Bees and wasps all belong to the large order of insects that is known as the Hymenoptera. There is, however, one big difference in the behaviour of the two groups: bees all feed their youngsters with pollen and nectar, whereas wasps rear their grubs on a diet of meat, usually insects or spiders.

Asked to name some bees, most people are likely to come up with just two: the honey bee and the bumble bee. Gardeners may add the leaf-cutter bee, but there are actually over 250 different kinds of bees in the British Isles. The adults feed primarily on nectar and, although by no means all of them are likely to occur in your garden, they all play a major role in pollinating our wild and cultivated flowers, including fruit crops (see).

On each expedition from its hive, a honey bee tends to visit just one kind of flower, so pollen is not wasted on flowers where it cannot effect pollination. This makes honey bees particularly good pollinators. Fruit growers often borrow beehives when their trees are in flower to guarantee successful pollination of the blossom and a good fruit crop – and the bee keepers benefit from a good yield of honey, which the bees make from the nectar.

Michael Chinery

The small flowers of Photinia davidii (see here) literally ooze with nectar, which is being sampled here by a honey bee. There are several races of honey bees, each differing slightly in colour but all usually with conspicuous pale bands on their abdomen.

The bees are incredibly efficient at collecting nectar because an individual finding a good source tells the rest of the colony about it by ‘dancing’ when it returns to the hive. The direction and speed of the dance tells other workers exactly where to find the nectar, and they fly out to gather it.

You can get a reasonably good idea of the efficiency of this recruitment by putting a spoonful of honey or strong sugar solution on a saucer and persuading a bee to drink from it. This is not as difficult as you might think: if you dip a small twig in some honey and hold it close to a bee on a flower, the bee will readily transfer its attention to the honey and you can carry it to the saucer. Mark the bee with a small spot of non-toxic paint while it is feeding and then watch it fly off. As long as its hive is not too far away, you may well find it back with a gang of friends in a few minutes.

Bumble bees are generally bigger and furrier than honey bees. There are 25 British species, although some are very rare and only half a dozen are likely to occur in the garden. They usually nest in the ground, often in hedge-banks, and their colonies rarely contain more than a few hundred individuals, whereas a honey bee colony may contain over 50,000 insects. Bumble bees also differ from honey bees in that their colonies last for just a few months. Only the mated females (queens) survive the winter and they start new colonies in the spring. Bumble bees make no combs and do not store much honey, but they are still important pollinators.

FLOWERS FOR BEES

Try growing some of the following flowers to encourage bees into your garden:

• Borage

• Foxglove

• Globe thistle

• Helichrysum (everlasting straw flower)

• Knapweed

• Lungwort

• Marjoram

• Poppies (especially the opium poppy)

• Red clover

• Red deadnettle (various cultivars)

• Sage

• Teasel

Michael Chinery

Copious supplies of both nectar and pollen mean that the little hover-fly on the right can feed happily alongside the much larger bumble bee on this colourful helichrysum flower.

Michael Chinery

Guided by the dark spots, a bumble bee makes its way right inside a foxglove flower to sample the rich supply of nectar at the top of the bell. While feeding, the bee will be liberally dusted with pollen, much of which will be carried home in the pollen baskets on its back legs.

Michael Chinery

The wool carder bee nests in holes in wood. She gathers and combs plant hairs with her toothed jaws and mixes them with saliva to line her nest and make the cells for her eggs.

Many bumble bee species have become noticeably rarer in recent years. The loss of our flower-rich meadows and roadside verges may have contributed to the decline, together with the loss of many miles of hedgerow nesting habitats. You can help to restore the fortunes of the bees by planting nectar-rich flowers and providing artificial homes (see here).

The majority of bees are solitary insects, with each female working alone to make a small nest. Each nest consists of a few cells and may be excavated in the ground, in dead wood or in hollow stems and other crevices. Leaf-cutter bees are well known to gardeners because they make their nests with sections of leaves cut from roses and other plants.

Other solitary bees make their nest cells with sand or mud, with fibres plucked from plants, or with the sawdust created while excavating in wood. The cells are stocked with a mixture of pollen and nectar and an egg is laid in each one. The female then seals the cells and flies away. She has no contact with her offspring. It is easy to encourage these useful and interesting insects to settle in your garden by providing them with suitable nest sites (see pages).

SAFETY TIP

Solitary bees and wasps rarely sting us, and even the social ones are not usually very aggressive as long as you don’t stand in front of their nests. Their stings can be painful, but the pain is usually short-lived. If you are stung by a honey bee the strongly-barbed sting will stay in your skin. Don’t try to pull it out with tweezers, as this will just force more poison into you. Scraping it out is a much better way to deal with it.

Michael Chinery

Few people have a good word to say for wasps, and many immediately reach for the insecticide or a rolled-up newspaper when one appears, which is a pity because they really do a lot of good in the garden!

The most familiar of the 180 or so British wasps are the social species, several of which nest in and around our homes and often cause consternation or even panic around the tea table in the autumn. These black and yellow insects build ball-shaped nests with paper, which they make themselves from wood pulp. In spring and summer you can often see, and even hear, wasps scraping wood from sheds and fence posts. Mixed with saliva, the wood is moulded into tiny strips, thousands of which are joined together to form the nest. A completed nest consists of several tiers of hexagonal cells enclosed by a number of insulating sheets. Some species hang their nests in trees and shrubs, while others build in hedge banks or in roof spaces and other cavities in buildings.

Thousands of grubs are reared in the cells and the inhabitants of a single nest munch through something like 250,000 insects during the summer. Many of these are harmful caterpillars and flies – a point worth remembering when you are tempted to reach for the aerosol. Like the bumble bee colonies, our wasp colonies are annual affairs, with only mated females surviving the winter.

Michael Chinery

Wasp colonies break up in the autumn when they have finished rearing their young and, with no more work to do, the insects turn their full attention to our fruit and other sweet things – a just reward perhaps for their earlier pest-controlling activities.

Michael Chinery

This queen wasp is using her strong jaws to gather wood fragments, which she will turn into strips of paper.

Less than half of our British wasps sport the black and yellow coloration that most people associate with wasps. Many are jet black. The great majority are solitary creatures, nesting in burrows and crevices in much the same way as the solitary bees but stocking their nests with paralyzed insects or spiders. Some specialize in aphids or small caterpillars, and are therefore friends of the gardener, whereas others stick to various flies.

Solitary wasps can be encouraged into the garden in the same way as the solitary bees. Few people will want to encourage the social wasps to nest in their garden, but as long as they do not settle too close to the house or other regularly-used areas there is no need to destroy them.

Michael Chinery

Many harmless insects, including hover-flies (top) and clearwing moths (above), mimic wasps to good effect. Birds and other predators that have learned that wasps are unpleasant leave the similarly-coloured mimics alone as well.

The solitary bees are excellent pollinators of our garden plants – especially in the spring, when they can be seen foraging on fruit trees and bushes. The tawny mining bee is one of many species that nest in the ground, and its little volcano-shaped mounds can often be seen on the lawn in the spring. Others tunnel into wood and even into soft mortar, so don’t be in too much of a hurry to re-point old garden walls; the bees will not do much harm as long as not too many of them choose the same patch of wall.

Although most bees are prepared to do some digging when preparing their nests, they are generally happy to accept ready-made tunnels. The harebell carpenter bee, which feeds almost exclusively on pollen and nectar from campanulas, is small enough to be able to use old woodworm holes in sheds and fences.

You can attract this and many other solitary bees by constructing a ‘bee hotel’. This consists of one or more planks of wood, 10–15cm (4–6in) thick, drilled with numerous holes ranging from 2–10mm (1/12–2/5in) in diameter. Fix the planks to a wall or a fence in a sheltered, south-facing position and then watch the bees select their ‘rooms’ and stock them ready for egg-laying. A large log or a tree stump drilled with holes is equally acceptable to the bees. With about a quarter of Britain’s native bees now listed as endangered species, anything that you can do to help them must be a good thing.

Solitary wasps will also use the ‘hotel’, and watching them will reveal that each species stocks its nest with a particular kind of prey – mostly aphids, caterpillars or flies, although some wasps prefer to hunt spiders.

WILDLIFE PROJECT – A FLOWER POT NEST

Rolando Ugolini

Michael Chinery

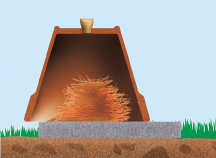

A flower pot with a diameter of about 15cm (6in) makes an acceptable bumble bee home. Part-fill it with old mouse bedding and bury it on its side in a bank of soil. Ensure that the drain hole is visible and a queen bumble bee might well take up residence. Alternatively, invert the flower pot on a small paving slab, overlapping the edge so that there is a small gap for the bees to get in. Plug the drain hole to keep the rain out.

CJ Wild bird Foods/David White

Hollow canes or other tubes up to a centimetre in diameter make great homes for solitary bees. Pack them into a tin or a length of drain pipe 15cm (6in) long. Make sure that the bees can enter only at one end; if you use a length of drain pipe, you will have to block up the ends of the tubes with modelling wax.

Bumble bees usually nest on or under the ground, often in old mouse nests in well-drained banks. They sometimes accept artificial homes, and a simple wooden box with a couple of 15mm (⅔ in) holes in the sides makes a good bumble bee home. Stuff it with old mouse or gerbil bedding – scrounged from the pet shop if you have no pets of your own – and bury it in a pile of leaf litter at the base of a hedge so that the holes are just visible. Do this in early spring, when the queens are searching for nest sites. If it is accepted, you will be able to watch the coming and going of the bees throughout the summer. A medium-sized flower pot, buried in a bank with the drain hole just visible, may also be acceptable to bees.

CJ Wild bird Foods/David White

Dozens of solitary bees, of several different species, may take up residence in a simple ‘bee hotel’, made from a thick plank screwed to the wall.

Although bumble bees are particularly attracted to deep-throated blue and purple flowers, such as foxgloves and sage, they feed at a wide range of flowers. Lungwort is a good source of food early in the spring, but for attracting and feeding the insects later in the spring you can’t beat Photinia davidii, also known as Stranvaesia davidii (see here). The small creamy flowers of this evergreen shrub attract so many worker bees with their slightly sickly scent in May that a bush in full flower can be ‘heard’ from several metres away. Your garden birds will also enjoy the red berries later in the year.