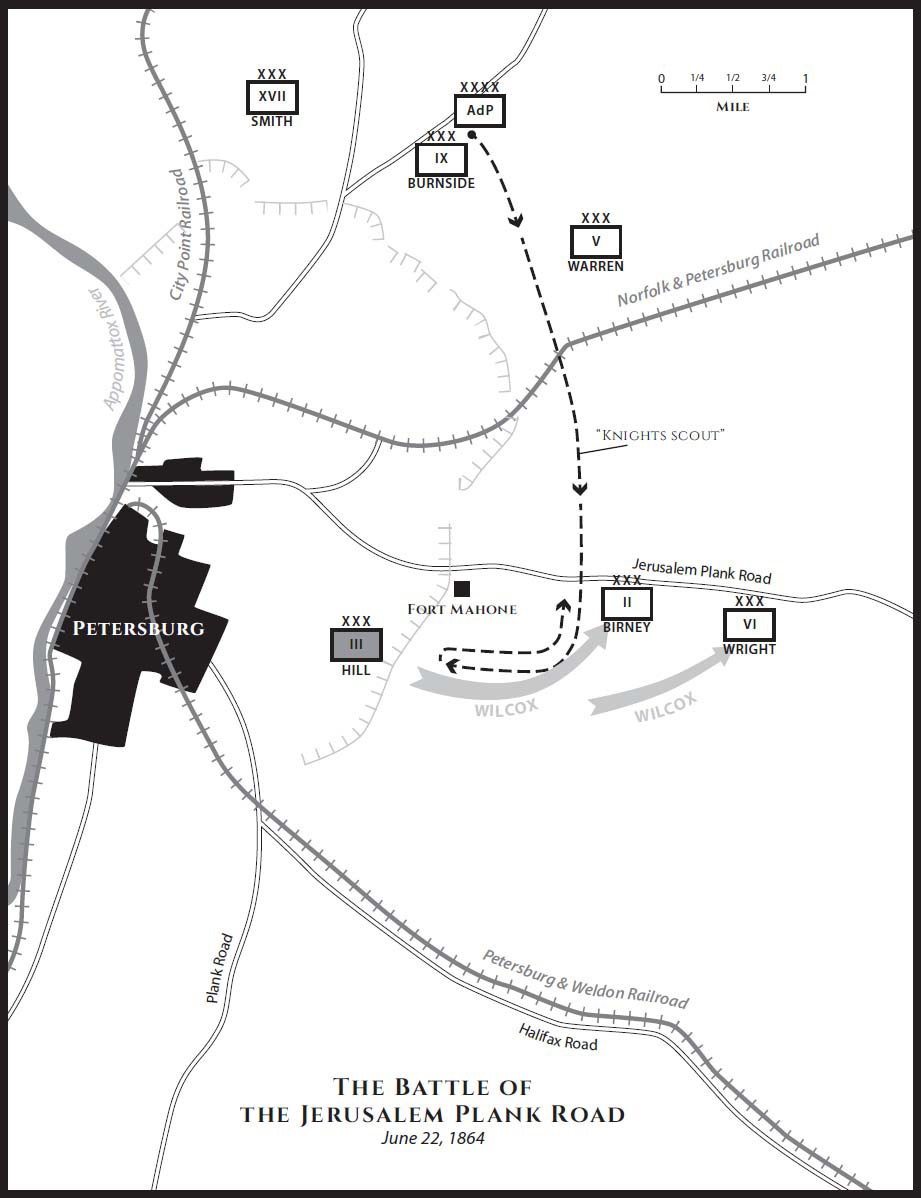

The Battle of Jerusalem Plank Road, June 22, 1864.

Blocked again by Lee north of Richmond and with dangerously extended supply lines, Grant sought to steal another march on the night of June 12. This time the army would cross first the Chickahominy then the James River below Richmond to seize Petersburg and cut off the Confederate capital’s communications and force Lee into decisive combat. His supply lines would then be reestablished by sea and the James River.

Sharpe had been reporting on the state of the garrison of Richmond and Petersburg. On June 10, the interrogation of North Carolinian deserters indicated that the “force for the protection of Richmond is altogether too small. It is not believed that their new troops and conscripts will make a good fight, and but few of the old troops are left.” The next day Sharpe reported that one of his scouts who had infiltrated an enemy headquarters had overheard Confederate Brigadier General Scales speaking to a number of officers:

... a large number of [Union] scouts are employed to continually approach and reconnoiter our lines in front, as it is their momentary expectation to find our lines withdrawn for the purpose of being passed to the left to the James River. For this, it is claimed, full preparation has been made, and it is given out in the rebel army that a portion of General Beauregard’s forces have occupied and intrenched [sic] Malvern Hill, and that their lines are sufficiently prolonged to connect with Malvern Hill from their present position in our front.1

This information could have had a chilling effect on the resolve of anyone but Grant. Instead it beckoned with opportunity. He had learned that sidestepping to his left to get around Lee’s flank in order to bring him to decisive battle simply was not working. Lee was just too good a soldier and engineer to let that work.

Grant worried that trying to maintain a line of supply for operations northeast of Richmond “would give us a long vulnerable line of road to protect, exhausting much of our strength to guard it,” while allowing the enemy to be supplied by the network of railroads south of the James. “I now find, after over thirty days of trial, the enemy deems it of the first importance to run no risks… They act purely on the defensive…” The enemy also had an enormous new advantage of position. “Lee’s position was now so near Richmond, and the intervening swamps of the Chickahominy so great an obstacle to the movement of troops in the face of an enemy… Without a greater sacrifice of human life than I am willing to make,” something else would have to be done to cut this Gordian knot. He concluded, “I determined to make my next left flank move carry the Army of the Potomac south of the James River.”2 His objective was Petersburg, just south of Richmond, where all the railroads that could supply Lee and sustain the Confederate capital converged.

Leaving Warren’s V Corps to demonstrate in front of Lee, Grant put the army in motion on the night of the 20th, a full 8 miles north to the rear. Security was so good that Lee was not to discover that his opponent had slipped away until the next day. Even then, Lee did not comprehend the audacity of the move. He thought Grant would attempt another, shallow envelopment that would directly threaten Richmond from the north or east. This he planned to forestall as he had the other such moves. The operating element of the intelligence obtained by Sharpe was that Lee would only put his move into action when his scouts had revealed another attempt to outflank him. To meet that threat Lee threw cavalry out initially to cover the line from Malvern Hill to White Oak Swamp Creek, a southern tributary of the Chickahominy. With one flank resting on Malvern Hill which itself frowned over the James River and the other flank on White Oak Swamp, he felt assured that he had a powerful defensive line of little over 5 miles’ length.

Sharpe’s report did contain a positive error—Beauregard had not garrisoned Malvern Hill with infantry. That hill had been held by McClellan’s men in the 1862 Peninsular Campaign against repeated bloody charges by Lee. It could serve such a purpose for the Confederates this time. Grant encouraged him to think defensively by aggressively screening this line with V Corps before Warren slipped off to join the rest of the army assembling on the north bank of the James. Brigadier General James H. Wilson’s Cavalry Division continued the screen on the 13th after Warren withdrew, which prevented Lee from discovering the massive movement of the Army of the Potomac about 8 miles to Wilson’s rear.

Lee was further inhibited from offensive action by his dispatch of II Corps, to save threatened Lynchburg in the Shenandoah, on the same day that Grant slipped away from him. He had a further mission to threaten Washington to force Grant to thin his forces to defend the capital. Lee’s security emphasis was on his own left to make sure that Grant did not learn he was sending Early off. It worked perfectly; no word leaked out. Grant and Lee had successfully deceived each other on the same day in what both thought would be a decisive strategic move. It was one of those very rare examples in military history in which both sides attempt the same maneuver simultaneously and in opposite directions. Both sides were so intent on their stratagems that they did not detect each other’s departure.

Grant cut loose his overland communications and ordered the army to be supplied up the James River with his base at City Point. In three days 115,000 troops in five corps and one cavalry division passed over a pontoon bridge thrown across the James River. At over 2,100 feet it was the largest ever built, and it was built in less than a day. The 49 batteries of artillery of almost 330 guns were accompanied by their 1,200 caissons and ammunition wagons and followed by an enormous supply wagon train that together stretched 35 miles long, and was trailed by 3,500 beef cattle. The transfer of the army had been a triumph of staff work and a superb performance by the quartermasters and engineers.3 “Grant had done the near-impossible and had completely out-witted Lee. The Federal movement had been complicated and dangerous, and had been handled with rare skill.”4

For Grant this maneuver was meant to be the killing stroke. He was showing the strain of this great movement so fraught with perils. He lit his cigars over and over, again and again, letting them go out. He was short with his staff officers, and his aide, Col. Horace Porter, wrote that he was “wrought up to an intensity of thought and action which he seldom displayed.” By seizing Petersburg, he would cut the three southern railroads that tied Richmond to the rest of the Confederacy. It would force Lee to abandon his endless entrenching to come to the rescue of the capital and logistics. It meant Lee would have to fight in the open where Grant’s numbers would be decisive. It should have been done. It could have been done. The Confederates had erected for the defense of Petersburg the strongest fortifications seen by the Union army in the war, yet there were barely 2,200 men to guard them.5

The Army of the Potomac had massed on the northern bank of the James behind the Wyanoke Peninsula by the 14th. Lee by now had sensed that Grant was somewhere on the James. Yankee stragglers stated Grant was heading for Harrison’s Landing where McClellan had had his base camp in the Peninsula Campaign of two years ago. McClellan’s fortifications were still intact, and Lee did not think it wise to attack Grant there. At the same time, Sharpe’s scouts were actively looking at Harrison’s Landing and reported back that it was guarded by a picket line with mounted infantry behind.6

The Army of the Potomac started to cross the next day. At the same time, Grant had ordered Butler to send Smith’s XVIII Corps with Maj. Gen. August V. Kautz’s cavalry in the lead. His cavalry overran the outer line of works in a great rush, but the infantry would be needed to take the more imposing lines behind. Smith and his corps reached it first on June 16—and stopped. The sheer might of the fortifications and the dread of the slaughter at Cold Harbor gave him pause that he must mount a deliberate attack as did the rumor that Lee’s troops were arriving on his front. Beauregard, in command of the defenses of Richmond and Petersburg, had stripped the latter of defenders to send reinforcements to Lee and recently to counter an attack by the Army of the James at Bermuda Hundred on the 10th, the very diversion that Grant had counted on when he ordered the attack. But Beauregard had just thrown the bumbling Benjamin Butler back into his works at Bermuda Hundred, something Grant had not planned on. Now Beauregard began shifting his meager forces south to Petersburg while begging Lee for help. While Smith contemplated his next move, Hancock’s II Corps, which was supposed to support the attack, was uselessly countermarching because of erroneous orders. Grant had not taken Meade into his confidence that Hancock was supposed to throw his weight into Smith’s attack, and this mission was not included in Meade’s ordering. Wright’s fresh VI Corps, which could have made the forced march to Petersburg in good time, displayed no sense of urgency in its approach.

Grant could share the blame with Smith for his failure to closely control this vital operation. Beauregard showed no such lack of celerity that day. He had played his bad hand with skill. It would be one of the great lost opportunities of the war. Sharpe’s senior scouts, Cline and Knight, had ridden ahead, and Knight would later record the surreal moment when the fate of Petersburg, Richmond, and the war itself hung in the balance:

About 4 p.m. we came out on the high ground to the east and in full view of Petersburg. No Confederate troops were to be seen, and the outer line of works captured by Gen. Kautz a day or two before were standing there unmanned. The troops in the advance were halted and bivouacked for the night. It could not have been over two and half miles from the heart of the city. A little before dark, Cline and I rode down the Prince George Courthouse road, through the works captured by Kautz very nearly to the top of the hill. Some gasworks were just to the right of us. A few shots, not over a dozen altogether, were fired on us. Cline said to me if we had a hundred men we could go in and do what we pleased. My belief was that we could, but next morning it was too late.7

The recriminations over the failure to seize Petersburg had begun. On the surface, the blame could be described as an intelligence failure. Had Smith known that so few men held the lines at Petersburg, he most likely would have swept over them. He was not a timid man, but the lessons of Missionary Ridge and Cold Harbor tugged at his sleeve. The fact was that Sharpe’s operation had begun to break down. Sharpe was now facing a series of major intelligence failures largely outside his control. A good part of the Petersburg fiasco could be laid at the feet of Butler; Petersburg was in the area of operations of his Army of the James, and he had not had a clue as to the depletion of its defenses to pass onto Grant through Sharpe.

A host of circumstances had whittled away Sharpe’s ability keep his hand on the enemy’s pulse. The continuous movement of the army since early May had deprived the BMI of the stable base it needed. Meade was doing nothing to facilitate Sharpe’s work either. On June 8 Sharpe had requested the detail of a Pvt John Smith from the 22nd New Hampshire Cavalry to his scouts. He had heard good things of the man’s abilities and wanted to test them. The next day, the adjutant general responded tartly that “the Commanding General considers that the interests of the service will not admit of an increase at the present time of the force which has been placed at the disposal of the Bureau of information.” Adding insult to injury, Meade had also directed that Patrick report the number of men Sharpe had working for him. In terms of military politics it was a crude demonstration of an utter lack of regard for his services. It was also the type of off hand small-minded insult Meade was wont to throw at his subordinates. Sharpe was not a man to look for an insult, but he knew one when he saw it. In that he was much like the rest of Meade’s increasingly unhappy staff.8

That was also demonstrated as Sharpe himself found his time being consumed by provost marshal duties assigned by Meade. For example, Sharpe had been assigned by a court martial on June 8 to defend, “a negro for Rape on a White Girl…” Apparently Sharpe’s considerable legal talents were insufficient or the evidence overwhelming for the man was convicted and hanged on June 20. Tempers were also fraying. A confusion about the disposition of prisoners threw Meade into “a great stew,” and like the proverbial substance that rolls downhill in a military environment, Patrick blamed Sharpe but later found it was another of Burnside’s bungles.9

McEntee had been sent off to the Shenandoah Valley in a fruitless attempt to stand up an intelligence operation there. Banks simply would not cooperate. That left Babcock alone to control the entire operation which was beyond any single man. In addition, the flat topography had made the heretofore valuable signal intercept system of observation towers useless, and the cavalry was also not being efficiently used to gather information, both sources already out of Sharpe’s responsibility. In addition, Meade had not been too eager to share intelligence with his superior, insisting that reports all go through time-consuming channels from his headquarters to Grant’s. On Grant’s part, his gullibility in reading the raw intelligence derived from prisoners declaring the enemy to be on their last legs had colored his judgment. The absence of an intelligence chief at Grant’s elbow was telling.

Over the next few days the overriding collection requirement for Sharpe was to determine when Lee’s men would enter the fight. The constant movement of the army meant that Sharpe was not able to prepare any reports on the crucial 15th and 16th of June. Only very late on the night of the 17th with the establishment of a base does he resume his reporting. His summary of that day’s interrogations revealed that only Beauregard’s troops appeared to be in the defense. Though there were rumors of reinforcements about to arrive, especially of Hill’s Corps, there was no proof of it; on the contrary, that fact that Beauregard’s forces remained in the front lines without relief was proof that no reinforcements had arrived.10

The next day unleashed a flood of BMI reporting in at least six summaries based on the examination of 863 prisoners and deserters. About a third of these were taken by Butler’s Army of the James, which under Lt. John L. Davenport direction was also extracting information. Now with a secure base, Sharpe’s system could begin to function efficiently, as large numbers of the captured enemy could be processed through the BMI and its Army of the James daughter BMI’s interrogation mills.

The picture began to show that none of Lee’s corps had arrived yet. II and V Corps had taken prisoners only from units under the command of “Beauregard and part of which were sent from General Lee’s army (as Hoke’s division), and represent nearly the whole of Beauregard’s force, at least nine brigades in all. None of them have seen any of the forces properly belonging to any one of the three corps of General Lee’s army.” In a postscript to one of the summaries, he wrote, “I keep steadily inquiring for any of Lee’s army proper, and have so [far] failed to find indications of it.” In the next report, he states, “There is no evidence whatever of General Lee’s having sent any of his own forces to our present front, but all the indications are to the contrary.” He also observed that Beauregard’s brigades were much stronger than any of Lee’s battle-worn ones, averaging 3,000 to 3,500 men. Most of the prisoners taken by Hancock been found asleep while away from their regiments, possibly indicating those units had been dropping exhausted men as they moved.11

At 4:00 a.m. on the 18th Grant struck the eastern defenses of Petersburg with four corps. The attack faltered and then halted, confused by Beauregard’s sudden withdrawal to a second line. When the army did eventually attack, Beauregard stopped it with heavy loss for small gains. Late the previous night Lee was brought word that Grant was definitely on the south side of the James. He immediately ordered Hill and two of Anderson’s divisions to force march to Petersburg. In the late afternoon, the two I Corps divisions filled in on Beauregard’s open right flank just as Warren’s V Corps attacked. Confederate fire swept the field and broke the attack. Grant’s window had finally closed. Lee had arrived. Lee had moved so fast that his coming outran the intelligence that Sharpe had been analyzing. His last report at 9:00 p.m., which reported no proof of the arrival of Lee’s troops, was proven wrong four or five hours before, but Warren’s men had not taken any prisoners to show otherwise.12

About this time Scout Anson Carney returned from a mission but was immediately given new orders by Sharpe:

“General Butler has captured some prisoners near Petersburg. Now, Carney, get on your horse and gallop all the way there and all the way back, even if you kill your horse and see that you don’t get gobbled up, for I want you to get back and let me know what troops have been fighting General Butler to-day; also, whether General Lee’s army has arrived there.”

Carney described his new mission:

I rode rapidly away, some shells passing high over my head enroute. I found the prisoners in a sheep pen guarded by colored troops. Explaining my orders to the proper officer, I jumped over the fence and commenced talking to the rebs something after this fashion: “Well, Johnny, you had quite a skirmish to-day?”

“Yes, we did; and when Uncle Bob [General Robert E. Lee] gets here he will pay you back for it.”

“Hasn’t he got to Petersburg yet?”

“No, but he is coming.”

“What regiment do you belong to?” The regiment was named and then I passed on to another prisoner. In this way I ascertained that only rebel General Kershaw’s brigade had been fighting Butler’s troops, but that this brigade would soon be re-inforced from Lee’s army. I returned to headquarters with the information. It was thought by many officers at headquarters at the time, that if the information had been obtained a little earlier, Petersburg might have been captured that day.13

Sending a scout to interrogate prisoners was another example of how short-handed Sharpe still was at this point.

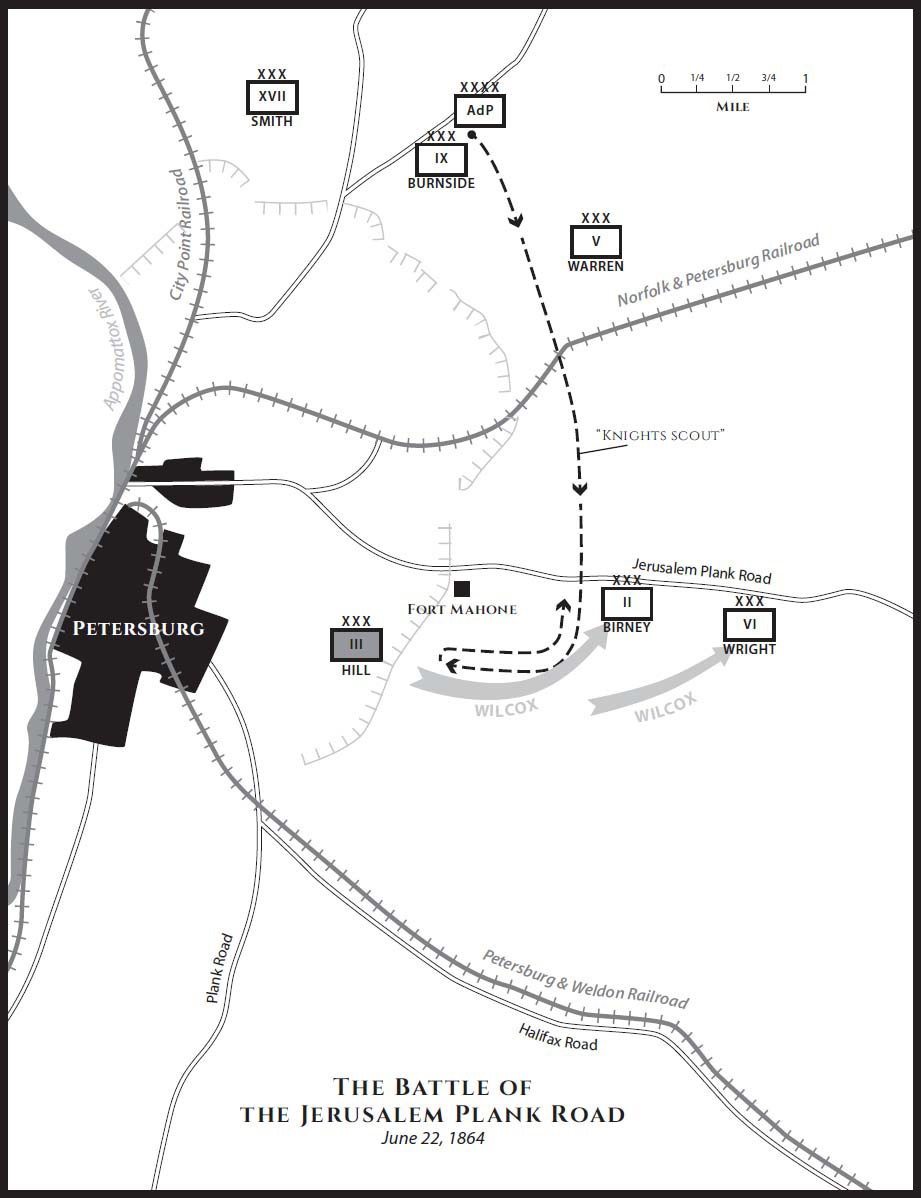

The next day, on the 19th, Sharpe sent out his scouts to find the enemy’s flank. They followed the Jerusalem Plank Road south to an intersection with a western-running road (probably the Weldon Road) where they were engaged in a fire fight with Confederate pickets. They observed the enemy busily building “a considerable earth-work or fort … about a mile and half south of Petersburg.” At 9:00 that night he was able to report that his scouts had successfully found the enemy’s flank. The next day, based on the scouting report, Meade wrote to Grant to tell him that he was going to move two corps to the left and endeavor to stretch to the Appomattox. He also passed on from Sharpe that he had questioned a deserter from the 3rd Georgia Sharpshooters Battalion, Wofford’s Brigade of McLaws’s Division, I Corps, who admitted that they had come into the line late on the 18th. He rated the man’s credibility highly. It appears that the forced march to reach Petersburg had utterly worn out the troops. Surgeons were forbidden to excuse a man from duty save for wounds. In another report of the same day, the BMI had also ascertained that A. P. Hill’s III Corps had arrived on the evening of the 18th. Within a day and a half of their arrival the BMI was able to discover that I and III Corps were now manning the Confederate flank. Sharpe was also actively gathering information, through his scouts and interrogations of local civilians, on the location of important facilities such as water works and reservoirs supplying Petersburg, information which was quickly passed down to the corps commanders.14

The army was now about to profit from the initiative of Sharpe’s resourceful scout Knight, as he would recount:

After we had been in front of Petersburg for a week or two, although we had been busy and done some hard work, it seemed to me that it was time something tangible should result from our service. Both armies were extending their lines to the left. There was no reason that all of us should stay in camp every night, and I concluded to make a night-trip and see if I could learn anything of importance.

He left headquarters on the night of June 21 without permission or a pass and slipped out the same way a rebel scout within their lines would take to return to his own lines. In crossing the Jerusalem Plank Road not far south of Fort Hell, he observed B Battery, 2nd New Jersey (II Corps), whose commander he knew. II and VI Corps were preparing to move forward the next day to tear up the Weldon and Petersburg Railroad. Halfway to the railroad, he turned north and approached the Confederate lines and bedded down in a place that would give him good observation. The next morning he watched in amazement as Hill’s III Corps assembled. It was obvious that they were planning an attack. Knight realized he could never get back to headquarters in time to deliver a warning. He realized he had no credentials and that he was unlikely to be recognized by any of the senior officers in II Corps. He did know Capt. Judson Clark commanding the guns of the 2nd New Jersey. The ground was so open he had to snake or low crawl a considerable distance before he could rise to his feet and rush to find Clark.

Clark believed him, but an infantry colonel commanding a regiment who was present dismissed him out of hand. Only Clark put his command in readiness to meet an attack. The Confederates fell upon the unsuspecting II Corps like a hammer, driving it back and taking several thousand prisoners. Only the steady and courageous action of Clark’s battery prevented a greater debacle. It was a perfect example of the fact that a necessary predicate for surprise to be sprung is that the victim refuses to believe evidence of its approach. After returning to camp, Knight heard the noise of what would be called the battle of Jerusalem Plank Road erupt from the direction of II Corps. He decided to keep the entire episode to himself. Nevertheless, it was an example of the consistent resourcefulness that marked him to Sharpe as a man worthy of greater things.15

Now that the armies had settled down around Petersburg and Richmond and Lee’s I and III Corps had been identified in the lines, a BMI collection priority became to answer the question of where was II Corps. Sharpe did not yet know that Early had replaced Ewell. Sharpe’s intelligence summary of June 17 to Meade was the first he had been able to prepare in over a week, but it did not warn of II Corps’ absence. There had been such tightened security and such thick lines of pickets to mask the departure of II Corps the previous week that deserters found it impossible to slip away.

Sharpe would not obtain the first evidence that the corps were missing from the front until June 20. That same deserter from the Georgia Sharpshooters also gave a clear and accurate account of just what had happened. “He says that Ewell’s corps [apparently the prisoner did not know Ewell had been replaced either] left General Lee at Cold harbor; that it was understood to be going toward the Valley or Lynchburg; at all events, he has not seen any part of it since, and is quite certain that no part of General Ewell’s corps is in our front.” By the time Sharpe learned this, Early had already defeated Hunter at the battle of Lynchburg and begun to drive him out of the Valley, fulfilling the first part of Lee’s orders. On the 21st there was more confirmation from prisoners of the presence of I and III Corps with information on the location of their divisions, and more evidence that II Corps was absent. “They agree that Ewell’s corps is nowhere near them, but say that it left them at Cold Harbor, and they have not seen it since. They think from all they have heard it has gone to Western Virginia.” There was also the news that “Anderson has been made a lieutenant-general, and now commands Longstreet’s corps.” The next day the interrogation of more prisoners showed that “They know nothing of Ewell” but could identify most of the divisions of the other two corps.

Sharpe felt worried enough to send off his chief of scouts to find II Corps in the lines around Petersburg. Cline had just come in from a reconnaissance on the 23rd, when Sharpe sent him back to obtain evidence and not to confine himself to the environs of Petersburg and Richmond. He had every confidence that Cline could handle a long-range mission. In his summary of that day, he stated emphatically, “I can hear nothing of Ewell’s corps.” On the 24th Sharpe summarized another prisoner interrogation. “I am satisfied from examination of this man, who is a great talker and blow-hard, that no part of Ewell’s corps has returned or is in this vicinity. He says he heard, a day or two ago, that Ewell’s corps had captured Hunter, but he does not seem to believe the report.”16

It was only on the 28th that news of the Confederate victory in the Valley trickled in from McEntee. His report was the first accurate information on the size and whereabouts of Early’s Corps. Trying to put a good face on it, he added, “By hard marches, closely pursued by the enemy, we got off without disaster. We have marched farther into the Confederacy, and injured the enemy more, than any column that has ever marched in West Virginia.” Unfortunately, McEntee opined that Early was already returning to Lee’s army at Petersburg, and Grant agreed, as William Feis argues:

Grant agreed with the assessment, perhaps based upon the conviction that Lee needed every man to defend Richmond and Early had departed before the danger posed by the movement across the James had become clear. Given the circumstances, Lee would have little choice but to recall the detachment, making McEntee’s conclusion provable. And before long, more intelligence emerged to support the captain’s assessment.

That was in the form of a report from Hancock of the statement of three deserters who reported that “Ewell’s [Early’s] corps arrived yesterday [June 30th] and that part of it was marching to [the Confederate right]. He was so satisfied in mind that this was so that he brushed off Halleck’s telegram of the same day that the enemy was now positioned to raid Maryland or Pennsylvania. Grant replied that “Ewell’s [Early’s] corps had returned here.”17

On July 1 as well, McEntee wrote Sharpe a long, revealing letter from Charleston, West Virginia. It is not known when or if Sharpe received it:

I telegraphed you on the 28th giving you the results of our Lynchburg fight and the forces we engaged there. The only prisoners taken by us were from the 54th N. C. Infantry. They all stated that the whole of Ewell’s Corps was there. We had other information that they were there, but at the same time I seemed to be much doubted by the general and his chief of staff, and for that reason I stated that a part of that corps was at Lynchburg… I am at present A. D. C. in General Hunter’s staff, but as I have drifted entirely out of my [?] as the means of communicating with you have been so imperfect I have asked to be relieved here and ordered to the Army of the Potomac.

It appears that McEntee’s assessment of June 28 had been heavily influenced by Hunter and his staff and that although he had arrived at the correct enemy order-of-battle it had been disregarded. Other communications he subsequently sent which might have clarified his comment that Early was returning to Richmond had not been received by Sharpe. The intended positive relationship between the commander in the Valley and his new BMI had failed to materialize to the point where McEntee was desperate to return to the Army of the Potomac. He provided another piece of information that would be of use later. He had encountered many Union deserters who were using the Valley to attempt to get back north.18

By the first few days of July, alarmed reports from Union commanders in the northern Valley of Early’s continued advance had reached Washington. Lincoln, Stanton, and Halleck consulted Grant, who insisted Early was still in front of him at Richmond. He again asked Meade if he could confirm Early’s presence. Clearly briefed by Sharpe, Meade replied cautiously. “The only information I have as to Ewell’s corps was derived from deserters, who said it had returned from Lynchburg. No prisoners have been taken from any of the divisions of that corps or any other information obtained than above. It was never reported as in our front, but only that it had returned from Lynchburg.”19

In the midst of this unfolding intelligence crisis, Patrick, in response to direction from Meade, sent Sharpe and Colonel Gates of the provost guard’s 20th NYSM on July 3 to investigate the report of the rape of two “young ladies” by some of Sheridan’s cavalry at Douthat’s Landing across the James from City Point. Sharpe left immediately for City Point, and the next morning Gates and he took a tug across the James. After questioning the locals, they found the report was unfounded. Sharpe did add, “There were excesses with the negro women there, but they rested upon evidence which I considered secondary and conflicting and that I was not authorized to investigate.” This assignment was indicative of the lack of priority given to Sharpe’s intelligence mission, especially since he was gone for two days as the crisis over the whereabouts of Early’s Corps was reaching the boiling point.20

Back at work on July 4, Sharpe learned from a deserter whom he judged reliable that rumors in the Confederate camp placed Early on Arlington Heights overlooking Washington and ready to pounce on the capital. Grant chose to discount Sharpe’s judgment and wired Halleck the same day in words of studied denial:

A deserter who came in this morning reports that Ewell’s corps has not returned here, but is off in the Valley with the intention of going into Maryland and Washington City. They now have the report that he already has Arlington Heights and expects to take the city soon. Of course the soldiers know nothing about this force further than it is away from here and north somewhere. Under the circumstances I think it advisable to hold all of the forces you can about Washington, Baltimore, Cumberland, and Harper’s Ferry, ready to concentrate against any advance of the enemy. Except from the dispatches forwarded from Washington in the last two days I have learned nothing which indicated an intention on the part of the rebels to attempt any northern movement. If General Hunter is in striking distance there ought to be veteran forces enough to meet anything the enemy have, and if once put to flight he ought to be followed as long as possible. This report of Ewell’s corps being north is only the report of a deserter, and we have similar authority for it being here and on the right of Lee’s army. We know, however, that it does not occupy this position.21

In a letter of the same day, Grant’s alter ego, his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. John Rawlins, wrote that General Hunter should be able to concentrate enough forces at Harper’s Ferry to forestall Ewell’s (Early’s) descent upon Washington. He did unintentionally compliment Sharpe by citing the strength of Ewell’s (Early’s) army at not much than 15,000, a most accurate BMI calculation.22

The next day Grant’s complacency begins to change. He must have reconsidered his hasty conclusion and wired Halleck at 12:30 p.m. “If the enemy cross into Maryland or Pennsylvania I can send an army corps from here to meet them or cut off their return south. If required, direct the quartermaster to send transportation.” The situation in Washington had changed overnight. Halleck wired him at 1:00 p.m. of chaos along the upper Potomac from Harper’s Ferry to Monacacy. The enemy had cut the wires and destroyed the bridges. What few Union forces there were in the area were falling back.

We have nothing reliable in regard to the enemy’s force. Some accounts, probably very exaggerated, state it to be between 20,000 and 30,000. If one-half that number we cannot meet it in the field till Hunter’s troops arrive. As you are aware, we have almost nothing in Baltimore or Washington, except militia, and considerable alarm has been created by sending troops from these places to re-enforce Harper’s Ferry.

He then begged Grant to send him all his dismounted cavalry.23

By 10:30 that night Halleck now felt the situation was easing. Thirteen hundred troops from Hunter were expected in time to deal with any problem. His earlier apprehension seemed to fade behind the conclusion that only an enemy raid had occurred.

As Hunter’s force is now coming within reach, I think your operations should not be interfered with by sending troops here. If Washington and Baltimore should be so seriously threatened as to require your aid, I will inform you in time. Although most of our forces are not of a character suitable for the field (invalids and militia), yet I have no apprehensions at present about the safety of Washington, Baltimore, Harper’s Ferry, or Cumberland.

Like a good planner, however, he recommended Grant subordinate all the water transportation assets at Fort Monroe and the James River be placed under Meade’s quartermaster, Ingalls.24

Sharpe added more grist for Grant’s mill on this subject during the flurry of telegrams between Washington and City Point where Grant had set up his headquarters. Sharpe’s summary from the interrogation of two deserters from the 20th Georgia Battalion Cavalry stated, “it was currently reported within their lines, both at Richmond and in Petersburg, that General Early was making an invasion of Maryland, with the intention of capturing Washington, having under his command two divisions of Ewell’s [Early’s] Corps…” At 1:00 p.m. Meade sent Grant what appears to be a summary of this report, with a few more details: that the force consisted of two divisions of Ewell’s Corps, with Breckinridge’s command and other forces, to capture Washington, “supposed to be defenseless. It was understood Early would reach Winchester by the 3rd instant.”25

At 11:50 p.m. Grant wired Halleck in response to his telegram of 1:00 p.m., stating he had ordered the dismounted cavalry and an infantry division to be followed by the rest of VI Corps, “if necessary. We want to crush out and destroy any force the enemy have sent north. Force enough can be spared from here to do it.” Then for the first time he admitted that it could be Ewell, probably based on Sharpe’s last report, by ending his message with “I think now there is no doubt but Ewell’s corps is away from here.”26

On the 6th Sharpe prepared another summary about information obtained from a deserter from the 2nd North Carolina Cavalry, with the type of information that just leaps out at an experienced interrogator and analyst.

Very little is known in their army of the whereabouts of Ewell’s corps. It was reported to be operating in the Valley. Informant thinks it is certain that it is not here, for convalescents and furloughed men belonging to Ewell’s corps are under charge of the provost-marshal at Petersburg awaiting its return.

Early’s convalescents and furloughed men would have been returned promptly to the corps if it had been in the lines at Petersburg. The fact that they were collected all in one place by the provost marshal was a statement that the corps was far too distant to have sent them. Another less credible deserter who admitted knowing nothing about II Corps thought Ewell was with his command down the railroad. He had probably heard about Ewell being in the area as he was on other duties.27

Sharpe also reported that another deserter brought a Richmond newspaper of the 6th, which reported the capture of Harper’s Ferry by Early. That caused some confusion since Grant had been in communication with Harper’s Ferry that very day, and it was in no danger. In fact, Early bypassed the town, and the newspaper report was just inaccurate reporting. This did not stop Grant from ensuring that the promised forces were dispatched that very day to Baltimore—2,500 dismounted cavalry and 5,000 men of Rickett’s Division of VI Corps. His staff had been working through the night, and orders were issued before daylight. At 3:30 p.m. Grant wired Halleck, “I think there is no doubt but Early’s corps is near the Baltimore and Ohio road, and if it can be caught and broken up it will be highly desirable to do so.” This is the first indication that he had fully accepted Early’s presence on the Potomac.28

Halleck next wired Grant that the situation had worsened. Sigel had no scouts and could only guess that the enemy numbered 7,000 to over 30,000. He had other estimates that placed them at 20,000 to 30,000. “I think there is no further doubt about Ewell’s corps. Probably, also, Breckinridge’s, Imboden’s, Jackson’s, and Mosby’s commands. If so, the invasion is of a pretty formidable character.” He had lost contact with Hunter, and the railroad that would have brought his troops had been wrecked. He then asked Grant to send him a good major general to command the troops to command in the field. Unfortunately, this message was not received until the next day.29

The reinforcements arrived by the 8th. Halleck sent Ricketts on to join Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace’s green troops at Monacacy to stop Early if they could. He complained that of the 3,000 dismounted infantry that had arrived, 2,496 were sick. When Meade had passed on Grant’s orders to send dismounted cavalrymen to Washington, he apparently did not explain the reason. Sheridan had that many sick who were by definition dismounted and rid himself of them. Though he informed Meade through Humphrey, no one seemed to notice.30

Captain McEntee had arrived in Baltimore on the 7th, where he wired Sharpe for instructions. The wire eventually got through but took so long that Sharpe’s reply—which told him to report to Wallace if he felt he could be of use and was addressed to his Baltimore hotel —never got to him; he was long gone. The next day McEntee had not heard from Sharpe and became alarmed at the reports of Early’s force being in much greater strength than Hunter had opined. Then, on his own initiative, he took the last train into Harper’s Ferry to be able to monitor events, presumably with his two scouts. He could not communicate with Sharpe again until the 12th because, as he wrote, “I am surrounded by rebels and torn-up railroads.” Despite that he was able to construct an accurate order-of-battle of Early’s command. He identified the three II Corps divisions commanded by Rodes, Ramseur, and Gordon, and the one composite one. As well, he identified how Early had split his force into two small corps by uniting Gordon’s Division with the composite one and giving its command to Breckinridge. Early made these changes on June 24, changes that McEntee picked up within two weeks. McEntee was less accurate when he put Early’s strength at 20,000—25,000 men. He thought Early’s Corps was 12,000 strong and that the other elements of his overall command added another 10,000. Early, however, had only 8,000 men in his II Corps when he departed for Lynchburg. Altogether the Army of the Valley amounted to only 14,000 men. Since McEntee did not have access to Babcock’s painstakingly kept order-of-battle records, it was an excusable error.

McEntee had put the order-of-battle together by interrogating prisoners and through information from a useful agent, but there were limits to what he could do.

I would have gone out today but General Howe objects as he wishes me to remain with him until General Hunter arrives thinking I can do him more good than I can you. I can neither get a horse here for love nor money or would have followed the enemy up. Probably you know more of their whereabouts than I can tell you as I only give you the most reliable rumors. I have seen many of the prisoners and have their organization. The local commander refused to let me go scout personally.31

In all this confusion over Early’s location, the same question was now asked of Anderson’s I Corps. Sharpe provided the answer. Two contrabands, servants at Anderson’s headquarters, had been captured when they tried to graze their horses between the lines. They identified the location of Anderson’s headquarters and affirmed that the entire I Corps was indeed in the lines at Petersburg and then proceeded to identify the location of each division. They identified Beauregard’s Corps on the left and Hill’s on the right of their own corps. They also stated that probably Heth’s Division had moved out onto the extreme right near the railroad. This is some of the most accurate reporting Sharpe had seen. The Confederates paid no mind to their servants as security risks, thinking of them as merely furniture. Yet time and time again observant slaves had noted in detail what was going on around them. Charlie Wright in the Gettysburg Campaign was one such piece of furniture whose retentive memory set the Army of Potomac in motion. Meade immediately forwarded Sharpe’s report to Grant and followed it up by writing, “I have no doubt Longstreet’s corps is here.”32

Sharpe’s multiple collection sources now provided incontrovertible proof of what the interrogation reports had been saying. On July 9 Sergeant Cline, whom Sharpe had sent out from Petersburg to find II Corps wherever it may be, reported Early’s exact location. He had conducted another of his scouting miracles by riding through Early’s camps located on South Mountain between Hagerstown and Frederick, Maryland. That same day Early defeated Lew Wallace’s scratch force at the battle of the Monacacy near Frederick. At that time Grant had no idea how much he owed to Wallace’s desperate delaying action. Cline’s report and a wire from Halleck who reported on Wallace’s defeat at Monacacy and his estimate that he faced one-third of Lee’s army drove Grant to decisive action. He immediately sent Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright and the rest of his VI Corps to Washington and directed that XIX Corps, which had earlier been ordered up from Louisiana to reinforce his Armies Operating Against Richmond, also be sent.33

The pot had come to a boil outside Washington on July 11 as Early completed his reconnaissance and ordered an assault which broke down under a combination of exhaustion of the troops and the discovery of whisky barrels in the looted mansion of Preston Blair. VI Corps troops arrived the same day to stiffen the defenses. The next day growing Union strength decided Early against an attack. He withdrew that afternoon and was south of the Potomac the next day. On the 11th Grant dispatched Sharpe to Washington and Baltimore to supervise the intelligence operation from closer to the crisis. His presence brought some calm to the civilian leadership of the government. He joked to his Uncle Jansen that his “coming was well timed to allay” his wife’s “fears about the invasion!” He knew the size and nature of the threat precisely. “The two infantry divisions under Early, & one under Breckenridge [sic] with the scattering of odds & ends left in W. V. numbered from 23,000 to 25,000 men. I knew every regt and had an estimate of them by regimental strength.” That calm assurance steadied the nerves among the civilians in the War Department which “was not stampeded.” He had great faith in the competence of Maj. Gen. Christopher Columbus Auger, the commander of the District of Washington, as did Grant, but realized that he had few competent subordinates. Grant had combed the district thoroughly of able men to replace his losses. “But,” explained Sharpe, “in the desire to provide for incapables & politicians there was not a live man near Washington to handle the troops.”34

Sharpe closed his letter by venting a soldier’s common complaint of the cost of political favors and deal-making. “When we shall relentlessly cut off the head of every failure, without regard to tickling Republicans or propitiating Democrats, then will the enormous preponderating resources of the north close up this thing & not before. And while we are waiting, we must pay.”35

Sharpe had the last laugh, though, and possibly a windfall from the matter. Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Lyman of Meade’s staff wrote in his diary on Sharpe’s return, “Col. Sharpe has been to Washington where they all were sweating with fear! He told them Early had not over 25,000 men; they swore he had 92,000 including all A. P. Hill. He offered a heavy bet they would all fall back the moment the VI Corps reappeared in front of Washington; and it came to pass!”36

Lincoln was not so assured. Perhaps it was nearly getting shot at Fort Stevens which Early’s men had taken under fire on the 12th that caused him to wire Grant that same day. “Vague rumors have been reaching us for two or three days that Longstreet’s corps is also on its way to this vicinity. Look out for its absence from your front.” Halleck wired also that, though the capital was now “pretty safe” for the present, prisoners and civilians were claiming both Longstreet and Hill were expected. Sharpe’s reporting had clearly shown that both corps were in the defenses of Petersburg. The same day, Meade was fuming about the problem of keeping track of the divisions of those corps.37 Lee kept them busy, regularly relieving divisions in the forward lines with divisions in reserve and in shifting them to extend his flank. Meade vented to Grant, “I send you the latest information received. It shows how conflicting is the information we receive, and how accurately the enemy is posted in our affairs. Mahone’s division, of Hill’s Corps, has now been positively placed in our front, on our left and rear, and on its way to Pennsylvania.” If Meade had not insisted on being his own senior intelligence officer, his staff might have given him a better answer.38

Nevertheless, nailing down that Longstreet had not left Lee’s army became a collection priority for the next three days. Then as now, presidential inquiries were taken with great gravity. On July 12 Babcock provided the definitive proof. The next day Rawlins was writing, “It is positively asserted [in Washington] that Longstreet’s corps is on the way there, but we have the best of evidence that it remains here, and it is here I have no doubt. We have deserters from it daily and also make captures of prisoners from it. This latter evidence has never failed us.” Based on a report from Babcock, Meade informed Grant on July 15, “There is no evidence in the provost-marshal’s department of any part of Longstreet Corps having left Lee’s army.” But it is clear from Rawlins’s letter that Sharpe had already shown Grant and Rawlins the results of Babcock’s analysis.39

On the day after Monacacy Lee wrote to Jefferson Davis, sending him a copy of the July 8 issue of the New York Herald, with the note:

You will see that the people in the U.S. are mystified about our forces [Early’s expedition] on the Potomac. The expedition will have the effect I think at least to teaching them they must keep some of their troops at home & that they cannot denude their frontier with impunity. It seems also to have put them in bad temper as well as bad humor.40

It did indeed put Grant in a bad humor. He had learned a lesson. His inattention to intelligence had nearly allowed Early to seize the Federal Capital. It was the sort of near-death experience that provokes a fundamental reassessment of what went wrong.

Wright’s timely arrival to forestall Early was not the end of alarm in Grant’s command over the threat to Washington. There was plenty of “bad temper as well as bad humor” within the Union high command at City Point. The same day that Wright reached Washington, Babcock, in a report of that morning, informed Meade that a just- interrogated deserter, from the 8th Alabama of Mahone’s Division of Hill’s Corps, revealed that his division had left its position while he was in Richmond on pass. He stated that Hill’s entire corps had left the lines at Petersburg at 5:00 p.m. the day before (the 10th) and moved toward the Weldon Railroad. Civilians in Petersburg told him they were headed to Pennsylvania. Meade immediately forwarded Babcock’s report to Grant at noon with the following postscript: “There is no doubt that Hill’s corps or portion of it moved last evening, but there is nothing to indicate the direction taken. It may prove a movement on our left flank due to the withdrawal of the VI Corps. I have directed the cavalry on our left to push scouts out in all directions.”41

At 1:30 p.m. he reported anxiously to Grant that he had personally interrogated the deserter. “He says Heth’s division left about the same time, and that he heard in Petersburg a report that Hill’s Corps was going to Pennsylvania.” He was careful to note that his signal officer reported, per contra, that two trains filled with troops and artillery had actually come into Petersburg that same day. Nevertheless, he concluded, “I think there is no doubt Hill has moved, but in what direction is as yet uncertain. It may be on our left flank or it may be to join Early.” The story had all the earmarks of one of Lee’s disinformation operations, in which he sent deserters into the Union lines with carefully constructed stories meant to mislead and confuse. This would have been the perfect time to capitalize on the now extreme Union sensitivity to Washington’s security as he had pointed out to Davis in his letter of the 10th.42

If it was a trap, Meade fell right into it. If not, he simply fashioned a rod for his own back by accepting without corroboration the deserter’s story. In either case, Lee would have been pleased because the story that Hill had departed to join Early in another invasion of Pennsylvania took on a life of its own. Grant smelled an opportunity here and replied almost immediately. “If Hill’s Corps has gone we must find out where it has gone and take advantage of its absence.” He discussed a major turning movement of the enemy’s right at Petersburg combined with a heavy assault on their lines to fix them in place. Meade responded the same day that though there was “no further information … of the enemy’s movements … I conclude they have been sent to re-enforce Early.” He continued, “Intelligence of Early’s success, combined with knowledge of the departure of the Sixth Corps, together with a confidence in the strength of his lines and his capability to hold them with a diminished force, has doubtless induced Lee to send Hill in hopes of thus transferring the seat of operations to Maryland and Pennsylvania, by drawing the greater portion of your army there to defend Washington and Baltimore.”43

Meanwhile, Sharpe was trying to throw a net over this growing general officer speculation. He interrogated another deserter, from the 48th Mississippi, on the same day as the wires were humming between Meade and Grant. This man stated that as of the previous night, both Mahone’s and Heth’s Divisions of Hill’s Corps were still in place in the defenses of Petersburg. He stated that Heth’s Division was under marching orders, but his own, Mahone’s, was not. Sharpe then confronted the deserter, who had told Meade of the departure of Hill’s entire corps for Pennsylvania, “why their statements were so opposite.” Sharpe then speculated that they were both right and that the latter, whom he thought a man of “considerable intelligence,” may have well thought that to reveal Hill’s departure would have been dishonorable. This was a mistake. Sharpe was giving in to the old trap of “making the wish the father to the thought.” Nevertheless, he was still in the process of cross-checking this information and later in the day sent his scouts to Petersburg to see what they could learn. Meade was anxious for any new information, and on the 11th asked, at 10:15 p.m., if Sharpe had heard from them. Sharpe replied that they should be back in the morning.

That morning another deserter who had come into Union lines the night before stated that a friend had told him all of Heth’s Division and Wright’s Brigade of Mahone’s were on the move to counter a Union move to cut the Weldon Railroad. Scout Carney also reported in that morning. He had contacted a Union agent at Ennis’s farm the day before who was cradling oats all day in sight of the railroad. In the afternoon he saw troops, about division size, passing south on the Halifax Road, passing Ream’s Station and then onto the Jerusalem Plank Road. The agent had been watching the train for the last several days and stated clearly that no troops had passed on it. Babcock commented that the scout had tasked the agent to find out what he could about the troop movement and where the division had gone.44

On the morning of the 13th, Babcock reported that deserters from Mahone’s Division said that Wright’s Brigade and Heth’s Division had arrived back in their original positions at daylight the day before. Babcock provided a drawing of the positions of all of Mahone’s brigades, including Wright’s in reserve. New deserters corroborated this story. Shortly after receiving this, Meade wired Grant to put the entire matter of Hill’s disappearance to rest.

The above dispatch forwarded for your information. It proves Hill’s two divisions are still in our front. It confirms the movement of Heth previously reported, and is in conformity with Gregg’s report [from the cavalry] that he could find no infantry at Reams’. I now think the enemy having heard of Wright’s movement sent Heth to Reams’ to meet an attack on the road, which not being made, he was brought back…

It had certainly been an exciting two days but unnecessarily exciting. Meade had rushed to conclusions based on a single report—which had one statement picked up by a soldier from civilians in Petersburg that Hill was on his way to Pennsylvania—without waiting for his analysts to cross-check and confirm its accuracy. In other words, he immediately lent great credence to a major threat to the North based on civilian rumors, or, as it is facetiously called today in the Intelligence Community—RUMINT (Rumor Intelligence). After summoning this monster from the Aladdin’s lamp of rumor, he had to turn to Sharpe’s analysts to confirm or deny it.

The near loss of the capital had a sobering effect on Grant. Whatever his wishful thinking had contributed to the intelligence failure, he could see that things needed to change. Clearly, he needed better intelligence support, and he saw Sharpe and the BMI as the solution. He was faced with Meade’s touchy truculence in guarding his prerogatives as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Grant resolved Sharpe’s awkward command relationship in a typical general officer fashion. Even before Early’s raid on Washington had turned back, on July 4 he redesignated the provost marshal of the Army of the Potomac as the provost marshal of the Armies Operating Against Richmond, making it directly subordinate to himself. He was killing two birds with one stone. He did need a single staff to control provost marshal functions among the several armies he commanded. Undoubtedly, it also hid his other priority—to wrest Sharpe and company from Meade.45

By this time, Grant had not only become a believer in the value that Sharpe offered but had become personally fond of him. Sharpe was an attractive and engaging personality and a great storyteller. It was a talent that enlivened the moments between battles and one that no doubt relieved the burdens of command for Grant. It was also a talent that Sharpe consciously used to establish his relationship with the general-in-chief.46

The change quickly became common knowledge as Gates noted that Patrick traveled to City Point on the 5th to make arrangements, “to establish his Hd Qtrs here as Pro. Mar. Gen. of the Armies operating against Richmond and the lines of communication.”47 On his arrival he had an interview with Grant, who was trying to have it both ways. Patrick wrote of his interview, “The Object is, to have a Central power to regulate Butler & others, but, as Grant expressly says, not to take me from the Army of the Potomac.” Patrick returned that night to see Meade, who was in a fury, not with his provost or with Grant but with “every body & thing. He had learned that his Staff would, all, gladly leave him, on account of his temper, and he had become desperately cross.” He told Patrick he would find a replacement for him and “that he would not have any partnership with Grant, etc. etc.”

Contributing to Meade’s foul temper was his constant crucifixion in the press, stemming from an incident at Cold Harbor in early June. Meade had claimed that a reporter from the Philadelphia Inquirer, Edward Crapsey, had libeled him. He ordered the man, in Patrick’s words, “placed on a horse, with breast & back boards Marked ‘Libeller of the Press’—& marched in rear of my flag, thro’ the Army, after which he was sent to White House & hence North—He was completely cut down—It will be a warning to his Tribe.” It was the sort of warning that backfired. The reporters with the army agreed to never mention Meade’s name again in the press in a positive light and ascribed advance to Grant or the Army of the Potomac.

Meade’s anger had already been stoked over the BMI. A few days before the blow-up on the 5th, there had been another knock-down, drag-out argument between Meade and Patrick, and this was over the BMI. Meade had said that “the whole Bureau of Information was good for nothing—that it furnished no information not already received thro’ the Cavalry—that it ought to be broken up & that Genl. Grant thought so, too.” Patrick leapt to the defense of the BMI. “I disagreed with him entirely and told him that he had refused to let us do what was desired & which we knew to be for the best interests of the Service—I therefore told him, that I proposed to transfer that Bureau to Genl. Grant’s Head Quarters & there give it a trial, when, if it still proved worthless, it should be disbanded.”

That just fanned the flames of Meade’s anger. He said that “he would not permit the transfer, but that he would allow it to be broken up.” Patrick vehemently took issue with Meade’s treatment of his staff as if they were personal servants.48

On the 6th Patrick rode back to City Point and had an interview with Brigadier General Rawlins, Grant’s chief of staff. He agreed to relocate his operation to Grant’s headquarters at City Point. It was agreed that “The Scouts, Guides, etc. with [Col.] Sharpe & [Capt. John C.] Babcock, remain here, until the questions now at issue between Meade & Grant are settled.”49

Patrick next day then sought advice from Burnside, whose opinion, as a former commander of the army, he valued. Burnside strongly insisted that on no account should Patrick resign as provost marshal general of the Army of the Potomac, unless Grant proposed it. He also advised with a great deal of shrewdness, “to run the machine for the A. of P. to the best of my ability, taking such members of my Staff & of my Organization, as were necessary to carry out the orders of Genl. Grant, & let Meade do what he thinks his dignity demands.” It was common sense advice that Patrick adopted. He simply decided to carry on his duties without reference to anyone’s jurisdiction. On the 7th, Patrick actually set up shop at City Point. Sharpe joined him that evening. The old provost marshal was playing it by ear, and Sharpe was shrewd enough to take his cue from him. And that ear told Patrick to return to Meade’s headquarters when Meade sent him a cutting telegram on July 9, stating his departure for Grant’s headquarters at City Point was unauthorized. He returned and had dinner with Sharpe. Meade would not see him. The dispute had already become public; Gates recorded the Meade summons in his diary, and predicted, rightly, another row.50

Grant went to great lengths to placate Meade. He was well aware of how touchy Meade was and did not seek an open confrontation which would likely have led to the latter’s resignation. He did not actually publish the order appointing Sharpe as assistant provost marshal of the Armies Operating against Richmond until December 2. In the meantime, most of the BMI operation remained with Meade’s headquarters, in a classical compromise of military turf, described by Edwin Fishel: “Sharpe had desks both there and at AOAR headquarters at City Point … in addition to meeting with Grant almost daily, he spent hours there working with Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Bowers, a member of Grant’s staff, who by this association would become familiar with the details of the Sharpe-Babcock operation.”51

Sharpe explained to his Uncle Jansen how he was dealing with the problem. “I am now by the way alternating in my duties at H. Q. Army of the Potomac & here at H. Q. Armies of the U.S. in the field, of which [the] latter Genl Patrick is the Pro Mar Genl. He comes down occasionally for a day or two, & then I return to represent him. My interviews with Genl Grant are frequent—generally every day.” It was a situation in which familiarity did not breed contempt, rather just the opposite. “I have a strong liking for his entire simplicity & truthfulness of character united to a great firmness & decision.” His budding case of hero worship went so far as to agree with the hated New York Herald that “Uncle Abe” should step aside for Grant in the 1864 election.52

The result of this keeping a foot in both headquarters to placate general officer egos, according to Fishel, was:

Thus there were now two intelligence centers; deserters and other suppliers of information were received at both, reports issued from both, and Sharpe and Babcock spent as much time writing telegrams and notes to each other as they did in face-to-face discussion. At one point when McEntee was substituting for Sharpe at City Point, he and Babcock made estimates of Lee’s strength, each unaware of the other’s calculation; the two figures differed by only 600. The two totals, about 50,000, were 12 percent below the number of effectives shown on Lee’s rolls.53

In practice, Babcock replaced Sharpe in Meade’s eyes as his chief intelligence officer, and Babcock reported directly to him as the notes from the one to the other demonstrate. Babcock considered that he served under Grant through Meade. That meant he also worked for Sharpe. It was a deft juggling performance that he carried off with aplomb. This arrangement would have confounded the maker of an organization chart, but it worked.54

Meade continued to act out the charade of his control over Sharpe’s bureau by sending Grant copies of its reports that the latter was already receiving from Sharpe. There was a distinct difference in how the two commanders treated the BMI. Meade for over a year had limited Sharpe to only the collection sources under his direct control. Grant expected Sharpe to use an all-source approach to prepare his intelligence reports and briefings. This situation continued to play out for the rest of the war. While it formed a sort of grudging truce between Grant and Meade, it certainly made the work of Sharpe and his staff much more difficult. While this is a common outcome when general officers lock horns and then back off, their subsequent jury-rigged compromise rarely makes the work of their subordinates easier. The fact that the provost marshal and BMI team were able to work with this situation and prosper, is a credit to both their talent and professionalism.

Although Sharpe reported to Grant for intelligence operations, he responded to any order Patrick might give him since he remained deputy provost marshal. He recognized that Patrick had repeatedly acted as his benefactor and repaid him with good will and friendship. He managed to take in his stride any additional duties required by Patrick. Gates recorded that on the 8th, Sharpe, another officer, and he had composed “a board to examine into the circumstances of the sinking of the Schooner Ashland by the Steamer Tappahonnock.” They held their board on the steamer Young America in the James River; the proceedings took most of the day.55

Despite the general officer politics, Sharpe indisputably worked for Grant first and foremost from that time on. Almost immediately, he dispatched a senior scout, Judson Knight, with instructions to take 10–12 of the best scouts and commandeer quarters for the group at the City Point headquarters of the Armies Operating Against Richmond. He chose a small frame building that had been used as a marine hospital and within two days was ready for new missions. Sharpe’s choice of Knight clearly showed his growing appreciation of the man’s abilities. He may have been grooming him as a replacement for Cline when the man’s enlistment would expire the next month. The change of headquarters breathed new life into Sharpe’s staff, which started to use its own BMI letterhead stationery for the first time.56

As Sharpe was settling happily into his new role, he received startling news from a Kingston visitor that his name was being prominently discussed as a candidate for Congress. He claimed to Uncle Jansen, “This is the first time I have heard a thought of such a thing—& while I don’t desire and would not manipulate for it, I would not kick away a thing that comes in a proper way, with good chances of success.” Sharpe was an ambitious man and to say that he had never even thought of Congress, given his social and growing prewar political activities, might have been a case of “Methinks the lady doth protest too much.” In any case, his candidacy would put him squarely in opposition to the sitting Congressman, his former law partner, friend, and benefactor, John Steele. That was something he would not do. Nevertheless, the idea was flattering, and despite his statement that he would speak to no politician about it, he asked Uncle Jansen to “tell me if you really think there is anything to it.” The coming heavy combat would drive thoughts of running for office from Sharpe’s mind, though the political bug would end up biting his friend, Colonel Gates of the 20th NYSM.57

Grant now came to have an even keener appreciation for Sharpe’s services, and soon the colonel was spending half his time at the general-in-chief’s headquarters. Grant knew that doubt always remained even with the best intelligence, but his genius was that he was able not only to deal with ambiguity but to profit from it. He valued intelligence but would never be paralyzed by the lack of its perfection. Sharpe found Grant’s command style more than congenial, epitomized in his most famous statement, “The art of war is simple enough. Find out where your enemy is. Get at him as soon as you can. Strike him as hard as you can and as often as you can, and keep moving on.”58 Grant quickly became aware of how vital Sharpe was for executing the first part of that definition—“Find out where your enemy is.”

By this time, Sharpe was briefing Grant on almost a daily basis at his City Point headquarters and had drawn the all-source net back into his hands. When the armies had settled down to the grinding siege of Petersburg, beginning on July 9, Babcock was able to perfect his enemy order-of-battle by the careful coordination of excellent Signal Corps observation, the interrogation of deserters, and the breaking of the latest Confederate signal flag alphabet. Had anyone in the chain of command given thought to rebuilding the defunct Balloon Corps, it would have been a powerful addition to intelligence collection the flat terrain around Richmond and Petersburg.

Immediately on assuming duties at City Point, Sharpe focused on detecting transfers of forces between Lee’s army at Petersburg and the Valley. His timing was right on. In late July Early made another raid north and burnt Chambersburg in Pennsylvania in retaliation for Union depredations in the South. The need to protect Washington and the opportunity to disrupt the interior lines that allowed Lee to shuffle his troops back and forth became obvious. Sharpe realized he needed more than his core BMI staff. He needed more scouts and spies. At the same time, Grant gave him two missions. The first was to coordinate intelligence operations between his headquarters and the Army of the James south of Richmond in order to keep track of Early. The second was to “get into Richmond.” Patrick did his best to help Sharpe with these missions by seeing him off to City Point on July 21 to set up his new offices there and at Bermuda Hundred with Butler’s headquarters, and about “sending off Scouts etc[.] in the direction of Orange Court House, to watch Early and get into Richmond.”59

Sharpe partially accomplished the first mission by sending Babcock to Washington to set up a system to keep track of the main railroads that Early would have to use to shuttle troops back and forth. Sharpe had proposed this idea to Meade who had rejected it earlier, but Grant was more appreciative of this sort of imaginative initiative. Sharpe was able almost immediately after relocating to City Point to begin organizing this collection system. Because Grant’s forces around Richmond did not have direct overland contact with this area of Virginia, this mission had to be controlled from the War Department in Washington. Babcock organized three of his spies living west of Fredericksburg, including old Isaac Silver, to travel to the railroad depots conveniently near their homes to monitor movement. Silver had moved from his ruined farm above Fredericksburg to a place below the town and near the railroad terminus. It is a tribute to Silver’s patriotism that he continued to work as actively as an agent even after the devastation of his farm by Sheridan’s cavalry.

The Battle of Jerusalem Plank Road, June 22, 1864.

Sharpe sent the scouts Dodd, McCord, Phil Carney, and S. McGee, among others. They were based in Fredericksburg and would meet the agents several times a week. Tugs were provided to shuttle them with their information to Washington from which Babcock would send their information to Grant and Sharpe. Once this new network was in place, Babcock returned to Petersburg, leaving the direction and coordination of the scouts in the hands of one of Grant’s assistant adjutant generals in Washington, Lt. George K. Leet, who in effect became a member of Sharpe’s team. He was responsible for intelligence operations between Washington and Richmond, in which Confederate authority had been reintroduced after the Army of the Potomac had passed and established its communications by the James River instead of overland. Leet had the authority to send the reports of these scouts to any command that required the information. By September, the hidden southern agents were supplying information “as often as five times in two weeks.”60

Sharpe now essentially operated a branch BMI office, with Butler’s Army of the James under the control of Lieurenant Manning. He was assisted by Lieutenant Davenport, Butler’s military secretary, who would become an important element of the effort. Butler’s enthusiastic support of this office would ease the coordination of intelligence considerably. McEntee would continue to operate out of Meade’s headquarters south of Petersburg, and most of their reporting concentrated on the enemy opposing the Army of the Potomac. No matter where they worked, the members of the BMI were constantly exchanging information and coordinating their analysis through Sharpe by telegram over the efficient lines set up by the Signal Corps. Davenport, Babcock, and McEntee concentrated on the enemy’s order-of-battle as Sharpe drew all the collection sources together.

To accomplish the second mission Sharpe had given Sergeant Knight instructions on “establishing daily communications between the Capital of the Confederacy and Gen. Grant’s Headquarters at City Point.” Two days after a scout group had set up at City Point, Knight was ready to try. Sharpe sent him his own orderly, a man named Powers, a native of Richmond and Unionist, thinking his knowledge of the Richmond area would be useful. Upon questioning him, Knight learned that Powers had fled Richmond to escape Confederate military service and had been secreted out of the city by another Unionist named Alexander Myers. The more Powers described Myers, the more Knight found him a potentially valuable contact. Myers was a New Jersey native who had spent time in jail in North Carolina for his Unionist sympathies but had moved to Richmond where he found a job with the Quartermaster Department. He had a roving commission to move anywhere about the state to confiscate any Union military property that had been left behind. Apparently, the Confederate Secret Service was behind on its background investigations.

Powers, it seemed, had also been a clerk for John Van Lew, which instantly reminded Knight of the conversation he’d had with him before the Overland Campaign, to the effect that his mother and sister would be able and willing provide a great deal of useful information if contacted. The Van Lew ladies were also known to Sharpe through Major General Butler, but Butler had apparently not been able to reestablish reliable contact with the women. The quality of information they had provided convinced him that they were the key to penetrating Richmond. He now gave Knight a letter for Elizabeth Van Lew. He was to give it to Myers, whom he hoped would deliver it. Powers, unfortunately, refused point blank to return to Confederate territory to guide the scouts to Myers. Knight would have to settle for closely questioning Powers about the terrain across the James from City Point. A steamer put Knight and scout Anson B. Carney ashore at night. Sharpe’s bureau had an unquestioned priority for the use of any vessel they required. They crept inland, and slipped through enemy pickets, careful to leave no hint of their passage. Knight had been duly impressed by Sharpe’s inflexible instructions to that effect that they “could neither kill nor take prisoners on night expeditions.” There must be no trace of their comings and goings.

They came to a house. Knight knocked on the door and identified himself as Captain Phillips of the 5th North Carolina Cavalry but was told by a woman that she would not open it at night but to come to the back of the house where they could speak through a window. He explained that he was looking for Myers on official business; she knew Myers, who was scheduled to come by and drop off a barrel of flour. The woman was joined by another and both obviously had Southern sympathies. The second woman was suspicious why the authorities in Richmond would send out an officer who knew nothing of the area to look for Myers and who had passed through the pickets outside.

Knight went right into action, employing the cool effrontery that was the scout’s best weapon:

Putting on all the dignity I could muster, with as much hauteur as I could possibly assume, I sternly said: “Mrs. Slater, has not the war been going on nearly four years, and have you not learned by this time that a soldier, when he receives an order from his superior officer, has but one thing to do, obey it? Now, I can’t say why Myers is wanted in Richmond, what he had done, or why he is wanted. I know nothing. I simply know that Gen. Winder, the Provost-Marshal of the Confederacy, ordered me about sundown to come down here and bring Myers to Richmond with me. Why I was sent on the errand I know not. Why he did not send some one who knew the country better than we do it is impossible for me to say. Your insinuations as to how we passed the pickets lead me to suspect you don’t believe what I have told you. I supposed we were talking to a woman with intelligence enough to know that an officer of Gen. Winder’s rank and ability would not send a man off on an errand of that kind without papers that would pass him anywhere, and that is what I have got. Perhaps I had better show them to you, and possibly, after seeing them you will believe I have not been telling you a pack of lies. Sergeant, have you a match?

The woman’s suspicions were quashed. Knight had the women raise their right hands to pledge that they would reveal nothing of this conversation to anyone, including Myers. Twenty minutes after Knight and Carney had left Myers arrived. The women rushed down the walkway to the gate to tell him to “Look out for Capt. Phillips of the 5th NC Cav.” who was out to find him.61

Their steamer was waiting to take them back to City Point before dawn. That morning Knight briefed Sharpe who concluded that the proper guide for that area would be a local black man. He had found that they knew the areas they had lived in intimately. He issued orders allowing Knight to acquire the services of any black man native of Charles County and working for the Quartermaster at Bermuda Hundred. He found such a man in a free black named Lightfoot Charles. As with Powers, no inducement could get Charles to cross the river back into “Rebeldom.” But with much cajoling and encouragement, he eventually and reluctantly agreed. Knight could have saved all the effort, for Charles turned out to be a very bad guide in the night, but in his defense, he had warned them that “it’s rather a blind place to find, in fact.”

During their next attempt, it was clear they were lost with Lightfoot as a guide, but what Sharpe called Knight’s “topographical instinct” got them back to the wharf and waiting steamer. That instinct, Knight explained, was that he “was like a mule—could find my way to the place where I was last fed.” Charles had at least provided one service by identifying the house of a Union sympathizer named Hill, an English immigrant.