THE POWER OF THE DESERT, OF THE PLANET, SURGES LIKE ELECTRICITY UP THROUGH MY BOOTS (VIETNAM-STYLE JUNGLE BOOTS, OLD AND WORN) TO HEART AND HEAD AND OUT THROUGH SONG INTO THE MOONY SKY, COMPLETING THE CIRCUIT.

—“A Walk in the Desert Hills” in Beyond the Wall, Edward Abbey

Feet are marvelously complex, both flexible and tough, but if they are to carry you and your load mile after mile through the wilderness in comfort, they need care and protection. More backpacking trips are ruined by sore feet than by all other causes combined. Pounded by the ground and bearing the weight of you and your pack, your feet receive harsher treatment than any other part of your body.

This chapter covers the generic styles of hiking boots and shoes, the critical process of fitting footwear, how and of what materials footwear is constructed, and finally models and brands. (A note on terminology: by shoes, I mean footwear that does not cover the ankles; anything that does is a boot.)

Feet come in different shapes as well as sizes.

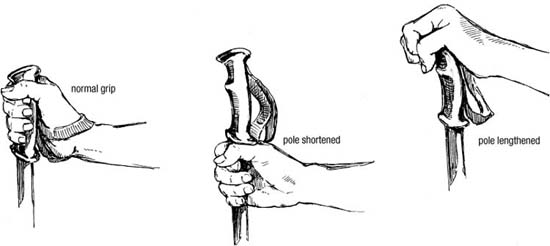

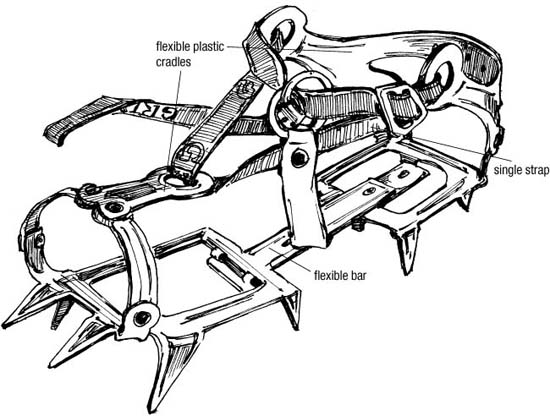

A variety of accessories can make walking easier and safer—from staffs to socks and, for snow travel, ice axes, crampons, snowshoes, and skis. Though snowshoes and skis aren’t walking accessories per se, they make travel in deep snow much easier, especially with a heavy pack. The end of this chapter covers all these accessories.

The main purposes of backpacking footwear are to protect your feet against bruising and abrasion from rough wilderness terrain, to cushion your soles from the constant hammering of miles of walking, and to provide good traction on slippery, steep, and wet terrain.

Protection for the sole of the foot comes from layers of cushioning; these layers must be thick enough to prevent stones from bruising the feet but flexible enough to allow natural heel-to-toe movement. Thick soles also insulate against snow and cold ground and the heat of desert sand and rock. The tread of the outer sole offers grip; the best soles not only give security on rough terrain but also minimize damage to the ground.

Footwear should also support your foot and ankle, though this is less important than some people think. Support comes from a fit snug enough to keep the foot from slipping around inside the shoe but not so tight that it won’t allow the foot to swell. The ankle is supported by a stiff lower heel counter, or heel cup (see Heel Counters and Toe Boxes, page 56, and the illustrations on page 57), and not simply by a high-cut boot; some running shoes give more ankle support than some boots do.

Keeping your feet dry isn’t a major purpose of footwear. Top-quality leather is fairly water resistant, but only boots with waterproof-breathable membrane linings can be considered waterproof. How long they stay so is open to question, however, and they have other disadvantages. Plastic and rubber boots are waterproof, of course, but they make your feet hot and sweaty except in snow.

Once upon a time, virtually all boots were what we now call heavyweight—with leather inners and outers, leather midsoles, steel shanks, and heavily lugged rubber soles. A typical pair of size 9s weighed at least 4 pounds, and it took dozens, if not hundreds, of miles of walking to break them in. A few lighter boots were available, but they were neither very supportive nor very durable.

Lightweight boots mean less weight to lift with each step.

The introduction of lightweight leathers, synthetic fabrics, and running shoe features in the early 1980s revolutionized hiking footwear. Most backpackers were won over, though some stayed—and still stay—loyal to the old heavyweights, and the lightweight versus heavyweight debate has rumbled on ever since. I am firmly on the side of lightweight footwear. My conversion came during a Pacific Crest Trail through-hike in 1982. I set off from the Mexican border in heavy traditional boots that soon gave me hot, sore feet. After just a few days, I ended up carrying them and wearing running shoes (brought along for campwear) much of the time. The heavy boots were more comfortable on my back than on my feet. Only in the snow of the High Sierra did I need them. After 1,500 miles, when the running shoes were just about worn out, I replaced both boots and shoes with a pair of the then-new fabric-suede hiking shoes, Asolo Approaches. These weighed less than half as much as my boots. The staff in the store where I bought the shoes were horrified to hear that I intended to backpack more than a thousand miles in them. But my feet rejoiced at being released from their stiff leather prisons, and my daily mileage went up. Although they were full of holes by the end of the trip, the shoes gave me all the support and grip of my old boots and vastly increased my comfort. I have never since worn heavy traditional footwear for summer backpacking.

That lighter footwear is less tiring seems indisputable. The general estimate is that every pound on your feet equals 5 pounds on your back. If that’s correct, and it certainly feels like it, then wearing 2-pound rather than 4-pound boots is like removing 10 pounds from your pack. Boots weighing more than 3 pounds make my feet ache after about twelve miles, and after fifteen miles all I want to do is stop. Yet in shoes that weigh half as much, I can cover twice that distance before my feet complain. This isn’t surprising when you consider that I lift my feet about 2,500 times a mile (my hiking stride is about two feet long). That means I’m lifting 7,500 pounds per mile when I wear 3-pound boots but only 3,750 pounds when I wear shoes that weigh a pound and a half. Over fifteen miles that’s 112,500 pounds lifted with the boots versus 56,250 pounds with the shoes, an enormous difference.

Heavier boots usually also mean thicker materials and more padding. In all but winter conditions this can give you hot, sweaty feet, which swell and ache and are more apt to blister.

The ultimate in weight saving is to wear no shoes at all. This might seem like a good way to hurt your feet, but in warm weather walking barefoot is perfectly feasible. I occasionally walk short distances barefoot when my feet feel hot and sweaty in my shoes, and I often wander around camp barefoot. Wearing sandals (as I do for most summer hiking) is close to going barefoot. If you’re interested in this idea, Richard Frazine’s The Barefoot Hiker is worth reading (see also barefoot ers.org/hikers).

One of the main arguments for heavy, stiff footwear is that you need it for ankle support when carrying a heavy pack or hiking on rough terrain. This is not true.

To begin with, most walking boots offer little ankle support, since their soft cuffs give easily under pressure. (Try standing on the outer edge of the sole of a standard walking boot and you’ll feel the strain on your ankle.) Only boots with high, stiffened cuffs give real ankle support. My plastic telemark ski boots give good ankle support; I can balance on the edges without strain and traverse steep, icy slopes on my skis without my ankles’ aching. But the stiff ankle support restricts foot movement so much that when I walk in these boots I loosen the clips to let my ankles flex fairly normally. Stiff-ankled boots and natural foot movement do not go together.

What actually holds your ankle in place over the sole of a shoe is a rigid heel counter, or heel cup, found in good-quality running shoes as well as most hiking footwear (see Heel Counters and Toe Boxes later in this chapter, page 56). I once tested a pair of high-top leather boots without heel cups. On rough terrain they were worse than useless—my foot constantly slid off the insole, and my ankle kept twisting sideways. I ended up using them only on good paths between campsites. For mountain ascents, I wore the running shoes I’d brought along as campwear—their heel cups made them more stable than the boots.

Some of the greatest strain on your ankles occurs when you run over steep, rough ground. Yet mountain runners, who do this regularly (sometimes for days on end), never wear boots. Try running in boots and you’ll see why. For traversing steep, rugged terrain, you need strong, flexible ankles and lightweight, flexible footwear. Doing exercises to strengthen your ankles is better than splinting them in heavy, rigid boots.

The other argument in favor of heavy boots is that stiff soles protect your feet from rough terrain and help support heavy loads. I disagree. In my experience, restricting normal foot movement with stiff soles makes me feel unstable and insecure. Lateral stiffness—from side to side—is fine, though not required on most trails, since this stops the footwear from twisting under your feet when you traverse steep terrain. Heel-to-toe stiffness is what restricts natural foot movement.

Stiff soles can’t flex enough to accommodate to the terrain. I find they prevent me from placing my feet naturally, leading to a slow and clumsy gait, which could lead to injury, since your feet are repeatedly forced into the same unnatural position. Also, straining against the stiffness requires energy and is tiring.

What really protects against rough terrain is footwear that cushions your feet and stops stones and rocks from bruising them. The best way to do this is with a hard but flexible thin synthetic midsole plus a shock-absorbing layer. Most lightweight boots and shoes have soles like this.

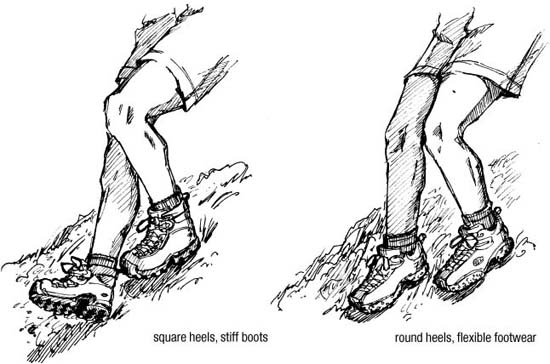

In flexible footwear you can place your whole sole in contact with the ground, even on steep terrain, rather than digging in your heels or boot edges, which jars your legs, can make you unstable, and often gouges holes in the hillside.

Sole stiffness is required only on steep, hard-packed snow. Then a bit of stiffness makes it easier to kick the boot toes and edges into the snow.

Boots and shoes are complex constructions, and there are many ways of making them, using many different materials. You can buy and use footwear happily without knowing whether it has a “graded flex nylon midsole” or “EVA wedges” or is “Blake sewn.” (I’ll explore the more relevant terms in the Footwear Materials and Construction section later in this chapter.) What may be more important to you is whether the boots contain any recycled materials (many now do). The selection is enormous (a recent gear guide lists forty-two hiking footwear companies and more than four hundred models, and this isn’t comprehensive). Choosing footwear can be daunting. But if you go to a store that has a good selection and a knowledgeable, helpful staff trained to fit boots, you can’t go far wrong. Those who want to know more will find information about materials and construction below.

Shoes designed for trail running and adventure racing make ideal lightweight backpacking footwear, as do the hiking shoes made by many boot companies, often described as cross-trainers, trail shoes, or multisport shoes, suggesting that the makers are not sure what they’re actually for or whom to aim the marketing toward. Construction usually features suede-synthetic fabric uppers, often with large mesh areas for breathability, shock-absorbing midsoles, and strong heel counters. Because these shoes are not very warm, I wouldn’t recommend them for snow or very cold weather, but for summer trails, dry or wet, they’re a good choice. I wear them anytime I think sandals might be too cold or not quite protective enough.

Some trail shoes incorporate toe boxes, graded (for flex) nylon midsoles, and even half-length metal shanks (for explanations, see Footwear Materials and Construction later in this chapter). These weigh more than simpler designs but also give a little more protection.

A trail shoe (Merrell Exotech).

Shoes weigh from 20 to 25 ounces a pair for the lightest running shoes to 40 ounces or so for the heaviest trail shoes. (Be wary of look-alike street shoes, which probably won’t stand up to back-country use for long, and of road-running shoes without enough tread for good grip on rough, wet ground. To avoid these, buy from a reputable backpacking gear retailer.)

Trail shoes are usually designated as suitable for easy to moderate trails with light loads. I think this does them a disservice. I’ve carried heavy loads—50 to 60 pounds—over rugged mountain terrain in trail shoes without trouble.

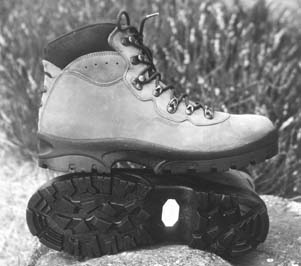

This is the most popular footwear category and has many names, including trekking, trail, off-trail, long-distance hiking, lightweight, and more. The designers hope one of these descriptions will catch your attention. Lightweight boots weigh from 2 to 3 pounds, the lighter end shading into the higher-cut trail shoes, the heavier end into midweight boots suitable for occasional crampon and snow use. The category includes most synthetic-suede boots and quite a few leather ones. The advantages of lightweights are comfort and weight. However, they are not usually waterproof because of the thin materials (except, for a while when new, those with waterproof-breathable linings), and some have many vulnerable seams. Lightweight boots reach the ankle or higher and have protective rands, or bumpers (either full or just at the toe and heel), cushioned linings, sewn-in tongues, graded flexible midsoles, and on some models, half-length shanks. When I wear boots they are usually light ones. They can cope with most terrain except steep, hard snow and ice. I wore a pair of 34-ounce leather lightweights for most of the Arizona Trail with a pack that weighed 70 pounds at one point (six days’ food and three gallons of water). They lasted the 800-mile hike and were very comfortable except on the hottest days, when I wore sandals.

Weighing from 3 to 4 pounds, medium-weight boots are good for mountain and winter backpacking where cold, wet weather is expected and crampons may be needed. The best models combine the durability and support of traditional boots with the comfort of lightweight designs. Although most have one-piece leather construction, a few models are fabric-leather combinations. Most medium-weight boots incorporate a sole stiffener—either stiff nylon midsoles or half-length shanks or both—and can be fitted with crampons for hard snow and ice. Generally these boots are designed to cope with rugged, off-trail terrain in any weather. The best ones are made on curved lasts and feature one-piece top-grain leather, padded sewn-in tongues, heel counters, toe boxes, and shock-absorbing midsoles or dual-density outsoles. Many also include waterproof-breathable sock liners.

The proper fitting of medium-weight boots is critical, and a short break-in period is advisable.

Heavy boots (4 pounds and up) are, in my opinion, too stiff and heavy for most backpacking, though some traditionalists prefer them. But they are good for easy mountaineering—trips that combine hiking with scrambling, easy rock climbing, or long periods of crampon use—the type carried out on easy alpine snow ascents in summer. Light- and medium-weight footwear may be too soft and flexible for these activities, especially crampon use. Even heavyweight designs have modern features, though, with synthetic cushioning midsoles, graded nylon midsoles, footbeds, synthetic linings, curved soles, and shock-absorbing heel inserts.

Heavyweights can require considerable breaking in. I find them uncomfortable and tiring to walk in and wear them rarely—only when prolonged crampon use and step kicking in snow are likely. I can accomplish most of the very easy snow and ice climbing I do when backpacking using medium-weight boots that accept flexible crampons and are far more comfortable on easier terrain; on steep, rocky terrain where scrambling and easy climbing may be required, I find lightweight footwear perfectly adequate. The latest heavy boots are more comfortable than traditional models, though, because of rocker soles and carefully shaped uppers.

Hiking or sports sandals are now my favorite footwear for summer hiking, and I’m using them earlier and later in the season too—whenever there’s no snow—with waterproof-breathable socks for wet cold and wool socks for dry cold. I long ago overcame my first reaction: that they might be fine for leaping out of rafts in the Colorado River but that their only use to the backpacker was as campwear and for river crossings. Once I tried a pair, I quickly became a convert. Not just any old sandals excel for hiking, of course. To be suitable for walking any distance, they have to support the feet, cushion against hard, rough, and hot surfaces, and grip adequately. The best of them do all of this very well.

A hiking sandal (Teva Wraptor 2).

Essential features are thick, shock-absorbing soles with a shaped platform that supports the foot; a deep tread for grip; and a strapping system that holds the heel and forefoot firmly. Straps may be leather, synthetic leather, or nylon webbing. The last two materials absorb little moisture and dry quickly and would be my first choice for wet-weather use. They are usually fastened by hook-and-loop (e.g., Velcro) fabric, though some models use clip buckles.

A broad and fairly rigid heel strap is needed to keep the heel centered over the sole. Some models (Teva Wraptor, Chaco Z1) have instep straps that run over the foot, through the sole, and back over the foot. With these it’s easy to get a very snug fit. I also look for curved or rimmed edges that protect the feet—especially the toes—from bumping against rocks and stones.

Like other footwear, sandals need to fit properly. Your foot shouldn’t hang over the sole at the sides or at the toe or heel, and the straps should hold the foot snugly in place without rubbing. Try sandals on and walk around the store to see if they rub anywhere, just as you would with boots. If you’re going to wear them without socks, you may need a size smaller than your boot size. Stabilizing footbeds like Superfeet won’t stay put in most sandals, so if you need these, sandals may seem a poor choice. But footbeds will fit in Bite sandals such as the X-Trac and the Xtension. I tried the X-Tracs on a six-day, 115-mile hike with Superfeet fitted and found them comfortable, well cushioned, and supportive. Also many sandals have firm, shaped soles that mimic the effects of footbeds.

Although I haven’t had any problems with sandals, they obviously have limitations. They’re fine on trails and most rocky terrain but not so good in spiky vegetation. In deserts you need to take great care to avoid cacti; in forests, thorn bushes can be a problem. Though clearly best suited to warm or dry conditions, they can be worn with wool socks when it’s cool and dry and waterproof-breathable socks when it’s wet. I first learned just how superior sports sandals are to other footwear in hot weather on a trek in the Himalaya, when I wore a pair for more than 75 miles on rugged, steep, stony trails. My feet stayed dry and cool and never felt sore or swollen, nor did I suffer any blisters. Sweaty socks weren’t a problem—I wore socks only when it was cold and in camp. When streams crossed the trail, I sloshed straight through, unlike the others in the party, who had to stop to remove their boots and socks. Wearing sandals toughens your feet, too, as I found at the end of a Nepal trek, when I did a 2,000-foot scree run in them. The stones that slid between my feet and the sandals were irritating, but they didn’t bruise or cut my feet. Really sharp tiny stones, like the pumice found in the Devils Postpile region of the High Sierra, are quite painful, but they would be if they got in your boots, too. An advantage of sandals is that usually you just need to tap the toe on the ground to shake out debris—much quicker than removing boots or shoes.

Since that Nepal trek, I’ve worn sandals for a 500-mile, five-week hike in the High Sierra; two-week trips in the Colorado Rockies, the Grand Canyon, and the High Uinta Mountains in Utah; and innumerable day and weekend hikes. Whereas sandals used to be my backup footwear, now I sometimes carry lightweight shoes for cool evenings in camp or the occasional cold, stormy day. Mostly, though, I make do with socks.

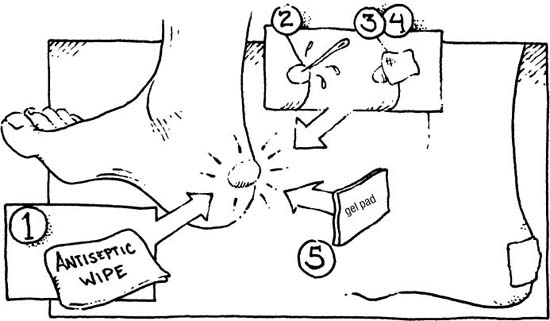

Five weeks is my longest hike in sandals. Others have gone much farther. Scott Williamson walked the Florida Trail and the Appalachian Trail in sandals, plus the country in between, and Hamish Brown hiked the 900-mile crest of the Atlas Mountains in Morocco in sandals. Ray and Jenny Jardine wore sandals over a significant portion of the Pacific Crest Trail, though Ray reported that the soles of his feet dried out on this trip and developed painful, deep cracks that took a long time to heal. On my 500-mile High Sierra hike, I had the same problem, with splits appearing in the tips of my big toes. Sunscreen kept the cracks moist and helped them heal, but one got so bad I ended up covering it with 2nd Skin gel, taped into place. Under this dressing it healed in about a week. It’s wise to apply sunscreen to bare feet anyway. They don’t usually see much sunlight. In sandals they are exposed and, just like any other part of your body, can get burned. Straps can rub, too. If they do, you need a patch of moleskin, Compeed, 2nd Skin, or other hot-spot treatment, just as with boots.

Hiking sandals weigh from 20 to 35 ounces, comparable to hiking shoes. If you just want a pair for campwear, simpler sandals like flip-flops are much lighter.

Take your time when choosing footwear—if the fit isn’t right, you’ll suffer. Nothing is worse than footwear that hurts. You need to consider the types of boots and shoes available, construction methods, and materials, but the most modern, high-tech, waterproof, breathable, expensive boots are worse than useless if they don’t fit. Given the bewildering variety of foot shapes, good fit entails more than finding the right size. It’s unwise to set your heart on a particular model of boot or shoe before you go shopping, however seductive the advertising or the recommendation from a famous hiker, mountaineer, or even backpacking author. Since trying on footwear is essential, this is one item I wouldn’t buy on the Internet or from a mail-order catalog.

All footwear is built around a last, a rough approximation of the human foot that varies in shape according to the bootmaker’s view of what a foot looks like. Lasts sometimes are designated “American,” “European,” or “British,” but these descriptions don’t mean much in the real world and can be ignored.

Since women’s feet are generally narrower and lower volume (less volume relative to the length and width) than men’s, women’s boots are made on different-sized lasts. Men with small, narrow feet may find that women’s boots fit them best, just as women with larger, wider feet may prefer men’s boots.

Curved lasts, which produce a boot with a “rocker” sole, make a big difference, especially in stiff-soled, heavy boots. The curve of the sole rolls with your foot, mimicking the flex of the forefoot and allowing a more natural gait.

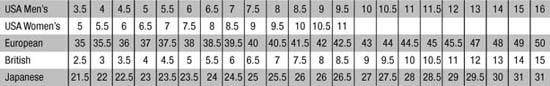

Boot size comparison chart.

Allow several hours for buying footwear, and try to visit a store at a quiet time, not on a busy Saturday afternoon. Feet swell during the day, so it’s best to try on new footwear later in the day. Take your hiking socks with you, but if you forget them, most stores provide suitable socks to wear while trying on footwear. Use your normal shoe size only as a starting point; sizes vary from maker to maker and, just to make matters more confusing, there are different sizing systems. A store may stock footwear made in the United States, Italy, Austria, South Korea, and more, so you can’t expect consistency.

Phil Oren checking the fit on an incline board.

Phil Oren checking heel fit on an incline board.

Make sure you try on both shoes. One of your feet is almost certainly larger than the other, perhaps by as much as half a size. Make sure the larger foot has the best fit. An extra sock or a volume adjuster can pad a boot that’s slightly too large, but nothing can be done for one that’s too small.

Lightweight boots and shoes are fairly easy to fit because they are soft and mold to the feet quickly. Medium- and heavy-weight boots tend to be uncomfortable at first, which makes finding a good fit in the store more difficult. But because they are so unforgiving, a good fit is essential, even though they should eventually stretch a little (in width, not length) and adapt to your feet. Even more care is needed when fitting traditional heavy leather boots.

I used to recommend the standard fitting method—put your finger down the back with the boots unlaced, wiggle your toes, lace the boots, walk around the store, kick something. It was, I thought, good advice. It is in fact totally inadequate. However just like everyone else, I didn’t know any better. I do now. I know that with proper fitting you can get footwear that doesn’t hurt your feet. If you’re one of those lucky people—those lucky few—whose feet and legs don’t hurt, whose boots don’t rub, who don’t get blisters, then you can ignore the next section. For those whose feet may give the occasional twinge, to those for whom blisters and aching feet are major problems, the next few paragraphs could be the most important part of this book.

Proper fitting begins with the feet, not the footwear. The system that has revolutionized boot fitting was developed by Phil Oren after he had problems finding footwear that fit properly for a 750-mile hike on the Pacific Crest Trail. His feet had been damaged by ill-fitting footwear in the past, so standard boots wouldn’t fit him. After having his boots modified at a ski shop, he successfully completed his hike. Along the way he met many hikers with foot problems traceable to poorly fitting footwear, and he started searching for a better way to fit hiking footwear. Since then he has developed a sophisticated fitting system that really does work. Phil and his team train retail staff in boot fitting and run workshops for hikers (sponsored by Backpacker magazine and known as “Boot Camps”). He has also compiled a huge database of foot shapes and sizes and worked with manufacturers on producing better-fitting footwear. If you have any boot problems at all, I recommend finding a store with staff trained in Phil’s FitSystem. (For more on this, see fitsystembyphiloren.com.) I’ve had footwear fitted by Phil Oren and I’ve taken the standard and advanced training workshops. I’m convinced that the FitSystem is the best way to fit hiking footwear.

Everyone’s feet are different, so it’s hardly a surprise that mass-produced footwear is unlikely to fit well without modification. I certainly had problems finding footwear that fit well until I used the FitSystem. These problems increased over the years as my feet appeared to get bigger. I was faced with a choice between footwear that hurt my toes, especially when hiking downhill, and larger sizes that allowed my toes room but didn’t support my ankles or hold my heels in position, resulting in holes in the linings and in the heels of my socks. I went for the larger size, since this was less painful over a day’s hiking, but it certainly wasn’t ideal. Since having a proper fitting, I’ve gone back to my original size without sore toes, and I don’t wear holes in the linings or my socks. Following is a description of the FitSystem and what you should expect from a boot fitter.

A boot fitter should examine and measure your feet before you try on any footwear in order to find out whether you have any fitting problems and which footwear is likely to fit. Information from the examination should be entered on a foot chart, which you can do while being examined. This can be unnerving, as I discovered when Phil examined my feet and informed me I had (slight) hammertoes, Morton’s toe, chubby toe, toe drift, calluses, and the beginnings of bunions. Ouch! Would I ever walk again?

Next comes the toe test, which is done standing, so the feet are bearing weight. The fitter tries to lift your big toe off the ground with a finger placed under its tip. If your feet are aligned properly, the toe should move easily. If, like mine, it seems glued to the ground, your foot is overpronated. To check this, the fitter twists your knee outward, putting the foot into the neutral position. The big toe should now be flexible.

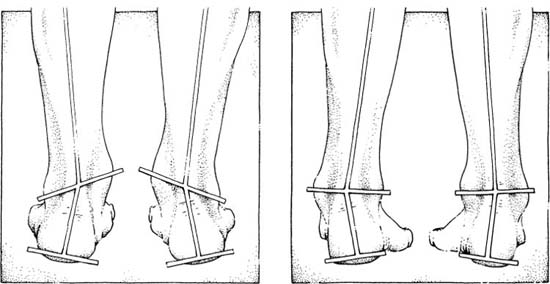

Overpronation (left) and oversupination (right).

The biomechanics of walking explains what the toe test tells us. As you walk, the shape of your foot changes constantly. All footwear interferes with this. When your foot is in midstride, with no weight on it, it’s in the neutral position. When your heel hits the ground, your foot rolls to the inside and the arch flattens slightly. This pronation allows the foot to adapt to rough, uneven surfaces; remember that our feet were designed for walking on soil, grass, stone, sand, and other natural terrain, not flat, smooth, man-made surfaces. As your foot flattens against the ground, it should go into neutral and stiffen for stability and forward movement. As your heel lifts off the ground, your foot becomes a rigid lever with a high arch and instep so you can spring forward off your big toe. This is called supination (oversupination can occur but is very rare). After years of wearing unsupportive footwear and walking on pavements and floors, instead of going into neutral and then becoming slightly supinated, the foot often just flattens out (overpronation). In this position your foot is locked to the ground with no spring in the toes (hence the toe test). To take your next step, you have to move from the inside of your foot rather than from your toes. When you do this the foot tends to turn slightly outward, which distorts the skeletal structure, twisting the ankle, knee, and hip when they should be aligned. This unstable posture can lead to joint problems. When your foot overpronates it also elongates, which makes boot fitting very difficult. Do you fit to the shorter, neutral position or the longer, overpronated one? That was my problem. This elongation can be shown by drawing around the foot while it is weighted and unweighted and comparing the two outlines. It’s then easy to see that the same boot can’t fit both shapes. Phil Oren’s data show that overpronation affects about 80 percent of us, so it’s a major bootfitting issue.

The toe test shows whether you overpronate. But that in itself doesn’t help much with boot fitting. Next you need to know what size your feet are and what difference overpronation makes. Each foot should be measured with the Brannock Device (an instrument for measuring foot length and width) for overall length (heel to toe) and for heel-to-ball length, which is important because boots should flex where your foot does. The measurements should be taken with the foot weighted and again with it unweighted and in the neutral position. The width of your feet should be measured too. Each of my feet varied by one size in total length and one and a half to two sizes from heel to ball. That explained why my feet appeared to be getting bigger. They weren’t; they were overpronating and elongating when weighted.

Foot volume is important too, but this has to be estimated; the Brannock Device cannot measure volume. My feet are low volume, and I have narrow heels and very narrow Achilles tendons. However, my feet are also quite wide, so I need footwear that is wide across the metatarsals (the base of the toes) but low in volume and narrow at the heel.

If your feet overpronate, and chances are they do, they need stabilizing if your footwear is to fit properly. This can be done with footbeds that support the foot and hold it in position, which means junking the soft foam inserts found in most boots and shoes. These “footbeds” provide no support and don’t stabilize the feet. Just try pushing your finger against the sides of the heel section while holding the center down with the other hand. With virtually all inserts that come in footwear, the sides collapse easily. They’ll do the same under your foot. (Montrail footwear has the only half-way decent boot inserts I’ve seen. They’re not as good as a proper footbed, but they’re far better than most.)

There are several types of stabilizing footbeds (Conform’able and Sole Custom are two) as well as prescription orthotics. The ones I use are Superfeet footbeds. They have a hard plastic and cork rear and midsection that holds the heel in place, minimizing foot movement and overpronation. There are two types: off-the-shelf footbeds, called Trim to Fit, and Custom Fit. Trim to Fit footbeds can stabilize the foot 40 to 75 percent, and Custom Fit ones stabilize it up to 95 percent. Due to my level of overpronation, I wear Custom Fit Superfeet. To make these, the fitter holds the foot in the neutral position (footbeds made with the feet weighted will fit the overpronated foot, which you don’t want). The footbeds, which are partially shaped already, are heated and then held under your feet in plastic bags. All the air is then sucked out of the bags—a slightly peculiar sensation—while the footbeds mold to your feet.

Since your feet are so firmly supported and no longer move in your footwear, stabilizing footbeds can feel strange and even uncomfortable at first. It may be a good idea to wear them for just a few hours at a time until you adjust, though I could wear them all day immediately. Once the footbeds are fitted they can be transferred from one pair of shoes or boots to another, and I now put them in all my footwear. I now take a smaller size because my feet no longer elongate much when weighted. I can stride off my toes too, rather than the insides of my feet, so I’ve lost that slightly splayed duck-footed walk I had. My feet ache less because the footbeds prevent the cushioning fat pad under the heel from flattening and spreading sideways when weighted, and my knees ache less on long descents because my ankles, knees, and hips are properly aligned.

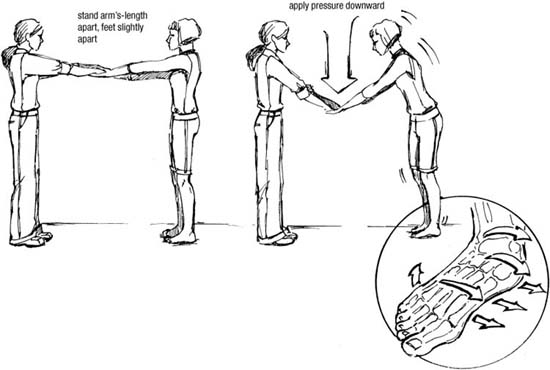

To test your alignment, stand with your feet slightly apart and your hands held out in front of you, one over the other. Have a friend slowly press down on your hands. If you overpronate you’ll lose your balance quickly and feel very unstable. Next stand on a pair of stabilizing footbeds and repeat the test. With your joints properly aligned, you should be able to resist the downward pressure without much effort.

Testing proper alignment.

To demonstrate the fat pads, get a friend to push her fingers against the base of your unsupported heel. She should be able to feel the heel bone easily. Then have her squeeze the sides of the heel together with the other hand and press with her fingers again. This time the fat pad will prevent her from feeling the bone. Stabilizing footbeds do the same. If your feet don’t overpronate, these tests won’t show much difference, and you won’t need stabilizing footbeds.

Stabilizing footbeds will have an effect only if your footwear fit properly. If they are too roomy, the footbeds alone won’t stop your feet from moving in them. For that you’ll need to reduce the boots’ volume by wearing thicker socks; by putting a solid, noncompressible flat piece of neoprene, called a volume adjuster, under the footbed; or by placing a piece of soft rubber under the laces to push the tongue down on the foot when the laces are tightened (a tongue depressor). These methods can make boots and shoes with too high a volume fit better, but it’s best to have a good fit to start with. Luckily that is easier than it used to be. Since Phil Oren’s FitSystem came to prominence, some boot-makers have altered the shape of their lasts and reduced the volume of their footwear so they are more like most people’s feet. Certainly I more often find footwear that fits well.

Once your feet have been inspected and measured and the fitter has decided whether you need stabilizing footbeds or other accessories, it’s finally time to try on some footwear. It’s best to wear your hiking socks for this. Don’t, even now, expect to find a perfect fit: as close as possible is what you’re looking for, meaning a boot that approximates the shape of your foot in volume and width as well as length. Beware of boots that are too big. These tend to feel comfortable because they don’t press anywhere on your feet, but in use they’ll rub and be unsupportive. Boots should fit snugly around the heel, ankle, and instep but have room for you to wiggle your toes. They should flex at the same point as your feet do so you don’t have to fight them every time you take a step, which is tiring and may make your feet slip inside your footwear.

Once you’ve found a rough fit, you need to try the boots on a 20-degree ramp known as an incline board. Lace the boots firmly, then stand facing up the board while the fitter checks that the boot heels fit properly and sees whether there is any space or loose fabric around the instep and ankle, showing that the boot has too much volume. The fitter should also mark on the boots with chalk or a piece of tape the points where they flex and, by feeling for the first metatarsal head at the base of your toes, check whether your feet flex in the same place. Once this is done, you face down the incline board and jump up and down before the fitter again checks to see if your feet have moved much in the boots. If they have, the boots have too much volume. This can be solved as described earlier, but it is preferable to try lower-volume footwear instead.

The footwear that fits your feet best is still unlikely to fit exactly. A good fitter should be able to modify footwear to achieve a custom fit. Pressure points, often around the flex point, are the main problem. Boots can be stretched to remove them, using the blunt end of a bent metal rubbing bar to gradually ease out the leather or fabric. Just a tiny modification can have quite an effect on the fit. Since I test boots for a hiking magazine, I have my own rubbing bar at home so I can stretch boots that are too narrow for me. This has let me test many boots that would otherwise have hurt my feet. Occasionally there may be tiny bumps inside footwear due to manufacturing anomalies. With the boot on the rubbing bar, these can be flattened with a convex hammer.

Adjusting a boot-stretching device to the correct foot shape.

Jeff Gray of Superfeet placing a boot (without the footbed) in hot water to soften it for modification.

Jeff Gray stretching a boot.

Although leather can be stretched on the rubbing bar, you can’t stretch hard, synthetic toe boxes and heel counters or rubber rands (see under Footwear Materials and Construction below) without heating them first to soften the material. This can be done by sealing the boots in a plastic bag and dunking them in a large pot of boiling water. Various hydraulic devices can then be used along with the rubbing bar to stretch the boots.

For the fit that is closest to perfect, you can have casts made of the front or rear of your foot and then inserted into footwear to stretch it to the exact shape of your feet. Although initially expensive, the casts can be used for all your footwear.

A good boot fitter should make any required modifications when you buy footwear. If you already have footwear that doesn’t fit properly, you can take it to a store to be modified. Phil Oren believes that most footwear needs modification of some sort to get the best fit.

I suggest going through the fitting process every time you buy new hiking footwear even if it is the same model. Manufacturing processes can change, and new lasts may be used. I’ve found that models that once fitted me well didn’t do so a few years later. I discovered that a different factory was producing them and that the fit had indeed changed slightly. If you keep the details of your foot examination and measurements, this process doesn’t need to be done every time, though it’s worth an occasional check to see if anything has changed, especially if you have any foot problems. It’s advisable to always fit footwear using any accessories you expect to use with them, such as stabilizing footbeds.

When you get your new footwear home, wear them inside for a few hours or even a few days just to check that they really do fit. A store should exchange footwear that haven’t been worn outside. Once they’re muddy and scuffed, they’re yours.

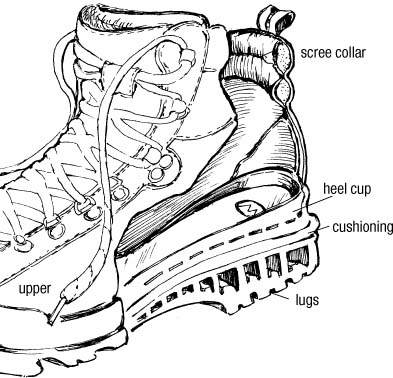

There are two basic parts to a boot or shoe: the uppers, which are flexible and mold around the foot; and the sole, which is more rigid and lies under the foot. The sole is usually made up of a number of layers. The insole lies under the footbed and is usually quite thin. The midsole lies between the insole and the outsole and may itself consist of several layers of shock-absorbing and stiffening materials. The outsole contacts the ground and has a tread cut into it. The uppers and the sole are made separately and then attached via the construction method.

Making a foot cast.

Foot casts can be used to ensure that footwear fits properly.

Leather is still the main material for uppers, though synthetics now dominate midsoles and linings and fabric-leather combinations are standard for running and trail shoes and common in the lightest boots. Leather lasts longer than other upper materials, keeps your feet dry longer, and absorbs and then disperses moisture (sweat) quickly and efficiently. It is also flexible and comfortable.

Although fancy names abound, there are two basic types of leather: top-grain and split-grain. Top-grain leather, made from the outer layer of the cow’s hide, is tougher and thicker and holds water-repellent treatment and its shape better than split-grain leather, which is the inner layer of the hide. Split-grain leather is often coated with polyurethane or polyvinyl chloride (PVC) to make it more water resistant and attractive. However this shiny layer soon cracks and allows the leather to soak up water like a sponge, while the remaining coating impedes drying. Full-grain leather is the full thickness of the hide. It’s very tough and water resistant but also thick and heavy, so it’s rarely used in boots, although the term is often used for top-grain leather. Nubuck (also spelled nubuc and nubuk) is top-grain leather that has been sanded and polished to give it a smooth finish somewhat similar to suede. It’s much tougher and more water resistant than suede, which is split leather with the inner surface turned outward and brushed. Nubuck is popular with bootmakers because it shows scuffs and scratches less than smooth leathers do and has a sensuous feel. Some top-grain leather boots have the rough inner surface of the leather facing out, though this is less common now that nubuck is available. Rough-out and nubuck leathers are easily distinguished from suede by their thickness and solidity. Suede is often used to strengthen the wear points of fabric footwear. Although it is not as durable, supportive, or water resistant as top-grain leather or the best split leathers, good-quality suede is still worth considering for lightweight footwear.

Leather comes in various thicknesses, always measured in millimeters—inches just aren’t precise enough. Heavyweight mountaineering boots usually have 3-millimeter leather, light hikers 2-millimeter or less.

To make it usable in footwear, all leather has to be tanned—treated with chemicals or oils. With some leathers a water-repellent substance—usually silicone—is chemically bonded to the fibers during tanning. This leather goes by various names, such as HS12, Prime WeatherTuff, and Pittards WR100. I’ve found that this leather performs as advertised, especially when new, and is nearly waterproof. In time, though, the waterproofing breaks down and waxing (for more on this, see Waterproofing and Sealing later in this chapter) is required.

Many lightweight boots and trail shoes copy the nylon-suede design of the running shoes they were based on. This works well in all but the coldest, snowiest conditions. Uppers are mostly fabric, often nylon mesh in shoes but usually textured nylon in boots (though sometimes polyester), reinforced with leather, suede, or synthetic leather. This design requires many seams, which are vulnerable to abrasion and thus may not be durable in rough, rocky terrain, where boot uppers take a hammering. (I found this out the hard way many years ago while scrambling and walking on the incredibly rough and sharp gabbroic rock of the Cuillin Ridge on Scotland’s Isle of Skye. After two weeks, my nylon-suede boots were in shreds, and virtually every seam had ripped open.)

Waterproofness is not a strong point of fabric-leather footwear either, unless they are lined with a waterproof-breathable membrane. This is again mostly because of the seams but also comes from the thinness of the materials. Grit and dirt can penetrate nylon much more easily than leather, however, so such membranes do not last as long in synthetic boots as in leather boots, whether they are lightweight nylon or the much tougher Cordura. I like synthetic leather for trail shoes, but for lightweight boots I prefer all leather since I wear boots only in terrain I feel is too rugged for shoes.

So why consider fabric-leather footwear at all? Because it’s cool in warm weather (as long as there’s no membrane), it needs little or no breaking in, it’s comfortable, and it dries more quickly than heavier footwear. It’s also used on many of the lightest, most flexible shoes.

Many sandals, some shoes, and a very few boots (such as the Garmont Vegan) use synthetic leather for the uppers, often in combination with nylon. Synthetic leather is flexible and mimics fairly well the performance of split-grain leather, though not top-grain. It has the advantage of being nonabsorbent and therefore quick drying, but it’s not very breathable.

Plastic is now the dominant material for mountaineering boots, alpine ski boots, and telemark ski boots because it’s better than leather at providing the rigidity, waterproofness, and warmth such pursuits require. But hiking boots need to be flexible and permeable to moisture so that sweat can escape. I’ve hiked in plastic telemark and climbing boots, and I’ve never had such sore and blistered heels or such aching feet. With their rigid soles and outer shells, such boots work against your feet rather than with them. Now when I hike to the snow in my plastic telemark boots, I undo the clips on the uppers to allow my feet to flex. This isn’t very stable, but it’s less painful than keeping the boots done up. Plastic hiking boots have appeared in the past but soon vanished, since they were too hot and sweaty.

Heels need to be held in place and prevented from twisting, and toes need room to move and protection from rocks and other natural protuberances. Heel counters, or heel cups, are stiff pieces of material—usually synthetic, though sometimes leather—built into the rear of boots or shoes to cup the heels and hold them in place. You usually can’t see them, although some makers put them on the outside of some footwear, but you can feel them under the leather of the heel. Heel counters are essential. A soft, sloppy heel without a counter won’t support your ankle, no matter how high the upper.

Toe boxes are usually made from similar material inserted in the front of a boot; some boots dispense with this construction in favor of a thick rubber rand around the boot toe.

Traditionally, linings were made from soft leather—as they still are in some boots—but lighter, less-absorbent, harder-wearing, quicker-drying, moisture-wicking, nonrotting synthetics are taking over. The main one is Cambrelle. I find these new linings superior to their leather counterparts (unless the boots have waterproof-breathable membrane linings, as discussed below, in which case leather protects the membrane better). Some wearers have found an odor problem with synthetic linings, but that hasn’t occurred in the footwear I’ve used.

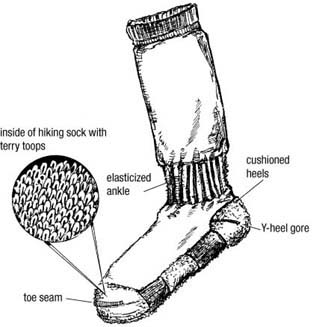

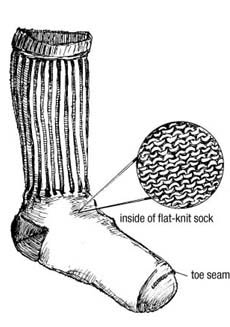

Many boots have a thin layer of foam padding between the lining and the outside, usually around the ankle and the upper tongue, but occasionally throughout the boot. Such padding does provide more cushioning for the foot, but it also makes boots warmer, something to be avoided in hot weather. Foam also absorbs water and dries slowly. I prefer boots with minimum padding; I rely on socks for warmth.

Many boots now feature linings, sometimes called booties, made from vapor-permeable waterproof membranes such as Gore-Tex and Sympatex. These certainly make the boots waterproof when they are new, but once the membrane is torn or punctured, it will leak. How long they keep water out varies. The membrane itself is fragile, and if your feet move in your boots, the membranes can wear out very quickly. Some people swear by them, others swear at them. My experience suggests that such linings last longest and perform best in boots that have few seams and are made from leather rather than nylon and suede. Membranes laminated to leather are less likely to be cut by tiny specks of sharp grit than those laminated to more open-weave synthetic fabrics. The first membranes leaked fairly quickly, sometimes after only a few weeks’ use, but newer ones do last longer. I have a pair of trail shoes several years old that have had months of use and are still waterproof. Even so, good-quality footwear should long outlast a membrane lining.

Cross section through a three-season boot.

Waterproof-breathable membranes have another big disadvantage. Although they let some water vapor out, they are far less breathable than footwear without them. Thus they are hot and sweaty in warm weather, especially if the uppers get saturated—which is why water-repellent leathers are best for the outside. And if you do get them wet inside (say, by stepping in a deep pool or creek), they are slow to dry, because although vapor can pass through the membrane, liquid cannot. There are better ways to keep your feet dry (see Waterproof Socks, pages 78–79).

A few boots have nonbreathable waterproof liners. These are suitable only for cold, wet conditions, and even then your feet can get quite wet from sweat. I’d avoid these boots.

Sewn-in, gusseted tongues with light padding inside are the most comfortable and water resistant, and they’re found on most footwear; the only disadvantage of gusseted tongues is that if you’re not wearing gaiters, snow can collect in the gussets and soak into the boots. Oxford construction is a better design for snow: two flaps of leather (basically extensions of the upper) fold over the inner tongue, which may or may not be sewn in, often held in place by small hook-and-loop tabs. Some heavier boots achieve the same purpose by a gusseted tongue with another tongue behind it, sewn in only at the base. On high-ankle and stiff leather boots, the tongue may be hinged so it flexes easily.

Boots may be laced up using D-rings, hooks, eyelets, webbing, miniature pulleys, and speed lacing (tiny metal tunnels through which the laces can be pulled quickly). D-rings may be plastic and sewn to the upper (the norm on shoes and ultralight boots) or metal and attached to a swivel clip riveted to the upper. The easiest system to use combines two or three rows of D-rings at the bottom of the laces with several rows of hooks or speed lacing at the top. With this system you can open the boot fully at the top yet tighten the laces quickly. This advantage is not trivial when you’re trying to don a stiff, half-frozen boot in a small tent while wearing gloves, with a blizzard outside. Boots with D-rings alone involve far more fiddling with the laces and are harder to tighten precisely. Some boots use tiny pulleys instead of D-rings. These make it very easy to adjust the fit evenly across the foot. Whatever the type of lacing, many boots have a locking hook offset at the ankle that holds the lace in place even when it’s undone. The offset position allows you to tighten the boot around the instep to stop your foot from slipping.

Old-style eyelets are rare on boots now, though they are still found on some shoes. Although they are the most awkward system to use, eyelets are the least susceptible to breakage. Shoes often have webbing loops for laces, and these are starting to appear on boots.

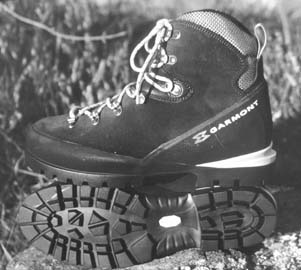

My current winter boots (5-pound high-topped leather monsters, but good with crampons) have four rows of speed lacing, one set of metal D-rings, one set of offset webbing loops, and two rows of hooks. My lightweight hikers (2 pounds, 2 ounces, leather) have two rows of speed lacing, offset locking hooks, and two rows of hooks. And my trail shoes (1 pound, 11 ounces, mostly mesh with synthetic leather reinforcements) have one speed-lacing tunnel, a pair of synthetic leather loops, and three rows of speed lacing. The single lacing tunnel allows the lower lacing to run asymmetrically across the foot, following the flex line, rather than straight across, a sensible innovation first introduced by Garmont. All these lacing methods work well, enabling me to lace the boots quickly and adjust the tension so the footwear fits snugly.

Laces are usually made from braided nylon, which rarely breaks, though it may wear through from abrasion after much use. Round laces seem to last longer than flat ones, though not by much. I used to carry spare laces, but I gave it up long ago; it’s been years since I had a lace snap, even on long walks. If one ever does, I’ll replace it with a length of the nylon cord I always carry.

Whatever the type of lacing system, footwear must be laced properly if it is to support your feet. The laces should hold the footwear snugly around the forefoot but not be too tight across the instep, which can hinder the forward flex of the ankle. Loose laces allow the feet to move in the footwear; too-tight laces are painful.

Many boots have one or more rolls of foampadded soft leather or synthetic material at the cuff to keep out stones, grass seeds, mud, and other debris, but for this to work well the boots have to be laced up so tightly that they restrict ankle movement. The collars themselves don’t seem to cause any problems, so their presence or absence can be ignored when choosing a boot.

Conventional wisdom says the fewer seams, the better, because seams may admit water and can abrade, allowing the boot to disintegrate; thus one-piece leather boots with seams only at the heel and around the tongue should prove the most durable and water resistant.

I agree. Having used quite a few pairs of shoes and boots made from several pieces of stitched fabric and leather, I’ve found their life expectancy limited by how long the seams remained intact. Side seams usually split first. (This can be postponed, but not prevented, by coating them heavily with a seam sealer or quick-setting flexible epoxy, which also decreases the likelihood of leaks.)

I don’t rely solely on one-piece leather construction for footwear, however, as it’s usually found only in medium to heavy footwear. But for long treks in cold, wet conditions, I still prefer one-piece leather boots. It’s a difficult trade-off. I learned this the hard way. Walking the length of the Canadian Rockies, I used two pairs of sectional leather boots from different makers; they both split at the side seams after about 750 miles. I guessed that only a one-piece leather boot would have lasted the whole walk, so two years later, when I set off on a thousand-mile walk across the Yukon Territory, I wore one-piece boots. They lasted the whole trip.

However, it’s debatable whether you should wear just one pair of boots or shoes for an entire long-distance hike. I now think you should change footwear after a while because the internal structure can begin to break down and the cushioning in the sole can compact. This is especially so with midsoles made from Evazote (EVA), a closed-cell foam, and similar materials. Heavier boots are generally more durable, but even they will change shape eventually and may no longer fit so well.

Most boots and shoes have a removable foam insert, sometimes incorrectly called a footbed or an insole. Some are made from dual-density foam or have pads of shock-absorbing material built into the heel and forefoot for cushioning. Thicker inserts made from shock-absorbing materials such as Sorbothane are said to improve cushioning. Some of these inserts are relatively heavy, adding up to 5 ounces to the weight of footwear, and they may also be hot in warm weather. I used to use such inserts but found they didn’t last. Since they don’t support your foot, the cushioning they give is mostly illusory, as your foot can still flatten out and overpronate. For real support, you need a stabilizing footbed (see Stabilization and Footbeds, pages 49–51).

If your feet tend to swell a lot (as is likely on long-distance walks and in hot weather), removing the inserts will make your footwear roomier. I’ve often done this toward the end of a long day. Inserts and footbeds get damp from sweat during the day, and moisture can accumulate beneath them, so taking them out each evening to let them and the boots dry is a good idea. Don’t put them near a fire or other heat source, though—they melt very easily.

The boot sole must support the foot, protect it from shock, and be flexible enough to allow a natural gait, but it doesn’t need to be stiff. Extensive hiking over rugged terrain in sandals and flexible trail shoes has convinced me that flexibility is more important.

The upper layer of the sole is the insole, or lasting board, a flat, foot-shaped piece of material. Shoes with this layer are described as being board-lasted because the board is fixed to the last and the shoe built around it. The stiffness of a shoe or boot is in part due to the material the board is made from. A flexible fiberboard insole (which may be made from pressed wood pulp or may be synthetic) is common in running and trail shoes and the lightest boots. In inexpensive footwear, the insoles may be cardboard. (There are reports of cardboard insoles breaking up when wet, though this hasn’t happened to any I’ve used.) Much hiking footwear now has torsionally stiff plastic or nylon insoles graded for flex according to the size of the boot. This means that small boots have the same relative flex as larger boots (other stiffening materials can make small boots too stiff and large ones too bendy). Many manufacturers vary the stiffness of the different insoles—the stiffest material is reserved for mountaineering boots, and the most flexible for what is usually described as “easy trail use” with a light load. You can judge flex by bending the boot: a stiff, hard-to-bend shoe is fine for kicking steps in snow but is tiring for most walking. A flexible shoe makes for easy hiking.

The lightest, most flexible shoes and boots may not have a lasting board at all. Instead, when the insole is removed, a line of stitching will be seen running round the edge of the sole or down the middle. This is known as sliplasting, in which the upper is sewn into a sock shape and then slipped onto the last. I prefer this construction for lightweight footwear, since it conforms to the natural shape of the foot and is very flexible. Sliplasted shoes are not usually as stiff as board-lasted ones, though there may be a flexible plate similar to a lasting board between the cushioning midsole and the outsole. Some shoes have combination lasting—the front is sliplasted, but there is a half-board in the heel. This gives a flexible forefoot but a more rigid heel.

The traditional sole stiffener is a half- or three-quarter-length steel shank, only half an inch or so wide, placed forward from the heel to give solidity to the rear of the foot as well as lateral stability and support to the arch while allowing the front of the foot to flex when walking. Full-length shanks are for rigid mountaineering boots, not for walking. Some boots combine a steel shank with a graded nylon insole.

Many boots incorporate a midsole of a shock-absorbing material. This is usually EVA in lightweight footwear and heavier but much harder-wearing polyurethane or microporous rubber in heavier boots. These midsoles are often tapered wedges, thickest under the heel. They absorb shock well, and I wouldn’t consider footwear without them—the difference they make in how your feet feel at the end of a long day is startling. They are designed to protect against the shock of heel strike—the impact when your heel hits the ground—which jars the knees and lower back as well as the feet. Cushioning also is needed at the ball of the foot, and the best shock-absorbing wedges are quite thick under the forefoot as well as the heel.

Some boots also have a stiffening and supportive synthetic plate under the cushioning midsole—this is a way to give some stiffness to a sliplasted shoe. Sometimes this plate—which is usually latticelike rather than solid—combines with the shock-absorbing midsole and the rand, cradling the foot and providing cushioning as well as good side-to-side support and stability. Even the heel counter and the toe box may be incorporated into these units.

This is the bit of the boot that determines whether you stay upright or skid all over the place. Once there were only a few outsole patterns, with the Vibram carbon-rubber Roccia and Montagna lug outsoles as the standard tread; now they are legion. Vibram has become a whole extended family of sole patterns in itself, and there are many others (Skywalk is one of the most common). Having tried a wide variety of these, I’ve concluded that any pattern of studs, bars, or other shapes seems to grip well on most terrain. The key is a pattern that bites into soft ground so that the shoe doesn’t slip and a sole made from soft enough rubber that when pressure is applied it grips rock and smooth surfaces by friction. I’ve had shoes with shiny outsoles that were just too hard to provide much friction; they were dangerous on wet pavement. Once the surface of the lugs had worn away, they gripped better. Note that no rubber sole, whatever the pattern or stickiness of the rubber, will grip on hard snow or ice. For that you need metal.

Some footwear uses the “sticky rubber” that revolutionized rock-climbing footwear. Soles with this material are ideal for scrambling and difficult rocky terrain, but the sticky, soft rubber that grips well on rock and other hard, fairly smooth surfaces doesn’t bite into soft ground so well. It’s also not very durable. Harder rubbers grip better on mud and wet vegetation and also last longer, so these are used for most boot soles. Some treads combine soft and hard rubber so that the edges grip well on soft ground while the center has good friction. Others are designed with different patterns and rubber densities for downhill braking and traction and uphill traction and push-off. I can’t say I can tell any difference between these and traditional soles, but they sound good.

The type of sole footwear has depends on its purpose. Soles with the deepest lugs are found on mountaineering boots, those with the shallowest on sandals and trail running shoes—though some sandals now have surprisingly deep lugs.

Boot heel designs. Rounded (left) and right-angled (right).

There has been some concern about the damage that heavily lugged soles do to soft ground, and some manufacturers have designed soles said to minimize this damage by not collecting debris in the tread. Studded soles seem to work best in this respect, but unless all your walking will be done on gentle trails, grip is the most important quality of outsoles. Grip should not be compromised, especially if you’re walking on steep, rugged terrain. Modern soles aren’t quite as damaging as traditional ones, since they tend not to have the 90-degree angles at the edges and heels that cut into the ground so deeply. Instead, the edges are rounded and canted.

Many soles are made from a dual-density rubber—a soft upper layer for shock absorption and a hard outer layer for durability—and combine grip with cushioning.

In stiff-soled boots you have to come down steep slopes on your heels, so square-cut heels are best. In flexible footwear you can put your feet flat on the ground so rounded heels are fine.

Heavier outsoles with deeper treads should outlast lighter soles, though it’s hard to predict tread life. Wear depends on the ground surface—pavement wears out soles fastest, followed by rocks and scree. On soft forest duff, soles last forever. I have found that on long walks, lightweight soles last 800 to 1,000 miles, while the traditional Vibram Montagna lasts at least 1,250 miles. However, soft EVA midsoles last only about 500 miles (polyurethane lasts longer), so the life of the sole depends on more than the wear of the lugs.

There is little controversy over outsole patterns, but the shape of the heel has generated heated discussions. Indeed, some designs have been blamed for fatal accidents. The debate is over the lack of a forward heel bar under the instep, together with a rounded heel (derived from running shoe outsoles) and how these features perform when descending steep slopes, especially wet, grassy ones. Traditional soles have a deep bar at the front of the heel and a right-angled rear edge, which their proponents say make descents safe. Rounded heel designs, they say, don’t allow you to dig in the back of the heel for grip or use the front bar to halt slips; instead, the sloping heel makes slipping more likely. To overcome these criticisms, some soles have deep serrations on the sloping heels and forward edges.

After experimenting with different outsoles and observing other hikers, I’ve concluded that it all depends on how you walk downhill. If you use the back or sides of the heel for support, you’re more likely to slip in a boot with a smooth, sloping heel than in one with a serrated or square-cut edge. If you descend as I do, however, with your feet flat on the ground, pointing downhill, and your weight over your feet, heel design is irrelevant. I’ve descended long, steep slopes covered with slippery vegetation in smooth, sloping-heel footwear without slipping or feeling insecure. I’ve noticed too that many people who slip while descending steep slopes keep their boots angled across the slope and descend using the edges of the sole, without much contact with the ground. For this a stiff boot with a right-angled heel works best. Of course, if you descend hills flat-footed, you need fairly flexible footwear.

Rounded heels are said to minimize heel strike, because they allow a gradual roll from the heel to the sole instead of the jarring impact when the edge of a square-cut heel hits the ground, but I haven’t noticed any difference in practice. A shock-absorbing midsole seems far more important for reducing heel-strike injury.

The most likely place for water to penetrate a boot is where the sole and the upper meet. Some boots have a rubber rand running around this joint, while others have just toe or toe and heel rands, or bumpers. Rands seal the joint against water and also protect the lower edge of the uppers from scuffs and scratches.

Joining the soles to the uppers is a critical part of footwear manufacture. If that connection fails, the shoe or boot will fall apart. Stitching used to be the only way of holding footwear together but is now used mainly in leather boots made for mountaineering or Nordic ski touring rather than for walking. The most common stitched construction is the Norwegian welt, sometimes called stitchdown construction, in which the upper is turned out from the boot, then sewn to a leather midsole with two or three rows of stitching. These stitches are visible and exposed, but they can be protected by daubing them with sealant.

Currently, on most footwear the uppers are heat bonded (glued at high temperatures) or cemented to the sole. (Some are also Blake or Littleway stitched, which means the uppers are turned in and stitched to a midsole, to which the outsole is cemented.) Unlike the Norwegian welt, the quality of these construction methods cannot be checked. A bonded sole has failed me only once, many years ago. On that occasion, the sole started to peel away from the boot at the toe after only 250 miles. I was on a long trek and far from a repair shop, so I patched the boots with glue from my repair kit almost every night and nursed them through another 500 miles. I wouldn’t like to repeat the experience.

Because fit is so crucial, I’m reluctant to recommend any specific models. I’m often asked to do so, though, so here are some hints. Over the years I’ve happily worn footwear from Adidas, Asolo, Bite, Brasher, Five Ten, Garmont, Hi-Tec, Lowa, Merrell, Montrail, Nike ACG, Raichle, Rockport, Salomon, Scarpa, Teva, The North Face, Vasque, and Zamberlan. That’s a lot of boots, shoes, and sandals. Most of the specific models I’ve used are no longer available. Well-recommended brands I’ve never tried include Alico, Birkenstock, Boreal, Chaco, Danner, Dunham, Gronell, Kayland, La Sportiva, Limmer, Technica, and Timberland.

Of the footwear I’ve tried most recently and that therefore hadn’t disappeared when I wrote this, here are my current favorites, described as examples rather than recommendations. Remember: my ideal shoe might be your worst nightmare.

I’ve almost worn out a pair of Merrell Onos, which have a synthetic leather upper lined with stretchy neoprene and Spandex. They fasten with adjustable clip buckles. The rear section is stiffened at each side for support. The molded EVA foot-frame is soft and cushioning and shaped to support the foot. It has an antimicrobial treatment too, which works well, as I found after a sweaty nine-day hike. The tread is reasonably deep and made from sticky rubber. They weigh 27 ounces (all weights are for a pair of men’s size 9½). I’ve hiked many miles in these sandals and found them supportive and comfortable, with a good grip on just about any terrain. But the Onos have been supplanted in my affections by Teva Wraptor 2s, the first sandal I’ve tried that holds the foot in place as well as the best lightweight shoes and boots. This is achieved by an ingenious design, a strap that runs across the instep, through the sole, and then back across the instep, completely encircling the foot. Tightening this strap pulls the sandal around the arch, heel, and instep for a very secure fit. Combined with the soft, deep foot-shaped top sole, this strap also helps prevent over-pronation. The straps are padded nubuck, fastened at the forefoot, instep, and heel with Velcro. There’s a dual-density EVA midsole and a deep tread on the outsole. They weigh 2 pounds, slightly on the heavy side for sandals but worth it for the support they give. Most recently I’ve been wearing Bite X-Tracs, which have a thick polyurethane footbed that can be replaced with Superfeet or other stabilizing footbeds. These have leather uppers with neoprene linings, a cushioning midsole, and an arch shank, and they weigh 29 ounces (without footbeds). The sole is torsionally flexible and quite wide, and the tread isn’t very deep, so while they’re fine on good trails, these sandals aren’t that good on rough and steep terrain. Being able to fit Superfeet into sandals is a great idea, though, and I hope that sandals more suited to rough terrain will appear with this feature.

Bite sandal with Superfeet footbed fitted. The footbeds stabilize the feet and minimize overpronation.

For low-cut shoes I like the sliplasted Salomon XA Pros, which are quite light at 27 ounces yet stable and well cushioned. They look like standard running shoes rather than trail shoes. I first tried these on a short adventure race and was impressed that after three hours or so of running and cycling on rough, steep terrain in very hot weather, my feet felt fine. The shoes are made from mesh backed with thin foam (which makes them quick drying and very breathable, though not at all water resistant), with synthetic leather reinforcements. There’s a dual-density EVA midsole for shock absorption and an outsole made from three hardnesses of rubber. A synthetic plate between the midsole and the outsole gives lateral stiffness to the rear of the shoe while allowing the forefoot to flex easily. The laces are made of thin Kevlar with a cord lock at the top and speed-lacing hooks. One yank and they’re tight, no knots required. They can’t slip or come undone, either. The lower hooks are offset, so the shoes flex with the foot. I’d wear the XA Pros more often, except that in the weather for which they’re most appropriate, I tend to choose sandals.

I’ve also been impressed with the sliplasted Blaze Low from The North Face, a suede-fabric shoe with a molded EVA midsole and a plastic plate for torsional stiffness. The shoes breathe well and dry fast, but the mesh means they’re not very water resistant. The excellent tread has studs in the center, which help them grip on wet grass, and lugs round the edges. The cushioning is particularly good; thicker and softer than on most footwear. These shoes are excellent for long distances, and for hard terrain that pounds your feet. The heel counter is firm and the torsional stiffness means the shoes don’t twist sideways much on rough terrain. Soft forward flex makes them very comfortable. Lacing is with eyelets and webbing loops. They weigh 29 ounces.

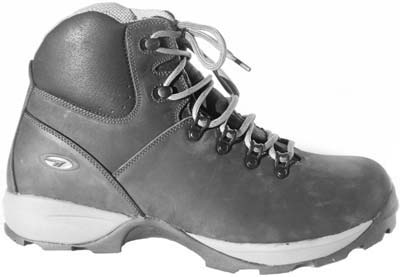

My favorite lightweight leather boot, the Hi-Tec Sierra V-Lite.

In theory, lightweight boots are my favorites, but I don’t seem to wear them much these days, preferring trail shoes or sandals when there’s no snow and slightly heavier boots when there is. Of the pairs I’ve tried in recent years, I like the Hi-Tec Sierra V-Lite Leather. These are made from nubuck leather with a synthetic CoolMax wicking lining. There’s a thermoplastic lasting board for torsional stiffness and an EVA midsole for good cushioning. Lacing is with four sets of tunnels and two sets of hooks. They weigh just 34 ounces, very light for leather boots. Heel to toe the boots are very flexible but on rough, steep terrain these boots give me good support due to the torsional stiffness. On one occasion I descended 3,000 feet off trail on frozen turf, rock, scree, tussocks, and wet grass with no problem. I was surprised at how good the water resistance was for such light boots. They do leak eventually but drying time is fast. Overall these feel more like trail shoes than heavier boots, with the addition of a high ankle.

Montrail’s 3-pound, 5-ounce Cristallo is a high-quality boot that does all that’s required without any bells and whistles. The Cristallo is made from nubuck with a synthetic lining. The boots have a graded nylon insole with a half-length steel shank, microporous rubber midsole, and Vibram outsole. Torsionally they are quite stiff because of the shank, but they flex well at the forefoot. They have a fairly low volume, like my feet. I did have to stretch them slightly at the toes, however. The 3-pound, 10-ounce Scarpa Delta M3 is a similar boot, again made from nubuck with a synthetic lining. The leather is treated with silicone and oil and has proved very water resistant. There’s a Vibram sole with an EVA shock-absorbing insert in the heel plus a polyurethane midsole. As with the Cristallos, I had to stretch them at the toes to get a good fit.

I wouldn’t choose either of these boots for trail hikes in summer. They’re too stiff, warm, and heavy. I wear them for mountain hiking when there’s snow and I think I may need to use crampons or for off-trail hiking in steep, rugged, rocky terrain where I want some protection for my feet.

This is my least favorite category; I rarely wear boots this stiff and heavy. But I have been pleasantly surprised by the relative comfort of Scarpa Mantas. These 4-pound, 6-ounce rigid-soled boots have a rocker sole, a rigid nylon midsole with a steel insert, polyurethane cushioning, speed lacing, and a well-fitting, padded upper that makes them quite bearable, though I wouldn’t want to do a long trail hike in them. However, if there’s much hard snow and ice around and crampons are needed most of the time, they’re my first choice. The uppers are made from rough-out water-resistant leather, and the sole is a deep-cleated Vibram M4 Tech with grooves at the toe and heel so clip crampons can be fitted. The polyurethane cushioning takes some of the sting out of rocks and hard surfaces, and the slight rocker in the sole makes walking on the flat easier than with a flat-soled boot. Although the ankles are held firmly in place, they can flex forward thanks to a cutaway section below the top two lace clips, which also makes walking on the flat relatively comfortable. The overall quality of the boots is superb.

A winter-weight boot (Garmont Pinnacle).

A midweight leather boot (Montrail Cristallo).

Although most footwear is fairly tough, it needs proper care to ensure a long life and good performance. This care can start before you wear the boots. Sealing any exposed stitching to protect it from abrasion will increase durability and make the seams waterproof. Urethane sealers like McNett Seam Grip work well, as do products specially designed for this use, like Aquaseal Stitch Guard. Some sealants come with an applicator; others are best applied with a syringe. Stitching should be sealed before you wear or wax the footwear so that the sealant has a clean, dry surface to stick to. I always used to seal the welts of my leather Nordic ski boots so that water didn’t wick in through the stitching when the boots flexed. My plastic telemark boots don’t have stitching, and I haven’t bothered sealing the seams of other footwear.

Muddy, dirty boots need washing; if mud dries on the uppers, especially if they’re leather, they can harden and crack. A soft brush (I use an old toothbrush) helps remove mud from seams, stitching, and tongue gussets, though you should be careful not to scratch leather. I find cold tap water adequate for cleaning hiking footwear, and I don’t use soap. I’m not bothered if footwear is stained or discolored; indeed, this can add character. But if ingrained dirt is particularly stubborn or you want to remove any stains, there are specific cleaning products—Nikwax Cleaning Gel, Granger’s New Technology Footwear Cleaner, and Aquaseal All Purpose Footwear Cleaner. The first two have easy-to-use sponge applicators. You just rub them over the boots, then rinse off the foam, scrubbing with a soft nylon brush if necessary. A sink is the best place to do this.

The insides of boots can get dirty too, making them smelly and less breathable, so sweaty socks are more likely. In boots with waterproof membranes, tiny specks of grit may work their way through the lining and cut the membrane so it leaks. Just a wipe with a clean, damp cloth may be enough cleaning—it’s all I ever do. However, Nikwax suggests filling boots with water and leaving them to soak overnight before emptying them out and rinsing them.

Water-based footwear products are easy to apply and produce no pollution, since they contain no solvents.