Guided by reason

We have many reasons to dismiss the ideal of rationality as an impersonal, impartial sovereign that will lead us to the truth. As we have seen, reason is unable to determine for us what we ought to believe about the big issues of religion and to a lesser extent about science. Rational agents may agree about a great deal but there is always an element of judgement in drawing conclusions that cannot be reduced to anything like a logical algorithm. The way we think is deeply affected by our own personal dispositions, commitments and values. Many non-deliberative factors influence our reasoning and it would be unrealistic to believe we could ever fully overcome them.

If we imagined reason to be our absolute ruler, then it would be right to use considerations like these to dethrone it. But to demote our erstwhile sovereign is not the same as to decapitate it. To work out what best to do with our not-so-omnipotent leader we need to think a little about our assumptions of what the leadership role entails.

Our problem is that we have looked to reason to provide guidance from a privileged, external, impartial standpoint. This is a form of rule that is heteronomous: coming from outside ourselves. Reason is, if not quite personified, then at the very least ‘reified’: turned into an abstract thing with a life of its own. On this conception, all we need to do is find out what reason demands and follow it. But we can’t do that, because reason is a human faculty that is shaped and limited by its hosts. We can formulate laws of logic that exist outside of us and even come up with some principles of inductive reasoning, but in order actually to use reason we cannot leave us reasoners behind.

Reason therefore has to be autonomous, not heteronomous. It has to be something we use for ourselves and fully own, taking responsibility for how we use it. There is, however, something almost paradoxical about this, which Kant’s account of the autonomy of reason illustrates. Kant argued that when we reason we must never submit to an external authority but must think for ourselves. Only this is appropriate to the dignity of the human individual. At the same time, however, Kant believed that if we think truly for ourselves, we will come to see what reason demands and freely submit to it. So whereas the person who accepts 1 +1 = 2 because a teacher says so is thinking heteronomously, someone who understands why the sum must be so is thinking autonomously. But in so doing, one form of obedience is being substituted for another: we bow down to reason, not to those who tell us what to think.

Kant’s autonomy could therefore be seen as another form of heteronomy, in which the external authority is not human but the pure, abstract nature of reason itself. The autonomy of reason I propose goes further. We have to accept that reason does not stand outside ourselves but must work within us. Reason is not a guide we can simply entrust ourselves to, expecting it to take us along the road to truth without our having to make any decisions at all. Reason is the kind of inner guide that informs but does not dictate our decision-making, rather than an external one that makes our decisions for us. Nevertheless, Kant was on to something, because there is a sense in which reason does require us to accept heteronomous demands. Our guide is useless if it is merely a form of self-determination which pays no attention to the brute reality of the external world. When we are presented with arguments or given reasons for belief, the way things really are must determine whether they are rational or not. In short, reason is nothing if it does not aspire to objectivity. That is the heteronomous aspect of reason and it brings us to the heart of my account of rationality: rational argument should be defined as the giving of objective reasons for belief.1

1. Objectivity

Given what I have argued so far, the demand for objectivity might appear to set too high a bar for rationality. Doesn’t objectivity require precisely the kind of impersonal certainty that I have consistently argued is beyond us? But just as I am arguing that we need a more modest conception of rationality, so our concept of objectivity must not be so austere as to be beyond us. As it happens, we have already available just the kind of realistic conception of objectivity we need, one developed by Thomas Nagel.2

Nagel describes an unattainable ideal of objectivity as the tautological ‘view from nowhere’. Described as such, its impossibility is self-evident, but of course it is not always so conceived. Objectivity has been more typically described as taking a ‘God’s eye view’, which is not obviously paradoxical, even though it is so heavily metaphorical that it is not at all clear what a literal translation of the idea would look like.

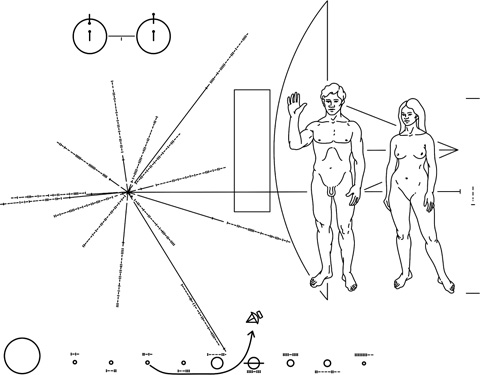

The most credible version of the kind of strong objectivity Nagel rejects does away with the metaphor of ‘views’ or ‘perspectives’. An objective fact or account would be one that was true for anyone at any time, regardless of what particular perspective on the universe they take. Perhaps the most ambitious human attempt to express such objective truths are the gold-anodised aluminium plaques sent on two Pioneer spacecraft in 1972 and 1973. These were the first human-made machines to be sent beyond the solar system. The idea was that if the craft were intercepted by aliens, the plaques would enable them to understand who we are and where we came from.

The designers of the plaque were trying to find what Bernard Williams called ‘concepts and styles of representation which are minimally dependent on our own or any other creature’s peculiar ways of apprehending the world’,3 and hence to communicate in a truly objective way. Human language wouldn’t do, since it would be incomprehensible even to aliens who had oral and written languages like ours, let alone any that communicated in different, perhaps unimaginable ways. So instead, they settled on images, diagrams and mathematics. A man and woman were pictured, along with a schematic map of the universe and a diagram representing the hyperfine transition of the hydrogen atom. Binary numbers accompanied the diagrams.

The reasoning behind this was that, however different aliens might be from us, if intelligent, they must be familiar with hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe, and they must also have some conception of mathematics, which appears to be fundamental to understanding nature. Although they may have different ways of representing these things, there must be a strong chance that they would be able to make sense of our entirely schematic representations of them.

Whether aliens could make sense of the plaques is moot. The question as to why they would know raising an open palm is a symbol of welcome is only the most obvious problem. The diagram of the universe, for example, includes an arrow. The meaning of this appears so self-evident to us that we forget that its ubiquity today depends entirely on the fact that it was initially recognisable as an analogue of the real arrows of hunters. The idea that any species would understand a mark such as ‘⃗’ to be a directional pointer without this human history seems baseless. There is nothing which makes ‘⃗’ more objectively a pointer than ‘1’, ‘!’ or ‘Y’. Even more fundamentally, why should we assume that aliens would know that the visual markers were important at all? If they did not have eyes, they might not even notice what to us seems obviously to be ‘on’ the plaque.

Still, although we might have failed to come up with a truly objective way of communicating, isn’t the information on the plaque still a decent shot at objectivity? After all, hydrogen is the most fundamental element in the universe and mathematics is universal. There are two problems with this response. First of all, it is really difficult to be completely confident about what the most objective view of the universe will look like. With hydrogen, for example, we already know that elements are far from the most fundamental building blocks. Who knows whether to an advanced civilisation dividing matter (another concept they may have done away with) according to elements is as primitive and misguided as dividing the human body up into the four humours of black bile, yellow bile, phlegm and blood?

Second, there is a sense in which this is beside the point. Even if the truths we latch on to are indeed objective, they are always framed within our human ways of understanding, by our language and our senses. This means even objective truths are never conceived in their pure, objective state, but always as seen through the human lens. Truth has to be seen from some perspective or other, even if it is in itself purely objective.

But rather than despair that this makes absolute objectivity unattainable, we should rather ask whether it makes sense to talk of something less than absolute objectivity. This is where Nagel’s account comes in. For Nagel, knowledge does not divide neatly between the either/or of ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’. Rather, there is a spectrum, with absolute objectivity and subjectivity at opposite ends, and degrees of each in between.

Our understanding is subjective to the extent that it depends on idiosyncratic features of our viewpoint, reasoning, conceptual framework or senses. It becomes more objective the less it depends on these factors and the closer it gets to the unachievable ‘view from nowhere’. The value of objectivity is that it takes us away from subjective viewpoints which are more partial, both in the sense of reflecting our biases and preferences and in the sense of invoking a more limited range of reasons and experiences. Understood in this way, we can see how the Pioneer plaques did represent knowledge that was not merely human understanding but had a high degree of objectivity. Perhaps we did not put it in such an objective form that all aliens could comprehend it, but at least they did not need to be human to have a chance of understanding it. So both the content and the means of expression of the plaque achieved a high degree of objectivity.

That is the notion of objectivity we need to use when we say that rational argument is the giving of objective reasons for belief. It entails appealing to reasons which do not depend on others sharing our own particular perspectives in order for them to have force. It does not mean appealing to reasons which are of such a form that any intelligence anywhere would be able to see their force.

One thing that is worth noting at this point is that ‘objective’ is often taken to be synonymous with, or at least implying, ‘true’. This is a mistake. To say an account, reason or observation is objective or subjective is to say something about its character, not its truth value. I can report a fact about my subjective experience truly – for instance, that I perceive a sound to be yellow – and I can report an objective fact falsely, such as the distance between two planets. The degree of objectivity a claim has relates only to the extent to which it does not require a particular perspective to be understood. That is why it is right that we talk of ‘objective truths’ or ‘objective facts’ and don’t merely say that statements are ‘objective’.

Rationality and objectivity are usually seen as natural bedfellows. My suggestion is that their link is more intimate than this. To offer a rational argument just is to provide objective reasons for belief, reasons which can include both evidence and argumentative moves. This is a deliberately catholic definition of rationality. It allows that an argument can be rational but can fail, which is surely right: there is a difference between someone who argues irrationally and one who argues rationally but makes mistakes. It is also broad enough to encapsulate both reason’s deductive and non-deductive aspects, and to appeal to those who think rational argument aims at truth and to those who think there is no such thing as The Truth. I’ll say more about this towards the end of this chapter. First I need to say more about how we recognise those reasons and arguments that are objective. I would argue that they have five key characteristics. They are comprehensible, assessable, defeasible, interest-neutral and compelling.

2. Five characteristics of the objective

(i) Comprehensibility

Art appreciation is usually thought of as quintessentially subjective. Nonetheless, some judgements are clearly more objective than others. Consider, for example, how we might respond to Goya’s painting Perro semihundido (Half-submerged Dog). You could say things such as ‘I like it’ or ‘It makes me feel sad’. These comments don’t tell me anything about the work. If I share your reactions then your remarks just happen to describe how I feel too, but if I don’t they only tell me about how you are feeling. But if I push you, you might say more. You could point to the dog’s eyes and how it seems to express a kind of resigned helplessness, a sense heightened by the way in which the huge wave dominates the picture. You might muse on how depicting a dog deepens the pathos, since we are being made in some sense aware of the helplessness of all living creatures in the face of nature.

In comments like this we get nowhere near to perfect objectivity. Many people would still find themselves unilluminated. Nonetheless, there is clearly a move towards greater objectivity in such remarks. The characteristic feature of objectivity is that it moves from a particular viewpoint to a more general one, one that can be shared. The move from reporting a purely personal reaction to describing features of the work itself and explaining why they provoke such reactions is one such move from the individual to the more general. One key feature of this move is that the terms of explanation offered in the more objective account are in principle comprehensible by more rational agents than are those in a subjective account.

To take another example, a physics which is in principle comprehensible by Martians who lack the typical sensory apparatus of humans is more objective than one that depends upon a specifically human way of experiencing the world. I would conjecture that this kind of increased comprehensibility is a constitutive feature of rational argument. An argument that is in principle comprehensible by any rational agent is more rational than one that is comprehensible only by certain types of rational agent.

This is not to be confused with clarity or difficulty. Theoretical physics is one of the most objective sciences we have, but it is mystifying to the layperson and extremely hard to grasp. To say something is ‘in principle’ comprehensible is not to say everyone has the intelligence, knowledge or application to understand it. ‘In principle’ here means that there are no obstacles to understanding other than intelligence, knowledge and application, obstacles that in the real world might indeed prevent many from ever understanding.

If we think about how we use the term objective more widely, we can see that comprehensibility is at the heart of it. Inspection and assessment of schools and businesses is one clear example. Inspection can be defended as objective when it is perfectly clear to everyone what the criteria are and how they have been assessed. It can be criticised as subjective when there is no way of really knowing what could be done to get a higher mark or avoid being docked points. All other things being equal, the more comprehensible any description or explanation is, the more objective it is.

(ii) Assessability

Comprehensibility is the most basic characteristic of the objective. However, it is not enough that a rational argument is comprehensible by any rational agent. It must also be assessable. If there is no way in principle that others could judge the truth of what is claimed, it remains in the domain of the subjective. As Michael Lynch puts it, objectivity ‘is a matter of openness to evaluation from a common point of view.’4

This is in a sense an extension of the criterion of comprehensibility. Think again of the example of inspection. Criteria like ‘cleanliness’ or ‘good record keeping’ are clear enough for us to understand what they mean in general, but to truly understand them in context you must know how to judge whether they have been met. Knowing how to assess whether the conditions have been met is part and parcel of understanding what the conditions are.

But there are times when we have comprehensibility without assessability. This is one reason why the kind of art appreciation I discussed only reaches a limited degree of objectivity. If I just don’t see resignation in the dog’s eyes, for instance, there is no way of assessing whether I am wrong or you are projecting emotions that aren’t there. My judgements are objective to the extent that they can be understood, but less objective than other kinds of judgement to the extent that there is no clear way of assessing their validity.

There is an another important link between assessability and comprehensibility. One key feature of any objective account is that everything in it is out in the open. Whenever people appeal to inner convictions, esoteric revelations or diktats from authorities they are evading objective scrutiny by keeping key elements of their justification hidden. To give an objective account requires you to hide nothing. This means making your evidence and arguments open to the closest possible examination, in terms that make sure that they can be both understood and assessed by any rational agent.

It might be objected that in invoking the concept of a rational agent in my explanation of what rationality is I am guilty of arguing in a circle. To some extent this is true, but the circularity is not vicious. A rational agent is one who can understand and assess objective arguments, and an objective argument is rational if it can be understood and assessed. These terms all hang together. Words can only be defined using other words, so definitions always end up going round in circles. What one person criticises as circularity another accepts as the holism of language.

The idea that anyone ought to be able to assess claims to objective truth has been a deep assumption of Western philosophy since its origins in ancient Greece. What distinguishes philosophical claims from theological ones is that the philosopher making them does not do so by appeal to any authority other than that of the evidence and arguments themselves. However, it has proven extremely difficult to specify in more detail exactly what distinguishes the assessable from the unassessable. David Hume managed to divide the assessable up ‘into two kinds, to wit, Relations of Ideas, and Matters of Fact’. Relations of ideas are ‘the sciences of Geometry, Algebra, and Arithmetic’, to which we might add formal logic. Claims within these disciplines can be shown to be ‘either intuitively or demonstratively certain’.5 Matters of fact, on the other hand, are shown to be true by experience. Hume, however, says little about how we show this, being mainly concerned with the question of how we establish the relation of cause and effect, upon which ‘all reasonings concerning matter of fact seem to be founded’.

In the early twentieth century, attempts were made to come up with a more robust test for what might pass as a genuine matter of fact, rather than of mere speculation. The so-called logical positivists of the Vienna Circle proposed various versions of the principle of verification, according to which propositions are only meaningful if there is some empirical method of demonstrating their truth. Assessability is thus cashed out as provability. Karl Popper would later come up with a mirror-image alternative according to which hypotheses are scientific if there is some way of testing them such that failing to pass the test would falsify them.

Verificationism and falsificationism both failed, largely because they were seen as self-defeating. There is no way to verify the principle of verification or to falsify the principle of falsification. Therefore by their own criteria they are meaningless or unscientific respectively. However, in rejecting these attempts to put more flesh on the notion of assessability we must not throw out its vitally important bones. Both verificationism and falsification overreached, but they were reaching in the right direction.

A.J. Ayer, who brought his version of logical positivism to Britain, shows how close the school got to the nub of the issue. In the preface to Language, Truth and Logic, he wrote ‘I require of an empirical hypothesis not that it should be conclusively verifiable, but that some possible sense experience should be relevant to the determination of its truth or falsehood. If a putative proposition fails to satisfy this principle, and is not a tautology, then I hold that it is metaphysical and that it is neither true nor false but literally senseless.’6 (In the context of British empiricism at the time, we need to understand ‘sense experience’ as including all empirical evidence gathered from the sciences, which were understood ultimately to rest on observations dependent on sense experience.)

The demand of an empirical hypothesis ‘that some possible sense experience should be relevant to the determination of its truth or falsehood’ is an extremely modest one, far short of the demand for verification or falsification. Had Ayer stuck with this modesty, he would not have got into the terminal difficulties that mean Language, Truth and Logic is now largely ignored, an increasingly rare sight on undergraduate reading lists. But at the same time, the right modesty would also have meant that the book would never have created a storm on publication, making its author one of the pre-eminent philosophers of his generation for the rest of his life.

Ayer’s central mistake was to think that his principle could distinguish between the meaningful and meaningless. This error has two parts. First, a better distinction would be between the objective and subjective. If I say to you that a piece of music, for example, makes me feel like I am floating on air, there may be no way for you to verify or falsify that claim. But that doesn’t make it meaningless. It simply makes it subjective.

The second part of the mistake is to make the distinction binary where it should be spectral. If you accept that what makes a claim meaningful (or objective) is ‘that some possible sense experience should be relevant to the determination of its truth or falsehood’, then it should be obvious that you are not going to be able to draw a sharp line between those claims which meet this test and those that don’t. Even if you could determine a threshold, it would still be the case that some claims are easily settled by sense experience, while for others evidence is relevant to assessing its truth but cannot determine it.

Ayer found himself caught in a classic philosophical predicament. If an idea is too vague it will be dismissed as woolly and hand-waving. Too precise, however, and the logic-choppers will be out to unpick its contradictions and inconsistencies. As Aristotle’s immortal adage states, ‘It is the mark of the trained mind never to expect more precision in the treatment of any subject than the nature of that subject permits’ – nor less, we might add. The Goldilocks state of philosophy is to be precise enough to be saying something substantive but not so precise as to ride roughshod over the complexities and ambiguities of the real world.

Do we have this ‘just right’ understanding of assessability? For my purposes, I think we do. As I will argue in more detail shortly, the conception of rationality I am putting forward here is a minimal one, and in that sense its key terms are place-holders for various more precise ones which different schools might fill out. Furthermore, I have not so much argued that claims to objective truth must be assessable as invited us to attend to the nature of objectivity and notice that it has this feature. It is not for me to legislate here how exactly rational arguments are to be assessed. But it should be obvious that an argument cannot be rational if there is no way of assessing it at all. The only a priori restriction on the types of assessability that are admissible is that they should be methods of assessment which are in principle employable by any rational agent.

(iii) Defeasibility

Popper also got close to the truth with his principle of falsification. Once again, however, the mistake was to over-specify something which, if stated in more general terms, should be uncontroversial.

Popper’s central insight, still widely accepted by scientists today, is that if a hypothesis is genuinely scientific then other scientists must be able to conduct experiments to test it. These experiments might not be able to prove beyond all doubt that the theory is correct, but there are possible experimental results which would show that it is false. To give a simple example, the hypothesis that you cannot transform base metal into gold can never be decisively verified by repeated failures to achieve just this transformation. An experiment that did turn lead into gold, however, would show it to be false.

As a mark of a rational argument, falsification has various problems. First of all, Popper intended it as a criterion for demarcating between science and non-science. So even if the principle works, it does not allow us to to distinguish between the rational and the non-rational, unless we make the further claim that the only form of rational discourse is the scientific one. This is impossible, since such a claim would not be a scientific claim but a philosophical one, and so would be self-refuting.

Second, it is unclear that all scientific claims are actually falsifiable. Hilary Putnam, for example, has argued that ‘The Law of Universal Gravitation is not strongly falsifiable at all; yet it is surely a paradigm of scientific theory.’7 How can this be so? For Popper, falsifiability is possible because theories imply predictions, and we can see if these predictions are borne out or not. For example, Einstein’s theory of general relativity predicted that light does not travel in a perfectly straight line. On 29 May 1919, Arthur Eddington performed an experiment during a total solar eclipse to test this. The Astronomer Royal, Frank Watson Dyson, had realised that the sun would cross the Hyades star cluster during the eclipse, and so the light from these stars would have to pass through the sun’s gravitational field, which Einstein’s theory predicted would bend their course. Because of the eclipse, however, they would be visible. By comparing the apparent position of the stars at this moment with their true position, Eddington was able to show that the light had indeed bent.

But had the experiment not detected the bending, would this have disproved Einstein’s theory? Other failures to confirm predictions in the history of science suggest not. Often experiments do contradict existing findings, but they are not automatically assumed to disprove them. The possibility often remains open that there was something wrong in the experimental design or that some false assumptions have been made. Putnam cites the example of the orbit of Mercury, which was not completely explained by Newton’s theory. But this did not lead to Newton’s theories being rejected. Rather, Mercury was set aside as an anomaly. This kind of toleration of unexplained anomalies is not untypical in science.

According to Putnam, one reason for this is that ‘Theories do not imply predictions’ in the straightforward way Popper believed. ‘It is only the conjunction of theory with certain “auxiliary statements” (A.S.) that, in general, implies a prediction,’ he says. This means ‘we cannot regard a false prediction as definitively falsifying a theory’ since there is always some uncertainty of the status of the auxiliary statements and their link with the theory being tested.

As with assessability and verification, we need to make sure we do not throw out the baby with the bathwater, the baby in this instance being defeasibility. A rational argument is always in principle defeasible – open to revision or rejection – by public criteria of argument and evidence. I think this is just a corollary of the criteria of comprehensibility and assessability. To give a rational argument is to say that others can understand and assess it, and this leaves open the possibility that their assessment might be negative or that their understanding might be superior to one’s own. It certainly seems contrary to the spirit of rational inquiry to rule out the possibility that what one has decided is true could not possibly be false. And even if there were some indefeasible rational arguments, they would form a very narrow set of non-empirical a priori tenets.

Defeasibility is a property of all propositions with any degree of objectivity, however small. Think, for instance, of someone who insists that Goya’s Perro semihundido was the greatest painting of the nineteenth century. Such a person could reasonably maintain that this is just a matter of opinion and is not intended as an objective claim. Nonetheless, if they accept that there is any sense at all in which the claim rests on some objective judgements about the work, it would be indefensible to make it indefeasible. At the every least one should be open to the possibility of being persuaded that another work is superior. Whenever any claim involves something that is assessable by others as well as ourselves, we ought to keep it open to refutation or revision, no matter how certain we are that something is true, no matter how impossible we find it to imagine its refutation.

(iv) Interest-neutrality

Imagine a deranged super-villain who is on a mission to defeat the forces of rationality. He kidnaps a philosopher and is determined to make her sincerely believe something irrational. So he says that he will destroy the Earth unless she is able to say with sincerity that 1 + 1 = 3 and pass a lie detector test while doing so. Our philosopher thinks hard and realises that there are in fact assessable, comprehensible and defeasible reasons for her to believe that 1 + 1 = 3, since believing this is the only way to save the universe. Do we not then here have objective reasons to believe something that is false? And given that I define rational argument as the giving of objective reasons for belief, does that not also mean that there can be rational arguments to believe something false?

The question is likely to provoke contradictory responses. On the one hand, it does seem undeniable that in such circumstances it is rational to believe a falsehood – if you can make yourself do so. On the other, it might seem equally undeniable that rational arguments ought to lead us towards the truth, rather than to what is merely expedient.

The tension is resolved by attending to an ambiguity in the notion of rationality. Rationality can be used in the service of an end or as an end in itself. Call the former kind practical rationality. If our kidnapped philosopher has a desire, interest or value which favours the universe continuing to exist, then it is in an important sense rational for her to (at least try to) believe sincerely that 1 + 1 = 3. But we can easily see that this kind of practical rational ground for belief is very different from the usual rational grounds for believing that 1 + 1 = 2. It does not provide a rational argument to believe that 1 + 1 = 3, but a rational argument why it is prudent to believe 1 + 1 = 3. Because such practical reasons appeal to our desires, values and interests, they are less objective than ones which make no reference to the particular interests, values and desires of living creatures.

Practical rationality, which involves what we ought to believe, given our goals and values, can therefore be contrasted with what I’m going to call epistemic rationality, which solely involves what we ought to believe if we set aside our goals and values. Epistemic rationality needs more than assessable, comprehensible and defeasible reasons for belief; it also needs its reasons to be interest-neutral. Any reasons which appeal to what people desire are not interest-neutral, since they only have any purchase if we think that people’s desires are a reason for doing something.

This interest-neutrality of rational argument is central, since the whole point of a rational argument is that it does not resist brute reality and cannot be bent at will. This does not imply any metaphysical commitments concerning the real existence of an external physical world. (In fact, it is essential that our conception of rationality is free from such commitments, since it is by means of rational argument that we attempt to determine which metaphysical stance it is appropriate to take.) Accepting the resistance of an objective, rational account of the world to our will is simply a precondition for any rational inquiry into the nature of that world, whatever its ultimate nature.

Although the demands of practical rationality might ultimately conflict with those of epistemic rationality, it is important to notice that practical rationality rests on epistemic rationality. Consider our kidnapped philosopher again. In order to conclude that from a practical point of view she ought to believe that 1 + 1 = 3, it is important that all the data she uses to base this conclusion on are supported by the proper use of epistemic rationality. In other words, her reasons for believing that the villain will blow up the world and that she must pass the lie detector test must be of such a kind that any rational agent should accept them. In order to make the right decision, she must assess the evidence in an interest-neutral way, and only then decide what she ought to do in order to serve the interests she takes to be most important. In this case, that means taking the survival of the planet as being more important than preserving a small corner of true belief.

We can now see clearly why the apparent paradox that it can sometimes be rational to believe what is irrational is no paradox at all. A better description is that it can sometimes be practically rational to believe what is epistemically irrational, because epistemic rationality is interest-neutral but practical rationality is not. But it cannot be stressed enough that practical rationality is not an entirely different system. Practical rationality must work on the basis of epistemic rationality.

Having made the distinction, I want to set aside practical rationality and continue to discuss rationality on the assumption that we are talking about the epistemic kind. There is a lot of skepticism these days about the possibility that rationality can be interest-neutral. Perhaps most influential here has been Michel Foucault, who argued that truth and power were intimately linked. To get the full sense of what this means, ‘truth’ needs to be put in inverted commas, as Foucault himself did when trying to sum up the basic proposition he was putting forward: ‘“truth” is linked in a circular relation with systems of power which produce and sustain it, and to effects of powers which it induces and which extend it.’ On this understanding, ‘truth’ cannot be detached from relations of power and so has no neutral meaning: ‘It’s not a matter of emancipating truth from every system of power (which would be a chimera, for truth is already power), but of detaching the power of truth from the forms of hegemony, social, economic, and cultural, within which it operates at the present time.’8

There is surely an important insight here that Foucault is trying to grasp. It is certainly true that whenever we see people claiming to present disinterested knowledge we should ask whether this is not in fact ideology disguised as empiricism, value in the guise of fact. The state will use the claim that something is scientific, for example, as a justification for a policy that suits its ideology. But it does not follow that whenever you see something claimed to be knowledge, you will always find someone using that knowledge claim as a means of exerting power. The idea that claims to disinterested fact are often no such thing is not the same as the claim that there is no such thing as a disinterested fact. Whenever thinkers have tried to go this far, they have always ended up in absurdity. Luce Irigaray, for instance, notoriously suggested that perhaps even E = mc2 is a ‘sexed equation’, expressing masculine dominance. Why? Because ‘it privileges the speed of light over other speeds that are vitally necessary to us’.9 But the fact is that scientists, East and West, male and female, all have equally good reasons to accept the equation. This is interest-neutral science, pure and simple. As the physicists Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont put with almost comical plainness, ‘Whatever one may think about “the other speeds that are vitally necessary to us”, the fact remains that the relationship E = mc2 between energy (E) and mass (M) is experimentally verified to a high degree of precision, and it would obviously not be valid if the speed of light (c) were replaced by another speed’.10

A common retort to this is to say that the practice of science is never value-neutral, because at the very least there will be decisions about what to focus research on – whether to spend money flying people to Mars or curing breast cancer. But this claim that there is no such thing as the value-free practice of science is an importantly different claim to the one that there are no value-free scientific truths. A scientist may well be led by ideology to investigate the harmful effects of pesticides on human health, but if she is a good scientist, and if her findings are corroborated by others, the truths she discovers can still be value-free.

Tim Lewens provides a very clear example of this. He argues that Marx and Engels were correct when they claimed that Darwin’s thought was ‘steeped in the industrial capitalist milieu’ that surrounded him. But that did not invalidate his conclusions. ‘What matters is not, in this case, whether Darwin’s views are influenced by his bourgeois ideology, but whether that ideology acts to distort, or to reveal, the workings of the natural world.’11

The key distinctions here are very simple but so often overlooked. The following four statements are equally true and entirely compatible.

Many value-laden beliefs are presented as disinterested truths for purposes of ideology and power.

Disinterested knowledge is often used to promote value-laden ends.

The practice of science is value-laden.

Rational argument requires the giving of reasons which are interest-neutral.

To deny that interest-neutral reasons for belief exist ends up in either absurdity or emptiness. It is absurd if it means that, for example, there is no fact of the matter about how far one point on a map is from another. It is empty if it simply means that every time we assert a fact, we must also be asserting some kind of value, such that we desire the truth, or that we think it is important to know the distance between two points on a map. Of course values and interests infuse how we live and how we think. But that does not mean values and interests permeate the content of every knowledge claim.

(v) Compulsion

It is, however, more than possible to have a weak argument that offers assessable, comprehensible, defeasible and interest-neutral reasons for believing X. For the argument to have objective force it must in some way be compelling. Turned over and examined on all sides, any rational agent who understands the argument should find herself feeling forced – or at least strongly pushed – to accept the conclusion, whether she likes it or not. Furthermore, this compulsion should be a consequence only of the kind of features of the argument already set out: i.e. the assessable, comprehensible and interest-neutral ones. If something else, such as personal incredulity or wishful thinking, makes someone feel compelled to believe something, then this is not the kind of compulsion which is to be sought in a rational argument.

This idea is captured in the notion that a strong argument carries objective weight. In using the term ‘objective’ here, we are reporting the sense that the force of the argument comes from somewhere outside ourselves. And the metaphor of ‘weight’ captures the sense we have that something other is placing a burden on us to accept it.

This is plain enough, and evident in any example of a good objective argument. When you understand that 1 + 1 = 2, for example, you realise that you can’t but accept it as true. When you accept the evidence that, say, smoking is a major cause of lung cancer, you feel that you must accept the argument, not that you are choosing to do so of your own free will.

It is, however, very difficult to explain just what makes an argument compelling in this sense. Any explanation is likely to be somewhat circular, although, as I have argued before, this needn’t be vicious. In this case, we can see that the idea of compulsion is a necessary corollary of the other features of rational argument. If you can see that an argument is assessable by all, and that assessment has not raised any major problems with it; if you also understand it; and if you can see that it does not require you to share any particular agent’s interests to accept it: such an argument must carry with it a certain degree of force.

There is a sense here in which there is simply nothing left for a rational agent to say to someone who claims to have followed all these steps but is still not convinced. Take the smoking example. Imagine someone saying, ‘Yes, I can see the evidence. I clearly understand it. I know how to assess it and I see nothing wrong with it. I can also see that the case does not require you to have any kind of personal interest in the destruction of the tobacco industry. But I’m not convinced.’ In such a case you would be justified in concluding that the person was just not being rational. Whatever was stopping the person from feeling the force of the argument, it wasn’t reason. The fact that there is nothing left to say to such a person could be seen as dispiriting, but it is not realistic to suppose that we can always make a case for reason or a reasoned case that everyone is bound to accept. If someone is not rational, no rational argument that they ought to be is going to work. It’s like trying to convince someone with no taste buds that something is delicious by getting them to taste it.

To understand the particular character of what we might call this ‘rational force’, it is worth distinguishing it from ‘psychological force’. In one sense, rational force is of course psychological: it is something we experience in the mind. But there is a specific sense of psychological force which is a little different. This is the sense in which we find ourselves strongly inclined to believe something and to act accordingly. This is often in spite of or even contrary to what we can also see has rational force.

The smoking example is again helpful here. The person I have described simply doesn’t feel the rational force of the argument that smoking causes lung cancer. More common, however, is the person for whom the rational force just doesn’t translate into psychological force. Such a person understands fully that smoking is very bad for her health and that she ought to give up, but for any number of reasons, although she sees that the rational argument for giving up is compelling, it does not move her to do anything about it. The compulsion remains purely rational and does not have any psychological effect, in this particular sense of the term.

This kind of distinction seems to be extremely common when it comes to moral philosophy. I know many people who claim that they find the rational argument for ethical vegetarianism unanswerable, but they still don’t feel inclined to give up meat. Similarly, many are persuaded by utilitarian arguments of the kind offered by Peter Singer, arguing that we ought to give up almost all our wealth, and yet rational conviction does not translate into psychological motivation.

These examples are clear enough, I think, to point us towards the phenomenological character of the kind of rational compulsion I am describing here. It is a very specific sense that an argument is unanswerable, or that a reason has no defeating counter-reason, a sense which is independent of any desire or inclination we might have to use the argument or reason as the basis of action. To be rational entails having the ability to recognise that a rational argument has conclusions that are in some sense demanded by it, not merely invited.

3. The boundaries of the rational

As a way of both testing and illustrating how this account of the objectivity of rationality works, it is worth looking at two examples of forms of understanding that stand at best on the fringes and at worst outside the domain of the rational: anecdotal evidence and mysticism.

To say that the evidence for something is ‘merely anecdotal’ is to dismiss it as inadequate. For that reason, few explicitly claim to base their beliefs on anecdotal evidence. In practice, however, that is exactly what many people do. This is perhaps clearest in the case of homeopathy. There has been much research into the efficacy of homeopathy and the overwhelming scientific consensus is that it just doesn’t work. And yet, as I am soon reminded whenever I write or talk about this topic, many otherwise sensible, intelligent people remain convinced that it does. None believe that their convictions rest on blind faith. All offer reasons for belief, and in so doing they purport to place their claims in the domain of the rational.

These reasons tend to be of three sorts. First, there are those of personal experience. ‘I have seen how much people have benefited by the care and expertise of homeopathic doctors’ is a typical testimony. Second, there are claims of impressive historical successes. Pre-eminent in the lore of homeopathy is the Soho cholera epidemic of 1854, where victims who were admitted to the London Homoeopathic Hospital had a mortality rate of 16%, compared to 53% for those who ended up at the Middlesex Hospital. Finally, they will cite selected studies.

We can see why these reasons deserve to be considered as attempts to provide a rational case for the efficacy of homeopathy. They appear to be comprehensible and assessable, and in turn defeasible. Those who offer them also see them as interest-neutral and compelling. We should reject them, however, because when we examine these supposed characteristics more carefully, they are not present to a sufficient degree.

Assessability is the key here. Claims are made which appear to be assessable, but when they are indeed properly assessed, they fail the test. Obviously, a claim such as ‘I have seen how much people have benefited by the care and expertise of homeopathic doctors’ is not in itself assessable as it is a first-person report. It becomes assessable if it is supplemented by the likes of ‘and you too could see this for yourself if you bothered to look’, which is the usual follow-up. But of course one cannot know anything about the efficacy of a medical treatment merely by first-person observations. You need proper trials which compare outcomes using different treatments. So the claim to have ‘seen for myself’ turns out either to be unassessable after all, or merely a pointer towards proper research.

The appeal to historical examples is flawed in the same way. The statistics concerning the two hospitals in 1854 may well be correct, but we cannot know whether this provides any good reason to believe homeopathic treatments were the cause of the difference unless we know the full circumstances. In this case, it has been suggested by Ben Goldacre that the homeopathic hospital probably did better because it simply did no harm, while the interventions such as bloodletting practised elsewhere only made matters worse.12 This may or may not be correct, but the mere presentation of the different death rates by itself does not provide properly assessable data.

So we are left with studies, and these overwhelmingly show homeopathy to be no better than placebos. If you look at the evidence against the efficacy of homeopathy, it is rationally compelling. Those who argue otherwise look guilty of approaching the evidence in a non-interest-neutral way, selecting those studies which are favourable and rejecting those that are not. Their reluctance to back down when other reasons are shown to be lacking also suggests, although it does not prove, that they do not see their reasons as genuinely defeasible at all.

This explanation for why we should not accept the purported reasons in favour of homeopathy’s efficacy shows how the account of rationality I have offered provides a framework for distinguishing what we should rationally accept and reject. But crucially, it also shows why it is often unhelpful and inaccurate to accuse opposing parties in an argument of irrationality. The homeopathic community tries to make rational arguments but fails. It does not argue in a way which is inherently irrational, it simply fails to provide arguments that are compelling when assessed in an interest-neutral way. We should distinguish between arguments in two ways. To say they are rational or irrational is to describe their mode; to say they are good or bad is to distinguish them by their quality.

A second kind of argument is one based on what we can broadly call mystical experience. To give a simple example, there are those who claim to have achieved some form of knowledge by the use of LSD that the self is not real. Others claim to have seen the world ‘as it really is’. I think such arguments are inherently non-rational. They are interest-neutral, in that there seems no reason to think that they are motivated by prior commitments or self-interest. They might seem to be assessable because anyone can take LSD and see for him- or herself whether this is true. But they are not properly assessable because they are not properly comprehensible. The nature of such experiences is that they cannot be adequately described: you have to ‘be there’. So even the terms used to describe the claims made are taken to be imperfect proxies for a more direct kind of knowledge or insight. This makes them profoundly non-objective. An alien with a different brain chemistry, for example, would not be able to access the same state or thereby assess it.

Nor do such claims appear to be properly defeasible, in that people who have the experiences swear that they have seen the truth and are not open to being persuaded otherwise by rational argument, which they think fails to capture the experience. Finally, the reasons they offer for their conclusions are compelling only in the psychological sense. They are not rationally compelling because no rational reasons are given for them.

That does not mean that we can therefore conclude that mystical experiences provide no reasons for belief. The conclusion is the more modest one that they provide no rational reasons for belief. It remains an open question whether there are any good non-rational reasons for belief we should accept. But if there are, the case needs to be made.

4. Rational catholicism

I have argued that judgement is required at every level to construct or analyse a rational argument. But to say judgement is required is not a vague way of saying that everything is up for grabs or down to personal inclination. A rational argument must meet certain standards of objectivity. These standards ensure that judgement does not have free rein but plays a very specific role, providing a way to distinguish between arguments that are non-rational, such as those that are based on mystical experience, and those which are rational in form but fail to meet the standards of a good rational argument, such as those for the efficacy of homeopathy.

This account of rationality also explains why it is natural to see logical arguments as the paradigms of rationality. When an argument is set out in explicit logical steps it becomes clearly comprehensible and assessable, which also ensures it is defeasible. And if the premises are correct, that gives an interest-neutral reason to accept the force of the conclusion. But the fact that formal deductive arguments most clearly pass the test for rationality does not mean that no other form of argument does. Deduction does not define rationality, it merely exemplifies its virtues more clearly than is usually possible.

This view of rationality has important consequences for our conception of what reason is. It shows how it is possible to abandon the idea that we can arrive at the truth by appeal to objective facts and logic alone, without necessarily embracing total relativism, since the strong constraints on the requirements for objective rational arguments severely limit the range of possible rational accounts we can give of the world. It suggests that good judgement is much more than just opinion, and something less than the mere following of logical rules.

This conception of rationality might help us to explain some otherwise puzzling features of rational discourse in general, and philosophy in particular. In general terms, we might call this the catholicism of rational discourse. In every department of a typical university, we see rational inquiry. And yet the methods and assumptions of the different disciplines vary enormously. Sometimes, these differences can appear to mark fundamental disagreement about the nature of rationality. Some belligerent scientists, for instance, insist that anything being done in the arts and humanities which is not based on the empirical methods of science is just nonsense.

I think that, on the whole, these divisions are at least in part a product not of a different conception of rationality but of different judgements about what kinds of reasons satisfy the requirements of rationality. So, for instance, a lot of natural scientists think that only empirical scientific data are clear, assessable and interest-neutral enough to provide the basis for a compelling argument. Others would say that there are important questions which cannot be settled by scientific means, and that we ought to look for the strongest reasons to determine the answers to these that we can find. Such disagreements are inevitable, since what counts as an objective reason for belief in the end depends in part on judgement.

Similar divisions are found within disciplines, such as philosophy. Take that between those who see philosophy as being continuous with natural science and those who do not. Here again, the distinction can be seen to cut across a common conception of rationality. Put simply, the former are much more impressed by natural science than the latter and therefore believe that our most objective reasons for belief are grounded in natural science. If this is so, then there may often be no deep disagreement between the two camps about the nature of philosophy. This might also help account for why philosophers in both the ‘analytic’ and ‘Continental’ schools are basically doing philosophy but why, nonetheless, they sometimes appear to be doing quite different things. So it is not that there are different fundamental conceptions of rationality at work, it is rather that each tradition places emphasis on different elements of the rational toolkit.

Accepting the catholicism of rational discourse also means keeping our positions on substantive issues in philosophy separate from our position on the nature of reason, broadly construed. That is why my account has not tried to give any substantive account of what it ultimately means for anything to be true. In particular, when talking about objectivity I did not talk about the way things are independently of how we view them, as that would commit me to a kind of metaphysical realism. Nor do I describe true statements as those which correctly describe the world. My account of rationality solely concerns the process of reasoning. To be truly catholic it has to be thus constrained, or else it could not claim to describe the way in which even people with wildly different substantive views reason.

There is another odd feature of philosophy that I think my account helps to explain. That is how it is both the most rigorous discipline in its employment of arguments and yet one of the most indeterminate in respect of its findings. Consensus is omni-absent in philosophy yet the arguments of philosophers are among the most rationally rigorous in the humanities or the sciences.

I think my account helps makes sense of this because it shows how rationality is highly rigorous both in its demand for objective reasons for belief and in the way deductive logic is one of its most powerful tools. But unlike data in the natural sciences, the raw data of philosophy is not quantifiable data from empirical experiment. It is rather the whole of human experience. Philosophy also lacks the settled, agreed methods of a science that enable consensus. Philosophy, then, relies entirely on rationality and nothing but. This involves a high degree of commitment to the rigours of argument but also, ultimately, an acceptance that rational argument does not lead linearly to only one answer, since you cannot take judgement away from rationality. Our reliance on rationality as our sole resource makes us both rigorous thinkers and condemned ultimately to use our own best judgement.

Understanding how it is that philosophy demands the rigour of rational argument, but that rational argument itself demands the use of judgement, therefore helps us understand why it is that philosophy pushes us so hard intellectually yet cannot compel equally intelligent thinkers to agree. As I suggested at the beginning of this chapter, reason is the kind of guide that helps us find our way, but does not prescribe a single path. Reason is something we use, and while we cannot take it just anywhere without doing violence to it, nor does it simply carry us forward, like a self-driving car.13

5. Ending the truth wars

Freud once said, ‘intolerance finds stronger expression, strange to say, in regard to small differences than to fundamental ones’.14 The same point was made, perhaps better, in Monty Python’s Life of Brian, in which the People’s Front of Judea spat blood at the mention of the Judean People’s Front and the Judean Popular People’s Front.

The problem is that if you look at anything very closely, including ideas and ideals, differences which appear small from the wider perspective suddenly appear very large indeed. And so it should be. It is precisely our ability to examine the objects of intellectual endeavour closely and discern differences invisible to the naked mind’s eye which allows us to deepen and extend our learning in the humanities and the sciences.

However, if we never step back and examine the broader picture, we can become blinded to some important features of intellectual life that should be obvious to us. And while intellectual hyperopia gets in the way of first-class, specialised academic work, intellectual myopia is, I would argue, a more pernicious and widespread affliction of intellectual life today.

I have argued that this myopia blinds us to the shared sense in which almost all of us are committed to reason. This affliction has increased the intensity of what Simon Blackburn has called ‘The Truth Wars’ in his book of the same name. The general history of this conflict has been chronicled many times. First came the Enlightenment, and the championing of reason, truth and science over authority, falsehood and superstition. Then, in the twentieth century, many lost faith with the Enlightenment project. Some, such as Adorno and Horkheimer, went so far as to suggest that Auschwitz was the logical conclusion of the Enlightenment. ‘Enlightenment is totalitarian,’ they argued, and the ‘unconditional realism of civilized humanity’ it engendered ‘culminates in fascism’.15

Reason has been one victim of this backlash, but arguably truth has suffered even more. The result is now a stand-off between what Bernard Williams called the ‘deniers’ – those who deny that there is such a thing as ‘the truth’ that reason aims at – and the ‘party of common sense’, those who claim that the truth really is out there. Williams wrote that ‘the deniers and the party of common sense, with their respective styles of philosophy, pass each other by’. This diagnosis is correct. The gulf of mutual comprehension is greater than that of any fundamental difference. What we have here is a case of both sides getting very worked up about what are, in the grand scheme of things, small differences. And as with the freedom of Judea, so here the tragedy is that a greater cause, one that both sides support, is suffering as a consequence of internal divisions. That greater cause is a commitment to reason, no matter what reservations some may have about the history, use and connotations of that term. Despite their apparent differences, it should be obvious that both ‘deniers’ and the ‘party of common sense’ share something like the thin conception of reason and rationality that I have been defending.

I think the disagreements over the nature of truth can also be seen as relatively minor. Take as an example where Williams disagrees with his old sparring partner Richard Rorty. Their official disagreement is that Williams thinks there is a thing called the truth, and Rorty doesn’t. The real disagreement, however, is essentially that Williams thinks that it matters whether or not there is a thing called the truth, whereas Rorty doesn’t. Williams thinks it is inconsistent and dangerous to deny that there is a truth; Rorty thinks it pointless and immature to insist that there is. Both Williams and Rorty are committed to what Williams calls the two virtues of truth: sincerity and accuracy. However, Williams thinks that Rorty is just wrong if he thinks he can be committed to the virtues if he is not also committed to the idea of truth.

There are, of course, major disagreements here. And if you are serious about intellectual work, they matter. But it is worth remembering that there is a great deal agreed before the disagreement arises. Being committed to the virtues of sincerity and accuracy is no small matter. For though what that entails in terms of commitment to the truth is highly contentious, what it means with regard to commitment to rationality is, I would argue, much less controversial.

Similarly, although both sides of the debate probably disagree in their thick conceptions of rationality, they will agree on the thin one. You just cannot have a sincere intellectual debate unless you in some sense attempt to provide what I have called objective reasons for belief, even if you refuse to use the word ‘objective’.

The debate about whether there is such a thing as the truth is therefore largely a bogus one. Deniers of truth are as quick as anyone else to call out liars, especially in politics, or to feel aggrieved at being libelled or misrepresented. Critics mock them for this, claiming that it shows their denials are insincere. That is a mistake. Their denials are not insincere but technical. And the fact that these technicalities might matter some of the time doesn’t mean they matter in most ordinary cases. We ought to recognise the ‘truth wars’ for what they are: a dispute over details.

In our disagreements we sometimes forget that, as a community of rational inquirers, we share many core values. Perhaps we don’t like the connotations terms like ‘reason’ and ‘rationality’ have, thinking that they suggest a false objectivity or authority. But it is only within the domain of rational inquiry that we can sensibly express these concerns. Those who urge us to reject the idea of truth, for example, do so by offering comprehensible, assessable, defeasible reasons for doing so, reasons that aim to speak to people regardless of their own interests and which have some force.

Think of any serious participant in intellectual life. Is there any who does not try to be as comprehensible as is possible? Many are so incomprehensible that we doubt them, but this is almost always a failure of execution, not a success born of intent. Does anyone assert that it is not possible for anyone else to assess the merits of their claims? Very few, and the whole raison d’être of publishing and discussion is precisely that others are, in principle, capable of assessing what they have read or heard and sharing these assessments. Does anyone declare that what they have to say is wholly relative to the interests only of a particular sector of society? Surely not. Even as we acknowledge our biases and partial perspectives, we strive to overcome them as much as is possible. Does anyone think there is no way they could possibly be wrong about what they believe? We may sometimes feel this, but the fact that we nonetheless leave ourselves open to criticism and take those criticisms seriously shows we are committed to the idea that rational inquiry demands we treat our beliefs as defeasible. And finally, when you have seen someone provide what seem to you good reasons for their accepting their position, is your agreement not in some sense involuntary? Similarly, can you not help but dismiss arguments that seem to you weak or ill-founded?

As convinced as I am of the essential truth of my account, I am aware that there will be many objections. Every one of my five characteristics of the thin notion of rationality can be understood in many ways, and even rejected. But I would maintain that this unease is not a symptom of any inherent flaw in my account. Rather, any intelligent, reflective reader is going to be concerned with how to thicken such conceptions, and also to challenge them. But unless I and my readers shared some thin conception of what rational debate looks like we could not come together to discuss them in the first place.