In the spring of 1959, Saint Phalle, her husband, and their two children went on a weeklong vacation with the painter Joan Mitchell and her companion, Jean-Paul Riopelle (see here). The two couples had become friends in Paris, where they were all living and working. Saint Phalle, then twenty-eight, was painting while taking care of her children; her husband, Harry Mathews, was a writer working on his first novel; and Mitchell and Riopelle were well-established artists. One night at dinner during their vacation, Mitchell turned to Saint Phalle and said, “So you’re one of those writer’s wives that paint.” The remark, Saint Phalle wrote years later, “hurt me to the quick. It hit me as though an arrow pierced a sensitive part of my soul.”

Returning to Paris, Saint Phalle decided that if she wanted to be taken seriously as an artist, she would have to make a more drastic commitment. Since marrying Mathews at eighteen, she had worked as a model, attended drama school, suffered a nervous breakdown, and discovered a talent and passion for art. But she had never had the opportunity to give all her energy and attention to one thing. In 1960, still smarting from Mitchell’s comment, she left her husband and two children, ages nine and five, so that she could “live her artistic adventure to the full without the perfect balance that I found between my work, Harry and the children.” She intended to remain single but soon began a relationship with the Swiss artist Jean Tinguely that would last until his death in 1991. Her real commitment, however, was to her work. “My secret jealous lover (my work) is always there and waits for me,” she wrote.

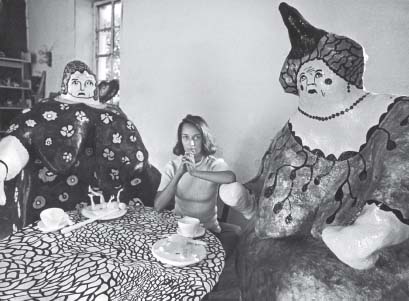

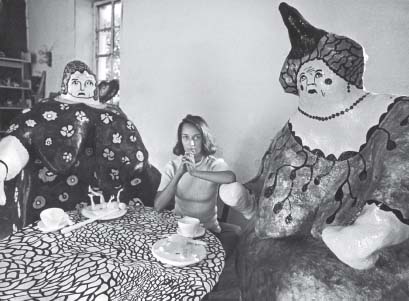

Niki de Saint Phalle with some of her sculptures, circa 1971

He is tall, elegant, and like Count Dracula wears a black cloak. He whispers in my ear that I don’t have much time left for what I have to do. He is jealous of every moment I don’t spend with him. He is even jealous of my closed bedroom door. Sometimes he flies through the open window of my room at night, in the shape of a giant bat. I tremble when he embraces me with his wings. For a moment I defend myself in my long white nightshirt. His teeth sink into my soul. I am his.

Only a couple years into her artistic adventure, Saint Phalle became famous for her “shooting paintings,” made by attaching bags or cans of paint to assemblages and shooting them with a rifle, a pistol, or a miniature cannon, splattering paint over the artwork. A few years later, Saint Phalle began working primarily as a sculptor, and in 1978 she embarked on the Tarot Garden, a monumental sculpture garden that she built in Tuscany over the course of twenty years. After the site’s largest sculpture, a house-size female figure, was completed, Saint Phalle moved into its interior, turning one breast into her bedroom and the other into her kitchen. (The only two windows were built into the sculpture’s nipples.) “I enjoyed living the life of a monk, but it wasn’t always pleasant,” she later wrote of her seven years living inside the sculpture. “There was a large hole in the ground where I kept my provisions, and I cooked on a tiny camping stove. Every hot night I woke up to find swarms of insects from the marshes buzzing round me, as in a childish nightmare.”

Wealthy friends had provided the land for the Tarot Garden, but financing the construction over so many years was a constant struggle, and the artist resorted to a variety of means (including selling her own perfume, called Niki de Saint Phalle). But she also relied on scores of unpaid helpers, whom she lured onto the project through her immense personal charisma. She was aware of the effect she had on others, and used it to her advantage. “Enthusiasm is a virus and a virus that I am able to propagate very easily because enthusiasm enables me to do anything I want, no matter how difficult it is,” she wrote. Whether the work was in the best interest of her friends and collaborators was not her concern. “People are very important,” Saint Phalle wrote. “They are essential but they are not the most important. The most important remains the work, the total obsession, the virus.”

Asawa was a Japanese American artist who learned to draw in an internment camp during World War II and pioneered a unique style of looped-wire sculpture in the 1940s, while attending Black Mountain College in North Carolina. There she studied with Anni and Josef Albers and Buckminster Fuller, befriended Merce Cunningham and Robert Rauschenberg, and met her future husband, Albert Lanier. In 1949 she joined Lanier in San Francisco, where he was working as an architect and where Asawa continued her sculpture experiments while raising an eventual six children, born between 1950 and 1959. Asawa came from a large family herself—she was the fourth of seven children born to Japanese immigrant farmers in California—and she never saw children as an impediment to her artwork; rather, she felt that art should be a part of daily life, and she made her sculptures with the kids around her, whenever she could squeeze it in between other chores. “My materials were simple,” she said, “and whenever there was a free moment, I would sit down and do some work. Sculpture is like farming. If you just keep at it, you can get quite a lot done.”

The Brooklyn-born sculptor began her career as a painter but, around 1960, moved into three-dimensional work, creating immersive environments from plastic, water, and fluorescent lights, and later building monumental sculptures in Cor-Ten steel. Katzen knew that she wanted to be an artist from a young age—“I was going to be an artist even when I was in kindergarten,” she said—and over the years she became adept at carving out time for her work despite all manner of obstacles. After high school, Katzen couldn’t afford to attend art school full-time, so she lived at home with her mother and stepfather, worked during the day, and took night classes. Because her stepfather was “adamant about my not working at home,” Katzen recalled later, she would do so only after he went to bed, setting up her work and painting until 2:00 or 3:00 a.m., then putting everything away and airing out the room before going to sleep.

Katzen married at nineteen, and after college moved with her husband to Baltimore. As she began to establish herself as an artist she was also the mother and chief caretaker of two small children. At the time, Katzen used the upstairs of her house as her studio, and she worked when her kids napped or after they went to bed at night. In the 1970s, the art historian Cindy Nemser asked her how she managed it all. “I worked from eight in the evening to two in the morning,” Katzen said.

I also set up a schedule of work knowing that I wanted to put in a forty-hour week. I felt that I had to do that. In the beginning it was very hard and I used to chalk out the hours that I got out of the week. This week I only got four hours. Well that is very bad. This week I got eight hours. That is better, but it is nothing. And I made up my mind that even if I didn’t do anything, even if I just sat there or if the things were messes or if I destroyed things (and I went through real rituals of making nothing and destroying lots of stuff that I had made), regardless of anything, that time was going to be spent in the studio. That is the way I did it. . . . When they napped, I would nap too or I would go upstairs and work.

If Katzen was working and her kids woke up and needed something to do, the artist would yell, “Here are some crayons and paper,” and throw them down the stairs.

“A really good picture looks as if it’s happened at once,” the Abstract Expressionist painter said. “It’s an immediate image . . . it looks as if it were born in a minute.” Of course, Frankenthaler might have abandoned ten versions of a painting before she arrived at the one that felt spontaneous and true. And getting to that image required more than just practice or experimentation, she thought—it came from a marshaling of all the painter’s resources. “One prepares, bringing all one’s weight and gracefulness and knowledge to bear: spiritually, emotionally, intellectually, physically,” Frankenthaler said. “And often there’s a moment when all frequencies are right and it hits.”

To find those moments, Frankenthaler worked in fits and starts—periods of fertile activity followed by stretches of labored, unsatisfactory painting, or nothing at all. “I tend to focus on a body of work intensely and one day put down the brush and feel emptied out,” she said. “I realize that I need to shift gears before I paint again.” A small break could be refreshing, Frankenthaler said, but a long one was frightening:

I will often get back to painting after a break and panic and not know where I left off. I seem to start at day one again. I sit around and sharpen pencils, make phone calls, eat handfuls of pistachios, take a swim. I feel I should, must, will paint. It is agony. It is boredom. I become impatient and angry with myself, until I reach a point of feeling I must start, make a mark, just make a mark. Then, hopefully, I slowly get into a new phase of work.

Helen Frankenthaler in her studio, 1969

The artist followed a somewhat similar rhythm in the kitchen. She said that she had more energy and painted best when she ate healthy—but she also needed the “catharsis” of the occasional junk-food binge. “My usual regime is no fat, no salt, no butter, no sugar, no bread, no cream, but homemade skim-milk yogurt,” Frankenthaler told the authors of a 1977 cookbook. But when she had denied herself for long enough, she would indulge in chocolate, ice cream, or one of a variety of snack foods: “Processed cheese, kosher dill pickles, peanut butter, cheap sardines, and bologna—junk food; these are things that I periodically crave and give in to.”

One of the most celebrated American singers of the twentieth century, Farrell was a classically trained soprano who successfully performed both classical and popular music over the course of her sixty-year career. When she sang at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City, Farrell had a pre-performance routine that she always followed. At about midday, she went into the music room of her home in Staten Island and sang through the entire opera she would be performing that evening. “Some people think this is crazy,” Farrell wrote in her 1999 memoir, “but I say if you’re going to be singing high Cs that night, you’d better make sure they’re in place that afternoon.” In the late afternoon, she took the Staten Island Ferry to Manhattan and caught a taxi to the Met. Although many opera singers are careful to eat a very light meal, or nothing at all, before singing, Farrell was not so dainty. “There was a little restaurant across the street where I would always go for a six-o’clock dinner,” she wrote.

I usually had the same thing—a steak, baked potato, green salad, and hot tea with lemon. Rich, creamy desserts really clog up your throat, so I would order a dish of Jell-O, which went down very easily. Then I’d go across the street, hit my dressing room, and get into my makeup and costume. The only thing I insisted on having in my dressing room when I arrived was a big bottle of warm Coca-Cola. Once I was in my costume, I would drink a few glasses of warm Coke and start to belch. It’s amazing what this can do for the voice, and as Miss Mac [her longtime voice teacher] always used to tell me, “It saves wear and tear on the rectum.”

In the early 1950s, the renowned opera singer Beverly Sills sang with Farrell in New York—and was scandalized by the belching she could hear coming from Farrell’s dressing room. “Those weren’t discreet burps,” Sills later recalled. “They were more like symphonies.”

Antin began her career as a painter but soon moved into conceptual art, becoming a pioneering figure in video, performance, and installation art. She is best known for the elaborate fictional personae whose lives she led, in costume, for days or weeks at a time. These alter egos included a king, a nurse, and, most famously, Eleanora Antinova, the legendary black prima ballerina of Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, whom Antin invented in the mid-1970s and whose persona she explored for more than a decade through performances, installations, films, plays, and memoirs. Creating fictional selves like Antinova has allowed the artist to, in her words, “get out of my own skin to explore other realities.” But it has also required paring back her own life to the very basics. As she said in a 1998 interview, “Because the one thing that matters most to me in my life, and what I’ve spent most of my life doing, is making art, I’ve had to make the rest of my life fairly simple.”

I teach, I have a husband whom I really love, I have a son, now a daughter-in-law, and I have friends, so I’m lucky. But often I don’t have too much time for them. I work very hard. I get five hours of sleep a night—if I’m lucky—but I’m always working, there’s just not much time left for anything else. So I live in my head, making up stories. I really prefer spending my life in what you might say—with not a little touch of irony—is a “traditional” woman’s way of living, like those eighteenth- and nineteenth-century women who were stuck in their roles and their class because they couldn’t escape, so they wrote romantic novels. But in my case I’ve chosen that way. My personae, my historical fictions, are actually all the lives that I’m not going to live because I chose not to. . . . To me, the uninvented life, to paraphrase the cliché, is hardly a life.

Antin figured all this out relatively early in her career—as she said in a 1977 interview, “It seems to me you have to have your personal life organized so that it takes as little of your time as possible. Otherwise you can’t make your art. And if you’re an artist, I don’t care what they say, you should be married to an artist. If not, forget it. If you aren’t married to an artist, what would you talk about?”

Wolfe is a New York–based composer who won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for her oratorio Anthracite Fields, which evokes the lives of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Pennsylvania coal miners. She works at home in the TriBeCa loft she shares with her husband, the composer Michael Gordon, with whom she cofounded (along with David Lang) the new-music collective Bang on a Can in 1987. The married composers each have small studios on opposite ends of the loft, and although their schedules do not always overlap, “there’s a good chunk of the day when we’re both working in our little caves,” Wolfe said in 2017. Her ideal working day begins at 7:30 or 8:00 a.m., when she gets up and takes the family dog out for a walk along the Hudson River. Then she has breakfast and coffee and gets to work. When Wolfe is on a deadline, she’ll work on a new composition around the clock, often right up until bedtime at 11:00 p.m. or midnight, but she considers the morning her prime window of opportunity. “I just feel like my mind is clear,” she said. “I’m not a fuzzy morning person—I mean, I’m physically fuzzy; I don’t find that I want to exercise. But in terms of just putting my mind to work, it’s the best time.”

If she doesn’t have other commitments, Wolfe will compose from about 9:00 a.m. until the early afternoon. In her studio, she has an upright piano, a small desk with a large-screen computer monitor, and bookshelves with scores, music books, CDs, and notebooks; she uses the notebooks to write down ideas about the piece she’s working on (and she generally works on one piece at a time, preferring a long immersion in a single composition). She doesn’t have email access on her desktop computer, and though she can—and often does—check her email on a laptop computer she keeps in the studio, she tries to put off dealing with it until later in the day.

In the afternoons, Wolfe may have teaching duties—she is a professor of music composition at New York University’s Steinhardt School—or she may work with her colleagues at Bang on a Can’s Brooklyn headquarters, or host a rehearsal at home. (Since the family dog wails at high-pitched sounds, this requires a trip to the local doggie daycare first.) Sometimes in the late afternoon she’ll take a walk, a fruitful activity for her work. But perhaps the most crucial component of her working life is the feedback that she and her Bang on a Can cofounders routinely trade among themselves. The three of them are in the habit of running musical ideas by one another, sometimes holding the phone up to their computer speakers to play something and get a quick second opinion. This is not mere positive reinforcement; all three composers are opinionated, and they do not go easy on one another—which, Wolfe said, is what makes the arrangement so valuable. “There’s this very tough dialogue that’s going on pretty regularly,” she said. “And I really cherish that. I think that kind of dialogue lights a fire under you.”

The Berlin-based British composer usually wakes up at 7:00 a.m., has coffee and breakfast, and gets immediately to work in her home office. “I find I’m most creative in the morning, so I try to not do anything other than think about composing in the morning,” she said in 2017. Many days, this requires a conscious application of willpower. “I have to deliberately not let myself do other things when I need to compose,” Bray said. “Very often, I need to just sit looking at the music for a few minutes first, and try to empty my head.” She’ll tell herself, “This is what I’m doing now.” Typically, Bray will compose until lunchtime, at about 1:00 p.m. Then, if she’s on a deadline—or if the work is going particularly well—she’ll “carry on a bit” after lunch. But normally the afternoon is for the administrative chores she avoids thinking about in the morning—in particular, dealing with the emails that have been piling up while she works.

When she’s composing, Bray moves among the piano, the cello—her main instrument—and her desk, where she’ll usually sketch ideas by hand first; she won’t switch to the computer until about two-thirds of the way into the process. Unless she’s traveling, Bray works six mornings a week, and doesn’t often find herself stuck or blocked; even so, new compositions proceed slowly. A good morning’s work might yield thirty seconds to a minute of music, but then the next few days are often spent reviewing and fine-tuning those ideas. (A twenty-minute cello concerto will take Bray about six months to complete.) Although she works in a very methodical, orderly fashion, Bray said that the process doesn’t feel at all straightforward. “Personally, I need a routine, and I need to make myself do it,” she said. “It’s not like I expect it to just come naturally.”

The Texas-born, Los Angeles–based artist’s sculptural assemblages grow out of her fascination with materials—with how they transform from one state to another and how they interact with the human body, in a literal sense and in more esoteric ways. “That’s why I’m interested in making physical objects,” Dunham said in 2017. “I really believe that objects can carry energy, and that they can change internal human dispositions.”

Dunham’s creative process is guided by her own disposition on any given day. She typically wakes up at about 7:00 a.m. and stays in bed until 7:30, when she heads into the kitchen of her combined studio/residence to make a “tonic” whose ingredients vary depending “on what I need for that day,” she said. “I might wake up and feel really airy and need to be grounded—so then I might put apple-cider vinegar or greens in the tonic, to sort of weigh me down. Then there are other days where I wake up and feel heavy, so I need something light. It’s a kind of check-in. The liquid reflects how I’m doing, almost like a mirror.”

Next, Dunham heads out to the small backyard behind her building, to write for about twenty minutes. “It’s basically just putting the pen on the piece of paper and trying to let something come through you,” she said. Then she eats breakfast—often oatmeal—before getting dressed for the day. “I always dress up for work,” she said. “I never work in sweatpants or something like that. I’ll wear heels; I usually look very formal when I’m working. Because I think that also helps shift my energy. . . . It’s another way of thinking about how you are, the state that you’re in, if you’re able to do this type of work, how your day would be best spent based on your internal composition.”

And then she gets to work. For the first part of the day, this often involves a lot of running around Los Angeles, picking up or dropping off objects or materials for her work, or meeting with suppliers or other collaborators. The making part of the equation usually starts at about 4:00 p.m., by which time Dunham is back in her studio and ready to focus on constructing a new sculpture or modifying one in progress. There is also time pressure by now: Dunham will have made dinner plans, so the late afternoon is “crunch time,” and she’ll work up to the last minute before she has to leave for dinner (or before guests begin to arrive, if she’s hosting). After dinner, she will often go back to work, but that time is usually reserved for computer-based tasks. Bedtime is at about 11:00 p.m.

Dunham usually skips lunch, but she may make a smoothie in the afternoon, and she continues to drink variations on her morning tonic as needed throughout the day. If she feels stuck in her work she’ll sometimes use “treats” to kick-start things. “Earl Grey is a treat,” she said. “Chocolate is a treat. . . . Marshmallows are a treat.” Another thing she uses to get out of a rut is dancing. “If I get into a weird zone during the day or I feel stuck, I’ll make a choreographed dance routine,” she said. “Sometimes I’ll record it and sometimes I won’t.” Other types of exercise don’t particularly appeal to her. “I don’t take walks and I don’t exercise,” she said. “I don’t like it. I want to like it, but I don’t.”

Dunham stresses that this schedule applies only when she’s in Los Angeles—she travels frequently, and has also made work in London, New York, and Texas—and that it could be completely different by the next week. “I think my time isn’t organized by day or by hour,” she said. Indeed, she works seven days a week, and doesn’t consider weekends any different from weekdays. She will occasionally take days off from making her sculptures, but that’s a decision she’ll make the morning of. Once again, it’s her internal state that’s the deciding factor; she needs to be in “an energetic disposition” in order to handle her artworks properly. Ultimately, she sees herself less as her sculptures’ maker and more as their facilitator. “It’s like I’m working for the objects,” she said. “I’m just trying to support them in the things that they need in order to communicate as efficiently as they can.”

Allende starts each new book on January eighth, the day in 1981 that she began writing the letter to her dying grandfather that eventually became her first novel, The House of the Spirits. “To have a starting date, which started as a superstition because it was a lucky day for me, is now a matter of discipline,” the Chilean American author said in 2016. “I have to organize my life, my calendar, everything around that day. I know that on January eighth I’m cut away from everything, sometimes for months.”

This period of seclusion, during which Allende refuses trips, lecture invitations, interviews, and other impositions on her time, lasts only until the first draft is done; after that, she is less strict about her time, although she still writes every morning, weekends included, from shortly after waking until lunchtime. “I’m a morning person,” she said. “I get up at 6:00, sometimes before. . . . I have my coffee with my dog, and then I get dressed and I put on makeup and high heels, even if nobody is going to see me—because it puts me in the mood of the day. If I stay in pajamas I won’t do anything.”

Allende works in a two-room home studio in the attic of her house in the San Francisco Bay Area. One room contains all of Allende’s research for her book-in-progress, and all of her beads—the writer is also an avid maker of bead necklaces, which she loves to give away to friends. In the other room she has an altar and a big desk with a computer that’s not connected to the Internet. “It’s just for the writing,” she said. “It only contains the book and the research.”

At lunchtime, Allende stops writing, has a quick meal at home, and begins attending to the myriad demands of being the world’s most widely read Spanish-language author, which usually starts with a review of emails forwarded by her assistant. The remainder of the afternoon is less structured. If there’s not much going on, Allende may write all afternoon, or continue the research that undergirds all of her books, fiction and nonfiction. Otherwise, the only other essential component of her day is a twice-daily walk with her dog, during which she avoids thinking about her writing project. In the evening, she makes herself a simple dinner and goes to bed at 10:00 or 11:00 p.m. “I have this fantasy that after a working day I will sit down and have a wonderful meal with a glass of wine and listen to music,” she said. “Forget it. I have time to wash my face and drop in bed.”

Although she writes for several hours a day, seven days a week, Allende’s current schedule is relaxed by her standards. When Allende was writing The House of the Spirits, she was also working full-time as a school administrator and raising her two children, “so I would write only at night, although I’m not a night person, and on the weekends.” (She worked at a portable typewriter on her kitchen counter.) When she finally quit that job to dedicate herself to writing full-time, Allende maintained an intense schedule, writing Monday to Saturday from 9:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m., and sometimes until later if she was deep into a particular scene. Allende admits now that she may have been putting too much pressure on herself, a consequence of being raised by her grandfather, a disciplinarian who impressed on her the necessity of hard work. “That was very good for me, because it carried me through many ups and downs in my life,” Allende said. “But now that I’m finally stable and at peace and I have a very good life, and I have written so many books, I don’t feel that I have the duty to keep forcing myself to do stuff.” On the other hand, she doesn’t see herself retiring; even after more than twenty books she still enjoys the process. “That’s why I do it,” she said. “Of course I love telling a story. I love it.”

In interviews over the years, the London-born novelist has said that she doesn’t write every day—and although she sometimes wishes she had that compulsion, Smith also recognizes the value of writing only when it feels necessary to her. “I think you need to feel an urgency about the acts,” she said in 2009, “otherwise when you read it, you feel no urgency either. So, I don’t write unless I really feel I need to.” Even when Smith does feel that urgency, she writes “very slowly,” she said in 2012, “and I rewrite continually, every day, over and over and over. . . . Every day, I read from the beginning up to where I’d got to and just edit it all, and then I move on. It’s incredibly laborious, and toward the end of a long novel it’s intolerable actually.”

Smith has also been vocal about the difficulty of writing in a world of infinite digital distractions, and in the acknowledgments section of her 2012 novel NW she thanked two pieces of Internet-blocking software, called Freedom and Self Control, for “creating the time.” She does not use social media, and as of late 2016 she did not own a smartphone, and had no plans to acquire one. “I still have a laptop, it’s not like I’m a nun,” Smith said, “I just don’t check my email every moment of the day in my pocket.”

The Booker Prize–winning author of Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, as well as several other novels and a memoir, Mantel finds fiction writing an all-consuming and thoroughly unpredictable activity. “Some writers claim to extrude a book at an even rate like toothpaste from a tube, or to build a story like a wall, so many feet per day,” the English author wrote in 2016.

They sit at their desk and knock off their word quota, then frisk into their leisured evening, preening themselves.

This is so alien to me that it might be another trade entirely. Writing lectures or reviews—any kind of nonfiction—seems to me a job like any job: allocate your time, marshall your resources, just get on with it. But fiction makes me the servant of a process that has no clear beginning and end or method of measuring achievement. I don’t write in sequence. I may have a dozen versions of a single scene. I might spend a week threading an image through a story, but moving the narrative not an inch. A book grows according to a subtle and deep-laid plan. At the end, I see what the plan was.

Mantel writes every morning as soon as she opens her eyes, seizing the remnants of her dream state before it dissipates. (Sometimes she wakes up in the middle of the night and writes for several hours before going back to sleep.) Her writing days tend to fall into one of two categories: “days of easy flow,” which “generate thousands of words across half a dozen projects,” and “stop-start days,” which are “self-conscious and anxiety ridden, and later turned out to have been productive and useful.” She writes by hand or on the computer, and considers herself “a long thinker and a fast writer,” which means that a lot of her writing day is spent away from her desk, on the thinking part. When she does sit down at the computer, Mantel will sometimes “tense up till my body locks into a struggling knot,” she wrote in 2016. “I have to go and stand in a hot shower to unfreeze. I also stand in the shower if I get stuck. I am the cleanest person I know.”

To other writers who get stuck, Mantel advises getting away from the desk: “Take a walk, take a bath, go to sleep, make a pie, draw, listen to music, meditate, exercise; whatever you do, don’t just sit there scowling at the problem,” she has written. “But don’t make telephone calls or go to a party; if you do, other people’s words will pour in where your lost words should be. Open a gap for them, create a space. Be patient.” Over the course of her career, Mantel has learned extraordinary patience: She first began considering a series of novels based on the life of Thomas Cromwell in her twenties but didn’t begin writing the first of them, Wolf Hall, until thirty years later. (When she finally began writing it, however, she worked with tremendous speed, cranking out the four-hundred-page book in five months, working eight to twelve hours a day.)

“Sometimes people ask, does writing make you happy?” Mantel told a visiting reporter in 2012.

But I think that’s beside the point. It makes you agitated, and continually in a state where you’re off balance. You seldom feel serene or settled. You’re like the person in the fairy tale The Red Shoes; you’ve just got to dance and dance, you’re never in equilibrium. I don’t think writing makes you happy. . . . I think it makes for a life that by its very nature has to be unstable, and if it ever became stable, you’d be finished.

As a student at the San Francisco Art Institute in the early 1980s, Opie worked for her room and board at a residence club in the city, “a druggie, fucked-up place,” she said in 2016. In those days, Opie got up at 2:30 a.m., worked at the front desk from 3:00 to 8:00 a.m., had breakfast, and went to school. After school, she had a job at an early-childhood education program at the YMCA. She worked there until about 7:00 p.m., then went home, had dinner, and forced herself to go to bed at 9:00—or else she would skip sleep entirely, instead pulling an all-nighter in the school’s darkroom until it was time to go back on the night shift at 3:00 a.m.

The long hours paid off: Opie is now one of America’s preeminent photographers, probably best known for her portraits of San Francisco’s queer community, although she has also made photo series on surfers, Tea Party gatherings, America’s national parks, Los Angeles’s freeways, teenage football players, and the inside of Elizabeth Taylor’s Bel-Air mansion. Her schedule is more forgiving than it was in her student days, but not that much more; in addition to running a busy art practice, Opie is a tenured professor at UCLA, which doesn’t leave much free time in her week. “I suppose that I would actually like to not have a daily routine,” Opie said. “I would like to have more wandering. But because I’m a professor, a mother, and an artist that runs a full studio, I end up having to have a really incredibly rigid routine.”

As of fall 2016, her routine meant waking up at 5:50 a.m. weekday mornings, getting her teenage son out the door for school, and going to work out or take a tennis lesson. Then, Monday through Wednesday, she goes to UCLA to teach; Thursday and Friday, she heads to her studio. Either way, she is busy until the evening. After work, she has business dinners a few nights a week; otherwise, she’s home with her family. Because her schedule is so packed, she can generally make new bodies of work only during summer, spring, and winter breaks from school. “There hasn’t been any point where I haven’t been able to make work,” she said. “It’s just, you schedule that like you schedule the rest of your life. It doesn’t happen by chance.”

That said, she is looking forward to retirement and the freedom it will bring—Opie and her wife talk about buying an RV and “roaming around National Parks just for the hell of it”—but teaching has also been incredibly important to her, both because she believes in building and mentoring a community of artists and because it gets her out of her own head, which she thinks is essential for an artist. “It’s important to remember that at times there’s a certain kind of solipsism or narcissism within the practice,” she said, “and there are other times where it’s absolutely never about you; it’s about how you deal with your community and your family and the aspects of what it is to be human. So I try to find a really good balance between those.”

The pioneering video and performance artist lives and works in Manhattan, in the SoHo loft she has rented since 1974. Although she doesn’t follow the exact same routine every day, Jonas generally gets up at about 7:30 a.m. and takes her miniature poodle, Ozu, out for a walk. Then she has coffee at a favorite café in the neighborhood and reads the newspaper. Returning to her loft, Jonas goes to work and pretty much continues all day, often with music on in the background. (Morton Feldman is a favorite.) Jonas tries to draw every day, and will often begin her workday by doing that—or if she’s working on a script for a new video, she may do that first thing. If she has assistants coming in, they’ll arrive at about 10:00 a.m. and stay until 6:00 p.m. (Jonas has three part-time assistants: one to help with video editing, one to lay out plans for museum and gallery exhibitions, and one who does various tasks, such as solving construction and installation problems.) Research is also a big part of her working process. “I’m always looking for stories,” Jonas said in 2017. “I read for that reason; I’m doing research. One of my activities is going to the bookstore, getting books, reading books, looking through books for ideas.”

While she’s out, Jonas often carries a small notebook for writing down ideas, or if she doesn’t have a notebook she’ll use her iPhone. But coming up with new ideas is not her main concern. “I think I’ve been using the same ideas over and over again, in different ways,” Jonas said. “It’s a kind of language I’ve developed. So I’m not sure how many brand-new ideas I have, but I reinvent the ideas I’ve already worked with, or put them in a different context.”

Jonas takes an hour-long break for lunch, and her day is punctuated by trips outside with Ozu. “The dog gets walked a lot, several times a day,” she said. “I like to walk around the neighborhood and say hello to a few people who are left here who I know, in the shops. Or go to galleries nearby. But usually I work all day.” In the evenings she sees friends for dinner, and she will host a dinner party at her loft once a month or so. Afterward she reads or watches old films on cable TV or her computer. Bedtime is usually at about 11:00 p.m., but sometimes not until midnight or 1:00 a.m. “And I often can’t sleep so I read during the night also,” Jonas said. “Or look at movies during the night, on my computer.”

Jonas doesn’t ever feel creatively blocked, and she finds that inspiration comes easily and through everyday life—while walking in the park, spending time with friends, going to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, or visiting new places. “I think the way to become inspired is to empty your mind and let things come into your mind,” she said. Inspiration is not, she thinks, something terribly precious or unusual. “I don’t separate inspiration from doing research and becoming interested in something,” Jonas said. “I don’t separate those things into categories. It’s all in the same experience of being curious about the world. That’s what I find inspiring, the world—you know, the world around me.”