Chapter One

Mobilizing for War

In January 1861 the commandant of the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Captain Samuel Francis Du Pont, wrote an anguished letter to his longtime friend Commander Andrew Hull Foote, head of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Fifty-seven and fifty-four years old, respectively, Du Pont and Foote had served in the U.S. Navy since they were teenagers. They were destined to become two of the first five admirals in American history a year and a half later. Descendant of a French royalist who had emigrated to America during the French Revolution, Du Pont was a tall and imposing figure with ramrod-straight posture and luxuriant mutton-chop whiskers. Although he resided in the slave state of Delaware, Du Pont had no time for secessionists who were at that moment taking seven states out of the Union and talking about uniting all fifteen slave states in a new nation. “What has made me most sick at heart,” he wrote, “is to see the resignations from the Navy” of officers from Southern states. “If I feel sore at these resignations, what should a decent man feel at the doings in the Pensacola Navy Yard?” On January 12 Captain James Armstrong, commandant of the Pensacola Navy Yard, had surrendered this facility and Fort Barrancas to militia from Florida and Alabama without firing a shot. A native of Kentucky and one of the most senior captains in the navy with fifty-one years of service, Armstrong feared that an attempt to defend the navy yard might start a civil war. For this decision he was subsequently tried by court-martial and suspended for five years, ending his career in disgrace. His act brought contempt and shame to the navy, wrote Du Pont. “I stick by the flag and the national government,” he declared, “whether my state do or not.”1

There was no question where Foote’s allegiance lay. A Connecticut Yankee, devout Christian, and temperance and antislavery advocate, he fervently believed that patriotism was next only to godliness. Concerning another high-ranking naval officer, however, there were initially some doubts. Captain David Glasgow Farragut had served fifty of his fifty-nine years in the U.S. Navy when the state he called home, Virginia, contemplated secession in 1861. Farragut had been born in Tennessee and was married to a Virginian. After his first wife died, he married another Virginia woman. He had a brother in New Orleans and a sister in Mississippi. “God forbid I should ever have to raise my hand against the South,” he said to friends in Virginia as the sectional conflict heated up.2

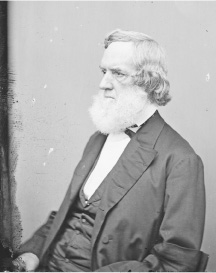

Captain Samuel Francis Du Pont. This photograph probably dates from the late 1850s. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Many of Farragut’s acquaintances expected him to cast his lot with the new Confederate nation. But he had served at sea under the American flag in the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War, and he was not about to abandon that flag in 1861. When the new president, Abraham Lincoln, called up the militia after the Confederates attacked Fort Sumter, Farragut expressed approval of his action. His Virginia friends told him that anyone holding this opinion could not live in Norfolk. “Well, then,” Farragut replied, “I can live somewhere else.” He decided to move to New York. “This act of mine may cause years of separation from your family,” he told his wife, “so you must decide quickly whether you will go north or remain here.” She resolved to go with him. As they prepared to leave, the thin-lipped captain offered a few parting words to his Virginia neighbors: “You fellows will catch the devil before you get through with this business.” When Virginia seceded and its militia seized the Norfolk Navy Yard, Farragut told his brother: “I found things were growing worse . . . and told her [his wife] she must go at once. We all packed up in 2 hours & left on the evening steamer.”3 Farragut no doubt remembered this hurried departure when his victorious fleet steamed into New Orleans almost exactly a year later.

One of Farragut’s Southern friends made the same choice he had made. Born in South Carolina, Percival Drayton was one of the most promising officers in the navy when his native state seceded on December 20, 1860. Although several of his numerous relatives fought for the Confederacy—including his older brother Thomas, a low-country planter and Confederate general—Percival never hesitated. “The whole conduct of the South has destroyed the little sympathy I once had for them,” he wrote a month after South Carolinians fired on Fort Sumter. “A country can recover from anything except dismemberment. I hope this war will be carried on until any party advocating so suicidal a course is crushed out.” Drayton became one of the best fighting captains in the Union navy, serving with Du Pont in the capture of Port Royal and the attack on Charleston and with Farragut as fleet captain at Mobile Bay. While commanding the steam sloop USS Pawnee in operations along the South Carolina coast in November 1861, Drayton wrote to a friend in New York: “To think of my pitching in here right into such a nest of my relations . . . is very hard but I cannot exactly see the difference between their fighting against me and I against them except that their cause is as unholy a one as the world has ever seen and mine is just the reverse.”4

Drayton’s and Farragut’s loyalty to the Union was not typical of officers from Confederate states. Some 259 of them resigned or were dismissed from the navy. Most went into the new Confederate navy. One hundred and forty of them had held the top three ranks in the U.S. Navy: thirteen captains, thirty-three commanders, and ninety-four lieutenants. Forty Southern officers of these ranks, mostly from border states that did not secede, remained in the Union navy.5

One of those who went South became the first—and, until almost the end of the war, the only—admiral in the Confederate navy: Franklin Buchanan of Maryland. He was a veteran of forty-five years in the U.S. Navy, the first superintendent of the Naval Academy when it was established in 1845, second in command of Matthew Perry’s famous expedition to Japan (1852–54), and commandant of the Washington Navy Yard when the Civil War began. Three days after a secessionist mob in Baltimore attacked the 6th Massachusetts Militia on its way through the city to Washington on April 19, Buchanan entered the office of Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. The two men were a study in contrasts. Buchanan was smooth-shaven with a high forehead and receding hairline, thin lips turned down in a perpetual frown, and an imperious manner of command. Welles’s naval experience was limited to a two-year stint as the civilian head of the Bureau of Provisions and Clothing during the Mexican-American War. A long career as a political journalist in Connecticut had given little promise of the resourceful administrative capacity he would demonstrate as wartime secretary of the navy. The wig he wore with brown curly hair down almost to his shoulders contrasted oddly with his long white beard, which caused President Lincoln to refer to him fondly as “Father Neptune.” The president had announced a blockade of Confederate ports five days earlier, and Welles needed all the help he could get from experienced officers like Buchanan to make it work. But Buchanan had come to tender his resignation from the navy. The riot in Baltimore convinced him that Maryland would secede and join the Confederacy. It was his duty to go with his state. Welles expressed his regrets, but he did not try to talk Buchanan out of resigning. “Every man has to judge for himself,” acknowledged the secretary.

Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

As the days went by and Maryland did not secede, Buchanan had second thoughts. Perhaps he had acted rashly. He tried to withdraw his resignation. But Welles wanted no sunshine patriots in his navy. Like Du Pont, he was angry at officers who had resigned to fight against their country. To Buchanan’s request to retract his resignation, the secretary replied icily: “By direction of the president, your name has been stricken from the rolls of the Navy.”6

Welles had been soured by an experience three weeks earlier concerning another senior Southern officer, Captain Samuel Barron of Virginia. As Welles sat eating dinner at the Willard Hotel on the evening of April 1 (his wife and family had not yet joined him in Washington), he was startled to receive a packet of papers from John Nicolay, one of Lincoln’s private secretaries. Welles was even more astonished when he read a series of orders signed by the president that reassigned Captain Silas Stringham from his post as Welles’s assistant to select officers for various commands and replaced him with Captain Barron. Welles rose quickly from his unfinished dinner and rushed to the White House. As Father Neptune burst into Lincoln’s office brandishing the orders like a trident, Lincoln looked up apprehensively. “What have I done wrong?” he asked. Welles showed him the orders, which Lincoln sheepishly admitted he had signed without reading carefully. They had been prepared under Secretary of State William H. Seward’s supervision, he said, and the president was so distracted by a dozen other problems that he had mistakenly trusted Seward’s recommendation.

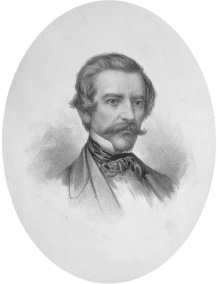

Commodore Franklin Buchanan of the Confederate navy. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

This was not the first nor the last time Seward meddled with matters outside his department. Lincoln told Welles to ignore the orders. Both men recognized that this incident was part of Seward’s effort to keep the Upper South states, especially Virginia, from seceding. Still under the erroneous impression that he was the “premier” of the administration, Seward naively believed that by giving Barron authority over personnel matters in the Navy Department, he would cement Barron’s—and Virginia’s—loyalty to the Union. Welles considered Barron a secessionist—the last man to be trusted with personnel assignments. He was right. Unknown to Lincoln or Welles at the time, Barron had already been appointed a captain in the Confederate navy—which as yet scarcely existed—and would soon resign to go South.7

Seward’s fingerprints were all over another scheme to interfere with the navy as part of his increasingly desperate intrigues to conciliate the South by avoiding confrontation with the Confederacy at Fort Sumter. The situation at that potential tinderbox in Charleston Harbor had remained tense since South Carolina artillery in January had turned back the chartered ship Star of the West, which was carrying reinforcements to the fort. An uneasy truce likewise existed between the Florida militia that seized Pensacola and U.S. soldiers who continued to hold Fort Pickens across the entrance to Pensacola Bay. The first effort by the new Lincoln administration to reinforce Fort Pickens had foundered because the orders to the captain of the USS Brooklyn to land the troops were signed by the army’s adjutant general and not by anyone in the Navy Department. Welles immediately signed and sent new orders, which were successfully carried out on April 14.8

In the meantime, however, Lincoln had also decided to resupply the U.S. garrison at Fort Sumter, even at the risk of provoking the Confederates to fire on the fort and supply ships. Seward opposed this decision. He continued to insist that a confrontation at Fort Sumter would start a war and drive the Upper South into secession. He also maintained that withdrawal of troops from the fort would encourage Unionists in the South (whose numbers he vastly overestimated) to regain influence there. Lincoln feared that withdrawal from Fort Sumter, which had become the master symbol of divided sovereignty, would undermine Southern Unionism by implicitly recognizing Confederate legitimacy.

Lincoln’s Postmaster General, Montgomery Blair, thought so too. He introduced Lincoln to his brother-in-law Gustavus V. Fox, a former navy lieutenant, who suggested a way to run supplies and troops into Fort Sumter at night with shallow-draft tugboats. With his rotund figure and high, balding forehead, Fox did not look much like a dashing naval officer. But he had a can-do manner that convinced Lincoln—who was already weary of advisers who told him that something or other could not be done—that this thing could be done. He told Fox to work with Welles to assemble the supplies and warships to escort the troop transports and tugs to Charleston.9

Only three warships and the Treasury Department’s revenue cutter Harriet Lane were available for the mission. The largest warship was the USS Powhatan, a 2,400-ton sidewheel steamer carrying ten big guns. It became the centerpiece of a monumental mix-up that illustrated the disarray of the Lincoln administration in the midst of this crisis. On April 1 Welles ordered the Brooklyn Navy Yard to ready the Powhatan for the Fort Sumter expedition. On the same date, Seward wrote his infamous memorandum to the president suggesting that he might reunite the nation by provoking a war with France or Spain and urging him to reinforce Fort Pickens as an assertion of authority but abandon Fort Sumter as a gesture of conciliation. Lincoln in effect gently slapped Seward’s wrist for this effrontery. But on that day Seward also engineered the order placing Samuel Barron in charge of assigning naval personnel, which Welles got Lincoln to rescind. And Seward promulgated yet another dispatch on April 1 and got Lincoln to sign it; this one ordered the commander of the Brooklyn Navy Yard to prepare the Powhatan for an expedition to reinforce Fort Pickens. “She is bound on secret service,” directed Seward, “and you will under no circumstances communicate to the Navy Department the fact that she is fitting out.”10

Captain Foote, head of the navy yard, must have scratched his head when he received these two contradictory orders, the first signed by the secretary of the navy and the other by the president. Was one of them an April Fool’s joke? Foote and Welles had been friends since their schoolboy days together in Connecticut forty years earlier. Despite the admonition to keep the second order secret from Welles, Foote sent a cryptic telegram questioning it.11 On April 5 Welles finally realized what was going on. He confronted Seward, and both rushed to the White House. Although it was almost midnight, Lincoln was still awake. When he understood the nature of this messy contretemps, he ruefully admitted his responsibility and told Seward to send a wire to the navy yard to restore the Powhatan to the Fort Sumter expedition. Seward did so, but whether intentionally or not, he signed the telegram simply “Seward” without adding “By order of the President.” When it reached Brooklyn, the Powhatan had already left under command of Lieutenant David D. Porter. A fast tug caught up with Porter before he reached the open sea, but when he read the telegram signed by Seward, he refused to obey it, claiming that the earlier order signed by Lincoln took precedence. The Powhatan continued to Fort Pickens, which had already been reinforced by the time it arrived.12

In the end, the Powhatan’s absence from the Fort Sumter expedition made no difference to the outcome. The nature of this operation had changed since Fox first suggested it. Lincoln realized that an effort to reinforce Sumter with 200 soldiers was likely to provoke shooting in which the North might appear to be the aggressor. So he decided to separate the issues of reinforcement and resupply and to notify the governor of South Carolina of his intentions. On April 6 he sent a messenger to tell Governor Francis Pickens to “expect an attempt will be made to supply Fort-Sumpter [a common misspelling] with provisions only; and if such attempt be not resisted, no effort to throw in men, arms, or ammunition, will be made, without further notice, or in case of an attack on the fort.”13 The governor forwarded this message to Brigadier General Pierre G. T. Beauregard, commander of the Confederate forces ringing Charleston Harbor. Beauregard immediately relayed it to President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet in Montgomery.

Lincoln had deftly put Davis on the spot. If he allowed the supplies to go in, the Federal presence at Fort Sumter would remain and the Confederate claim of sovereignty would lose credibility. But if Confederate guns made an unprovoked attack on the fort or on the boats bringing “food for hungry men,” Davis would stand convicted of starting a war, which would unite the North and perhaps divide the Southern states. Davis did not hesitate. He ordered Beauregard to give notice and to open fire if Major Robert Anderson, commander of the eighty-odd soldiers in Fort Sumter, did not evacuate. Fox and his fleet were delayed and scattered by a storm; the tugs had to put into a shelter port and never arrived at all. By the time the rest of the fleet rendezvoused off the bar at the entrance to Charleston Harbor, Fort Sumter was under attack and the seas were too rough for the ships to get over the bar. The fort lowered the American flag in surrender on April 14. And the war came.

It came in such a way as to unite a previously divided Northern people in support of “putting down the rebellion.” And Lincoln’s call for militia to suppress the insurrection caused four more Upper South states to secede—but significantly, not the border slave states of Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, and Delaware.

Fox was dejected by the failure of his mission and angry about the diversion of the Powhatan. Lincoln consoled him. “You and I both anticipated that the cause of the country would be advanced by making the attempt to provision Fort-Sumpter, even if it should fail,” he wrote to Fox on May 1. “It is no small consolation now to feel that our anticipation is justified by the result.” Lincoln assured Fox that “the qualities you developed in the effort, have greatly heightened you, in my estimation. For a daring and dangerous enterprise, of a similar character, you would, to-day, be the man, of all my acquaintances, whom I should select.”14

A week later, Lincoln ordered Welles to cut any red tape that might prevent Fox’s appointment as chief clerk of the Navy Department. “He is a live man,” Lincoln wrote, “whose services we cannot well dispense with.”15 Welles appointed Fox that very day. In July Congress created the position of assistant secretary of the navy, and Lincoln promoted Fox to that job. In effect, Fox exercised the function of chief of naval operations for the next four years. Although his brusque manner and tendency to make snap judgments rubbed some naval officers the wrong way—Farragut once complained that he “assumes too much and presumes too much”—Fox and Welles worked well together and imparted great energy into an institution burdened with a lot of deadwood at the beginning of the war. In June 1862 Samuel F. Du Pont told his wife, who did not like Fox, that “all the past administrations of the Navy put together can in no manner compare with this last year in energy, development, and power.” Fox could be irritating, acknowledged Du Pont: “I am often faulted by him in details, very provoking it is true, but these sink when I reflect that we have two hundred ships of war with rifle cannon now on the ocean—when in March [April] ’61 we had not one within reach to save the Norfolk Navy Yard.”16

WITHIN A WEEK OF THE attack on Fort Sumter, Presidents Davis and Lincoln issued proclamations that shaped significant elements of their respective naval strategies. On April 17 Davis offered letters of marque to private ships authorizing them to capture American-flagged merchant vessels. As the weaker naval power in two wars against Britain, the United States had commissioned swarms of privateers to prey on British ships and force the Royal Navy to divert its warships to commerce protection. Now the Confederacy proposed to pursue the same strategy against the United States. In a proclamation issued two days later announcing a blockade of Confederate ports, Lincoln declared that captured privateers would be tried for piracy.17

Lincoln’s proclamation contained an internal inconsistency. The definition of privateers as pirates was grounded in the theory that the Confederacy was not a nation but an association of insurrectionists—“rebels” in the common terminology. At the same time, however, the declaration of a blockade seemed to recognize the legitimacy of the Confederacy, for blockades were an instrument of war between nations. For that reason, some Northerners—most notably Secretary of the Navy Welles—urged the president simply to announce a closure of ports in the rebellious states. To enforce such closure, however, would require warships stationed off these ports, which amounted to a blockade. The British government warned the United States that it would not respect a proclamation closing certain ports to international trade. The British minister to the United States, Lord Lyons, pointed out that a declaration closing Southern ports would cause foreign powers to recognize the Confederacy as controlling these ports de jure, as they already controlled them de facto, so they could trade freely with the Confederacy.18 Having relied on blockades in their own numerous wars, however, Britain would respect a blockade imposed under international law. Lincoln took these points seriously and decided against the closure option. In effect, by imposing a blockade, the United States treated the Confederacy as a belligerent power but not as a nation.

That compromise was not forged immediately, however, and did not resolve the question of the status of privateers. Two dozen of them soon swooped out along the Atlantic coast and the Gulf of Mexico. They captured at least twenty-seven prizes, mainly in the spring and summer of 1861.19 The most notorious and successful privateer was the brig Jefferson Davis (a former slave ship), which captured eight prizes in July and August. One of them was the schooner S. J. Waring, whose cook and steward was William Tillman, a free Negro. A prize crew of five men took the S. J. Waring toward the Jefferson Davis’s home port of Charleston. Tillman and two other crew members of the Waring remained on board. Certain that he would be sold into slavery when the Waring reached Charleston, Tillman killed the sleeping prize master and two sailors on the night of July 16–17. He released the two Yankee crewmen, and they sailed the recaptured prize back to New York, where Tillman was hailed as one of the war’s first heroes. “To this colored man was the nation indebted for the first vindication of its honor at sea,” declared the New York Tribune. “It goes far to console us for the sad reverse of our arms at Bull Run.”20

The Union navy recaptured other prizes and also captured the crew of the privateer Petrel in July 1861. In a letter to Lincoln on July 16, President Jefferson Davis warned that he would order the execution of a Union prisoner of war for each member of a privateer crew executed for piracy.21 The U.S. government nevertheless proceeded to try the Petrel crew in federal court in Philadelphia. Four of them were convicted. Several captured crewmen of the Jefferson Davis were also convicted. True to his word, President Davis ordered lots drawn by Union prisoners, with the losers (including a grandson of Paul Revere) to be hanged if the privateers suffered that fate. The Lincoln administration backed down in February 1862 and thereafter treated such captives as prisoners of war.22

By that time the privateers had virtually disappeared from the seas. Other nations refused to admit prizes to their ports, and the tightening Union blockade made it too difficult to bring them into Confederate ports. The future of Confederate commerce raiding belonged to naval cruisers, fast and well-armed steamers commanded by Confederate officers. They burned most of their captures rather than seizing them as prizes. Most of these cruisers were built or bought abroad, but the first one, the CSS Sumter, was a merchant ship purchased in New Orleans at the beginning of the war and converted into a warship. Like other seagoing steamers on both sides in the Civil War, the Sumter carried sails (a bark rig in her case) for long-distance cruising and fired up the boilers when needed for speed and maneuverability, or in adverse conditions of wind and weather.

The Sumter’s commander was Raphael Semmes, who became the most famous of all Confederate sea captains. A veteran of thirty-five years in the U.S. Navy, he resigned in 1861 when his home state of Alabama seceded. A handsome, dashing figure with a waxed handlebar mustache and small goatee, Semmes was unexcelled in seamanship in both the old navy and his new one. He was also a strong proslavery partisan. During his wartime cruises in the Caribbean and along the Brazilian coast, he often noted in his journal that the Confederacy was fighting not only for the defense of slavery in the South but also in Cuba and Brazil, the only other Western hemisphere societies where it still existed. To the governor of Martinique “I explained the true issue of the war, to wit, an abolition crusade against our slave property.” He told the president of a Brazilian province in September 1861 that “this war was in fact a war as much in behalf of Brazil as ourselves; that we were fighting the first battle in favor of slavery, and that if we were beaten in this contest, Brazil would be the next one to be assailed by Yankee and English propagandists.”23

In mid-June 1861 Semmes completed his preparations for the Sumter’s cruise to hunt Yankee merchantmen and dropped down the Mississippi to wait for a chance to evade the Union warships guarding each of the passes into the Gulf of Mexico. On June 30 he learned that the USS Brooklyn had gone off after a suspected blockade-runner. Semmes seized the opportunity and steamed into the Gulf at top speed. The returning Brooklyn took up the chase. The weight of her armament outgunned the Sumter’s by three to one. Black smoke poured from the funnels of both ships as they built up maximum steam pressure. They also set all sails for greater speed. The Sumter could sail closer to the wind and soon left the larger Brooklyn behind.

Captain Raphael Semmes of the Confederate navy. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Two days later, the Sumter captured her first prize, the sailing vessel Golden Rocket. She “made a beautiful bonfire,” Semmes wrote, “and we did not enjoy the spectacle less because she was from the black Republican State of Maine.”24 During the next four days, the Sumter captured seven more American merchant vessels and tried to take them to Cuba as prizes. The Spanish government, having declared its neutrality in the American Civil War, interned them instead. Semmes departed in disgust and captured several more ships over the next few months. He burned them if both ship and cargo were American, and he bonded them (the value of the ship to be paid to the Confederacy after the war) if the ship’s papers showed the cargo to belong to neutrals.

Semmes made effective use of a time-honored ruse in these captures. The Sumter flew the American flag as it approached similarly flagged merchant vessels. After ordering the ship hove to (they were all sailing vessels), Semmes ran up the Confederate flag as its guns bore on the hapless merchantman. By January 18, 1862, when the Sumter put into Gibraltar for repairs, she had captured eighteen ships altogether. Union warships blockaded the Sumter at Gibraltar. Semmes finally left her there and departed for England, from where he went on to perform even more destructive deeds as captain of the CSS Alabama. A Liverpool merchant bought the Sumter and turned her into a blockade-runner named Gibraltar.25

The Confederate strategy of diverting blockade ships into the pursuit of privateers and commerce raiders was working. From May 1861 onward, petitions poured into the Navy Department from shipping firms, bankers, and insurance companies demanding protection for merchant vessels. Newspaper editorials berated Welles for the navy’s failure to catch the “pirates.”26 Welles was doing his best. Orders went out to a dozen or more navy captains to hunt down privateers and the Sumter. These instructions to Commander James S. Palmer of the USS Iroquois were typical of such orders: “You will continue in pursuit of the Sumter until you learn positively she has been captured or destroyed. You will then remain in the West Indies in search of other privateers and for the protection of American interests until further ordered.”27

The ocean is a big place, however, and a single ship can be as hard to find as the proverbial needle in a haystack. Even the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea cover thousands of square miles where as skillful a sailor as Semmes could evade his pursuers. American consuls in several countries tried to gain information about the Sumter’s location and pass it along to naval commanders. Union warships would go to where the raider was last reported and discover that she had left three days earlier for an unknown destination. The captain’s clerk on the Iroquois expressed the frustration of that ship’s crew: “We still keep going after the Sumpter and she still escapes us.” On August 13, 1861, Lieutenant David D. Porter of the Powhatan reported to Welles that the Sumter was said to be short of coal, so Semmes “is in a position now where he can’t escape, if properly looked after, at Porto Cabello.” Porter kept up the futile pursuit, writing six weeks later that “I have chased her from point to point.” At each place she was reported to have been, there was no sign of her. “I had to speculate on the course she would likely pursue,” he admitted in frustration. “I can form no idea where the Sumter is at this time.”28

IN THESE EARLY MONTHS of the war, Confederate efforts to wreak havoc on the American merchant marine and deflect blockade ships seemed more successful than the blockade itself. But the potential for a blockade to constrict the Confederate war effort was much greater than the raiders’ potential to damage the Northern economy. As an agricultural society with little industry, the Confederacy was heavily dependent on imports of war matériel and export of cotton to pay for it. An effective blockade would do serious damage to this process.

The key word here, however, is “effective.” After the secession of Virginia and the imminent departure of North Carolina, Lincoln extended the blockade to these states on April 27, 1861.29 To patrol a coastline of 3,500 miles from Virginia to Texas with 189 harbors and coves where cargo could be landed was a herculean task. Only a dozen of these harbors had railroad connections to the interior, but imposing an effective blockade on just these ports would require large numbers of ships to cover the multiple channels and rivers and inland waterways radiating from or connecting several of them.

At the war’s beginning, the Union navy did not have enough ships on hand to do more than show the flag at a few of these waterways. In April 1861 the navy had only a dozen warships in American waters, five of them sailing vessels that could perhaps catch other sailing ships trying to evade the blockade but were of little use against steamers. Twenty-six other warships—seventeen of them steam-powered—were scattered around the world from the Mediterranean Sea to the coasts of Africa and China. Of the navy’s six new steam frigates and thirteen new steam sloops constructed since 1855 in a major naval buildup, only two of the sloops and none of the frigates were operational in home waters. Five of the six frigates, in fact, were laid up at navy yards for repairs.30

Orders went out to most of the ships in foreign waters to return home. Welles also embarked on a crash program to buy or charter as many merchant steamers, passenger steamers, and even New York ferryboats as he could that were capable of conversion into armed vessels for blockade duty. His purchasing agent for many of these ships was George D. Morgan, a New York businessman who also happened to be Welles’s brother-in-law. They were embarrassed by charges of nepotism. But Morgan was an honest and savvy agent. Although he earned $70,000 in commissions for the eventual total of eighty-nine ships that he purchased, the navy got them for very reasonable prices. The department also bought eighty-seven other vessels from various sources in 1861. In addition, Welles contracted for the building of twenty-three new ships of about 500 tons each (the famous “ninety-day gunboats”) plus fourteen screw sloops and twelve sidewheelers that began to come on line in the fall of 1861. The British minister to the United States, Lord Lyons, was impressed. He informed Foreign Secretary Lord Russell in May 1861 that “the greatest activity prevails in the United States Navy yards. Vessels are being fitted out with the utmost speed, and many have been purchased, with a view to establish the blockade effectively.”31

The naval buildup included men as well as ships. On the eve of the war, the U.S. Navy numbered about 7,600 enlisted men and 1,200 officers of all ranks from ensign to captain. Welles persuaded Lincoln to authorize by executive order the recruitment of an additional 18,000 men for terms of one to three years. The president announced this action in a proclamation dated May 3, 1861. Many of these men would be drawn from the merchant marine and would enter the service as able seamen or ordinary seamen, depending on their level of skill and experience. Most, however, enlisted with little or no seafaring experience and were rated as landsmen or “boys” (seventeen or younger). Within two months, the Union navy had expanded to 13,000 men plus about 2,000 officers. By December 1862 the total number of naval personnel had grown to about 28,000 sailors and officers plus 12,000 mechanics and laborers in navy yards. In early 1865 the Union navy reached its maximum strength of 51,500 men and 16,880 mechanics and laborers. The total number of Union sailors and officers during the war as a whole was 101,207 because many sailors whose enlistment terms expired did not reenlist. The Confederate navy reached the peak of its strength at the end of 1864 with 4,966 enlisted men and officers. The Confederate total for the entire war is unknown, but because reenlistment was mandatory, that number probably exceeded the peak by only 1,000 or 2,000 men.32

Enlisted Union naval personnel differed in significant ways from volunteer soldiers: their average age was slightly older (twenty-six compared with twenty-five); they were more urban and working-class; 92 percent were from New England and mid-Atlantic states; and they were less literate, with a higher percentage of foreign-born (45 percent compared with 25 percent of soldiers) and of African Americans (about 17 percent compared with 9 percent in the army). Comparable data for Confederate sailors is not available, but nearly 20 percent of them were Irish-born—about four times the proportion of men in the Confederate army.33

While 97 percent of Union soldiers enlisted in the U.S. Volunteers rather than the Regular Army, there was no “volunteer” Union navy as such, so all sailors were part of the Regular U.S. Navy. But the officers who entered the navy from civilian life (almost all from the merchant marine) carried the designation of “acting” rather than a Regular rank: acting master, acting lieutenant, and so on. In December 1863 there were 1,977 “acting” officers from lieutenant (only sixty-eight of those) down to master’s mate and 469 Regular navy officers from admiral down to ensign. Even though several acting officers commanded gunboats or ships, they held no higher rank than acting lieutenant initially, though by January 1865 thirteen of them had been promoted to acting lieutenant commander.34 A much higher percentage of officers in the Union navy were long-term Regulars than in the army. They were also somewhat older and considerably more cosmopolitan, many having traveled all over the world in their decades of sea duty before 1861. Because there was no separate volunteer navy, and because of a greater social-class distance between officers and men in the navy than in the volunteer army regiments, the Union navy was more professional and disciplined than the army.

The Confederacy began the war with a substantial cadre of veteran officers who had resigned from the U.S. Navy, but it had almost no ships or enlisted men and only a tiny number of merchant mariners to draw on for experienced sailors. The South had important assets, however, in the high quality of many of its officers and in its secretary of the navy, Stephen R. Mallory. As a judge in Key West during the 1830s and 1840s, Mallory gained considerable maritime expertise while adjudicating the claims of shipowners and salvage wreckers in that notorious graveyard of ships. Elected to the U.S. Senate from Florida in 1851, he became chairman of the Naval Affairs Committee and helped steer through legislation to modernize the navy by the construction of powerful new steam frigates and sloops. A moderate who initially opposed secession, Mallory went with his state when Florida left the Union. A strong proponent of technological progress, he had informed himself about the new ironclad warships built by the British and French navies. He recognized that the fledgling Confederate navy could never match its enemy in quantity and firepower of traditional warships. From the outset, therefore, he focused on quality and innovation to challenge the Union blockade and to defend the Confederate coast.35

Mallory and his not-yet-existent navy got a huge windfall with the capture of the Gosport Navy Yard at Norfolk on April 20, 1861. Tensions had been building at the yard during the spring. Its commander, sixty-eight-year-old Commodore Charles S. McCauley, had been in the U.S. Navy since before Abraham Lincoln was born. McCauley was a native Philadelphian whose loyalty to the flag was undoubted, but he had achieved command of one of the navy’s largest facilities more by seniority than by ability. Ten ships were laid up for repairs at the yard. Most of them were old sailing vessels. The exception was the forty-gun USS Merrimack, one of the proud new steam frigates, whose faulty engines were being rebuilt. On April 10 Welles ordered McCauley to make sure the Merrimack was ready to be moved to Philadelphia if Virginia secessionists threatened to take over the yard. But Welles added what turned out to be a fatal qualification: “It is desirable that there should be no steps taken to give needless alarm. . . . Exercise your own judgment.”36

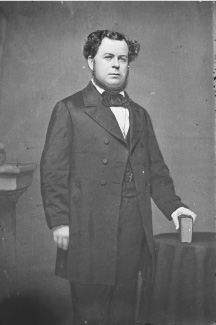

Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Most of McCauley’s subordinate officers were Virginians. They convinced him that any signs of moving the Merrimack would provoke the trigger-happy militia gathering near the facility. Welles seemed to realize that McCauley would prove weak and indecisive in the face of this pressure. On April 11 he sent unequivocal orders to “have the Merrimack prepared” to depart and on the 12th to have her “removed to the Philadelphia Navy Yard with the utmost dispatch.” McCauley replied that the engines would take four weeks to repair. Welles sent to Norfolk the navy’s chief engineer, Benjamin F. Isherwood, who had the engines in shape to get up steam and depart on April 17.37

That day, the Virginia convention voted to secede, and a thousand militia headed for the yard. Welles dispatched Captain Hiram Paulding with the USS Pawnee to stiffen McCauley’s backbone and get everything of value out of the yard that he could, including the Merrimack. But McCauley, now completely under the sway of younger officers—most of whom would soon resign and go over to the Confederacy—refused to let the Merrimack go. Instead, as the militia was poised to attack, he ordered all of the ships scuttled, “being satisfied,” as he later explained to Welles, “that with the small force under my command the yard was no longer tenable.” By the time Paulding arrived on the 20th the yard was ablaze and the ships scuttled except for the undamaged sailing frigate USS Cumberland, which Paulding had towed to safety. Finding the rest of the ships, including the Merrimack, beyond saving, Paulding ordered his men to finish the job in order to deny the rebels the dry dock, guns, ammunition, and anything else of value.38

They did not have time to carry out the destruction effectively. Virginians took over an undamaged dry dock, 1,200 cannon including fifty-two big Dahlgren smoothbores, the navy’s most advanced weapon, and thousands of shot and shells. Many of the guns and much of the ammunition were soon on their way to every corner of the South, where they would be placed in the dozens of new and existing forts the Confederacy was building and upgrading to defend its coast and rivers. Coming so soon after the fall of Fort Sumter, the loss of the Gosport Navy Yard was a dispiriting disaster for the Union navy and a terrific boost of morale for the Confederacy. And the most important consequence was not yet known. Although burned to the waterline, the Merrimack’s hull and even its balky engines had survived intact, ready to be reincarnated as the CSS Virginia.

The conversion of the Merrimack into a powerful ironclad was a key part of Stephen Mallory’s strategy of countering Northern naval superiority with Southern ingenuity. In June 1861 Mallory put one of the Confederacy’s brightest young naval officers, Lieutenant John Mercer Brooke, in charge of this conversion. “There is but one way of successfully combating the North,” wrote Brooke in an expression of his own as well as Mallory’s position, and “that is to avail ourselves of the means we possess and build proper vessels superior to those of the enemy. This we can do as the vessels of the enemy must be built for sea whilst ours need only to navigate the southern bays rivers etc.”39

It was true that Union blockading ships must have seagoing capability, and some of them were too large and deep-drafted to cross the bars and operate in Southern estuaries and rivers. But before the CSS Virginia and other new Confederate weapons could be ready, the traditional ships of the Union navy had scored major victories and Northern inventiveness had enabled new Union gunboats to dominate those Southern bays and rivers as well.