WITH HIS PACK BULGING AND STUFF SACKS STRAPPED ON TOP OR HANGING BELOW, HE GRUNTS ALONG, SWEAT POURING FROM HIS OVERWORKED BODY. MAYBE YOU CAN’T TAKE IT WITH YOU, BUT THIS FELLOW WILL OBVIOUSLY TRY.

—Backwoods Ethics, Laura and Guy Waterman

The heart of the backpacker’s equipment is the pack. Tents, boots, stoves, and rain gear may be unnecessary at some times and places, but your pack is always with you. It must hold everything you need for many days’ wilderness travel yet still be as small a burden as possible.

Ever since aluminum frames and hipbelts were introduced in the 1940s and 1950s, designers have tried to make carrying loads as comfortable as possible. Internal and external frames, adjustable back systems, sternum straps, load-lifter straps, side tension straps, triple-density padded hipbelts, lumbar pads—the modern pack suspension is a complex structure that requires careful fitting. Only your footwear is as important to your comfort as your pack, so take the time to find a pack that fits.

The last decade of the twentieth century saw a huge change in pack design—a revolution even, though I’m wary of that word—with the advent of lightweight and ultralight packs weighing a small fraction of the weight of earlier packs. This shook up the pack world, and established makers scrambled to produce their own lightweight designs. Except for long cold-weather trips, there’s now no need to carry a pack weighing even half what standard packs used to weigh. An added bonus is that these lightweight packs are usually less expensive than heavier ones.

Walk into any outdoor equipment store and you’ll be confronted by a vast array of packs. Any could be used for backpacking; the problem is to determine which are right for your kind of backpacking. Many people use one pack for all their hiking. If you do, then you need a pack with enough capacity for the bulkiest loads you’re likely to carry. Overstuffing a too-small pack is not the way to achieve a comfortable carry. If you go on trips year-round, you may be better off with more than one pack, so you can tailor the load to their capacity and weight. I now regularly use three packs: a 21.5-ounce, 4,000-cubic-inch frameless pack for trips where the load will be less than 30 pounds; a more supportive 39.8-ounce, 4,000-cubic-inch internal frame pack for loads between 30 and 45 pounds; and a 115.6-ounce, 7,200-cubic-inch internal frame monster for even heavier loads. A pack designed to carry 60 pounds comfortably will be fine with 30 pounds, but the converse is not usually true. If I could keep only two packs, I’d drop the lightest one. If I could keep only one, it would be the heaviest. Of course if you do only short three-season hikes with light loads, then you’ll need only a light, relatively inexpensive pack. You can always add a larger, heavier pack if you decide on longer or colder-weather hikes and an even bigger one for extended cold-weather trips.

Before I go into the details of pack design and construction, here’s a brief overview of types of packs.

The new ultralight packs weigh about a pound and are designed for loads up to 20 pounds. These packs have minimal features, with no frames and often no back padding or hipbelts. Once you’d probably have had to make such a pack yourself, but now several are sold by companies like GoLite, Lynne Whelden’s LWGear, and Gossamer Gear (formerly GVP). The pack that started this revolution is the GoLite Breeze, designed by Ray Jardine based on the one he uses on his long-distance hikes. The Breeze is as simple as can be—just a large nylon bag made from tough Dyneema gridstop nylon with padded shoulder straps, mesh side and rear pockets, and a rollover closure. The medium size holds 2,900 cubic inches, plus another 850 if you use the extension, and weighs 14 ounces. However, the title for lightest pack goes to the astonishing 7-ounce, 3,800-cubic-inch Gossamer Gear G5, which is made from 0.5-ounce ripstop nylon and has a webbing belt and mesh pockets. Gossamer Gear packs are designed to use a foam pad as a frame and to have small items of clothing stuffed into the shoulder straps and hip-belt as padding, though you can use small foam pads. The G5 is clearly a specialist pack that won’t be very durable—Gossamer Gear describes it as for the “fanatic” ultralight hiker. Gossamer Gear’s other pack, the Mariposa (formerly G4), has a similar design, weighs 18 ounces with all options and 15 ounces stripped, and has a capacity of 4,600 cubic inches. It’s made from 2.2-ounce ripstop nylon, more durable than the 0.5-ounce but still not tough. The mesh used for Lynne Whelden’s One Pound Pack, a 3,500-cubic-inch model that actually weighs 12.5 ounces, should be harder-wearing. I’ve tried the GoLite Breeze and the Gossamer Gear Mariposa/G4 packs, and although they’re fine with loads under 20 pounds, they’re a little too minimalist for me. Using them reminded me why padded backs, frames, and hipbelts were developed.

An ultralight pack. GoLite Breeze.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: (1) Ultralight pack with mesh pockets (GoLite Breeze), suitable for loads up to 20 pounds. Front view. (2) Lightweight pack with lightly padded back and unpadded hipbelt (GoLite Gust), suitable for loads up to 30 pounds. Back. (3) Lightweight pack with lightly padded back and unpadded hipbelt (GoLite Gust), suitable for loads up to 30 pounds. Side. (4) Lightweight pack with padded back, framesheet, and padded hipbelt (ULA P-2), suitable for loads up to 40 pounds. Front. (5) Lightweight pack with padded back, framesheet, and padded hipbelt (ULA P-2), suitable for loads up to 40 pounds. Back.

Add a little more weight and a few more features, and there are plenty of day packs in the 1,800- to 2,500-cubic-inch range weighing 1.5 to 2.5 pounds that could do for ultralight backpacking.

Not many people get their total loads below 20 pounds, but plenty carry no more than 25 to 45 pounds. For these weights you don’t need a fully specified heavy, traditional backpacking sack, but you do need more support than you get from an ultra-light pack with no frame or hipbelt. Lightweight packs weigh from 1 to 4 pounds and have capacities from 2,500 to 5,000 cubic inches. The most basic have padded backs but no frames and simple unpadded hipbelts. Thirty pounds is usually the comfort limit for these. Add an internal frame and a padded belt, and that limit goes up to as much as 50 pounds. Until the first ultralight packs appeared, lightweight packs were hard to find. At first I couldn’t find one I liked; now the problem is deciding which one to choose. The growing list includes:

A lightweight pack. ULA P-2. (Padded hipbelt not shown.)

Dana Design Racer X—variable capacity (you strap on dry bags or stuff sacks), 34 ounces

Dana Design Racer X—variable capacity (you strap on dry bags or stuff sacks), 34 ounces

GoLite Jam—2,500 cubic inches, 23 ounces

GoLite Jam—2,500 cubic inches, 23 ounces

GoLite Infinity—2,750 cubic inches, 39 ounces

GoLite Infinity—2,750 cubic inches, 39 ounces

GoLite Speed—3,400 cubic inches, 33 ounces

GoLite Speed—3,400 cubic inches, 33 ounces

GoLite Gust—3,900 cubic inches, 21 ounces

GoLite Gust—3,900 cubic inches, 21 ounces

GoLite Trek—4,800 cubic inches, 42 ounces

GoLite Trek—4,800 cubic inches, 42 ounces

Granite Gear Virga—3,400 cubic inches, 20 ounces

Granite Gear Virga—3,400 cubic inches, 20 ounces

Granite Gear Vapor Trail—3,600 cubic inches, 32 ounces

Granite Gear Vapor Trail—3,600 cubic inches, 32 ounces

Granite Gear Nimbus Ozone—3,800 cubic inches, 48 ounces

Granite Gear Nimbus Ozone—3,800 cubic inches, 48 ounces

Gregory G—2,900 cubic inches, 42 ounces

Gregory G—2,900 cubic inches, 42 ounces

Gregory Z—3,750 cubic inches, 50 ounces

Gregory Z—3,750 cubic inches, 50 ounces

Kelty Cloud 4000—4,000 cubic inches, 40 ounces

Kelty Cloud 4000—4,000 cubic inches, 40 ounces

Kiskil Outdoors Mithril—4,400 cubic inches, 20 ounces

Kiskil Outdoors Mithril—4,400 cubic inches, 20 ounces

McHale Spectra SUBPOP—3,500 cubic inches, 39 ounces

McHale Spectra SUBPOP—3,500 cubic inches, 39 ounces

Mountainsmith Auspex—4,200 cubic inches, 55 ounces

Mountainsmith Auspex—4,200 cubic inches, 55 ounces

One Pound Plus Pack—3,340 cubic inches, 23 ounces (available from both Lynne Whelden and Equinox)

One Pound Plus Pack—3,340 cubic inches, 23 ounces (available from both Lynne Whelden and Equinox)

Osprey Aether 60—3,700 cubic inches, 56 ounces

Osprey Aether 60—3,700 cubic inches, 56 ounces

Six Moon Designs Starlite—4,100 cubic inches, 27 ounces

Six Moon Designs Starlite—4,100 cubic inches, 27 ounces

Ultimate Direction WarpSpeed—3,000 cubic inches, 42 ounces

Ultimate Direction WarpSpeed—3,000 cubic inches, 42 ounces

ULA (Ultralight Adventure Equipment) P-2—4,025 cubic inches, 40 ounces

ULA (Ultralight Adventure Equipment) P-2—4,025 cubic inches, 40 ounces

ULA Fusion—3,500 cubic inches, 32 ounces

ULA Fusion—3,500 cubic inches, 32 ounces

Wild Things AT—5,000 cubic inches, 40 ounces

Wild Things AT—5,000 cubic inches, 40 ounces

Weights and capacities are size-dependent, of course. Most of these packs come in several sizes. The figures quoted are mostly for large sizes.

Despite the lightweight revolution, most packs still fall into the standard pack category, and there are dozens of models. I now use a standard pack only for loads of more than 45 pounds. I no longer carry that much very often, but when I do I still appreciate the comfort. These packs are sophisticated, complex, expensive, and marvelous. Without them, carrying heavy loads would be much more arduous. This category subdivides into two suspension systems based on frame type. Each system has its dedicated, vocal proponents.

First came the external frame of welded, tubular aluminum alloy; its ladderlike appearance was common on trails worldwide in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. It’s a simple, strong, and functional design, good for carrying heavy loads along smooth trails but unstable in rougher, steeper terrain. It’s easy to lash extra items to the frame, making capacities enormous.

Although external frames have been to the summit of Everest, mountaineers found them unstable for climbing, generally preferring frameless “alpine” packs that hugged the back closely.

Standard pack with internal frame and thick hipbelt (Gregory Shasta), suitable for loads of 50+ pounds. Back.

However, these were uncomfortable with heavy loads. To combine stability with comfort, flat, flexible metal bars were added to the backs of the alpine packs, stiffening them and making it easier to transfer the weight to the hips. Thus, in the late 1960s the internal-frame pack was born. The design developed rapidly, and today most backpackers choose internal-frame packs. Ranging in capacity from 3,000 to a frightening 9,000 cubic inches, they serve just about any sort of backpacking, from summer weekend strolls to six-month expeditions. Internal-frame packs require careful fitting and adjustment, but if you’re prepared to take the time for a proper fit, they’re an excellent choice.

External frames seem to be fading away. Backpacker magazine’s 2004 Gear Guide lists four companies that offer external-frame packs—and fifty that offer internals. And those four companies (Bergans, Coleman, JanSport, Kelty) offer more internal-frame packs than external-frame ones.

Travel packs are derived from internal-frame packs and have similar suspension systems and capacities. The frame and harness can be covered by a zippered panel when they’re not needed (or when you don’t want to risk the suspicion that packs engender in some officials and in some countries) and to protect them from airport baggage handlers. With the harness hidden, travel packs look like soft luggage, with handles, zip-around compartments, and front pockets, and they can be used like suitcases when packing and unpacking. My limited usage of one Lowe Alpine model suggests that they’re all right for the occasional overnight trip but don’t compare with real internal-frame packs for comfort, which seems to be the general consensus. The larger ones with internal frames are probably adequate for moderate loads (40 pounds or so) as long as you don’t mind the panel zippers.

The suspension system is the most important feature to consider when choosing a pack; it supports the load, and it’s the part of the pack that comes in contact with your body. A top-quality, properly fitted suspension system will let you carry loads comfortably and in balance. An inadequate or poorly fitted one can cause great pain. As with boots, it takes time to fit a pack properly. This applies even to frameless packs—they still need to be the right length for your back.

To hold the load steady and help transfer the weight from the shoulders to the hips, the back of the pack needs some form of stiffening. For loads less than 30 pounds, simple foam padding is adequate, but once the weight exceeds 30 pounds, a more rigid system is needed.

As I said earlier, there are two frame types: external, with the packbag hung on a frame by straps or clips or clevis pins, and internal, which fits inside the fabric of the pack, often completely integrated into it and hidden. The debate centers on which frame best supports a heavy load and which is more stable on rough ground; the answer used to be external for the first and internal for the second. Today, however, the best designs and materials have made the distinction less clear-cut.

For many years now my choice has been internal-frame packs. It’s a couple of decades since I last used an external frame. Internals are more stable than all but a few externals, easier to carry around when you’re not on the trail, and less prone to damage. Some are comfortable with any weight you’re likely to carry. That said, I have a friend who has used a Kelty Tioga external-frame pack for decades and finds it just about perfect. His only complaint is that he can’t replace it with an identical model. Since his stomping grounds are the Colorado Rockies and the Wind River Range and he likes challenging off-trail hikes above the timberline, he’s clearly adapted to the rigidity of the frame.

The traditional external frame is made of tubular aluminum alloy and consists of two curved vertical bars to which a number of crossbars are welded. Kelty introduced such frames back in the 1950s and still makes them in barely altered form for their Yukon and Trekker packs. Variations have appeared over the years, such as hourglass-shaped frames and frames made from flexible synthetic materials. External frames are usually not adjustable, though some have frame extensions for carrying larger loads while others telescope and come in different back lengths. Suspension systems are similar to those found on internals. With externals the weight transfers directly through the rigid frame to your hips, so they will handle very heavy loads comfortably as long as the hipbelt is well padded and supportive enough. Because of their rigidity, it’s easy to keep the weight high up and close to your center of gravity, enabling you to walk upright. Also, because the packbag is held away from the back, they allow sweat to dissipate, unlike internal-frame packs, which hug the body. Even so I’ve always found that when I work hard carrying a heavy load, I end up with a sweaty back whatever the type of frame.

The disadvantages of external frames are balance and stability. External frames do not move with you; on steep descents and when crossing rough ground, they can be unstable and may make walking difficult or even unsafe. They also tend to be bulkier than internal-frame packs, making them awkward for plane, car, and bus travel and difficult to stow in small tents. Their rigidity also makes them more vulnerable to damage, especially on airplanes. My last external frame cracked during airplane baggage handling.

Externals are generally less expensive than internals, though, and some are lighter for similar capacity and load-carrying comfort.

A few external frames are designed to gain the advantages of internals without losing the advantages of externals. They have modified frame shapes, often made from flexible plastic instead of rigid alloy. Kelty makes an hourglass-shaped aluminum frame (Tioga, Super Tioga, and their 50th Anniversary models) that “allow gear to ride close and high,” while the venerable JanSport frames have crossbars attached to the side bars by flexible joints, which, JanSport claims, allow the frames to twist and flex with body movement.

Not having used any of these frames, I can’t comment on how effective they are, but it seems that the key to better balance with an external frame is the hipbelt’s freedom of movement in relation to the pack, plus an increased curvature that molds the frame more closely to the body.

The basic internal frame consists of two flat aluminum alloy stays running vertically down the pack’s back. This original design, introduced in the late 1960s by Lowe Alpine, addressed the instability of external-frame packs on rugged terrain and the difficulty of designing a frameless pack to carry a heavy load comfortably. The bars, or stays, are usually parallel, though in some designs they form an upright or inverted V and in others an X.

Many internal frames now have flexible plastic framesheets in addition to or instead of stays to give extra rigidity to the pack and prevent hard bits of gear from poking you in the back. There are many variations on the framesheet/parallel stays theme, using aluminum, carbon fiber, polycarbonate, thermoplastic, Evazote, and polyethylene. Some packs have single stays down the center of the framesheet, and some have Delrin or titanium rods running down the sides to help transfer the weight to the hipbelt. One (McHale Bayonet) even has a two-part frame—remove the top for a smaller pack. Each pack maker has its own type of internal frame; all, of course, claim theirs can carry heavy loads more comfortably than anything else. The ones I’ve tested over the years—Aarn, Arc’teryx, Gregory, Dana Design, Lowe Alpine, The North Face, Osprey, Jack Wolfskin, and Marmot—all did a pretty good job with moderately heavy loads (45 to 55 pounds). Some—Dana Design, Arc’teryx, Gregory—will handle 60 pounds or more while some lightweight models (ULA P-2) will handle up to 40 pounds.

Whatever the style, internal frames are flexible and with use conform to the shape of the wearer’s back, allowing a body-hugging fit that gives excellent stability.

Because internal frames move with your body and let you pack the weight lower and closer to your back, they are excellent where balance is important, such as when rock scrambling, skiing, and hiking over rough, steep terrain. A disadvantage of this is that you tend to lean forward to counterbalance the low weight. Careful packing with heavy items high up and close to the back is a partial answer when you are walking on a good trail but is no panacea if the pack is poorly designed (see Packing later in this chapter).

On many packs, the stays are removable; this is one way to lighten the pack for a side trip or an ultralight trip. In snow, the stays could be used as tent stakes or even an emergency snow saw.

Crude internal frames can be created for frameless packs with a foam pad by folding it to fit down the back of the pack or rolling it up, placing it in the pack, and allowing it to unroll. Pads take up a fair amount of room, however, and can still distort under heavy loads; I think 30 pounds is the upper limit. Some packs, like the Gossamer Gear models mentioned, are designed with sleeves in the back to use foam pads as frames; the pad takes up no room inside the pack. The best design I’ve seen like this is the ULA Fusion, which has a carbon fiber–composite rod hoop running around the edges of the back and a large, foam back panel. Your sleeping pad fits behind this panel and the pack itself and is held in place by straps, creating a much firmer support than usual with a pad. The Fusion is new (as of 2004) so I haven’t used it much yet, but it looks like it will become a personal favorite.

Your back and shoulders are not designed for bearing heavy loads. In fact, the human spine easily compresses under a heavy weight—one reason back injuries are so prevalent. Furthermore, when you carry a load on your shoulders, you bend forward to counterbalance the backward pull of the load. This is uncomfortable and bad for your back, and the pressure on sensitive muscles and nerves can make your shoulders ache and go numb.

The solution is to lower the load to the hips, a far stronger part of the body. The hipbelt is by far the most important part of any pack suspension system designed for carrying loads of more than 20 to 25 pounds. It’s the part of the pack I always examine first. A well-fitting, well-padded hipbelt transfers most of the pack weight from the shoulders onto the hips, allowing the backpacker to stand upright and carry a properly balanced load in comfort for hours. Some ultralight packs don’t have hipbelts—indeed, some ultralight hikers seem to regard hipbelts as demonic symbols of submission to advertising hype. They argue that they are unnecessary with ultralight loads and restrict freedom of movement. Having tried hiking with the GoLite Breeze, which doesn’t have a hipbelt, I can’t agree. Even with less than 20 pounds in the pack, my shoulders could feel the weight by the end of the day, and I found not having a belt restrictive. Stability was poorer, too. Even with very light loads I like a hipbelt, though for loads under 30 pounds it doesn’t need to be big and bulky or even have any padding at all.

The first hipbelts were unpadded webbing. On some ultralight packs they still are, but most of today’s hipbelts are complex, multilayered creations of nylon, foam, plastic, and even graphite. A good hipbelt should be well padded with soft, thick foam that molds around your hips. Those designed for loads of more than 40 pounds should also have some form of stiffening to prevent twisting when loaded. This may be an outer layer of firm foam or stiff but flexible polypropylene or polyethylene plates. Many belts are made from thermal-molded foam that forms a belt with a firm conical shape that hugs the body without sagging.

As always, somebody disagrees with the prevailing wisdom. McHale, a custom pack maker in Seattle, claims stiff belts are uncomfortable and unnecessary; its soft belts, McHale says, made from Evazote foam with double buckles, wrap round the hips so well that they create their own firm structure. They are continuous, attached to the pack only at the bottom edge, and run outside the lumbar pad so they wrap around the body and mold to your shape. I haven’t used a McHale hipbelt, but they look interesting. I haven’t found any problems with conventional, stiffened belts, though.

In addition to being thickly padded, a hipbelt should be at least 4 inches wide where it passes over the hips, narrowing toward the buckle. Conical or cupped belts are less likely than straight-cut ones to slip down over the hips (though most belts eventually slip with ridiculously heavy loads, whatever the shape); most belts on top-quality packs designed for heavy loads are shaped. For the heaviest loads, continuous wraparound belts perform better than those sewn to the side of the pack; again, most top models have these. To support the small of your back, the lower section of the pack should be well padded. This can be a continuation of the hipbelt (as in most external-frame packs), a special lumbar pad (as in most internal frames), or part of a completely padded back. The lumbar pad is important for supporting the load and spreading the weight over your lower back and hips. A too-stiff or too-soft lumbar pad can lead to pressure points and sore spots. Continuous hipbelts run behind the lumbar pad and may be attached to it with Velcro.

Belts that are attached to the frame or the lumbar pad only at or near the small of the back need side stabilizer or side tension straps (also called hip tension straps) to prevent the pack from swaying. These straps pull the edges of the pack in around the hips, which increases stability. Most internal-frame packs have them. A few models also have diagonal compression straps, which run downward across the side of the pack to the hipbelt and help pull the load onto the hipbelt. These work well.

Many hipbelts are nylon-covered inside and out. Although adequate, a smooth covering like this can make the belt slip when it’s worn over smooth synthetic clothing, a problem that worsens as the load increases. Cordura or other texturized nylon is better; some companies use special high-friction fabrics. These may cover the whole inside of the belt or just the center of the lumbar pad.

Most hipbelt buckles are the three-pronged Fastex type or something similar. These are tough and easy to use, but they can break if you step on them, so be careful when the pack is on the ground. Carrying a spare on long trips, or putting one in a supply box, is a good idea. I had a buckle break at the start of a two-week winter trip. How, I’m not sure, though I suspect baggage handlers even though the pack was in a duffel bag. I didn’t have a spare, and I was very glad that the mountain hut where I spent the first night sold them. Otherwise I’d have had to go out to a town to get one, since carrying a heavy winter load without a hipbelt was unthinkable. There are a few other buckle types around, such as the cam-lock buckles McHale uses.

Hipbelt size is important. The padded part of the belt should extend at least 2.5 inches in front of the hipbone, and after you tighten the belt there should be enough webbing left on either side of the buckle to allow for weight loss on a long hike and for adjustment over different thicknesses of clothing. Some packs come with permanent hipbelts, so you have to check the size when you buy. Packs that come in two or three sizes often have belts sized to the frame length (e.g., medium frame, medium belt), which is fine unless you are tall and thin or short and stout. Companies that make packs with removable belts often offer a choice of belt sizes. Such modular systems are the best way to achieve the optimum fit, especially if you’re not an “average” size. Gregory, for example, makes hipbelts in four sizes—small, 22 to 28 inches; medium, 28 to 34 inches; large, 34 to 40 inches; and extra large, 40+ inches. My waist (measured around the top of the iliac crest, not the stomach) averages 34 inches (occasionally less, sometimes more), so I have a medium belt on my Gregory Shasta. There are different hipbelts for men and women, too, though since everyone is a different shape, it may be that one labeled for the opposite sex fits best. Keep an open mind! Rather than have belts for each gender, some makers, such as Gregory, have belts whose angle over the hips can be altered so it follows your shape.

How big a belt you need depends on the weight you intend to carry. The basic principle is simple: big loads need big belts. I’ve found that moderately padded belts handle loads up to 45 pounds adequately. Heavier loads, however, cause these belts to compress and press painfully on the hip-bones or else twist out of shape, making it difficult to put most of the load on the hips. For heavy loads, wide hipbelts with thick layers of padding and stiffened flexible reinforcements on the outside are best. My favorite for many years has been the Dana Design Contour Hipbelt, a massive thick, stiffened belt. I’ve carried loads of 60 pounds or more for weeks at a time using this belt and never had bruised or sore hips. I’m also impressed with the Arc’teryx Bora hipbelt, made from four layers of laminated, thermo-formed foam in a curved, cupped shape that fits neatly around my hips.

Finally, consider what you wear under a hipbelt as well, because this will be pressed against your skin. Pants with thick side seams, belt loops, rivets, and zippered pockets can rub painfully. Wide, elasticized waistbands or bib styles are better. If you do find a sore point under a hipbelt, check to see if it’s caused by your clothing before you curse the pack.

Most of the time, shoulder straps do little more than stop the pack from falling off your back. But because there are times when you have to carry all or some of the weight on your shoulders (for example, river crossings when you’ve undone the hipbelt for safety and rock scrambles and downhill ski runs where for balance you’ve fully tightened all the straps to split the weight between shoulders and hips), these straps need to be foam-filled and tapered to keep the padding from slipping. This design is now standard on most good packs. Many straps are also curved so they run neatly under the arms without twisting. The key to a good fit is the distance between the shoulder straps at the top. Some straps are adjustable here so they will fit both broad and narrow shoulders. A few, like those on Gregory packs, adjust automatically. There are different shoulder straps for men and women, too. As with hipbelts, this isn’t a strict division, however. Shoulder straps also come in different lengths—Gregory offers three for men and three for women, for example. Usually the length that corresponds to the frame length will fit, but if it doesn’t you can change it for a different one.

Packs designed for moderate to heavy loads (30 pounds and up) should have load-lifter straps (sometimes called top tension, load-balancing, or shoulder stabilizer straps) running from the top of the shoulder straps to the pack. These straps pull the load in over your shoulders to increase stability; they also stop you from feeling that the pack is falling backward and lift the shoulder straps off the sensitive nerves on top of the shoulders, transferring the weight to the collarbone. By loosening or tightening the straps, which you can do while walking, you can shift the weight of the pack between the hips and the shoulders to find the most comfortable position for the terrain you’re on. Take a little time to adjust both the shoulder and load-lifter straps until the pack feels comfortable and stable. To work well, the straps need to rise off the front of the shoulders at about 45 degrees.

On most packs, the load-lifter straps are sewn to the shoulder straps, which means that altering the tension of one changes the other; so when you tighten the load-lifter straps for better stability, you also pull the shoulder straps down onto your shoulders. If they then feel too tight, you slacken them off, which also loosens the load-lifter straps and causes the pack to fall backward. To maintain stability, you tighten the load-lifter straps again. Repeating the cycle over and over can mean that by the end of the day the top tension straps are at their minimum length and therefore not as effective as they should be, while the shoulder straps have crept down your back and their buckles are pinching your armpits. I always try to get the adjustment about right at the start of the day and keep any alterations to a minimum. Even so, I end some days with a pack that is very badly adjusted. Though I haven’t tried it, McHale seems to have found a simple solution with the Bypass shoulder system, in which the stabilizer straps aren’t sewn to the shoulder straps. This means that the shoulder straps can slide along the stabilizers when they’re adjusted without the latter’s moving at all. The Bypass shoulder system has been around for a while, and I fully expected other makers to come up with their own versions. They haven’t, however, presumably because they believe the conventional one works.

Sternum straps are found on most packs, attached to buckles or webbing on the shoulder straps. They pull the shoulder straps in toward the chest and help stabilize the pack. I don’t use them much of the time, since they feel restrictive, but they can be helpful for stability when skiing or scrambling and for varying the pressure points of a heavy load during a long ascent. Most are simple webbing straps, but some have stretch sections that prevent over-tightening. Fully elasticized straps can’t be tightened at all and are useless. The position of sternum straps is important. They should sit high up, just below your neck, to reduce pressure on your chest.

In addition to a padded hipbelt and lumbar pad, most internal-frame packs have padded backs, some of them cushy panels of thermo-molded foam. If the entire back isn’t padded, then the padding on the shoulder straps should run far enough down the back to protect the shoulder blades. Since much of the pack never touches the wearer’s back directly, some of the padding is often unnecessary; too little, though, and sharp objects can poke you. Open-weave mesh over the foam helps moisture to disperse so your back doesn’t get quite as sweaty as with plain nylon.

External frames need something to hold the crossbars off your back. On basic packs this is usually a wide band of tensioned nylon; mesh is better for ventilation than solid nylon. The tensioning cord or wire should be easy to tighten if it works loose. More expensive models sometimes have a pad of molded foam instead. The latter may be more comfortable, but it also reduces ventilation, lessening one of the advantages of external frames.

Modern packs are so complex that you can’t just walk into a store, sling one on your back, and walk away. A good pack must be fitted, and it is important that this be done properly. A poorly fitted pack will prove unstable, uncomfortable, and so painful and inefficient that you may never want to go backpacking again. The best way to avoid this is to buy from a store with expert staff who can fit the pack for you. Allow plenty of time for this; it can take a while to get it right.

If you don’t want to bother taking time to fit a pack—some people think having to do so means the pack is too complicated—a simple rucksack or a traditional external-frame pack would be the best choice. Even with these designs, you need to find the correct back length, though a precise fit isn’t essential. A pack whose shoulder straps join the pack roughly level with your shoulders when the hipbelt, if there is one, is taking most of the weight comfortably on your hips should be fine. The first task in fitting a pack is to find the right back length. Your height is irrelevant here. The length of your legs, neck, or head makes no difference to the size of pack that will fit your back. I’m 5 feet, 8 inches tall, but I have a long torso. If I went by my height, as some pack makers still suggest, I’d end up with a pack that was too short. If a pack is too long, it will tower over your head and be very unstable; if it’s too short, the hipbelt will ride above your hips and won’t be able to take much weight.

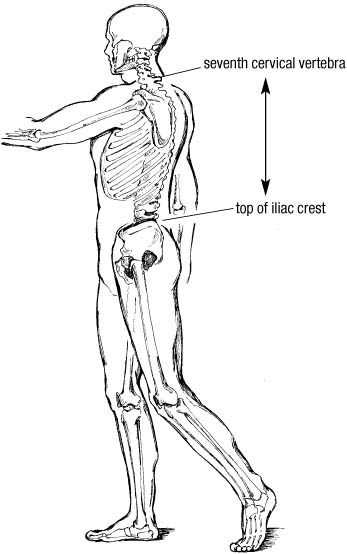

The key measurement for finding the right size is the distance from the base of your neck to your upper hipbone, technically from the seventh cervical vertebra (a clearly felt knob) to the top of the iliac crest, which you can find by digging your thumbs into your sides. You can measure this yourself with a flexible tape measure, but it’s much easier to get someone else to do it. Most frames come in two to five sizes. Dana Design’s Arcflex packs, for example, come in five lengths—extra small, 14 to 16 inches; small, 16 to 18 inches; medium, 18 to 20 inches; large, 20 to 22 inches; and extra large, 22 to 24 inches. My back measures 19.5 inches, so I have a medium Arcflex pack. However, I bought my Dana Design Astralplane by mail order and got the size wrong the first time, buying a large. The company quickly exchanged my pack, and the Arcflex is the most comfortable suspension system I’ve used.

How to correctly measure the back for pack fitting.

Not all pack makers use the same back lengths for their sizes, though the variation is small; it partly depends on how many sizes they make. ULA P-1 and P-2 packs come in four sizes—small, 15 to 17 inches; medium, 18 to 20 inches; large, 21 to 23 inches; and extra large, 23 inches plus. Again I’m a medium, so that’s the size of my ULA P-2. If you’re on the edge of two sizes, try on both and see which feels better.

When you have the right back length, check that the hipbelt and the shoulder straps are the correct sizes (see pages 105–7). The hipbelt should ride with its upper edge about an inch above your hipbone, so that the weight is borne by the broadest, strongest part of your hips. The top of the frame, if there is one, should then be 2 to 4 inches above your shoulders so that the load-lifter straps rise at an angle of about 45 degrees. Most pack makers tell you how to measure your back length and which of their sizes go with which back lengths. Some, like Gregory, provide stores with a fitting tool that makes finding the right size easy. All packs come with instructions for fine-tuning the fit, some more detailed than others. Instructions differ according to the specifications of the suspension system, but there are some general principles.

Once you have the right back length, it’s time to fine-tune the pack for the greatest comfort. The most common way to do this is with an adjustable harness, which allows you to move the shoulder straps up and down the back of the pack. On a few packs the positions of both the shoulder straps and the hipbelt are adjustable. However, hipbelt adjustments change the position of the base of the pack in relation to your body, which causes the load to press on your backside when the effective back length is shortened and to ride too high on the back when it’s lengthened. Both interfere with stability and comfort, so any hipbelt position adjustments should be very fine. I’ve found that the best position is with the base of the hipbelt level with the base of the pack.

Lowe Alpine was first with an adjustable shoulder harness system. In its much-copied Parallux system, the shoulder straps are fitted into slots in a webbing column sewn down the center of the pack’s back. Variations employ Velcro straps or a slotted plastic adjustment “ladder.” Others have plastic plates that attach to each other with Velcro. These systems demand some fiddling; easier are stepless systems that use a locking slider, screw, or similar device to slide the shoulder straps up and down the central column. Even simpler are systems in which the shoulder straps are attached to a stiffened plastic yoke that slides up and down the stays; you can adjust these while wearing the pack by simply pulling on two straps attached to the base of the plate. Some adjustment systems are easy to use; others are hidden under back padding and can be hard to find, let alone use. Losing your temper doesn’t help, as I know from experience. Instruction manuals aren’t always much use either. Help from knowledgeable sales staff is the best bet. Whichever type you end up with, find the right position for your back and then forget about it. Obviously, any system has a limited adjustment range. At either end of this range a pack won’t carry as well as it does if adjusted to a position nearer the middle. Packs that come in just one frame size will still fit only a narrow range of back lengths, however adjustable they are.

Adjustable harness systems.

Before you try on a pack, load it with at least 25 to 30 pounds of gear. An empty or lightly loaded pack is impossible to fit properly and will of course feel fine. Most stores will fill the pack for you—sometimes with ropes—though you could take your own gear to check that it fits in the pack properly. Before putting on the pack, loosen all the adjustment straps. Then put the pack on and do up the hipbelt until it is carrying all the weight and the upper edge rides about an inch above the top of your hipbone. Next, tighten the hipbelt stabilizer straps, followed by the shoulder straps and load-lifter straps. The last should leave the shoulder straps at a point roughly level with your collarbone or just in front of it, at an angle of about 45 degrees. If the angle is smaller than that, the harness needs lengthening or the pack is too short; if it is larger, it needs shortening or the pack is too long. The aim is to have most of the pack weight riding on the hips while the pack hugs the back to provide stability. If the distance between the shoulder straps and hipbelt is too short, the load will pull back and down on the shoulders; if it’s too long, although the weight will be on the hips, the top of the pack will be unstable and will sway when you walk. (See photos next page.)

Once you have the right size pack and have adjusted the harness correctly, most of your fitting problems are over. The shoulder straps themselves should curve over your shoulders a couple of inches before joining the pack. They shouldn’t feel as though they are slipping off your shoulders or be so close together that they pinch your neck. The lower buckles should be several inches below the armpits so they don’t touch you, but with enough webbing to allow for adjustment over different thicknesses of clothing.

Finally, make sure the sternum strap is in the correct position, above the part of your chest that expands most when you breathe but not so high that it presses on your neck. When you walk, the pack should hug your body as if it’s stuck to you. If it feels awkward or uncomfortable, keep adjusting until you get it right or until you decide that this particular pack will never fit you comfortably.

Once I have the best fit I can obtain with an internal-frame pack, I usually bend over and stretch the pack on my back so the frame can start to mold to my shape, a process that is usually complete after the first day’s walk. Some pack makers advise removing the stays of internal frames and bending them to the shape of your back before you start fitting the pack, but I’ve never been able to do this successfully, even with help from a friend, and prebent stays are the devil to reinsert in their sleeves. Some stores have staff trained to do this for you. However, a friend suggests that “the trick is to make lots of very fine adjustments, and to make each one by bending [the stays] around gentle curves such as one’s upper thigh.”

You have to make minute adjustments to the harness every time you use a pack. Loosening the top stabilizer straps, tightening the shoulder straps, then retightening the stabilizers cinches the pack to the body for maximum stability but also shifts some of the load onto the shoulders. This is useful on steep descents or when skiing or crossing rough ground—anywhere balance is essential. For straightforward ascents and walking on the flat, the shoulder and stabilizer straps can be slackened off a touch so that almost all of the weight drops onto the hips, then the stabilizers should be tightened a little again until you can just slide a finger between the shoulder and the shoulder straps.

Altering the back length of an adjustable backpack (Vaude Astra 65 II).

Adjusting the side tension straps.

Tightening the load-lifter straps.

Every time you put on the pack, you have to loosen the side stabilizer straps, then tighten them after you’ve done up the hipbelt—otherwise the latter won’t wrap around the hips properly. While you’re on the move, whenever the pack doesn’t feel quite right or you can feel a pressure point developing, adjust the straps to shift the balance of the load slightly until it feels right again. I do this frequently during the day, almost without noticing it.

If you want or need a custom fit, McHale, which sells through its own store in Seattle and its Web site, will make a pack to your measurements. If you always seem to be between sizes with fixed-length packs or at the ends of the adjustment systems of adjustable ones, a McHale pack might be the answer.

Although makers don’t usually say so, packs that don’t come labeled as “men’s” or “women’s” are usually designed for the “average” man. But women often have shorter torsos, narrower shoulders, and wider hips than men do. This means men’s packs may have frames that are too long (leading to an unstable carry and too much weight on the shoulders), overly wide shoulder straps that slide off and have to be held in place by a tight sternum strap, and hipbelts that dig in at the lower edge and don’t touch at the top.

The past twenty years have seen a big change, with many packs now specifically designed for women. Modular packs for which you can select different hipbelts and shoulder straps are an alternative. We’re all different, so being able to choose components that fit your shape or else to vary the fit of those that come with the pack means everyone should be able to find a pack that fits well.

Compared with the intricacies of frames and suspension systems, packbag design is straightforward. The choice is purely personal—the type of packbag has little effect on the comfort of your pack. How many pockets, compartments, and external attachment points you want depends on how you like to pack and the bulk of your gear. Tidy folk like packs with plenty of pockets and at least two compartments so they can organize their gear. Those who are less neat tend to go for large, single-compartment monsters so they can shove everything in quickly.

There are a couple of points to consider, however. To maintain balance and comfortable posture, the load needs to be as close as possible to your center of gravity. This means keeping it near your back and as high up as is feasible without reducing stability. While a good suspension system is the key to this, it helps if the packbag extends upward and perhaps out at the sides but not away from the back. For this reason, if your pack has large rear pockets, you should pack only light items in them. My Dana Design Astralplane has such pockets. I find that if I pack them with light items such as hats, gloves, and windshirts they don’t affect the carry, but if I put full water bottles in them I can feel the pack pulling backward. Many packs have a strap at the top running from front to back across the packbag. When tightened, this strap pulls the load in toward the back. They work well, and I look for one on a large pack.

The packbag is an integral part of an internal-frame pack. The frame may be embedded in a foam-padded back, encased in sleeves, or just attached at the top and bottom of the bag. Whatever the method, the frame and pack work together and cannot be used separately. Packbags may be attached to external frames in various ways, but the most common is with clevis pins and split rings. One frame conceivably could be used with several different packbags or with other items such as stuff sacks.

How large a packbag you need depends on the bulk of your gear, the length of your trips, and how neatly you pack. I’ve always preferred large packs. I like to pack everything inside (including my insulating mat when possible), and I like to know I can cram everything in quickly and easily, even in the dark after the tent has just blown down in a storm. (Paranoia? Maybe, but it has happened to me.) Those who favor small packs say that a large pack is a heavy pack because you’ll always fill it up. I say this applies only to the weak willed! If I had only one pack, it would be a large one. A large pack cinched down when half full is far more comfortable than an overloaded small one.

Now that there is lighter, more compact gear, I generally use a smaller pack. A pack of 4,000 cubic inches or so is now enough for most three-season trips, however long. I still use a 7,200-cubic-inch monster for cold-weather trips, but it doesn’t get as much use as it did, and my 5,500-cubic-inch pack hasn’t been used for a few years, being too small for the cold-weather trips but too big and heavy for the rest of the year.

A minor problem is that different manufacturers seem to have different ideas of what constitutes a cubic inch, so one maker’s 5,000-cubic-inch pack may hold less than another’s 4,500-cubic-inch model. (GoLite and some other top makers use a standard approved by the American Society for Testing Materials. If every maker used it, the problem would disappear.) When choosing a pack, think about whether your gear will all fit in with room left for food. You could even take your gear to the store and pack the sack to be sure.

Internal-frame packs usually have compression straps on the sides or front that you can pull in to hold the load close to the back when the pack isn’t full. Traditional external-frame packs lack these, though they do appear on some new designs. Packs with compression straps and removable extendable lids are often specified with maximum and minimum capacities; to achieve maximum volume, you may have to raise the lid so high that the top of the pack becomes unstable, so it’s wise to check this before you buy.

External-frame packbags that run the length of the frame tend to be very large. The more common three-quarter-length bags can have capacities as small as 2,500 cubic inches, though most average about 4,000 cubic inches. Extra gear (sleeping mat, tent, sleeping bag) can be strapped under the packbag without affecting how the pack carries, and if necessary, even more gear can be lashed on top. However, if you strap extra gear, other than light items like foam pads, under or above an internal-frame pack, you might ruin its balance and fit. If you need to carry a really awkward load, you can remove the packbag from an external frame and strap the load directly to the frame.

Most large packs come with zippered lower compartments, though you can get packs with one huge compartment. Compartments with long zippers that run right around the packbag or curve down to the lower edges are the easiest to use. With large packs—5,000 cubic inches or more—I prefer two compartments because they provide better access to my load. On most packs the divider separating the two compartments is held in place by a zipper or drawcord and can be removed to create a single compartment if needed. A few pack makers offer packs with more than two compartments. I suspect this might make packing difficult. I’m not that organized! With smaller packs I find a single compartment adequate. Not having the divider or zipper saves a little weight and expense, too.

Lids keep the contents of your pack in, prevent things from moving around, and protect the pack opening from rain. Most packbags have large lids, sometimes with elasticized edges for a trimmer fit, that close with two straps fastened by quick-release buckles. Ultralight packs often have no lid at all, just a rollover top that closes with buckles or a couple of drawcords and a buckle and strap.

Many packbags have a floating lid that attaches to the back of the pack by straps and can be extended upward over a large load or tightened down over a small one. These lids can be removed when not needed to save weight. A similar, though less effective, design is a lid that is sewn to the back of the packbag but extends when you release the straps at the back. When such a lid is fully extended, it tends to restrict head movement, interferes with easy access to the lid pocket, and fails to cover the load. Many detachable lids contain large pockets (500+ cubic inches) and can be used as lumbar packs or even small day packs by rearranging the straps, using extras provided for that purpose or by using the pack hipbelt. They can be useful for carrying odds and ends (film, hat, gloves, binoculars) on short strolls. I’ve used a detachable pack lid as a day pack for daylong hikes away from camp, managing to pack in rain gear, warm clothing, and other essentials.

The lower compartments of packs are always closed by zippers. Straps that run over the zipper take some of the strain and reduce the likelihood of its bursting. Since I’ve had problems with lightweight zippers on day packs, I like large zippers, whether toothed or coiled; lightweight zippers, protected by straps or not, worry me. Top compartments usually close with two drawcords, one around the main body of the pack, which holds the load in, and one on the lighter-weight extension, which completely covers the load when pulled in. If the only access to the load is through the top opening, items packed at the bottom of the top compartment cannot be reached easily. Vertical or diagonal zippers in the main body are found on some large packbags. I find these useful, especially in bad weather, when I can extract the tent, including the poles, through the open zipper without unpacking other gear, opening the main lid, or letting in much rain or snow.

Zip-around front panels for suitcase-type loading, giving easy access to the whole interior of the packbag, have fallen out of popularity, probably because the pack had to be laid down to pack and unpack—not a good idea in the rain or on mud or snow. The pack couldn’t be pulled tight around a partial load, either, so items would move around. Panel loading is now primarily found on travel packs.

Some large packs, however, have both top- and panel-loading main compartments. This has the advantages of both and is an alternative to the main-compartment zippers. I look for one or the other in any pack of more than 5,000-cubic-inch capacity.

Pockets are useful for stowing small, easily mislaid items and things you may need during the day. Lid pockets are found on most packs except traditional external-frame models and some of the newer lightweight packs. The best lid pockets are large and have either curved zippers or zippers that run around the sides for easy access. Some packs also have a second flat security pocket inside the lid for storing documents, wallets, permits, and similar items.

External-frame packs normally come with one, two, or (rarely) three fixed pockets on each side. Internal-frame packs, often designed for mountaineering as well as backpacking, don’t usually have fixed side pockets, since these can get in the way when climbing. Instead, optional detachable pockets can be fastened to the compression straps. These add 500 to 1,000 cubic inches per pair to the pack’s capacity and 4 to 12 ounces to the weight. They can be removed to reduce the capacity of the pack or when using the pack for skiing or scrambling, when side pockets are a nuisance. Some side pockets have backs stiffened with a synthetic plate, which makes them slightly easier to pack but also heavier. A few makers also offer large pockets that can be attached to the back of a pack.

An alternative to a detachable pocket is an integral bellows side pocket with side-zipper entry, which folds flat when not used. I find bellows pockets more difficult to use than detachable pockets. They are narrow at the top and bottom, can be obstructed by compression straps, and when full can impinge on the volume of the main compartment. And you still have to carry the weight of the material when you don’t need the pockets. On the other hand, they are always there when you need them—you can’t forget one.

Many packs have open pockets at the base of each side. These wand pockets were originally designed to hold the thin wands that mountaineers use to mark routes and caches on glaciers and snowfields. They are useful for supporting the ends of long, thin items such as tent poles, trekking poles, or skis. Wand pockets are usually permanently attached, though some, like those from McHale, are detachable and can be replaced with a larger open pocket that will hold a quart or liter water bottle. Some wand pockets have elasticized edges and can be stretched to take a small water bottle. I often carry a map in the wand pocket for easy access.

With the new ultralight packs came ultralight pockets made from rugged mesh. These may have open tops with drawcord closures or else zippers. They are now my favorite pockets. You can stuff wet gear into them—tarps, flysheets, rain clothing—and it will slowly drain and dry and not soak other items. The side pockets can hold water bottles so you can reach them while wearing the pack. You can also use them for snacks, a toilet trowel, fuel bottles, and other items you want to have outside the main pack. Detachable mesh pockets are sold, so you can add them if your pack doesn’t have them.

I also like pockets on the hipbelt. I have these on my ULA P-2 pack, and they are great for a compass, a whistle, snack bars, and other small items.

Many packs have internal hydration sleeves or pockets designed to hold water bladders, with an exit hole for the drinking tube. If you use a hydration system, these are useful—though you can just put the bladder in an external pocket—otherwise they can be used for storing items like maps and small items of clothing.

Side compression straps can be used to attach skis and other long items (trekking poles, tripods, tent poles, foam pads). Most packbags come with one or two sets of straps for ice axes and straps (and maybe a reinforced panel) for crampons on the lid or the front. If straps don’t come with the pack, there are often patches so you can thread your own. Many packs come with far too many exterior fastenings, but you can always cut off those you’ll never use.

Modern packs are made from a variety of coated nylons and polyesters. These fabrics are hardwearing, nonabsorbent, and flexible. Texturized nylons—made from a bulked filament that creates a durable, abrasion-resistant fabric—are often used for the pack base or bottom, sometimes with a layer of lighter nylon inside; some makers use this fabric for the whole packbag. The most common is Cordura, though a few companies have their own proprietary fabrics. Packcloth is a smoother, lighter nylon often used for the main body of the pack. All of these materials are strong and long-lasting.

One way to keep the weight of a pack down is to use lightweight fabrics. Packcloth and 500-denier Cordura are lighter than 1,000-denier Cordura, but not by enough to make a big difference in weight. (The denier is the weight in grams of 9,000 meters of yarn. Thus 500-denier Cordura is made from yarns that weigh 500 grams per 9,000 meters. The lower the denier, the finer the yarn.) There are some really lightweight fabrics, though. For ultralight packs where weight is more important than durability, ripstop nylon is sometimes used. Silicone ripstop nylon is the strongest lightweight nylon and companies like GoLite use it in packs like the Speed (32 ounces, 3,400 cubic inches). DSM’s Dyneema and Honeywell’s Spectra cloth are very light polyethylene fibers that are ten times stronger than steel, pound for pound, more durable than polyester, and very abrasion- and ultraviolet resistant. Kelty’s 5,250-cubic-inch internal-frame Spectra pack, the Cloud, weighs 71 ounces, while McHale’s 3,500-cubic-inch internal-frame pack, the Spectra SUBPOP, weighs 39 ounces.

Unfortunately, there are penalties for these low weights. These fibers are very expensive and come only in white and gray—they can’t be dyed. However, they can be woven with ordinary nylon to produce a fabric with ripstop threads made from polyethylene fibers filled in with nylon. This produces a colored fabric with a white grid imposed on it that looks far less conspicuous than pure Spectra or Dyneema and also costs less. It’s used in many lightweight packs from companies like GoLite, McHale, and ULA and is very tough. I’ve used Spectra and Dyneema gridstop packs extensively, including on a five-week hike, and haven’t yet damaged the fabric. Even airport baggage handlers have failed to harm it—and in the interests of testing, one pack has been through several airports unprotected. I now consider these the best fabrics for packs.

While most of these fabrics are waterproof when new, the coating that makes them so is usually soon abraded. The seams will leak in heavy rain anyway. Some manufacturers advise coating the seams with sealant, but the process is too complicated and messy for me to even contemplate. I rely on liners and covers (see pages 125–26) to keep the contents of the pack dry.

For many years I used a large, heavy pack for all my backpacking on the rationale that the pack was the one item of gear whose weight wasn’t significant because comfort came first. I’m less convinced about the weight now. Comfort still comes first, and for loads of 50 pounds or more, a pack with a sophisticated suspension system is certainly far more comfortable than one with a more basic design, despite the extra weight. With loads over 30 pounds, I still find a framed pack more comfortable than a frameless one, but it doesn’t have to be heavy. For loads under 30 pounds, ultralight packs without frames can be perfectly comfortable. Comfort doesn’t have to equal weight anymore. Indeed, a lighter pack means a lighter load, which means your legs get less tired.

Despite the increasing number of lightweight and ultralight packs, most packs are still pretty heavy, weighing at least a pound for every 1,000 cubic inches of capacity—about 62 cubic inches per ounce. Many packs are heavier, with as few as 45 cubic inches per ounce. Yet a standard 6,000-cubic-inch internal-frame pack I have that dates back to 1982 weighs less than 5 pounds, giving 77 cubic inches per ounce.

For two decades—right up until the late 1990s—the weight of packs kept increasing. More complex frames, thicker padding, heavier fabrics—which most packs are still made from—detachable pockets, detachable lids, more straps, zippers, and buckles all piled on the weight. Eventually there had to be a reaction. Other gear—tents, sleeping bags, stoves, clothing, footwear—had gotten lighter. The change came with the increased popularity of long-distance hiking and the rise of adventure racing. Fast movers and light hikers didn’t want heavy packs, so lighter models began to appear on the market. The old heavyweights still dominate, but for light loads there’s no longer any need to carry a heavy pack.

A good rule of thumb for estimating pack weight is that the pack shouldn’t weigh more than 10 percent of the maximum total load: for a 70-pound winter load, a 7-pound pack is acceptable, but for a 30-pound summer load, a 3-pound pack would be better. Of course, if you use the same pack year-round, as many backpackers do, the 7-pound pack would carry the 30-pound load. Another way of thinking about pack weights comes from ULA, which suggests that a lightweight pack should be able to support in pounds the same figure as its weight in ounces. Thus my 40-ounce ULA P-2 pack should be comfortable with 40 pounds, which it is. ULA also says that an ultralight pack should support in pounds 150 percent of its weight in ounces. Thus, at 14 ounces, the GoLite Breeze should support 21 pounds, which it will do—just barely.

Acceptable weight can also be roughly determined by the volume-to-weight ratio, found by dividing the capacity by the weight in ounces. Since the average ratio for most modern packs is 60 to 65 cubic inches per ounce, any figure lower than this means the pack is heavy for its capacity (the Astralplane comes in at 58 cubic inches per ounce), and any higher figure means it’s lightweight. Quite a few packs that should be fine with light to moderate loads come in the range of 70 to 90 cubic inches per ounce. Some are even lighter. The ULA P-2 has 100 cubic inches per ounce, the GoLite Gust an astonishing 192 cubic inches, the GoLite Breeze 206 cubic inches, and the Gossamer Gear G4 285 cubic inches.

I still regard comfort as the crucial factor for carrying loads. When you’re lugging 60 pounds or more, a pound or two of additional pack weight is worth it if you get a more comfortable carry. But for lighter loads, especially those under 40 pounds, I now like packs with a volume-to-weight ratio of at least 100 cubic inches per ounce.

Top-quality packs are very tough, but many won’t last for a walk of several months. I’ve suffered broken internal frames, snapped shoulder straps, ripped-out hipbelts, slipping buckles, and collapsed hipbelt padding on long hikes. On my first long solo hike back in 1976, the hipbelt tore off my new external-frame pack after just 200 miles. But I’ve also had packs last 2,000 miles and four and a half months of continuous use with loads averaging 60 to 70 pounds. My old Gregory Cassin, a discontinued model, survived a three-month Yukon walk with a heavy load when it was five years old and had already had many months of use. The only damage was to the top of one framestay sleeve, which ripped out. (Duct tape held it in place for the rest of the walk.) This degree of use is comparable to years, if not decades, of backpacking for those who go out for several weekends a month and perhaps a couple of two- or three-week trips a year.

Of the three people I know who hiked all or most of the Pacific Crest Trail the same year I did, each broke at least one pack. After months of constant use and harsh treatment, it seems that something is almost bound to fail, considering how complex a modern pack is and how much can go wrong. The heavier the load, the more strain on the pack—another reason for keeping the weight down.

Crude repairs can, and often must, be made to equipment in the field, but I’m loath to continue backpacking in remote country with a pack that has begun to show signs of failing, at least not before it’s had a factory overhaul. After replacing broken packs at great expense in both time and money on my Pacific Crest Trail and Continental Divide walks, I had a spare pack ready and waiting when I set off on a Canadian Rockies through-hike. On that walk I replaced my pack early because it wasn’t able to carry the weight (the makers had changed the style of the hipbelt from earlier models). The replacement pack broke two weeks before the end of the trek, and I had to nurse it to the finish, bandaged with tape. Perhaps I’m unlucky or particularly hard on packs, but for future lengthy ventures I plan to have a spare pack, and I’d advise anyone else to do the same.

Reputable pack makers stand behind their products, and most will replace or repair packs quickly if you explain the situation, though that isn’t much comfort if you’re days away from the nearest phone when your pack fails. Even a spare pack is no good until you can pick it up. It’s important to be able to effect basic repairs; in Chapter 8, I cover the items to carry in a repair kit.

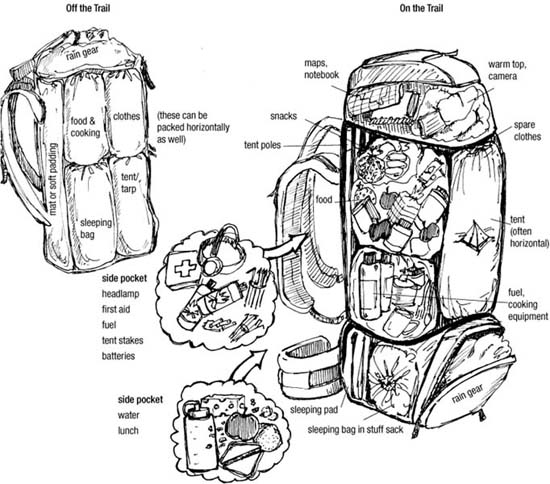

How you pack gear depends on the sort of hiking you’re doing, which items you’re likely to need during the day, and the type of packbag you have. For hiking on level ground on well-maintained trails, heavy, low-bulk items should be packed high and near to your back to keep the load close to your center of gravity and enable you to maintain an upright stance. This is how I pack all the time, regardless of the terrain. In theory, however, for any activity where balance is important, such as scrambling, bushwhacking, cross-country hiking on steep, rough ground, or skiing, the heavy, low-bulk items should be packed lower for better stability, though still as close to your back as possible. Women tend to have a lower center of gravity than men and may find packing like this leads to a more comfortable carry for trail hiking too. Whatever your packing method, it’s important that the load is balanced so the pack doesn’t pull to one side. The items you’ll need during the day should be accessible, and it helps to know where everything is.

I normally use a packbag with side or rear pockets and, with heavy loads, a lid pocket, so my packing system is based on this design. I don’t like anything on the outside except winter hardware (ice ax and skis) and a closed-cell sleeping mat; everything else goes inside, and I pack most items in stuff sacks to keep everything organized.

With ultralight packs with no back padding, a sleeping pad can be used to cushion your back. Standard foam pads can be placed vertically in the pack and then unrolled so you can pack gear in the middle of the pad. A Z-Rest pad (see page 237) can be folded flat and put down the back of the pack, as can a self-inflating mat. All these are effective but do take up a fair amount of the capacity of the pack. If you don’t use a pad, gear can be packed into two long stuff sacks that you stand vertically side by side in the pack. Make sure there are soft items next to your back. If you layer gear horizontally, the back of the pack is likely to fold at the junctions between layers.

There are many ways to pack your pack! For trail hiking, carrying the weight up high lets you walk upright. Light bulky items such as sleeping bags and clothing go low in the pack; heavy items such as food go in the middle, near the back. Keep heavy items close to your back to prevent the pack from pulling backward, forcing you to lean forward. For off-trail hiking on rough ground, where balance is especially important, place heavier items in the middle rather than at the top, still as close to the back as possible, as this makes for a more stable pack.

If the pack has a frame or padded back, the first thing to go into the bottom of the pack, or the lower compartment if there is one, is my self-inflating mat, folded into a square and placed against the back of the pack so it’s well protected. In front of this goes the sleeping bag (in an oversized stuff sack inside a pack liner); when I put weight on top of the sleeping bag, it fills out the corners and helps the hipbelt wrap around the hips. Next in are my spare clothes (in another oversized stuff sack). If there’s space and the pack has a lower compartment, my rain gear goes in next to the zipper for quick access. If I’m carrying a bivouac bag, it too goes in the base of the pack. This means that the bottom of the pack is filled with soft items that are bulky for their weight.

I then slide tent poles down one side of the pack next to my back and if there is one, through the cutaway corner of the upper compartment floor. Next to go in are cooking pans, stove and fuel canisters, empty water containers, and small items such as candles and repair kit, with the heaviest items (such as full fuel containers) close to my back. Except for my lunch and the day’s trail snacks, food bags go on top of the cooking gear, close to my back because of the weight. In front of the food bags go the tent or tarp and any camp footwear. At the top of the pack I put books, spare maps, spare camera, and the windshirt or warm top I’ve been wearing to ward off the early morning chill while packing. If I can’t fit this in the top of the pack, I squeeze it into the lower compartment or into the front mesh pocket if there is one.

The lid pocket is filled, in no particular order, with hat, neck gaiter, gloves, mittens, sunscreen, camera accessories bag, insect repellent, camera lenses, dark glasses, and any small items that have escaped packing elsewhere. If there’s no lid pocket these go in a small stuff sack at the very top of the pack. One side pocket holds a water bottle, lunch, and snacks; the other holds fuel bottles if I’m using a white-gas or alcohol stove, plus tent stakes, headlamp, and first-aid kit. Any items that didn’t fit into the lid pocket or that I’ve overlooked also go in an outside pocket. Map, compass, mini binoculars, and writing materials go in a jacket or shirt pocket or hipbelt pocket. My camera, in its padded case, is slung across my body on a padded strap so it’s both well protected and accessible. Then, once I’ve shouldered the pack, tightened up the straps, and picked up my poles, I’m ready for the day’s walk.

Of course this system varies according to conditions. If I have a foam pad rather than a self-inflating mat, it goes on the outside of the pack. Rain gear can end up buried in the pack on days and in areas where it’s unlikely to be needed. Items can move from pocket to pocket at times. The aim is convenience and comfort, not tidiness and organization for their own sake.

Putting on the pack, repeated many times daily, requires a great deal of energy and more than a little finesse. With loads under 25 pounds, you can simply lift the pack and swing it onto your back. With most loads, though, the easiest way is to lift the pack using the shoulder strap (or the nylon “haul loop” attached to the top of the pack back on nearly all models), rest it on your hip, and put the arm on that side through the shoulder strap. You can then slowly swing the pack onto your back and slip your other arm through the shoulder strap.

With heavy loads (50 pounds or so), I swing the pack onto my bent leg rather than my hip, then from a stooped position I slowly shift, rather than swing, the load onto my back. Heavy loads make me aware of how much energy putting on a pack requires; whenever I stop on the trail, I try to find a rock or bank to rest the pack on so I can back out of the harness, and later back into it again. Such shelves are rare, though, so with really heavy loads (65 pounds or more) I usually sit down, put my arms through the shoulder straps, and then slowly stand up if I feel I haven’t the energy to heave the pack onto my back. I also try to take the pack on and off less often when it’s heavy; I keep items I need for the day in my pockets and rest the pack against something when I stop.

Putting on a heavy pack. (1) Grab the pack by the shoulder straps. (2) Lift it onto your bent leg. (3) Swing it slowly onto your shoulder and then … (4) … onto your back. (5) Adjust the straps for a good fit.

In camp I sometimes keep the pack in the tent—if I’m not in bear country and there’s room—but usually I leave it outside, propped against a tree or rock or lying on the ground. I leave the items I won’t need overnight in the pack, whether in or outside the tent.

During rest stops on the trail, the pack can be used as a seat if the ground is cold or wet. One advantage of an external frame is that it can be propped up with a staff and used as a backrest—its rigidity keeps it from twisting out of position and falling over, as can happen with internal-frame packs. This backrest is so comfortable that I’ve tried to make an internal-frame pack perform the same function. I’ve had some success wedging the staff into the top of the pack, but it’s much easier with two trekking poles, since then you can form a tripod. Unexpected collapses still occur, however.

Using a pack as a backrest in camp.

After a trip, I empty the pack, shake out any debris that has accumulated inside, and, if it’s wet, hang it up to dry. You can try to remove stains with soap or other cleansers; I regard such marks as adding to the pack’s character, and I’m also wary of damaging or weakening the fabric in any way, so I don’t bother.

Before a trip, I check all the zippers. I also look for signs of any stitching failure if I didn’t do so the last time I used the pack.

Most packs aren’t waterproof, whatever claims the manufacturer makes about the fabric. Water trickles in through the zippers, wicks along drawcords, seeps through the seams, and when the waterproofing has worn off, leaks right through the fabric. The few packs that are totally sealed are designed for canoeing and other watersports rather than backpacking. These have welded seams and waterproof zippers and are made from vinyl. A few—such as the 5-pound, 6,940-cubic-inch SealLine Pro Pack and the 5-pound, 6,600-cubic-inch Gaia Pack—are big enough for backpacking and might be worth considering if you expect to spend a long time in the rain.

Water-sensitive gear (down-filled items, spare clothes, maps, books) is best stored in waterproof bags. Pack covers can be used to keep rain out of the pack, but these are easily torn and can blow off. When my last one ripped I stopped using them. You have to remove them to get into the pack, too, which can let rain in. If the items inside the pack are in waterproof bags, it doesn’t matter if water enters. Some packs have built-in covers contained in the base or the lid, and a poncho can cover both you and the pack. Even if I had one of these, I’d still keep my gear in waterproof bags in wet country. The best covers are adjustable and hug the pack closely so they don’t flap in the wind. Many pack makers offer them, and they are also sold by companies like Outdoor Research, whose Hydroseal Pack Cover comes in five sizes and has daisy-chain webbing so ice axes can be attached when the cover is on.

I don’t use a single large liner that fills the pack because often there are wet items in the pack (such as the tent fly sheet and rain gear) that I want to keep separate from dry items. Instead, I put my sleeping bag and spare clothes in separate stuff sacks inside a large waterproof stuff sack and use another large sack for other items. For many years I used neoprene pack liners combined with seam-sealed Black Diamond Sealcoat stuff sacks. Both of these have long disappeared from the stores, however, and the coatings have long peeled off my most recent ones.

Dry bags with sealed seams and roll-top closures designed for watersports are a possibility but tend to be heavy and a bit stiff for stuffing in a pack. I have the XS size Ortlieb PS17 dry bag. It weighs 4 ounces, holds 793 cubic inches, and is completely watertight. The long, thin shape isn’t convenient for storing in the pack, but it does make a good cover for a foam pad in wet weather. The larger Ortlieb bags are wider and could be used as pack liners. The 4,760-cubic-inch XL Short bag weighs 12.3 ounces. Pacific Outdoor’s Pneumo Dry Bags are a bit lighter and also have a unique compression valve that allows you to squeeze out most of the air to reduce the volume. This is an exciting concept, since it could drastically reduce the packed bulk of sleeping bags and clothes. The Pneumo bags come in four sizes—305, 915, 1,525, and 3,050 cubic inches, at weights of 3, 5, 7, and 9 ounces. I haven’t tried them, but I intend to do it soon.

Nylon stuff sacks are the standard for packing gear, and many items, including sleeping bags, come with one. They’re also available separately in a wide range of shapes and sizes. However, very few are fully waterproof. They leak at the seams even if the fabric is coated. They’re fine for dry weather and when only light rain is likely. It’s in continuous rain and downpours that waterproof stuff sacks are needed, although I always carry my sleeping bag in one.