CLOTHING IS A LITTLE MATTER. THE TRICK IS TO WEAR AS LITTLE AS POSSIBLE WITHOUT BECOMING EVEN A FRACTION TOO HOT OR TOO COLD.

—Journey Through Britain, John Hillaby

When the clouds roll in, the wind picks up, and the first raindrops fall, your clothing should protect you from the storm. If it doesn’t, you may have to make camp early, crawling soggily into your tent and staying there until the skies clear. At the worst, you could find yourself in danger from hypothermia. Besides keeping you warm when it’s cold and dry when it’s wet, clothing should also keep you cool when the sun shines. In other words, clothing should keep you comfortable regardless of the weather. Choosing lightweight, low-bulk clothing that does all this requires care. Before looking at clothing in detail, I’ll try to give some understanding of how the body works when exercising and what bearing this has on clothes.

The human body evolved to deal with a tropical climate, and it ceases to function if its temperature falls more than a couple of degrees below 98.4°F (37°C) or rises more than a couple of degrees above that. In cool climates, the body needs a covering to maintain that temperature, because the heat it produces is lost to the cooler air. Ideally, clothing should allow a balance between heat loss and heat production, so that we feel neither hot nor cold. It’s hard to maintain this balance when we alternate sitting still with varying degrees of activity in a range of air temperatures and conditions: when we’re active, the body pumps out heat and moisture, which has to be dispersed; when we’re stationary, it stops doing so.

Hiking in a synthetic-insulated top, fleece-lined cap, and gloves on a cold, windy fall day in the North Cascades.

The body loses heat in four ways, which determine how clothing has to function to keep its temperature in equilibrium:

Convection, the transfer of heat from the body to the air, is the major cause of heat loss. It occurs whenever the air is cooler than the body, which is most of the time. The rate of heat loss increases in proportion to air motion—once air begins to move over the skin (and through your clothing), it can whip body warmth away at an amazing rate. To prevent this, clothing must cut out the flow of air over the skin; that is, it must be windproof.

Convection, the transfer of heat from the body to the air, is the major cause of heat loss. It occurs whenever the air is cooler than the body, which is most of the time. The rate of heat loss increases in proportion to air motion—once air begins to move over the skin (and through your clothing), it can whip body warmth away at an amazing rate. To prevent this, clothing must cut out the flow of air over the skin; that is, it must be windproof.

Conduction is the transfer of heat from one surface to another. All materials conduct heat, some better than others. Air conducts heat poorly, so the best protection against conductive heat loss is clothing that traps and holds air in its fibers. Indeed, the trapped air is what keeps you warm; the fabrics just hold it in place. Water, however, is a good heat conductor, so if your clothing is wet, you will cool down rapidly. This means that clothing has to keep out rain and snow, which isn’t difficult—the problem is that clothing must also transmit perspiration to the outer air to keep you dry, known as breathability, or moisture vapor transmission (MVT).

Conduction is the transfer of heat from one surface to another. All materials conduct heat, some better than others. Air conducts heat poorly, so the best protection against conductive heat loss is clothing that traps and holds air in its fibers. Indeed, the trapped air is what keeps you warm; the fabrics just hold it in place. Water, however, is a good heat conductor, so if your clothing is wet, you will cool down rapidly. This means that clothing has to keep out rain and snow, which isn’t difficult—the problem is that clothing must also transmit perspiration to the outer air to keep you dry, known as breathability, or moisture vapor transmission (MVT).

Evaporation occurs when body moisture is transformed into vapor—a process that requires heat. During vigorous exercise, the body can perspire as much as a quart of liquid an hour. Clothing must transport it away quickly so that it doesn’t use up body heat. Wearing garments that can be ventilated easily, especially at the neck, is important, as is wearing breathable materials that water vapor can pass through.

Evaporation occurs when body moisture is transformed into vapor—a process that requires heat. During vigorous exercise, the body can perspire as much as a quart of liquid an hour. Clothing must transport it away quickly so that it doesn’t use up body heat. Wearing garments that can be ventilated easily, especially at the neck, is important, as is wearing breathable materials that water vapor can pass through.

Radiation is the passing of heat directly between two objects without warming the intervening space. This is the way the sun heats the earth (and us on hot, clear days). Radiation requires a direct pathway, so wearing clothes—especially clothing that is tightly woven and smooth-surfaced—mostly blocks it. Very little heat is lost by radiation anyway. Reflective radiant barriers built into clothing really don’t make any difference.

Radiation is the passing of heat directly between two objects without warming the intervening space. This is the way the sun heats the earth (and us on hot, clear days). Radiation requires a direct pathway, so wearing clothes—especially clothing that is tightly woven and smooth-surfaced—mostly blocks it. Very little heat is lost by radiation anyway. Reflective radiant barriers built into clothing really don’t make any difference.

As if keeping out rain, expelling sweat, trapping heat, and preventing the body from overheating weren’t enough, clothing for walkers must also be light, durable, low in bulk, quick drying, easy to care for, and able to cope with a wide variety of weather conditions. The usual solution is to wear several light layers of clothing on the torso (legs require less protection), which can be adjusted to suit weather conditions and activity. The layer system is versatile and efficient if used properly, which means constantly opening and closing zippers and fastenings and removing or adding layers. In severe conditions I also use layers on my legs, hands, and head in severre conditions.

A simple layering system consists of an inner layer of thin wicking material that removes moisture from the skin, a thicker midlayer to trap air and provide insulation, and a waterproof-breathable outer shell to keep out wind and rain while allowing perspiration to pass through. This neat three-layer system won’t cope with a wide range of conditions, however. Additional layers could include one or two more midlayers such as a wind shell or soft shell and a thick, insulated garment for camp and rest stops in cold weather. I often carry six layers—a thin base layer, two thin midlayers, wind shell, rain shell, and insulated top (see the trip sidebars in Chapter 2 for lists of clothing I’ve carried on actual trips). Several thin layers are more versatile than one thick one, which is either on or off, often leaving you either too hot or too cold. The boundaries of the different layers have always been a little fuzzy—thick inner layers can be used as midlayers, and windproof midlayers are also outer shells when it’s not raining—and this is getting fuzzier with garments claimed to function as all three layers. But nothing beats the versatility of having separate garments that you can combine differently according to the conditions.

Dressed for cold, stormy weather in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. Warm, waterproof hat, fleece-lined waterproof gloves, and waterproof-breathable shell jacket over windproof jacket and lightweight fleece top.

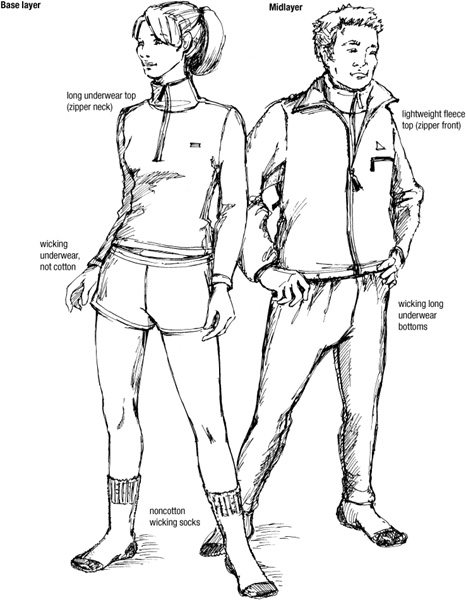

A base-layer top may be adequate on its own in warm weather. Add a thin fleece when the temperature drops. Wicking long underwear can be worn under trail pants in cold weather.

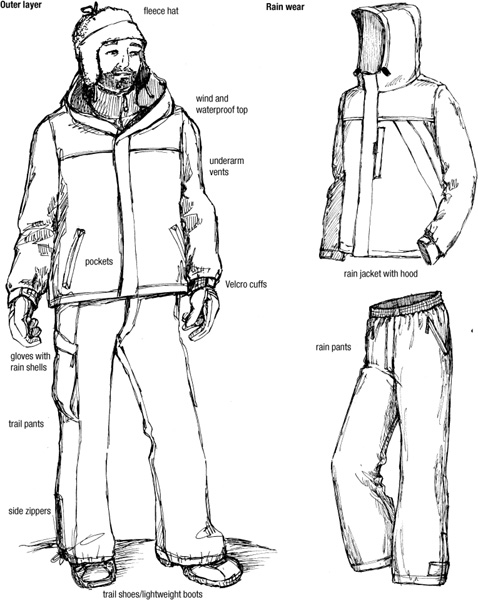

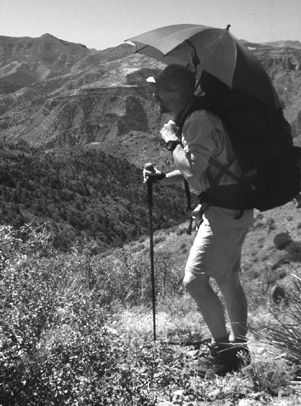

Clothing for wet, windy weather.

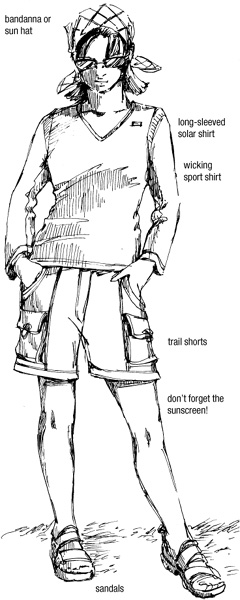

Hot-weather wear.

How much clothing you plan to take on a particular hike depends on the conditions you expect. I take enough to keep me comfortable in the worst likely weather. If I’m in doubt as to what is enough, I sometimes take a light insulated vest just in case.

I don’t carry clothing that can’t all be worn together if necessary. If it’s cold, I want to be able to wear everything. The only spare items I carry are underpants and socks.

Although it’s sometimes described as “thermal” underwear, the main purpose of the inner layer (also known as the next-to-skin or base layer) is to keep the skin dry rather than warm—often called moisture management. If perspiration is removed quickly from the skin’s surface, your outer layers keep you warm more easily. If the layer of clothing next to your skin becomes saturated and dries slowly, your other clothes, however good, have a hard time keeping you warm. No fabric, whatever the claims made for it, is warm when wet.

While you’re on the move, as long as your outer layer keeps out rain and wind and your midlayer provides enough warmth, you generate heat and stay warm even if your inner layer is damp. But once you stop, wet undergarments will chill you rapidly, especially if you’ve been exercising hard and producing a great deal of moisture. After a climb to a pass or a summit, you often want to stop, both for a rest and to enjoy the view you’ve worked so hard to reach. Once you stop, however, your heat output drops rapidly, just when you need that heat to dry out your damp base layer. But that damp base layer conducts heat away from the body, producing after-exercise chill. The wetter and slower drying your clothing, the longer such chill lasts and the colder and more uncomfortable you’ll be. Thus the inner and outer layers are important because they can minimize after-exercise chill by wicking moisture away from the skin and stopping rain from soaking your clothing; what goes on between these layers matters less, and this is where compromises can be made.

The one inner material to avoid is cotton, since it absorbs moisture quickly and in great quantities. It also takes a long time to dry, using up a massive amount of body heat. To make matters worse, damp cotton clings to the skin, preventing a layer of insulating air from forming. I haven’t worn cotton next to my skin for years—not even on trips in sunny weather when some people like light cotton or cotton-blend garments because they’re cooling when damp. I find thin synthetics or wool more comfortable than cotton in the heat, and I don’t need to change my top if the weather turns damp or cold.

Base-layer fabrics remove body moisture by transporting or wicking it away from the skin. Synthetic fibers are hydrophobic—they repel moisture—and tend to wick quickly. Natural fibers like wool and silk are hydrophilic—water loving—and absorb moisture into their fibers before passing it more slowly to the outside.

Synthetics can wick moisture by being nonabsorbent and having an open weave through which the moisture quickly passes, and having hydrophilic (water-attracting) outer surfaces that “pull” moisture through the fabric and away from the skin. In both cases, body heat pushes the moisture through the fabric.

Although synthetic wicking fabrics are very good, they can become overloaded with sweat and end up very damp on the inside. An important factor is the time they take to dry when you’re not producing enough body heat to push the moisture through the fabric. The best are those with brushed or raised fluffy inner surfaces that have a minimum of material in contact with the skin, letting it dry quickly. If the inner surface is smooth and tightly woven, moisture passes through it more slowly. Oddly, both tightly woven and open-weave outer surfaces can speed moisture movement. In the first case moisture can spread out over the surface of the fabric and evaporate or pass into the next layer; in the second case the open weave allows moisture to pass through very quickly. Fabrics with different materials on the inside and outside are known as bicomponent fabrics. Examples include Polartec Power Stretch, Polartec Power Dry, and Páramo Parameta S.

Most fabrics come in several weights. The lightest—sometimes called silkweight—are very thin and fast wicking, ideal for aerobic pursuits such as trail running but also good for backpacking, either on their own in the heat or under other layers in cold weather. Midweight underwear is slightly heavier and thicker and usually has a tighter weave. It’s warmer but often wicks more slowly, which is fine in cool weather. The heaviest and thickest fabrics are labeled expedition or winter weight. Most of these don’t wick moisture or dry as fast as the lighter fabrics and are better suited for midlayers. A few, like Power Stretch and Parameta S, wick as well as or better than thin fabrics.

Designs are usually simple; most tops come with either a crewneck or a turtleneck with a zipper, buttons, or snaps at the neck. You can get short or long sleeves; I prefer short-sleeved crewneck T-shirts for warm weather and long-sleeved zippered turtlenecks for colder weather. The latter are good as midlayers too. Close-fitting garments are much more efficient than baggy ones. My partner, hiker Denise Thorn, says she didn’t realize how effective base layers could be until she wore women’s styles that fitted properly rather than loose “unisex” tops. Most makers now offer women’s and men’s base layers, while some companies like Wild Roses (now called OR Women) and Isis make only women’s clothing. There are also bras made from wicking fabrics.

Figure-hugging “tights” are the norm for long underpants. Underpants made from wicking synthetics are far superior to cotton. Close-fitting garments help trap air and wick moisture quickly and also fit easily under other garments. Long pants should have a particularly snug fit to avoid the discomfort of baggy long johns sagging down inside other layers; elasticized waists are essential. Long backs stop tops from riding up at the waist. Stretchy fabrics often wick fastest because of their close fit. They’re generally more comfortable, too. Seams should be flat sewn to avoid rubbing and abrasion. Dark colors show dirt and stains less, but white or pale colors reflect heat better when worn alone in warm weather.

Choosing a wicking synthetic fabric can seem hard because there are so many, each with a fancy name and claiming to work better than the others. Actually there are only a few base fabrics, and they’re all derived from petrochemicals. Polypropylene was the original fiber used, but most base layers are now made from polyester. Other fibers like chlorofiber, acrylic, and nylon have just about disappeared.

Synthetic base layers are notorious for smelling bad, sometimes after only brief use. Ironically, the hydrophobic properties that make them effective at wicking moisture are the main reason for this. Your body moisture contains oils that stick to the fabric as the liquid evaporates or moves into your next clothing layer. These oils attract bacteria and can also undergo oxidation, both leading to nasty smells. Like the fabric, the oils are hydrophobic. Washing in cool water doesn’t remove them. Hot water does, but not all fabrics can be washed in hot water without shrinking, making it hard to get the smell out. Hanging clothes in the sun and wind can help, as can repeated washing in plenty of detergent and soaking in cold water with a little dissolved soap. It’s best, though, to choose garments that can be washed and dried at hot temperatures. This is also useful for long hikes when you want to chuck all your dirty clothes into a washer and dryer at town stops without worrying about the temperature.

Many fabrics have antimicrobial treatments. Most work a little but don’t stop garments from smelling for very long. Fibers such as X-Static that contain silver—a natural antimicrobial that contains no chemicals and is safe next to the skin—work best. Odor Resistant Polartec Power Dry contains silver fibers. Silver can’t wear out or be washed out, so it lasts the life of the garment. It’s said to remove 99 percent of bacteria in an hour and to work best in warm, humid environments. To test this, I wore an X-Static top for chopping firewood, day hikes, and cycle rides as well as backpacking trips. After two weeks’ wear, my unwashed top smelled faintly musty, but nothing worse. My family didn’t tell me to change it and take a shower. Synthetics incorporating silver fibers seem to be the answer to stinky synthetic underwear.

POLYPROPYLENE “Polypro” is the lightest and thinnest wicking synthetic. Introduced by Helly Hansen in its Lifa line back in the 1970s, it dominated the market for a while but is now found mostly in budget garments. Polypro won’t absorb moisture but quickly passes it along its fibers and into the air or the next layer. It wicks away sweat and dries so fast that after-exercise chill is negligible. However, it’s the worst synthetic fabric for stinking, producing a stench that can be hard to get rid of. Apart from the odor, if you don’t wash it at least every couple of days, polypro ceases to wick properly, leaving your skin clammy and cold. On long trips you have to carry several garments or rinse one out regularly and learn to live with the smell of stale sweat.

Polypro’s drawbacks are mostly overcome in Helly Hansen’s Lifa range. Helly’s polypro has a softer, less “plastic” feel than standard polypro, and it can be washed at 140°F (60°C), a heat that rids it of the noxious aroma. It’s also said to be resistant to the bacteria that cause smells. Lifa polypro comes in three types: thin, stretchy Lifa Sport; midweight Lifa Active; and Prowool, which has an outer layer of merino wool. I’ve worn a Lifa Sport crewneck top for several days without washing it, and though it smells faintly musty, I can bear to have it in the tent, something I wouldn’t do with the old polypro after even one day’s wear. It wicks moisture efficiently and, I suspect, faster than standard polypro. My crewneck Lifa Sport top weighs 5 ounces; my bottoms, which I mostly carry for campwear or unexpected cold weather, weigh 3.75 ounces.

POLYESTER Polyester repels water but has a low wicking ability—not ideal for underwear, since sweat just stays on the skin. However, it can be treated with chemicals or mechanically altered so that it becomes hydrophilic, resulting in moisture being drawn through the material to the outer surface, where it spreads out and quickly dries. The drawback is that after repeated washings chemical treatments wear off, though this isn’t the problem it once was. When this happens the material stops wicking.

There are many wicking polyester fabrics. Some are proprietary like Patagonia’s Capilene, GoLite’s C-Thru, REI’s MTS, and Lowe Alpine’s DryFlow. Others, like Polartec Power Dry, CoolMax, Thermolite Base, and Akwatek, are used by many companies, though they may appear under names like Marmot’s DriClime, which is Power Dry. Over the years I’ve tried many polyester base layers and concluded that they all work pretty well and there’s not much difference between them.

Of the expedition-weight polyester fabrics I’ve used, two stand out. Polartec Power Stretch and Páramo Parameta S both wick moisture faster than any other materials of similar weight and better than many lighter-weight fabrics. Both materials have soft, brushed inner surfaces that wick moisture rapidly and smooth, tightly woven outers that spread the moisture so it evaporates quickly. Power Stretch is used by many companies; my zip-neck top and tights are made by Lowe Alpine and weigh 10 and 7 ounces, respectively—less than some expedition-weight fabrics that aren’t as warm or as efficient at removing moisture. As the name suggests, the fabric is very stretchy and hugs the body. Parameta S doesn’t stretch and is exclusive to Páramo. I have the Trail Shirt, a conventional design with a collar, two chest pockets, and a snap-fastened front. It weighs 14 ounces. All Parameta S and some Power Stretch garments (such as Mountain Hardwear’s Zip T) can be reversed so the smooth side is on the inside. This is meant to make them cooler and thus increase the temperature range over which the garment is comfortable. It works to some extent, but I still find the Trail Shirt a bit warm in hot weather. I’ve had my Power Stretch and Parameta S garments for many years, and they’ve proved very durable. I now mostly wear them as midlayers.

Weights for base-layer tops and bottoms range from 3 ounces in light garments to 14 ounces for expedition-weight ones. Briefs start at about 2 ounces.

WOOL Wool, the traditional material for outdoor underwear, has had a remarkable revival and is now regarded by many as the best choice for base layers. I tend to agree. Though it might seem that wool wouldn’t fit into a layering system with high-tech synthetics, it does. Wool is excellent at drawing moisture into its fibers and leaving a dry surface against the skin. It can absorb up to 30 percent of its weight before it feels wet and cold, so after-exercise chill is not usually a problem. I’ve worn wool next to my skin on many winter ski tours and have always felt warm, even in camp after an energetic day. On those tours I’ve also worn the same top for two weeks with no odor problem. Because wool is hydrophilic and absorbent, body oils go into the fibers rather than staying on the surface and attracting the bacteria that cause smells. Wool’s limitations used to be its warmth, which made it useful only for cold weather, and the need for careful washing, often by hand. Now, however, there are very fine tops that work well in the heat and that can be machine-washed without shrinking. Wool does stretch slightly, though it usually regains its shape when washed. It is pretty durable, too.

What puts many people off wool is its reputation for being itchy. Old-style wool with coarse fibers could irritate the skin, though fine knits have always been available. When I began backpacking I wore a thin lambswool sweater I bought from a department store as my base layer in cold weather. I don’t remember it’s being itchy. The best wool base layers are made from fine, soft merino wool, which feels luxurious next to the skin, far more comfortable than any synthetic I’ve ever worn. SmartWool began the return to wool with its merino garments. Many others have followed as people learn just how wonderful wool is to wear, but of the garments I’ve tried, SmartWool still has the edge on softness and comfort. As a final plus, wool is a good material to wear around fires, since it doesn’t burn easily or melt like synthetics, making it much safer and less liable to be damaged by sparks.

Wool is also relatively light; I have an Icebreaker long-sleeved crewneck merino wool top that weighs 7 ounces and a SmartWool Aero short-sleeved merino wool T-shirt that weighs 6 ounces, only a little more than equivalent synthetic ones. Both are light and cool enough for warm weather. Thicker, warmer garments weigh more, of course. My SmartWool Traditional Long Sleeve Crew and Traditional Relaxed Tights weigh 12 ounces and 9 ounces, respectively. These are warm garments, however. I wear them only when I expect temperatures to be below freezing. The top makes a good midlayer. Terramar has some good merino wool base layers, too. Its long-sleeved crew weighs 10.5 ounces. Terramar also makes polyester-wool mix and polyester-wool-Outlast acrylic garments (for my opinion on Outlast, see page 75). Wool-synthetic garments work quite well in my experience, though they’re not quite as comfortable as pure wool. Ibex also has a good reputation for its wool base layers (and other wool clothing), though I haven’t tried any of it, and Arc’teryx has a new line of merino wool base layers.

SILK Silk is the other natural material used in outdoor underwear. Like wool, it can absorb up to 30 percent of its own weight before it feels damp. Silk’s best attribute, however, is its luxurious texture; it’s light, too—a long-sleeved top weighs 3 to 4 ounces. A silk top I wore on a two-week hike in damp, cool weather kept me warm and dry, and at the end the odor was negligible. It was badly stained with sweat and dirt, though. When I rested after strenuous exercise, the top felt clammy for a few minutes, but then it warmed up. I probably won’t take silk on a long hike again, though, because it demands special care; it has to be hand washed and dried flat, and it won’t dry overnight in camp unless the air is very warm. Among those offering silk garments are Terramar, SilkSkins, and REI.

Cotton or cotton-synthetic shirts have always been popular for warm weather, though I find a light wool or synthetic top better because it gets less clammy and dries more quickly. And if the weather turns cold or wet, a noncotton top doesn’t get cold and uncomfortable under other layers.

However, there are now a large number of synthetic shirts designed specifically for hiking in warm weather. Most are traditional in style, with collars, snap or button closures, and breast pockets. The fabrics feel nice against the skin, wick a little, though not as well as wicking base layers, and dry quickly. A loose fit is more comfortable than a close one, since it allows moisture to disperse and cool air to move inside the shirt. Unlike most base layers, these shirts resist light winds. I now wear one on any trip where I expect it to be sunny and warm much of the time. I particularly like shirts with large pockets, in which I carry maps, a notebook and pens, binoculars, a whistle, a compass, and other items. Long sleeves are more versatile: roll them up in the heat, roll them down when it’s cool or you want to keep the sun off your arms. Most shirts have buttoned tabs to keep the sleeves from falling down when rolled up. If the weather is a little too chilly for the shirt alone, I wear it over a base layer.

My favorite is the Mountain Hardwear Canyon, which is made from soft Supplex nylon and has one zipped pocket and one vertical Velcro-closed pocket. There are mesh ventilation panels under the arms and down the sides plus mesh across the back and stretch panels in the shoulders, though I can’t say the shoulder panels make much difference. The collar has an extra panel at the back, so when turned up it really protects your neck from the sun. The Canyon weighs 10 ounces. As shirts go it’s expensive, but it has proved durable, though it’s somewhat stained from sweat and dye that has leached out of pack harnesses. You could of course just wear a nylon or polyester casual shirt, as a few people I know do. These are much less expensive and don’t have all the features, but they seem to work well in the heat, though they can get a little sweaty.

A shirt I’ve had for many years that does better duty than most shirts of this type as a base layer in the cold and wet is Sequel’s Solar Shirt, which has a wicking mesh body and, in current models, a nylon-polyester-cotton mix yoke. My original version has a CoolMax yoke, and I do wonder if the new mix will wick quite as well. The big advantage, though, is that it’s a firmer fabric, so there’s a stand-up collar and two breast pockets that look as though they’d be more comfortable with stuff in them than the soft mesh ones on my version. The Solar Shirt is a pullover design with a deep front opening. Mine is the long-sleeved version and weighs 8 ounces; current models are listed as 9.6 ounces. I first wore my shirt for a two-week hike in the Grand Canyon and found it superb in the heat; it never felt sticky or clammy, and it dried very quickly. At the end of this late-fall trip, the weather turned cold and windy, with frequent rain and hail; despite its accumulation of ten days’ sweat, dust, and sunscreen, the Solar Shirt performed well as a base layer under a microfleece top and light rain jacket.

An unusual development is W. L. Gore’s Wind-stopper N2S fabric. The N2S stands for “next to skin,” yet this is a windproof fabric, since it contains a Windstopper membrane. Gore says that N2S can function as a wicking base layer, a light insulating layer, and a windproof and showerproof shell. The membrane is sandwiched between two thin, soft layers, and garments feel flexible and comfortable. I’ve tried two garments, the Mountain Hardwear Transition (11 ounces) and the Marmot Evolution (11.5 ounces), both pullover designs with high collars and deep front zippers. (A lighter one is the GoLite Stealth Wind Shirt, at 9 ounces.) However, the Evolution has Power Stretch panels down the sides, while the Transition is 100 percent N2S. Both garments are stretchy, comfortable to wear, and windproof, and they wick moisture well. But I found they are comfortable on their own only over a narrow temperature range. If it’s above 50°F (10°C), I am too warm and start to feel sweaty unless there’s a very strong wind. If it’s below 40°F (5°C), I start feeling chilly unless it’s calm. This is not very versatile. The garments also smell a fair bit after a day’s wear—I hate to think what they’d be like after a week. Once I’d discovered the performance limits for me, I started wearing the N2S tops as midlayers and found them far more functional and far less smelly. I think keeping the windproof and base layers separate is more practical, but if you want windproof underwear, it does exist.

The midlayer keeps you warm by trapping air in its fibers. It also has to deal with body moisture that has passed through the inner layer, so it needs to let that moisture through or else absorb it without losing much warmth. Some midlayer garments are windproof and will resist a fair degree of rain, but they’re not a substitute for a rain jacket in a real downpour.

Midlayer clothing can be divided into two types: trailwear and rest wear or campwear. The first category includes wool tops, light- and medium-weight fleece, soft shells, and wind shells. In warm weather, one or two of these garments may be all you need for campwear as well. Mostly though, I carry a down- or synthetic-filled top or a thick fleece top to keep me warm when stationary. Of course you can wear these while hiking if necessary.

Midlayers come in every imaginable style of shirts, sweaters, smocks, vests, and jackets. Garments that open down the front at least partway are easier to ventilate than polo or crewneck styles—and ventilation is the best way to get rid of excess heat and prevent clothing from becoming damp with sweat. Far more water vapor can escape through an open neck than can wick through the fabric. Conversely, high collars keep your neck warm and hold in heat. I used to avoid pullover designs for fear I’d overheat, but as long as I can open up the top 8 or 10 inches, I’ve found I can cool off when necessary. Pullovers tend to weigh less than jacket styles, so I now use them regularly.

The traditional midlayer fabrics are wool and cotton, though they aren’t so popular anymore. With cotton, this is for good reasons: it’s heavy for the warmth provided, soaks up moisture, and is slow to dry. Many years ago I wore a thick brushed cotton (chamois) shirt on a two-week hike to remind myself how cotton shirts perform. Worn over a silk inner layer, it was comfortable and warm; worn under a waterproof-breathable shell, it never became more than slightly damp, despite wet and windy weather. I suspect that this was partly because the silk inner layer took up much of my sweat and the cotton shirt might have become damper with a synthetic inner layer. The performance then was OK, but the shirt weighed 17.5 ounces, more than twice the weight of a fleece top of equivalent warmth, and was bulky when packed. I’ve never hiked in a heavy cotton shirt since. I hadn’t worn wool in many years either, not since discovering fleece more than two decades ago, but recently I have used the 12-ounce SmartWool Traditional Crew as a sweater and found that it works very well, though it’s heavier than fleece of equal warmth. SmartWool and Ibex both make wool sweaters, cardigans, jackets, and vests that look good and should be functional alternatives to synthetic garments. And of course if you have some wool sweaters in your closet, they should do fine. The traditional wool shirt in check, plaid, or tartan is still around too, from traditional companies like Woolrich and Pendleton. I have an ancient one I used to hike in back in the 1970s. It weighs 15 ounces, which makes it heavy for the warmth compared with fleece.

Cotton and wool shirts and sweaters mostly disappeared from the backcountry with the advent of fleece, for many years now the standard fabric for warm garments. Fleece insulates well, moves moisture quickly, and is light, hardwearing, almost non-absorbent, and quick drying. These properties make fleece ideal for outdoor clothing. Most fleece is made from polyester, though you may find nylon, polypropylene, and acrylic versions.

Fleece, or pile as it used to be called, was first used in clothing by Helly Hansen and tested in Norway’s wet, cold climate, for which it proved ideal. In North America it became popular after Malden Mills made a smoother version called Polarfleece for Patagonia in 1979. In 1983 this was replaced by the first of the Polartec fleeces, introduced by Patagonia as Synchilla, and the takeover of outdoor warm clothing by fleece was under way. There are other manufacturers of fleece, including Dyersburg and Draper, but in my opinion Malden Mills still leads the way.

Fleece isn’t just one fabric, of course; it comes in a wide variety of weights and finishes. The more loosely knit, thicker, furrier fabrics are sometimes called pile; fleece is often reserved for denser fabrics with a smoother finish. But makers use both terms for the same fabrics, so they are in effect interchangeable. Malden Mills grades its classic Polartec fleece fabrics as 100, 200, and 300 weight, and other makers have similar weights. The higher the number, the warmer and thicker the fleece. Not all fleece fits easily into this system, but it is a useful guide.

Worn over a wicking inner layer and under a waterproof-breathable shell, fleece can keep you warm in just about any weather while you are on the move and is particularly effective in wet, cold conditions. Fleece moves moisture quickly: at the end of a wet, windy day, I’ve often found that the outside of my fleece top is damp from condensation inside my rain jacket but the inside is dry. If you feel cold, nothing will warm you up as fast as a dry, fluffy fleece top next to your skin.

Of course, fleece has drawbacks, albeit minor ones. It’s not windproof—you can easily blow through it—which means you need a windproof layer over it even in a cool breeze. Although this is a disadvantage at times, the lack of wind resistance means that garments are very breathable and comfortable over a wide temperature range—without a shell when it’s warm or calm, with one when it’s cold or windy. There is windproof fleece clothing (see pages 143–44), but it’s heavier, bulkier, and less breathable than ordinary fleece. Another drawback is that fleece clothing doesn’t compress well, so it takes up more room in the pack.

Fleece garments should be fairly close-fitting to trap warm air efficiently. They are prone to the bellows effect—cold air is sucked in at the bottom of the garment, replacing warm air—so the hem should be elasticized, have a drawcord, or be designed to tuck into your pants. Cuffs and collars keep warmth in best if they fit closely. A high collar helps keep your neck warm and stops warm air from escaping.

Most fleece garments are hip length, which is just about right to keep them from riding up under your pack hipbelt. Pockets are useful, especially hand-warmer pockets, for around camp and at rest stops, but they are not essential. Hoods can be nice in cold weather, though they’re not found on many garments. In light fleece I like pullover tops with zippers or snaps at the neck. Fancier designs simply add more weight.

I wear fleece garments most days, since I live in a mostly damp and cool rural area in the hills and I’m outdoors almost every day. I don’t like over-heated houses, so I wear fleece indoors much of the year too. Over the years I’ve accumulated a whole wardrobe of fleece garments, from old Helly Hansen nylon-fiber pile ones—now relegated to outdoor tasks like gathering wood—and early Patagonia Synchilla Snap Ts and Retro Cardigans to much newer Polartec Windbloc and Gore Windstopper jackets. Though fine for day-to-day wear, most are not versatile enough for backpacking; they are too warm when I’m walking and bulkier than alternatives for carrying. However, for hiking in cool weather and for campwear in warm weather, I find the lightest 100-weight fleece provides all the insulation I need. Sometimes called microfleece, this material is comfortable, soft, dense, nonstretchy, and thin. It can be worn next to the skin, though it doesn’t wick very well. However it’s excellent as a midlayer. When worn over a Power Stretch base layer, it’s all the insulation I need while hiking in freezing weather. Garment weights run from 8 to 16 ounces. I’ve had several 100-weight fleece tops over the years, and they’ve all worn well. My favorites are two pullover designs with short neck zippers. One is a Lowe Alpine Polartec 100 top that weighs 11 ounces and has a small breast pocket. The other is a Jack Wolfskin Gecko, made from the company’s own Nanuc microfleece. This is my most used fleece because it weighs just 8 ounces. Just about every maker of fleece garments has a thin microfleece top in its range, and there are plenty of choices. It takes up little room in the pack, so I carry a light fleece year-round. Expedition-weight base layers give similar warmth and make good alternatives. Besides the Power Stretch and Parameta S tops described earlier, I have a Patagonia R1 Flash Pullover, made from a thick version of Polartec Power Dry with a smooth outer face and raised fleece pillars on the inside that trap warm air and aid wicking. It weighs 12 ounces and is more comfortable next to the skin than microfleece because it wicks well. Another alternative for windy weather is one of the Gore Windstopper N2S base layers described previously.

I used to consider midweight 200-weight fleece the most versatile, wearing it as campwear on cool summer evenings and as a midlayer while on the move in very cold weather. I rarely use it anymore, however; it’s been squeezed out by better alternatives. If I want warmth when hiking I prefer to wear two lighter fleeces or, if it’s really cold, a light top filled with synthetic insulation, while for camp I prefer something warmer than midweight fleece. There are plenty of midweight fleece tops, in weights from 12 to 25 ounces, with Polartec 200 being the standard fabric.

The warmest fleece, like Polartec 300, is too warm to wear while hiking except in extreme cold unless you feel the cold a great deal. It’s useful as a warm layer when you’re resting and in camp, especially in wet, cold weather. Most of these fabrics are quite heavy and bulky, though. There is one exception, 6.5-ounce high-loft Polartec Thermal Pro, a shaggy, furlike fleece that is very warm for the weight. It has an open weave and is very breathable and fast drying, though it has no wind resistance at all. It’s also very soft and flexible and feels wonderful next to the skin. Indeed, it feels so nice and looks so soft that people often come up and stroke it—which may or may not appeal to you. Patagonia uses it in its Regulator R2 garments. I have an R2 jacket that weighs 14.5 ounces. It has Power Stretch side panels, a full-length front zipper, and two zippered hand-warmer pockets. Other companies making 6.5-ounce Thermal Pro garments include Cloudveil, Mountain Hardwear, Marmot, Lowe Alpine, and Arc’teryx.

There are other types of Thermal Pro that are heavier, warmer, and less fluffy, such as the 9.5-ounce fabric used in Patagonia’s 20-ounce R3 Radiant Jacket (which I’m wearing as I write this), but I think the R2 version is the best for backpacking. Thermal Pro is expensive, but it should last—Malden Mills says it’s the most durable fleece. My R2 jacket is several years old and has had much use, and it’s still in good condition. I most often use it on day hikes, but I do occasionally take it backpacking when the weather may be cold and wet.

WINDPROOF FLEECE The most wind-resistant fleece is probably Polartec Wind Pro, said to have four times the wind resistance of other fleece (which is not saying much) because of its tight construction. Wind Pro will keep out cool breezes, but that’s all. To make fleece fully windproof you have to add a windproof layer. This can be a thin nylon or polyester shell or lining or a membrane. Shelled and lined fleece garments are bulkier and heavier than standard fleece. They are very warm but not very versatile, since you can’t separate the layers. The fabric actually called windproof fleece has a thin windproof membrane sandwiched between two layers of light fleece and looks like conventional fleece. There are two major windproof fleece fabrics: Malden Mills’ Polartec Windbloc and W. L. Gore’s Windstopper fleece. Fabrics come in different weights, and garments weigh 18 ounces or more. Windproof fleece isn’t as breathable as standard fleece or as fast at moving moisture. It’s far warmer than standard fleece in any sort of wind but not as warm weight-for-weight in still air. It will also keep out showers, though not continuous heavy rain. If you do get it wet, it doesn’t dry fast. I’ve tried several garments, and in all of them I’ve quickly overheated when walking uphill, even in cold, windy weather. There are some backpackers—like my partner, Denise—who can walk all day in windproof fleece without getting sweaty, so if you run cold rather than hot, it could be the answer for cold-weather backpacking. For me an ordinary fleece top and a separate wind shell are far more comfortable and versatile. That said, I have a Mountain Hardwear Windstopper Vest that I sometimes pack when I want an extra warm garment just in case the weather is cooler than expected. It weighs 11 ounces and packs quite small. Slipped on over a base layer at rest stops, it’s just enough to stop me from cooling down.

WATER REPELLENCY Even though fleece is nonabsorbent and quick drying, moisture can be trapped between the fibers, especially in thicker and windproof garments, which slows the drying time and makes them feel damp. Some fleece fabrics have water repellency applied during manufacture; these quickly shed light rain and snow and don’t hold moisture in the fibers, which speeds drying. You can improve the water repellency of any fleece by treating it with a wash-in waterproofing agent such as Nikwax PolarProof or Granger’s Extreme Wash In.

RECYCLED FLEECE Some fleece is made from recycled polyester and plastic soda bottles, which reduces the use of oil and natural gas (used in manufacturing polyester) and keeps plastic bottles out of landfills. Dyersburg ECO Fleece, Draper’s EcoPile, Wellman’s EcoSpun, and some Polartec Classic fleece are all made from recycled polyester. Patagonia was the first company to use recycled fleece, back in 1993, and it’s found in the Retro Cardigan and some of the Synchilla clothing such as the Synchilla Vest and the Synchilla Marsupial top.

For many years waterproof-breathable garments were promoted as being the only shells needed, able to protect from both wind and rain. While this is true, even the best waterproof fabrics are far less breathable than those that are windproof but not waterproof. Wind shells are also softer, more flexible, more comfortable, and more durable than waterproof-breathable shells. I’ve always carried a wind shell as well as a rain jacket. Indeed, a wind shell is the piece of clothing I use most. It may appear as extra weight given that you still have to carry a rain shell, but it needn’t be. A light rain shell is all that’s needed, even in severe storms, because you can wear it with your wind shell for greater protection. It’s the layering principle again. A wind shell and a light rain shell are more versatile than a standard-weight rain shell. The warmth a thin wind shell provides is surprising. Pull one over a base layer or a fleece garment and you’ll notice the difference even in still air.

Wind shells—simple garments with few features, made from a single layer of untreated fabric—were too basic and low-tech to attract much attention from the marketing people until the turn of the twentieth century. Then, spurred by some new high-tech fabrics, outdoor clothing designers suddenly discovered that waterproof-breathable garments weren’t suitable for all conditions and that much of the time water-resistant, windproof, highly breathable clothing was more versatile and more comfortable. The marketers called this supposedly new clothing soft shell and called rain gear hard shell. The exact meaning of soft shell is disputed. The debate seems arcane and rather unhelpful, but overall the term is applied to fairly thin windproof garments with varying degrees of water resistance.

Soft shell, then, is a new name for an old idea. Having praised wind shells for years, I’m happy to see them suddenly become the in thing, even if it took a new name to achieve it. The benefit for backpackers not concerned with the latest fashions is that there are far more garments in different styles and fabrics than there used to be. The most basic are old-style wind shells, made from a single layer of uncoated nylon or polyester. Worn over a fleece top, they keep out a surprising amount of rain. They can be extremely light. Montane’s Aero Smock, made from Pertex Quantum nylon, weighs an astonishing 2.68 ounces. It has a mesh pocket on the chest plus a short zipper at the neck. I have Montane’s Featherlite Smock, made from Pertex Microlite and weighing 3 ounces. It has no features other than Lycra cuffs and hem and a short neck zipper, but it keeps out the wind and packs down small enough to hold in my fist. Patagonia’s Dragonfly and Marmot’s Chinook, made from ultralight nylon, weigh 3 ounces and have hoods and pockets. My favorite wind shell weighs slightly more, 5.29 ounces. This is the Montane Lite-speed, made from Pertex Microlite nylon. It’s a bit longer than the lighter garments, and has a full-length front zipper, a double-layer hood, and a chest pocket. Wind resistance and breathability are both excellent, and water resistance is surprising for such a thin garment. Note that ultralight garments like these don’t have great abrasion resistance and so aren’t ideal for scrambling or bushwhacking. Most garments weigh a little more than these, but anything over 12 ounces is unnecessarily heavy.

Pertex is an excellent material for wind shells, but there are others, such as Supplex, Versatech, Clima-Guard, Silmond, and Tactel, plus proprietary ones such as The North Face’s Hydrenalite. Some makers just use unbranded nylon and polyester. Many of these fabrics are made from microfibers, which have a denier less than 1: that is, each fiber weighs less than a gram per 9,000 meters, which is a hundred times finer than human hair. Microfibers are soft, supple, strong, and very comfortable. Because more fibers are packed into each thread, microfibers are very windproof and water resistant, since air spaces are fewer and smaller than in higher-denier fabrics. There are two variants on the original wind shell idea: shells treated to increase water resistance and shells with a wicking lining that increases warmth and means they can be worn next to the skin. Once you apply a coating to a fabric, however, you reduce the breathability even if it still isn’t fully waterproof. Garments that don’t keep out heavy rain yet aren’t very breathable seem a bad compromise to me, and I’ve never liked them. The purpose of a wind shell is to resist wind and be highly breathable, not to be a poor imitation of a rain jacket. However one company, Nextec, has come up with a way to increase a fabric’s water resistance without affecting the breathability much. This is done by encapsulating the individual fibers in silicone rather than applying a coating. This leaves microscopic gaps between the fibers through which body moisture can escape. Fabrics treated like this are highly water resistant and won’t absorb moisture, making them very quick drying. The treatment, called EPIC (encapsulated protection inside clothing), can’t be washed out, and there’s no coating to wear off or membrane to tear (don’t wash the garment in detergent, though—it ruins the water repellency). I’ve been impressed with the GoLite Flow jacket, made from EPIC-treated polyester. It’s not fully waterproof, but it will resist heavy showers and prolonged light rain. Breathability is far better than with fully waterproof fabrics, and I’ve had very little condensation. The Flow is no longer available but Wild Things makes a hooded EPIC jacket/windshirt weighing 8 ounces that appears to be a good substitute.

Line a wind shell with a thin base-layer fabric and you have a garment that can be a base layer or a midlayer and that is windproof, fast wicking, and surprisingly warm for the weight. There are many of these garments; the classic is Marmot’s DriClime Windshirt, made from nylon with a brushed DriClime wicking lining. It has a full-length zipper, a large chest pocket, and weighs just 10 ounces. Slightly heavier at 13 ounces is the Patagonia Stretch Zephur Jacket, made from polyester with a brushed polyester lining. I’ve tried both, and they are comfortable next to the skin, wick moisture fast, dry quickly, and keep out brief showers and light rain. Slightly heavier but also a touch warmer is the hooded Rab Vapour Rise Trail Smock. This is made from Pertex Equilibrium, a polyester-nylon bicomponent fabric that wicks moisture really fast, with a brushed polyester lining. This easily replaces a fleece top and will cope with all but the worst weather without need of a shell. Even so, I find two separate layers more versatile so I mostly wear these tops on day hikes or in dependably cool and windy weather.

The fabrics that have stirred such interest in wind shells are stretch nylons with smooth outsides and brushed insides such as those from the Swiss company Schoeller and laminated stretch fabrics with a windproof membrane such as Gore Windstopper and Polartec Power Shield. The last two are really thin versions of windproof fleece. Although they come in different weights, all these fabrics are thicker, warmer, and heavier than simple nylon and polyester. The lightest and thinnest garments are roughly comparable to a midweight base layer plus a wind shell, the heaviest to a 100-weight fleece plus a shell. The laminated fabrics are more wind and water resistant but less breathable than the nonlaminated ones. None of them are fully waterproof, though Windstopper and Power Shield come close. To find out how they perform and how they might fit into a hiker’s wardrobe, I tried four of these garments: the 19-ounce Mountain Hardwear Velocity, made from Schoeller Dryskin Extreme; the 21-ounce GoLite Path, made from Schoeller 3XDRY Extreme; the 16-ounce North Face Apex 1, made from stretch nylon; and the 20-ounce Arc’teryx Gamma MX Hoody, made from Polartec Power Shield Lightweight. They all coped with wet and windy weather, they all felt comfortable, and they all wicked moisture quickly. Yet I wouldn’t take any of them on a backpacking trip. They’re just too heavy and bulky for the warmth they provide. They’re also expensive. Proponents—and there are many—say they keep you warm with fewer layers, increasing freedom of movement and comfort. Maybe so, but they’re not as versatile or as warm as three separate layers: a simple wind shell, a base layer, and a 100-weight fleece. They’re probably fine for cold-weather climbing and mountaineering, but they’re not ideal for backpacking. Designers have fallen in love with them, though, and are having great fun combining fabrics and building garments that look beautiful and feel sensuous. The 19-ounce Marmot Super Hero Jacket, for example, is made from five fabrics—Windstopper Triton across the shoulders for water resistance, Power Shield under the arms for breathability, Polartec Wind Pro and Windstopper N2S on the body for warmth, and Windstopper Fitzroy on the arms and sides for reinforcement. Impressive! But do you need it?

I haven’t rejected stretch soft shell fabrics totally, though, and I do sometimes carry a Windstopper N2S base-layer top (see page 140) or a thin stretch nylon North Face Apex Zip Shirt instead of a 100-weight fleece when the weather looks reliably windy. At 11 and 12.5 ounces, respectively, these simple pullover tops weigh less than fancier soft shells. Slightly heavier at 13.8 ounces but more rain resistant and more versatile is the GoLite Kinetic jacket, made from the lightest version of Power Shield with Power Stretch panels over the shoulders. The Kinetic has zip-off sleeves, leaving a 9.5-ounce vest that makes a good backup garment in cool damp windy weather. I treat these soft shells as alternatives to light fleece and sometimes wear a thin wind shell over them, which adds quite a bit of warmth and water resistance.

Many wind shells are pullovers, which are usually lighter than jackets and often more comfortable when worn as a shirt in camp. They’re usually short, so they won’t extend below a rain jacket worn over them. The size should be adequate for wearing over other midlayers. Useful though not essential features are hoods, map-sized chest pockets, and adjustable cuffs. Even unlined wind shells can be worn next to the skin, although they may feel a little clammy when you’re on the move.

While several thin layers are best when hiking, since you can add and subtract layers to suit the conditions, one thick, warm garment for camp and rest stop wear is worth carrying in all but the mildest weather. This garment could be a thick fleece such as Thermal Pro or Polartec 300, which are especially good in cold, wet weather. However, garments filled with down or synthetic insulation are warmer, weigh less, and pack smaller. They are breathable and windproof, too, so you don’t need a shell over them except in rain. I find they warm me psychologically as well as physically. Just knowing I have a thick, puffy garment stowed in my pack helps me feel warm on a cold day. Simple designs are best, since they weigh least. The only features I look for are insulated hand-warmer pockets. Hoods are nice, but a hat does just as well.

The GoLite Kinetic jacket is a versatile soft shell.

Vests make good insulating garments because they keep your core warm and are light and low in bulk. On Pacific Crest Trail, Continental Divide, and Arizona Trail hikes, I carried insulated vests—down on the PCT and AZT and synthetic on the CDT. In combination with a fleece top when the temperature occasionally fell well below freezing, these were just enough to keep me warm in camp. If weight isn’t critical, I often carry a jacket or a sweater, which weighs more than a vest but provides more warmth.

Down from ducks and geese is still the lightest, warmest insulation, despite all attempts to create a synthetic that works as well. Garments filled with down pack small and, weight-for-weight, provide much more warmth than fleece or synthetic fills. They’re too hot to wear when walking unless it’s extremely cold, but they’re ideal at rest stops and in camp. Down is very comfortable, and its thickness is reassuring. It looks and feels warm. There’s nothing like snuggling into a down garment in freezing weather. Down is expensive, but it’s also very durable and will long outlast any synthetic fill. However, it must be kept dry: when sodden it loses its insulating ability, and it dries very slowly unless you can hang it in the hot sun or put it in a machine dryer. Down can absorb vast amounts of water, so a soaked down garment is also very heavy to carry. But keeping down dry isn’t difficult if you carry it in a waterproof stuff sack and wear it only in a tent or under a tarp if it’s raining. Despite this, I still carry a down top only when rain isn’t likely, since I may want to wear it outside. If you really want to use a down top in wet weather, you can get down jackets with water-resistant shells like Dryloft or EPIC. They’re more expensive than standard shells and in my experience slightly heavier and not quite as breathable. Also, if the weather is wet it won’t be freezing, so a down top isn’t needed; a light synthetic one will be adequate.

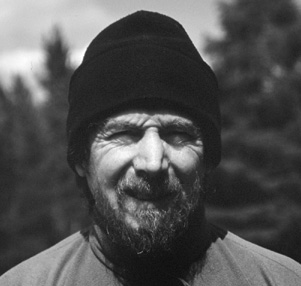

A down jacket, a fleece hat, and a hot drink keep the author warm on a frosty fall morning.

The thickness of an insulated garment is the best guide to its warmth. This is known as the loft. Down comes in different grades, measured by how many cubic inches an ounce of down will fill. This is known as the fill power, and the higher the number, the more loft a given weight of down will provide. For example, 750-fill-power down is warmer weight-for-weight than 550-fill power.

For backpacking, a light down garment with sewn-through seams (where the stitching goes right through the garment—see the sleeping bag section in Chapter 6 for more on this) is all you need. Complex constructions, vast amounts of fill, and heavy waterproof-breathable shells are for Himalayan mountaineers and polar explorers. Garments suitable for backpacking need weigh no more than 25 ounces. For years I’ve used a Marmot Down Sweater filled with 650-fill-power down. This weighs 21.5 ounces and has an average loft of 2.5 inches (measured by placing a ruler across the garment in several places and reading off the height above the ground). The Down Sweater has a nylon shell, hand-warmer pockets, a down-filled baffle behind the front zipper, and a stand-up collar. This top has kept me warm in freezing temperatures for many years now, and until recently it seemed quite light for the warmth provided. But I’m being seduced away from my old friend by the delightful Western Mountaineering Flight jacket, which weighs an astonishing 10.5 ounces yet has the same loft (though the sweater is several years old while the Flight has been worn only a few times; the sweater may have had more loft when new). The design is the same as the Down Sweater too, except that the pockets don’t have zippers and it’s a little shorter, reaching just below the waist. It’s the materials that differ. The Flight has an ultralight 0.9-ounce taffeta-nylon shell stuffed with 800-fill-power down. Western Mountaineering also makes a vest (and the company actually does make its products rather than importing them) called the Reactor that has the same fill and shell and weighs just 8 ounces. By contrast, Marmot’s Down Vest, which I took on the Arizona Trail, weighs 14.5 ounces. There are many other good down garments from companies like Feathered Friends (especially the 16-ounce Helios), The North Face, Mountain Hardwear, Patagonia, Nunatak, GoLite, Rab, and PHD (Peter Hutchinson Designs), but none is as light as the Flight.

Down garments are excellent in cold, dry weather.

The Helly Hansen Thin Air Vest filled with Primaloft One is warm and light.

For wet-cold conditions, synthetic-filled garments are a good choice. They don’t absorb much moisture, keep some of their warmth when damp, and dry quickly, so they perform better than down when wet. They’re not as warm for the weight when dry, however, and they’re bulkier when packed. They’re warmer and lighter than heavy fleece garments, though. The best synthetic fills have good durability, but they still won’t last as long as fleece or down. Although not as thick as down garments, they’re soft and comfortable. You can choose from several fills. Primaloft and Polarguard are generally regarded as the best, with Thermolite Micro not far behind. Polarguard is well established as a warm, durable fill. It’s a continuous polyester filament rather than a mass of short fibers. The filaments are hollow and trap air for greater warmth. Both materials come in several versions, of which Polarguard Delta and Primaloft One are regarded as the best. Primaloft is a very soft hydrophobic microfiber. Both materials are more compressible than other synthetic fills and resist moisture well. Primaloft is the softer of the two and drapes around the body better, but there’s not much difference between them. The jacket I’ve used most is the hip-length GoLite Coal, which is filled with Polarguard Delta, has a ripstop nylon shell (Polarguard Delta and Pertex nylon-polyester shell in the latest models), and weighs 19 ounces (16.5 ounces without the detachable hood). The loft is 1 inch, less than half that of the down tops described earlier. The Coal is comfortable, will resist a fair amount of rain, and has kept me warm in temperatures down to 25°F (−4°C). The Coal has been replaced by the Belay parka, which weighs the same but is shorter and has an attached hood. If it’s not likely to be that cold, I carry a lighter garment, the Rab Photon Primaloft One smock, which has a Pertex Quantum shell and weighs 12.5 ounces, with a loft of just under half an inch. The Photon is a pullover with a long front zipper and hand-warmer pockets that are accessible when you’re wearing a pack hipbelt. It’s very soft and comfortable, and I have occasionally hiked in it when the weather has been colder and windier than expected. If it’s unlikely that I’ll need an insulated garment but I want something just in case, I often carry a Primaloft One–filled Helly Hansen Thin Air Vest, which weighs 10 ounces and has a polyester microfiber shell and hand-warmer pockets. The loft is 0.67 inch. Patagonia makes a similar vest, the Puffball, filled with Thermolite Micro and also weighing 10 ounces. There are many others.

Synthetic insulated garments don’t compact as well as down garments, but they do pack down much smaller than equivalent-warmth fleece. However, compression is bad for synthetic fills, and repeated or prolonged compression can flatten the fill so it loses its loft. To get the maximum life out of my synthetic garments, I pack them at the top of the pack, using them to fill out any remaining space. I don’t stuff them into the small stuff sacks usually provided with them or load heavy items on top of them.

Keeping out wind, rain, and snow is the most important task of your outer clothing. If this layer fails in heavy rain, it doesn’t matter how good your other garments are—wet clothing exposed to the wind will chill you, whatever material it’s made of. In wet clothes you can go from feeling warm to shivering and being on the verge of hypothermia very rapidly, as I know from experience. Rain clothing must be waterproof; it’s more comfortable if it also lets out at least some body moisture.

Don’t, however, expect too much from rain gear. In heavy showers you can expect to remain pretty dry. At the end of a day of steady rain you’ll probably be damp, even in the best waterproof-breathable rain gear, because the high humidity will restrict the fabric’s breathability. In non-breathable rain gear you’ll be wet from condensation. If rain continues nonstop for several days so that you can’t dry anything out, you’ll get progressively wetter, however good your rain gear. This is where wicking inner layers and fleece mid-layers make a difference—they are still relatively warm when damp, and they dry quickly. A wind shell worn under your rain gear will help protect inner layers from condensation on the inside of the rainwear.

Rain jacket worn for protection on a damp, misty day.

If rain keeps up for more than a few days, it’s a good idea to head out to where you can dry your gear. The wettest walk I’ve ever done was an eighty-six-day, south-to-north trek through the mountains of Norway and Sweden. It rained most days, and on several occasions it rained nonstop for a week. The only way I could get my gear and myself dry was to spend an occasional night in a warm mountain hut or a village hotel.

When the water vapor your body gives off eventually hits your outer layer, it will condense on the inside unless it can pass through the fabric or escape through vents. Over time, this condensation can eventually soak back into your midlayers, leaving you feeling damp and chilly.

The first waterproof fabric that allowed inner moisture to escape with any success was Gore-Tex, which started the waterproof-breathable revolution back in the 1970s. Since then a host of waterproof fabrics have appeared that transmit water vapor to some degree, though Gore-Tex still leads the market. These fabrics work because of a pressure differential between the air inside the jacket and the air outside; your body heat pushes the vapor through the fabric. The warmer the air, the more water vapor it can hold. Since the air next to your skin is almost always warmer than the air outside your garments, it contains more water vapor, even in the rain. Condensation forms on the inside of shell garments when the air in your clothing becomes saturated with vapor that cannot escape. This vapor hits the inside of your shell and condenses on the cool surface. But a breathable fabric lets at least some vapor pass through as long as the outside air is cooler than the inside air. (Theoretically, waterproof-breathable fabrics can work both ways, but when rain clothing is needed the outside air temperature is always lower than your body temperature.) Breathable garments need to be relatively close-fitting to keep the air inside as warm as possible so the fabric can transmit moisture more effectively. However, ventilating any garment by opening the front, the cuffs, and any vents and lowering the hood is still the quickest and most efficient way to let moisture out.

Breathable fabrics aren’t perfect, of course, and they won’t work in all conditions. There’s a limit to the amount of moisture even the best of them can transmit in a given time. When you sweat hard, you won’t stay bone dry under a breathable jacket, nor will you do so in continuous heavy rain, despite makers’ claims. When the outside of any garment is running with water, breathability is reduced and condensation forms. It’s hard for water vapor to be pushed through a sheet of water. With the best fabrics, once your energy output slows down and you produce less moisture or once the rain stops, any dampness will dry out through the fabric. In very cold conditions, especially if it’s also windy, condensation may freeze, creating a layer of ice inside the garment. The easiest way to get rid of this is to take the garment off and shake it.

In wet-cold weather, you need warm clothing between your base layer and your shell. How much depends on your level of activity. Clothing that is too thick compromises breathability. Nick Brown of Páramo has calculated that more than 1/15 inch of insulation will significantly reduce breathability. Many heavy fleece garments are thicker than this. It’s best to wear only enough clothing to keep you just warm while moving rather than trying to feel toasty.

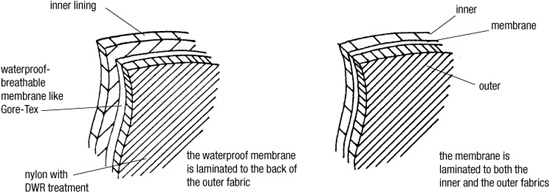

There are two main categories of breathable materials: polyurethane coatings and membranes (see sidebar, page 149). From all the fancy names, you’d think there were vast numbers of coated fabrics. Actually there are only a few, since many garment makers assign their own names to the same fabrics. Proprietary names include Triple-point Ceramic (Lowe Alpine), Helly Tech (Helly Hansen), H2NO (Patagonia), HyVent (The North Face), PreCip (Marmot), Elements (REI), Microshed (Solstice), Texapore (Jack Wolfskin), Omni-Tech (Columbia Sportswear), and Camp-Tech (Campmor). Many makers use Entrant, though not always under that name.

Waterproof (two- or three-ply laminate) (left) and three-layer laminate (right).

Coatings are as waterproof as membranes, but just as they started approaching membranes in breathability, new membranes came along that are definitely superior. I get damp more quickly in even the best coated fabrics (such as Marmot PreCip) than I do in membranes like eVENT and Paclite. However, there is a new polyurethane coating from Toray called Entrant G2 XT that is designed to be almost as breathable as the best membranes. I haven’t tried this yet but it sounds promising.

Membranes are arguably the most effective (and most expensive) waterproof-breathable fabrics. There are far fewer membranes than coated fabrics, with just one generally available—Gore-Tex. Sympatex is still around but is used by only a few makers. However, a new one, called eVENT, looks very promising. Pearl Izumi, Jagged Edge, Montane, and Rab all make eVENT garments. There are a few proprietary membranes, such as Alchemy (GoLite) and Conduit (Mountain Hardwear). An unusual membrane is 3M’s Propore, a microporous polypropylene membrane laminated to nonwoven polyurethane to produce a very soft fabric used in Rainshield clothing made by ProQuip. A similar polypro membrane and nonwoven polypro fabric are used by Frogg Toggs.

Gore-Tex and eVENT are microporous membranes (see sidebar, page 149) made from expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE). Sympatex is a hydrophilic membrane made of polyester. Gore-Tex has become a family of fabrics, with the original version joined by XCR (extended comfort range), which is more breathable, and Paclite, which is lighter and more breathable though not as tough as XCR. First-generation Gore-Tex was very breathable, but once contaminated with oil, whether from sweat, sunscreen, or some other source, it leaked—as I found out most unpleasantly on a cold, wet, windswept mountain pass. In second-generation Gore-Tex a thin layer of polyurethane was put over the membrane to protect it. This solved the oil problem but reduced the breathability. However, BHA Technologies claims its eVENT membrane is oil repellent so that a polyurethane coating isn’t needed and water vapor can pass through the pores in the membrane without having to be absorbed into the polyurethane first, a process BHA calls “direct venting.” I’ve tried eVENT garments from Rab, Montane, and Lowe Alpine, and they are noticeably more breathable than any other membrane or coated fabric I’ve worn. Paclite, which has an inner layer consisting of carbon and an oleophobic (oilhating) substance, is the most breathable Gore-Tex material.

Membranes can be laminated to a variety of nylon and polyester fabrics. The thicker the fabric, the more durable the garment. In three-layer laminates, the membrane is glued between two layers of fabric to produce a material that is hardwearing but slightly stiff. Because the membrane is protected by fabric on both sides, three-layer laminates are the most durable constructions. Less durable but softer are two-layer laminates, in which the membrane is stuck to an outer layer while the inner lining hangs free, and drop liners, in which the membrane is left loose between the inner and outer layers. Finally, there are lining laminates, also described as laminated to the drop, where the membrane is stuck to a very light inner layer. This design minimizes the number of seams, which is a bonus. Drop liners and lining laminates are now rarely used in hiking clothing.

The disadvantages of coatings and membranes are that the barriers aren’t very durable, can’t be reproofed when they start to leak badly, and transmit only water vapor, not liquid sweat. However, Páramo Directional Waterproofs, from the company that makes Nikwax proofing products, are very durable, can be reproofed, and allow sweat through to the outside. There are no coatings or membranes. Instead, Páramo mimics the way animals stay dry—a unique waterproof-breathable system that inventor Nick Brown calls the Nikwax biological analogy. This system requires a two-layer material.

The inner layer of a Páramo Directional Waterproof is a very thin polyester fleece, called the Nikwax Analogy Pump Liner, whose fibers are tightly packed on the inside but become less dense toward the outside, like animal fur. To replicate the animal oils that keep fur water repellent, Parameta is coated with Nikwax TX.10. Like fur, Parameta pumps water in one direction only—away from the body. It does this more quickly than rain can fall, so moisture is always moving away from the body faster than it arrives, keeping you dry.

To be effective on its own, the Pump Liner would have to be very thick, however. To keep it thin (and therefore not too warm or heavy), Páramo garments have an outer layer of windproof polyester microfiber that deflects most of the rain. The combination of these two fabrics allows more moisture to get out, including condensed perspiration, than any membrane or coating. It’s not dependent on humidity levels outside the garment or on the temperature inside. The whole garment, including zippers and cords, is treated with TX.10, so it won’t absorb moisture or wick it inside.

I’ve been using Páramo waterproofs since they first appeared in the early 1990s, and I’ve found them very comfortable and efficient. Because there is no coating or laminate, they are very soft and comfortable, feeling more like a soft shell than a waterproof. Reproofing works, and the garments last a long time. There are two limitations. The two-layer construction makes them rather warm and fairly heavy—the lightest Páramo jacket, the Cuzco, weighs 25 ounces. Effectively, you are wearing a wind shell and a base layer. This makes them too warm for me in summer, although some people find them comfortable year-round. From fall to spring, however, I find Páramo jackets and pants comfortable and have never gotten wet or suffered condensation in them. Because the garments are very soft and the lining wicks moisture, you can wear them next to the skin, so you need only one layer instead of three. They are far more effective than any of the new and much touted soft-shell fabrics because they are fully waterproof while being just as breathable and comfortable.

Nonbreathable waterproof clothing is made from nylon or polyester, usually coated with polyurethane or polyvinyl chloride (PVC), though occasionally with silicone. Its greatest advantage is that it’s far less expensive than waterproof-breathable fabrics. Polyurethane is much more durable than PVC, though both eventually crack and peel off the base layer. Cheap vinyl rain gear lasts about as long as it takes to put it on and isn’t worth considering, despite the price. Because moisture can’t escape through the fabric, condensation is copious if you wear nonbreathable garments for long. The only way to remove that moisture is to ventilate the garment, hardly practical while the rain is pouring down. One way to limit the dampness is to wear a windproof layer under the waterproof one, which traps some of the moisture between the two layers.

While you’re hiking you’ll still feel warm, even if you’re very damp with sweat, because nonbreathable rainwear holds in heat as well as moisture. When you stop, though, you’ll cool down rapidly unless you put on dry clothes. It’s far better to get damp with sweat than wet from rain, however. Until the late 1970s all rain gear was nonbreathable, and people still hiked the Appalachian Trail in the rain and slogged through the wet forests of the Pacific Northwest.

Weights of nonbreathable rain tops start at 6 ounces. Few name brands offer nonbreathable rainwear. Two that do are Sierra Designs, whose polyurethane-coated Backpacker’s Jacket weighs 11.3 ounces, and Stephenson’s Warmlite, whose silicone-coated nylon rain jacket weighs 6 ounces.

Material alone is not enough to ensure that a garment will perform well—design also matters. The two basic choices are jackets with full-length zippers and pullovers. I’ve tried both, and I much prefer jackets, since they are so much easier to get on and off. That old standby the poncho is still popular with some backpackers. Ponchos are versatile; they can double as tarps or ground cloths. They have good ventilation, too, but they can act like sails in strong winds, making them unsuitable for windy places. Ponchos are usually made of non-breathable fabrics. Examples are Stephenson’s Warmlite poncho and GoLite’s Ultra-Lite Poncho, both made from silicone-coated nylon, which weigh 8 ounces. Hilleberg makes a curious waterproof-breathable garment called the Bivanorak (18 ounces). It’s a poncho-style garment that covers you and your pack but has sleeves and can also be used as a bivouac bag or sleeping bag cover.

Length is a matter of personal choice. I like hip-length garments because they give my legs greater freedom of movement, but many people prefer longer ones so they don’t need rain pants as frequently.

Seams are a potential leak point in any waterproof garment. Only Páramo garments have seams that don’t leak without being sealed, because they are treated with TX.10 and are water repellent. In waterproof-breathable garments and the more expensive nonbreathables, seams are usually taped, the most effective way of making them watertight. In cheaper garments, seams may be coated with a special sealant instead. If you have a garment with uncoated seams, you can coat them yourself with urethane sealant. You also can do this when the original sealant cracks and comes off—as it will. Taped seams can peel off, though this is rare. Even so, the fewer seams, the better. The location of the seams is important, too. The best garments have seamless shoulder yokes to avoid abrasion from pack straps.

The front zipper is another possible source of leaks. Standard zippers should be covered with a single or, preferably, double waterproof flap, closed with snaps or Velcro. The covering flap should come all the way to the top of the zipper. Many garments now have watertight zippers, first introduced by Arc’teryx, which are coated with urethane and have flaps that close over the zipper teeth. In my experience these are near enough to being waterproof, though driving rain can sometimes work its way in. I’ve never had much rain enter, though, and I like not having to fasten double flaps. The lack of bulk and slight weight reduction is welcome too. Most zippers open from the bottom as well as the top. These are slightly more awkward to use than single-direction zippers and have no advantages that I can see except perhaps to allow ease of movement and access to pants pockets in very long garments.