the memorable Pyrex-tubing roof, which also leaked volumes of water). Wright’s reuse of the out-in-the-rain drollery to apply to Johnson’s Glass House could well have been a backhanded, welcome-to-the-club commentary, one catty architect to another.

The old master, whom Johnson had dismissed in early manhood, gradually became a touchstone as Johnson himself aged. In 1975, he gave a lecture he titled “What Makes Me Tick.” He told the assembled students at Columbia University, “In modern times, at Taliesin West, Frank Lloyd Wright made the most intriguingly complex series of turns, twists, low tunnels, surprise views, framed landscapes, that human imagination could achieve.”24 In critiquing one of his own buildings, in 1985, Johnson found the Bobst Library at New York University (1973) “strangely unsatisfactory,” since, Johnson explained, “the third dimension—I mean Frank Lloyd Wright’s great passion—was lacking.”25 In 1977 he told Calvin Tomkins of the New Yorker, “We didn’t know how good Wright was then.”26

Later still—by then he was well into his eighties—Johnson told an interviewer, “There isn’t a day that doesn’t go by without my thinking of Mr. Wright; there isn’t a day that I don’t feel—when I have a pencil in my hand anyhow—that the man isn’t looking over my shoulder.”27

Over the years, it became second nature for Johnson to call Wright “the greatest architect of our time.” Once, when asked to explain his change of heart, Johnson didn’t hesitate: “No, I don’t have any ambivalence. I was wrong about Wright in the thirties.” Johnson added, “Don’t forget I knew him before his great masterpieces were built—Fallingwater and Johnson Wax. Those two buildings alone could put an architect at the head of the century.”28

Johnson’s recollections softened personally as well as professionally. “Wright was a very protean type. I mean he was in the middle of writing these awful letters [their ca. 1932 MoMA correspondence], and we’d get together and joke … Wright was a very genial, loving man—very forgiving. I mean I wouldn’t have forgiven that little snot Philip Johnson. Why would he? Because I was always, as you know, indiscreet and yappy. He was a very great man.”29

In a way, the Wright connection was, for Johnson, lifelong: Louise Johnson had talked about hiring Wright to build her house before she became a mother. That isn’t to say that her son didn’t work to resist Wright’s influence; as he recalled in a 1994 interview, he had thought of Wright when he sited the Glass House: “[Wright] said never, never build on top of a hill. I chose the site because of the famous Japanese idea: Always put your house on a shelf, because the good spirits will be caught by the hill that’s behind the house; the evil spirits will be unable to climb the hill below the house.”30 But he didn’t mind when Wright complimented him. “I remember his telling me that’s the only thing he liked about my house, that I had sense enough to build it on a shelf … The shelf idea? I think I might have got it from Wright.”31 They did have their commonalities, and Johnson felt them. “Nature to Frank Lloyd Wright was fields, wetlands, and wild bushes … And my house is a house in the field … I was brought up in the same kind of culture he was.”32

Johnson made a similar admission to Robert A. M. Stern. When Johnson launched himself as an architect in the forties, he later told Stern, “I was still a total believer in the modern movement … But I also had a tinge of this other Wrightian, hovering-house feeling.”33 Yet in interviews, questions about Wright often made Johnson cranky, too, as if Wright were a family member. With blood relatives, you can’t very well disown them—but that doesn’t mean you can’t both love and deride them.

––––––

Did Johnson influence Wright? Wright was nothing if not adaptable. Just a few years after the 1932 MoMA exhibition, he had clearly taken aboard the European experiments he had earlier rejected and designed what many regard as the most memorable house ever constructed in the International Style. Very much later, Johnson put it succinctly: “Wright really built the Edgar Kaufmann house, Fallingwater, as an answer to our 1932 show at the museum—as though he were saying, ‘All right, if you want a flat roof, I’ll show you how to really build a flat roof.’” Wright rejected the suggestion the Kaufmann house was Internationalist, but Johnson, like a proud uncle, just smiled, observing, “It was a wonderful answer.”34 In the same vein, the Guggenheim is surely closer to the spirit of Modernism than to Wright’s pre-1932 work.

Two decades after Wright’s death, Johnson recalled Wright’s periodic visits to the Glass House. Johnson was half-annoyed that “Wright joked about my house” and half-admiring that the eightysomething Mr. Wright kept coming back. “His eyes stayed open.”35

By the time Philip Johnson died, in a hospital bed installed in the Glass House, in January 2005, it was clear that he and Wright had shared a rare gift: Both possessed the capacity for personal reinvention—and both exercised it over their long lives. The great works of Wright’s early, middle, and late life could easily have come from the drafting tables of three different men. The young Johnson was an idealistic curator; he became in midlife an architect in the Modernist vanguard; in his closing decades, he was an architectural polygamist who dallied with Post-Modernism and Deconstructivism but, through it all, never severed his ties to classicism.

Johnson has been called an ironist—he was happy to describe his glass-walled house as “my place to hide.”36 He called himself a pasticheur. Termed by various critics an impostor and a joker, Johnson was capable of shocking cynicism in his own defense. He told a roomful of internationally recognized architects, in 1983, “I do not believe in principles, in case you haven’t noticed.” Then he added, “I am a whore, but I am paid very well for building high-rise buildings.”37

The word that his authorized biographer, Franz Schulze, chose to describe his elusive subject was Harlequin, the stock theatrical character that emerged from commedia dell’arte. Johnson was indeed a nimble trickster, characterized by his sly, mischievous, and changeable nature.

In contrast, the character of Wright’s work was notably constant. Certainly his forms varied. His architectonic preoccupations ranged from great sweeping Robie roofs to the cyclone on Fifth Avenue, from rectilinear to hemicycle, from Gilded Age mansion to Depression Era Usonian. Yet his organic creed was more than a rhetorical claim, and his adherence to organic principles remained fixed throughout his career. In 1896, he stated, “I have a mind to control the shaping of artificial things and to learn from Nature her simple truths of form, function, and grace of line.”38 By remaining faithful to the deceptively simple, though open-ended, principle of organic unity, he permitted his imagination to range freely. Paradoxically, that unity came to represent a creative freedom to explore diverse forms.39

Johnson never pretended to possess any gift whatever as a draftsman, but always had capable men at hand, starting with Landis Gores. Wright was an artist in the traditional sense, a master of the line who proudly recalled his role as head draftsman at Adler and Sullivan. He, too, hired talented draftsmen in his offices, ranging from Marion Mahony in the Oak Park days, who executed many of the most memorable drawings that emerged from Wright’s studio on Chicago Avenue, to John “Jack” Howe, head draftsmen at Taliesin for more than twenty-five years. But it was more than a matter of good drawing for Wright. As Lewis Mumford wrote a few months after Wright’s death, “The finished presentation drawings of his buildings are works of art in their own right … The drawings show—sometimes more clearly than even the actual buildings—the combination of formal discipline and effulgent feeling … the union of the mechanical … and the highly individualized arts, that were the man himself.”40

Johnson’s corporate clients understood they were getting a name-brand architect but one whose engagement would rapidly fade once the essential shape was agreed upon and the parti developed. Wright hungered for control all the way. Johnson never claimed an enduring philosophical underpinning; for Wright the philosophical almost rivaled the architectural.

If Wright found in his organic unity a means by which to explore diverse forms, Johnson’s unbridled approach was to pursue architecture for its own sake. He was an aesthete, not an artist; it is revealing that the Glass House, for which he is best known is, at least among architecture professionals, admired as much for the treatise he published in 1950 about it as for the building itself; it anticipated such next-generation architect-theorists as Robert Venturi, Rem Koolhaas, and Peter Eisenman, each of whom would routinely issue theoretical texts they wished to have attached to their designs.

Johnson began as a student of the classical past; for him, as a student of art committed to beauty first, architecture was all about style. He built one great house—his own, of glass—and contributed to one great urban building, a monument to whiskey. With the able assistance of men like Burgee, he made other intriguing buildings and influenced the corporate culture of his time and the look of the new city. He would remain true to his 1954 statement that “the aim of architecture is the creation of beautiful spaces.”41

Wright’s aspiration differed. He harbored loftier ideals, invoking democracy, truth, and the common man. He found his inspiration in Nature; he regularly disclaimed the influence of any and all other architects. He claimed to be original—as Johnson would widely be quoted as describing him, “the type of genius that comes along only every three or four hundred years.”

Johnson was content to mirror the work of the others, explore and expand upon tradition. While Johnson was a great looker, Wright was a seeker. Wright sought truth, while Johnson looked for something that pleased him. To tour a typical Johnson house is to engage a fine mind and sensibility at work; to explore a Wright house is to have an architectural experience.

One way to think about Johnson and Wright is to personify their signature buildings, to read Fallingwater and the Glass House as the men themselves.42 Fallingwater reaches out: It isn’t a bridge that straddles a stream; like the palm of a giant hand extended as a platform, it offers a suspended moment over the stream. The Glass House is a look-at-me place if ever there was one. Visitors are surprised at its substance—it is much more than an ephemeral moment to be summed up in an after-dinner anecdote. It conjures questions about place and home; its pristine, uncluttered character conveys a sense of clarity about the relationship between dwelling and place.

Fallingwater may be the most admired house of the twentieth century, but the most-remarked-upon superlative surely falls to the Glass House. It’s loved by many, it has intrigued countless visitors—but if words were stones, the house would long ago have become a steel frame surrounded by shattered plate glass. Instead, it survives, along with Fallingwater, two country houses that together lure roughly half a million people a year through their doors. One may be, to borrow a phrase from a nineteenth-century travel writer, an “incident in the landscape,”43 but the other must be seen as an “episode in the history of twentieth-century architecture.”44

Johnson wrote few melodies but he was a great orchestrator. Well before Johnson became as well-known for his bons mots as for his buildings, his work was described as having an “epigrammatic quality,” one that suggested the “application of a critical and evaluative intelligence rather than the inventions of an inductive creative imagination.”45 But Johnson made himself a powerful cultural tastemaker: When he arrived on the architectural scene, the steel-and-glass towers that today define the modern city did not exist. Johnson was Modernism’s midwife and the man who introduced Miës to America.

Rather against his will, Johnson evolved into one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s most important public admirers. As a man who worshipped the zeitgeist, he found that his old nemesis’s ideas retained remarkable vibrancy. As he came to recognize the importance and the value of their odd alliance, he also grasped that Wright’s work transcended style and even time. Though it rendered his work inimitable, Wright’s genius was, quite simply, of a greater magnitude than Johnson’s.

(John Dolan)

Today, more than half a century after his death, Wright remains America’s best-known and most admired architect. By the time Johnson died, barely a decade ago, he had become what he himself disparagingly called “the famous architect.”46 With his death, his fame began to recede; inversely, Wright’s clearly grows. Yet their connection, in death as in life, enriches our understanding of both grand men of American architecture.