KEITH WOOLNER

I expect the real reason baseball will eventually return to the four-man rotation will be the simplest of all: It helps win games. The five-man rotation is not on that evolutionary path; it’s a digression, a dead-end alley. Just as baseball once believed that walking a lot of batters was better than throwing a home-run pitch, we are now chasing an illusion that our pitchers work better on four days’ rest and that the five-man rotation significantly improves their future.

—Craig Wright, The Diamond Appraised, 1989

If it were an owl, it’d be on the endangered species list. If it were in Manhattan, it’d be an affordable apartment. If it were a baseball player, it’d be a left-handed third baseman.

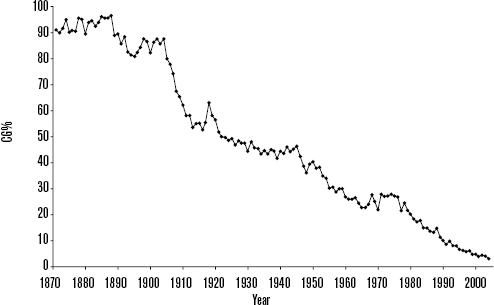

We’re talking about the complete game. Long ago it was a fixture in the big leagues. Today it is nearly nonexistent. Pitchers haven’t finished even half of the games they’ve started since before the Harding administration, and in recent years the number of complete games in the majors has been vanishingly small. The demise of the complete game is almost, well, complete. Why?

Pitchers have been throwing fewer and fewer complete games ever since the day in 1893 when the mound was moved back to 60 feet, 6 inches.

FIGURE 2-3.1 Complete game percentage

In 2004, the percentage of complete games dropped below 4 percent for the first time—meaning the starting pitcher finished less than one game in twenty-five (Table 2-3.1).

TABLE 2-3.1 Starts Resulting in Complete Games over the Past One Hundred Years

Furthermore, pitcher specialization is on the rise, which will surprise no one who has ever tuned in to a Tony LaRussa three-and-a-half-hour, five-pitching-change special. Not only are starters going fewer innings, but it’s taking more relievers to get through the rest of the game (Fig. 2-3.2).

So are modern pitchers just less durable than their predecessors? Are they incapable of shouldering the workloads that men like Charles Radbourne, Jack Chesbro, and Walter Johnson could handle?

FIGURE 2-3.2 Pitchers used per game

There is anecdotal evidence that pitchers in the past did not use maximum exertion on every pitch. With the deadball era suppressing offense in the early twentieth century and teams mostly carrying defense-first options at positions such as second base and catcher, pitchers like the legendary Christy Mathewson could pace themselves, letting up at nonessential moments of the game. In his book Pitching in a Pinch, Mathewson described his methods for staying fresh:

I have always been against a twirler pitching himself out, when there is no necessity for it, as so many youngsters do. They burn them through for eight innings and then, when the pinch comes, something is lacking. . . . Some pitchers will put all that they have on each ball. This is foolish for two reasons.

In the first place, it exhausts the man physically and, when the pinch comes, he has not the strength to last it out. But second and more important, it shows the batters everything he has, which is senseless. A man should always hold something in reserve, a surprise to spring when things get tight. If a pitcher has displayed his whole assortment to the batters in the early part of the game and has used all his speed and his fastest breaking curve, then, when the crisis comes he hasn’t anything to fall back on.

With middle infielders often smacking 20, 30, or more homers in a season, and even the worst modern-day hitters still more dangerous than their forefathers, pitchers have to exert more effort with each batter. After six, seven, or eight innings, today’s pitchers often find themselves with higher pitch totals and more fatigued arms than Mathewson and his contemporaries would experience when they’d go the distance.

One of the earliest analyses of historical trends in pitcher usage was the landmark 1989 book The Diamond Appraised by Craig Wright and Tom House. The authors looked at pitchers of various ages and their workloads and discovered that young pitchers who pitched to a high number of batters per game seemed to get hurt more often. This was the beginning of the modern movement to monitor pitch counts.

In the mid-1990s, Baseball Prospectus’s Rany Jazayerli was one of the first researchers to try to organize and codify what the mishmash of evidence on pitch counts was telling us; he summed it up in his principle of pitcher fatigue: Throwing is not dangerous to a pitcher’s arm. Throwing while tired is dangerous to a pitcher’s arm.

In Baseball Prospectus 2001, we showed evidence that even the starting pitchers who regularly work deep into games do decline in performance, as a group, after throwing a high number of pitches. We compared how they pitched in the weeks before such a game to how they pitched in the three weeks after. We found that pitchers throw fewer innings per start, strike out fewer batters, and allow more hits and walks in the starts following the high-pitch outing. We rolled these factors into a formula called pitcher abuse points (PAP):

PAP = (no. of pitches – 100)3 |

for no. of pitches > 100 |

PAP = 0 |

for no. of pitches ≤ 100 |

Through this formula, we can see that as pitch counts grow, they quickly produce unwieldy numbers (Table 2-3.2).

TABLE 2-3.2 Pitcher Abuse Points, by Number of Pitches Thrown

To help manage this numbers explosion, we break starts down into five categories of risk (Table 2-3.3).

As the pitch counts increase, we’ve observed corresponding declines in the weeks following a long start. The reduction in quality may not seem big, but if a staff is regularly asked to go too deep into a game, it may spend much of the season at less than optimum performance levels, costing the team runs and multiple wins. In this respect, PAP is more about the manager and how he handles a staff than about any particular pitcher.

TABLE 2-3.3 Pitcher Abuse Points, Five Risk Factor Categories

But aren’t pitchers paid to pitch? How does having them pitch less help the team?

If you cut a pitcher’s workload by an inning per start over 30 starts, say from 240 innings pitched to 210 IP, and in doing so you reduce his runs allowed by half a run, to 4.00 from 4.50, are you better off as a team? To analyze this dilemma, let’s look at a pitcher through the prism of Value Over Replacement Player. VORP measures the number of runs a pitcher prevents from scoring, above what a replacement-level pitcher—a Triple-A lifer or a fringe player—would be expected to prevent. Because VORP rewards both production and increased playing time, a pitcher would need to show a substantial improvement in production to override the 30 innings he’s now being forced not to throw.

Not that substantial, though. Using (6.50 – RA) × (IP/9) as an estimate of a pitcher’s VORP:

(6.50 – 4.50) × (240/9) = 2.00 × 26.67 = 53.3 VORP

(6.50 – 4.00) × (210/9) = 2.50 × 23.33 = 58.3 VORP

If this pitcher’s workload is reduced by 30 innings, his team actually gains about 5 runs, or half a win, over a full season, assuming his pitching less often cuts half a run off his run average (ERA minus the impact of errors, see Chapter 2-1 for more on RA). But this assumption doesn’t always hold: Sometimes the gain in RA does not offset the loss of innings pitched. Suppose that instead of half a run the pitcher only improved by a tenth of a run in RA (0.10).

(6.50 – 4.50) × (240/9) = 2.00 × 26.67 = 53.3 VORP

(6.50 – 4.40) × (210/9) = 2.10 × 23.33 = 49.0 VORP

At this point, it looks as if the team is probably better off pushing the starter for those extra 30 innings, depending on the quality of the bullpen. There is a break-even point between a pitcher’s lost innings and his increased effectiveness. Fortunately for major league managers, the innings lopped off the ends of pitchers’ totals would occur late in games, with the skipper typically coming out in the seventh, eighth, or ninth inning to bring in a fresh reliever. The manager has the luxury of knowing whether he is in a tight contest or a blowout. Judiciously removing pitchers earlier in games where those extra innings are not high leverage—that is, the game is not close—thus helps keep the staff fresh for when its pitchers really need to bear down.

And then there’s the risk of injury—whether or not the pitcher is around to throw those innings we’d like him to pitch. Once again we return to the principle of pitcher fatigue: Throwing is not dangerous to a pitcher’s arm. Throwing while tired is dangerous to a pitcher’s arm.

Just as certain kinds of workloads create a risk of ineffectiveness in the short term, they can also create a higher risk of injury. As another part of the study in Baseball Prospectus 2001, we compiled a list of pitchers who had gotten injured as well as healthy pitchers of similar age and total career workload. When we compared the injured pitcher to his healthy counterparts, we found that the injured pitcher tended to have accumulated more PAP over his career. In other words, given two starting pitchers who have thrown a similar number of pitches in their careers, the one who pitched more high-pitch-count games was at greater risk of injury.

We capture this occurrence in a metric called stress, which is simply PAP divided by total pitch count. Stress usually ranges from zero to 100, although a few exceptional cases of stress levels above 100 have happened. To see the relationship between stress and injury, we took all the pitchers analyzed, ranked them in order of stress, and looked at a moving average of the percentage of pitchers who were injured around a given stress level (Fig. 2-3.3).

The trend shows a sharply increased risk of injury as stress levels climb from zero to 30 or so, followed by a tapering off but still largely increasing risk. There are very few pitchers in the region above 80 stress, so an outlier like Livan Hernandez or Randy Johnson can have a distorting effect on the overall results because there are so few comparable pitchers to examine.

FIGURE 2-3.3 Average injury rate as a function of stress of workload (50-point forward averaging)

One important lesson from the PAP research is that not all pitchers have the same injury risk. What we’re looking at is the aggregate result of pitchers with differing capabilities, physiques, and endurance. Livan Hernandez may be able to throw 130 or more pitches without ill effects, while Pedro Martinez may suffer when asked to go more than 90; this could be due to body type or any number of different factors. PAP and stress give us a general indication of how pitchers, as a group, respond to different workloads. They are a useful baseline from which to work, but they do not directly incorporate additional knowledge about a player’s physical capabilities. There’s still much research to be done to help us determine each specific pitcher’s capacity and threshold. Biomechanical studies by people like Dr. Glenn Fleisig at the American Sports Medicine Institute could one day bridge the gap.

But there are right and wrong ways to protect pitchers’ careers. If we accept that high pitch counts increase the risk of pitcher injury, does it not follow that starting on three days’ rest is more dangerous than starting on four days’ rest?

No, it doesn’t. The risk from high pitch counts comes from the pitcher being fatigued. The standard five-man rotation in use today typically gives starting pitchers four days between starts. A generation ago, four-man rotations that gave pitchers three days of rest were more common. One advantage of the four-man rotation is that it gets your best pitchers more starts. As the five-man rotation has taken hold, the starter who gets 36 or more starts has become as rare as a complete game (Table 2-3.4).

TABLE 2-3.4 Pitchers with 36 or More Starts in a Season, 1969–2004

In the past twelve years combined, there have been fewer pitchers with 36 starts in a season than in any individual season between 1969 and 1980. Starts that used to go to the number 1, 2, and 3 pitchers are now going to lesser arms. Contrast the distribution of starts between 1974 and 2004 shown in Table 2-3.5.

Compared to thirty years ago, teams in 2004 are giving more starts to swing-men, emergency starters, and failed experiments. Their top three pitchers are accounting for roughly twelve fewer starts today than three decades ago. Twenty-first-century teams have taken 8 percent of the season away from their best arms and given it to replacement-level players.

The original thesis of this chapter was that a fatigued pitcher sometimes loses his mechanics, which in turn causes strain on his arm and creates the risk of injury. Teams can mitigate that risk by ensuring that a pitcher does not spend an undue amount of time pitching while fatigued, and giving him enough rest between outings to fully recuperate. Since we’re so concerned with preserving pitchers’ health by providing better rest, doesn’t it stand to reason that the performance of pitchers on four days of rest would justify the lost innings?

No, it doesn’t. There’s no medical evidence that four days of rest are better than three for allowing the pitcher’s body to recover. Furthermore, relief pitchers, even long relievers, don’t get four days of rest before they’re considered available again.

TABLE 2-3.5 Distribution of Starts per Rotation Slot, 1974–2004

Since 1972, 175 pitchers have tossed 408 seasons with at least 8 starts on both three and four days of rest. Weighting each pitcher’s season (so that pitchers who routinely threw on three days of rest—usually the best pitchers—are not overrepresented) shows that this group actually did better in most important categories on three days of rest than on four days of rest:

![]() Winning percentage was 0.014 higher (.539 vs. .525, a 2.60 percent improvement).

Winning percentage was 0.014 higher (.539 vs. .525, a 2.60 percent improvement).

![]() ERA was 2.4 percent lower, 3.54 versus 3.62.

ERA was 2.4 percent lower, 3.54 versus 3.62.

![]() RA, which includes unearned runs, was 2.2 percent lower, 3.93 versus 4.01.

RA, which includes unearned runs, was 2.2 percent lower, 3.93 versus 4.01.

![]() Strikeout rate (–0.44 percent) and walk rate (+0.7 percent) were each slightly worse.

Strikeout rate (–0.44 percent) and walk rate (+0.7 percent) were each slightly worse.

![]() Home runs per inning was 4.1 percent lower.

Home runs per inning was 4.1 percent lower.

![]() Opposing batters hit .254/.306/.269 against these pitchers on three days of rest; they hit .254/.305/.274 on four days of rest—virtually identical.

Opposing batters hit .254/.306/.269 against these pitchers on three days of rest; they hit .254/.305/.274 on four days of rest—virtually identical.

![]() These pitchers threw just as deep into the game (6.90 innings on three days versus 6.86 innings on four days—a tiny difference).

These pitchers threw just as deep into the game (6.90 innings on three days versus 6.86 innings on four days—a tiny difference).

The only category in which there was even as much as a 3 percent difference between the two sets of performances was in home runs per inning—and that was a 4 percent difference in favor of three rest days. But rather than trumpet these small differences as proof that pitchers actually perform better on three days’ rest, let’s simply conclude that there’s no evidence to suggest that starting on three days’ rest hurt these pitchers’ performance.

But perhaps we’re focusing on the wrong group of pitchers. We’re looking at a group that started a minimum of sixteen times, whose managers asked them to do so at least eight times on three days’ rest. Perhaps the pitchers who weren’t counted on to start on short rest did noticeably worse. Back to the data.

There have been 879 pitchers who were asked to start between one and eight games on three days’ rest while making at least one other start on four days’ rest. Comparing their performances on three versus four days of rest (again weighting them to prevent overrepresentation), we do find that such pitchers do slightly worse on three days’ rest. Vindication for common wisdom? Hardly. The difference in every category is still less than 3 percent.

![]() ERA was 4.47 on three days’ rest vs. 4.38 on four days’ rest.

ERA was 4.47 on three days’ rest vs. 4.38 on four days’ rest.

![]() RA was 4.84 versus 4.70.

RA was 4.84 versus 4.70.

![]() Hits, walks, strikeouts, and home runs were all less than 2 percent different.

Hits, walks, strikeouts, and home runs were all less than 2 percent different.

![]() Opponents hit .269/.324/.408 on three days of rest versus .267/.321/.406 on four days of rest.

Opponents hit .269/.324/.408 on three days of rest versus .267/.321/.406 on four days of rest.

Even pitchers who rarely threw on three days of rest achieved a level of performance very similar to what they achieved when they were given “full” rest.

Another possible objection to the four-man rotation is that pitchers will tire more over the course of a season—that their performance in September will suffer more than their performance in April and May would. This is also false. We looked at all pitchers who started at least 30 games who made more than half their starts on either three days’ rest or four days’ rest. We then compared how they performed through the entire season until Aug. 31 to how they performed in regular-season games in September and October (Table 2-3.6).

Pitchers in a four-man rotation actually reduced their RA and ERA slightly more than pitchers in a five-man rotation did. For the most part, the differences between the September performances of the two groups are slight. Five-man rotations did better in strikeouts, while four-man rotations were much better in preventing home runs. There’s no indication that pitchers suffered disproportionately late in the season when pitching in a four-man rotation.

TABLE 2-3.6 Performance on Three Days’ vs. Four Days’ Rest in September and October Compared to the Rest of the Seasona

But wait, you say; you can’t expect pitchers who’ve grown up and pitched all their careers in five-man rotations to suddenly make the switch to a four-man rotation. The changes in their preparation, routines, and demands on their bodies are simply too difficult to accommodate. The truth is that we expect pitchers to make even greater changes every year and rarely give it a second thought. They are frequently taken out of the rotation and moved to the bullpen, or vice versa. Most minor league pitching prospects progress through the system as starters, particularly early in their careers. Even if their organization had projected them as relief pitchers in the majors, the players worked regularly in the starting rotation to ensure a consistent usage pattern.

Starting and relieving have very different requirements. Starters know when they are expected to pitch, and do so until they tire or lose effectiveness. Relievers work in shorter outings but often have only minutes of warning before they are called upon to pitch. They may work several days in a row or be left in the pen for a week or more, but they’re still expected to be sharp when needed. Yet pitchers switch roles all the time.

Eric Gagne, Tom Gordon, Miguel Batista, Dave Righetti, Jeff Russell, LaTroy Hawkins, and Tim Wakefield all converted from starter to reliever in a season or less and found success. Derek Lowe, Kelvin Escobar, Bob Stanley, and Billy Swift moved from being closers to pitching in the starting rotation. John Smoltz has done it both ways, converting from a Cy Young–caliber starter to a dominating reliever and then back to a very successful starter a few years later. Pitchers can clearly adapt to much bigger changes in their usage patterns than a four-man rotation would require.

On the other hand, consider what a team can gain by abandoning the five-man rotation. Using some comparisons between the pitcher usage in the early 1970s and the early 2000s to estimate what a four-man rotation would look like, we can make some educated guesses.

![]() Thirteen starts currently being given to fifth starters or worse are instead made by the top three starters.

Thirteen starts currently being given to fifth starters or worse are instead made by the top three starters.

![]() About 10 runs are saved by a combination of the better RA of the top three starters and by the extra innings they pitch, taking innings away from the shallow end of the bullpen.

About 10 runs are saved by a combination of the better RA of the top three starters and by the extra innings they pitch, taking innings away from the shallow end of the bullpen.

![]() The bullpen has to throw fewer innings, reducing the wear and tear on those pitchers who don’t have the luxury of a predictable schedule.

The bullpen has to throw fewer innings, reducing the wear and tear on those pitchers who don’t have the luxury of a predictable schedule.

![]() The manager has an extra roster spot to spend as he sees fit. That could be a position player, such as a platoon partner, a defensive replacement, or a pinch-hitting specialist, or an extra pitcher to further spread the work around in the bullpen.

The manager has an extra roster spot to spend as he sees fit. That could be a position player, such as a platoon partner, a defensive replacement, or a pinch-hitting specialist, or an extra pitcher to further spread the work around in the bullpen.

In our scenario, the direct benefits in run prevention and needing fewer bullpen innings amount to about one and a half wins in the standings. The strategic benefit of having an extra roster spot could potentially be as great, but let’s be conservative and say that the best use of that roster spot is worth 5 runs, or about another half win. A 20-run or two-game swing obtained solely by better usage of players already on a team is a gigantic advantage—akin to replacing Endy Chavez’s bat with Andruw Jones’s in 2004.

But with the four-man rotation comes the responsibility to vigilantly monitor pitch counts and fatigue levels. Consider the 1995 Kansas City Royals, perhaps the most recent team to try a four-man rotation for an extended period. Manager Bob Boone stuck with a four-man rotation of Kevin Appier, Mark Gubicza, Tom Gordon, and Chris Haney for most of the first half of the season. The experiment looked successful at first; at the end of June, Appier was a Cy Young candidate with an 11-3 record and a 2.30 ERA. Haney (2.82 ERA), Gubicza (3.38 ERA), and Gordon (4.02 ERA) were also more than respectable.

Then the wheels came off. The best ERA managed by any of the four after July 1, Gubicza’s 4.02, equaled the worst any of them had posted prior to that point. Gordon’s ERA rose over half a run to 4.66. Haney started only three more games with a bloated 9.22 ERA before being lost for the season. Perhaps most disappointingly for Royals fans, staff ace Appier had a 4-7 record and a 5.79 ERA the rest of the way, including a stint on the disabled list with shoulder tendonitis.

Do pitch counts give us any insight into what happened? Mark Gubicza, the Royals’ most consistent starter throughout the year, was also one of the best handled, topping out at a single start of 120 pitches and two of 119, but otherwise routinely throwing 100 to 115 pitches per game. Chris Haney was handled even more carefully, never throwing more than 109 pitches, before succumbing to a herniated disc in his back. He’s a good example of how tracking pitch counts, while a useful tool for reducing injuries, cannot completely prevent them.

Tom Gordon was worked considerably harder. He pitched three category-IV starts (significant risk of decline) in the span of a month, starting with a complete game, 1-run effort in 124 pitches on June 16. The stretch culminated in a 131-pitch outing in which Gordon surrendered 4 runs in less than seven innings on July 18. His stress factor (PAP per pitch thrown) for the season as of July 18 was 43, his ERA 3.83. Gordon’s ERA from June 16 to July 18 was a solid 3.02—but his stress was a high 65. He put up a 5.11 ERA over the rest of the season.

Appier fared even worse. Beginning on May 13, his pitch counts were 132, 131, 112, 123, 125, 109, 122, 141, and 133. That streak of two category-V and five category-IV starts in a span of nine appearances took its toll. His stress factor for the year after the 133-pitch start was a staggering 145. His ERA stood at 2.20, but it would swell to 5.38 over the rest of the season, despite his throwing 7.1 shutout innings in just 98 pitches in his next start. Following that effort, he managed only one decent start in the next six, including giving up 10 runs in 3.2 innings, 6 runs in 2 innings, and 7 runs in 6 innings before landing on the disabled list with shoulder tendonitis. Appier was kept on a much shorter leash after he returned, topping 115 pitches only once during the rest of the season. But the damage was done. Kevin Appier’s 1995 season, and the Royals’ season generally, is an example of how not to run a four-man rotation. You can run your starters out there every fourth day, but don’t expect them to go all nine innings if you want them to thrive for the full season.

The complete game is a relic of another era because we know more about why pitchers get hurt. Throwing while tired is particularly dangerous to a pitcher’s arm. We’ve seen this both by looking at the risk of arm injury and by observing declines in pitcher performance following high-pitch-count games. But this doesn’t mean that starting pitchers are doomed to become forever more fragile. By pulling starters more aggressively as their pitch counts and fatigue levels rise, and shifting to a four-man rotation to give them adequate but not excessive rest, we can keep pitchers healthy and effective, see a return of the 275-inning season (which the majors haven’t seen since Reagan was in office), and improve teams’ roster management as well.