Chapter Five

The Confederacy Strikes Back

The CSS Virginia was not the first ironclad warship in history, nor in the Civil War, nor even in the Confederacy. The U.S. Congress had appropriated funds for an armored steam vessel in 1842, which became known as the “Stevens Battery” after its designer Robert Stevens, but it was never completed. The French had experimented with armored floating batteries in the Crimean War. Both Britain and France had operational ironclad warships by 1861. The cigar-shaped CSS Manassas with its one inch of iron sheathing attacked the USS Richmond downriver from New Orleans on October 12, 1861. The city class of ironclad river gunboats built by James B. Eads in 1861 first went into action at Fort Henry a month before the Virginia made its rendezvous with destiny at Hampton Roads on March 8, 1862. But the Virginia was the most famous of the Confederate ironclads. Its unique design became the prototype for twenty subsequent ironclads built or begun by the Confederacy. And its clash with the USS Monitor became the iconic naval battle of the war.

Stephen R. Mallory was the godfather of the Confederate ironclad program. “I regard the possession of an iron-plated ship as a matter of the first necessity,” he told the chairman of the Naval Affairs Committee in the provisional Confederate Congress in May 1861. Such a ship could “traverse the entire coast of the United States,” said Mallory, “prevent all blockades, and encounter, with a fair prospect of success, their entire navy. If to cope with them upon the sea we follow their example and build wooden ships, [we can never match them,] but inequality of numbers may be compensated by invulnerability.”1

Recognizing the Confederacy’s slender industrial capacity, Mallory initially hoped to buy or contract for the construction of ironclads in Europe. He sent Lieutenant James H. North to France and Britain for this purpose. Mallory embraced the fantasy that France might sell to the Confederacy the new ironclad Gloire, pride of its fleet. North was soon compelled to disabuse him of this expectation and to report that no ironclads were for sale in Europe.2 North later contracted for the building of an ironclad in a Glasgow shipyard, and other Confederate agents signed contracts for the construction of such vessels in England and France. But the long lead time to complete such ships meant that, even if the Confederacy could get them out of Europe, they might arrive too late to accomplish their purpose. And as things turned out, they never arrived at all, for the British and French governments decided to enforce their neutrality by preventing them from leaving.

The Confederacy was thus forced to rely on its own resources to construct ironclads. To build them from scratch would take a long time, and the Union navy was unlikely to wait. Lieutenant John M. Brooke, Naval Constructor John L. Porter, and Chief Engineer William P. Williamson came up with a solution. On June 23, 1861, they met with Mallory in Richmond and decided to build their ironclad on the hull of the USS Merrimack, burned to the waterline by the Federals when they had evacuated Norfolk in April. “This is our only chance,” said Brooke, “to get a suitable vessel in a short time.”3

Brooke provided the basic design, Porter supervised construction (the two men later quarreled publicly over which deserved the main credit), and Williamson rebuilt the faulty engines, whose defects were the reason the Merrimack was in for repairs when Norfolk fell. Work began in July but proceeded slowly and encountered frustrating delays because of shortages of iron, congestion on the railroads hauling materials, and the necessity of retooling at the Tredegar Iron Works to roll two layers of two-inch plates to cover the hull and casemate. Bolted onto the 263-foot hull, the casemate was 170 feet long and sloped at an angle of 36 degrees, which tests by Brooke showed was the best inflection to deflect shots fired by enemy warships. In these tests, Brooke also experimented with tallow and other kinds of grease on the iron plates to augment deflection. The casemate was pierced for three 9-inch Dahlgren smoothbore naval guns in each broadside plus two 7-inch rifles forward and two 6.4-inch rifles aft designed by Brooke. A seven-foot iron ram was bolted to the prow below the waterline. The Confederates christened their powerful though ungainly new warship the CSS Virginia. But Northerners and even many Southerners continued to call it the Merrimack (often spelled Merrimac).

There was no shortage of Union intelligence about the progress (or lack thereof) of the Virginia, despite efforts by Richmond newspapers to publish false information.4 Although the Confederates had gotten a head start, the Union navy soon embarked on its own saltwater ironclad program. At the request of Gideon Welles, in August 1861 the U.S. Congress appropriated funds to build three experimental ironclads. Welles created a three-man Ironclad Board of senior captains to choose the best designs. Would-be inventors submitted sixteen proposals. The board selected only two of them, one for a six-gun, 950-ton corvette with tumblehome sides protected by two and a half inches of interlocking iron plates that became the USS Galena and the other a 4,120-ton screw frigate of conventional design and twenty guns, sheathed with varying thicknesses of iron plating that became the USS New Ironsides.

The board expressed some doubts about the buoyancy of these vessels, however, so the prospective builder of the Galena, Cornelius Bushnell, decided to consult an expert on ship construction named John Ericsson. A Swedish-born naturalized citizen, Ericsson had invented the screw propeller and designed the first American screw frigate, the USS Princeton. When a cannon on the Princeton burst during trials in 1844, killing the secretaries of state and navy, some of the blame attached to Ericsson even though he had nothing to do with designing the gun. This experience soured him on the navy. For the next seventeen years, Ericsson designed commercial vessels and patented other innovations. In 1861 he did not submit a proposal to the Ironclad Board.

Ericsson assured Bushnell that the Galena would float and then asked if he would like to see an ironclad model that Ericsson himself had built. Bushnell was impressed by the unique features of the model. He persuaded Ericsson to let him show it to Welles and then to President Lincoln. Both were intrigued. Technological innovations fascinated Lincoln, who held a patent on a device to lift riverboats over shoals. At a meeting with the Ironclad Board on September 13, when members expressed skepticism about Ericsson’s design, Lincoln characteristically commented: “All I have to say is what the girl said when she put her foot in the stocking: ‘It strikes me there is something in it.’”5 But Captain Charles H. Davis upheld his reputation for conservatism in naval technology by ridiculing Ericsson’s model. In a parody of Exodus 20:4, he told Bushnell: “You may take the little thing home and worship it; it would not be idolatry, since it was made in the image of nothing that is in heaven above, or that is in earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.”6

Bushnell was taken aback, but he decided to try a white lie to win Ericsson a contract for the third ironclad. He returned to New York and told Ericsson that two of the three members of the board were favorable, but that Davis had some technical questions. Ericsson immediately agreed to go to Washington and answer the questions. In a bravura performance, he won them over, including Davis. They gave him a contract but specified that the ship must be built in ninety days and prove to be a “complete success” (without defining the criteria for success) or the builders must refund the $275,000 the government agreed to pay for it.

Ericsson got started at once. He subcontracted several parts of the vessel while maintaining close supervision of the building of the hull and turret. He named his ship the Monitor to signal its purpose to admonish and punish the South for its wrongdoing. A flat-bottomed hull housed all the machinery and was topped by a rotating turret protected with eight inches of plating and containing two 11-inch Dahlgren smoothbore guns that could fire a 170-pound shot or 136-pound shell in any direction except straight ahead, where the pilot house sheathed in nine inches of armor was located.

The novel features of the Monitor caused some observers—including naval traditionalists—to mock it as “Ericsson’s folly,” a cheesebox on a raft, or a tin can on a shingle. Admitting that “this vessel is an experiment,” the seventy-one-year-old chairman of the Ironclad Board, Commodore Joseph Smith, named forty-three-year-old Lieutenant John Worden to command it. “I believe you are the right sort of officer to put in command of her,” he told Worden. The crew were all volunteers. One of them wrote that “we heard every kind of derisive epithet applied to our vessel . . . an ‘iron coffin for her crew’ & we were styled fool hardy for daring to make the trip in her, & this too by naval men.”7

The Monitor’s almost-submerged hull presented a small target to enemy fire. But would it float with all that iron? Doubters were proved wrong when it came down the ways in Brooklyn on January 30, 1862, and floated with exactly the eleven-foot draft Ericsson had predicted. Two weeks later, the Virginia was launched in Norfolk, where she remained upright and buoyant with a twenty-two-foot draft when fully loaded with coal and ammunition. Mallory appointed Franklin Buchanan as her captain. “The Virginia is a novelty in naval construction, is untried, and her powers unknown,” he acknowledged to Buchanan; nevertheless, “the opportunity and the means of striking a blow for our Navy are now for the first time presented.”8

Both ships went into action after very little in the way of sea trials to work out the flaws and train the crews. On March 8 Buchanan took the Virginia down the Elizabeth River on what the crew thought was a trial run. Not until they emerged into Hampton Roads did he tell them that this was the real thing. Accompanied by two gunboat consorts, the Virginia headed toward Newport News, where two sailing frigates were anchored: the fifty-gun USS Congress and the twenty-four-gun USS Cumberland. Firing a broadside at the Congress as he passed, Buchanan steamed toward the Cumberland as the Virginia’s powerful 7-inch Brooke rifles riddled the helpless frigate, whose shots in return “struck and glanced off,” in the words of one Northern witness, “having no more effect than peas from a pop-gun.”9 Following up on Brooke’s experiments with tallow grease, Buchanan had the ship coated with it “to increase the tendency of the projectiles to glance.”10 The Virginia plowed straight into the starboard side of the Cumberland and sent her to the bottom. Virginia’s ram stuck in the Cumberland and almost took her down with the Union frigate until the ram broke off and freed the Confederate ironclad. The guns of the Cumberland kept firing until the water closed over them.

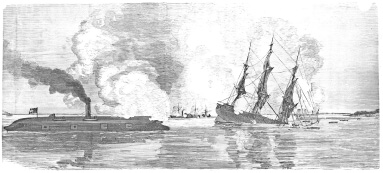

The CSS Virginia sinking the USS Cumberland, March 8, 1862. In the background are the Virginia’s two gunboat consorts, the CSS Yorktown and the CSS Jamestown, adding their firepower to the attack on the Cumberland. (From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated History of the Civil War)

The Virginia went next for the Congress, whose captain had grounded her to prevent the enemy from coming close enough to ram. But the ironclad’s guns did so much damage and killed so many of the crew that the Congress struck her colors. The commander of the Congress, Lieutenant Joseph Smith Jr., was the son and namesake of the chairman of the Ironclad Board. When Lieutenant Smith’s father learned that the Congress had surrendered, he said simply: “Then Joe is dead.” And indeed he was.11 As the Virginia’s consorts approached the Congress to take off the wounded, Union infantry on shore—who maintained that they had not surrendered—opened fire on them with small arms. Incensed, Buchanan recalled the boats and opened fire again on the Congress with hot shot and incendiary shells, setting her afire.

Meanwhile, the screw frigate USS Minnesota had steamed up from her anchorage off Fort Monroe to get into the fray. But she ran aground, and her 9-inch Dahlgrens seemed to make no more impression on the Virginia than had those of the Cumberland. Before the Virginia could attack the Minnesota, the falling tide compelled her to return home. But no one doubted that she would be back on the morrow. She left behind 121 dead on the Cumberland and 240 on the Congress, which blew up that night when the fire reached her magazine. It was the most lethal day in the history of the U.S. Navy until December 7, 1941.

The Virginia did not get off scot-free. Although none of the ninety-eight shots that struck her penetrated the armor, they did knock out two of her guns, shot away all of her deck fittings and part of her smokestack (reducing its draft), and killed two of the crew and wounded several others. One of the latter was Captain Buchanan, shot through the thigh when he came on deck in a fury carrying a musket to fire at Yankee infantry on shore who had refused to recognize the Congress’s surrender. The executive officer, Lieutenant Catesby ap R. Jones, took over and prepared to finish off the Minnesota and perhaps other ships the next day. But when Jones brought the Virginia out on the morning of March 9, he spotted a strange craft next to the Minnesota. “We thought at first it was a raft on which one of the Minnesota’s boilers was being taken to the shore for repairs,” wrote a midshipman on the Virginia. But the “boiler” ran out a gun and fired. The Monitor had arrived.12

It was not an easy trip, and she almost did not make it. On the second day out from New York, a storm came up and the waves washed over the decks, pouring down the blower pipes and stretching the belts that drove the ventilating fans so that they stopped working. Smoke and gases accumulated in the engine room and caused several firemen and engineers to pass out. The paymaster, William Keeler, who had some mechanical experience, helped pull out one of the unconscious engineers, “though by this time almost suffocated myself.” He then “succeeded finally in getting the ventilators started once more & the blowers going.”13

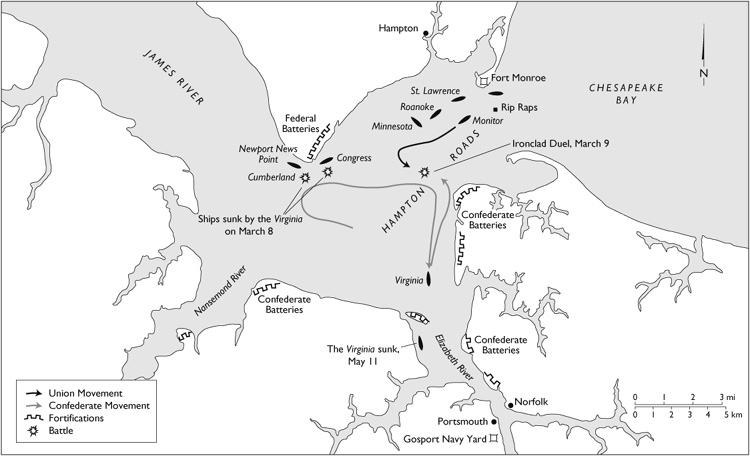

The Battles of Hampton Roads, March 8–9, 1862

The Monitor moved closer to the coastline where the water was smoother and finally made it to Hampton Roads after dark on March 8. There the crew learned of the momentous events of that day. They got a dramatic demonstration of those events just after midnight when the Congress blew up. Paymaster Keeler was on deck watching the burning frigate “when suddenly a volcano seemed to open instantaneously, almost beneath our feet & a vast column of flame & fire shot forth until it seemed to pierce the skies,” as he described the scene in a letter to his wife. “Pieces of burning timbers, exploding shells, huge fragments of the wreck, grenades & rockets filled the air and fell sparkling & hissing in all directions.”14

Because of their battle with the storm, none of the Monitor’s crewmen had gotten more than a few hour’s sleep in the past three days. Lieutenant Dana Greene, the Monitor’s twenty-two-year-old executive officer, had not slept for fifty-one hours when, as commander of the guns, he ordered the first shot fired at 8:30 A.M. But as the adrenalin started pumping, “we forgot all fatigue, hard work, and everything else,” he informed his family, “& went to work fighting as hard as men ever fought. We loaded and fired the guns as fast as we could—I pointed and fired the guns myself. . . . My men & myself were perfectly black with smoke, and powder.” The gunners “stripped themselves to their waists,” wrote Paymaster Keeler, “the perspiration falling from them like rain.”15 The same frantic action took place on the Virginia, while on the Minnesota a mile or so away from the action, the gunners also stripped to the waist to fire at the Virginia. At least two of their shots hit the Monitor instead as the two ironclads came to close quarters and sometimes fired their guns almost muzzle to muzzle.

Loading and firing those big guns took several minutes each on both vessels. During a battle of four hours, with several pauses, the Monitor fired only forty-one shots, scoring twenty hits, while the Virginia hit the Monitor twenty-three times out of an unrecorded number of shots. Nearly a hundred feet shorter in length and with only its turret and pilothouse more than one foot above the surface, the Monitor presented a fraction of the Virginia’s target area. Although the Monitor’s 170-pound shots cracked a few plates on the Virginia and the latter’s shells made dents in the Monitor’s turret, neither vessel seriously damaged the other. It could have been different. Expecting to attack the still-grounded Minnesota and other wooden ships on March 9, the Virginia carried only explosive shells in its magazine. They shattered and exploded when they hit the Monitor but did not have the penetrating power of a solid iron bolt or shot. The Monitor’s cartridges were charged with only fifteen pounds of powder each because there had been no time to test or “proof” the guns and their recoil inside the turret with heavier charges before they went into action. Later tests of the Monitor’s guns showed them capable of firing safely with forty-five pounds of powder. Even the thirty pounds normally used in 11-inch Dahlgrens probably would have done significant damage to the Virginia.

One of the Virginia’s shells did cause serious problems on the Monitor. It exploded against the pilothouse when Lieutenant Worden was peering through the slit and temporarily blinded him. Lieutenant Greene took over, but during the confusion after Worden’s wounding, the Monitor had moved away into shallower water. Thinking her disengaging, Lieutenant Jones decided to return to Norfolk with another victory to the Virginia’s credit. Watching the Virginia depart, the Monitor’s crew celebrated what they considered their victory. Immediately after returning to the north side of Hampton Roads, the chief engineer of the Monitor, Alban Stimers, wrote a note to Ericsson congratulating him on the “great success” of his invention. “Thousands have this day blessed you,” Stimers told him. “I have heard whole crews cheer you. Every man feels you have saved this place to the nation by furnishing us with the means to whip an ironclad frigate that was, until our arrival, having it all her own way with our most powerful vessels.”16

Stimers was hardly impartial, but even one of the senior lieutenants in the Confederate navy, George T. Sinclair, who watched the battle from the shore, wrote that the Virginia “met much more than a match in the Erickson [sic] from the fact that she is much faster, more easily managed, runs with either end first, and is invulnerable to any gun or guns I ever saw. . . . The Virginia is cut up a good deal, almost entirely by the Erickson, the projectiles from the other guns [i.e. of the Minnesota] having done her apparently little harm.”17

Whether the Virginia or Monitor won this particular showdown was less important, perhaps, than the symbolism of the battle as a victory of the future over the past. The graceful frigates and powerful line-of-battle ships with their towering masts and sturdy oak timbers would gradually fade into history and legend. March 9, 1862, witnessed a giant step in the revolution in naval warfare begun a generation earlier by the application of steam power to warships. Many contemporaries recognized as much, including the captain of the USS Minnesota, who had watched with growing astonishment as the little Monitor, with its two guns, saved his forty-gun frigate. “Gun after gun was fired by the Monitor,” he wrote in his official report, “which was returned with whole broadsides by the rebels with no more effect, apparently, than so many pebblestones thrown by a child . . . clearly establishing that wooden vessels cannot contend successfully with ironclad ones; for never before was anything like it dreamed of by the greatest enthusiast in maritime warfare.”18

One of the Confederacy’s foremost nautical scientists, Matthew Fontaine Maury, had previously advocated the construction of a fleet of small steam gunboats to swarm like bees to sting large Union warships to death. Several of these had been built or begun by early 1862. But the Virginia-Monitor clash pretty much ended that program. “As to the wooden gunboats we are building,” wrote Lieutenant Sinclair on March 11, “they are not worth a cent. The death knell of the wooden ships for war purposes was sounded last Saturday.” Maury himself ecstatically proclaimed that the Virginia “at a single dash, overturned the ‘wooden walls’ of Old England and rendered effete the navies of the world.”19

So dramatic was the impact of this event that both sides embarked on large-scale programs to build ironclads, most of them on the models of the Virginia and Monitor. In subsequent experience, however, these vessels turned out to have significant shortcomings. They were underpowered, slow, unseaworthy, and insufferably hot and humid in warm weather. The engines on Confederate ironclads were unreliable and prone to breakdowns; the rate of fire on Monitor-class vessels was agonizingly slow. But in the euphoric aftermath of the Battle of Hampton Roads, they seemed like war-changing superships.

As for the question of who “won” that battle, the tactical victory must be awarded to the Monitor. Its mission was to protect the wooden warships at Hampton Roads, and that mission it accomplished. But the Virginia won a strategic victory by infecting many Union naval officers with “ram fever” that inhibited their aggressiveness whenever Confederate ironclads were in the vicinity—or were suspected to be. That strategic impact began with the Virginia’s continuing presence at Norfolk, which neutralized much of the Union fleet and impeded its ability—or willingness—to provide naval support for General George B. McClellan’s efforts to capture Yorktown at the beginning of his ultimately unsuccessful Peninsula Campaign.

FLAG OFFICER Louis M. Goldsborough of the Union’s North Atlantic Blockading Squadron was in North Carolina waters with the gunboats supporting General Burnside’s campaign when the Monitor-Virginia battle took place. He hurried back to Hampton Roads and was greeted by an order from Secretary of the Navy Welles: “It is directed by the President that the Monitor be not too much exposed; that in no event should any attempt be made to proceed with her unattended to Norfolk,” where the Virginia was undergoing repairs.20

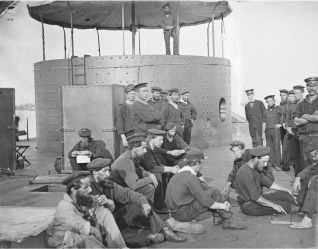

Part of the crew of the USS Monitor relaxing on deck after their fight with the Virginia (note the dents in the turret). (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

This constraint did not sit well with the Monitor’s crew, which wanted another chance at their antagonist. “If they would only let us go up the [Elizabeth] river & get at the rat in his hole it would suit us exactly,” wrote an officer on the Monitor. But “they fear to have us attack her for fear we may be used up” and then “the consequences would be terrible” by again exposing the fleet to the rampages of the Virginia, “so here we are compelled to remain inactive. . . . The fact is the Government is getting to regard the Monitor in pretty much the same light as an over careful house wife regards her ancient china set—too valuable to use . . . yet anxious that all shall know what she owns & that she can use it when the occasion demands.”21

The Union navy rushed several ships to Hampton Roads with reinforced iron-plated bows to ram the Virginia if she came out. One of them was the Vanderbilt, a gift to the government by the millionaire Cornelius Vanderbilt. This large sidewheeler was the fastest ship in the navy at the time. When the Virginia was repaired, she came down the Elizabeth River into Hampton Roads, but not far enough for the Vanderbilt to build up a full head of steam to ram her. Meanwhile, the Confederates devised a plan to lure the Monitor within reach of several small gunboats by feinting a foray by the Virginia. Men from the gunboats would then board and capture the Monitor. The latter refused the bait, however, causing newspapers in Norfolk to mock Yankee cowardice. Several crew members on the Monitor were stung by this charge. “All we want is a chance to . . . teach them who is Cowards,” they declared in a petition to their old commander, John Worden, who was still recovering from the wound to his eyes.22

This cat-and-mouse game between the two ironclads continued even after McClellan’s Army of the Potomac arrived in early April at the tip of the peninsula formed by the York and James Rivers. The navy had convoyed McClellan’s huge armada of troop transports down the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay without serious mishap, and the general counted on naval support to help him break the Confederate line across the peninsula anchored at Yorktown. Gustavus Fox urged Goldsborough to cooperate with McClellan, “bearing in mind that your first duty [is] to take care of the Merrimack. . . . At the same time I do not like to have the Army say that the Navy could not help them, so we are ordering everything we can raise to report to you.”23

Goldsborough told Commander John S. Missroon to proceed with three gunboats to assist McClellan’s attack on the batteries at Yorktown and Gloucester flanking the York River. Missroon took one look at the Confederate defenses there and reported that they had fifty big guns sited on the narrows in the river that could blow him out of the water. “All the gunboats of the Navy would fail to take it, but would be destroyed in the attempt,” he told McClellan. “To attack the works on the river front several heavy frigates or vessels of much endurance would be necessary.”24 McClellan complained to Fox and urged Missroon’s replacement by a more aggressive commander. “I fear friend Missroon is not the man for the place,” wrote McClellan. “He is a little too careful of his vessels, & has yet done us no good—not even annoyed the enemy.”25 Here was a classic example of the pot calling the kettle black. Just a few days earlier, McClellan had refused to attack the weak Confederate lines on the Warwick River despite overwhelming numerical superiority.

McClellan’s complaints brought orders from Welles instructing Goldsborough to “actively and earnestly cooperate” with the general. “It is important and absolutely essential” that the navy should give him “all the assistance he may require . . . consistently with your other duties.” The last phrase gave Goldsborough an out; his “other duties” included above all making sure the Virginia remained neutralized. “You know my position here,” Goldsborough reminded McClellan. “I dare not leave the Merrimack and consorts unguarded. Were she out of the way everything I have here should be at work in your behalf; but as things now stand you must not count upon my sending any more vessels.”26

Relations between McClellan and Missroon continued to deteriorate. On April 23 Missroon asked to be relieved then changed his mind and withdrew the request the same day. It was too late; a few days later, he was relieved and sent home, never again to hold an important command. Fox came down from Washington to check on the situation at Hampton Roads. When the Confederates evacuated their Yorktown line on May 3 just as McClellan was ready to open on them with his siege artillery, Fox inspected the batteries on the York River that had so intimidated Missroon. He claimed to find them much less formidable than reported. By this time in the war, Farragut’s fleet had passed Forts Jackson and St. Philip and two of Foote’s gunboats had run past Island No. 10—stronger works than those at Yorktown. “If Missroon had pushed by [at night] with a couple of gunboats,” Fox declared, “the Navy would have had the credit of driving the army of the rebels out, besides immortality to himself. . . . The water batteries on both sides were insignificant, and, according to all our naval conflicts thus far, could have been passed with impunity” and the batteries taken in reverse, because none of the guns pointed upstream.27

Fox was not the only high official who visited Hampton Roads and made observations that were critical of the navy’s operations there. None other than President Lincoln, along with Secretary of War Stanton and Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, came down in early May. Their purpose was to prod McClellan into action. But the general was at Williamsburg organizing the pursuit of retreating Confederates, so they prodded Goldsborough instead. At the president’s bidding, Goldsborough organized several gunboats and the Monitor to shell Confederate batteries at Sewell’s Point. In a spirited action, they drove the enemy away, causing Lincoln to wonder why Goldsborough had not done so earlier. The president also ordered General John Wool, commander of the Fort Monroe garrison, to land troops on the south side of Hampton Roads to take Norfolk. They accomplished this goal without opposition because the Confederates were evacuating the city after destroying the navy yard far more thoroughly than the Federals had done when they abandoned it a year earlier.

Although the Confederates would have abandoned Norfolk anyway after the main Southern army on the peninsula had retreated from the Yorktown line, the flurry of activity prompted by the president helped end two months of stalemate at Hampton Roads. Nothing was happening until Lincoln began “stirring up dry bones,” wrote an officer on the Monitor. “It is extremely fortunate that the President came down when he did—he seems to have infused new life into everything, even the superannuated old fogies [Goldsborough and Wool] began to show some signs of life.”28

Left behind when the Confederates evacuated Norfolk was the Virginia, whose draft was too great to get past shoals in the James River. On May 11 its crew blew her up to prevent capture. With the rebels apparently on the run, Commander John Rodgers of the new ironclad USS Galena led four other gunboats, including the Monitor, up the James River hoping to force the surrender of Richmond with their guns trained on its streets as Farragut had done at New Orleans three weeks earlier. Eight miles below the city, however, they encountered Fort Darling atop 200-foot-high Drewry’s Bluff on May 15. The ships could not run past the fort because the Confederates had driven pilings and sunk several cribs and hulks filled with stones at a narrow point in the river near the fort. The sailors would have to silence the fort’s guns before they could remove the obstructions. The Galena stopped 600 yards from the fort and opened fire. The Monitor came closer but discovered that it could not elevate its guns enough at that distance and had to fall back several hundred yards to where its smoothbore Dahlgrens were less effective. The Confederates concentrated the plunging fire of their seven guns on the Galena, hitting her forty-three times and perforating her three-and-a-half-inch armor both above and below the waterline. After five hours of fighting with seventeen killed and seven wounded on the Galena (some by sharpshooters concealed along the banks) and his ship holed like Swiss cheese, Rodgers gave up and dropped downriver with his flotilla. The Confederates in the fort suffered only seven killed and eight wounded. Paymaster William Keeler of the Monitor (which was hit only three times and had no casualties) went aboard the Galena and was appalled by the carnage. “Here was a body with the head, one arm & part of the breast torn off by a bursting shell,” he wrote to his wife, “another with the top of his head taken off the brains still steaming on the deck, partly across him lay one with both legs taken off at the hips & at a little distance another completely disemboweled.”29

Southerners were elated by their victory. Secretary of the Navy Mallory boasted two weeks later that the defenses at Drewry’s Bluff and at Chaffins’ Bluff across the river were now so strong “that I am afraid the enemy will not make a second attempt to pass them. I want him to try once more.” By July, Mallory could declare: “I have got the river so strongly protected now that I earnestly desire the whole Yankee fleet to attempt its passage.”30

They never did. According to Fox, President Lincoln “was very disappointed at the gunboats not being in Richmond.” From Goldsborough came a rejoinder that “without the Army the Navy can make no real headway towards Richmond. This is as clear as the sun at noonday to my mind.”31 But McClellan claimed that he could not spare the troops for a joint operation against Drewry’s Bluff. (A month later, Halleck told Farragut the same thing with respect to combined operations against Vicksburg.) Much of the Northern press, which had earlier praised the navy for its successes, now became critical of its failures. Sighing with exasperation, Gideon Welles lamented the public’s unrealistic expectations. “They tell us the Navy took New Orleans, why can it not take Richmond?” he wrote. “It overcame obstructions on the Mississippi, why can it not overcome them on the James River? Having done more than was expected, it is now expected we will do impossibilities.”32

Goldsborough was a prime target of criticism, much of it coming from within the navy itself. “The prevailing opinion among the ships on the [James] river,” wrote an officer on the Monitor, “is, that the old Commodore has a large fleet of vessels on his hands which . . . he don’t know what to do with.” Goldsborough “is not the man for the position he occupies. . . . He is coarse, rough, vulgar & profane in his speech, fawning and obsequious to his superiors, supercilious, tyrannical, & brutal to his inferiors.” Weighing 300 pounds, he was “a huge mass of inert matter & known throughout the whole fleet” as “Old Guts.”33

Welles shared many of these sentiments. On July 6 he created the James River Flotilla and gave command of it to Charles Wilkes (of Trent affair notoriety), who was instructed to report directly to the Navy Department instead of to Goldsborough. By this move, Welles divested Goldsborough of one-third of the ships in his North Atlantic Squadron. Complaining bitterly that this order “places me in a most humiliating attitude before the public and Navy,” Goldsborough asked to be relieved and transferred to an administrative position in Washington. Welles readily complied but tempered the implied rebuke by having Lincoln promote Goldsborough to rear admiral as he was put on the shelf for the rest of the war.34

Welles had no illusions about Wilkes, whom he privately described as “ambitious and self-willed . . . unpopular in the Navy . . . interposes his own authority to interrupt the execution of the orders of the Department.” But in the light of lingering public acclaim for Wilkes’s seizure of Mason and Slidell, Welles found it “almost a necessity that something should be done for Wilkes.” The James River Flotilla was the solution, which had the added benefit of easing out Goldsborough.35

To replace Goldsborough, Welles appointed Samuel Phillips Lee as the new commander of the North Atlantic Squadron with the rank of acting rear admiral. A native Virginian and a cousin of Robert E. Lee, he had never wavered in his loyalty to the United States. He had proved himself one of Farragut’s best fighting captains in the campaigns against New Orleans and Vicksburg. Lee was also well connected in Washington, where his wife, Elizabeth Blair Lee, was the daughter of the prominent politico Francis P. Blair and sister of Lincoln’s postmaster general, Montgomery Blair. During the next two years, Lee would earn more prize money from the capture of blockade-runners than any other squadron commander but also more criticism for the large number of runners into and out of Wilmington that his squadron did not catch.

One thing Lee did not have to worry about was Wilkes. By the time Lee took up his new command on September 2, Wilkes was gone and the separate James River Flotilla existed no more. After General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia drove the Army of the Potomac away from Richmond in the Seven Days Battles, Lincoln and his new general in chief, Henry W. Halleck, decided to withdraw the army from the peninsula. Both McClellan and Wilkes protested this decision, but by mid-August it was a fait accompli. The James River Flotilla performed its last duty in convoying the transports that evacuated the army and returned it to northern Virginia, where part of it fought at Second Bull Run. For the time being, the Confederates owned the James River again as they also owned the Mississippi from Helena down to Port Hudson.36

WELLES STILL HAD THE PROBLEM of what to do with Wilkes. At Lincoln’s and Secretary of State Seward’s behest, on September 8 Welles appointed the headstrong officer to command a “flying squadron” of seven warships to patrol the West Indies in search of Confederate commerce raiders and blockade-runners.37 American diplomats in Britain and its colonies had gathered intelligence about the “Oreto” and “No. 290,” ships that had been built in Liverpool as commerce raiders intended to destroy American merchant ships and whalers. Both vessels had evaded the British neutrality laws and gone to sea as the CSS Florida and CSS Alabama. Wilkes showed more zeal for trying to capture blockade-runners—which would earn him prize money—than for finding and fighting the Alabama, which began her depredations in September 1862. “It is desirable to break up the illicit traffic,” Welles told Wilkes, “but the first great and imperative duty of your command is the capture and destruction of the Alabama . . . and similar cruisers of a semi-piratical nature.”38

The launching of the Florida and Alabama in the summer of 1862 was another element in Confederate efforts to blunt and even reverse the momentum of Union naval success. The origins of this endeavor went back more than a year. At the same time that Naval Secretary Mallory sent James North to Europe to buy or build ironclads for the Confederacy, he also dispatched James D. Bulloch to England to buy or build ships suitable for destroying merchantmen.39 Bulloch was the right man for the job. A native of Georgia who was a veteran of fourteen years in the U.S. Navy and eight years in commercial shipping, he had the maritime knowledge, business contacts, and financial acumen to acquire suitable vessels and to navigate his way through the obstacles of doing so in a foreign nation that did not recognize the Confederacy. Although Bulloch wanted to command one of these ships himself, Mallory found him so valuable as a procuring agent that he kept him in Europe for the entire war.40

In the summer of 1861, Bulloch contracted with shipbuilding firms in Liverpool for the construction of two vessels that became the Florida and Alabama. Each was rigged as a sailing ship with a steam-driven propeller for added speed and maneuverability when chasing a prize. While cruising under sail alone, the propeller could be lifted into a well under the stern to reduce drag. Each ship carried eight guns to enable it to fight Union warships if necessary. As the vessels neared completion in the spring of 1862, their warlike purpose was an open secret in Liverpool, which was a center of pro-Confederate sentiment. The city had been “made by the slave trade,” observed an American diplomat tartly, “and the sons of those who acquired fortunes in the traffic, now instinctively side with the rebelling slave-drivers.”41 The construction of these ships was an obvious violation of British neutrality. The Foreign Enlistment Act prohibited the construction and arming of warships in Britain for a belligerent power. But Bulloch was a master of misdirection. The Confederate government itself was not a party to the contracts he had negotiated. The Oreto (Florida) was supposedly being built for a merchant of Palermo. The American consul in Liverpool, Thomas H. Dudley, amassed a great deal of evidence that the Oreto was intended for the Confederacy. Minister Charles Francis Adams presented this evidence to the Foreign Office.42 But the Oreto was allowed to go to sea in March 1862 as an ostensible merchant ship with a British crew and without any guns or other warlike equipment. In August she took on her armament, ammunition, and supplies that had been separately shipped to an uninhabited cay in the Bahamas.

Confederate navy Lieutenant John N. Maffitt christened the Oreto as the CSS Florida and took her to Havana to complete fitting out and fill up his crew. But several crewmen were sick with yellow fever, and others succumbed in Cuba. Maffitt decided to make a run for Mobile with a skeleton crew of eighteen men, some of whom, including Maffitt himself, were infected with the deadly fever. As the Florida approached the blockade fleet off Mobile in broad daylight, the executive officer wanted to wait until night to slip into the bay. No, said the feverish Maffitt. “We will hoist the English colors as a ‘ruse de guerre,’ and boldly stand for the commanding officer’s ship; the remembrance of the delicate Trent affair may perhaps cause some deliberation and care before the batteries are let loose on us; four minutes of hesitation on their part may save us.”43

The senior officer on the blockade was Commander George H. Preble, grandson of the famous Captain Edward Preble, who had won renown in wars against the Barbary states. From his flagship USS Oneida, Preble hailed the supposed British ship. When he got no response, he fired a shot across her bow. The Florida paid no attention. Mindful of orders not to alienate the British by firing on their ships, Preble sent two more shots across the bow to stop the silent vessel, which only sped up. Preble then ordered the Oneida to fire in earnest, scoring several hits and wounding half the crew. “The loud explosions, roar of shot and shell, crashing of spars and rigging,” wrote Maffitt, “mingled with the moans of our sick and wounded, instead of intimidating, only increased our determination to enter the destined harbor.” With her superior speed, the Florida finally made it to the protection of Fort Morgan and into Mobile Bay.44

Farragut was “very much pained” by this incident, and he reprimanded Preble for a serious error of judgment in not firing directly into the Florida after she failed to heed the first warning shot. In his defense, Preble cited the general orders not to antagonize Britain and noted that all of his officers assumed that the ship was British. The Navy Department knew that the Florida (which they still called Oreto) was in the Caribbean but had not gotten word to Preble. “Had I been officially or unofficially, in any way, informed that a [Confederate] man-of-war steamer was expected or on the ocean,” he wrote, “I would have known her true character and could have run her down.”45

Preble’s defense did him no good with Welles, who took the report to Lincoln with a recommendation that Preble should be cashiered. Welles had endured a torrent of criticism for deficiencies in the blockade and for the navy’s supposed failure to protect merchant ships from privateers and cruisers. He needed a scapegoat—or as he put it, an example to encourage greater vigilance—and Preble was it. “If that is your opinion,” Lincoln told Welles, “it is mine. I will do it.”46

Preble was a popular officer in the navy and carried a proud name. Pressure built almost immediately for his restoration to rank. Farragut was upset that his reprimand of Preble “should have drawn upon him such summary and severe punishment.” After reviewing all the evidence in the case, Lincoln decided—against Welles’s advice—to restore Preble to the navy at his rank of commander, but he spent the rest of the war relegated to marginal commands.47

The Florida would remain bottled up at Mobile for more than four months. Meanwhile, the Alabama began her career as the most notable—or notorious—commerce raider. James Bulloch had to perform even greater legal legerdemain to get her out of England than in the case of the Oreto. Consul Thomas Dudley matched Bulloch in a contest of spies, double agents, and lawyers to pile up evidence of No. 290’s warlike purpose and Confederate ownership. “The United States authorities in this country have used every possible means of inducing the British authorities to seize, or at least to forbid the sailing of, the Alabama,” wrote Bulloch from Liverpool.48 But his talents for obfuscation and Foreign Secretary Lord John Russell’s initial skepticism about the largely hearsay nature of the evidence of Confederate ownership that Dudley presented caused delays in British investigation of No. 290’s real purpose. By the time Russell became convinced that the case required a closer look, it was too late. Receiving word from a double agent that the British government was about to seize the ship, Bulloch took her out on July 29 for a “trial run” from which she never returned. Aware that the USS Tuscarora was lying in wait, No. 290 headed north around the tip of Ireland to avoid her, then south to the Azores for rendezvous with a British merchant ship carrying ordnance and supplies. On August 24, No. 290 was commissioned as the CSS Alabama with the redoubtable Raphael Semmes as captain and a mostly British crew.49

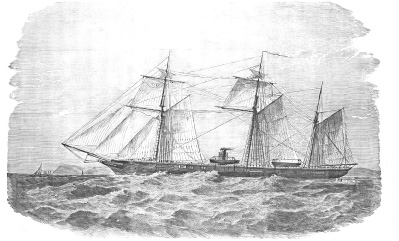

“No. 290” in British waters near Liverpool before she took on her guns and became the CSS Alabama. (From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated History of the Civil War)

During the next three weeks, the Alabama captured and burned ten American ships, eight of them whalers. Whale oil made a spectacular bonfire, wrote a midshipman from Georgia, “filling the wide Ocean with smoke and standing as still to her fate as though she were calling down curses on the head of Abe Lincoln and his Cabinet.”50 Gideon Welles did most of the cursing of “the connivance of British authorities” in allowing these “British wolves” to escape and prey on American commerce.51 An international tribunal eventually agreed with Welles and ruled that the British government must compensate American shipowners for the losses caused by the Crown’s negligence in failing to enforce its own neutrality laws.

But that happened ten years later. In 1862 Welles could only gnash his teeth about the Alabama’s continued destruction of merchant ships as Semmes moved away from the Azores into the North Atlantic. By November 30 the Alabama had burned twenty-one merchant ships or whalers, all of them sailing vessels that could not escape when the Alabama put on steam. Semmes used the same tactics he had perfected with the Sumter. He would fly the American flag or sometimes British or French colors as he approached a ship, then run up the Confederate flag after she hove to under the Alabama’s guns.

Orders went out from Washington to a dozen navy ships to drop everything else and go after the raider. Rumors and reports placed the Alabama here, there, and almost everywhere from Cape Verde to Nova Scotia to Bermuda to the Windward Islands to the coast of Brazil. The clamor against the navy for its failure to catch the raider caused even Sophie Du Pont, wife of Rear Admiral Samuel F. Du Pont, to join the chorus of criticism. The admiral tried to explain. “What vexes me,” he wrote, “is that so few people know or understand what a needle in a haystack business it is to chase a single ship on the wide ocean.”52

On one occasion, the USS San Jacinto spotted the Alabama in the harbor of Fort Royal at Martinique. Under international maritime law, belligerent warships must not fire on each other within three miles of a neutral shore. While the San Jacinto waited outside that limit, the Georgia midshipman on the Alabama described how the French officials “showed us every kindness imaginable, giving us charts of the harbor and inviting us up to their club rooms.”53 That night the slippery Semmes bribed a double agent to send up rockets in one direction to alert the San Jacinto while he escaped from the harbor on the opposite course.54

American shipowners and merchants began transferring registry of their vessels to neutral nations, principally Britain, or ownership of the cargoes to citizens of those nations. Since the Alabama could not take its prizes into port to determine ownership, Captain Semmes constituted himself the judge of a Confederate admiralty court on board ship. If a captain or supercargo could prove non-U.S. ownership of the cargo on an American ship, Semmes would bond the ship (require the captain to sign a bond for the estimated value to be paid to the Confederate government after the war) and let it go. Semmes followed this procedure with five of the twenty-six American ships he captured by the end of 1862. He required some of these ransomed vessels to take the prisoners that the Alabama had captured on ships she burned. In several other cases, however, he judged the papers showing foreign ownership of cargo or vessel to be fraudulent on technical grounds (such as not having a consul’s stamp). He then burned them without further ado, in some cases creating great resentment by neutrals that actually did own part of the cargo. Of course, Semmes had to let many of the ships he stopped go free because both vessel and cargo had legitimate papers showing neutral ownership. As time went on, more and more American ships legally transferred to foreign registry, beginning the “flight from the flag” that crippled the American merchant marine.55

The exploits of the Alabama, coupled with other Confederate initiatives on land and water from the summer of 1862 through the spring of 1863, ushered in a period of defeat and discouragement for the Union navy as well as for the Union cause in general. The ways in which the navy coped with these unfamiliar experiences would go far to shape the course of the war.