My passion for all things sweet began, as it does for most of us, in my childhood. My grandmother would take us into New York City to a restaurant that made the most incredible mile-high Southern caramel cake. I still dream about it. My father would make us Crêpes Suzette if we asked him. The theatricality of it mesmerized us as he made it right at the table with a burner and copper skillet he bought in France just for the purpose of making the dish. He furthered the evolution of our taste for sweets by arriving home with boxes of baklava from a Greek bakery or with quarts of just-made vanilla ice cream from a local farm.

By age twelve, I was baking creamy rice puddings and making ice creams in our family’s old hand-cranked ice cream maker with the sweet peaches from our trees. By the time I was a newlywed living in Paris, I had developed a recipe box full of handwritten cards of all the desserts I loved to make.

Years later when my husband and I returned to France to make it our home, I gained considerable knowledge about French desserts while living there for almost thirteen years, most of that time next door to a neighbor with a sweet tooth. Madame took me on a culinary tour of France’s sweets by tutoring me in her kitchen. She had grown up in Alsace, spent time in Dijon, and moved with her husband to the south of France, so her sweets reflected a wide range of regional specialties.

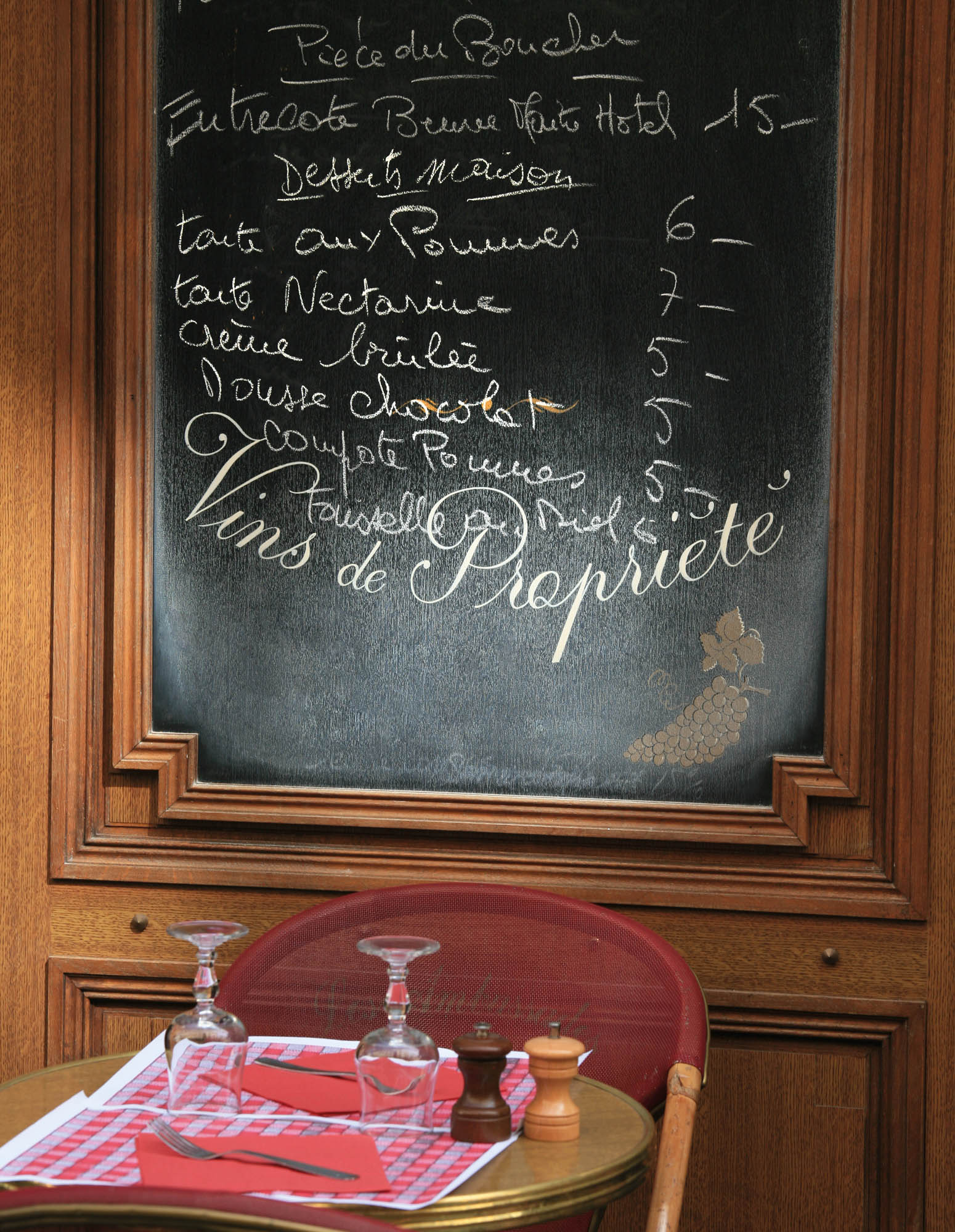

That sparked my interest in learning more about French cuisine and its deliriously delicious desserts. My husband and I traveled extensively throughout the country, and I was always stopping in local pastry shops to search out and sample things I was unfamiliar with, to explore desserts on bistro menus, and to collect recipes and techniques from people I met as I traveled. My dessert trail was filled with crumbs.

I learned that France has many regional desserts that are not found in other parts of the country, some of which date back centuries. Regional desserts, for the most part, reflect the area they are made in, just as any other dish on the table would. Normandy and Brittany are known for their excellent butter, cream, and milk, so their desserts are butter-centric, while in Provence you are less likely to find a rich, buttery dessert. Regional desserts also evolved because a town or area wanted to promote it for tourism or to protect it as a tradition. Many of the regional desserts I had never seen before in cookbooks, so for that reason, and because I fell in love with them, I made every effort to include them in this, my first dessert cookbook.

You will be delighted with the recipe for a Giant Break-and-Share Cookie from the Poitou-Charentes region of France. It is a communal cookie made so that, after town meetings, baptisms, and marriages, everyone can break off a piece to enjoy together. It’s my favorite cookie ever. Absolutely delicious. You will also discover a recipe for a unique triangular anise cookie from Charentes, in the western part of central France that is always made on Palm Sunday. Why three-sided? Some say it is to represent the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. There’s a recipe for a sweet sugar bread from the Ardennes region in northern France as well as one for a beautiful ruffled apple pie, called Pastis Gascon, that they make in southwest France. You’ll also love the recipe for little cakes from the area around Dijon, called Nonnettes, that have an orange marmalade heart.

What I learned over the many years I lived in France and from my extensive traveling throughout the country, is that French desserts—the ones the French make in their homes—are easy to make. Sophisticated pastries are a high art in France and with so many wonderful pastry shops within a short walk, the French simply buy them. They don’t make them at home. What they do make at home are the desserts they grew up with—simple, homey comfort food desserts.

With my guidance you will be able to make them in your home kitchen, without fuss or intricate methods or special ingredients. To organize them, I divide each chapter, first into the recipes that are quicker to make, followed by the recipes that take longer to make. And, for the few fancier creations, I worked to demystify the magic of making them. For example, instead of presenting you with a traditional recipe for a millefeuille, a complicated and very popular pastry in France, I created one for you to make that is simpler than making cookies and is spectacular when brought to the table.

During a recent interview, a journalist asked me if there was a common theme between the four French cookbooks I have written, and I replied that there is. It is that I wanted to emphasize that French cooking is home cooking. The French go to fancy restaurants if they want fancy food, but for everyday dining, they celebrate simple food made at home, because they treasure their time at the table with family and friends, and they love to cook for them. Cooking and eating together is a ritual they honor. And the food they honor is the food their grandmother or mother made for them—casual rather than formal, free form rather than fussy.

A word about ingredients. Since the recipes in this book are for the most part based upon only a few ingredients—flour, butter, milk, eggs, and fresh fruit and berries—you should do as the French do and use nothing but the best. Do this, and your desserts will be simply sensational.

I hope you have a great time with these recipes and that they will inspire you and acquaint you with the fabulous regional desserts of France.

Please feel free to email me with your questions or observations at hillarydavis@me.com, I look forward to hearing from you!