MAN IS AN ANIMAL WHO MORE THAN ANY OTHER CAN ADAPT HIMSELF TO ALL CLIMATES AND CIRCUMSTANCES.

—Walden, Henry David Thoreau

To make any walk safe and enjoyable, numerous small items (and skills) are useful. Some are essential, some are never necessary, though they may enhance your stay in the wilderness. I’m always surprised at the number of odds and ends in my pack, yet not one of them is superfluous.

No one goes backpacking in the Far North—Alaska, northern Canada, Greenland, Iceland—during midwinter because there’s little daylight—none at all if you’re north of the Arctic Circle. In midsummer, however, the Far North is light twenty-four hours a day—no artificial light is needed at “night.” Most places backpackers frequent are farther south, though, and some form of light is needed regardless of the time of year. How much you need depends on where you are and when. At Lake Louise in Banff National Park in the Canadian Rockies, there are over sixteen and a half hours of daylight in mid-June, but only eight hours in mid-December; in Yosemite you’ll have fourteen and three-quarters hours in June but more than nine and a half in December.

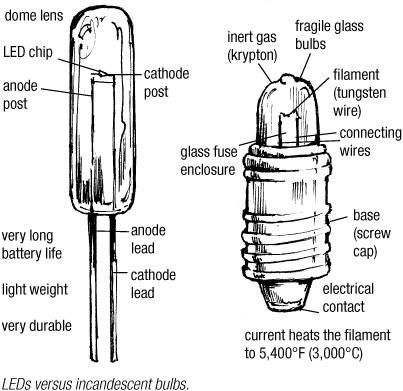

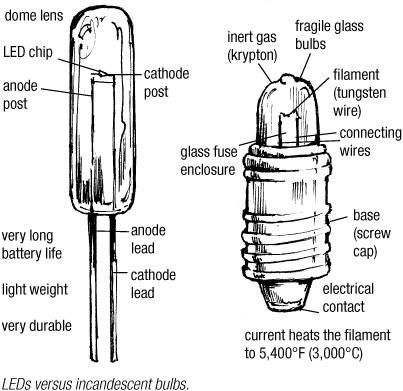

The new millennium saw a revolution in lighting with the introduction of lights using LEDs (light emitting diodes) rather than incandescent bulbs. My old headlamps are gathering dust at the back of my gear shelves, since LED lights are lower in weight, are much more durable, and use far less battery power, which means batteries last much longer, also saving weight. An LED will last for up to ten years of constant use before burning out, so most people will never need to replace one. LEDs are tough, too, unlike standard bulbs; since there’s no thin glass to shatter or thin wires to snap, they’re almost unbreakable. There really is no need to carry a spare. Battery life is greatly extended because LEDs don’t give out heat, again unlike standard bulbs, so much less energy is needed to power a headlamp—some twenty times less, in fact. The Petzl Micro with standard incandescent bulb runs for five hours on two AA alkaline batteries; the Petzl Tikka with three LEDs runs for 150 hours on three AAA alkaline batteries. The Tikka is half the weight of the Micro, too. If an LED light is turned on accidentally in your pack, the batteries are unlikely to be dead when you need it.

LED light is white rather than yellow, so colors appear as in daylight. This is particularly useful when reading maps. LED light is also unbroken, with none of those dark circles found with standard bulbs. I find it excellent for reading. LEDs aren’t perfect, however. With most the light is always a flood, which is great for illuminating a small area such as a tent and for close-up use, but it can’t be focused to a tight spot, so there’s a limit as to how far it can be projected. The number of LEDs doesn’t really affect how far the beam goes; it just determines how bright it is within the area it covers. For long distance you still need incandescent bulbs, especially halogen ones, but these bulbs use up batteries very fast and aren’t necessary much of the time. To overcome this, hybrid headlamps come with both LEDs and bulbs, so you can use the latter only when necessary. I find these headlamps useful in winter. Otherwise I prefer the lighter, smaller pure LED ones.

This problem is being overcome, however. The first 1-watt LED, said to be brighter than equivalent incandescent bulbs, is used in Princeton Tec’s Yukon HL headlamp. The lamp also has three standard LEDs for when you don’t need the bright one. The Yukon HL runs on three AA batteries and the burn times are 44 hours with the 1-watt LED and 120 hours with the three standard LEDs. It weighs 8 ounces. Black Diamond has a similar sounding headlamp, the Zenix, with a “Hyper Bright” LED with five times the light of standard LEDs and a prefocused beam. There are two standard LEDs, too. The Zenix runs on three AAA batteries, which last 12 to 15 hours with the HyperBright LED and 140 with the standard ones. I haven’t used either of these lamps but they sound like the future for backpacking lights for dark times of the year.

Wearing a headlamp leaves your hands free for tasks like making camp or cooking.

LEDs fade slowly as battery power declines, so near the end of the batteries’ life you might be able to read a book but won’t be able to see very far. Batteries that will no longer power a standard bulb will still provide light with an LED. To save batteries, you can turn down the brightness on some lights or switch off some of the LEDs.

Headlamps and handheld flashlights both have advantages and disadvantages. Overall I think headlamps are superior for backpacking. In the past, both were notorious for being unreliable. My field notes from the 1970s and 1980s reflect this: in 1985, two flashlights failed during my Continental Divide hike, and I finished that trek with a large, heavy model, the only one I could buy in a remote country store. By the end of the 1980s, however, tough, long-lasting flashlights and headlamps had swept the market. Many designs don’t have on/off switches (which failed so regularly on the older models). Instead, you twist the lamp housing to switch them on. Others have recessed switches that aren’t easily damaged or accidentally turned on.

There are a vast number of traditional incandescent bulb flashlights. A classic is the Mini Maglite AA, which runs for five hours on two alkaline AA batteries. It’s made from tough aluminum and weighs 5 ounces. It also has an adjustable beam and can be turned into a small upright lantern by using the headpiece as a stand. There’s no separate switch; you twist the head to turn it on. Smaller and lighter is the Pelican MityLite, which runs for two hours on three alkaline AAA batteries. It’s made of bright yellow polycarbonate (harder to lose than a dark-colored light), has a rotary head switch, and weighs 1.75 ounces. I’ve used the Mini Maglite and MityLite extensively, and they are both tough and surprisingly bright for such small flashlights. They tend to be used around the house rather than on the trail, however. Other reputable flashlight makers include Durabeam, PeliLite, Eveready, Streamlight, Tektite, and Princeton Tec.

Tiny LED flashlights may seem like toys rather than serious lights. They’re not, as I discovered on my first day out on the Arizona Trail when I ended up following a narrow, snow-covered trail up steep slopes in the dark. Rather than take off my pack and dig out my headlamp, I used a single LED Sapphire Light weighing half an ounce that I happened to have in a pants pocket. You have to keep the switch pressed to get a light, so I just used it every few yards or so to check where the trail went next. It was just adequate. It’s guaranteed for life, including the batteries, but it’s since disappeared—the only problem with such small lights. I replaced it with an even smaller Princeton Tec Pulsar (it’s a touch bigger than a quarter) that weighs a quarter of an ounce and mostly lives on my key ring. The two lithium cells are meant to last twelve to fourteen hours, which is a lot of squeeze time. I wouldn’t rely on one of these tiny lights alone, except maybe in the Arctic in summer, but one makes a good backup. Larger LED flashlights are made by various companies such as Streamlight and Lightwave.

Handheld lights are less costly than headlamps, and there’s a much wider choice, but they’re far less versatile, especially for camping. Many years ago I discovered that a headlamp is much more useful because it leaves both hands free. After having pitched tents and cooked while gagging on a flashlight held in my mouth, stopping every few minutes to recover, using a headlamp was a revelation. First developed for predawn starts on Alpine mountaineering routes, many of the best headlamps come from mountaineering equipment manufacturers such as Petzl and Black Diamond. In early models, wires trailed from the lamp to battery packs you clipped to your belt or carried in a pocket, and they constantly caught on things. Then came headlamps with the battery case on the headband, a design far more compact, lightweight, and easy to use.

There are various webbing headbands that can adapt a small flashlight for use as a headlamp. I have a Nite Ize headband (1 ounce) that takes a Mini Maglite. It’s not as comfortable as a real headlamp, and you can’t adjust the direction of the beam, but it does leave your hands free.

For many years I used French-made Petzl headlamps exclusively, since they had the best designs along with superb quality. They always proved very comfortable and reliable. In winter I used the classic Petzl Zoom, a powerful light weighing 11.5 ounces with a flat 4.5-volt battery; in summer I used the lighter Micro, weighing 5 ounces with two AA batteries. These have now been replaced by LED headlamps, both in Petzl’s range and in my gear store.

Petzl took the lead with the new LED lights; their tiny three-LED Tikka and Zipka were the first LED headlamps. They’re ultralight, too, at 2.5 ounces for the Tikka, which has a wide elasticized headband, and 2.25 ounces for the Zipka, which has a retractable cord. When the Tikka first appeared it immediately became my most-used headlamp, and I’ve used one for many months in total. It’s very comfortable to wear since it’s so light, but it doesn’t have a swivel head, which can be awkward at times. The switch is recessed and quite stiff; I’ve never had it turn on by accident. Petzl has followed up these headlamps with the 2.75-ounce Tikka Plus and 2.3-ounce Zipka Plus, each with a tilting head, four LEDs, and four power settings.

The Tikka was soon followed by a growing mass of LED headlamps, several of which I’ve tried. The lightest by far is the Black Diamond Ion, a tiny but powerful two-LED light that weighs a fraction over an ounce with battery. It has a comfortable headband and a swivel head. I used one as my only light on a five-week hike in the High Sierra one summer and found it adequate even for hiking and making camp after dark. The relatively short fifteen-hour battery life is a downside, though. The 6-volt batteries are quite expensive and hard to find, too. Slightly heavier is the two-LED Princeton Tec Scout at 2 ounces with batteries. This runs off four 2032 lithium coin cells. It has three power levels—high, medium, and low—and two flash modes. Battery life is twenty-four, thirty-six, and forty-eight hours for the different modes.

The three-LED Princeton Tec Aurora has become my favorite headlamp for summer use. It weighs half an ounce more than the Tikka but has a swivel head and three brightness settings. The only niggle is that the switch is easily depressed, so you have to take care not to switch it on unintentionally. Slightly heavier at 4 ounces but also a bit brighter with four LEDs is the Black Diamond Moonlight. This also has a battery box on the back of the headband rather than immediately behind the LEDs, plus a third strap that runs over the top of the head. This makes it more comfortable to wear for long periods than the smaller headlamps, and it can’t slip down. There’s no cover over the LEDs; Black Diamond says this isn’t necessary. The push-button switch can be protected from accidental pressure when the headlamp isn’t in use.

From late fall to early spring, when hiking and camping in the dark is more likely owing to longer nights and a brighter, more focused light can be useful for selecting campsites and illuminating the route some distance ahead, I carry a hybrid headlamp with LEDs and an incandescent bulb. All these heavier headlamps have straps that run over the top of the head as well as a headband and battery boxes that sit on the back of the head. Of the models I’ve tried, my favorite is the Petzl Myo, which replaces the Zoom. This comes in three versions. The standard Myo just has a xenon halogen bulb. The Myo 3 has three LEDs as well, the Myo 5, five LEDs. I have the 8.5-ounce Myo 3, and it’s an excellent headlamp. It has a swivel head that you twist to turn it on and a zoom function with the halogen bulb so you can spread the light or focus on a specific point. The head can be locked in place so it doesn’t turn on accidentally.

The Petzl Myo 3 with three LEDs and halogen bulb (left) is good for when you need a long beam. The Black Diamond Moonlight with four LEDs (middle) and the Princeton Tec Aurora with three LEDs (right) are good for most uses and are very economical with batteries.

Other good LED/bulb headlamps are the 9-ounce Black Diamond Supernova, which has just one LED plus a useful 6-volt backup battery that powers the LED if the main batteries run out. There are three brightness settings with the halogen bulb. It’s a good headlamp but would be better with more LEDs. Petzl’s Duo comes with three, five, or eight LEDs plus a halogen bulb. I tried the Duo LED 5 and it’s fine, though bulkier and heavier than the Myo. The head pivots, with a noisy cracking, and the beam zooms in and out with the halogen bulb. The click switch can be locked in place. Princeton Tec’s Switchback has three LEDs and a zoom beam. The main point of interest is the separate battery pack that takes four C cells that will run the standard bulb for twenty-four hours and can be stored in a pocket in freezing weather. The push-button switch is stiff and has to be held down for a while before the light comes on, so it’s unlikely to be operated by accident. Other good-looking headlamps come from Tektite and Pelican.

Whatever light you use, it needs to be handy when you need it. I usually carry mine in a pack pocket. In camp I keep it close to the head of my sleeping bag so I can find it without too much trouble if I wake up in the dark.

With an LED light I don’t bother carrying spare batteries unless I’m out for several weeks (or can’t remember how much use the batteries in the headlamp have had). If you don’t have an LED light, it’s wise to carry spare batteries and bulbs. Standard tungsten bulbs are fine for camp use and don’t use up batteries quickly. With lights that use only a few AA or AAA batteries, the beam is quite weak, however, and not good for walking in the dark. Krypton light is yellow, too, which can make reading maps difficult. Halogen and xenon bulbs (the space-age names refer to the gas they’re filled with) are much brighter and throw a whiter light, but they also use up batteries much more quickly. Alkaline batteries are standard. Alternatives are lithium and rechargeable batteries (nickel-cadmium, or nicads, and nickel–metal hydride, or NiMH). Lithium batteries are expensive, but they last much longer than alkaline ones in cold weather; they also maintain a steadier beam until their power is completely drained. Lithiums are slightly lighter as well. Two Energizer 2 lithium AA batteries weigh 1.5 ounces, and two alkaline batteries weigh 2 ounces. Lithium batteries are also available in AAA, but not C or D sizes. In temperatures above freezing, lithium batteries have no advantages over alkalines when used in low-drain items like flashlights or headlamps. I use lithiums on trips where I expect bitter cold, but not on summer hikes.

Rechargeable batteries make environmental sense, since disposable batteries are toxic and require much energy to produce. Early rechargeables were difficult to use; they took a very long time to recharge and needed to be fully drained before being recharged again. The latest ones are much easier to use; they can be recharged in a few hours, and they don’t need to be fully drained before recharging. Indeed, NiMH batteries should be recharged before they are fully drained. NiMH batteries are more environmentally friendly than nicads, since they contain no toxic materials, whereas nicads contain the rather nasty heavy metal cadmium, and they’re easier to use. They can be recharged hundreds of times—up to a thousand, says Energizer of its NiMH battery. They don’t hold a charge very long in warm temperatures, however. If you keep them in a freezer the charge lasts a long time, but that isn’t much use on long hikes in anything but winter conditions.

A solar charger seems to be the answer, and there are several portable ones. I have a Brunton Battery Saver AA solar charger that charges four AA cells. It weighs 8 ounces, however, and so far I’ve used it only on a south-facing windowsill. It takes about twelve to sixteen hours of bright sunshine to charge four batteries, which on my windowsill means at least four sunny days. I live at 58 degrees north, though. Those living farther south should be able to charge batteries much more quickly.

Solar World’s SPC-4 at 1.5 ounces looks to be the lightest charger for trail use. It charges four AA or AAA batteries. To use a solar charger effectively you’d have to strap it to the top of your pack or else spend several hours in a very sunny spot. Of course, if you stay in one place for a day you could use it then. I intend taking a solar charger on a hike to see how well it works, but I’ll carry some alkaline cells as backup. I suspect that charging batteries at home will be easier.

Candles give out a soft, pleasant light plus a little heat. I often use one in camp for reading and making notes. On cold, dark winter nights, I’m always amazed at how much warmth and friendliness a single candle flame can give, especially if you put the stove windscreen behind it as a reflector and to keep off breezes. The candles designed for candle lanterns (see below) have fairly wide bases and stand up on their own. Ordinary household candles are less expensive but need to be propped up with a tent stake or small stones or dug into the ground to stop them from falling over. I put a candle on a rock or an upturned cooking pot in a place where it won’t land on anything flammable if it falls or is knocked over. I use candles in tent vestibules but never bring one into the inner tent. Used this way a lit candle is fairly safe, as long as you don’t leave it unattended. After melting holes in two doors, I also make sure the candle isn’t too close to the fly sheet. Because batteries last so long in LED lights, I don’t often carry candles in the summer anymore. In winter the warmth is welcome.

Candle lanterns protect the flame from wind and can be hung up so the light covers a wider area. One will easily light a small tent or the area around the head of your sleeping bag if you’re sleeping under the stars. Most come with hanging chains, but these are rather short; I add a length of cord so I can hang the lantern from a branch. The heat from the lantern isn’t enough to melt the cord—or at least it hasn’t done it yet. The lanterns themselves do get hot, though, and need to be kept away from anything that might melt. If you stand the lantern on the ground there should be enough space for it to topple over without setting anything on fire.

When they work properly candle lanterns are excellent, but problems do arise. The most common design uses a glass cylinder to protect the flame and a metal or plastic candleholder. The glass slides into the candleholder to protect it when packed. The candleholder has a spring in its base that pushes the candle up as it burns. UCO and Northern Lights are the main brand names. Candle lanterns weigh 5 to 8 ounces, depending on the model and the material (some are aluminum, some brass, some thermoplastic). A candle—they take stubby ones rather than household candles—adds 2.5 ounces. Candles can last eight to nine hours, but in practice I’ve found that most start to sputter and overflow before they’re two-thirds used, leaving the inside of the lantern covered with wax that has to be scraped off—not an easy job, especially in camp in the dark. Part of the reason seems to be that most wicks don’t run straight down the middle of the candles but curve off to the side halfway down. Although I used to use one regularly, it’s now many years since I used a candle lantern, mainly because of this problem with the candles. In summer an LED light is adequate, and in winter I carry a plain candle if I want to keep the weight down or a butane-propane lantern if weight isn’t so significant. There are lightweight lanterns that burn the little “tealight” tub candles. UCO makes one called the Mini, and Olicamp makes one called the Footprint Lantern. Both weigh 3 ounces. I find tub candles too dim to be useful, however.

A candle lantern provides light and warmth.

For a while I used my lantern with a thermoplastic insert called a Candoil that burns lamp oil via a cotton wick. It can also burn kerosene, though it’s very smoky. The Northern Lights Candoil insert weighs 3.5 ounces. It’s not as bright as a candle, and the wick has to be adjusted to just the right length to minimize smoking and maximize light output, which is a little fiddly and can take time. The Candoil holds about 1.7 fluid ounces of lamp oil and burns ten to twelve hours. Northern Lights also makes the Ultra Light, an oil-burning lantern that weighs 5.5 ounces and burns for seventeen hours on one fill. Even with lamp oil, I always ended up with greasy fingers after using the Candoil, the main reason I stopped using it.

An interesting new twist is the UCO Duo, which has an LED light in the base so you can use the lantern as a flashlight. You can also remove the LED and attach it to a headband. The batteries are said to last forty hours. The base doesn’t add any extra weight, since it replaces the normal one. The LED base can be bought separately if you want to fit one to your lantern.

Lanterns that run off butane-propane cartridges are fine for base camps and for backpacking in winter when a bright light and a little warmth can be welcome. They emit a constant hiss when lit, which can be irritating, though I soon got used to it. They use far less gas than stoves, since the heat output is much less, and will run well on almost empty cartridges that will barely power a stove.

Most lanterns have glass globes that surround and disperse the light from a glowing, lacelike mantle, which in turn surrounds a jet. Both the globe and the mantle are fragile, and the lantern must be protected in the pack.

Many lanterns are quite heavy, but a few are light enough for backpacking. I’ve had a Coleman Peak 1 Micro Lantern for many years and have used it often on winter trips. It weighs 7 ounces and has protective lightweight steel bars around the globe. The output is a bright 75 to 80 watts. It runs off standard resealable cartridges. More recently I’ve tried Primus’s similar EasyLight lantern, which weighs 7.5 ounces and also runs off standard cartridges. The EasyLight has electronic Piezo ignition, which does make lighting it much easier, since you don’t have to remove the top and risk burning your fingers when you insert a match. Although I don’t like Piezo ignitions with stoves, in lanterns they seem much more durable, since they’re protected inside the globe. The 7-ounce Campingaz Lumostar C270 lantern runs off CV cartridges, which could be useful in places where these are sold rather than standard ones. Coleman makes a lantern—the 12-ounce Exponent—that runs off Powermax fuel (see pages 299–300). It doesn’t use the cartridges, though. Instead it has a fuel tank that is filled from a Powermax cartridge. Brunton also make a refillable lantern, the strangely named Glorb, that weighs 8 ounces and runs off butane lighter fluid. The Glorb has Piezo ignition, and the light output can be varied for a dimmer or brighter light. The maximum output is 60 watts.

The best-looking lantern for backpacking however is the Primus Micron. This lantern weighs just 4.4 ounces and has stainless steel mesh instead of a breakable glass globe. The Micron lantern uses the same system as the Micron stove, including the Piezo lighter, and is meant to be very fuel efficient. It’s also said to be quieter than other cartridge lanterns. Output is 70 watts. I’m looking forward to trying one.

White-gas and kerosene lanterns are heavier; at 30 ounces, the Coleman Peak 1 Liquid Fuel Lantern is one of the lightest. I wouldn’t bother with one for backpacking.

Lightsticks are thin plastic tubes that when bent break an internal glass capsule, allowing two nontoxic chemicals to mix and produce a pale greenish light. To me they seem no more than a curiosity (at least for backpacking). I’ve never carried one. If you want an emergency light a tiny LED one would be the best choice.

Basic first-aid knowledge is essential for hikers, since it may be some time before help arrives if there’s an accident. Taking a Red Cross, YMCA, or similar first-aid course is a good idea. Many outdoor schools also offer courses in wilderness first aid. There are many books on the subject, too. Medicine for Mountaineering, edited by James Wilkerson, is the standard work. It’s comprehensive and good for home reference, but at 26.5 ounces it’s rather heavy for carrying in the pack. More portable at 6.5 and 7 ounces are Paul Gill’s Wilderness First Aid and William Forgey’s Basic Essentials: Wilderness First Aid. Even lighter at 4 ounces and the only first-aid book I’ve ever actually carried is Fred Darvill’s clear and concise Mountaineering Medicine. Be forewarned: a close study of these texts may convince you that you’re lucky to have survived the dangers of wilderness travel and that you’d better not go back again! (The antidote to this is a glance through the statistics on accidents that occur in the home and on the road—driving to the wilderness is likely to be far more hazardous than anything you do in it.)

First-aid basics consist of knowledge, skill, and a few medical supplies. The last are only of use if you have the first two. There are many packaged firstaid kits. Some are very good, some are pretty poor. Outdoor Research, Adventure Medical, and REI are among those that offer good ones. But the problem with even the best ones is that they usually contain items I don’t feel are necessary, while items I consider essential are absent. Putting together a kit from the shelves of the local drugstore, as I do, means you get exactly what you want. It also means you know what you’ve got and are likely to know how to use it. I’ve been surprised at how many people with packaged kits don’t know what’s in them, let alone how to use everything.

Every book on wilderness medicine and backpacking features a different list of what a first-aid kit should contain. Many years ago I carried a fairly comprehensive kit (weighing a pound), but in keeping with cutting weight wherever possible, I now take it only when I’m venturing into remote areas where help could be many days away. The total weight has dwindled to 8 to 10 ounces, too.

Mostly I carry a small kit weighing 4 to 5 ounces. The contents vary, but it usually contains:

first-aid information leaflet

first-aid information leaflet

1 6-inch-wide elastic or crepe bandage for knee and ankle sprains

1 6-inch-wide elastic or crepe bandage for knee and ankle sprains

4 2nd Skin Blister Pads or other gel dressings

4 2nd Skin Blister Pads or other gel dressings

roll of 1-inch tape for holding dressings in place

roll of 1-inch tape for holding dressings in place

2 2-by-2-inch nonadhesive absorbent dressings for burns

2 2-by-2-inch nonadhesive absorbent dressings for burns

2 butterfly closures

2 butterfly closures

3 or 4 antiseptic wipes for cleaning wounds and blisters

3 or 4 antiseptic wipes for cleaning wounds and blisters

12 assorted adhesive bandages for cuts

12 assorted adhesive bandages for cuts

10 foil-wrapped painkillers—ibuprofen or aspirin

10 foil-wrapped painkillers—ibuprofen or aspirin

2 safety pins for fastening slings and bandages

2 safety pins for fastening slings and bandages

I keep the kit in a small zippered nylon case marked with a large white cross and the words First Aid. Having your first-aid kit clearly identifiable is important in case someone else has to rummage through your pack for it. There are no scissors or tweezers in the kit because I have these on my knife and no large bandages because a bandanna or torn piece of clothing could be used. Other items can be used for first aid too—needles and thread, duct tape, moist wipes, even pack frames, foam pads, or tent poles for splints.

For a larger kit I usually add the following:

1 4-by-6-inch sterile dressing for major bleeding

1 4-by-6-inch sterile dressing for major bleeding

2 sterile lint dressings for severe bleeding

2 sterile lint dressings for severe bleeding

1 7-inch elastic net to hold a dressing on a head wound

1 7-inch elastic net to hold a dressing on a head wound

extra antiseptic wipes

extra antiseptic wipes

4 butterfly closures

4 butterfly closures

4 2nd Skin Blister Pads or other gel dressings

4 2nd Skin Blister Pads or other gel dressings

triangular bandage for arm fracture or shoulder dislocation

triangular bandage for arm fracture or shoulder dislocation

4 safety pins

4 safety pins

1 4-by-4-inch sterile nonadhesive dressing for burns

1 4-by-4-inch sterile nonadhesive dressing for burns

20 extra painkillers

20 extra painkillers

On long walks in remote country I also carry prescription antibiotics in case of illness or infection and prescription painkillers—ask your doctor about this. If you need personal medication, it will have to be added to the kit as well, of course. Such medicines don’t last forever, though—be aware of expiration dates.

Groups need to carry larger, more comprehensive kits. The one I take when I’m leading ski tours weighs 24 ounces. A plastic food storage container keeps a large first-aid kit from being crushed. Nylon pouches are lighter, however, and fine for the smaller kits.

It’s wise to have a dental checkup immediately before a long trip. I can tell you from painful experience that a lost filling or an abscess is to be avoided if at all possible. If your teeth, like mine, are as much metal as enamel, I suggest carrying temporary filling materials such as Dentemp or Cavit. If you’re really concerned about tooth problems, you could take an emergency repair kit such as the Adventure Medical Dental Medic kit. This comes in a waterproof case and contains a tube of temporary cavity filling material, a wax stick for filling cavities or stabilizing loose teeth, anesthetic gel for pain, a black tea bag for relief of dental pain and bleeding, 12 yards of dental floss, 3 toothpicks, 5 gauze pellets, 5 gauze rolls, and an instruction sheet for various dental emergencies.

It’s surprising how long you can go without washing your hair or body; I managed twenty-three days in the High Sierra on the Pacific Crest Trail. When every drop of water you use has to be produced laboriously by melting snow, washing—except for your hands—becomes unimportant, though I did occasionally rub my face and armpits with snow. Still, a minimum of cleanliness is necessary. In particular, you should always wash your hands after going to the toilet and before handling food. I usually manage to rinse my face most days as well. When it’s cold, I save more thorough washing for when I get home or, on long trips, for a shower in a motel or campground. In hot weather I wash more often, if only to stay cool. Large water containers hung from trees make good showers—if you leave them in the sun for a few hours beforehand, the water is surprisingly warm.

Proper hand washing is essential in a group to avoid spreading stomach bugs, and it’s wise for solo hikers as well. There are several phosphate free, biodegradable soaps, including Coghlan’s Plus 50 Sportsman’s Soap in small squeeze tubes weighing an ounce, Campsuds in 2- and 4-ounce plastic bottles, Mountain Suds Backpacking Soap in 2-ounce bottles, and Dr Bronner’s Soap (various scents) in 4-ounce plastic bottles. Even these soaps can pollute water sources, however, so use a minimum amount and dispose of washing water on gravel or rock at least 200 feet from any lake or stream. I prefer moist wipes, which I drop in my garbage bag after use, or hand-sanitizer gel; neither requires any water. On long trips I’ve carried a pack of fifty wipes. Mostly, though, I decant two or three a day into a Ziploc bag. Most recently I’ve been carrying antibacterial Atwater Carey Hand Sanitizer, which comes in 2-ounce plastic bottles, since this leaves no residue or trash to carry out. The main ingredient is ethyl alcohol, so once you’ve rubbed some on your hands it evaporates very quickly, leaving your hands feeling fresh. Whether I carry sanitizer or wipes, they go in the plastic bag with my toilet paper to remind me to use them immediately after defecating.

If you want to do more than wash your hands or face, No-Rinse Bathing Wipes are larger than standard ones. They can be useful for removing dirt and sweat at the end of a trip so you don’t smell too bad on the journey home or in that first restaurant. No-Rinse also makes 2- and 8-ounce bottles of No-Rinse Shampoo and Body Wash that could be used for the same purpose.

I don’t carry a cotton washcloth or towel; both are heavy and slow to dry. A bandanna does for the former, a piece of clothing for the latter. Fleece jackets make particularly good towels. If you don’t fancy using clothing to dry yourself, there are small, light pack towels. Cascade Designs’ Packtowl is made from a highly absorbent viscose material and comes in several sizes. The smallest 10-by-30-inch size weighs 1.5 ounces, the extra-large 30-by-50-inch weighs 7.5 ounces. The Packtowl works surprisingly well. I’ve tried the small one, which is fine for hands and face, and it soaks up masses of water—nine times its own weight, according to Cascade Designs—most of which can be wrung out so you don’t have to carry it. Tie it on the back of the pack, and the Packtowl dries quickly.

My current wash kit consists of a small toothbrush (without the handle removed), a very small tube of toothpaste (I collect those often provided on long-distance flights, or you can decant some into a tiny plastic bottle), moist wipes, and a comb. The kit weighs about 2 ounces in its Ziploc bag. Like soap, toothpaste should be deposited a long way from water. You can get biodegradable toothpaste, but toothpaste isn’t essential anyway; if I run out I do without. I carry a comb so I can look somewhat presentable in towns on long hikes. If I won’t be passing through any towns I leave the comb in my car or with any clean clothes I’ve left to be picked up after the hike.

I don’t shave, so I don’t carry a razor. Those who do shave carry disposable razors—and usually curse them and the difficulty of shaving in the wilds—or else a tiny battery-powered shaver, such as Braun’s Pocket Twist, which runs on two AA batteries.

If you’re unprepared, swarms of biting insects—mosquitoes, black flies, no-see-ums—can drive you crazy in certain areas during the summer. Bites can itch maddeningly for hours, even days. I’ve yet to meet anyone immune to insect bites, though sensitivity varies and some people suffer much more than others. Biting insects are usually found in damp, shady areas. Camping in dry, breezy places is one way to minimize insect problems, though it’s often not possible. Insects are usually less evident when you’re walking, but the moment you stop anywhere sheltered they’re likely to appear. The increase in West Nile virus, spread by mosquitoes, makes prevention important. West Nile virus affects the central nervous system and can be serious.

Insect repellent and clothing are your main defenses. You can cover up with tightly woven, light-colored clothing (dark colors apparently attract some insects) and fasten wrist and ankle cuffs tightly. A head net (1 to 2 ounces), worn over a hat with a brim or bill to keep it off your face, is extremely useful. It’s the only defense I’ve found against black flies, which seem immune to repellents. If you’re likely to need a head net often, Plow and Hearth’s 4-ounce cotton Bug Cap comes with a nylon head net that rolls into a pouch on the bill. Any head net needs some form of closure at the bottom or else loops that fit under your arms to prevent it from riding up. Clothing made from no-see-um netting is available, but I’ve never used any. Netting clothing needs to be held away from the skin, since insects can bite through it.

Any uncovered skin needs to be protected with repellent if you don’t want to be bitten. The most effective is reckoned to be DEET, short for N, N-diethyl-meta-toluamide or N, N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide, the active ingredient in most insect repellents. Well-known brands include Muskol, Cutter, Ben’s 100, Jungle Juice, Repel, Sawyer, Buggspray, and Deep Woods Off! Small bottles and tubes weigh about an ounce. Creams are the easiest to apply, but liquids go further. DEET repels most biting insects, including ticks. It also melts plastic, so it needs to be kept away from items such as watches, pocketknives, GPS units, and cameras.

DEET was developed by the U.S. Army in 1946 and first registered for public use in 1957, so it’s been around a long time. It’s considered safe by the EPA, which reregistered it in 1998, as long as instructions are followed. These include not applying it over cuts, wounds, or irritated skin, using just enough to cover skin or clothing and not using it under clothing. Wash skin once the repellent isn’t required anymore, and wash treated clothing before using it again. The latest DEET repellents feature controlled release and contain about 20 percent DEET. Because the DEET is released slowly, one application can last all day. Sawyer says its Controlled Release Lotion works for twenty hours.

Some people react badly to DEET and feel unwell or nauseated if they use it or even smell it. My partner Denise reacts like this and never uses the stuff. Although I don’t use DEET anymore, I did for many years without any adverse reactions—except that Denise wouldn’t come near me! However, I was never too happy with the idea of putting something on my skin that could dissolve plastic and make some people feel ill, and since an increasing amount of gear had to be kept away from it, it seemed easier to use an alternative. If you do use DEET, you can keep it off your skin by applying it to clothing.

Oil of citronella (Natrapel is the main brand) is the traditional alternative to DEET. A more recent one is lemon eucalyptus, found in Avon Skin-So-Soft Bug Guard, Repel Lemon Eucalyptus, Badger Anti Bug Balm, and Off! Botanicals Insect Repellent. Most of these come in 4-ounce pump bottles and 2-ounce tubes. My experience is that citronella doesn’t work very well and eucalyptus is better. The active ingredient in eucalyptus repellents is citriodiol, which is said to last for six hours before it needs to be reapplied.

Other suggested ways of repelling insects include massive doses of vitamin B or eating lots of garlic. I can’t vouch for these.

Repellents do just that. They repel, not kill. Pyrethoids are insecticides and kill insects on contact. The original pyrethrum comes from chrysanthemum flowers, though many pyrethoids are now synthetic. Permethrin is a common one. Pyrethoids can be used for backpacking in two ways: as sprays for tents and clothing and as coils for burning in camp. Sawyer 6-ounce EcoPump Spray and Repel Permanone Trigger Spray are two types of pyrethoid sprays. I’ve sprayed tents with permethrin and found that it stops insects from landing on the tent so you don’t wake up with the fly sheet black with them. You should use these sprays at home and let the tent dry before use. Applications are said to last up to two weeks of exposure to light. When sprayed items are stored in the dark the permethrin doesn’t degrade, so items don’t need retreating before use if they’ve had less than two weeks’ use. There’s no point in putting permethrin on your skin, since it will last only fifteen minutes. It can be used on clothing though, including head nets.

In an enclosed space such as a tent vestibule or under a tarp, burning a mosquito coil can keep insects away. On my walk through the Yukon, I often lit a coil at rest stops and found that even in the open it kept mosquitoes away. You can also buy citronella candles, but these are much heavier than coils. Coils come in packs of ten or twelve weighing about 7 ounces. Each coil lasts five to ten hours. When lit, they smolder like an incense stick, sending wreaths of insect-repelling smoke into the air. Remember that the end of a burning coil is hot and can burn you and melt holes in synthetic gear.

Making camp when bugs are biting requires speed and a fair bit of teeth gritting. I pitch the tent as fast as possible, fill my water containers, get in the tent, close the fly sheet door, light a mosquito coil in the vestibule, and stay there until dawn. No-see-ums will enter by the thousands under a fly sheet if no coil is burning, so I set up a coil last thing at night, then sleep with the insect-netting inner door shut. By dawn the inner door is often black with hungry no-see-ums and the vestibule is swarming with them. I unzip a corner of the netting, stick my hand out, strike a match, and light the coil. Then I retreat and close the netting again. Within five minutes most of the insects will be gone or dead, and I can open the inner door and have breakfast in peace. I keep the coil burning until I leave the tent. The tent often becomes hot and stuffy and stinks of burnt coil, but it’s better than being bitten or having to eat breakfast while running around in circles, as I’ve seen others do. Even if you douse yourself with repellent, no-see-ums will make your skin and scalp itch maddeningly by crawling in your hair and over any exposed flesh, even though they won’t bite. You shouldn’t use repellent in bear country, of course, so a breezy kitchen site is a good idea. Otherwise you just have to be as quick as possible, perhaps making do with cold food and drink.

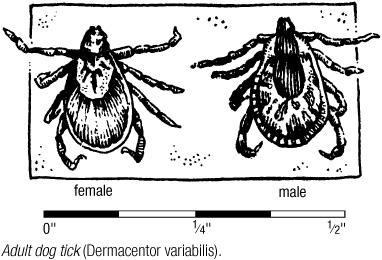

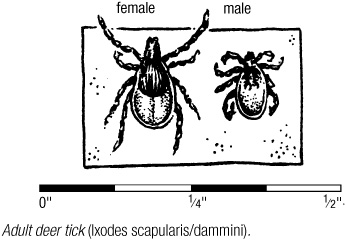

Ticks, which are arachnids, not insects, are usually no more than an unpleasant irritant, but they can transmit Rocky Mountain spotted fever (found mainly in the East, despite the name) and Lyme disease. Luckily, both can be cured with timely treatment. Symptoms of Rocky Mountain spotted fever, which include the sudden onset of fever, chills, severe headache and muscle ache, general fatigue, and a loss of appetite, begin to appear two to fourteen days after a bite. A rash will develop within two to five days, beginning first on wrists, hands, ankles, and feet. If untreated, the disease lasts for a couple of weeks and is fatal in 20 to 30 percent of cases, depending on one’s age.

Lyme disease also appears a few days to a few weeks after a bite and usually involves a circular red rash, though not always. It isn’t fatal, but if not treated it can recur years later and lead to bizarre symptoms and severe, crippling arthritis.

A more common, though less serious, tickborne illness is Colorado tick fever, which appears four to six days after the tick bite. Symptoms are fever, headache, chills, and aching. Your eyes may feel extra sensitive to light. The illness lasts, on and off, for about a week. There is no specific cure, but most victims recover completely.

If you are bitten by a tick and feel ill in the next three or four weeks, consult a doctor.

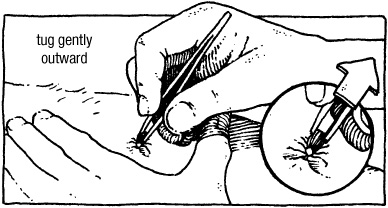

A sensible precaution is to check for ticks when you’re in areas where they occur (local knowledge is useful here) and when you’re walking in tick season, usually late spring and early summer. Ticks crawling on your body can be detached with tweezers (found on most Swiss Army Knives)—apply these to the skin around the tick not the tick itself so the head isn’t left in the flesh. Pull ticks straight out, along with a tiny bit of skin. Don’t twist or burn embedded ticks, because the mouthparts could remain in the wound and cause infection. Body searches usually locate most unattached ticks, though some ticks are no bigger than a pinhead. (Searches work better when two people “groom” each other.) Tick kits weighing a couple of ounces consist of a magnifier, curved tweezers, antiseptic swabs, and instructions. The Tick Nipper Tick Remover looks like a pair of plastic pliers and includes a 20x magnifier, while the Pro-Tick Remedy is made from steel. Both items weigh 0.5 ounce.

Ticks live in long grass and vegetation and attach themselves to you as you brush past. A tick then crawls about for a while, possibly for several hours, before biting and starting to suck blood. The bite is painless and doesn’t itch, which is why body searches are necessary. Long pants tucked into your socks or worn with gaiters protect against ticks. If your clothing is light colored it’s easier to spot the dark ticks crawling around on it.

To remove a tick, grasp it at the mouth end with fine tweezers or a tick removal tool. Tug gently outward until the tick lets go. A tick removal kit containing magnifier, curved tweezers, antiseptic swabs, and instructions can be handy.

Bee and wasp stings can be very painful. There are various remedies. Sting Eze is a liquid antihistamine in a 2-ounce bottle; antihistamines also come in tablet form. (Use antihistamines, however, only when there are signs of an allergic reaction, such as hives, wheezing, or facial swelling.) People who have adverse reactions to stings should carry an EpiPen containing epinephrine (a prescription medication) and inject this as soon as symptoms appear. Bees leave their stingers behind in the wound. A Sawyer Extractor suction pump (3.5 ounces) can be used to suck the stinger out of the skin, or you can scrape it out with a knife blade. A moist aspirin taped over the sting site is said to stop pain.

Protecting your skin against sunburn is a necessity—sunburned shoulders are agony under a pack, and a peeling nose also can be very painful. In the long run, overexposure may increase the risk of skin cancer. To minimize burning, use sunscreen on exposed skin whenever you’re in sunlight, especially between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. when the sun is strongest. Don’t forget your feet if you’re wearing sandals without socks. Brimmed and peaked hats help shade your face and cut the need for sunscreen, as does long, tightly woven clothing.

All sunscreens have a sun protection factor (SPF); the higher the SPF, the more protection. SPFs of 15 and above are recommended, especially for high altitudes, where ultraviolet light (the part of the spectrum that burns) is stronger. UV light increases in intensity 4 percent for every 1,000 feet of altitude. I burn easily, so I apply a sunscreen of SPF 15 or higher several times a day. Snow reflects sunlight, so when crossing snow-fields protect all exposed skin, including that under your chin and around your nostrils. The best sunscreens are creamy rather than greasy and don’t wash off when you sweat—at least not quickly. They should protect against both UVA and UVB rays; both can damage the skin, though it’s the latter that cause sunburn. The skin is damaged long before it starts burning. Surveys suggest that most people don’t use enough sunscreen (independent surveys, not those sponsored by sunscreen makers). Apply it lavishly and often, starting a half-hour before you venture into the sun. Large bottles are the least expensive. Small amounts can be decanted into smaller containers with secure lids for carrying in the pack. Sunscreen has a shelf life of three to four years, so you don’t need to use it up quickly.

If you get sunburned, various creams and lotions will help reduce the suffering, but it’s best to avoid the problem in the first place. I don’t carry any sunburn treatment.

Lips can suffer from the drying effects of the wind as well as from sunburn, and they can crack badly in very cold conditions. A tube of lip balm weighs less than an ounce yet can save days of pain.

Most of the time I don’t wear sunglasses, except during snow travel, when they are essential to prevent corneal burning, a very painful condition known as snow blindness. This can occur even when the sun isn’t bright, as I learned on a day of thin mist in the Norwegian mountains. Because visibility was so poor and wearing sunglasses made it worse, I didn’t wear them but skied all day straining to see ahead. Although I didn’t suffer complete snow blindness, my eyes became sore and itchy; by evening I was seeing double, and my eyes were painful except when closed. Luckily it was the last day of my trip; otherwise I would have had to rest for at least a couple of days to let my eyes recover. It’s my guess that sunlight filtered through the fine mist and reflected off the snow. I should have worn sunglasses with amber or yellow lenses, since these improve definition in poor light, and I now always carry a pair.

The main requirement of sunglasses is that they cut out all ultraviolet light, which cheap ones may not do. Those designed for snow and high-altitude use should also cut out infrared light. Glass lenses are scratch resistant; polycarbonate lenses weigh less. Large lenses that curve around the eyes are best, since they give the most protection. Quality glasses include Bollé, Vuarnet, Ray-Ban, Cébé, Julbo, Smith, Native Eyewear, and Oakley. For snow use, glacier-type glasses with side shields are best. They are essential at high altitudes. I have two pairs of glacier glasses, Julbo Sherpas (1 ounce) with gray lenses for bright light, and Bollé Crevasses (1.5 ounces) with amber lenses for hazy conditions. I always carry both pairs on trips in snow, both to deal with different conditions and because losing or breaking a pair could be serious. On summer hikes where I might encounter snow, pale sand, or rock, I carry the Sherpas with the side shields removed. I rarely wear them, however; I prefer a hat to shade my eyes.

If fogging is a problem there are antifogging products such as the Smith No Fog Cloth. I’ve never used these, but people who wear glasses all the time tell me they’re quite effective.

Keeping glasses on can be a problem, especially when skiing. The answer is a loop that goes around your head or neck. Glacier glasses usually come with these, but many sunglasses don’t. Various straps, such Croakies and Chums, slip over the earpieces. I’ve used Croakies, and they work well.

In severe blizzards and driving snow, goggles give more protection than glasses. For well over a decade I’ve had a pair of Scott ski goggles with amber double lenses, which improve visibility in haze. They weigh 4 ounces. The foam mesh vents above and below the lenses reduce fogging, though the goggles suffer this more than glacier glasses. A wide elasticized, adjustable headband plus thick, soft foam around the rim makes them comfortable to wear. For a few years I stopped carrying them, since I rarely used them. Then I had a horrendous descent down a steep ridge in strong winds and driving, stinging snow that kept blowing behind my glacier glasses so I couldn’t see. Every few minutes I had to stop and clear the glasses. Goggles would have made the descent quicker, safer, and more pleasant. Goggles can be worn over a hat or hood and pushed down around your neck when not needed, which is less risky than pushing them up on your forehead and having them fall off. Bollé, Jones, Cébé, Smith, and Scott all make good goggles.

All too often, every rock within a few hundred yards of a popular campsite sprouts ragged pink and white toilet paper around its edges. Aside from turning beautiful places into sordid outdoor privies, unthinking toilet siting and waste disposal create a health hazard—feces can pollute water sources. As a result, land-management agencies sometimes provide outhouses and deep toilet pits at popular destinations. Mount Whitney, the highest peak in the lower forty-eight states, has one on its summit.

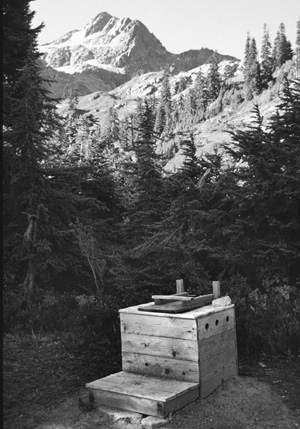

Outhouse sign. Where there are outhouses you should always use them.

Outhouses are obtrusive and detract from the feeling of wilderness. Careful sanitation techniques can ensure that no more need be built. Good methods prevent water contamination, speed decomposition, and shield humans and animals from contact with waste.

To prevent water contamination, always site toilets at least 200 feet (70 paces) from any water. Heading uphill is usually a good way to achieve this. Look for somewhere comfortable to squat that is out of sight of trails, campsites, and anywhere people might see you. The best way to achieve rapid decomposition is to leave waste on the surface, where the sun and air soon break it down. But this isn’t a good idea in popular areas and is now not recommended anywhere. As well as being unsightly, it attracts insects and animals. Instead, dig small individual catholes 6 to 8 inches deep, in dark organic soil if possible, since this is rich in the bacteria that break down feces. After you’ve finished, break feces up with a stick and mix them with the soil—they decompose more quickly—then fill in the hole and camouflage it. Feces don’t decompose very rapidly in catholes, so where they are sited is important. Ideally they should be on a rise where water won’t flow and wash the feces downstream. A site that catches the sun is good too, since heat speeds up decomposition.

A pit toilet with a view.

You need a small trowel for digging catholes. I carry a 2-ounce orange plastic Coghlan’s Backpacker’s Trowel in a pack pocket. An alternative is the Eastman Outdoors Little Jon Shovel, which weighs 2.8 ounces and has a hollow handle that holds eighty-five sheets of toilet paper. These plastic trowels make digging catholes easy, but they can and do break, especially in rocky ground. Somewhat heavier at 6.5 ounces but much stronger is the U-Dig-It Stainless Steel Hand Shovel with folding handle.

Large groups should not dig big latrines unless there are limited cathole sites or the group is staying at a site for more than one night. The idea is to disperse rather than concentrate waste. If you do dig a latrine, it should be sited as for a cathole.

There remains the problem of toilet paper. I use a standard white roll with the cardboard tube removed—3.5 ounces. (Avoid colored paper because the dyes can pollute.) Although toilet paper seems fragile, it is amazingly resilient and shouldn’t be left to decorate the wilderness. You have two options—burning it or packing it out. The first should never be used when there is any fire risk, however minute. If you have a campfire, though, it makes sense to burn used toilet paper in it. Mostly you should pack it out in doubled plastic bags. In some areas where campfires are banned, such as Grand Canyon National Park, this is required. As long as the bags are kept sealed, used paper doesn’t smell. The paper should be disposed of in a toilet, the plastic bags in a garbage can. Women also should pack out used tampons unless they can be burned, which requires a very hot fire. If tampons are buried, animals will dig them up. More specific advice for women, plus a lot of good general advice on backcountry toilet practices, can be found in Kathleen Meyer’s humorous How to Shit in the Woods.

For those prepared to try them, natural alternatives to toilet paper include sand, grass, large leaves, and even snow. The last, I can assure you, is less unpleasant than it sounds.

Deep snow presents a problem. Digging a cathole just means the contents will appear on the surface when the snow melts. This is still the best method in little visited areas, however. It’s even more important to be sure catholes are sited where no one is likely to find them and in places where no one will camp, such as narrow ridge tops and thick bushes or stands of trees. In really remote areas feces can be left on the surface, since then they’ll start to decompose straightaway. In both cases check where water flows in the summer—by observation and from the map—and try to site your toilet well away from any creeks. In popular areas consider packing feces out. If they’re frozen, this is less unpleasant than it sounds. The Phillips Environmental Wag Bag, designed for the removal of feces, could make it more acceptable. This consists of a waste bag, a zip-closed storage bag, toilet paper, and hand sanitizer. The biodegradable waste bag is puncture proof and contains an environmentally friendly gelling agent with the wonderful name of Pooh-Powder that turns feces into a stable gel.

Urination is a matter of less concern. Urine is sterile, so it doesn’t matter too much where you pee. However, the salts in urine may attract animals, so it’s best to pee on bare ground rather than vegetation that could be damaged by animals’ licking the salt off the leaves. In snow urine leaves unsightly yellow stains that should be covered up.

The only time urination becomes a problem is when you wake in the middle of a cold, stormy night and are faced with crawling out of your sleeping bag, donning clothes, and venturing out into the wet and wind. The answer is to pee into a wide-mouthed plastic bottle. With practice, men can do this easily. I use a cheap plastic pint bottle (2 ounces) with a green screw top that clearly distinguishes it from my water bottles. I’ve marked it with a large letter P as well. I carry it mainly in winter and spring. A pee bottle could also be useful in summer when biting insects are around, since otherwise you’d have to get dressed before leaving the tent. (Not to do so is to invite disaster. On a course I led, a student left his tent one night clad in just a T-shirt, despite warnings. He was out less than a minute, but in the morning he emerged covered with no-see-um bites from the waist down.)

For women pee bottles clearly present problems. Two devices may help. The Lady J Adapter fits into the mouth of a shaped bottle called the Little John Portable Urinal and can be used in a tent. An alternative is Sani-fem’s Freshette, a close-fitting plastic funnel with attached tube that can be used with any bottle.

It’s an unusual trip when something doesn’t need repairing, or at least tinkering with, so I always carry a small repair kit in a stuff sack. Although the contents vary from trip to trip, the weight hovers around 4 ounces. Repair kits for specific items such as the stove and the Therm-a-Rest travel in this bag.

The most-used item in the kit is the waterproof, adhesive-backed ripstop nylon tape, which patches everything from clothing to fly sheets. You can buy this in rolls, but I prefer the strips that come stapled to a card. Most types have four to six different colored strips of nylon, measure 3 by 9 inches, and weigh about an ounce. There are several brands, including Kenyon and Coghlan’s. When applying a patch, round the edges so it won’t peel off, and patch both sides of the hole if possible. Patches can be reinforced with adhesive around the edges. I carry a small tube of seam sealant or epoxy for this purpose, or I use the glue that comes with the Therm-a-Rest repair kit.

An alternative to sticky ripstop tape is duct tape, the mainstay of many repair kits. I carry strips of duct tape wrapped around a small piece of wood, and have used it to hold together cracked pack frames, split ski tips, broken tent poles, and other items. On clothing, sleeping bags, and tent fabrics, however, I find sticky nylon tape better because it is more flexible and stays on longer. Duct tape leaves a sticky residue too. Professional repairers and cleaners hate it.

Large pieces of nylon are useful for patching bigger tears and holes. Since repair swatches often come with tents and packs, I’ve built up a collection from which I usually take two or three sheets of different weights, including a noncoated one for inner tent repair; the biggest swatch measures 12 by 18 inches. They have a combined weight of half an ounce.

Also in the repair kit goes a selection of rubber bands. These have many obvious uses, and some not so obvious. A length of shock cord tied in a loop makes an extra-strong rubber band. Any detachable pack straps not in use also end up in the repair bag—perhaps “oddities kit” would be a better name.

My sewing kit consists of a sewing awl, two heavy-duty sewing machine needles, two buttons, two safety pins, a cotter pin (for rethreading draw-cords), two ordinary sewing needles, and several weights of strong thread packed in a small zippered nylon bag. The total weight is only 1.5 ounces, yet with this kit I can repair everything from packs to pants.

For details of how to repair outdoor gear see Annie and Dave Getchell’s excellent book The Essential Outdoor Gear Manual.

The final item in the repair bag—nylon cord—deserves a section of its own because it’s so useful. I use parachute cord (paracord), which comes in 50-foot lengths with a breaking strength of 350 pounds at a weight of 4 ounces per hank. Over the years I’ve used it for pitching a tarp, making extra tent guy-lines, bearbagging food, replacing boot laces, hanging out wet gear, tying items to my pack (wet socks, crampons, ice ax), fashioning a swami belt (made by wrapping the cord around and around your waist) for use with a carabiner and rope for river crossings, lashing a broken pack frame, lowering a pack down and pulling it up short steep cliffs or slopes (with the cord fed around my back, a tree, or a rock—not hand over hand), and anchoring gaiters and hats. The ends of cut nylon cord must be fused with heat or they’ll fray.

Paracord has been around for decades. Now there is a lighter and stronger alternative in Spectra cord. Fifty feet of Bozeman Mountain Works’ AirCore Plus weighs 1.8 ounces and has a breaking strength of 1,109 pounds. And for real weight cutting, the extremely thin AirCore 1 weighs just 0.2 ounce per 50 feet and has a breaking strength of 188 pounds. Cord this thin is fine for guylines (though it’s so thin it can be difficult to knot), but not for bearbagging or other heavy-duty uses. Air-Core Plus sounds excellent, though. Next time I buy cord I’ll get some.

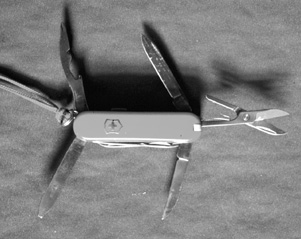

A small knife is useful for backpacking, but you don’t need a large, heavy sheath knife or “survival” knife for most purposes. I mostly use a blade for opening food packets and slicing cheese, as well as cutting cord and other items. Scissors are the other tool I use frequently, and it’s convenient and lighter to have these on a knife.

Victorinox Classic Swiss Army Knife.

Small pocketknives, especially the classic Swiss Army Knife (SAK), are the standard backpacking tools. Beware of inferior imitations—the only genuine brands are Wenger and Victorinox. There’s a huge range of models with just about every blade or tool you could want.

For years I’ve used the Victorinox Climber, which weighs 2.5 ounces and has two blades, scissors, can opener/screwdriver, bottle opener/screwdriver, corkscrew, tweezers, and toothpick, plus a couple of those slightly strange tools whose usefulness is unclear—a reamer/punch and a multipurpose hook. If I’m really trying to keep the weight down I carry a tiny Victorinox Classic, which weighs 0.7 ounce and has a small blade, a file/screwdriver, scissors, tweezers, and a toothpick. I was dubious about such a tiny knife at first but was pleasantly surprised to discover that it did everything I wanted from a knife.

Recently I’ve been fascinated by the Altimeter model (3.25 ounces). Just when it seemed that Victorinox really couldn’t add anything more to an SAK, up pops one with an altimeter and thermometer built into the handle, displayed on a tiny digital screen. (See Chapter 9 for information on altimeters.) It has the same blades as the Climber, though with a third tiny screwdriver but no tweezers (I replaced the toothpick with the tweezers from my Classic).

I have sometimes carried other knives such as the 7.5-inch French Opinel folding knife with wooden handle and single locking carbon steel blade. It weighs just 1.75 ounces, and the blade holds an edge better than the stainless steel Swiss Army ones. Recently I’ve been tempted by the Tool Logic SL3, which has a 3-inch blade and weighs 2.75 ounces, because it has a FireSteel in the handle and a notch on the blade for drawing it across (see page 314). There are many other small knives and folding multitools around: Gerber, Schrade, Kershaw, SOG, Buck, and Leatherman are some of the other quality ones. Most of the multitools have pliers, which I rarely need, but not scissors, which I use regularly.

Keeping your knife blades sharp is important. I don’t carry a sharpener, however, because the best place to sharpen them is at home.

If you are injured or become seriously ill in the wilderness, you need to alert other people and rescuers to your whereabouts. Displaying a bright item of clothing or gear is one way to do this. Your headlamp or flashlight can be used for sending signals, in daylight as well as at night. Noise can attract attention, of course, and I always carry a plastic whistle. For years this was a Storm Whistle (0.8 ounce), from the All-Weather Whistle Company of St. Louis, which is said to be one of the loudest, reaching almost 95 decibels. I’ve passed this whistle on to my stepdaughter and replaced it with a Fox 40 Classic (0.5 ounce with lanyard). I’ve never used it, but it’s always there just in case. Whether you use light or sound, the recognized distress signal is six regular flashes or blasts, pause, then six more.

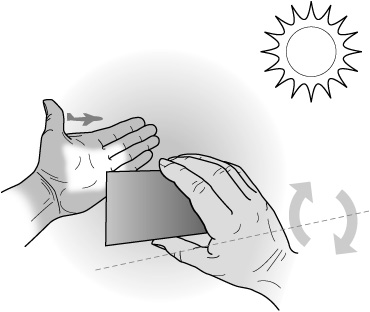

Using an ordinary mirror as a signal mirror. Capture the sun’s reflection in your palm, then flick the mirror up and down to send a signal to approaching aircraft.

In most remote areas, initial searches are likely to be made by aircraft, so you need to be seen from above and from afar. A fire, especially with wet vegetation added, should create enough smoke to be easily seen. Ideally, you should light three fires in the form of a triangle, an internationally recognized distress signal. Flares are quicker and simpler to use, and various packs are sold. I’ve never carried flares, but they would have been reassuring at times during the Canadian Rockies and Yukon walks. Carrying several small flares seems to make more sense than one big one; larger flares last longer, but unless you carry several, you have only one chance to draw attention to your plight. Packs of six to eight waterproof miniflares with a projector pen for one-handed operation weigh only 8 ounces or so. The flares reach a height of about 250 feet and last six seconds.

Signaling mirror with sighting hole.

Flares need to be handled and used carefully. A much safer alternative is a strobe light. Some LED lights can be set to flash regularly.

Mirrors can be used for signaling, though obviously only in sunlight. Plastic ones are cheap and light (0.5 ounce upward). I have an MPI Safe Signal mirror weighing 1.25 ounces. It’s made from polycarbonate and is silver on one side and red on the other, for use with a flashlight at night (the effect is very bright). I sometimes carry it in my “office” pouch (see below). Any shiny reflective object, such as aluminum foil (stove windscreen), a polished pan base, a watch face, a camera lens, or even a knife blade could be used instead.

If you are in open terrain and have no other signal devices, spreading light- and bright-colored clothing and gear out on the ground could help rescuers locate you.

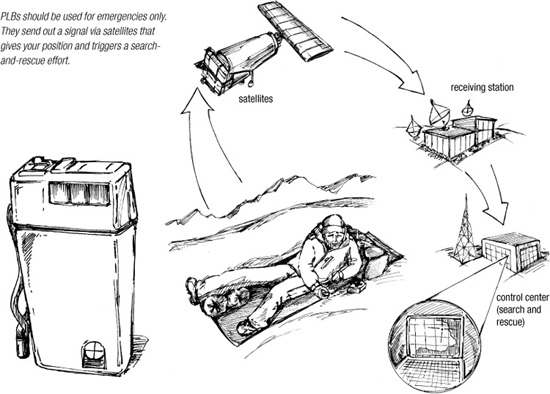

Personal locator beacons (PLBs) have been around for decades and are standard safety items on boats and planes. They were illegal for land use in the United States until July 2003, however. PLBs send out a signal via satellites that gives your position and triggers a search-and-rescue (SAR) effort. They are for emergencies only and should never be used unless you’re in a life-or-death situation. I’ve carried PLBs twice. The first time was on my 1,000-mile solo hike in the Yukon where I was loaned one, unofficially, by local people concerned for my safety in remote wilderness. “If it goes off by accident, jump over a cliff before the rescue teams arrive,” I was told, only half jokingly. It lay mostly forgotten in a pack pocket for the next three and a half months. The second occasion was when I led a skiing expedition in Greenland. In this case the PLB was not only official but also a legal requirement. Both these trips were into very remote, little visited country where an accident or illness could have been fatal. Whether PLBs are needed in most backcountry areas, which are much more accessible, is debatable. They will undoubtedly save lives and make the work of SAR teams easier and safer. However, as with cell phones, there is a danger that some people will regard PLBs as substitutes for skill. They could easily be misused too, with people using them for minor inconveniences or concerns that don’t warrant calling out a rescue. At present the very high cost will probably limit the number of people who carry them but as with all electronics prices are likely to fall. Whether or not to carry one is a personal decision but they should only be used when absolutely necessary.

Cell phone in waterproof Ortlieb case.

The PLBs I carried were designed for carrying on aircraft, and were large and heavy. Since their legalization in the United States, lightweight models suitable for backpacking have appeared. The lightest is the McMurdo FastFind PLB, which weighs 9 ounces. The basic unit can locate the signaler to within half a mile. The FastFind Plus has a GPS receiver built in and is accurate to within 100 yards. A little heavier at 12 ounces is the ACR Terrafix. Again there are versions with and without GPS. All PLBs have to be able to broadcast continuously for 24 hours and work down to −4°F (−20°C). This makes for a hefty battery, which makes up most of the weight.

An increasing number of hikers carry cell phones, though many backpackers feel they have no place in the wilderness and detract from the reasons for being there. Their usefulness in an emergency is undeniable, and many people have been rescued quickly because they had phones. However, too many people use their phones for what can only be regarded as frivolous reasons, such as asking for advice on routes and where to find water to drink. Some people seem to think a phone is a substitute for wilderness skills—if you get lost, you can just make a call. This is irresponsible and puts great pressure on rangers and rescue services. Phones should be used only in real emergencies where you need outside help. Relying on a phone is unwise anyway: they can break, and batteries can fade. Also, they’re unlikely to get a signal in remote areas, deep canyons, and dense forests. If you do bring one and want to use it other than in an emergency, do so away from others. It can be very irritating to reach a summit or a pass and hear someone talking on a phone. Think, too, about how much a phone detaches you from the wilderness you’ve come to experience.

If you’re alone and suffer an immobilizing injury or illness, all you can do is make yourself as comfortable as possible, send out signals, and hope someone will respond. In popular areas and on trails, attracting attention shouldn’t be too difficult, but in less-frequented places and when traveling cross-country you may be totally dependent on those who have details of your route to report you missing when you don’t check in as arranged.

Groups should send for help if they can’t handle the situation themselves. It’s important that whoever goes has all the necessary information: the location of the injured person(s), compass bearings, details of local features that may help rescuers find the place, the nature of the terrain, the time of the accident, a description of any injuries, and the size and experience of the group. All this should be written down so that important details aren’t forgotten or distorted. Once out of the wilderness, the messenger should contact the local law enforcement, park, or forest service office.

Most mountain rescue teams are made up of local volunteers. These people give up their time to help those in need, often at great personal risk and cost. If you need their services, make a generous donation to the organization afterward; they are not government funded.

Roped climbing is for mountaineers. However, there are rare times when backpackers need a short length of rope for protection on steep terrain. Full-weight climbing rope isn’t necessary; I’ve found quarter-inch line with a breaking strain of 2,200 to 3,400 pounds perfectly adequate. A 60- to 65-foot length (the shortest that’s much use) weighs 20 ounces or so. For a rope to be useful, you need to know how to set up belays, how to tie on, and how to handle it safely. This is best learned from an experienced climbing friend or by taking a course. Ropes need proper care. They should be stored out of direct sunlight and away from chemicals. A car seat or trunk is not a good place to keep ropes. Even with minimum use and careful storage, ropes deteriorate and should be replaced every four or five years. I’ve mostly carried ropes for glacier crossings during ski tours. These have been full-weight, full-length climbing ropes. I haven’t carried a rope when hiking for nearly twenty years.

In deep snow, a shovel is both an emergency tool and a functional item. The emergency uses range from digging a shelter to digging out avalanche victims. More mundane uses are for leveling tent platforms, digging out buried tents, clearing snow from doorways, digging through snow to running water, collecting snow to melt for water, supporting the stove, and many other purposes. I find a snow shovel essential in snowbound terrain. They come with either plastic or metal blades. I prefer metal; plastic blades won’t cut through hard-packed snow or ice. There are many models, usually with detachable blades. Voilé, Life-Link, Backcountry Access (BCA), Ascension, and Safety on Snow (SOS) make good snow shovels. I have a BCA Tour Shovel with a large aluminum blade that weighs 18 ounces.

I once carried a length of fishing line and a few hooks and weights on a long wilderness trip, in case I ran out of food. I duly ran short of food, and on several nights I put out a line with baited hooks. On each successive morning I pulled it in empty. Experienced anglers probably would have more success, and if you’re one, I’m sure it’s worthwhile to take some lightweight fishing tackle, depending on where you’re headed.

Route finding as a skill is discussed in Chapter 9, and it therefore makes sense to leave any detailed discussion of equipment until then. Here I will mention the effect navigation can have on your load. On any trip a compass and a map, weighing between 1 and 4 ounces, will be the minimum gear you’ll need. On most trips you’ll need more than one map, and you may carry a trail guide as well. On trips of two weeks and longer, I usually end up with 25 to 35 ounces of maps and guides. In remote, trailless country, you might want a GPS receiver, which adds at least 3 ounces. Chapter 9 contains details of these.

I carry a notebook, pen, and pencil on every trip. Along with a paperback book, maps, and various papers, they live in a small pouch or stuff sack. There are many suitable pouches, mostly containing several compartments and designed to be fastened to pack hipbelts or shoulder straps. Weights range from a few ounces to a pound or more. I use a simple single-compartment waterproof nylon pouch with a Velcro closure that weighs an ounce. If I have books and maps that won’t fit in this flat pouch, I carry them in a small waterproof stuff sack. My office lives in a pack pocket where it is easily accessible.

Keeping a journal on a walk is perhaps the best way of making a record for the future. I’ve always kept journals, long before I began writing for anyone other than myself, and by reading them I can spend hours reliving a trip I’d almost forgotten. In order to record as much as possible, I try to write in my journal every day, often making a few notes over breakfast and at stops during the day, then more extensive ones during the evening. This is difficult enough to do on solo trips; when I’m with companions, I’m lucky if I write in it every other day. I use single journals for long trips (over two weeks) and an annual journal for other trips.

There are masses of suitable notebooks. Those with tear-out pages are very light, but I prefer bound ones. I mostly use oilskin notebooks with water-resistant black covers. There are various brands, such as Moleskin Pocket Notebooks from Dick Blick Art Materials and Blueline Memo books, which are made from recycled paper. A 4-by-6-inch notebook with 190 pages weighs about 4 ounces. If you want to make notes when the weather’s wet, waterproof notebooks are available from Rite in the Rain. The 4-by-6-inch All-Weather Pocket Journal has 50 detachable sheets and weighs 3 ounces. The bound 4-by-6.5-inch Adventure Travel Journal has 78 sheets plus 15 pages of reference material. To write on the waterproof paper you need a pencil, a Space Pen, or Rite in the Rain’s All-Weather Pen. These notebooks are waterproof, but they’re also expensive. I have a Pocket Journal, which I use only in really wet weather.

In my notebook I keep route plans, addresses of people at home and people I meet along the way, lists of how far I go each day and where I camp, and any other information I may need or collect along the way. Looking at my Canadian Rockies journal, I see I kept records of my resting pulse rate (which ranged between 44 and 56) and how much fuel my stove used (ten to fourteen days per quart). I also made shopping lists and, toward the end, a calendar on which I crossed off the days. (There was a reason for this—buses at the finish ran only three times a week.) Such trivia may not seem worth recording, but for me they bring back the reality of a trip very strongly.

I usually carry at least two Space Pens, which have waterproof ink in case my notebook gets wet, and usually a refillable pencil as well. They weigh half an ounce each.

Some hikers now use small electronic notebooks, often ones that will connect to a modem so they can send e-mail and update Web logs either via their cell phones or when they reach a standard phone. I prefer my notebook. I did try a PDA to see what it was like, but I found the tiny keyboard difficult to use. Also, I sit in front of a computer for too long at home working. Out in the backcountry I prefer not to do so. But such portable devices are there for those who want them.

The documents you need to carry on a trip can amount to quite a collection, though they never weigh much. On trips close to home, you may need none. On any trip abroad you’ll need your passport, perhaps a visa and hiking permit, and insurance documents. It’s wise to carry airline or other travel tickets too. It’s useful to have some form of identification such as a driver’s license in case of emergency. While walking I keep my papers sealed in a plastic bag in the recesses of my “office.” Trail permits, if required, also go in a plastic bag, but I often carry them in a pocket or my fanny pack so they’re ready if I meet a ranger.