Spotsylvania, May 13, 1864. (After Karamales)

If Grant had been checked by Longstreet’s timely arrival on the field on May 6, he had not been deterred. The indecision of the battle and its heavy losses, while disappointing, had not dulled his relentless objective to hang onto Lee until he had ground him to bits. His men were not so sure. That evening gloom enfolded the army that had gone into the battle with such high hopes. It was Chancellorsville all over again, almost literally—the same field and approximately the same number of casualties—15,000—and the same failure, for Bobby Lee had bloodied them badly. On the morning of the 8th, the army was on the road again with black failure hanging over it, bitterly expecting to march north to lick its wounds one more time. Grant and his staff rode past the troops of Hancock’s II Corps, aides shouting, “Give way to the right!”

And suddenly the soldiers realized that the generals were riding south. South: that meant no retreat, no defeat, maybe the battle had been a victory after all even though it had not exactly felt like one … and the men of the Second Corps sprang to their feet and began to cheer, and kept on cheering as long as they had breath for it. For the first time, Grant won a spontaneous applause of the Army of the Potomac.43

Grant kept moving southeast around Lee’s flank, reaching for Spotsylvania Court House, but Lee, unbeknownst to him, was quicker off the mark. Even after Maj. Gen. Gouveneur Warren’s V Corps had captured several of Longstreet’s men in skirmishes on the roads leading to the Court House, as William Feis observes, “the army commander brushed off Warren’s report, remarking, ‘I hardly think Longstreet is yet at Spotsylvania.’” Even by the next morning the report had not filtered down to Hancock, who was at Todd’s Tavern beyond the army’s right flank.44

As it was, Grant’s advance corps nearly got to the Court House first, but Lee’s men beat them by a hair to the surprise and chagrin of everyone, not least of all Grant. It was also only dawning on him that V Corps, which should have seized the Court House, was commanded by a man who would prove time after time that he was habitually a day late and a dollar short—Warren. An initial attack to bounce the fresh Confederate positions failed. Grant planned a direct assault on the increasingly formidable Confederate defenses for the 10th as his army closed on Spotsylvania. His chief of staff and alter ego, Maj. Gen. John A. Rawlins, wrote on the 9th, “The feeling of our army is that of great confidence, and with the superiority of numbers on our side, I think we can beat them notwithstanding their advantage of position.”45

Babcock and Sharpe, now reunited at a fixed headquarters, intensified their interrogations to provide critical information prior to the attack. They found themselves at this time deprived of the supplementary information that would have been provided by the Cavalry Corps had it been with the army. Unfortunately, it was absent, the result of a violent argument between Meade and Sheridan. Meade had wanted the corps to continue to guard the army’s flanks and trains. Sheridan wanted to hunt down the Confederate cavalry and had got into a violent shouting match which Meade reported to Grant. The lieutenant general decided to let Sheridan have his chance, and Sheridan galloped off with almost the entire corps to raise hell deep in the Confederate rear. The raid’s greatest achievement was the mortal wounding of Stuart at Yellow Tavern, but it deprived the army at Spotsylvania of an aggressive reconnaissance effort that would have added immeasurably to Sharpe’s own efforts.46

Lee’s army had the amazing ability to throw up deadly field fortifications in almost no time, and that is what faced Grant as his corps arrived on the field. The key to the works was a formation called the Mule Shoe or the Salient in front of the Union VI Corps. Grant decided to strike there. If it cracked, Lee’s entire position would be untenable. The reinforced regiments of Col. Emory Upton’s brigade of VI Corps were massed one behind the other on a narrow front to assault a position in the center of the Confederate line called the Salient or the Mule Shoe, while Hancock and Warren attacked the Confederate III Corps to the left of this position. The Salient formed the apex of a right angle with Ewell’s Corps packed inside. The assault was scheduled for just after 6 p.m. The other two Union corps would attack two hours earlier to fix the enemy’s reserves. Grant figured that the enemy could not be strong everywhere, and that his superior numbers would eventually crack the enemy line. Just before the assault Meade wrote to Grant that “a scout just in from the right says there is no infantry beyond Barlow’s right but a cavalry force at Corbin’s Bridge.” He then dispatched one of Hancock’s divisions to shore up the flank.47

At 3 p.m. Sharpe rushed an interrogation summary to headquarters that identified the enemy forces in the Salient as well as the nature of its defense, confirming and amplifying the visual reconnaissance conducted by Upton and his officers. The report stated Rodes’s and Johnson’s Divisions were defending the perimeter of the Salient and that hidden fortifications made the position extremely strong. The report was precisely accurate. The two divisions in fact defended a perimeter of about 1 mile with a third, that of Gordon, in reserve in the hidden fortifications that cut across the base of the Salient. The prisoners further said that divisions of Hill’s Corps were in deeper reserve to the south, and in fact Hill’s troops manned the right of the Confederate line that dog-legged south from the Salient putting them effectively in supporting distance.48

The VI Corps attack, as described by Major General Humphreys, went in at 6:10 p.m. from the shelter of a wood only 200 yards from the Salient. At command, from its concealed position, the brigade rushed forward with a hurrah under a terrible front and flank fire, gained the parapet, and had a hand-to-hand desperate struggle, which lasted but a few seconds. Then the column poured over the works, capturing a large number of prisoners. Pressing forward and extending right and left, the second line of entrenchments fell into Upton’s hands.

At this moment the VI Corps division held in reserve to exploit just such an opening was stopped cold by heavy Confederate artillery fire as it moved forward. At the same time, Gordon’s Division in Ewell’s reserve line counterattacked. Upton’s men held on but were finally evacuated after dark. He lost a thousand men, but had left the Salient filled with Confederate casualties and brought away 1,000 to 1,200 prisoners. Knight was there to see Upton’s men return in a drizzling rain, especially Upton’s old regiment, the 121st New York, in which he had many friends. “When they came out they could scarcely have been distinguished from negroes, their faces and hands had become so black by biting cartridges and getting the powder smeared on their wet hands and faces.”49

Grant was implacable in his determination to keep striking until the Army of Northern Virginia finally collapsed. The near success of the 10th encouraged Grant to plan an even greater blow on the 12th. Hancock’s II Corps crashed through the Mule Shoe. The fighting was in close quarters between two implacable masses of men that seethed and killed back and forth over the fortifications, leaving heaps of dead and wounded, probably the most intense combat of the war. In the end, Lee was able to throw in enough reserves to push the Union troops out. The men in blue had suffered 9,000 casualties and the Confederates 8,000. Among the 3,000 prisoners was almost the entire old Stonewall Brigade. Scout Anson Carney was there with Grant’s and Meade’s command groups:

… the prisoners were marched into a large open field, being soon after sent to the rear under a strong guard. Half an hour or so later I was ordered to ride after them in haste and secure information if possible with regard to the correctness of a rumor that the enemy had destroyed or burned a large portion of our wagon train. I rode rapidly to the rear. The prisoners had been halted on a hill for a brief rest. I made known my orders to the proper officer in charge. I questioned several of the Johnnies and found there was no truth in the rumor, I returned and reported. But our officers were uneasy, and believed there was something in the rumor, and presently another member of the bureau was dispatched after the prisoners on the same errand. When he returned he corroborated my report.50

In this episode is an indication of the problem that plagued the BMI for the rest of the campaign. With only Sharpe and Babcock left as analytical staff, they now had to rely on talented and perceptive scouts such as Knight to conduct interrogations. The other members of the bureau who corroborated Knight’s assessment could only have been Babcock since there was no one else available.

Right after the horrendous fighting at Spotsylvania, Sharpe found time to write to the Kingston Journal of the casualties suffered by the 120th NY as well as a breathless account of the fighting.

A partial culmination was reached yesterday in the capture of over 3,000 prisoners and 19 guns; making the whole number of prisoners sent to the rear so far 7,800. Extravagant reports are in circulation, but the above figures will be more than borne out by the official returns. This morning General Lee was found to have retired from our front, only to occupy a very strong position a few miles father on. Large numbers of his wounded are now being brought in by our stretcher-bearers, while piles of his dead encumber our front.

He then addressed the unique nature of the continuous fighting since the battle of the Wilderness. No longer were there brief individual battles between long periods of inaction or maneuver. He was identifying the first occurrence of that hallmark of the modern wars of the Industrial Revolution—continuous operations without let up.

I must leave you to form an idea from the army correspondents, loose and inaccurate as they are, of the series of operations which have attended us since crossing the Rapidan on the morning of the 4th instant. The situation, I believe, is unparalleled in history. Two large armies, substantially representing the fighting forces of immense populations, lying for nine consecutive days in each other’s presence, and throughout that time continually fighting each other with a determination evinced only at rare intervals by great nations in the crisis of their fate. No result is yet reached, and as I write, cannon and musketry have again opened.

He appended a list of the all the regiment’s dead (5), wounded (48), and missing (8). “We hope, but only that, that the heaviest is over. God grant that our own regiment, singularly brave among the foremost, may have offered its last tribute to the work!”51

As Grant prepared to attack the Mule Shoe, Sharpe dispatched his scouts to scour the area of operations. One group rode east from the army’s left in the direction of Guiney’s Station supported by a detachment of the 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry and came upon the plantation of a Dr. Boulware which was a collection point for Confederate taxes in kind. While enjoying a square meal, gladly prepared by the plantation’s slaves, the scout leader noticed a nearby Confederate signal station in operation about a mile away on the other side of the Mattapomy River. He dispatched the news to Sharpe immediately and requested a signal officer to read the traffic. The signal officer came and harvested a wealth of information. The scouts thought they had found a comfortable billet for the time being and suggested the signal officer relay what an important vantage point it was. His glowing reports, animated by his own fine meal, to headquarters resulted in orders for them to stay where they were and await further orders.

In the meantime the scouts were using their initiative to the best advantage. Scouts Knight, Cole, and Plew spotted a train from Richmond on the way to Guiney’s Station. The slaves pointed out it was the mail train. With the help of the 13th Pennsylvania, the scouts tried to capture the train, but it got away. They did capture the mail which had been dropped off. Among the personal letters was one from the “flying artillery” attached to Stuart’s cavalry.

If the writer had tried to give Gen. Grant the information of what Sheridan had done, and what success he had, it would have been impossible for him to have done any better. He told the young lady the day and date where they had met the Yankees, and how they had got whipped; how his battery was lost, all owing to the cowardice of their cavalry, and wound up by advising her never to marry a cavalryman.52

For Grant the knowledge of what Sheridan had been up to was his first information since the Cavalry Corps commander had disappeared behind Confederate lines on his deep raid. Knight’s report of his raid alerted Sharpe to the fact that Guiney’s Station was a supply depot as well as a telegraph station. It now had a guard force after Knight absconded with the mail. On the 18th, a larger raid by 300 cavalrymen led by the scouts drove off the guards, “captured telegraph operators and apparatus, rebel mail, etc. The station was destroyed, besides a large quantity of supplies.” Secretary of War Stanton was impressed enough to give it out as a press release, attributing the raid to the scouts.53

Grant was plainly impressed when Sharpe presented this intelligence and asked him how many scouts there were that got this information. When Sharpe replied that this particular find was due to the initiative to only a few men, Grant remarked that “he never had any information while he was in the West that would compare with what he had” been receiving on this campaign from Sharpe’s organization.54

The acquisition of papers through the picket lines also showed that Lee’s orders forbidding the pickets to communicate with their Union opposites was simply not being obeyed. For that matter, similar orders of General Meade for the pickets to have no communications from the enemy was more honored in the breach. Meade knew the value of the newspapers Sharpe was bringing him and surely granted him exception for their collection as well as the information on order-of-battle gleaned from casual conversation with Confederate pickets.55

Knight was harvesting mail from the Confederate flanks and rear. He rode into one village directly to the post office.

“No one was in at the time. I made a clean sweep of all newspapers and letters but touched nothing else.” Just as he was about to leave a woman walked in from the back room and said with genuine astonishment, “Mister, what are you doing?”

“Helping to sort your mail.”

“You will assort yourself into jail if you are not careful.”

“I reckon not. At all events, I’ll risk it.”

The scouts had to deal with frequent contact with the elite 9th Virginia Cavalry who were also roaming the flanks and skirmishing with any Union force they met. After capturing a large group of footsore infantry stragglers on the Union right flank at Spotsylvania, who thought the scouts were in larger number than they actually were, a man exclaimed, “‘Well, if I have got to be a prisoner I know of no body of men on God’s earth I would sooner be a prisoner of then you all.’ He had recognized Cline, Plew, and Cole. He been captured by our party the year before in the Gettysburg Campaign.”56

While his scouts were constantly probing the flanks and rear of the enemy, Sharpe and Babcock were not only keeping track of the enemy’s order-of-battle, but providing actionable intelligence for combat operations.

Sharpe had seen the importance of the crossroads at Corbin’s Bridge over the Po River behind the Confederate right flank and had sent Knight there repeatedly to observe the enemy during the Wilderness fighting. On the 7th his waiting paid off as he observed a Confederate cavalry regiment come up the bridge to act as a blocking force. At the same time, he witnessed the evacuation of Confederate field hospitals toward Spotsylvania Court House to the southeast followed by the cavalry. A friendly slave delivered to him a good map of the area dropped by a Union topographical engineer from which Knight was able to ascertain the direction of the Confederate movement. The slave told him also that the few men left on the other side of the river were cavalry and would pull out at night.

Knight had been a witness to Lee’s reaction to Grant’s decision to sidestep the Army of Northern Virginia and steal a march to Spotsylvania Court House which would put him behind Lee’s right and between Lee and Richmond. Grant had dispatched his trains first earlier in the day, and it was this movement that the local inhabitants had reported to Lee. Lee, in turn, instantly saw what Grant intended and reacted quickly to steal that march from Grant. He set his army in motion to get the Court House first. It was this movement that Knight observed.

While Grant and Meade assumed the movement of the trains would be too obvious to go undetected by Lee, they were confident that they still had enough of a head start to reach the Court House first. Warren’s and Sedgwick’s Corps were in the lead, with Hancock left behind to hold the right flank. A few miles to the south across the Po River, the Army of Northern Virginia was streaming toward the Court House. Knight arrived at the BMI camp after dark and was immediately summoned to army headquarters. He stated, “Our reports were always made to Col. Geo. H. Sharpe in person, if he was present.” Entering Sharpe’s tent he found only Babcock, who asked him how things were going on the Confederate right. Knight replied that “there was nothing going on except that they were evacuating and moving off to our left.” Babcock was stunned and immediately began to write out the scout’s report—“Knight reports the enemy leaving their left.” Then he turned to Knight and said, “This is one of the most important reports we have received in the campaign, and it is in direct conflict with reports received all day from officers along the lines. They report the enemy massing on our right, and the II Corps has been sent out there.”

Knight replied, “Yes, I met them as I came in, and there is no use of their going, for I tell you the last one of them [the enemy] have left there before this.” Babcock then closely debriefed him. “Then by a series of cross-questions as to what made me think as I did, he learned everything I had to tell. I showed him the map the contraband had given me—in fact left it with him, and fully committed myself to the report.” It was a nervous Knight who wandered back to the scout camp.

After leaving him I began wishing that I had not been quite as positive. I thought to myself, “Suppose these people fully realized what your presence there meant, and took that way of deceiving you. If they had troops where you could not see them, and should make an attack out there tonight, what will be thought of you.” To make the thing short, I will state that no sleep visited my eyes that night.57

What Knight had reported seemed to confirm Sharpe’s report of 8:00 a.m. that morning.

Twenty prisoners brought in this a. m. were taken partly on the enemy’s skirmish line but mostly in its rear, asleep in houses. They only know that their line has fallen back; don’t know where. Their rations were out last night and were to have been issued last evening; but neither to those who were on the skirmish line nor to those who were with or near the main body of the troops were any rations issued. The prisoners represent four divisions: Anderson’s, Rhode’s, Early’s, and Wilcox’s.58

These four divisions represented both Confederate corps on the field (Anderson and Wilcox’s III Corps, and Rodes and Early’s II Corps).

Within minutes of receiving this report, Meade sent it to Grant by the hand of his own son and aide, Capt. George Meade. Grant replied at 8:40 a.m. “I do not infer the enemy are making a stand, but simply covering a retreat, which must necessarily have been slow with such roads and so dark a night as they had last night. I think it advisable to push with at least three good divisions to see beyond doubt what they are doing.”59

The results of Knight’s reconnaissance were included in the following report submitted by Sharpe at 6 p.m. that night to General Meade:

GENERAL: Knight reports he left Tinder’s Mill on Po River 1 ½ miles Corbin’s Bridge at 3 p. m. Saw a small squad of rebel cavalry (15 men) on this side of the river at the mill. They recrossed on seeing our party. On other side of the Po, one-half mile below mill, on a large clearing, were 75 to 100 cavalry horses grazing. No indications of other force. Not as much rebel cavalry up that way to-day as yesterday. Our men went 2 miles beyond, some of our cavalry picketing in that direction, and saw nothing except as above.60

On the same day Cline reported on his reconnaissance of the army’s left:

I have followed the line of troops at Anderson’s plantation. Came on to rebel cavalry 2 ½ miles from Massaponax Creek. It consisted of two regiments. There is nothing at Hamilton’s Crossing; the iron is all taken up from Fredericksburg to Hamilton’s. The bed of the road is good except in places where it has been converted into rifle-pits. The bridge across the creek at this place is burned. I shall graze my horses and try what I can find to-night.

Anderson’s plantation was 2 miles north of the Spotsylvania and directly behind Union lines. From there northeast to the Massaponax was another 3 ½ miles, and from the creek to Hamilton’s crossing 4 ½ miles. The crossing itself was 4 miles south of Fredericksburg on the RF&P Railroad. The two cavalry regiments were what would be expected of Lee covering an open flank. That flank was wide open.61

That report also would have found a very receptive audience in Grant, who was intensely frustrated enough to telegraph Halleck that “The enemy are obstinate and seemed to have found the last ditch.” That very night, the Army of the Potomac was sent in motion to the left as Grant wrote:

I was afraid that Lee might be moving out, and I did not want him to go without my knowing it. The indications were that he was moving, but it was found that he was only taking his new position back from the salient that had been captured…

The night of the 13th Warren and Wright were moved by the rear to the left of Burnside. The night was very dark and it rained heavily, the roads were so bad that the troops had to cut trees and corduroy the road a part of the way, to get through. It was midnight before they got to the point where they were to halt, and daylight before the troops could be organized to advance to their position in line. They gained their position in line, however without any fighting… This brought our line east of the Court House and running north and south facing west.62

As much as Knight believed his report had been the cause of Grant’s deciding to move the army to the left, the special order putting the army into motion was dated at 5:45 p.m., but Sharpe’s summary of his scouting report was dated at 6:00 p.m. If anything, it was Sharpe’s report of that morning that may have made Grant apprehensive that Lee was beginning to move, as he indicated in his memoirs, as well as the cause of dispatching Knight for a special reconnaissance. Knight’s report then would have both confirmed Sharpe’s original observation and confirmed Grant that he had made the right decision. An alternative explanation based on Knight’s description of Babcock’s surprise was that his information was briefed orally by Babcock or Sharpe with the latter’s written account completed later.

Spotsylvania, May 13, 1864. (After Karamales)

Grant as usual never made a direct reference to Sharpe, the BMI, and intelligence operations. His references were oblique as in this case when he said, “I was afraid that the enemy was moving out.” From Sharpe’s report on Knight’s observations made at 6 p.m. Grant and Meade would have known they were in a faster race than they realized with a general as swift as fleet-footed Achilles. It gives some credence to Knight’s belief written some 30 years later that he had something to do with that.63

In any event, the attempt to outflank Lee failed again, and the armies settled down to glare and skirmish with each other for another week. Lee ordered every brigade to thoroughly scout its front. On the night of May 16 a scout of the 1st South Carolina, Sgt. Berry Benson, attempted to pass through the Union pickets by declaring himself a Union scout, relying on the dark to hide the gray of his uniform. It was a daring ruse, but the light of a candle made him a prisoner. He was taken first to an interrogation the next day at the headquarters of the provost marshal general on the very spot he had infiltrated only six days before. Patrick would have been mortified had he known. He was next taken to army headquarters where he was interrogated by a colonel that could only be Sharpe. Benson’s postwar account is the only one known to describe one of Sharpe’s interrogations from the prisoner’s point of view, although some 20 or more years after the fact. Benson was no ordinary prisoner, but a man whose success was due to daring and wits. He would prove no easy subject for Sharpe’s probing. Unfortunately, there is no surviving record of Benson’s interrogation to balance his memory of it.

Sharpe had already read Benson’s diary before he walked out of a tent and immediately accused Benson of being a spy. Benson asked him “what grounds he had for making such a charge, which I denied.” Sharpe had to be aware by this point how easily Confederate scouts had penetrated army lines, which explains his further line of questioning.

Sharpe then produced Benson’s diary and asked him if it was his and was this his writing. Benson confirmed both questions. Sharpe then asked, “Are you detached from your regular company?” Benson again said yes. “As what?” Sharpe asked.

“In a corps of Sharpshooters, sir.”

“Are these Sharpshooters mounted?”

“Not as a general thing, sir. A few have horses that they use sometimes in scouting. I have one, now in charge of my quartermaster.”

Sharpe then showed Benson a strip of paper and demanded to know what it meant. It was a receipt for a rebel prisoner dated the 10th. Benson explained that it was the receipt for him from the Union pickets. But, Sharpe, retorted, he was captured on the 16th. Clutching at straws, Benson said the 0 was actually a badly written 6, which Sharpe did not entirely accept.

Then Sharpe asked, “What were you doing when captured?”

“Scouting, sir.”

“For what purpose?”

“I was ordered to learn whether you were moving, sir.” This was a truthful answer which Benson felt could do no harm to the Confederacy.

“Then, upon being hailed, why did you claim to be a Union scout?”

“I hoped, sir, that they would not order me in, but would let me remain outside the picket lines.” Here Benson was dissembling. He had fully intended to penetrate the camp and had already done so on the 11th.

“But upon being brought in you represented yourself to Colonel Switzer also as Union scout.” It was Sweitzer’s pickets who had picked him up, and their colonel, despite the darkness, had recognized him by his accent as a son of the Palmetto state where he had once worked. Sharpe had obviously already spoken to him about Benson.

“True, sir. But I had to be consistent. I hoped there was a chance he might let me go.”

Sharpe thought for a moment and then said, “Inside a Federal camp, you misrepresented yourself as a Union scout. Is that not spying?” This was a gambit to frighten Benson.

Benson protested. “Colonel, I was taken outside your lines, armed with my regular arms, dressed in full grey uniform, as a Confederate. Was it wrong of me to make use of this accidental advantage? Wouldn’t your scouts have done the same thing?” Sharpe may have had trouble keeping a straight face since his scouts did exactly the same thing—Cline, Knight, and Anson Carney among the most brazen and cool.

Benson recalled that he had never been more eloquent in his life and that his interrogator seemed to soften to him. Sharpe said that Benson would probably be tried by court-martial as a spy. He said he felt kindly to Benson, would do all he could for him, and hoped things would turn out well. The scout, now in a state of high anxiety, was placed with other prisoners, one of whom told him that in his interrogation he had been asked what motive Benson could have had for claiming to be a scout. The man claimed he was just a frightened greenhorn. He gathered from the conversation of his interrogators that Benson would be classified only as a prisoner of war.64

All along the gory trail from the Rappahannock to the James, Grant had been expecting the imminent collapse of Lee’s army. Smelling blood he had kept attacking, turning the Overland Campaign into the most costly period of the war, willing to lose two men for every one of Lee’s. His expectations were fed by his experience against the Confederate armies in the west and by an uncritical assessment of information from prisoner interrogations that painted a picture of despair and breakdown. His picture at times verged on wishful thinking, as he continually confused Southern tenacity with the last surge of effort before the death rattle. He pointed out that Lee’s refusal to meet him in the open field since the Wilderness and fight only from behind entrenchments showed a collapsing morale. He did not stop to consider that the defense was a common-sense tactic by Lee who was fighting outnumbered and out-resourced and that in the hands of a brilliant engineer like Lee, the defense evened the odds considerably. Grant confused this with how the Confederates in the west had behaved, and to him it bespoke a loss of fighting spirit, a recognition of looming defeat. Lee’s men would be no different, he believed. Meade, with his long familiarity with Lee and his army, would write home in despair, “Virginia and Lee’s army is not Tennessee and Bragg’s army.” He realized that for Grant, the wish had become father to the thought.65

It is difficult to imagine Sharpe and Babcock, with their seasoned interrogation skills, giving undue weight to the tales of woe from deserters and prisoners. That’s what prisoners often do to curry favor with their captors. But even these reports were far thinner on the ground than would be imagined from Grant’s enthusiasm. On May 17 Sharpe reported the results of an interrogation of one deserter.

We have a deserter who came into our lines last night from Forty-fifth North Carolina, Daniel’s brigade, Rodes’ division, which he left lying on the enemy’s left near where Hancock charged the corner. Thinks his whole division is there. Loss in his brigade very heavy. General Daniel killed. This man thinks that within a few days the spirit of the men has somewhat failed. Rations issued for two days Saturday night, which is the last he was in the way of knowing about. Knows nothing of re-enforcements or communications.66

Grant received these reports through channels from Meade and did not have the opportunity to be briefed personally by Sharpe or Babcock. He appears to have read what he wanted into them. On May 23 on the North Anna he would write Halleck, “Lee’s army is really whipped. The prisoners we now take show it.”67

By the last week of May, Sharpe was able to inform Meade and Grant that Lee had been receiving important reinforcements. On May 24 his scouts had identified Kemper’s Brigade of Pickett’s Division as the force opposing Hancock the day before and reported that civilians had said that the rest of the division had arrived at the Chesterfield Station just north of Hanover Junction on the RF&P Railroad. That brigade earlier had been detached to serve under Maj. Gen. Robert F. Hoke in the capture of Plymouth, North Carolina, in April. Scouts now reported as well that 2,000 men passed through Milford, barely 10 miles south of Spotsylvania, on the 20th. He added:

[W]e have a prisoner from Forty-third North Carolina, which has been with Hoke in North Carolina and is now back with three other regiments (Twenty-first North Carolina, Fifty-seventh North Carolina, and the Twenty-first Georgia), having left Richmond day before yesterday early, marched from Milford toward Lee’s army and back again yesterday. This man says three trains left Richmond with the troops, and he heard Ransom’s brigade was on the way…

Barton’s Brigade of Pickett’s Division had also marched through Milford about this time to Spotsylvania but, finding the army falling back, marched to Hanover Court House where the rest of the division assembled and was joined by Pickett himself on the 27th.

Sharpe was faced with one of the most difficult problems for an intelligence officer—to make sense of an enemy’s order-of-battle that was in the immediate process of both heavy reinforcement and significant reorganization. The following explanation keyed to the previous report presents the scope of the problem.

Sharpe was correct that the 43rd North Carolina had been indeed with Hoke at Salem as one of the regiments in his original brigade. The 21st North Carolina and 21st Georgia were also part of Hoke’s original brigade and fought at Drewry’s Bluff in the defense of Richmond against Butler’s army. Once transferred to the Army of Northern Virginia, they were assigned to three brigades of Early’s II Corps: The 43rd North Carolina went to Grime’s Brigade and the 21st Georgia went to Dole’s Brigade, both in Rodes’s Division; the 21st and 57th North Carolina went to Lewis’s Brigade, Ramseur’s Division. The 57th had originally belonged to Lewis’s Brigade before being sent to North Carolina, and was the only one that would have fit into Sharpe’s order-of-battle records.

In April Hoke had been promoted to major general after his victory at Plymouth in command of an ad hoc division. To complicate things for Sharpe that was not the division with which he joined Lee. It had been cobbled together from four brigades that had originally been stationed along the coast but recently transferred to Richmond. In early May Hoke now commanded a division in the defenses of Richmond. It helped repulse Butler on May 16 and was ordered to join Lee but dropped two of its brigades and picked up two new ones from two other divisions in Richmond. The division joined the Army of Northern Virginia on May 18, about the same time as Pickett’s Division began arriving. Hoke’s Division’s returns for May 21 showed 7,125 men present for duty. The records do not indicate whether Sharpe knew the composition or the strength of the division. He would have seen Hancock’s report of the 21st in which slaves reported that Hoke’s Division with 10–13,000 men had arrived at Milford 2 miles south of Bowling Green to reinforce Lee. Given the source, Sharpe would have discounted the number but not necessarily the unit.

In the same report of the 22nd, Sharpe also cited the dispatches captured by Cline that gave information on Sheridan’s Cavalry Corps raid and the enemy’s movements directed at the Union army. They also brought in Richmond newspapers with more information on Sheridan’s approach to the capital. That report had one more useful piece of information.

A prisoner from Longstreet’s Corps described with a certain rough accuracy the shape of the positions occupied by Lee’s army on the North Anna. It was in the shape of a V. Hill’s Corps ran between the North and South Anna Rivers then curved up to run along the North Anna until it joined Longstreet’s Corps, which ran diagonally southeast of the river where it joined Ewell’s Corps. The genius of this position was that the rounded apex of the V shape rested upon the river. Reinforcements then could be easily shifted within this triangle and just as importantly it ensured that the enemy would have to divide his forces in order to attack both long sides of the V. Warren’s Corps arrived on the 23rd and crossed the river, only to run into a strong attack from Hill. Hancock arrived later and took a bridgehead over the river as Anderson pulled his I Corps back. Sheridan returned with the Cavalry Corps on the 24th. While Grant was staring at the Confederate position across the river, Lee was prostrate with diarrhea, Hill was sick, and Ewell exhausted, none of which was known on the enemy side. Again as at the Wilderness, the absence of BMI reporting tells us nothing about the intelligence support of the Union operation.

On the 26th Sharpe’s scouts also brought in the information that with the arrival of troops from the Valley and the opinion of civilians, no Confederate forces had been left in the Valley. This was undoubtedly Gen. John C. Breckinridge, former vice-president of the United States under John Buchanan (1857–61) and Lincoln’s opponent for the presidency in 1860 and now fresh from his victory at New Market in the Valley on May 15. Sharpe believed he was there personally. The day before Grant wired Halleck based on Sharpe’s reporting that “Breckinridge is unquestionably here. Sixty-six officers and men have been captured who were with Hoke in the capture of Plymouth.”68

Sharpe confirmed that Breckinridge’s Division had joined Lee’s army. A deserter from the 23rd Virginia Battalion, Echols’s Brigade, had left his camp at Hanover Court House right after they arrived on the 24th. He identified the division’s two infantry brigades correctly but mistakenly included Imboden’s Brigade of cavalry with it. In the same report he described prisoner testimony of trains leaving Richmond filled with furloughed men returning to their regiments in Lee’s army. There were, however, no organized units, only individuals. Sharpe also reported the position of Lee’s right flank held by Ewell’s Corps.

Sharpe would have a lot to do to keep track of all the organizational and command changes in the Army of Northern Virginia caused by heavy casualties to include division and brigade commanders. Normally, this was the work of months to untangle all these changes in a stable base. The BMI had neither the time nor the base. The army had been on the march between the Wilderness and Spotsylvania for two days (May 7–8), between Spotsylvania and the North Anna for four days (May 20–23), and between the North Anna and Cold Harbor for five days (night of the 26th to the first of June)—a total of 11 of the 28 days since the campaign began on May 4 to the army’s arrival at Cold Harbor, or almost 40 percent of the time. It is amazing that the BMI accomplished as much as it did. Brigadier General Patrick emphasized this same problem when he prepared a prisoner-of-war summary for Grant at the beginning of November after the armies had settled around Petersburg. “It is impossible to tell with any degree of definiteness, on what occasions the captures were made… In consequence of the manner in which we moved, no permanent record of the prisoners taken was kept, until after the 27th of July, when the office at this place [City Point] was established.”69

Johnson’s Division of II Corps had disappeared from the order-of-battle, its remnants consolidated into a single brigade after the carnage at the Salient. Two new divisions, those of Breckinridge and the other entirely new division under recently promoted Maj. Gen. Robert F. Hoke, were added to the army but not subordinated to any of the corps but under Lee’s direct control. Pickett’s Division, which had been detached since last September, rejoined I Corps as well. Sharpe would have a lot to do to keep track of all the organizational and command changes in the Army of Northern Virginia. Wilderness and Spotsylvania had reaped a heavy harvest of Lee’s regimental, brigade, and division commanders.70

Not counting the individuals returning from furlough, Sharpe had informed his commanders that Lee had received in the space of less than a week reinforcement in three new divisions and a number of separate regiments, and that the defenses of Richmond and the Valley had been stripped to provide them. However, the flow of reinforcements did not even begin to make up for the losses of the Army of Northern Virginia. On May 31 Lee issued the following order:

... to get every available man in the ranks by to-morrow. Gather in all stragglers and men absent without proper authority. Send to the field hospitals and have every man capable of performing the duties of a soldier returned to his command. Send back your inspectors with instructions to see that the wishes of the general commanding are carried out. Let every man fit for duty be present.71

By the time the army was moving to Cold Harbor, Grant had cut loose from his overland communications. While the army was self-sufficient for the near term in everything it needed, it had become more than difficult to communicate with Washington in a timely manner, especially since the 9th Virginia Cavalry carefully patrolled the areas to the army’s rear and snatched up any small parties they came upon. Sharpe’s scouts were now entrusted with dispatches. Anson Carney and another scout tried to go by land through the Wilderness but had to turn back.

Cline and Phelps made their way to the Potomac River, constructed a raft and got across to the Maryland side, where the river was several miles in width; got aboard a schooner where they had smallpox. They had to draw their pistols and threaten to use them before they could make the crew get underway.72

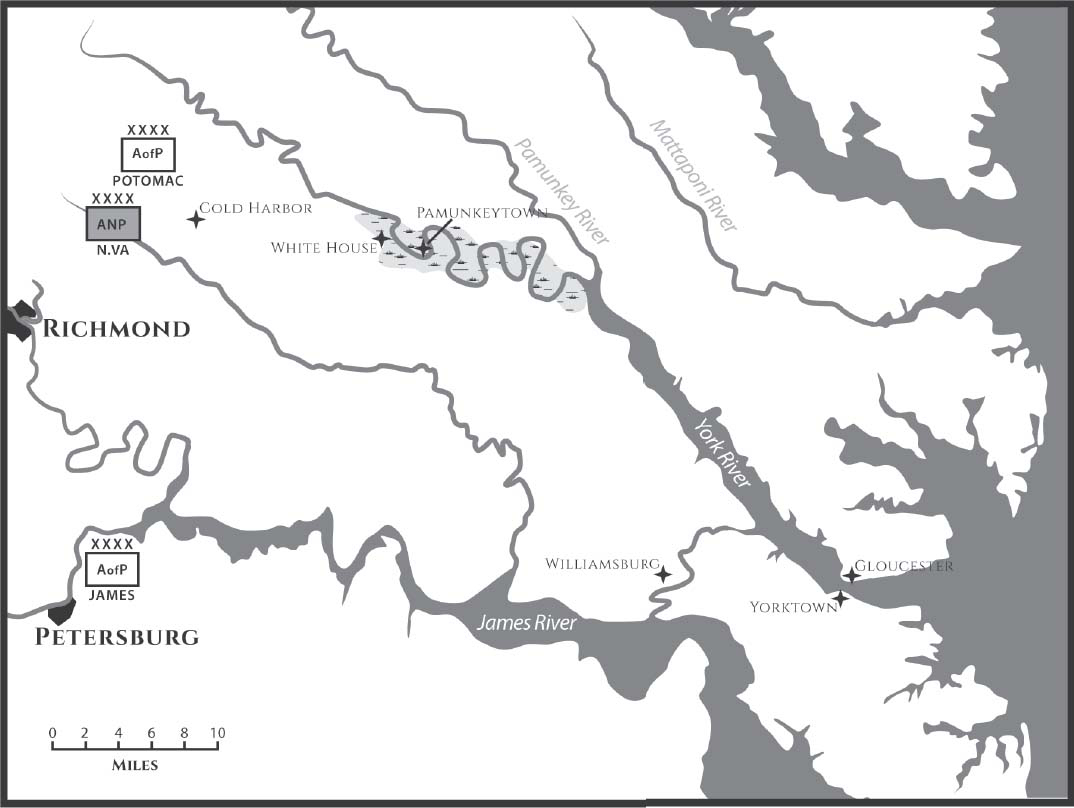

At the end of May after the army had crossed the Pamunkey River, Knight was told to report to the command group. Patrick told him that Assistant Secretary of the Army Charles Dana, who had accompanied Grant’s headquarters since Wilderness, wanted to see him. When he reported to the command tent, Grant and Col. Rufus Ingalls, the quartermaster general of the army, were there too. Dana introduced himself and said, “You are a scout. We want to send dispatches to Yorktown. That is the nearest point we can reach a telegraph.” Knight thought to himself that “Yorktown was about 70 miles away, and the country between in full possession of the enemy. I am free to confess that there was no craving on my part for the job.” All he knew of the area to be crossed was what he remembered as an infantryman in the Peninsular Campaign.

Two years had elapsed since. I thought over our guides, and the different scouts; not a man of them knew a thing of the country, and told Mr. Dana that were was not a horse in our party in fit condition to make such a trip, and said my own horse had a sore back—in fact, they all had. Gen. Grant, I could see, was listening to our conversation. When I mentioned the condition of the horses in our party, he said: “Ingalls, haven’t you got fresh horses in the corral?” “Yes,” said he. Then he said to me: “When you get through here, I will go with you to the corral, and show you what I have.” That settled it, and I could see there was no way to get out of it, and might as well put on a cheerful air as any other. Mr. Dana then showed me a lot of dispatches, and marked them, saying, “This is to be telegraphed, and this is to be mailed,” until he had all but three marked.

Now well-mounted and with trusted companion James Hatton he set out. They encountered Brig. Gen. George Custer, who remembered Knight from their service with Brigadier General Kearny two years before and inquired of their mission. When told, he replied, “I should not care to take such a trip.” Custer was more than right. That very day a Pamunkey Indian warned them of heavy Confederate patrols. Before long they were seen and chased but escaped. Hiding out that night, they held their horses in silence in the woods as the patrol stopped within earshot to discuss their escape, sure they were couriers. That decided Knight that the job was only for one man on foot, and he sent Hatton back with the horses. The next day he was chased into a swamp by the enemy and hid all day.73

Judson Knight’s Adventure Down the Pamunkey River. (After Karamales)

The following day he made his way to the Pamunkey River and encountered several slaves fishing. He tried to pass himself off as a Confederate soldier with the group that had just tried to catch him. A slave told him outright that he was a Yankee:

“Oh, you don’t talk like our folks does.”

Up to that time I had imagined I was playing the part of a Confederate rather successfully, and to be detected by this fellow so easily made me ashamed. I had played the part of a Confederate surgeon only the previous Winter, and knew that there was no suspicion on the part of several families of white people of my being anything than what I represented myself to be. It lowered me several pegs in my own estimation.

They asked him if was true that Yankees cut off the arms of black people as their masters had told him. He replied that it was nonsense, and they were immensely relieved, fed him, and sold him a boat.

He paddled down the river and eventually climbed a bluff to make his way inland to White House, when he was stopped by Union pickets who escorted him to Major General Smith, commanding XVIII Corps. The general put him on the first steamer and sent him to Yorktown where he delivered his dispatches to the telegraph and post offices. It had taken him two days. He treated himself to a good meal and new clothes and regaled the troops there with stories of the fighting. He made his way back to army headquarters on foot and horse, arriving on June 2, the day before grand assault at Cold Harbor.74

Even Grant considered Lee’s position on the North Anna too dangerous to attack, and on the night of the 26th the army once more moved out to its left, crossing the Pamunkey River marching southeast to wrap around Lee’s right flank. Meade sent Sheridan ahead with cavalry divisions to take the crossroads village of Cold Harbor. Lee quickly joined the race but found the cavalry there first on June 1. Anderson’s Corps attacked with force but recoiled at the firepower of the repeater-armed Union cavalry. The Confederates drew back and immediately set about building their field fortifications. An attack late in the day by Union infantry nearly cracked the Confederate line; Grant planned for the killer stroke to be delivered two days later. There is an absence of BMI reporting from May 29 until right after the assault, so there is little to base what intelligence support Sharpe could have provided. Whatever the loss of documentation, it appears that the senior officers were pleased with what they were getting from the BMI.

On June 2 a Union signal station reported that the enemy’s positions had remained unchanged, and Sheridan’s cavalry was hovering on the Confederate flanks. There was little more that Sharpe could have added that would have prevented the horrendous loss of 7,000 men to Lee’s 1,500. Grant ordered a second attack, but the army from private to general simply refused. Grant would later write that his decision to attack was what he regretted most in the war. In a speech Sharpe gave after the war in 1876, however, he stated, “The general commanding always maintained that we should have continued the contest even at a further loss of thousands, and if we had only known, as we know now, that their Army was practically destitute of ammunition when we withdrew, how much subsequent slaughter and expense would have been saved.” Unfortunately, the exhaustion of Confederate ammunition was not something the BMI was able to uncover at the time.75

The evening after the attack, Sharpe made a report based on a pool of about 300 prisoners taken that day. “Their examination shows that to-day Ewell held their left, Longstreet next, Breckinridge next, with a new division of four brigades on their right, and that the greater part of A. P. Hill’s corps was in reserve near the right.” He was precisely correct in every detail except he had not yet learned that Ewell had been replaced by Early.76

The day after the last attack, Sharpe had a fruitful opportunity to glean information through the picket line. Lieutenant Colonel Lyman was an observer as he came over to the Confederate side to seek a truce in order to pick up the wounded who lay thick on the line. “The pickets were determined to have also a truce, for when a Reb officer went down the line to give some order, he returned quite aghast, and said the two lines were together, amiably conversing. He ordered them to their posts, but I doubt if they staid.” Lyman was back on the 7th, when Lee finally granted the truth after most of the wounded were dead. Both sides came out onto the field now as burial parties.

Round one grave, where ten men were laid, there was a great crowd of both sides. The Rebels were anxious to know who would be next President. “Wall,” said one of our men, “I am in favor of Old Abe.” “He’s a damned Abolitionist!” promptly exclaimed a grey-back. Upon which our man hit his adversary between the eyes, and a general fisticuff ensued, only stopped by the officers rushing in.77

In all of this carnage, Sharpe and Knight still found time to help out a forlorn soldier. Knight remembered:

My old regiment (2nd NJ) went home from Cold Harbor, and a day or two afterward one of the guards at the “bull-pen,” a member of the 20th NY, came to me and said: “There is a man in the bull-pen who says he belongs to your old regiment, and wants to see you.”

I went back with him, when a young fellow who was on the inside of the line of guards pressed forward as far as the guard would let him, and said: “Don’t you know me, Sergeant?”

I took a good look at him, and answered: “No; I can’t say that I do.”

He said: “Sergeant, I used to belong to your old regiment.”

“What company were you in?”

“G, and yours was H.”

“Yes; that is right. So you were in Capt. Close’s Company. How did you get in here? The regiment has gone home, and I can’t see how you should be in the bull-pen.”

He then told me that he was in one of the Wilderness fights, and was wounded; had been sent to Washington to a hospital, and as soon as he could leave it applied to be sent to his regiment; had come down the Potomac to Port Royal, and had helped to guard a wagon-train from there to Army Headquarters; when he got there his regiment was gone. His story had not been believed, and he had been brought up in the pen. After listening to his story he said: “You remember me now, don’t you, Sergeant?”

I could not recollect him, and said so. Tears came into his eyes as I turned away and walked to Col. Sharpe’s tent, who at that time was Deputy Provost-Marshal-General of the Army of the Potomac. I went in and told the story to Sharpe, and when I got through he said: “Do you remember him?”

“Hardly; but I know he tells the truth.”

“Well, said he, “it is a shame, and we will have him out.”

He then wrote out an order to turn the boy over to me, and told me to go and get him. When he came the Colonel questioned him for a few minutes, gave him an order for transportation and the paper he would need to keep him out of trouble with military authorities, and turned him loose. He was one of the most grateful boys I ever saw.78

Even after the disastrous assault, Grant’s determination to fight it out with everything he had was clear to everyone. Writing his Uncle Jansen, Sharpe noted that Grant had ordered that no officer could go to Washington except the wounded. Sharpe was wistful since his wife was living in Washington solely because of its proximity to him, “and I must have her there as long as she desires it.”

But his attention was only briefly distracted. The bloodbath at Cold Harbor had left Sharpe with a sobering idea of what lay ahead:

I can scarcely say whether we shall push on to Richmond direct from this point or not. The Chickahominy is deadly—but it would probably cost us from 20 to 30,000 men to fight our way thus to the James—& we should be that much weaker on getting there, without perhaps being able to inflict equal loss on the enemy, as we have thus far done.

He then weighed the options. It was all speculation but informed speculation since Grant was keeping his plans close to the vest. “We are now 12 miles from Richmond by the roads—& in swinging around to the James, every step would put us farther off. The country around the James is more healthy—we would have good communications & the gunboats.”

While the next move hung in the balance, Sharpe’s faith in Grant was only growing. “You see it is difficult to decide—but Grant has decided I have no doubt. His determination is immense—& I begin to think him a considerable of a man.” Sharpe’s confidence had survived the huge casualties of the campaign so far; he could see the long-term effects on the enemy. “We have certainly not been whipped—we have whaled Lee considerably twice, without routing him, to be sure—and we have sent many guns, colors, & 12,000 prisoners to the rear. The Va Central [railroad] is destroyed & we are in front of Richmond.” Then in a bit of overconfidence he would have cause to rue, he wrote, “[I]f he [Lee] want now to go to Penn, I think Grant would hail the opportunity.”79

As chief of the BMI and deputy provost marshal, Sharpe’s writ ran to identifying and suppressing subversive activities and espionage among the local population in the army’s area of operations. He was appalled when an overzealous commander sent him two local women accused of providing information to the enemy:

They are ignorant and simple-minded people, and I have failed to discover the slightest evidence of any intent on their part. I think they had no idea that they were doing any harm, and that they would have given us information about the rebels with equal readiness had the occasion offered. Mrs. Bowles is very far gone with child, and General Patrick approves a respectful recommendation to the commanding general that they be returned home.80

That writ, however, ran rougher when the examination of seeming Confederate deserters indicated that they were after all originally Union deserters who were trying to escape service by claiming Lincoln’s amnesty. Patrick wrote about the method used to winnow out these characters:

The usual practice of this office in examining prisoners has been to let them tell their own stories until by their own falsehoods and impossible statements we know they are deserters when we tie them up to trees and keep them without food until they tell their regiments. Colonel Sharpe, Capt. Leslie and myself are the only persons who do this and among the vast numbers thus treated no mistake has ever been made.81

This and only one other piece of correspondence, to be shown later, so far discovered in the official records of the National Archives identifies what might be called in today’s more sensitive if not overwrought times “enhanced interrogation methods.” Surely, if such methods had been common, the Southern newspapers and literature, both during and after the war, would have been rife with graphic descriptions.

Although Meade forced Sharpe’s reporting to go through channels, it was being read and acknowledged at the highest levels. On June 9 at Cold Harbor, Assistant Secretary of War Dana wrote to Stanton, forwarding “a communication just send [sic sent] from Colonel Sharpe, deputy provost-marshal-general, to chief of staff, Army of the Potomac,” noting “Principle facts above are confirmed by various other evidence, and are most probably correct.” The reference to the authority of all-source confirmation is telling.82

Sharpe’s continuous acquisition of Richmond and other Southern newspapers allowed Grant to remain informed of the progress of other commands in a far more timely manner. By this point, he was largely cut off from overland communication with Union territory. Enough Southern forces filled in behind his armies made it dangerous, as Knight’s adventures on the Pamunkey showed, to try to get information this way. Southern newspapers, on the other hand, had the advantage of interior lines connected by telegraph and, over short distances, couriers. Rawlins would be sure to mention these finds in his letters to his wife. On June 7 he wrote he was reading a Richmond Inquirer of the same day, a feat of timely intelligence on Sharpe’s part. That issue related welcome news. Union Maj. Gen. David Hunter had defeated and killed General W. H. “Grumble” Jones at the battle of Piedmont 12 miles beyond Staunton. Rawlins described it as “a triumph which will inure greatly to our interest in this campaign.” He continued, “Hunter is doing what we expected Sigel to do some time since. Hunter and a heavy force, under General Crook, will meet now without doubt at Staunton if they have not already done so. Their combined forces will be sufficiently strong to enable them to strike a staggering blow to the Confederacy.”83

On June 10 Grant’s chief of staff, Maj. Gen. John Rawlins, wrote a letter in which he stated that Richmond newspapers brought Grant his first news of General Hunter’s continued progress and successes in the Valley, a full three days before Hunter’s dispatch arrived with the news. Grant had every right to be pleased with Sharpe and his men. He was now clearly getting detailed information from Sharpe on the state of Confederate logistics at the strategic level. That had concentrated his attention on Lynchburg, the nexus of two vital railroads and the James Canal. His orders to Hunter embodied that appreciation. Hunter was to seize Lynchburg and Charlottesville to ensure that the railroads and canals “should be destroyed beyond possibility of repair for weeks.”

Grant would write in his memoirs of the source of some of that information—the Richmond newspapers Sharpe’s scouts were bringing through the lines or acquired by trade from the pickets.

About this time word was received (through the Richmond papers of the 11th) that Crook and Averell had united and were moving east. This, with the news of Hunter’s successful engagement near Staunton, was no doubt known to Lee before it was to me. Then Sheridan leaving with two divisions of cavalry, looked indeed threatening, both to Lee’s communications and supplies. Much of his cavalry went after Sheridan, and Early with Ewell’s entire Corps sent to the Valley. Supplies were growing scarce in Richmond, and the sources from which to draw them were in our hands. People from outside began to pour into Richmond to help eat up the little on hand. Consternation reigned there.

Again on the 15th Rawlins wrote that Richmond papers reported Hunter’s capture of Lexington. On the 21st and 22nd he cited Richmond papers that announced the defeat of Hunter at Lynchburg on the 18th. This was the first news to reach Grant about an important Union setback in the effort to destroy a vital Confederate transportation hub. All of this information was courtesy of George Sharpe and his BMI.84

Toward the end of the Overland Campaign, Knight would encounter a refugee from Richmond whose information would lead to a great opportunity for the BMI in the months to come.

At Cold Harbor I met a citizen who was sent to our quarters with orders for us to take care of him. He was with us, I should think, three days, then he came over from Gen. Grant’s and Gen. Meade’s headquarters and said to me:

“Good-by; I am going to leave you.”

“Well, sir, good-by. Where are you going?”

“To Philadelphia.”

He then told me that Grant and Meade had not made him take the oath of allegiance; and when I asked him the reason, he said it was not expected from him, so that the Confederates should have no excuse, if they heard of it, for confiscating his property. Before I got through talking with him, I learned he was from Richmond; that his name was John N. Van Lew; that his family were from Philadelphia, originally; that his father had been a successful hardware merchant in Richmond for many years previous to the war; also, that he was in the same business; that his mother and sister were both living on Church Hill; that the family were known as Union people; also, that the rebel Provost-Marshal-General Winder was boarding at their house, and that they gave him his board as an equivalent for the protection he afforded the family. As soon as he told me he was from Richmond I began importuning him to join our party, and he inquired what we were. As soon as I told him he declined, saying that the life would not suit him.85

When we parted, he said to me: “I will tell you something that may be of value to you. If you can ever get into communication with my mother or sister, they are in a position where they might furnish you with valuable information. Their names are both Elizabeth Van Lew.” I walked with him several miles and urged him to stay with us, for patriotism if nothing else, but did not succeed.86

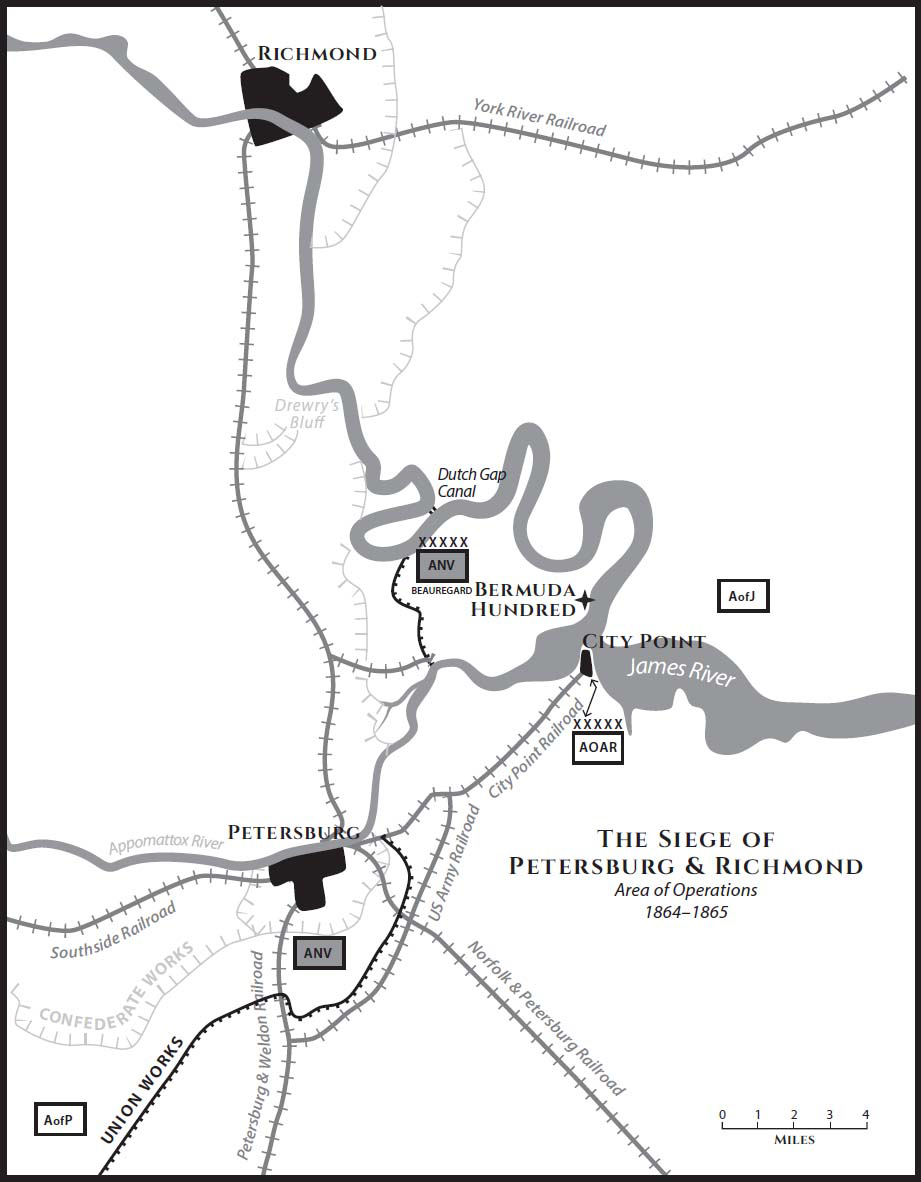

The Siege of Petersburg-Richmond Area of Operations 1864–65.